Coaching for Awareness-Based Systems Change

June 27, 2022Transformation,Blog,Network Leadership,TransformationLiberating Structues,leadership,Systems Change,Collaboration

In the fall of 2019, a few of the founders of the Illuminate network (including CoCreative, Garfield Foundation, McConnell Foundation, and Academy for Systems Change) collaboratively hosted a gathering of systems change “capacity-builders” who work as independent consultants or in small collectives as facilitators and advisors, from the US, Canada, Mexico, UK, EU, and First Nations. This was the first time these practitioners had been invited to meet together with peers to share their perspectives on the state of the field. The North American contingent of the group continued on through the upheavals of the pandemic, meeting virtually in 2020 and 2021 to explore themes of equity and integrating health and healing into systems change practice, as well as launching a pilot pairing senior and emerging practitioners to explore what systems-centric approach to leadership coaching might look like.

CLICK HERE to learn more about this unique systems coaching pilot or visit the Network Weaver resource page to download the full article.

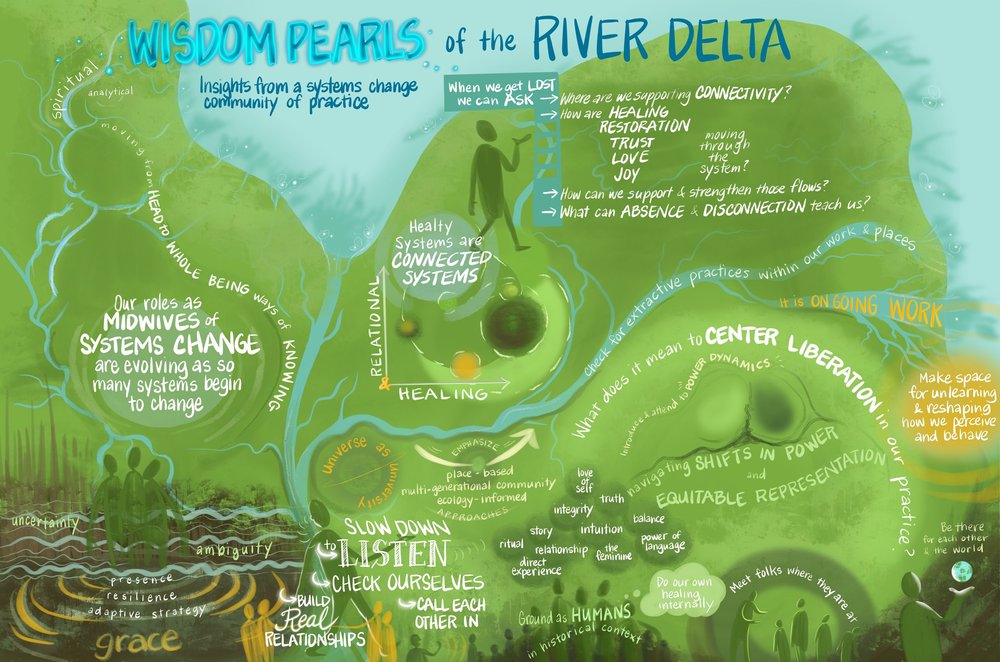

Check out the infographic below for some of the key insights from their COVID-era dialogues on the state of the field of systems change.

Learn more about the wisdom pearls HERE

You can also download a pdf with a link to this information to save to your personal library by visiting the Network Weaver Resource Page.

Katy Mamen is passionate about participatory change-making approaches that account for the complexity of multiple, interconnectedness crises and diverse lived experiences. She brings thoughtful and committed partnership to social sector clients advancing transformative systems change, drawing on expertise in social change strategy, facilitation and group process, systems theory, collaborative networks, and organizational development. In addition to process expertise, her work is informed by a strong background in economic justice, food & farming, water issues, and rural equity.

Brooking Gatewood helps leaders and groups clarify and enact the change they want in themselves, in their workplace, and in our shared world. At heart, her work is about co-liberation from systems of ‘power over’ and moving toward systems of ‘power with’ that honor individual agency as well as collective interests and wisdom. In practice, her coaching and consulting focuses on transformation across levels - from individual and team mindsets and behaviors to large-scale policy and systems change.

Originally published at IlluminateSystems.org

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

On Collective Liberation and Natural Networks: an Interview with LLC’s Nikki Dinh and Ericka Stallings

June 21, 2022Network Processes,Transformation,Blog,Transformation,Equity,Dismantle RacismLiberating Structues,equity,Systems Change,Collaboration,networks

I was able to meet with the Co-Executive Directors of the Learning Leadership Community, an organization I’ve long admired for their commitment to a community-focused transformative leadership practice. This past year, LLC was able to return to a co-Executive Director model which has freed up both Nikki Dinh and Ericka Stallings to focus on shifting LLC towards a more liberatory transformative leadership model. Part of this shift involves supporting the ongoing work of Network Weaver as it provides tools and resources to scale up access to weaver spaces and serve as a platform that amplifies the impact of BIPOC weavers and leadership practitioners on their communities. More deep-rooted shifts involve the difficult work of making even more room for thinking about and practicing liberatory frameworks that make equity work within this system sustainable for people who come from othering backgrounds.

“We look at leadership as a tool for transformation. To say that we are “equitable” within this current system, which is in and of itself inequitable is not necessarily our goal. Racial Equity being a path towards liberation, that's the change that we're trying to seek.”

– Ericka Stallings

In this interview, we talk a little bit about both Nikki and Ericka’s vision for LLC, liberatory processes, how community is the first network we come into, and why the work LLC is doing matters right now. Nikki and Ericka’s responses have been edited for clarity, but all effort has been made to maintain the integrity and spirit of their words.

* * *

Can you talk to us a bit about liberatory processes?

Nikki: “Liberatory” is a why, but it's also a how for me, because it's not a destination. It’s not like race equity, where you can measure your way to a certain point in the data and then it switches over to being more equitable for certain communities. Liberation, collective liberation, co-liberation, however you want to see it, is going to be a forever journey. We’ve seen what it does to our community members when non-profits focus only on getting the data or policy right—there’s a disconnect. And so how we do it really matters to people. Ericka and I always talk about what it takes to make a movement or network whole. How do we get to just work in just ways? It's not the technical titles like executive director and weaver, though we need those too, but what we know from our experiences is that we need everybody--we need somebody like Ericka’s mom who will nurture you, and we need an aunt who is always keeping an eye out for all the resources and trying to connect people to them. The “how” stems from a deep love for people. We’re trying to bring some of that back, some of that love and care for each other while we're doing this really difficult work.

What's one thing that that Network Weaver, or even LLC is doing differently, to transform the field of leadership?

Ericka: We are shifting towards a different lens that asks: what does a collective liberation look like? What does it mean when we free ourselves and each other? That’s one change. We are also getting clear about what these questions around equity, liberation and transformation mean in different contexts. LLC is mostly domestic, whereas Network Weaver is international and therefore has a broader reach. Networks are not just interesting tools, but they actually result in change. How can we explore what a change ecosystem looks like and the role leadership plays in that? How can really thinking about the needs of varying stakeholders, and not just being focused on terms and buzzwords that are exciting, help us capture all the work that goes into the change process? How do we support the leadership of all of those other folks who are in that ecosystem? Holding space for those questions and others is one way I think we’re committed to doing things differently.

What is your vision for Network Weaver?

Nikki: Network Weaver is a tool and resource. Ericka and I have this analogy about pollination. In areas where bees and butterflies and all the natural super pollinators are dying off, there are efforts to self-pollinate or find other ways to pollinate. And that's why Network Weaver is so valuable to me. It's like an artificial butterfly. It’s trying to help solve a crucial short-term problem until we can get that butterfly population back up. It’s a useful tool to scale when we need to scale, but how can we also pay attention to what makes bees and butterflies thrive in the natural habitats because the goal always is to have natural networks. Growing up in a refugee community, we had a large cultural network and within that so many alternate systems to meet the needs of the community. You need to borrow money? You need prescription pills? There were people doing that for each other! I envision us also zooming out to see and appreciate a natural network of weavers that continue to connect and build alongside the Network Weaver space.

What's your vision for LLC?

Ericka: Oh, we have lots of ideas and hopes and dreams for LLC! Something that I hope doesn't change is that LLC is very relational. LLC is very people-focused, we care about people. It’s also a space that welcomes joy. And that's something we want to grow into. A vision that I have for LLC is that it is a space where people who want to lead in liberatory ways, and folks who want to support leadership that is transformational and liberatory, can collaborate. We are a space of experimentation, innovation, and community. I hope as a consequence of our work, that there are stronger movements for justice.

One of the things that I appreciate about LLC is that we are eco-centric rather than egocentric, which is something that our founder, my predecessor, used to say frequently, and I really value not having to make sure everyone knows that “it's us.” It’s more important that the work happened, rather than the credit be attributed to us. That focus on the communal, the collective, the ecosystem is something that remains part of the vision that I have for LLC. Our work has not just been about products and deliverables, but liberatory processes, and that has made the work fulfilling and joyful.

What’s a commitment you made to yourself during the pandemic that you intend to keep?

Nikki: I have made a commitment to root for me. It’s still a journey. I am surrounded by people like my sisters, my partner and my children, my collaborator Ericka, who think I'm so great. And I want to take on some of that energy and be like, I'm going to do it for me. And that's what has really emboldened me to be like, alright, look, we're doing liberatory work, we're gonna go there, because, you know, I was a lawyer—I know you can’t undo that kind of systems thinking overnight. I’ve had to work on this and believe in valuing this. And I've also known, because of my upbringing, that we can do better. So rooting for me is rooting for all folx entrenched in systems, for us to be a bit freer.

Ericka: One, I mean I have one commitment that I've made that is unexpected. And it's a group of women that I have coffee with, like virtual check ins with weekly.. We've been doing it since the beginning of the pandemic. The funny thing is we were not intimate friends before. We started this gathering to have regular conversations with agendas and learning goals and things like that, and they evolved or de-volved, depending on how you think about it, into very, very rich, deep emotional connections. I'm very proud and happy that I've continued to commit to these weekly check ins and also to those relationships.

Is there anything that you're like most excited for this year?

Nikki: We're doing some longer-term strategy work. In the next three to five years we will go bold with liberatory programming. Our lens for Network Weaver, for example, will be situated under the liberatory program side of the house. Everything we do will have to bring a kind of outside-the-system thinking which includes bringing in the perspectives and interests of people who are typically excluded from our systems. That said, I'm really excited to work with more people who are from other backgrounds, like refugees and trans folks, and queer folks, and people with disabilities. I have learned so much from people outside of our systems that I'm really excited for others to get that wisdom too.

Why LLC? Why Donate Now?

Ericka: One of my favorite quotes is: “if you give me a fish, you have fed me for a day. If you teach me to fish, you have fed me until the river is contaminated or the shoreline seized for development. But if you teach me to organize, then whatever the challenge, I can join together with my peers and we will fashion our own solution.”

With that in my mind, my hopes for the ongoing work of LLC and Network Weaver are in that vein; of prioritizing the people who are addressing issues in their communities and how folks in this space are supporting them. I'm hoping that the blog series we hope to launch soon will address how people are affirmatively and explicitly stepping back so that the people directly impacted come to the forefront. And I'm hoping these stories about the material, communal, and spiritual transformation that's happening help us see the real impact people are having on the communities they care about.

donate in the box above or click here

Ericka Stallings is the Co-Executive Director of the Leadership Learning Community (LLC) a learning network of people who run, fund and study leadership development. LLC challenges traditional thinking about leadership and supports the development of models that are more inclusive, networked and collective. Prior to LLC, Ericka was the Deputy Director for Capacity Building and Strategic Initiatives at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD), supporting organizing and advocacy and leading ANHD’s community organizing capacity building work. Ericka also directed ANHD’s Center for Community Leadership (CCL) which provides comprehensive support for neighborhood-based organizing in New York City. At ANHD she formerly directed the Initiative for Neighborhood and Citywide Organizing (INCO), a program designed to strengthen community organizing in the local neighborhoods. Before working at ANHD she served as the Housing Advocacy Coordinator at the New York Immigration Coalition (NYIC), managing its Immigrant Housing Collaborative. In addition, Ericka co-coordinated the NYIC’s Immigrant Advocacy Fellowship Program, an initiative for emerging leaders in immigrant communities. She received her undergraduate degree from Smith College, studied International and Intercultural Communications at the University of Denver and Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University.

Nikki Dinh is the daughter of boat people refugees who instilled in her the importance of being in community. Though she grew up in a California county that was founded by the KKK, her family’s home was in an immigrant enclave. Her neighborhood taught her about resistance, resilience, joy and love.

Her lived experiences led her to a career in social justice and advocacy. As a legal aid attorney, she learned from and represented families in cases involving immigration, domestic violence, human trafficking, and elder abuse. Later, she joined the philanthropic sector where she learned from and invested in local leaders, networks and organizations throughout California. At Leadership Learning Community, she is excited that her work will continue to be guided by the belief that the people in communities we seek to serve are best positioned to identify and create solutions for their community.

About the Author

Sadia Hassan is a writer, organizational consultant and network weaver who enjoys using a human-centered approach to think through inclusive, equitable, and participatory processes for capacity building. She is especially adept at facilitating conversations around race, power, and sexual violence using storytelling practice as a means of community engagement and strategy building. She has received a Masters in Fine Arts, Poetry at the University of Mississippi and a Bachelor of Arts in African/African-American Studies from Dartmouth College. You can read more of her work at Longreads, American Academy of Poets, and The Boston Review. https://sadiahassan.com

feature photo by Lee 琴 on Unsplash

Networks: Resourcing Relationships and Interdependence for an Equitable Future Now

June 14, 2022Systems Change,Network Weaving,The Big PictureTransformation,Blog,Transformation,Dismantle Racism,equity

Networks for Equity and Systems Change

The events of the past year have made clear what many in and outside of philanthropy already knew: that equality in resource distribution is not equity, that much of what was thought impossible to change – telework policies, reporting requirements, fiduciary responsibilities – is suddenly possible, that what we need to shift big systems is interdependence (not codependence), and that what is needed for this shift to happen begins with strengthening our relationships with one another – as individuals, organizations, and communities.

Networks offer a structure for linking people and groups of people with a shared vision and shared values to build and strengthen the relationships necessary to shift big systems. By offering us opportunities to work together in ways that challenge us to build different understandings of and relationships to power and to each other, we are able to move in more interdependent and interconnected ways.

Many individuals and organizations – particularly those rooted in Black and Native communities, queer communities, and immigrant communities – have experience working in networks both rooted in and working to advance equity and justice yet are often not sufficiently resourced for this work. Other entities, including many funders, are bringing increased attention and resources to working in this way and yet these many groups that are poised to resource networks are still just learning about how to do so in ways that align with equity and manage disproportionate power dynamics.

In this moment of possibility for reimaging big systems to live our imagined future of love, dignity, and justice now, we are sharing some learning from a late-2019 gathering of nearly 70 network funders, practitioners, and participants about how network practitioners and some funders are nourishing and growing networks for equity and systems change.

An Experiential and Embodied Approach to Learning in Networks

The Networks for Equitable Systems Change gathering was co-created in partnership with Change Elemental, Uma Viswanathan and Matt Pierce at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and a design team of network practitioners including Allen Kwabena Frimpong, Aisha Shillingford, Marissa Tirona, Robin Katcher, and Deborah Meehan. The group came together to engage with practices for building, resourcing, and sustaining networks. Together, we set out to learn about the following questions:

- How have funders and other organizations worked together in networks that promote equity and systems change?

- What are the barriers to resourcing networks for equitable systems change and what would it take to shift those barriers?

- What is the personal work and way of being needed to fully engage in networks, equity and systems change?

While desk research and interviews can be useful learning tools, we decided to take an experiential and embodied approach to learning about our questions. By bringing convening participants into the experience of network building in real time, we were able to create shared experiences that led to shared understanding about what it takes to build and sustain networks that can shift systems.

We can’t shift systems when we’re only touching one part of the elephant. We need spaces where the whole ecosystem comes together, bringing various perspectives that can give us a picture of the whole. Rather than host separate conversations with funders, intermediaries, and grassroots organizations, the gathering brought together many parts of network ecosystems to discuss how folks were experiencing power sharing within networks.

Below are some of the ways the experiential design of the convening – in addition to the deep expertise and knowledge that participants brought to bear – helped co-create our elephant and answer some initial questions about networks…

We Challenged Dominant Ways of Building Alignment through Rigid Frameworks and Definitions and Instead Reached Shared Understanding with Storytelling

Through experiential learning and storytelling, convening participants aligned on shared definitions for what we mean by a network as well as successful practices for building, sustaining, and resourcing networks.

With our design team, we co-created a learning network that engaged people with different access to resources, different kinds of power, and different experiences and roles in networks. We were concerned about bringing so many different folks together to talk about networks when we all were coming in with these different experiences, definitions, etc. We faced the same pressure points that networks face: how do we distribute resources across this group and compensate people for their time and labor? How can we facilitate more open discussions with transparency and deeper sharing among groups who have different priorities, expertise in networks, roles in the movement ecosystem, and kinds of power? Where do we need alignment and shared definitions and where should we hold generative tensions and conflict?

Initially, we considered aligning the group through some shared definitions and research in networks before coming together, but that process seemed time consuming and didn’t fully honor the wisdom in participants’ different perspectives and experiences. Instead of creating written definitions and a compilation of research to align participants on a common framework, we had attendees prepare spark stories – a short story that communicated their experiences and challenges in a network when working across funders, individuals, grassroots organizations, and other entities. Participants shared stories in small groups and each group created an image to show similarities and differences in themes across stories. The storytelling accelerated shared understanding in small groups and highlighted the multiple perspectives in how participants understand and experience networks.

Many participants also shared their spark stories in video conversations. In this video, design team member Allen Kwabena Frimpong and Rachel O’Leary Carmona from AdAstra Consulting share their own definition of a network.

We Used Art Making to Illuminate Power Differences and Start Deeper Conversations about Power Sharing in Networks

Navigating power differentials – including naming and managing them – was a key element in supporting shared learning in this diverse space and also mirrored the ways in which engaging with power can create generative conflict that supports network building or exacerbates unnamed tensions that derail it.

At one point before the convening, some funders were feeling nervous about their power relative to other groups and considered having a separate space. We ultimately decided against that and instead brought funders together to discuss how we might acknowledge and visibilize power differentials (rather than obscure them). We also saw this as a way for funders to build practices for being in spaces where they have more power related to resourcing (such as in a network).

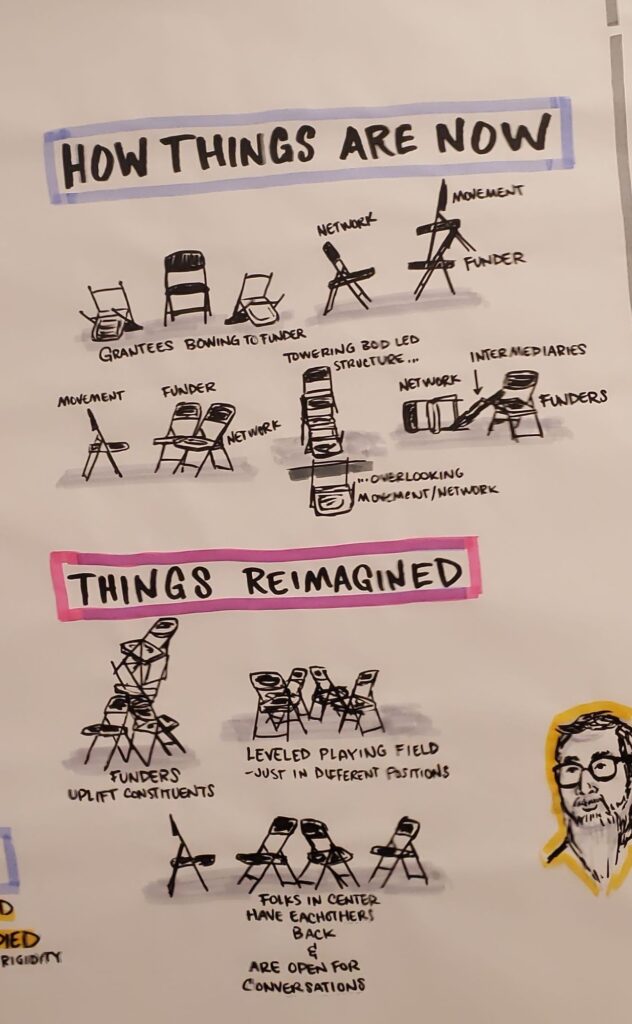

In an exercise from Theater of the Oppressed participants could make visible the power differences between funders that financially resource networks and other network participants. Participants positioned chairs differently based on their vantage point and each new sculpture was in dialogue with the previous one, creating space for different perspectives in support and in tension with each other.

In this spark story, Sage Crump, Cultural Strategist, shares her experience with power as an intermediary navigating the relationships between networked organizations and funders.

Starting with this creative exercise created a bridge to harder conversations about the barriers to equity in resourcing networks such as how money is distributed across network participants, inappropriate use of power, or challenges that come up when there is misalignment between the equity values of a network and the culture of a funding institution.

Convening participants Eugenia Lee of Solidaire and Rajiv Khanna from Thousand Currents discuss what it takes for people inside large funding institutions to align foundation culture with equity and other values needed to better support networks.

We Made Space for New Conversations about Resource Sharing and New Processes for Resource Distribution

Equity should inform how we resource people to be and learn together across power, identity, and roles and then to do together (in networks). Yet external systems, norms, and habits can often inhibit us from living out our values. One example of this is the radical redistribution of resources in neworks, which requires leaning into new practices for how we work together and support each other given our proximity to power and resources.

To financially support people’s attendance at the gathering and their contributions to the space, we created an equity fund. The set-up and distribution of the convening’s equity fund provided the group with an opportunity to lean into these new ways of being. It required vulnerability from participants in asking for what we need and for those holding financial systems to figure out creative ways of reducing the administrative burden on participants, for example by offering stipends rather than reimbursing receipts.

To guide us in these new (to some) ways of being and doing, we created a set of fund principles. Adapted from Leadership Learning Community, the principles included:

- People can ask for what they want and need

- Adopt an abundance mindset (we can always find a way to get more)

- Function with trust, no questions asked

- Give people examples of what they might use funds for (e.g., lodging, childcare, funds to cover a missed day of work for hourly professionals, etc.)

At first, people asked for very little. After more enthusiastic nudges and encouragement to lean into the principles and the discomfort of asking (for example, by looping back to confirm, clarifying our equity principles, and sharing more examples of what people have asked for) more participants felt comfortable asking for what was truly needed.

The initial hesitancy from participants prompted us to think more about who feels entitled to ask for equity funds and how that may relate to our individual sense of worth (eg. how much do I really need this?) and relationship to the collective (e.g., how much might others need relative to me?).

During the convening, we shared what we learned from managing our equity fund in this meme-filled presentation, including how we pushed for a “no receipts” policy, which was challenging to navigate from a compliance perspective but saved a great deal of administrative time.

In this spark story, convening participants Elissa Sloan Perry from Change Elemental and Alexis Flanagan from the Resonance Network share another example of resource distribution within a network, including the vulnerability and trust needed to talk openly about personal wealth as a way towards more equitable resource distribution.

While some of the experiential learnings from the convening are captured above, network practitioners and funders also brought together learnings from past experiences in leading with equity and navigating power differentials within networks including how funders operate in networks; the different forms and shapes networks might take; capacity, impact, and infrastructure needs in networks; and ways of being needed to build, resource, and support networks.

To dig into more stories and insights as well as many other resources about networks, see the report, “Resourcing Networks for Equitable Systems Change: Perspectives from Funders, Intermediaries, Individuals and Organizations on How We Fund and Support Networks for Equity.”

Natalie Bamdad (she/her/hers), joined Change Elemental in 2017. She is a queer and first-gen Arab-Iranian Jew, whose people are from Basra and Tehran. She is a DC-based facilitator and rabble-rouser working to strengthen leadership, organizations, and movement networks working towards racial equity and liberation of people and planet.

Alison Lin (she/her/hers) supports leaders in authentic collaborations to transform people and systems toward love, dignity, and justice. With over 20 years of leadership experience, she draws from work in race equity, complex systems change, organizational development, learning through experimentation and life with a focus on issues affecting LGBTQ and BIPOC communities. She joined Change Elemental in 2017.

Video recording, editing, and photos by Breathe Media Group

Graphic recordings by Brandon Black

Cover photo by Brian Stout

Originally published at Change Elemental

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Inside philanthropy and networks

June 8, 2022Network Structure and Governance,Network Processes,Transformation,BlogTransformation,Systems Change,philanthropy

Collective Mind hosts regular Community Conversations with our global learning community. These sessions create space for network professionals to connect, share experiences, and cultivate solutions to common problems experienced by networks.

In July 2021, Collective Mind hosted a unique Community Conversation panel discussion about philanthropy and networks. The session featured experts who work across the philanthropic space and have deep experience with networks ranging from global and national to hyper-local levels and across the gambit of social causes. The panel included Heather Hamilton, Executive Director of the Elevate Children Funders Group; Hilesh Patel, Leadership Investment Program Officer of the Field Foundation; and Katie Davies, Manager of Strategic Networks Initiatives with Ignite Philanthropy.

Together, the panelists explored the most urgent topics on their minds as funders and funder organizers for social impact, and talked about the trends they’re observing within philanthropy as it evolves toward more progressive causes and systems-change work. The panel helped elucidate some of the mysteries behind philanthropic decision-making and strategy, and sparked conversation among participants about how networks can reimagine their approach to and relationships with donors.

Highlights from the conversation

Understanding the decision-making structures of philanthropies helps network practitioners see their work through a donor’s lens and ask themselves the questions donors need to have answered. According to the panel, grant seekers commonly overlook the disconnect between program officers (POs) and where high-level funding decisions are made. POs are engaged on the ground, hearing directly from leaders and impacted communities, and have a current view of how the field is evolving to help advise on strategy. But ultimately, the Board of Directors controls the purse strings and sets the strategic agenda, with POsimplementing their decisions. Boards often prioritize questions of financial risk when making strategy and investment decisions, as well as the potential for fiscal return or reward. Among the range of types of foundations, POs will also have different levels of autonomy and instruction and at times won’t have a lot of flexibility in what they can fund. For networks, this can be particularly challenging as the work and value of networks can be amorphous and long-term, presenting more perceived risk from a business point of view.

Furthermore, networks may not necessarily fall into the framework of how traditional Boards think of how change happens. By design, networks work collectively toward a goal or contribute to a solution, rather than being able to specifically claim impact as their own, which makes their value proposition less straightforward and tangible than programmatic outputs and numbers. To demonstrate impact for donors and stakeholders, groups will sometimes overclaim and attribute wins to their own efforts, which misrepresents the work and can undermine the notion of a shared purpose. This can muddle the message of how collective impact happens and its value. It is therefore both on networks to be thoughtful, effective storytellers and have strong mission clarity, and on donors to educate and challenge themselves on their conceptions of the role and value of networks to affect systems change and foster an enabling environment where change happens.

Effective philanthropy requires more and better Board education. At its roots, philanthropy assumes a binary between those doing work on the ground and seeking funds and support, and those with resources who make big decisions on behalf of social change work but have limited practical knowledge or experience of it. This dynamic is challenging to navigate and also problematic. More and more, POs are working to educate Boards, which are often composed of wealthy individuals, about social change and to create change within foundations on the inside. There is emerging interest in the philanthropic space to learn from and with communities of change and to become more responsive and accountable across leadership and decision-making. Networks can help POs in their efforts to push and educate leaders within foundations to understand more about movements, collectives, and networks, and how donors can be more effective partners for change.

One way this can be done is through measurement methods that are more true to life and the work of social change. Donors often miss that funding networks means that progress won’t always be linear or explicit. Not only can fixed metrics and reporting requirements put a burden on grantees and have undue influence on the work, but limiting impact work to spreadsheets and formulaic processes can drive artificial outcomes and stifle the chance to glean real learning and value. For some foundations, there’s a new effort to pivot traditional reporting requirements and formats to be more flexible, conversational, and focused on multi-directional learning. These processes reframe accountability to center what grantees and donors can learn from each other about how the field is evolving, what role they all play, and what progress is being made. Doing the work to understand why networks and coalitions are important leads to understanding the nature of networks and systems change.

Donors are also starting to embrace how the image and dynamics of leadership are shifting through the work of networks and movements. Whereas traditional leadership is marked by an individual with certain, often normative characteristics and the vision and actions they represent, networks and movements center the leadership of groups and shared efforts. In networks, there is often no one leader: leaders are pulled from different sections to be part of broader work, and the model and mission doesn’t prioritize individuals as leaders. These challenges to traditional notions of what leadership looks like both mirrors and goes beyond how the face of leadership is already changing generationally. Understanding networks for how they upend traditional leadership is another way to educate philanthropic Boards about collective action and collaborative leadership.

Miss the session? View the recording here.

Thanks again to our amazing panelists!

Emily is a seasoned nonprofit and social impact expert with 14 years of experience leading social justice organizations and programs from community to global levels. She specializes in program innovation and design, strategy and leadership, facilitation, and peer learning. Among Emily’s career highlights, she has served as Executive Director of a grassroots women’s rights and anti-violence organization in British Columbia, Canada; spearheaded global peer exchange networks and innovative women’s leadership programming; and designed cutting-edge participatory research about GBV in remote and Native communities.

Originally published at Collective Mind

Featured image found here

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

Building Trust Through Grantee Feedback

A Conversation with Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

In CEP’s recent publication, New Attitudes, Old Practices: The Provision of Multiyear General Operating Support, nearly all interviewed foundation leaders emphasized the importance of trust between funders and grantees. Moreover, CEP found that foundation leaders who provide more multiyear general operating support made an intentional choice to do so based on their belief that it will build trust, strengthen relationships, and increase impact.

When Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies (RNP), a foundation located in Bangalore, India, gathered feedback from its grantees through the Grantee Perception Report (GPR) in 2020, RNP was rated in the top 1 percent of CEP’s overall comparative dataset for perceptions of trust. Simultaneously, RNP grantees rated in the bottom 1 percent of the dataset for the amount of pressure they felt to modify their organization’s priorities in order to receive funding from the foundation.

How did RNP achieve this? To what practices does the foundation’s team adhere to build trust with grantees in their interactions? How do they think about trust-based philanthropy?

For answers to these questions, we recently talked to members of RNP’s leadership team: Founder-Chairperson Rohini Nilekani (who, with her husband Nandan Nilekani, has signed the Giving Pledge), Director of Strategy Gautam John, and Associate Director Natasha Joshi.

The team explains their approach in this new video:

Here are some more thoughts from Nilekani, John, and Joshi on several key elements of centering trust in their approach:

Starting with Trust is Important

Rohini Nilekani (RN): We’ve all been on the other side (of the funding table) and know how hard it is. Things change so quickly on the ground. We need to be agile and can’t be stuck with budget lines or line items that we have to stick to. Of course, you have to do due diligence, but if you don’t start off assuming the right intent and methodology on the other side, then what are you going to do? Then you must take over and do it yourself. When you’ve found the right leaders and institutions, you have to let them do what they believe in. Because passion and commitment are what drive this sector.

Just like you can’t tell Picasso to use a little less red or blue when you commission a painting from him, you can’t tell civil society organizations, “Okay fine, but just do it my way a little more.” It won’t work! Starting with trust, after basic due diligence, seems to me not just a moral but also a strategic imperative. We have to first try trust — always.

Gautam John (GJ): I’ve spent 10 years working as a grantee trying to raise money from foundations. And in my experience, you can’t co-create by saying, “Do it my way.” That’s not co-creation, that’s called convincing. Our goal is to create something together. Co-creation is difficult because it means letting go of some degree of control — and that’s hard to do.

The Need for Humility

RN: If you keep chasing attribution, you become your own chokepoint. In philanthropy, it’s more important to recognize contribution, rather than seeking attribution. I can’t see how you can achieve the philanthropic goal behind what you want to achieve by chasing attribution. You have to hold your goal close to heart and be willing to trust others. Nobody can go at it alone.

Honestly, none of us know how change really happens. We only have some theories about it. I try to walk back from too much certainty; to occupy the grey and occupy doubt; to think, “My ideas may not be right”; to not allow myself to say, “I am right”; to keep a mirror in front of myself. Yes, there may be occasions where your perspectives may be understood and absorbed. But if you insist on doing things your way, you’ll only get a service provider, not a partner. You’ll end up with a contractor or vendor relationship, rather than with a partner who you can walk with.

GJ: Philanthropists usually wake up in the morning saying, “We know all the answers,” when really, we should be waking up with questions. Because the idea of co-creation comes from being willing to let go of some amount of control and to act from a place of humility and curiosity. Humility is rare in the philanthropic sector. “We don’t always know — you do, and we might be able to learn something from you” is what we need more of.

More Long-term, Flexible, Unrestricted Funding

Natasha Joshi (NJ): Rohini Nilekani deliberately chose not to set up a registered foundation. We were afraid of creating too much bureaucracy because sometimes, too much bureaucracy can make it hard to be flexible and responsive in your giving.

GJ: High-quality civil society organizations deliver high-quality outcomes. You can’t have one without the other, so one needs to be willing to invest in their organizations, their people, and attract talent.

Strangely, many philanthropists don’t behave with their nonprofit partners the way they do in their businesses. How people see for-profit companies versus nonprofits can be very different; the very same person can have completely different views on how capital should be used. I legitimately struggle with this and I don’t know where it comes from. In India, perhaps, it’s because the idea of ‘service’ has a long and deep history. On the other hand, I hear philanthropists bemoaning the lack of talent in the civil society sector. But you can’t have it all without being willing to invest in organization building by committing to long-term, unrestricted funding.

RN: Some philanthropists are nervous about trusting civil society organizations. In India, at the onset of Independence, and 60 years later still, many civil society organizations were Marxist and left leaning. Businessmen, who are usually philanthropists because they are the ones with access to capital, are usually more market leaning. This creates a political ideology divide. As a result, philanthropists in India don’t even get into trust modus. Rather, they create their own independent implementation arms. This means that you don’t have to trust anybody. The question of trust can be bypassed because you can do it all by yourself.

Of course, when trust is broken, you can pull back and create more rules. There are things that we can do. But when you have a car accident, it also doesn’t mean you never get in the car again.

But like I said, in order for real social change to happen, nobody can go at it alone. One has to always try trust first.

About the author:

Charlotte Brugman is manager, assessment and advisory services, at CEP. If you’d like to learn more about understanding and improving your relationships with grantees, including through collecting grantee feedback via the Grantee Perception Report (GPR), contact Charlotte, who is based in Amsterdam and leads CEP’s work with global funders, at charlotteb[at]cep.org.

originally published at CEP.org

featured image found HERE

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

Reclaiming Choice and Agency in a Networked World

May 24, 2022Transformation,Blog,TransformationLiberating Structues,Systems Change,Self Organizing

Welcome! We are happy you chose to open this blog post! In this article we will explore:

- The difference between choice and decision; and why awareness of choice matters - as a (fundamental) way to engage with life.

- Different levels of networks & systems and how to navigate the levels with agency.

- How to choose with your whole being - as a means to align your deeper values and actions.

- Exercises and prompts to practice choice as a capacity.

We believe that it can be of use to change agents, social innovators, system entrepreneurs, and curious minds. Most importantly: We invite you to choose to fully engage with the article and share your reflections with us. We have laid out some opportunities to do so on the way :)

So let’s dive right in!

Choosing to Decide

Each day we make numerous decisions, from what we consume, such as food and media, to how we respond to others and to our environments, and beneath all of these decisions are choices. Yet, what is the difference between a choice and a decision? A decision often implies reaching a conclusion you can act upon, in this process something is determined. While a choice implies an act of choosing between two or more possibilities. In this way, ‘choosing’ is a practice of continually aligning toward various decisions. If we zoom out we may see that choices are how we navigate through life and how we arrive at decisions. Let’s take a moment to ponder this.

What was the most important decision you made today?

And what was the underlying choice you made that led you to that decision?

Choosing and deciding are related processes, yes, but they are fundamentally different in their nature. Choosing is relational, it is a process of orienting ourselves towards something of importance, such as our personal values, and what we hold dear. Choices lay out possible paths and open up fields of opportunities. While, deciding is directional; decisions are the concrete steps we take on that path.

If we shift from considering the individual level of choice to the collective level, we can see that human actions are a dominant driving force for what’s happening, and going to happen, on this planet. From this perspective our actions may look insignificant at a larger scale.

But an easily overlooked perspective is that we are not passive consumers or bystanders in the course of history. There is choice and agency everywhere, in the seemingly small moments of our daily lives, in the conversations we have with loved ones, or in choosing, or changing, our careers. Each moment holds an underlying choice we can engage if we choose to.

Now, a common argument is that the challenges we are facing are so grand and complex - that it doesn’t really matter what I intend, do or think.

In this article we will flip this argument around: In a networked world, there is nothing that matters more than what you do. Not only for you and your immediate environment, but also for the world at large. What you do, in turn, is deeply embedded in the choices you make, as your choices shape your orientation toward life.

Engaging with choice can also foster your sense of agency. Agency refers to the ability to direct your own actions in a meaningful way. In the field of systems impact, agency is often the precursor to creating change within our immediate environment or the larger social context we exist within and care about. As we reclaim our sense of choice, we inhabit more of our agency, which in turn enables us to have a greater impact.

Before we unpack this more and dive deeper into the exploration on how to reclaim choice and agency, we invite you to do a little exercise with us, to connect with what supports your sense of choice and agency.

You can follow the steps below or use this mentimeter survey for guidance: https://www.menti.com/txm61jx7f7

(if you use the survey, we will anonymously keep track of the responses - and you can also read through the results of others for inspiration)

- Think of a current situation that frustrates you - where you feel you don’t have choice or agency. This can be something in your immediate environment - or a larger social issue. How would you describe that situation? What emotions are present for you? What is the root cause of your frustration?

- Now, think of a moment in the past where you felt similar, but then experienced some sort of breakthrough - a moment where new opportunities emerged. Enter that moment now. Take a few deep breaths and observe what shows up for you - in terms of images, emotions or intuitions.

- Now consider, what made that breakthrough, that shift, possible? Note down a few words, lines or images.

We will return to this exercise at a later stage in this article.

Agency in a Networked World

We all exist in webs of relationships, which are the most basic form of networks. Networks exist within and around us. In nature we see networks of mycelium, mushrooms and fungi; the internet is a network of networks consisting of computers, routers and webpages. If we consider our bodies we can see that even our brain is made up of neural networks and synapses. Networks show us that it is important to focus on the individual elements as well as the relationships between them.

In essence, referring to our world as “networked” mainly means four things:

(1) We are part of more networks than ever before. Just count the number of initiatives, groups and organisations you are connected to - and compare it to the generation before you.

(2) the networks we are part of are larger in scope than they have ever been. Technology, mainly the internet, has made it possible to decouple social connections from physical proximity, at least to a certain degree.

(3) The networks themselves are connected. what happens within one network impacts others, for example a traffic jam or delayed trains in a transport system can lead to people being late to work.

(4) The networks we are part of, or deliberately not part of, shape our identity and actions. In turn, we also shape the identity and possible actions of these networks, yet usually to a lesser degree.

Let’s explore one aspect further: having agency within a networked world. To distill things a bit, we can say that there are three major levels of networks. For simplicity's sake, moving forward, we will use the terms “network” and “system” interchangeably.

- Individuals: Human beings in their full complexity and wholeness

- Intermediary institutions: Systems we can belong to and that we can shape, e.g. a family, sports club, impact network, or organisation.

- Societal systems / institutions: governments, the financial sector, etc.

Now, there are connections within each system, e.g. between coworkers of an organisation; between systems of the same level, e.g. organisations within an alliance; and between systems of different levels, e.g. an activist group trying to influence a policy.

We each will have varying degrees of agency in relation to the three levels of networks mentioned above. For example, personally fighting financial injustice, individual level, by ignoring letters from the financial department, societal level, is not the most promising strategy. As individuals, we usually have very little leverage over societal institutions and matters. However, joining an organisation, an intermediary institution, that creates financial literacy among disadvantaged groups and lobbies for policy changes, might actually work.

With an awareness of each level it becomes easier to choose which level and interaction you say yes to and no to. Choices are an opportunity to lean in and engage with the networks within and around us. Yet we may often jump to decisions without being aware of the choices that are available to us. This awareness, from our perspective, is the first step towards reclaiming choice and agency.

Choice for Impact

In engaging choice for creating systemic impact, a key question is: What’s the issue or vision I want to contribute to? To achieve that, what is the relevant system that I want to change, and in which direction do I want to change it? Let’s apply what we’ve learned so far, by drawing on the concepts of choice and agency as well as the three levels of systems. To make this more tanglible, you can bring to mind the situation that frustrates you from the initial exercise, and take a moment to think about the societal issues that underlies it.

To move from inertia to agency, we see four levels of choice.

The first choice is about living into your values and allowing yourself to take your inner compass and drive for social change seriously. This can be in relation to a social issue or external “trigger”, such as observing environmental destruction or diversity loss in your area.

The second choice is to think systemically and be strategic, asking the question: what is the relevant societal system I can engage with in relation to this topic? This choice is context dependent and will vary depending on where you live, the resources you have access to, and which systems may be standing in the way of it becoming a reality. For example, there may be a larger societal system that needs to be shifted, such as the energy supply system with its given sources of energy and the extraction of these resources.

The third choice is to engage my agency and seek intermediary institutions to engage in. It’s a choice to be proactive about changing the status quo with an attitude of both realism, “we should do something or else..”, and optimism, “there is something I / we can do”. Taking the example of climate justice, this might result in joining an energy coop or an activist group to influence politics.

Lastly, the fourth choice is to remember the choices above and embody them with joy and a sense of optimism. We can only be effective change agents if, to paraphrase Gandhi, “our lives are our message”.

Our modern day and age provide us with the unique opportunity to use network effects on a global level to contribute to causes we care about. The Four Levels of Choice can serve as a general orientation, acknowledging that it’s rather circular and interdependent than linear in its application.

Another way we can understand the levels of choice is through imagining an iceberg. Part of the iceberg is above water yet the majority of the iceberg exists beneath the water's surface. The part below the surface represents our values, beliefs and mental models, while the part above the surface represents our behavior and actions. Choice is how we align what is beneath the surface, with what is above the surface, therefore aligning our values with our behavior and actions.

We invite you to go back to your personal situation and example, either for yourself or in the mentimeter survey: How can you relate differently to move from frustration to agency? What are the underlying choices you have?

To give the topic more depth, there are two additional perspectives we’d like to explore, starting with ourselves and the choices we have within.

Choices within

Choice is in essence a process of alignment. At the deepest level choice can be seen as aligning with life, both in a general sense and in the present moment. Through choice we can also engage the intelligence of our body, our senses, organs and our imagination, in noticing what arises in response to a particular direction. Upon waking up in the morning, you can ask yourself ‘what am I choosing today?’ and then notice what arises, not only in the realm of thought, but also through sensations, images, textures, sounds and other experiences. Over time, by cultivating an awareness of how we respond to a given direction, we become able to choose more fully from our whole being and find greater alignment in our subsequent decisions.

At one level these choices within are momentary. They can arise through what we give our attention to, how much we open ourselves to experience something, and how much context to bring in and share with another. Choices can also span time and serve as a north star. For example, choice can manifest through a sense of calling, something we choose again and again that moves us closer to a dream we have for the world. As such, choice becomes the fuel for moving forward. Choice in that sense is an ongoing journey. As we pursue our calling we can reflect on the values we are choosing to enact and the principles we are choosing to embody in service of those values.

Here are some guiding questions to work with choice as an ongoing journey and a calling:

- What is so dear to you that you are willing to choose it over and over again?

- What is choosing you? What are themes you repeatedly run into?

As stated earlier on, our choices reveal our basic attitudes, beliefs and feelings toward life.

Choices underlie our decisions; they move us from thought into action.

Choices in Impact Networks

Yet there is still another dimension of choice, namely within networks or intermediary institutions. We can see these choices through the levels we outlined above as well as in any context where we exist in relation to other beings. An example of this kind of intermediary institution is an impact network, a network that is intentionally created...

Here we can see that there are two fundamental dynamics at play.

In the first dimension such a network coordinates and synergizes individual actions around shared principles and a collective purpose that individuals have chosen to participate in. The purpose of the network may not mirror the individuals’ purpose, however there is usually a synergy between the individuals’ purpose and the purpose of the network.

In the second dimension, impact networks support and carry out collaborative action and learning for deliberative change on social and environmental issues.

Choice shows up in each of the two dimensions within an impact network:

Dimension 1 is about choosing how to create the best possible conditions to engage network members. This requires the network to provide incentives to individuals to actively engage, and at the same time recognise the overall purpose and strategy of the network. For example, establishing rules around membership and criteria for internal decision making.

Dimension 2 is about choosing how to relate proactively to the societal issue and its related system(s). Impact networks, therefore, are an ideal testing ground to practise agency and choice in an intentional way.

Practicing Choice

We’ve seen that the decisions we make are often preceded by an underlying choice we’ve made at a conscious or subconscious level. When we connect with the dimensions of choice we can connect with a greater sense of agency in our immediate context and within the larger systems we are a part of. This awareness, in turn, supports us to become more intentional and impactful in the decisions we make and actions we take.

Choosing is also a capacity that we can cultivate through practice. Throughout each day we can notice the choices available to us and choose to engage our choices consciously. Awareness is the first step. We can practice recognizing the choices we have in the moment as well as the different dimensions that we can engage our choice in. Choosing deliberately increases our agency - the ability to direct our own actions in a meaningful way.

Choices help us to orient ourselves towards the world we wish to create- with all its complex challenges.

It’s a practice, like building a muscle or learning a new skill.

With this article we hope to provide an accessible framework to rethink and reclaim choice & agency, to invite each of us to begin to practice engaging the choices we have, from the large, to the seemingly mundane or small.

The following worksheets are designed to support you in that practice:

- Choosing for impact (4 steps)

- Choosing with my whole being

- Choosing and being chosen: exploring our north star

Download all 3 worksheets in one package HERE

Happy choosing! All worksheets are under a creative commons license, so feel encouraged to invite friends, colleagues and whoever comes to mind into the practice.

About Elsa & Jannik - the authors

This article is a co-creation in the truest sense. We noticed early on in our explorative conversations that we share interests and perspectives on many topics, such as impact networks, creating and evaluating systemic change, and capacity development. We also recognised our complementary backgrounds.

Elsa Henderson is a practitioner at the Converge Network and faculty at the Metavision Institute. She moves between the roles of network consultant, facilitator and educator supporting individuals and groups to deepen their capacity to collaborate for systems impact and find meaning even in the midst of uncertainty. Her background is in process-oriented psychology and anthropology, with an interest in phenomenology, systems thinking and consciousness studies.

Jannik Kaiser is co-founder of Unity Effect, where he leads the area of Systemic Impact Evaluation, grounded in the knowledge that evaluation can be participatory, meaningful and energising. His background is in sociology, with a continuous passion for complexity science, phenomenology and asking fundamental big questions about life.

In our conversations, we also allowed our minds to wander and our intuition to speak. In the end, it felt more like the topic of choice ‘chose’ us. And we could feel the depth and richness in it that is calling for further explorations.

To give one example: The image of the iceberg and choice as a process to align our values and principles and translate them into action. This aligns with the three levels of reality process-oriented psychology, namely (1) consensus reality, (2) Dreamland (inner worlds & imaginations) and the (3) Essence level (the non-dual pre-manifest field of ‘implicate order' as coined by Bohm. It also fits with Ken Wilber’s AQAL model, according to which each system has an interior (invisible) and exterior (visible) dimension.

An interesting exploration could be how individual and collective choices are connected. The iceberg is swimming in a vast ocean of water. Similarly, our individual choices are embedded in what we could call consensus reality or culture. Yet this consensus reality is currently being questioned, and the topic of choice could inform how we transition between such collective realities.

So stay tuned, there might be more coming up.

originally published at Unity Effect

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

Return on Relationships: Four Ingredients of Trust

May 19, 2022Network Support Structures,TransformationBlog,trust

Trust has become something of a buzzword. Most people will acknowledge that it’s important, yet many see it as a byproduct of other activities, rather than something that should be cultivated deliberately.

On the contrary, the web of connections that develops between participants is the invisible structure that holds all types of collaborative communities together, including working groups, networks, and DAOs. A failure to cultivate trusting relationships is where many communities fall short.

Trust is the element that makes possible all of a community’s other virtues and accomplishments. Specifically:

Trust creates cohesion while a community’s more formal structures and processes are being formed. Nascent communities are unlikely to have many formal agreements in the early stages of their evolution. During this time, it may be difficult for some participants to sit with the ambiguity. Trusting in each other and in the group helps people to be more comfortable with emergence—to explore, experiment, reflect, and self-correct in real time. People also become more willing to share information and take risks. Trust is the glue that keeps a group together as participants develop additional structures for organizing themselves.

Trust increases the group’s collective intelligence and avoids the pitfalls of conformism and groupthink. Under the right conditions, groups are capable of thoughtful discernment and collective intelligence greater than that of any single individual. Lack of openness to others’ perspectives is arguably the greatest obstacle to a group's ability to think and act intelligently. Our tendency, in the absence of trust, is to believe that our assumptions and projections are valid, that we know what others are thinking and feeling without asking them, and that maybe we are the only sane person in the room. Trust increases the likelihood that participants will listen with care, try on new perspectives, and engage with people they might consider to be very different from themselves.

Trust expands the range of possible conversations. People who trust each other are more forthright, more likely to share information, and more likely to show creativity in how they collaborate. With sufficient trust, people are better able to navigate through uncomfortable conversations and test each other’s assumptions without fear of harm. As a result, new perspectives are considered, and conflict becomes generative rather than destructive. The group’s ability to engage in constructive dialogue and make informed decisions grows as people feel free to speak their mind and acknowledge difficult realities or controversial points of view.

This shift has been critical to the success of the Clean Electronics Production Network (CEPN), a program of Green America’s Center for Sustainability Solutions, which has been supported by both Converge and the CoCreative consulting group. Participants of the CEPN include many major technology brands and environmental NGOs that are working together to address an issue that no single organization can solve on its own: moving toward zero exposure of workers to toxic chemicals in the electronics manufacturing process. Relationships between the electronics brands and NGOs were initially tense when the network launched in 2016. But over the past few years, “members have gotten to a point where they have enough trust to where they’re willing to share what’s working, what’s not working, and where they need help,” shares Pamela Brody-Heine, director of the CEPN. “Relationships have been transformed, and the communication between them is much more productive.”

Although it is widely accepted that trusting relationships are beneficial when it comes to collaboration, the common assumption is that trust is a byproduct of other activities and that it takes a long time to develop. Rather than deliberately building trust, the norm is to focus on getting to action and letting relationships develop naturally over time.

However, we have consistently found that trust is the single most important factor behind successful collaboration; communities move at the speed of trust. Therefore, trust should be deliberately nurtured from the outset of a community’s development. When working in collaboration with others, the time you spend cultivating relationships of trust is the greatest investment you can make—consider it a “return on relationships.”

Ingredients of Trust

Trust isn’t just a noun, it’s also a verb—it is something you do. It’s a choice people can make. We either choose to trust someone or choose not to trust them (or we can let our implicit biases make the choice for us). While trust takes time to deepen, we’ve found that it is possible to develop a foundational level of trust in a relatively short time.

Trusting another person requires an initial leap of faith, as it’s impossible to know exactly how things will turn out. The unfortunate reality is that by choosing to trust, you expose yourself to being burned. Nearly everyone has been betrayed at some point in their lives, and it can hurt, a lot. It hurts so badly that we might even put up a barrier between ourselves and others so it will never happen again. For some people who have been oppressed or experienced trauma, including intergenerational trauma, trust cannot be easily given—it has to be earned.

And yet, it’s hard to work with people you don’t trust. People collaborate based on relationships, not solely on ideas. Communities run on trust.

There are four primary ingredients that increase the likelihood that people will choose to trust one another, despite all the uncertainty that relationships bring:

- Reliability

- Openness

- Care

- Appreciation

Reliability

Choosing to trust people is, in part, a judgment that they will be true to their word and follow through on their commitments. Trust grows through action. When people help each other by offering support or contributing to a project, it builds a foundation of goodwill. And when people prove their reliability time and time again by continuing to show up, stick around, and follow through, trust grows to a level of resilience that can withstand significant disruption.

Reliability doesn’t mean that people always have to respond positively to a request for support. It’s important that people feel free to decline when they don’t have the ability or capacity to help. Without space for “no,” there is no weight behind “yes.” Being reliable just means that when you say “yes,” you will do your best to follow through and keep others informed if something goes wrong. On the flip side, reliability also means that when you decline, others will respect and hold you accountable to that “no” as well.

Openness

Inevitably, in any relationship, miscommunications and moments of tension will arise. People may strongly disagree with one another about what to do next. Without sufficient trust, these disruptions can derail the relationship and stall action. Overcoming these rocky periods requires openness—the willingness to be honest and share what’s on your mind, as well as the ability to listen deeply and consider new perspectives.

In the absence of openness, our true emotions and opinions are often guarded or hidden under a professional mask. We also remain closed to new information, stubbornly holding on to past beliefs and closing off new possibilities. To be open is to be willing to share honest thoughts and feelings, even if it’s uncomfortable. By being open, we acknowledge interdependence and invite reciprocity. It’s sometimes assumed that being open with one another comes later, after trust has been developed, but openness is also a great catalyst of trust.

At times, being open may simply be too risky. This is particularly true for those who have been oppressed or experienced significant trauma. They know firsthand that people can and do use their power to exploit others for personal gain rather than collective good. For this reason, make sure to allow people the space they need to engage or not, and to honor distance where appropriate. When openness is not yet possible, a mutual commitment to care may be a first step.

Care

For many, trust does not come easily, because past transgressions have revealed time and time again that people are not to be trusted. Often, the first step toward choosing trust comes when people recognize that others hold a mutual concern for something they care about. Even if it’s hard to trust another person directly, it might be easier to trust the love that someone has for their community or region, or for the network.

Critically, demonstrating care also involves acknowledging and then repairing harm. This may mean creating opportunities for those who have been harmed to share their experiences of past harms, and for those who have historically benefited from resources, unjust laws, and the displacement of others to listen, acknowledge the reality of those harmed, take action to repair the harm, and be accountable for doing whatever is necessary to ensure that harm will not be committed again.

Appreciation

To appreciate one another is to accept people as they are and to value different ways of being, knowing, and doing. People often come to networks with very different backgrounds, identities, experiences, and beliefs. A prerequisite to building trust between diverse groups is that diversity is recognized as a critical part of what makes networks thrive; after all, so much of the potential of network building comes from bridging connections across divides.

In practice, a culture of appreciation is one where many different styles and skills are valued and integrated. Deep trust is possible only when people are able to bring their whole selves to the network and contribute their gifts in whatever way they choose. To create a space where all participants are able to contribute fully, it is necessary to ensure that the dominant culture’s norms are not centered to the exclusion of others—in the United States, this means decentering whiteness such that other ways of being, knowing, and doing can flourish.

At an individual level, sharing appreciations also helps to get people out of their heads and into a heart-centered space, creating room for deeper connections to form. This is why we often have people offer appreciations at the end of a convening, asking them to reflect on “who or what are you appreciating right now?” Sharing appreciations in this way serves to reinforce the prosocial behaviors that the network wants to promote.

Trust creates a foundation of mutual respect upon which participants can hold whatever conversations they need to have to begin working together. In forming a community, we don’t build trust so that people will like each other or agree with each other. Rather, we build trust so that people can hold the tension through disagreement and conflict, find common ground, and work together to achieve mutual goals.

David Ehrlichman is a catalyst and coordinator of Converge, a network of practitioners who build and support impact networks. He is also author of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change and producer of the documentary Impact Networks: Creating Change in a Complex World. With his colleagues, he has helped form dozens of impact networks in a variety of fields, and was a founding coordinator for networks in the fields of environmental stewardship, economic mobility, urban revitalization, and Web3. He lives in the Pacific Northwest, finds serenity in music, and is completely mesmerized by his 10-month old daughter.

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

From Learning to Doing

May 10, 2022Social Justice,Self-Organizing,Reflection and Learning,Network Processes,Transformation,BlogTransformation,equity,Systems Change,Self Organizing,Collaboration

Many years ago I was teaching high school English on a small island in SE Alaska. I asked the class to compare a piece of literature to the story of the Three Little Pigs. Half of the class couldn't do the assignment because they had never heard of the story of the Three Little Pigs. That changed me forever.

Without shared experiences, learning communities often talk past each other. Inevitably there is a judgement on one side or the other. Each learner brings his/her own experiences to a conversation and uses those unique experiences to make sense of things. Coming together as a learning community to sort through what we understood from something new that is introduced to us is sometimes very frustrating because of all the different experiences brought to the table. To help with that issue in almost any learning community, you can initiate a common experience/action for all participants. When an action is experienced together, suddenly there is more justice in the conversation. The playing field is leveled and the real conversation can begin.

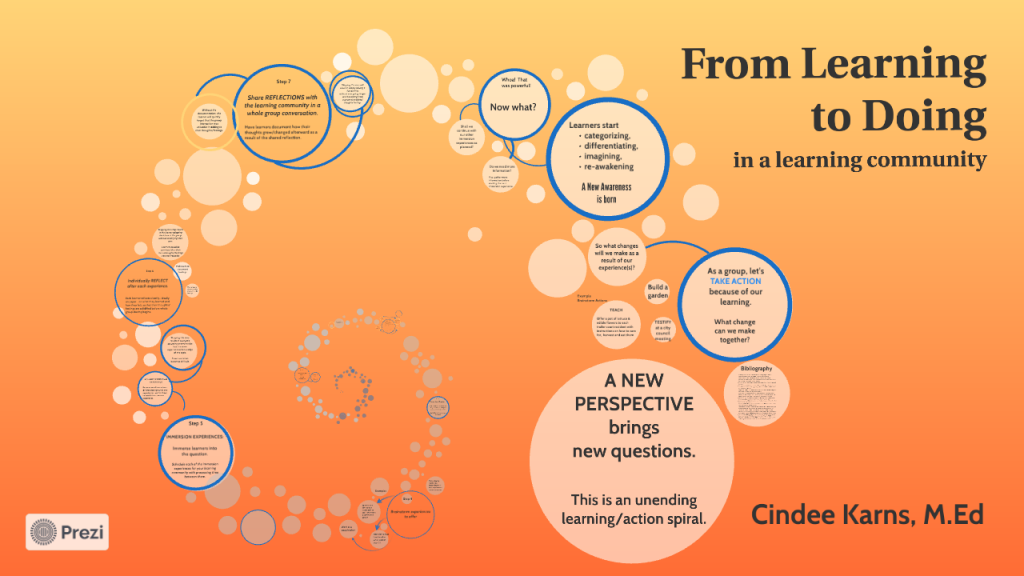

This is a depiction of how that process can be set up for any learning community. The condition is that the learning spiral never ends....every round goes higher, higher. The outcome is that participants almost always feel like they can act on their new knowledge and continue the learning cycle on their own.

Click HERE to access the "From Learning to Doing" resource. A slide presentation on how to create shared experience in a community to initiate actionable change.

Click HERE to access the slide show directly at prezi.com

Cindee Karns, a life-long Alaskan, is a retired middle school teacher with a master's in Experiential Learning. She is founder/weaver of the Anchor Gardens Network, which is attempting to bring increased food security to Anchorage. She and her husband live in and steward Alaska's only Bioshelter

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

The Angel's Mafia: elements to be addressed in peacebuilding governance

April 29, 2022The Big Picture,Network Structure and Governance,Blog,SystemsSystems Change,Governance

Our Better Angels need to get their act together.

I find myself looking back at five years working in peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Almost as long as I spent working as a mechanical engineer in the aerospace field. The business of designing and building spacecraft has one commonality with the “business” of building peace: they both involve people getting together and doing stuff. I used to be weary of the term peace-building as it implies the linear construction of something which can be described as an emergent property of a complex system. What is peace anyway? No, I’m not going down this rabbit hole now, but I leave the open question here for you to entertain yourself with.

You can’t really build peace the same way you build a Falcon 9 rocket. You can’t build the relationships between people the same way you build a clock but you can create the conditions for relationships to emerge, to strengthen and evolve. You can build the scaffolding that makes peace a more likely outcome than violent conflict. A Falcon 9 is just a very complicated clock. Peace is more like a cloud that emerges out of thin, moist air.

Back to my point: I left my engineering career in pursuit of a revelation. And that revelation has come back to haunt me, five years later.

Whether you’re building rockets or building peace, people have to come together and coordinate efforts to accomplish a Mission.