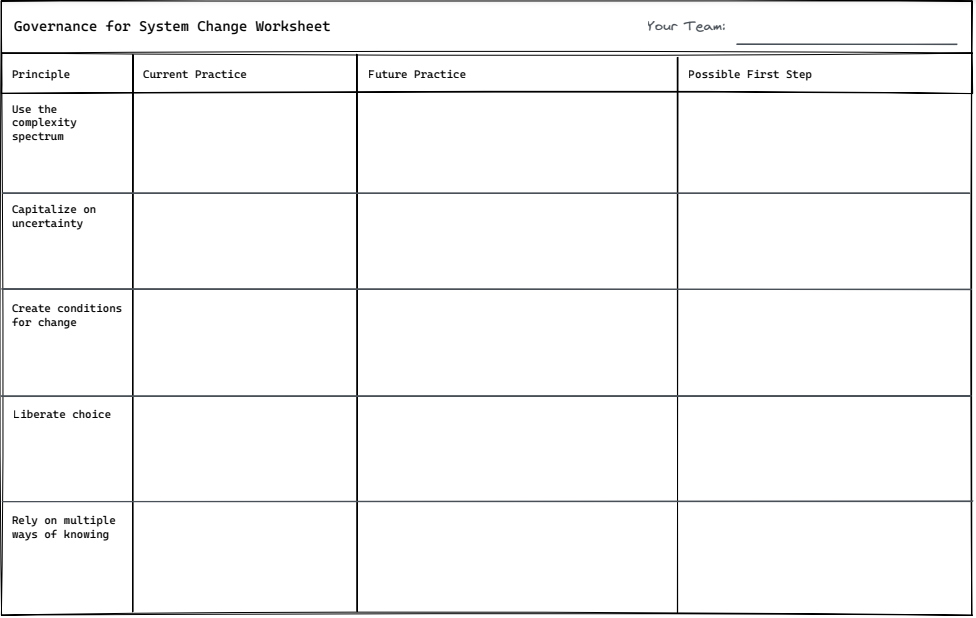

Governance for System Change

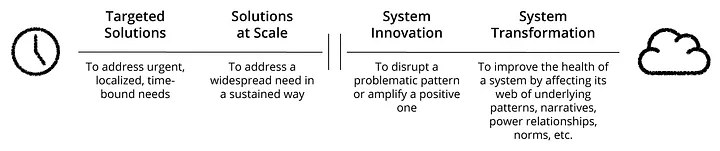

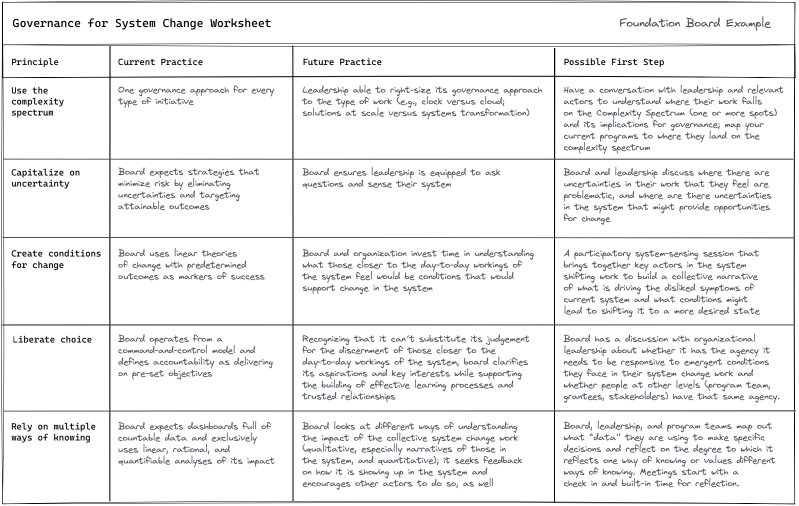

The Complexity Spectrum blog describes how clock and cloud (non-system change and system change) approaches require fundamentally different strategies and tactics. The same goes for the mental models and processes we use to govern system change work.

In fact, governance for system change may not look much like traditional governance at all. Webster’s defines governance as “overseeing the control or direction of something.” Because system change work is emergent, long term and comprised of dispersed and diverse actors, centralized control and oversight is unworkable if not impossible.

Rather, system change work requires distributed decision making in pursuit of a common aspiration and in response to emergent facts on the ground. While centralized control may be impossible, there are ways to bring coherence to this work, increasing the probability of shifting a system to a more desired state.

In this case, governance applies to anyone who makes important decisions that affect the probability of success of a collective system change endeavor, and not just to members of a board of directors.[1] This type of governance is difficult and often requires building a range of new practices over time. Here are a few practices that may help:

- Capitalize on uncertainty to lower risk and increase chances for success.

- Focus on creating the conditions for change over short-term outcomes.

- Liberate choice rather than trying to control it.

- Rely on multiple ways of knowing as you navigate the journey.

Practice #1: Capitalize on Uncertainty

“Uncertainty is an uncomfortable position. But certainty is an absurd one.” -Voltaire

Depending on where you engage on the Complexity Spectrum, uncertainty can be a problem or it can provide a valuable opportunity.

Targeted solutions require a technical approach where you move efficiently along a mostly known pathway from a known problem to a known solution. Take for example a population that has been displaced by a natural disaster. We have experience dealing with this type of situation (known problem) and delivering the targeted solution of emergency shelter (known solution) though various tried and true means (mostly known pathway). In this case, uncertainty can be disruptive because it creates barriers between the problem and the solution.

Solutions at scale usually require an adaptive approach (think Human-Centered Design).

For example, in California many more people were eligible for benefits to alleviate poverty and food insecurity than were applying for them. The reasons why the problem existed were fairly well understood (sufficiently defined problem). In response, Code for America talked to people to understand why they weren’t applying and how they could provide a solution. They built an app, iterated it, and eventually launched a product (GetCalFresh) that greatly increased the number of eligible people applying for benefits (iterated to find a solution that was initially unknown).

An adaptive approach requires a fair level of certainty about the definition of the problem and its causes — enough to support a process of managed uncertainty in which you experiment to find deeper causes and solutions to the problem.

System transformation calls for an emergent approach.[2] In an emergent approach, while you are likely certain about the negative symptoms of the challenge (e.g., high levels of poverty or inequality), the deeper drivers of the problem and reasons for its persistence are mostly unknown or misunderstood. Consequently, the ways to address these drivers are also mostly unknown (or unformed). The key is to nurture the conditions that will support the system healing itself (e.g., understanding the systemic drivers of the challenge and supporting the emergence of ways to address them).

In an emergent approach, uncertainty unlocks opportunity. When complex challenges persist over time despite efforts to address them, there is often a sense of frustration, even despair. However, this can lead to the realization that we don’t have all the answers, which can make us more open to thinking differently.

Some forms of systemic analysis, like dynamic system mapping or participatory futures, provide a structured process for thinking in new ways about an all-too-familiar problem. When doing participatory system mapping, aha moments often arise when participants identify a pattern that explains why change has been elusive. It is empowering to see an old problem from a different perspective and find a possible path forward.

Effective system sensing should lead to confidence that you have “good uncertainty” — or trust that there are good questions to explore and a way to experiment and learn more about the system and how to engage it. Think of uncertainty as a gateway to doing things differently and finding ways to unstick a stuck system.

Practice #2: Focus on Creating the Conditions for Change

Uncertainty is uncomfortable because it increases our fear of failure. It makes us anxious. One common but ultimately unhelpful response is to over-rely on short-term substantive outcomes that are a small piece of the ultimate outcome we want to see. [3] For example, if we are looking to end human slavery in global supply chains, we might measure progress by looking for annual percentage reductions in the estimates of slave labor by 5% or so each year.

It is wise to understand the impacts our work is having in the short term, if for no other reason than to detect and mitigate potential negative impacts. However, there is a danger of using pre-defined, substantive outcomes as waypoints to navigate our way on the journey toward long-term system change.

Specifically, there are two key dangers:

- Short-term outcomes dominate our time, attention, and resources and reduce commitment to long-term change. According to neuroscientist Ian Robertson, “success and failure shapes us more powerfully than genetics and drugs.” This means short-term successes can lead people to invest more time, resources, and emotional commitment in concrete short-term outcomes instead of longer-term, hazier systemic shifts. Moreover, grantees often need to trade annual impacts for continued funding, so pre-identified short-term outcomes take priority.

- Short-term impacts can be bad predictors of long-term, systemic impact. In complex systems, impact is not static. What may seem like a good outcome in the near term, might drive negative downstream impacts in the months and years ahead. Basing future investments mostly on short-term outcomes can lead to bad long-term investments.

The implication is an inexorable pull away from making the hard choices and risk tolerance needed for system change. As a result, the pursuit of specific substantive outcomes in the short term may make it more likely a system change effort fails in the long term.

Fortunately there is an alternative. Alice Evans, who in her time at Lankelly Chase helped build their systems practice, said a key enabler of their work was the realization that creating the conditions for system change should be their focus rather than targeting specific outcomes those conditions might produce.

For example, there are a few generic conditions that will apply, in some form, to most system change initiatives. These include the degree to which important system actors can:

- See their context as a complex system and use that shared understanding to inform action and increase the potential coherence of distributed action.

- Identify and engage patterns that people believe will unlock change (e.g., weakening patterns that sustain the problem or strengthen bright spots that can shift the system).

- Build or strengthen connections, networks, and information flows across the system.

- Build an infrastructure for learning and, as Marilyn Darling says, “return that learning to the system.”

Elaborating these and other conditions that might support system change requires a participatory process that prioritizes the voices of those closest to the day-to-day operations of the system.

As we look at the conditions we are trying to cultivate, we must also look at those in ourselves and in our organizations. We are all part of the respective systems we are engaging and it’s critical to contend with power and who is making decisions both within an organization and in a broader system impacted by those decisions. If you haven’t already done work on your own relationship to power and how it impacts your work, now might be a great time to dig in. Consider asking:

- How are we showing up in the system? What feedback are we getting about how we’re showing up? Are we working in a system-informed way? How do others experience our presence?

- What is the quality of our relationships with other key system actors? How have we prioritized the voices of those closest to the context?

- How do we understand our own power in the context we are working in and the people we are working with? How do others perceive it? How can we engage others in an honest conversation about our relative power?

Fortunately, changing how we show up in a system shifting initiative is a condition over which we have the greatest control. Unfortunately, many of us, especially funders, show up in ways that replicate or entrench unhelpful power dynamics that constrain choice and make distributed decision making impossible. This means a critical early condition for system change is understanding and adapting the ways in which our organizations — and even ourselves — work. For more thoughts on internal organizational conditions and how to work toward them, see Building Emergent Organizations.

Practice #3: Liberate Choice

Successful system change requires those closest to the day-to-day operations of the system to be highly adaptive over time in response to emerging realities.[4] However, this is hard to do with traditional governance processes that seek to maximize control and minimize risk.

For example, a standard grant agreement trades funds for outcomes identified by the donor, which replicates the power dynamic of “those with resources call the tune.” This dynamic too often prioritizes donor interests rather than those most impacted by the funding, removes agency from those closest to the context, and creates highly transactional relationships.

If funders behave in ways that reduce the agency of these actors, they inhibit their ability to work for system change.

The alternative to donors limiting choice is to use what Cyndi Suarez calls “liberatory power,” or the ability to “create what we want” by transforming “what one currently perceives as a limitation.”[5] A key question for donors wishing to support system change is, how can we increase the ability of key actors in the system to effectively connect with each other, sense, sense-make, act on, and learn from their system?

Each level of actor in a system change initiative can liberate the choices of actors in the system. Liberating choice is not the same as giving more choices — it requires both the presence of choice and the agency to act on it. A board of directors needs to liberate choice for organizations they oversee; leadership of an organization needs to liberate choice of its program teams; program teams need to liberate choice of grantees and partners; grantees and partners need to liberate choice of stakeholders and community actors; and based on how information flows in the system, stakeholders can liberate choice for program teams, etc.

This is not the same as simply giving money and getting out of the way. Liberating choice does not mean removing all structure. Many argue there is no such thing as structurelessness when it comes to any kind of group activity, especially when one actor is providing significant resources to support the work of other actors.[6] Donors need to provide enough structure to enable choice, but not so much as to prematurely curtail choice.

The key is to create minimally sufficient, helpful structure. For donors supporting system change, there are some key components to creating minimal structure, which include:

- Articulate a common aspiration or guiding star.[7]

- Clarify boundaries by articulating key interests and values.

- Establish an infrastructure for learning.

- Invest time in building trusting relationships among system actors.

Of these four points, clarifying boundaries or guardrails may be the most difficult. An unhelpful but familiar way of doing so is to provide directives to either do or not do something. A more useful approach is the “even-over statement” as developed by Tom Thomison and popularized by Aaron Dignan.

The benefit of even-over statements is that they share how different actors in the system might make tradeoffs between key interests and values. The statement consists of two “good things” and says, “if confronted with a choice, I would choose this good thing over that good thing.” However, it aims to preserve the agency of an actor to make a decision in light of the specific situations that they find themselves in.

Some generic even-over statements that liberate choice for system change include:

- Prioritize responsible, smaller experiments even over concentrating resources on large-scale bets.

- Invest time in building trusting relationships even over delivering on preset timelines.

- Value responsible learning even over clear-cut wins.

- Foster regular, honest feedback across the network of actors even over preserving harmonious relations.

Whatever boundaries you try to set, and however you set them, they will be wrong in some respect. This is where a dynamic learning process is essential. Part of that learning process needs to ask to what degree are the boundaries and common aspiration helpful? In what ways are they affecting people’s thinking and behavior? Are they strengthening agency of system actors or reducing it? What might we do better?

And none of this works if the relationships between actors in a system change initiative are mainly transactional. Because system change work is highly emergent, it requires real time and honest communication and the ability to work in a decentralized way. All of this requires high levels of trust between actors, and this level of trust does not happen unless they invest time in it. This can be particularly difficult for funders who see investing time to build trust as simply increasing overhead.

Practice #4: Rely on Multiple Ways of Knowing

“There is a strong bias in the U.S. dominant culture, one that shows up in the nonprofit sector as well, to value only one way of knowing, the one grounded in data, analysis, logic, and theory — a rationalist’s approach to truth.” -Elissa Sloane Perry and Aja Couchois [8]

Working effectively in complex systems requires strengthening our ability to use multiple ways of knowing. It is essential for implementing the practices described above. Unfortunately, as the quote from Elissa Sloane Perry and Aja Couchois indicates, the default capacity for many in the West is to privilege only one way of knowing — a cognitive, analytic approach.

This is not to say we should devalue rational analysis. Rather, it means putting a high value on the ways others understand their world and make decisions about how to act.

There are various ways to define multiple ways of knowing, from Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences to the model of five minds described by Tyson Yunkaporta.[9] A simple way to look at multiple ways of knowing is: thinking, feeling, and intuiting.[10] At a minimum, it means asking: what do you think about the situation, how does it make you feel, and what is your gut telling you to do? It means listening to how others think, feel, and intuit.

Listening to feelings and intuitions is not the same as following them. Rather, it means understanding how information, situations, and decisions make us and others feel; allowing our intuitions to come to the surface; and not automatically subjugating these to what we might judge as rational or rigorous analysis. It means sitting with differences and uncertainty and valuing the important stories people tell about their system, and not just the numbers they can fit on a spreadsheet.

For many, this is the most disruptive practice for system change governance. It requires us to change how we think about and develop strategy, how we evaluate our effectiveness and that of our grantees, and how we make decisions. It means that good questions are often more useful than seemingly good answers. Fundamentally, it changes how we know what we know (e.g., how we weigh a quantitative analysis versus the lived experiences of partners on the ground).

But as disruptive as it can be, cultivating multiple ways of knowing is worth it. There are several reasons why: from the neuroscience that shows the role of emotions in decision making to the necessity of multiple ways of knowing for advancing equity.

In addition, there are simple, practical arguments for cultivating multiple ways of knowing from a system change perspective:

- If shifting systems involves diverse actors spread across geographies and cultures, different ways of knowing will always exist in the network. This means effective system change work requires the ability to understand and work with those different ways of knowing.

- And, because complex systems are murky and constantly changing, it is naïve to rely on only one way of knowing. Each way of knowing has limits but, together, multiple ways of knowing increase our effectiveness.

- Lastly, multiple ways of knowing are essential because we can’t just reason our way to system change — rather it requires a dynamic connection between head, heart, and gut.

One accessible way to start bringing multiple ways of knowing into your work is to play with meeting structure. Try starting meetings with a check-in question like “how are thinking and feeling coming into the meeting?” Or you could ask something more playful like “what was your favorite movie character as a kid?” A more serious question could be “can you describe a time when you felt truly happy?” Think of it less as an icebreaker and more of a space for people to welcome in their whole selves and deepen relationships. It also helps to build in time for silent reflection in the room, have people journal, or to pair up and process the meeting while taking a walk.

Many people have built more in-depth ways to incorporate multiple ways of knowing. A few I suggest are: the Equitable Evaluation Initiative, for using multiple ways of knowing to build more equitable evaluation processes; Relational Systems Thinking: That’s How Change Is Going to Come, from Our Earth Mother by Melanie Goodchild, for how to realize the benefit of differing world views and ways of knowing; and Theory U by Otto Scharmer, for a comprehensive approach to system change that has multiple ways of knowing at its core.

Next Steps

Learning to use a different frame for how we govern system change is a practice, and it takes time to develop. Devoting time to consciously changing your governance practices is the first challenge you will confront. But remember, systems seldom change on a dime, and neither do we. You might want to start with the system you know best and are closest to — you and your own organization.

One way to start is to use these governance practices as a set of prompts for your own self-reflection and experimentation, such as:

Using the Complexity Spectrum. How are we differentiating among our organization’s approaches along the Complexity Spectrum? Are we developing different mindsets and practices for clock versus cloud initiatives (e.g., solutions at scale versus system innovation or transformation)?

Capitalize on uncertainty. How are we cultivating good uncertainty and capitalizing on it? Are we resisting the urge to create certainty when there is none?

Liberate choice rather than trying to control it. Do those closer to the context feel they are able to make the choices needed to engage the system effectively? How well are our aspirations, guardrails, and learning processes helping us learn from the choices we make? What levels of trust are we able to build?

Focus on creating the conditions for change. What are the conditions that will support change in our organizational system? How well are we supporting them? How might we revise them? How are we understanding what others in the system feel are the conditions that will drive change?

Rely on multiple ways of knowing as you navigate the journey. Are we getting in touch with our own ways of knowing and cultivating openness to others? Are we trying both small and large experiments? (e.g., creating space in meetings for check-ins and reflection time? Building a more equitable evaluation practice or sitting in the tensions between different world views?)

Lastly, give yourself and those around you room and permission to change. Rather than expecting to get it right, focus on getting it better. Together I think we can do just that.

Download a PDF of the blank worksheet

Download a PDF of the example worksheet

Acknowledgement: While I take responsibility for the words used in this blog, the ideas come from dozens of colleagues, hundreds of conversations, and thousands of hours of experimenting and learning by many.

[1] I will often refer to the work of a foundation board because this is the context I know well.

[2] I am using the terms technical, adaptive, or emergent approach instead of technical, adaptive, or emergent strategy to avoid confusion with established writing on these types of strategy. There is a fair amount of commonality of usage of the terms technical, adaptive, and emergent between this piece and earlier works, but there is not 100% overlap and I want to avoid confusion or to imply that I am redefining these types of strategy. For writing on the subject, see the works of Ron Heifetz, Adrienne Marie Brown, and Henry Mintzberg.

[3] In this case, substantive outcomes mean measurable changes to the symptoms of the problem we are concerned with, as opposed to the process by which we work.

[4] This is particularly important when working with complex systems where those closest to the context need the ability to respond to what they are learning. This is what Gen. Stanley McChrystal found in doing counterinsurgency work and wrote about in his book, Team of Teams. McChrystal saw the need to empower choice from units on the ground by creating more distributed decision making.

[5] See The Power Manual by Cyndi Suarez, p. 13.

[6] See The Tyranny of Structurelessness by Jo Freeman who wrote about organizing the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s. Here is a relevant passage: “Contrary to what we would like to believe, there is no such thing as a structureless group. Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power, and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved.”

[7] For guidance on developing a guiding star, see the Systems Practice Workbook.

[8] Multiple Ways of Knowing: Expanding How We Know, April 27, 2017, Non-Profit Quarterly.

[9] Here is a quick description of the five minds.

[10] Here a quick explanation of the science of intuition: “Intuition is a form of knowledge that appears in consciousness without obvious deliberation. It is not magical but rather a faculty in which hunches are generated by the unconscious mind rapidly sifting through past experience and cumulative knowledge.”

Rob Ricigliano is the Systems & Complexity coach at The Omidyar Group, where he supports teams as they engage complex systems to make societal change.

originally publshed at In Too Deep

featured image by kazuend on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

Decentralized organizing: More collaboration, less hierarchy

From organisational governance to mobilising and sustaining grassroots movements, what is decentralised organising and how can this approach facilitate collective but efficient decision-making without management hierarchy?

Decentralised organising isn’t just about delegating tasks and responsibilities. It’s about transparency and openness, including how financial decisions are made and how labour is divided. This approach creates a great work ethic:

- Empowering members to do the work they care about, not just what they’re told to do

- Cultivating a culture of trust, collaboration and transparency

- Incentives are aligned because ownership is open to all

Sounds good? We recently caught up with Rich and Nati from Loomio while they were in London and discussed some useful decentralised organising approaches. Here are some changes you can easily implement to start working more collaboratively with less hierarchy:

Establishing “ground rules”

Norms are informal agreements about how group members should behave and work together, e.g. open, honest, inclusive. Boundaries are behaviours that we want to exclude, e.g. no mean feedback, exclusionary decision-making. Collectively, norms and boundaries can also be referred to “ground rules”.

Take time to listen to each member’s perspective. Then, as a group, decide on what your shared norms and boundaries will be. Finally, have this documented and accessible to all members and new members so that expectations are clear and transparent. This way everyone is bound by the same ground rules.

Communication norms

Open but efficient communication is a cornerstone of successful and strong relationships. It can be built by establishing communication norms and collectively agreeing on what communication tools to use for what job. For example:

- Realtime: like whatsapp chat: Informal and quick, it’s about right now.

- Asynchronous: Email or Loomio. More formal, organised around topic. Has a subject + context + invitation. Can take days or weeks.

- Static: Google Docs, Staff handbook, or FAQ. Very formal, usually with an explicit process for updating content

An understanding of when to use different communication tools avoids clogging up communication channels with unnecessary information. Finally, it is important to support members to learn how to use tools and remind each other gently to build habit.

Sharing is caring

Hierarchy habits such as having the same chair for team meetings can discourage other members to feel that they can bring ideas forward, participate in decision making, and take leadership. It is important to be intentional about the behaviours you want to bring to your organisation or network so that members trust each other and feel comfortable working together:

- Intentionally produce a culture of trust and belonging by sharing power, enabling lots of time for discussion, for natural leaders to be reminded to hold back and let others talk,

- Growing collaboration skills with practice through empathy, reflection and communication. It helps to have 5 mins reflection at the end of the meeting to ask people how they think it went – OR send out an anonymous reflection form just after the meeting to see how it performed against the organisational values.

- Distribute ‘care’ labour: make care work visible so that it can be fairly shared – this includes things like organising biscuits to setting the agenda.

Decentralised organising in practice: The Lambeth Portuguese Wellbeing Partnership

In this next section, we feature the Lambeth Portuguese Community Wellbeing Partnership (LPWP), a grassroots community network of over 40 local groups and community members. Bringing together organisations and people from across the health, social, charity and voluntary sectors to listen and work together, the LPWP is an exciting example of working in partnership through decentralised organising to help the Portuguese speaking community live healthier lives and to remove the barriers they face accessing health services. The partnership are keen to work towards adopting a decentralised organising approach and are on a continuous journey to work towards greater transparency and collaboration to create change.

Their successes and impact so far include

- A Breakfast / Homework Club run in conjunction with a Portuguese Café, a local school, educational charities and the NHS.

- A GP surgery and a voluntary sector organisation carrying out joint assessments of frail and vulnerable patients, with the voluntary community liaison officers providing care-coordination and links into social support.

- End of life and Latin American disability charities working together to modify advance care planning templates, empowering those at the end of life to make the decisions that are important to them.

- Culturally relevant patient leaflets, education videos and an NHS ‘Welcome Brochure’ in Portuguese, informing patients of their NHS rights and self-care options.

- A children’s charity working with scientists, to provide children from vulnerable backgrounds experiences working in science in universities.

The LPWP commissioned the Social Change Agency to support developing a strategic and decentralised organisation framework that will ensure that the partnership can play an active role in helping people with multiple long-term conditions live fulfilling lives for longer. It was a great pleasure to meet and interact with some of the organisations and individuals within this partnership, their passion and commitment to working together through values that include inclusivity and trust to improve the wellbeing of Portuguese speakers in Lambeth is truly inspiring!

If you want to focus was on moving towards flatter hierarchies, grassroots decision-making, and letting go of traditional hierarchies, then get in touch to find out how we can help.

The Social Change Agency is an expert team of strategy consultants, campaigners, communicators, and governance geeks. They’ve launched powerful movements, built innovative networks and led groundbreaking campaigns - their expertise spans every aspect of social change.

originally published at The Social Change Agency

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Reframing Power and Embracing What is Possible

Lighting the Candle of Liberatory Governance

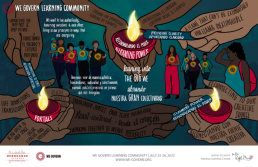

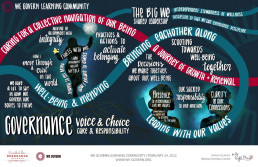

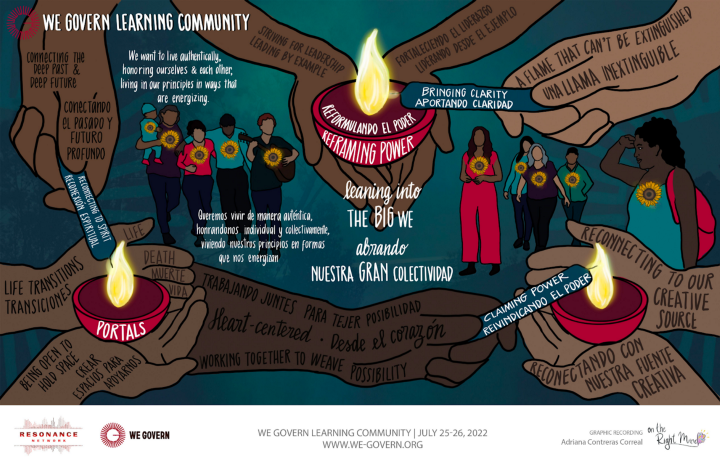

As phase two of the WeGovern Learning Community winds to a close, participants gathered to reflect on their journey.

This community came together with a shared commitment to practice liberatory governance — and we did. Participants—including Resonance Network, who convened the learning community space but practiced as a participant team—reimagined what governance beyond dominant power structures could look like in our organizations, tribes, networks, and teams.

And what came through as we reflected on the experience was not only the transformations that took shape externally within these groups, but internally among participants as well.

Our choices add up to the world we’re building — and once you feel the power and possibility in choice making and community building from a place of liberation and care, you can’t turn back. We all felt that.

Our commitment to governance practice kindled a deeply felt sense of what is possible.

The process of embracing WeGovern—a set of governance principles rooted in mutual care, dignity, and thriving–in our own lives—helped each of us realize that we have more agency in the choices we make to live from our values than we realized.

Of course, the systems of control and domination we live within want us to believe that power exists outside of ourselves — but the opposite is true. Our choices add up to the world we’re building — and once you feel the power and possibility in choice making and community building from a place of liberation and care, you can’t turn back. We all felt that.

This practice became an affirmation that governance begins with each of us — in the choices we make each day to engage with ourselves, each other, our families, and our communities.

Bringing clarity

Each of us felt this sacred responsibility — an embodied knowing that developed in the practice. We described it as “a bell that can’t be un-rung” or similarly, “a flame that can’t be extinguished.” Once we felt that sense of agency in choice making — and began to witness the ripple effect of transformation in our communities — we couldn’t go back to business as usual.

But the future we are moving toward isn’t completely unknown to us — it lives in our lineage, in the memories of our ancestors, in the wisdom of the land that sustains us, and in the relationships we are building with one another.

Instead, we find ourselves choosing to move into the unknown — away from what has been familiar, and toward what feels whole. The future we are moving toward is unknown — it is unknown to the collective systems we live within that have shaped so much of our lives, profited from limiting our perceptions of possibility, and capitalized on dulling our sense of collective purpose. But the future we are moving toward isn’t completely unknown to us — it lives in our lineage, in the memories of our ancestors, in the wisdom of the land that sustains us, and in the relationships we are building with one another.

Reconnecting to spirit

The sacred responsibility of this way of worldbuilding, the connection to lineage and ancestral memory–bringing the wisdom of what was into what will become–is spirit work. It is work that requires tending to sustain it, but also sustains us. We seek spirit the same way sunflowers seek the sun.

We seek connection to spirit not just to ask for what we want, but to remind us of our humanity, our power, and our clarity in service to a higher purpose–a world where all beings can thrive. And that world is taking shape each day, in the relationships between us. If we are the candles that cannot be extinguished, our connection to spirit and purpose kindles the flame so that we can light other candles.

Claiming power

The flames we tend are a reminder of our power. The power that naturally comes from connection to source and purpose. The organic current of creative energy that flows when we’re in alignment with purpose and care. Despite the ways oppressive systems try to diminish our power, we are transforming ourselves, our communities, and our collective systems.

We claim our power when we see ourselves within the system–when we see and feel the way our agency, our choices can be used to change it. When our individual agency and power becomes collective. We claim our power when we refuse to be separate–from ourselves, from each other, and from the generations that came before and will come after us. When we accept the sacred responsibility of choosing the way we want to be, in alignment with the world we want to live in.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Being in the humanity of governance, with all its messiness and joy

Reflections from the WeGovern Learning Community

How do we build ways of being that uplift the collective dignity, wholeness, and thriving of one another and the lands we inhabit?

How do we build ways of being where our collective wellbeing is carried by community?

How do we create opportunities to live a happy life? To find joy?

WeGovern Learning Community participants are exploring these questions together–discovering what it takes to live into the WeGovern principles today, in our current realities and communities.

This is collective governance, and it takes practice.

* * *

In phase two of the WeGovern Learning Community, a cohort of new and returning participants came together with a shared commitment to collective governance–in practice, embodiment, and reflection. In their first gathering, cohort members delved into what governance means to them, and how it shows up in their lives. Here are some highlights from that conversation:

“I am a movement within myself.” ~ Monique Tú Nguyen

- I used to think there wasn’t a clear rhythm to the way I make choices–that it just sort of happened as things came up. But when I reflected on it, I realized I have a methodical way of making decisions–with myself, choosing who I spend time with and what I spend time doing, and how I care for myself and use my resources emotionally, physically, spiritually, and financially. That’s governance, and there is power in that clarity.

- At work, we have to be clear about documentation; there are clear pathways and decision making protocols–but how are we clarifying, for ourselves, the pathways toward decision making in our own lives, and in our interpersonal relationships?

We are stepping into the sacred responsibility of tending to our own being-ness

- If we are going to be in relationship and connection with others, we have a responsibility to tend to our own being–our own healing, our own growth. Everything else comes from that place–our practices, our placemaking, how we cultivate belonging, and how we become aware of our needs–and make choices to make sure those needs are met.

- It is the values and choices that I practice every day, in all the unfolding moments. I am choosing wholeness and listening and vulnerability

“When I think about the ways I engage with governance the most, it’s in the relationships I touch every day–my relationship with myself, my relationship with my dog, my relationship with my partner, and in my caregiving relationship with my mom, who has dementia.”

-Alexis Flanagan

There is power in visibilizing our governance practice(s)

- And it’s important to name governance as governance — to visibilize our practice, so we can bring people along

- We are cultivating a sense of responsibility for the way we move through the world. From the moment we get out of bed in the morning, how are we living our values? It’s so easy to let that process be invisible, but so important to bring it to light.

Governance is the gas pedal on the tractor

- If I imagine my life as driving a tractor, what’s accelerating me forward is my own choices. I want to move forward in alignment and with integrity, so that my thoughts and feelings and actions are all in harmony with each other. And I feel right with myself.

- Meanwhile, it’s important to make sure that I am being transparent about my choices in the world–because it’s not enough for me personally to just do the thing. If I don’t voice the value I’m living into, people may see what I’m doing but not understand why. We have a responsibility to bring people along.

“We are scootin’ toward the interdependent stewardship of wellness” -Aaron Spriggs

- Governance is about the big ‘we’. When we understand we as ‘all of us together,’ we consider the moves we make–and the way we impact each other–differently

- Governance is stewardship; it’s caring for the collective navigation of our beingness.

- Our decision making together brings in every part of us, and all of the ecosystems around us into how we’re making every single choice, how we’re moving through our days.

“I am honoring and orienting towards wellness and nourishment–and I practice that in how I speak internally to myself, how I choose to speak in a shared place, how I choose to navigate things like making food in my kitchen–all the choices I make that are interconnected with other people, that impact me and the people around me are all part of that building out into the world we want to live in.”

-Reese Hart

Collective governance is a discipline we choose, so that all people may experience dignity

- We are building strategies to prevent future harm while also taking time to imagine what governance looks like outside of the current structure we live in, that continues to cause harm

- To govern, you need to think about what breaks your heart. And also what you love–and that’s going to help you be who you are in the world. — Rose Elizondo

Governance is a lifelong journey

- Just as in nature’s rhythm of seasons, we are renewing ourselves constantly–our needs are not the same, moment to moment; our bodies are not asking for the same things

- Being able to be open and responsive in the natural ebbs and flows is part of governance practice–it is an ongoing journey of renewal and growth

Governance is the restoration of birthright

- All of us are part of a lineage–we are coming back into ourselves and our humanity, choosing and creating the life we want to live, with the people and beings we want to be with. Almost like we are revisiting our childhoods and getting to raise ourselves–we are deciding who we are, who we want to be, and how we want to relate to (and with) others. How we want to be seen.

- And the capacity for this is something we’re all born with–we don’t have to achieve or acquire; our capacity for governance is already within us. And the more we can see that, the less alone we feel.

“This enormous world I’m part of is always going to be big enough for whatever I evolve into.” -Yesenia Veamatahau

The stance, self care, investment, and spaciousness to be present to what’s happening around us. To step into the choices, in each moment, that enable us to live our values, we need to be present to connections, community, and portals–like the land. Land connects us to today, tomorrow, yesterday. We need to breathe into compassion, boundaries, and love.

We are learning to really be with ourselves–and witnessing the ripple effect that has on others.

Collective governance is rooted in Indigenous peacemaking and restorative justice practices, incorporating laws of nature and spirit.

Forrest Landry says that love is that which enables choice. And perhaps the same is true for governance that Dr. Cornel West says about justice–that it’s what love looks like in public. Governance is ultimately a collective practice–one we are delving into in times of deep uncertainty, isolation, and struggle. We are building when we need to most, the kind of governance we know is possible. Beginning with the choices we make today.

* * *

The reflections in this post were shared during the first gathering of the WeGovern Learning Community Phase 2. Just as the governance we practice, this discussion was a collective endeavor. Deep gratitude to all participants for their presence and contributions: Benjamin Carr, Reese Hart, Monique Tu Ngúyen, Crystal Harris, Ed Heisler, Sarah Curtiss, Leta Harris Neustaedter, Aaron Spriggs, Judith LeBlanc, Lonnie Provost, Brittany Eltringham, Heidi Notario, David Hsu, Adriana Contreras, Estefania Mondragon, Jenni Rangel, Ruby Mendez-Mota, Jovida Ross, Shizue Roche Adachi, Alexis Flanagan, Aparna Shah, Doris Dupuy, Kassamira Carter-Howard, Megan Shimbiro, Yesenia Veamatahau, Karen Tronsgard-Scott, Anne Smith, and LaToria White.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

The Angel's Mafia: elements to be addressed in peacebuilding governance

Our Better Angels need to get their act together.

I find myself looking back at five years working in peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Almost as long as I spent working as a mechanical engineer in the aerospace field. The business of designing and building spacecraft has one commonality with the “business” of building peace: they both involve people getting together and doing stuff. I used to be weary of the term peace-building as it implies the linear construction of something which can be described as an emergent property of a complex system. What is peace anyway? No, I’m not going down this rabbit hole now, but I leave the open question here for you to entertain yourself with.

You can’t really build peace the same way you build a Falcon 9 rocket. You can’t build the relationships between people the same way you build a clock but you can create the conditions for relationships to emerge, to strengthen and evolve. You can build the scaffolding that makes peace a more likely outcome than violent conflict. A Falcon 9 is just a very complicated clock. Peace is more like a cloud that emerges out of thin, moist air.

Back to my point: I left my engineering career in pursuit of a revelation. And that revelation has come back to haunt me, five years later.

Whether you’re building rockets or building peace, people have to come together and coordinate efforts to accomplish a Mission.

People have to get themselves organized. If it’s the rocket they’re building, the way of organizing is pretty straight forward. It’s a linear process. We’ve been building rockets for quite some time now and have learned a lot about how to do that efficiently. There are still some hiccups every now and then. When these happen, it’s up to the skills and mastery of the project manager (PM) and systems engineers (SE) to make sure they don’t compromise the Mission. The Mission is sacred. You may be an expert planner but as a PM, you’ll be judged by how creative you are when dealing with the hiccups: a delayed supplier, a volcano eruption, a failed test, a new requirement, a pandemic or a world war. The best PM’s I have met in my previous life were those that knew that you need to be ready to deal with contingencies and uncertainty. This is where a good governance system comes in handy. Running the day to day operation of an engineering team requires discipline, practice, expertise and structure. You’re inside a bubble of control. When this bubble bursts and the outside world comes barging in, you need something different. You’re operating in a different regime. The outside world is complex. Full of interconnections and invisible, mysterious forces. Enter the Law of Requisite Complexity which states that “In order to be efficaciously adaptive, the internal complexity of a system must match the external complexity it confronts.” And this was my revelation back in the day: management is different from governance! Management is all about the plan. Governance is about dealing with situations where the plan that you had is no longer the plan that is needed.

With the exception of perhaps the mafia or terrorist neworks, we don’t know how to organize in an enviroment of complexity and uncertainty. Since we enter kindergarten (and perhaps even earlier through models unconsciously passed on by our parents), we are conditioned to think that someone else, a parent, a teacher, a headmaster, a boss, a political leader, a country, a government, an institution, an NGO, you name it, must have The Answer. someone must have The Plan. Someone must have An Understanding of what is going on. Someone will manage it!

When faced with problems that, by definition, have no well defined problem-statement, no boundaries, no solution, we revert to this very rudimentary, almost medieval governance system where a few (typically old, white) men call the shots for all of us. I have nothing against old experienced men calling the shots sometimes (they may have some clever ideas), but I am against this being the only form of social organization in complex environments.

The peacebuilding world has taught me a lot about what it takes to thrive in a complex and ambiguous environment. If you survived a civil war and are engaged in local peacebuilding, you’re pretty much an expert in the Vuca World. I struggled to find my voice in this field. After all, what do I know about peace? I have never heard an AK47 fire.

I found my voice in the overarching theme of social organization and governance. When complexity and uncertainty (aka real life) bursts through your control bubble, that’s when investing in a governance system that obeys the law of requisite complexity makes it or breaks it. After five years witnessing the efforts of 24 South Sudanese Angels coming together for peace, here are a few elements I believe should be addressed when thinking about governance systems.

Communication, language and meetings

Communication is the essence of human social organization. For better and for worse, we’re doomed to use language to communicate and coordinate with one another. The pandemic zoom years have shown us that, while it is possible to keep in touch and even do management decisions remotely, there are times when a face to face meeting is unreplaceable. Whoever feels like a peloton bike is a full replacement of a regular bike has probably never experienced the bliss of a bike ride by the beach in a warm, spring morning.There are moments in the life of a peacebuilder when you literally need to see eye to eye. Feel the energy in the room, let your body speak and listen. There’s simply no virtual replacement for this. The same holds true for any team. There’s simply no replacement for a well facilitated face to face meeting when what’s at stake is the future of the Mission.

Non-violent communication, skillful facilitation of meetings, hosting space for convening, trust building and sharing, are all necessary groundworks for building a solid governance system. The groundwork needs to be in place and ritualized before going into the hard and messy part.

Sense-making, meaning-making, decision-making (SMDm)

What just happened?

If you’re convening a governance meeting, chances are, something happened. Because everyone on the team is so focused on his or her own subsystem, trying to draw a complete picture may be challenging. Typically, we jump too fast to conclusions here. This is where systems thinking comes into play. Every person in the room will contribute with his / her own perspective on the system and so it’s really important to facilitate a sense-making session that casts a wider, systemic lens on the issue. Whatever happened is the result of a system. Whether you’re aware of it or not, it’s 100% guaranteed that there’s an underlying system moving the pieces. The aim of this sense-making session is to flesh out the elements of this system and move to the next phase of the discussion by asking “What does this mean for the Mission?”

For the engineer working on Falcon 9, it’s relatively straightforward to answer this question. It may take some research, modeling and forecasting but it should be possible to figure out what a delay in the delivery of a component means for the whole mission. Remember, it’s just a very complicated clock, not a cloud.

This is not the case for peacebuilding. The meaning of whatever just happened is deeply related to your own individual meaning making structures and how it is shared with the collective. Collective meaning making in social complex systems is impossible to do without some agreement of what reality is. Without this agreement (or “epistemic commons” if you will) how do we know what we know about the social reality and how do we co-create a shared social imaginary? You need to have a shared dream or shared goal to work towards. Without this shared dreamland, collective meaning making becomes impossible.

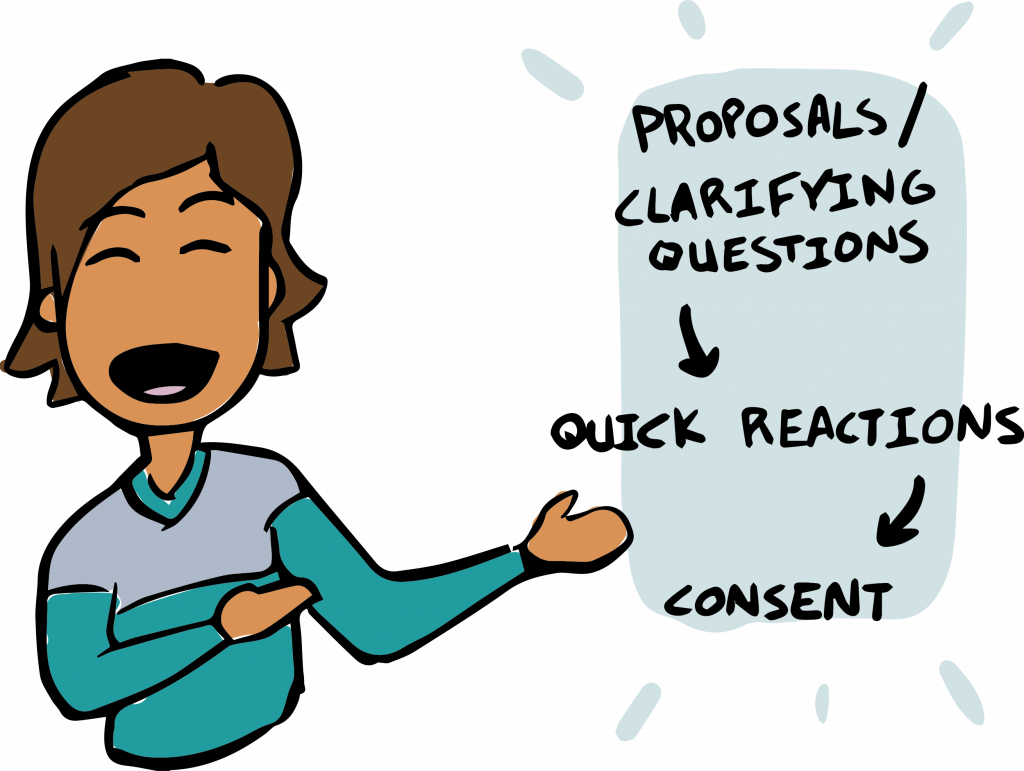

If sense and meaning are shared (easier said than done), proposition crafting and refinement should easily flow out of the previous steps. What?, So What?, Now What? This is the way many Western philanthropies and organizations talk about learning and adapting “and governance” itself is a very Western word with all sorts of unintended connotations. However, this is a universal human concept. Every culture has a way of making decisions. We in the Global North tend to sometimes forget that every day all over the world, people in communities come together to come up with proposals to solve problems. Working in smaller teams or networks could prove to be extremely creative and effective if it is coupled with a decision making process, such as consent decision making to fast track good ideas into actionable prototypes and have a basic foundation for what to do when you do not agree or the plan goes sideways.

Finally, the governance process should answer two cornerstone questions: accountability and legitimacy. Whatever comes out of the process must be accompanied by a clear statement of accountability (who has skin in the game?) and legitimacy. In Western contexts, charters, MoU, constitutions, manuals, contracts, can play a role here. But these can overcomplicate the real work. What I have found in my time in peacebuilding is that the deepening of relationships and agreement for action can start with three questions. What do we want to do together? How will we make decisions? What do we do when we don’t agree? In short, how do we want to show up together? This is one area where I think there’s a lot to innovate in civil society movements. Peacebuilders can learn from movement activists how to set the foundation for adapting quickly while keeping a focus on the desired goal.

Organizing for Peace

Kurt Vonnegut knew it: “There is no reason why good cannot triumph as often as evil. The triumph of anything is a matter of organization. If there are such things as angels, I hope that they are organized along the lines of the Mafia.”

I believe that our perennial mission is to organize. We do that so elegantly with clock problems. Now it’s time to complement that toolset with other rituals that help us organize around cloud problems, too. I hope Pinker’s Better Angels take a lesson or two from the Mafia, but outrage or hope alone won’t cut it. I believe there’s a lot to be done to help peacebuilders around the world get organized in a way which creates, not a rigid, but an emergent order that is able to sense and respond to the challenges posed by the destructive forces of violence and war.

Pedro Portela is the Founder of the Hivemind Institute, a think tank and action research organization in Portugal dedicated exclusively to prototype new models of local organization, advocating for more systems literacy and proposing networked approaches to complex social problems.

Originally published at The HiveMind

featured image found HERE

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

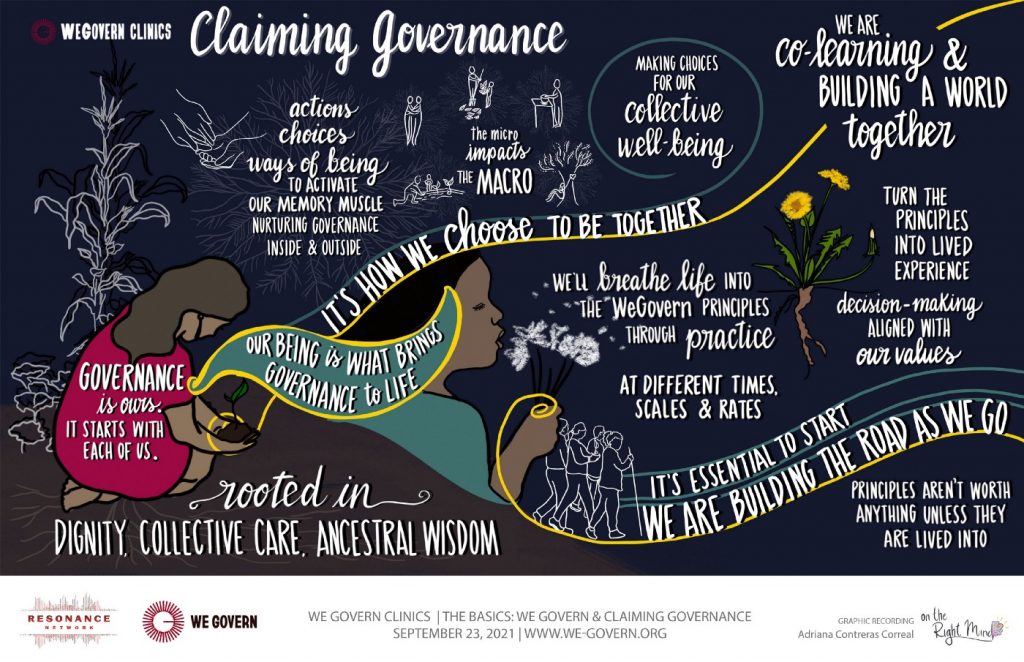

Governance is how we choose to be together

An illustrated story of liberatory governance practice

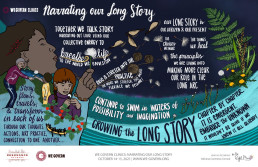

Storytelling — like governance — can take many forms.

When choosing new ways of being together, we begin with ourselves — in our bodies, hearts, spirits. The choice to be in governance rooted in mutual care is an embodied one. Once it rests within us, the practice begins.

Accordingly, the story of governance practice is a multi-sensory one. It takes shape in the colors, textures, voices, sounds, and sensations of our beloved communities — it is multi-dimensional.

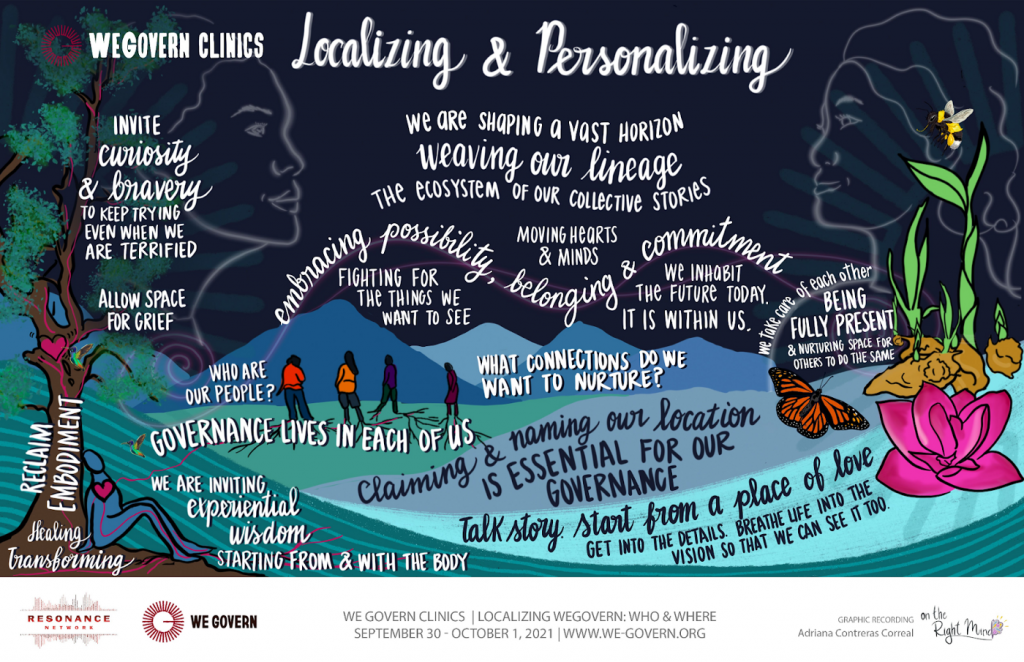

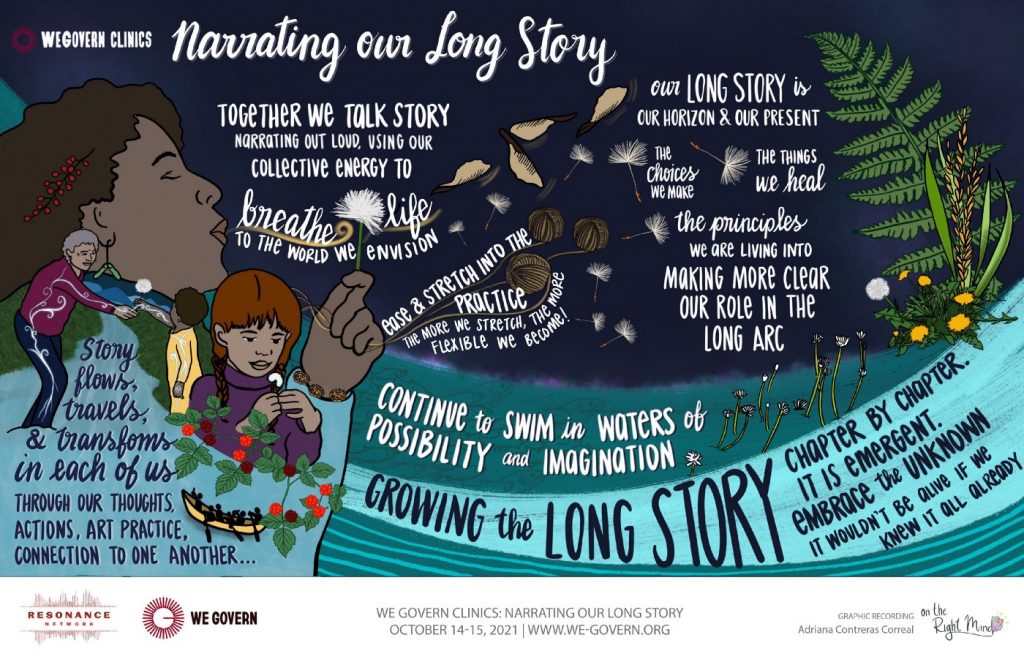

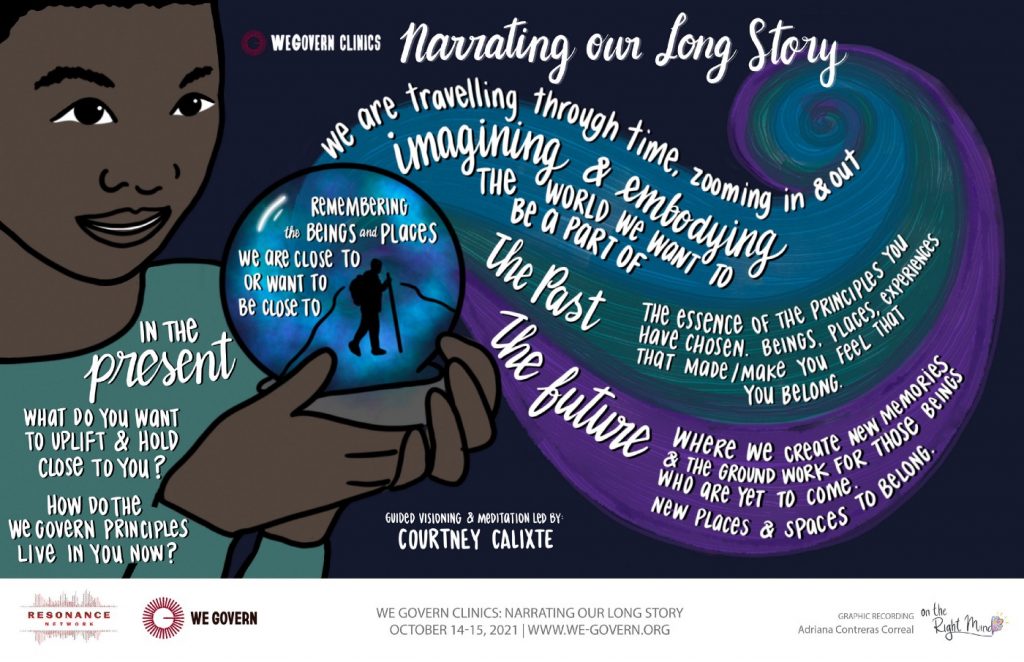

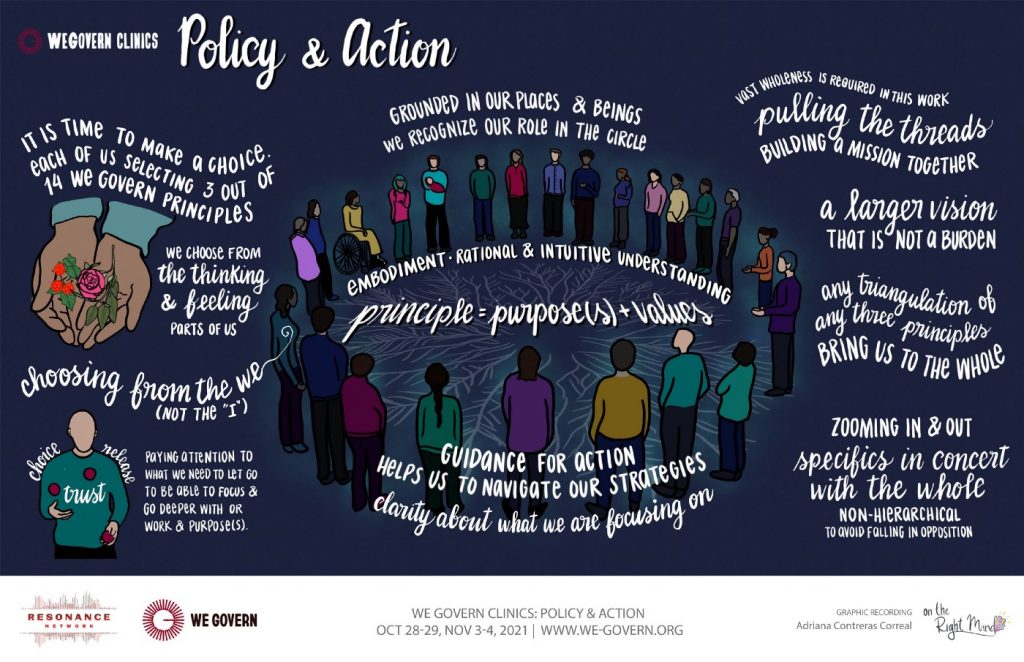

Last year, a group of worldbuilders came together with a shared commitment to collective liberation — and the governance principles we’ll need to bring it into being. Together, we moved through a series of clinics to deepen our collective governance practice.

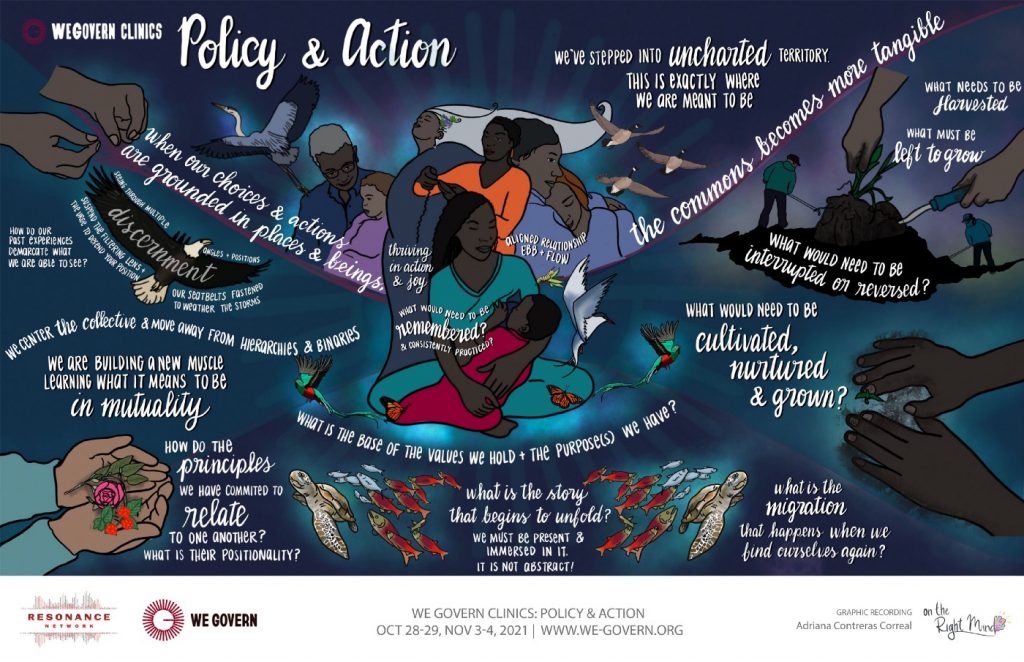

What follows is a constellation of words, images, and musical offerings to describe this journey into liberatory governance. These images are the work of our beloved Adriana Contreras Correal of On the Right Mind. Deep gratitude to Adriana for sharing her gifts with us.

We invite you to enjoy our practice playlist and delve into the story below…

Collective governance begins with a choice: to commit to the ways of being that enable all beings to thrive:

Transformation begins when it’s personal: once we’ve committed to collective governance, we begin by grounding in place. Our work begins at home:

As our practice takes root, we continue illuminating the path toward what is possible, by narrating our visions for our communities into story:

Holding close to our stories of liberatory futures, we focus in on policies and actions we will need to sustain a world beyond violence — a world where all beings can thrive:

Originally published at Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Governance – the overlooked route to transformation: How can we best organise for change?

What are the current governance approaches and ways of organising that are being used in attempts to create systems change? What would more systemic governance approaches for our work look/feel like and how might we transition to these?

Part one in a series of four exploring the future of how we govern and organise. Co-written by Sean Andrew, Louise Armstrong and Anna Birney

“Every attempt to write a new human story converges upon just one mundane, heartbreaking problem: How shall we come together, work together, create together? How shall we organise?”

Nilsson, Paddock and Temmink, 2021, Changing the way we change the world (Draft manuscript)

At the heart of change is how we think, relate and act. While these ways of being weave in and throughout our ordinary everyday experiences, they are not always given the intention and continuous attention they need. We believe how we relate, work together, and organise are cornerstones of change making. How we find ways to bring awareness to these elements really matters, and is easier said than done. They need just as much attention as the structural shifts that are required in the coming decade.

With this in mind, we are exploring governance as the place of untapped potential that can enable transformation today and into the future.

We’re defining governance as: The forms, structures and social processes that people and institutions use to create and shape their collective activities.

As such, we, and many others we’re working with and are inspired by (Beyond the Rules, The Hum, Reinventing Organizations, Going Horizontal, Practical Governance, Organization Unbound, Lankelly Chase, Shared Assets, Patterns for Change, Leadermorphosis and Barefoot Guide Connection, to name a few) are calling for governance approaches that reflect systemic principles that are suited for complex adaptive systems. Many of those we’ve listed are experimenting with elements of this, each adapting these to their contexts like Transition Movement and their shared governance approach, or CIVIC SQUARE, who are applying their mission and values into the organisational structures and processes – from how they do recruitment through to how they do financial planning.

We’re increasingly noticing internally, through our own organisational experience at Forum for the Future, and through our systems change strategy, collaboration and coaching work with others, that many of us subscribe to dominant forms of governance that are designed for a complicated, not complex world. We’ve noticed that sometimes, without intention, our own patterns of organising and those of many of our partners are perpetuating the structures, dynamics and patterns we are trying to shift. For example, we take centralised or hierarchical decision making approaches even though we want to enable greater ownership over a project which can come through taking advice-based decision making approaches where those closest to the challenge are part of the process.

Systemic governance on the other hand enables self-organisation (how a group of people organises their time, attention and resources in ways that meet the urgent necessity of the moment). It cultivates the emergent practices (and enables new system patterns) that help us align to regenerative and distributive approaches that better mimic our living systems.

Our inquiry into governance

After exploring new forms of organising, over the last 18 months at Forum we have been exploring two governance inquiry questions:

- What are the current governance approaches and ways of organising that are being used in attempts to create systems change?

- What would more systemic governance approaches for our work look/feel like and how might we transition to these?

To respond to these questions, we’ve been reflecting on our own organisational life while also learning from current and past collaborations we’ve convened or participated in over the past decade.

What is governance?

So how do people understand governance in their context? Through our inquiry we found that peoples’ understanding and expression of governance varied and was even sometimes quite vague. While governance meant different things to people, depending on their role or context, the people we spoke to talked about it in a few distinct ways, the ‘elements of governance’.

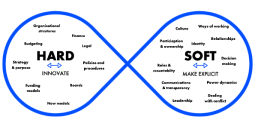

Elements of systemic governance

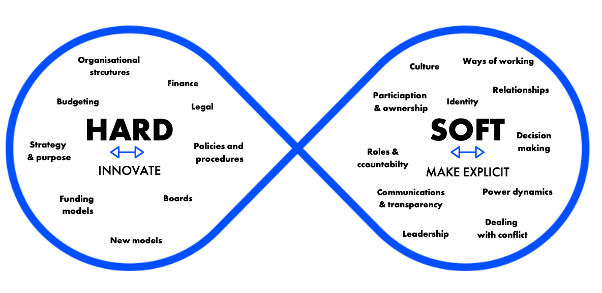

Systemic governance has both soft and hard elements.

Part of the reason why we tend to think of governance as a fixed process is that we often associate it with a few rigid components. From this exploration we realised that governance is in fact made up of a whole spectrum of elements, which while distinct, together create a unique governance context you may find yourself within, be that in an organisation, a movement, a collaborative endeavour, a community or really any place where people come together to organise something. By naming a spectrum of elements it expands the view of what governance is and how these parts form a tapestry.

We’ve created the figure 8 (below) as a summary of what we’ve heard, recognising that one way of distinguishing these elements is looking at the ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ elements. While the hard and soft elements can sometimes feel in tension with each other – they are in fact interdependent and together they form part of the governance landscape we have to traverse together;

In reality – we recognise these elements can be interchangeably hard/soft and are in symbiosis. Some will be visible and explicit and others invisible and implicit, depending on the context and people’s experience. For example, a “hard” element such as finance might actually be very hidden in an organisation without financial transparency or a “soft” element such as communication and transparency might be experienced overtly as lacking and be a visible gap in ways of working.

Innovating the hard and visible elements of governance

Most of the governance approaches we explored focused on the hard and often more visible, explicit structural elements of the organisation. These seemingly felt easier to figure out with clear problem > solution tactics. For these hard, visible structural elements of governance, people talked about inherited “best practices” that often took the form of compliance protocols. When working systemically, challenges can come when the ‘hard’ or ‘visible’ parts of governance are too rigid and fixed. We found that people working on complex challenges were often bound by these constraints and were yearning for ways to disrupt, reimagine, and innovate these ‘hard’ elements.

One hypothesis we are working with is that the hard stuff (the what) can be a transitory tool and a trojan horse for prioritising the soft stuff (the how).

The soft, invisible elements are the hardest part of governance to shift

The “soft” elements of governance are the implicit less formal cultural components of how people relate and organise. It’s often less tangible and thus harder to shift. Systemic governance is a constant practice of probing, sensing and responding to the dynamic nature of these elements in changing contexts. We found that these elements are too often submerged and therefore if we want to develop resilient adaptable governance approaches we need to bring to the surface and made explicit the soft cultural elements. While these elements are often deprioritised as they are unseen, they are still aspects of governance that materially impact the lived experience of people working within different organising forms.

Why is it so hard to work with the softer issues? The nature and quality of our relationships is the foundation of any governance. Questioning, challenging and reconfiguring established relationships is hard. It can take difficult conversations and processes to bring in different perspectives and overcome unhealthy power dynamics. Bringing self-awareness, paying attention to relational dynamics, creating space to listen and honestly share and transparent communications are the starting points.

Reframing governance as a journey

We heard people thinking about governance as putting structures and processes in place and thinking the rest will follow. Any of the words and connotations people mentioned pointed to governance as something that is fixed and hard, a static thing you set up on a one-off basis when in fact governance approaches are alive, can be enabling and need to be seen as a constantly evolving journey. We’ll explore some more of these governance myths in the next blog piece.

Sign up for the newsletter to get the next blog piece directly to your inbox.

Governance as an overlooked intervention or leverage point for change

These elements of governance play out in all of the many ways when we come together – be that in a multi stakeholder collaboration, across teams or functions in a large organisations, in communities, within networks or distributed movements. Governance is central to any form of organising or organisation creating change. We need to support others to imagine and implement new governance approaches that demonstrate and model how we can operate systemically, as a fractal of the change we are cultivating in the world.

What next?

We offer this figure 8 framework as a way to open up a different conversation about governance and acknowledge it is just one framing. We’d love to know if this resonates with your experience and how the challenges of hard and soft elements play out for you?

We’ll be writing two more pieces in this series. One to explore some of the governance myths we’ve been uncovering through our inquiry (e.g. governance helps us control things). And a second to dig deeper into some of the core systemic governance elements you might start to pay attention to now as critical yeast to influence your organisational practices and experience.

In 2021, we’re starting to explore some of these ideas with fellow travellers who have similar experiences in their context. If these ideas resonate with you or you want explore them more – get in touch with Sean s.andrew@forumforthefuture.org or Louise l.armstrong@forumforthefuture.org

Background context

At Forum for the Future, our governance inquiry is one of our three live inquiries (power, governance, regenerative) we’ve been exploring over the last 18months. This inquiry approach supports our aspiration to be a learning organisation that keeps questioning the assumptions nested in our purpose and supporting structures, processes and practices. Our belief is that these inquiries are helping us continuously become a system-changing organisation that is using our own experience as a site of learning, and as an expression of the change work we’re trying to do in the world. This inquiry has been greatly inspired and supported by those in the field who have been, and are, experimenting with ideas and approaches to governance. This piece is part of our ongoing Future of Sustainability series. In 2021 we’re exploring the narratives and practical interventions needed for transformation in the coming decade.

Read next:

- Exploring transformational governance together Governance can be transformational. When we set our sights on changing the world, we also know that governing well goes beyond preparing our own organisation, network or movement for the future. How do move beyond tweaking the way things currently work and apply governance to transform the ‘systems’ that operate in our society that maintain injustice, oppression and inequality (such as race, patriarchy and class)? (PART 2/4)

- Reimagining governance myths Part three in a series of four exploring the future of how we govern and organise. This piece looks at how people think governance happens today and challenge five commonly held governance myths. (PART 3/4)

- The governance flywheel In this final installment of our series on governance, we introduce the “governance flywheel”1 which highlights three fundamental linked areas that if they are deliberately seeded and nurtured, individually and together, can create the momentum needed to cultivate and grow healthy governance systems. (PART 4/4)

Originally published at Forum for the Future

An enabling, empathetic and courageous leader. I questions and challenges the way things are done, models what is possible and enable others to do that too. Sees potential and nurtures it in people and ideas. Living change while knowing how to strike how to strike the balance between adventure, rest, work and care and nurturing.

For another way of thinking about governance alternatives see Resonance Network's post and media toolkit : THIS IS HOW #WEGOVERN

Who Decides Who Decides?

Have you ever started a group that started with enthusiasm and fizzled out over time? I have. Even more often, I have joined groups that other people started… that fizzled out over time.

So, what happened? If your experiences are similar to mine, here are some typical stories.

- Groups start out with a vague understanding of what we’d do together and then we don’t do things because first we talk… and talk about what we would do if we ever actually started. Needless to say, we don’t start but fade away.

- Someone starts doing things. Somehow the doers take over and there’s no room to plug in. We’re all grateful but there’s also no room to talk about whether what they’re doing fits with the rest.

Self-organization is powerful because it has the potential to align a lot of people and their passion with each other. Yet, self-organization doesn’t mean having “no rules”.

The invisible force that makes or breaks a new group is governance. Governance doesn’t sound exciting, and it reminds everyone of boring board room meetings. Yet, the truth is that governance is everywhere - every group that makes decisions gets to those decisions somehow - whether we like that way of making decisions or not.

So how can we introduce just enough clarity and process to make governance inclusive, easy and unleash the power of self-organization? There’s a new book that describes exactly that. It uses the tools from sociocracy - a consent-based, heavily participatory, and co-creative decentralized governance system - and lays out how to start a group and put decision-making and a good distribution of responsibility and actions into place step by step. The book has printable meeting templates of the first 3 meetings that will support your new group and launch it well!

- In the first meeting, a group establishes how they operate and what they do. They celebrate being a group and spend time getting to know each other.

- In meeting #2, a little bit of structure is established so everyone knows how to contribute, and the group can plan for the future in an accountable way.

- Meeting #3 is all about getting started and reviewing what we’ve done so far - only if we review our processes can we make sure everyone’s needs are considered and we are intentional about how we spend our time.

The process works the best for groups of 3-12 people who are actively involved. It can be used to start or to re-kindle a group.

The book comes with a resource page of printables, demo videos and an interactive forum.

Ted Rau is a trainer, consultant and co-founder of the non-profit movement support organization Sociocracy For All.

He grew up in suburban Germany and studied linguistics, literature and history in Tübingen before earning his PhD in linguistics there in 2010. As part of that career, he moved to the USA and fulfilled a long-held wish to live in an intentional community. Since a career in Academia required more moving around than he was willing to do, he left Academia. Ted identifies as a transgender man, and he is a parent of 5 children. He lives with 70 neighbors in Massachusetts in an intentional community. Link to more info on sociocracy

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.