EXPLORING THE COLLABORATION CYCLE

Below is an excerpt from the full article which can be downloaded here or at the bottom of this post. This article a part of the Tamarack Institutes Collaborative Governance and Leadership series.

The Collaborative Context

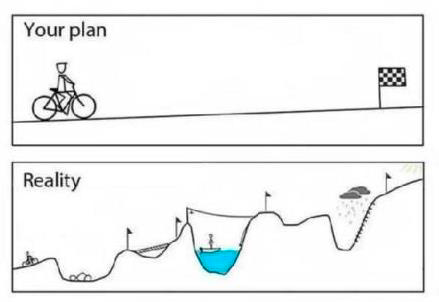

Many enter into collaboration thinking that the shared work is a linear and flat process from start to end. One of the favourite images describing collaboration that is often included in Tamarack power points is this image of plan versus reality. It captures the reality of collaboration including the twists and turns that collaborative efforts face as they move from start to completion. It can include obstructions like boulders and choppy waters and other challenges which are found obstructing the path along the way. This image always receives a small chuckle because individuals in the room have experienced these challenges.

However, the reality image still conveys a relatively linear, if upward, and challenging experience. This image is relevant for collaborative efforts seeking to achieve a result that is more defined such as the exchange of ideas, or development of a new program or service.

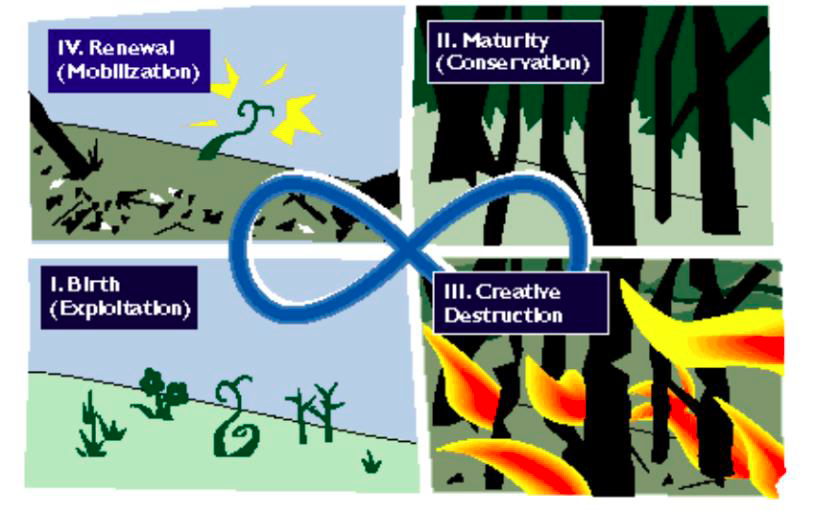

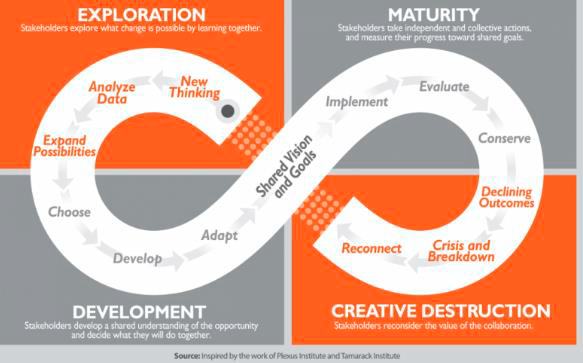

For more significant community change efforts, a different approach was introduced to Tamarack by Brenda Zimmerman of The Plexus Institute. Zimmerman described community change as a more cyclical process mirroring phases of development found in ecology.

The ecocycle concept is used in biology and depicted as an infinity loop. In this case, the S curve of the business school life cycle model is complemented by a reverse S curve. It is the reverse S curve, shown below with the dotted line, that represents the death and conception of living systems. In our depiction of the model, we call these stages creative destruction and renewal. The importance of the infinity loop is that it shows there is no beginning or end. The stages are all connected to each other. Hence renewal and destruction are part of an ongoing process.

Being an infinity cycle, there is no obvious start or end to the cycle. Let us begin our examination of the stages at the beginning of the traditional S curve. We will begin each phase by using the biological example of a forest and then look at the analogous phase in human organizations.(i)

The four phases of the ecocycle, as described by Zimmerman and the Plexus Institute follow the traditional (and linear) growth curve from birth to maturity. However, it also considers a renewal loop. The renewal loop includes a creative destruction phase and a renewal phase.

The image from the Plexus Institute website displays and describes the ecological cycle of a forest which starts with a variety of different plant growth (birth) which leads to increasing density as the forest grows to maturity. At maturity, the forest becomes increasingly vulnerable because of the density of growth. It can experience rot through invasive moths or pests or be ruined because of a forest fire. The creative destruction phase creates the space for renewal and regrowth. It is often the results of decay that enable the regrowth or renewal to seed.

Using the Ecocycle to Inform Our Practice

The ecocycle has been adapted by many organizations over the last several years to describe a better way of understanding community change and collaboration cycles. Tamarack has used the ecocycle to inform our practice of supporting communities tackling complex issues like ending poverty, building youth futures, deepening community, and navigating climate transitions. Tamarack, influenced in our early years by Brenda Zimmerman, recognizes that communities are dynamic and responsive. Even as collaborative tables begin to intervene in community change efforts, the community begins to respond, grow, and change. The ecocycle approach can be useful to collaborative tables to help understand and navigate dynamic change recognizing that change is not linear but rather exists in phases and cycles.

From Ecocycle to Collaboration Cycle

There have been many articles written about the Ecocycle and adaptations to this approach. One useful adaptation of the ecocycle was developed by Chris Thompson, Collaboration – A Handbook from the Fund for our Economic Future. (ii) In this handbook, Thompson adapts the ecocycle to a collaboration cycle approach. Thompson builds of the Plexus Institute ecocycle framework and Tamarack’s approach to adapting the ecocycle to community change efforts. Thompson uses the phases language of development, maturity, creative destruction, and exploration.

Thompson describes three elements which are vital to impactful collaboration: capacity, process, and leadership. The collaboration cycle is useful to focus on the process of collaboration.

This cycle serves as a roadmap for the diverse players who are along for the collaboration journey. It is invaluable to new participants joining an existing collaboration, as it can be used to help them understand where the partners are on the journey. Advocates of collaborations, particularly those performing the key collaboration functions, also should take the time to help each partner assess where they are on the cycle. Not every partner travels through the cycle at the same pace. (Thompson. Page 29) Thompson provides useful steps in each of the phases such as developing new thinking, analyzing data, and expanding possibilities in the exploration phase

In the development phase, the steps include choosing strategies, developing approaches, and adapting as the collaboration moves forward. The maturity phase includes implementation, evaluation and in some cases conserving to build on successful results. The creative destruction phase is initiated by declining outcomes, crisis, or breakdown and reconnecting.

Access the full article HERE

Liz Weaver is the Co-CEO of Tamarack Institute and leading the Tamarack Learning Centre. The Tamarack Learning Centre advances community change efforts by focusing on five strategic areas including collective impact, collaborative leadership, community engagement, community innovation and evaluating community impact. Liz is well-known for her thought leadership on collective impact and is the author of several popular and academic papers on the topic. She is a co-catalyst partner with the Collective Impact Forum.

Liz is passionate about the power and potential of communities getting to impact on complex issues. Prior to her current role at Tamarack, Liz led the Vibrant Communities Canada team assisting place-based collaborative tables to move their work from idea to impact.

featured image found here

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

Moving from ladders of engagement to self-organizing as decentralized leadership

Thanks to June Holley for thought partnership!

In campaign-based organizing, we tend to think of engaging people hierarchically: the goal is to move people up the ladder, progressively increasing their levels of engagement. Transplanting this to network organizing can give people a sense of “the network does all the things for network members,” where a few network facilitators become responsible for creating all engagement activities.

These practices shouldn’t be applied to networks. Why? Network members often experience shifts in capacity to engage in a way that is non-hierarchical. Because network participation often happens outside of the context of a job: we may devote less time to it – more sporadically and perhaps with varying levels of commitment. Network organizers should embrace these factors as part of how networks work, rather than trying to mash organizational thinking into network structures.

So, I’m starting to understand the idea of self-organizing as a decentralized, non-hierarchical version of engagement and leadership. We need to unlock this decentralization and move away from centralized levels of engagement. I say unlock because I think this involves a process of unlearning: doing things differently and practicing new ways of being with each other.

Attributes of a network that support self-organizing

- Widespread desire and openness to collaborate: it feels easy to meet people who are interested in talking, sharing learning, open to new ideas

- Self-authorization: you don’t feel like you have to ask for permission

- Accessible resources: including funds, spaces for discussion, knowledge databases, mentors or coaches, whatever else

- Liberatory culture: all network members actively practice undoing oppressions; working across privileges

- Spaces to learn in: you can see what others are doing, you feel like you can ask questions and get answers; you can see what others are learning

- Culture of seeing “failures” as rich learning opportunities: plus a shift away from an attitude of seeing these projects as a waste of time/resources

- Understanding: how individual’s efforts connect to network goals/values/principles

- Connecting the dots: ease of finding the right people to collaborate with and learn from

What prevents network members from self-organizing?

- Not feeling autonomy: having experienced generations of marginalization, disinvestment, and maybe never having seen someone like them in positions of power

- A narrow definition of leadership: privileging only a very specific type of person and way of interacting to be able to arrive to a position of power. This relationship to leadership trains us to do what we’re told rather than to initiate

- Resource dams and gatekeeping: only certain people have easy access to resources and/or resources are accessible but only after jumping through flaming hoops

- Lacking a sense of belonging to the network: why should I contribute? What’s in it for me?

- Culture: how we understand all of these things (autonomy, leadership, resources) is artificially narrow – we’ve become trained to understand them in certain ways and may have difficulty imagining that they could be different

How do we unlock decentralized engagement?

- Popular education: training and capacity building for and from within marginalized groups (these can be groups that are literally on the margins of a network, and/or groups of people that have been pushed to the margins of dominant society)

- Less gatekeeping of funds: innovation funds and shared gifting can be a way for funders and other gatekeepers to begin to practice letting go of control. Decolonial commons and cooperatives are closer to real, community control of resources. (Consider also: reparations!)

- Communities of practice: to unlearn some ways of being and practice new ones – creating new cultures of interacting: specifically anti-racist, feminist, decolonial, and otherwise undoing hierarchies. Pair that with being caring and holding space for change and cultural shifts.

- Protocols and practices: break down how to do things – the steps to take to form a project – as an activity that regularly happens in a network

- Naming power: measuring and creating intentional interventions around demographic shifts for who is/remains are in positions of power in a network will help xyz

- Logging Data: collecting, sharing, and visualizing data that gives us a real-time picture of where we are in this shift

Finding best fit: using network weaving to help people find the “right” person/people to start a project with

About Ari Sahagún

I grew up in the tallgrass prairies of Illinois, where the lanky sandhill cranes pause on their way to and from Mexico. Retracing one of my family’s roots, I’ve recently moved south to Mexico City to do what I do as a mixed heritage person: build bridges. One facet of my work is building bridges between extractive capitalism/colonialism and a society that repairs and regenerates from these traumas. I’ve run praxis groups on decolonization and helped investors move hundreds of thousands of dollars to Black- and indigenous-led projects in the US and internationally. The other part of my work is building bridges that support movement networks on the path toward a more just society. Right now, this looks like facilitating peer learning among climate justice organizations in the United States, mapping interconnections that support power-building in California, and co-designing a complex, emerging network to support health equity. My specialties are at the intersections of justice, co-design, network strategy, social network analysis, technology, and communication cultures.

featured image found HERE

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

What is Network Weaving? - Q & A with June Holley

June Holley is a Wellbeing Blueprint signer who has been weaving networks, helping others weave networks and writing about networks for over 40 years. We recently sat down with June to define network weaving and help us understand how it can be a game changer in building our collective capacity to bring about social change.

Q: What is network weaving?

A: Network weaving is something that we all do. It’s paying attention to the relationships around you and noticing who’s missing, who’s not being listened to, and helping create healthier, deeper relationships. You do this by bringing new people in, by connecting people within your existing networks, and helping them get to know each other so they can work together.

Q: What is the difference between networking and network weaving?

A: When people think of networking, they think of passing out business cards to people at a conference and selling themselves. So networking is all about yourself. But when you move to network weaving, it’s about the community. It’s about the people around you and helping them build a network that can be capable of support and action. It’s a pretty different thing.

Q: What does network weaving have to do with building a country where everyone has a fair shot at wellbeing?

A: The concept of wellbeing is really complex and there are a lot of pieces to it. It might be about health access, it might be about creating a safe community. But before people can begin to work and co-create these kinds of things in their community, they need to know each other deeply. They need to be able to trust each other so they can work together. Working on the network and relationships is about creating the foundation, the fertile ground, on which aspects of wellbeing can emerge. So the more time you invest in building relationships, the easier it will be to work together on wellbeing.

Q: What’s one thing someone can do to start network weaving?

A: One of my favorites that you can do at every meeting you have is called speed networking. It’s a way to help people either get to know people that don’t know each other, or help to deepen relationships.

It goes like this: you ask people to stand up and find somebody they don’t know or don’t know well. And then you give them a juicy question like, “What’s keeping you up at night?” Or “What’s something about yourself that not many people know?” And you give them about five minutes to talk back and forth. Then you have the group come back together to debrief. You can ask them what made their partner a good listener. People will list things like eye contact, nodding, asking good questions, feeling really heard, etc.

Now that the group has established some guidelines for good listening, you ask everyone to pay attention to their listening skills in the second round. Then you give them another question, they go off and talk to somebody different this time. After the group reconvenes, everyone can share out the difference they noticed during this round. Often people will say they noticed themselves being a better listener and getting more out of the conversation.

There are lots of very easy, small things that you can do to interact with people in new ways that are much healthier and lead to much more effective and interesting actions.

Learn More

- For tools, resources and events, visit dev.networkweaver.com.

- For an introduction to June’s thinking around network weaving, check out her collection of posts on Medium.

- To ask questions and connect with a community, join the Network Weaving Facebook group.

You can also download a pdf with a link to this interview to save to your personal library by visiting the Network Weaver Resource Page.

Originally published at Wellbeing Blueprint

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Reclaiming Care Beyond Roe v. Wade

When the state cannot guarantee our safety, we turn to community as our ancestors did

On June 24, Roe v. Wade was overturned by the Supreme Court after nearly 50 years as precedent.

Weeks before, in response to the leaked decision, Resonance Network hosted ‘We Are Our Own Medicine,’ a gathering grounded in community, storytelling, and ancestral wisdom. Alongside Black and Indigenous healers of various traditions, we came together knowing what our ancestors have known for generations: the state cannot guarantee our safety — it never has.

In the US, incarcerated, disabled, undocumented, poor, queer and trans folks, and survivors have been denied reproductive rights, bodily autonomy, and care for decades. Because this violence lives in our history — and shared reality — we gathered to learn from and share stories from ancestors — past and present — who’ve lived this experience.

In short, when the state cannot guarantee our safety, we turn to community as our ancestors did.

Below is a constellation of wisdom from ‘We Are Our Own Medicine.’

* * *

Deoné Newell — Women’s Empowerment Coach

Deoné is a Navajo/Black entrepreneur, Breathwork Facilitator and Women’s Life Coach. As a woman who hails from the Navajo Reservation (Window Rock, AZ), and has seen the effects of systemic oppression and generational trauma firsthand, Deoné has dedicated herself to making ancestral healing, and its forgotten wisdom accessible to as many BIPOC women as possible.

Karen Culpepper—Clinical Herbalist/Educator

Karen has been a practitioner and bodyworker for over 14 years, focusing her work on intergenerational trauma and its impact on physiology and womb restoration. Her study of cotton root bark as an abortifacient and source of sovereignty for descendants of captured Africans in the US and beyond offers insight into the role of plant spirit healing in the context of political changes.

Qiddist Ashé—Founder, The Womb Room

Qiddist is a medicine woman and female health educator. Informed by her maternal lineage of Ethiopian midwives and her own work in authentic midwifery, functional health, herbalism, somatics, and spiritual sovereignty, Qiddist merges the science and the spirit of female health, orienting to all the ways we can reclaim agency and responsibility for our bodies and our lives.

Camila Barrera Salcedo—Doula/Midwife/Educator

Camila is a mother of 3, doula, midwife, sexuality therapist, and holotropic breathing and fertility therapist. She delves into the unconscious via the physical body to identify blocks that disrupt the evolution and transformation of individuals. She develops workshops to re-establish the feminine consciousness through acceptance and knowledge about the body and its processes.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Reclaiming Choice and Agency in a Networked World

Welcome! We are happy you chose to open this blog post! In this article we will explore:

- The difference between choice and decision; and why awareness of choice matters - as a (fundamental) way to engage with life.

- Different levels of networks & systems and how to navigate the levels with agency.

- How to choose with your whole being - as a means to align your deeper values and actions.

- Exercises and prompts to practice choice as a capacity.

We believe that it can be of use to change agents, social innovators, system entrepreneurs, and curious minds. Most importantly: We invite you to choose to fully engage with the article and share your reflections with us. We have laid out some opportunities to do so on the way :)

So let’s dive right in!

Choosing to Decide

Each day we make numerous decisions, from what we consume, such as food and media, to how we respond to others and to our environments, and beneath all of these decisions are choices. Yet, what is the difference between a choice and a decision? A decision often implies reaching a conclusion you can act upon, in this process something is determined. While a choice implies an act of choosing between two or more possibilities. In this way, ‘choosing’ is a practice of continually aligning toward various decisions. If we zoom out we may see that choices are how we navigate through life and how we arrive at decisions. Let’s take a moment to ponder this.

What was the most important decision you made today?

And what was the underlying choice you made that led you to that decision?

Choosing and deciding are related processes, yes, but they are fundamentally different in their nature. Choosing is relational, it is a process of orienting ourselves towards something of importance, such as our personal values, and what we hold dear. Choices lay out possible paths and open up fields of opportunities. While, deciding is directional; decisions are the concrete steps we take on that path.

If we shift from considering the individual level of choice to the collective level, we can see that human actions are a dominant driving force for what’s happening, and going to happen, on this planet. From this perspective our actions may look insignificant at a larger scale.

But an easily overlooked perspective is that we are not passive consumers or bystanders in the course of history. There is choice and agency everywhere, in the seemingly small moments of our daily lives, in the conversations we have with loved ones, or in choosing, or changing, our careers. Each moment holds an underlying choice we can engage if we choose to.

Now, a common argument is that the challenges we are facing are so grand and complex - that it doesn’t really matter what I intend, do or think.

In this article we will flip this argument around: In a networked world, there is nothing that matters more than what you do. Not only for you and your immediate environment, but also for the world at large. What you do, in turn, is deeply embedded in the choices you make, as your choices shape your orientation toward life.

Engaging with choice can also foster your sense of agency. Agency refers to the ability to direct your own actions in a meaningful way. In the field of systems impact, agency is often the precursor to creating change within our immediate environment or the larger social context we exist within and care about. As we reclaim our sense of choice, we inhabit more of our agency, which in turn enables us to have a greater impact.

Before we unpack this more and dive deeper into the exploration on how to reclaim choice and agency, we invite you to do a little exercise with us, to connect with what supports your sense of choice and agency.

You can follow the steps below or use this mentimeter survey for guidance: https://www.menti.com/txm61jx7f7

(if you use the survey, we will anonymously keep track of the responses - and you can also read through the results of others for inspiration)

- Think of a current situation that frustrates you - where you feel you don’t have choice or agency. This can be something in your immediate environment - or a larger social issue. How would you describe that situation? What emotions are present for you? What is the root cause of your frustration?

- Now, think of a moment in the past where you felt similar, but then experienced some sort of breakthrough - a moment where new opportunities emerged. Enter that moment now. Take a few deep breaths and observe what shows up for you - in terms of images, emotions or intuitions.

- Now consider, what made that breakthrough, that shift, possible? Note down a few words, lines or images.

We will return to this exercise at a later stage in this article.

Agency in a Networked World

We all exist in webs of relationships, which are the most basic form of networks. Networks exist within and around us. In nature we see networks of mycelium, mushrooms and fungi; the internet is a network of networks consisting of computers, routers and webpages. If we consider our bodies we can see that even our brain is made up of neural networks and synapses. Networks show us that it is important to focus on the individual elements as well as the relationships between them.

In essence, referring to our world as “networked” mainly means four things:

(1) We are part of more networks than ever before. Just count the number of initiatives, groups and organisations you are connected to - and compare it to the generation before you.

(2) the networks we are part of are larger in scope than they have ever been. Technology, mainly the internet, has made it possible to decouple social connections from physical proximity, at least to a certain degree.

(3) The networks themselves are connected. what happens within one network impacts others, for example a traffic jam or delayed trains in a transport system can lead to people being late to work.

(4) The networks we are part of, or deliberately not part of, shape our identity and actions. In turn, we also shape the identity and possible actions of these networks, yet usually to a lesser degree.

Let’s explore one aspect further: having agency within a networked world. To distill things a bit, we can say that there are three major levels of networks. For simplicity's sake, moving forward, we will use the terms “network” and “system” interchangeably.

- Individuals: Human beings in their full complexity and wholeness

- Intermediary institutions: Systems we can belong to and that we can shape, e.g. a family, sports club, impact network, or organisation.

- Societal systems / institutions: governments, the financial sector, etc.

Now, there are connections within each system, e.g. between coworkers of an organisation; between systems of the same level, e.g. organisations within an alliance; and between systems of different levels, e.g. an activist group trying to influence a policy.

We each will have varying degrees of agency in relation to the three levels of networks mentioned above. For example, personally fighting financial injustice, individual level, by ignoring letters from the financial department, societal level, is not the most promising strategy. As individuals, we usually have very little leverage over societal institutions and matters. However, joining an organisation, an intermediary institution, that creates financial literacy among disadvantaged groups and lobbies for policy changes, might actually work.

With an awareness of each level it becomes easier to choose which level and interaction you say yes to and no to. Choices are an opportunity to lean in and engage with the networks within and around us. Yet we may often jump to decisions without being aware of the choices that are available to us. This awareness, from our perspective, is the first step towards reclaiming choice and agency.

Choice for Impact

In engaging choice for creating systemic impact, a key question is: What’s the issue or vision I want to contribute to? To achieve that, what is the relevant system that I want to change, and in which direction do I want to change it? Let’s apply what we’ve learned so far, by drawing on the concepts of choice and agency as well as the three levels of systems. To make this more tanglible, you can bring to mind the situation that frustrates you from the initial exercise, and take a moment to think about the societal issues that underlies it.

To move from inertia to agency, we see four levels of choice.

The first choice is about living into your values and allowing yourself to take your inner compass and drive for social change seriously. This can be in relation to a social issue or external “trigger”, such as observing environmental destruction or diversity loss in your area.

The second choice is to think systemically and be strategic, asking the question: what is the relevant societal system I can engage with in relation to this topic? This choice is context dependent and will vary depending on where you live, the resources you have access to, and which systems may be standing in the way of it becoming a reality. For example, there may be a larger societal system that needs to be shifted, such as the energy supply system with its given sources of energy and the extraction of these resources.

The third choice is to engage my agency and seek intermediary institutions to engage in. It’s a choice to be proactive about changing the status quo with an attitude of both realism, “we should do something or else..”, and optimism, “there is something I / we can do”. Taking the example of climate justice, this might result in joining an energy coop or an activist group to influence politics.

Lastly, the fourth choice is to remember the choices above and embody them with joy and a sense of optimism. We can only be effective change agents if, to paraphrase Gandhi, “our lives are our message”.

Our modern day and age provide us with the unique opportunity to use network effects on a global level to contribute to causes we care about. The Four Levels of Choice can serve as a general orientation, acknowledging that it’s rather circular and interdependent than linear in its application.

Another way we can understand the levels of choice is through imagining an iceberg. Part of the iceberg is above water yet the majority of the iceberg exists beneath the water's surface. The part below the surface represents our values, beliefs and mental models, while the part above the surface represents our behavior and actions. Choice is how we align what is beneath the surface, with what is above the surface, therefore aligning our values with our behavior and actions.

We invite you to go back to your personal situation and example, either for yourself or in the mentimeter survey: How can you relate differently to move from frustration to agency? What are the underlying choices you have?

To give the topic more depth, there are two additional perspectives we’d like to explore, starting with ourselves and the choices we have within.

Choices within

Choice is in essence a process of alignment. At the deepest level choice can be seen as aligning with life, both in a general sense and in the present moment. Through choice we can also engage the intelligence of our body, our senses, organs and our imagination, in noticing what arises in response to a particular direction. Upon waking up in the morning, you can ask yourself ‘what am I choosing today?’ and then notice what arises, not only in the realm of thought, but also through sensations, images, textures, sounds and other experiences. Over time, by cultivating an awareness of how we respond to a given direction, we become able to choose more fully from our whole being and find greater alignment in our subsequent decisions.

At one level these choices within are momentary. They can arise through what we give our attention to, how much we open ourselves to experience something, and how much context to bring in and share with another. Choices can also span time and serve as a north star. For example, choice can manifest through a sense of calling, something we choose again and again that moves us closer to a dream we have for the world. As such, choice becomes the fuel for moving forward. Choice in that sense is an ongoing journey. As we pursue our calling we can reflect on the values we are choosing to enact and the principles we are choosing to embody in service of those values.

Here are some guiding questions to work with choice as an ongoing journey and a calling:

- What is so dear to you that you are willing to choose it over and over again?

- What is choosing you? What are themes you repeatedly run into?

As stated earlier on, our choices reveal our basic attitudes, beliefs and feelings toward life.

Choices underlie our decisions; they move us from thought into action.

Choices in Impact Networks

Yet there is still another dimension of choice, namely within networks or intermediary institutions. We can see these choices through the levels we outlined above as well as in any context where we exist in relation to other beings. An example of this kind of intermediary institution is an impact network, a network that is intentionally created...

Here we can see that there are two fundamental dynamics at play.

In the first dimension such a network coordinates and synergizes individual actions around shared principles and a collective purpose that individuals have chosen to participate in. The purpose of the network may not mirror the individuals’ purpose, however there is usually a synergy between the individuals’ purpose and the purpose of the network.

In the second dimension, impact networks support and carry out collaborative action and learning for deliberative change on social and environmental issues.

Choice shows up in each of the two dimensions within an impact network:

Dimension 1 is about choosing how to create the best possible conditions to engage network members. This requires the network to provide incentives to individuals to actively engage, and at the same time recognise the overall purpose and strategy of the network. For example, establishing rules around membership and criteria for internal decision making.

Dimension 2 is about choosing how to relate proactively to the societal issue and its related system(s). Impact networks, therefore, are an ideal testing ground to practise agency and choice in an intentional way.

Practicing Choice

We’ve seen that the decisions we make are often preceded by an underlying choice we’ve made at a conscious or subconscious level. When we connect with the dimensions of choice we can connect with a greater sense of agency in our immediate context and within the larger systems we are a part of. This awareness, in turn, supports us to become more intentional and impactful in the decisions we make and actions we take.

Choosing is also a capacity that we can cultivate through practice. Throughout each day we can notice the choices available to us and choose to engage our choices consciously. Awareness is the first step. We can practice recognizing the choices we have in the moment as well as the different dimensions that we can engage our choice in. Choosing deliberately increases our agency - the ability to direct our own actions in a meaningful way.

Choices help us to orient ourselves towards the world we wish to create- with all its complex challenges.

It’s a practice, like building a muscle or learning a new skill.

With this article we hope to provide an accessible framework to rethink and reclaim choice & agency, to invite each of us to begin to practice engaging the choices we have, from the large, to the seemingly mundane or small.

The following worksheets are designed to support you in that practice:

- Choosing for impact (4 steps)

- Choosing with my whole being

- Choosing and being chosen: exploring our north star

Download all 3 worksheets in one package HERE

Happy choosing! All worksheets are under a creative commons license, so feel encouraged to invite friends, colleagues and whoever comes to mind into the practice.

About Elsa & Jannik - the authors

This article is a co-creation in the truest sense. We noticed early on in our explorative conversations that we share interests and perspectives on many topics, such as impact networks, creating and evaluating systemic change, and capacity development. We also recognised our complementary backgrounds.

Elsa Henderson is a practitioner at the Converge Network and faculty at the Metavision Institute. She moves between the roles of network consultant, facilitator and educator supporting individuals and groups to deepen their capacity to collaborate for systems impact and find meaning even in the midst of uncertainty. Her background is in process-oriented psychology and anthropology, with an interest in phenomenology, systems thinking and consciousness studies.

Jannik Kaiser is co-founder of Unity Effect, where he leads the area of Systemic Impact Evaluation, grounded in the knowledge that evaluation can be participatory, meaningful and energising. His background is in sociology, with a continuous passion for complexity science, phenomenology and asking fundamental big questions about life.

In our conversations, we also allowed our minds to wander and our intuition to speak. In the end, it felt more like the topic of choice ‘chose’ us. And we could feel the depth and richness in it that is calling for further explorations.

To give one example: The image of the iceberg and choice as a process to align our values and principles and translate them into action. This aligns with the three levels of reality process-oriented psychology, namely (1) consensus reality, (2) Dreamland (inner worlds & imaginations) and the (3) Essence level (the non-dual pre-manifest field of ‘implicate order' as coined by Bohm. It also fits with Ken Wilber’s AQAL model, according to which each system has an interior (invisible) and exterior (visible) dimension.

An interesting exploration could be how individual and collective choices are connected. The iceberg is swimming in a vast ocean of water. Similarly, our individual choices are embedded in what we could call consensus reality or culture. Yet this consensus reality is currently being questioned, and the topic of choice could inform how we transition between such collective realities.

So stay tuned, there might be more coming up.

originally published at Unity Effect

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

From Learning to Doing

Many years ago I was teaching high school English on a small island in SE Alaska. I asked the class to compare a piece of literature to the story of the Three Little Pigs. Half of the class couldn't do the assignment because they had never heard of the story of the Three Little Pigs. That changed me forever.

Without shared experiences, learning communities often talk past each other. Inevitably there is a judgement on one side or the other. Each learner brings his/her own experiences to a conversation and uses those unique experiences to make sense of things. Coming together as a learning community to sort through what we understood from something new that is introduced to us is sometimes very frustrating because of all the different experiences brought to the table. To help with that issue in almost any learning community, you can initiate a common experience/action for all participants. When an action is experienced together, suddenly there is more justice in the conversation. The playing field is leveled and the real conversation can begin.

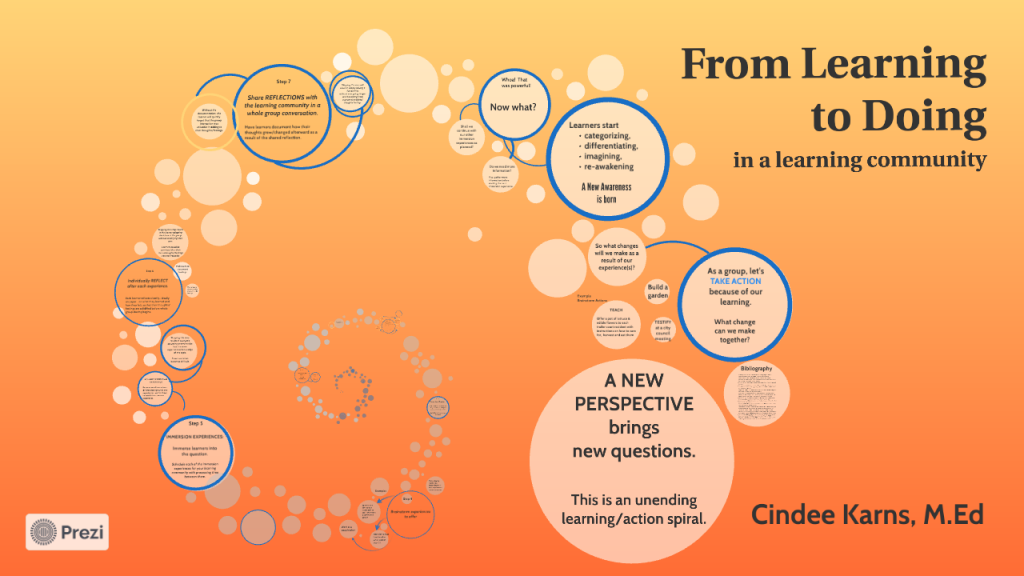

This is a depiction of how that process can be set up for any learning community. The condition is that the learning spiral never ends....every round goes higher, higher. The outcome is that participants almost always feel like they can act on their new knowledge and continue the learning cycle on their own.

Click HERE to access the "From Learning to Doing" resource. A slide presentation on how to create shared experience in a community to initiate actionable change.

Click HERE to access the slide show directly at prezi.com

Cindee Karns, a life-long Alaskan, is a retired middle school teacher with a master's in Experiential Learning. She is founder/weaver of the Anchor Gardens Network, which is attempting to bring increased food security to Anchorage. She and her husband live in and steward Alaska's only Bioshelter

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

The Art of Measuring Change

What are your associations with words such as “measurement”, “evaluation” or “indicator”? For many people these words sound annoying at best, and there are good reasons for it. Yet - given the fact that you clicked on this article - it’s also very likely that you are motivated to contribute to social change, and the main intention of this article is to share about the beauty and collaborative power of attempting to measure it. What I am not doing is offering quick solutions, the same way art is not a solution to a problem. Rather, it is an invitation to step back, look at the nuanced process of change with curiosity and an inquisitive mind, and maybe discover something new. The article is also available as a dynamical systems map.

In a nutshell

There are two ways of reading this article:

- Exploration mode: Use the systems map provided above and use the visual representation to navigate through the article more flexibly.

- Focussed mode: Stay here and follow the flow of the article.

Here already a quick overview of the main points and arguments:

- There is a good reason to be skeptical of impact measurement. If the approach taken is too simplistic and/or mainly serves to validate a perspective (e.g. of the donor), it’s almost impossible to measure what truly matters. Rather, such an approach further perpetuates existing power imbalances and puts beneficiaries at risk. (section: The dangers of linearity)

- The measurement of social phenomena has to pay justice to the intricacies and complexities of a project, a program, or any given action. This requires understanding, which puts empathy, listening and collaboration at the centre of an empowering approach to measuring change. (section: About potluck dinners and “power with”)

- Meaningful indicators serve as building blocks in the attempt to capture social change. An indicator is meaningful when it not only follows the SMART principles, but is also systemic and relevant, shared (understood and supported by all stakeholders) and inclusive (aware of power relationships). (section: Indicators that matter)

- Complexity science can provide an alternative scientific paradigm to understand and make sense of our world and, hence, to measure change. (section: Coming back to complexity)

- It’s time to equally distribute power, namely the ability to influence and shape “the rules of the game”, or potentially even the kind of game that is being played in the first place. A crucial step towards this is describing and defining what desired social change is and how we go about measuring it in a collaborative way. (section: Synthesis)

The starting point

I have been working in the field of impact evaluation and measuring social change for around 6 years now. I’ve interviewed cocoa farmers in Ghana, developed surveys and frameworks, crunched Excel tables of different sizes and qualities, mapped indicators, and held workshops on tracking change in networks. Doing all of this is way more than a job to me. I have met wonderful people on this path, have been part of impactful projects and really had the feeling of being able to contribute in a meaningful way.

To me, impact evaluation is an ambitious, creative and collaborative application of complexity science (more on that later). It can be a deeply empowering process that reveals hidden opportunities and structural challenges, creating empathy between groups of people.

And it can be harmful.

The dangers of linearity

Let me share a definition with you to explain what I mean:

“An impact evaluation analyses the (positive or negative, intended or unintended) impact of a project, programme, or policy on the target population, and quantifies how large that impact is.”*

I agree with that definition in general, yet when it comes to the details in language, my opinion differs significantly. For example:

- Nobody is or should be a target. We don’t shoot projects, programs or policies at people, we work with people.

- Quantification plays a role, but we should also qualify impact.

- It is not said who has the power to define “positive or negative”, and “intended or unintended”.

These are not simply trivial semantic differences. All too often I experienced situations where impact evaluation was used by organisations to prove and validate the effectiveness of their services, rather than to truly understand the perception and consequences of what they offer.

Here is an example of what I mean: A couple of years back I had the opportunity to visit cocoa farmers in Ghana for an impact evaluation for an NGO. We found out that, yes, the NGO’s activities are actually having an effect and are contributing positively to farmers’ income. But we did not capture in writing the fact that most farmers stopped growing subsistence crops for their own consumption, hence making themselves more vulnerable to global trends and market prices. A few months after I left, the market price for cocoa dropped significantly. We did not capture it as it was not part of our evaluation framework or our mental model about what counts as relevant information.*

This is what happens all too frequently: We have pre-defined and pre-conceived notions of what counts as a data point, and what doesn’t. This again is usually based on a linear model of thinking (aka “A” leads to “B”), not accounting for the complexities and intricacies of human interaction and social systems. I have talked to so many people in the field that were frustrated, stating something along the lines of “we don’t measure what is truly relevant”.

To put it another way: If empathy and understanding are not at the centre of impact evaluation, both as the foundation and the goal, then it might be (unintentionally!) used against the people we want to benefit. It’s like having a knife in your hand. You can use it to prepare a delicious meal, but also to hurt yourself and others.

About potluck dinners and “power with”

Let’s dig a bit deeper into that: We’ve learned that what we do in impact evaluation is to assess the change attributed to an intervention (a project, program, workshop etc.). You do something and then something else happens. Now, we want to understand the “somethings” and how they are connected. This is not as simple a task as it may seem. Reasons include:

- We humans love to make our own meaning. You (and your organisation) probably know what the intervention is, but others perceive it fromtheir own perspective and life reality.

- Change is like air: Ever-present and hard to grasp. The “mechanics” of change can’t be pinned down easily and require us to look at context & conditions. Similarly, we know how difficult predictions are. Should we trust the weather forecast? For the next 3 to 5 days probably, but beyond that?

- There is power in the game: Oftentimes, multiple stakeholders and their multiple opinions are involved in an evaluation. There is nothing wrong with that per se, yet it is important to acknowledge.

The art of impact evaluation, therefore, is not to publish fancy reports, but to apply it in such a way that it deepens the internal understanding of issues at hand and strengthens the collaboration between actors. When this is the case, It builds empathy and human connection, and enables stakeholders to jointly develop shared meaning and scenarios for social change and transformation.

In other words, impact evaluation is based on and deepens listening. Listening not only to people, but to their context and to groups of people, to underlying and invisible challenges and hopes.*

In a more recent project I worked on we called all stakeholders together from the very beginning. It was clear who “has the money”, but we also shared the ambition to collaborate on a level playing field. As a consequence, we co-developed the project’s vision and the evaluation framework. We made clear that the first round of data collection also serves the purpose to understand what is relevant; and that the project goals will be further developed based on the “reality on the ground” rather than the content of the funders’ strategy paper.

We created the space for a genuine dialogue, and the data collected further strengthened the mutual understanding and trust in the group and in the process. It revealed both further challenges and where the leverage points are for creating systemic impact. It also became clear that power is not only linked to money.

“What makes power dangerous is how it’s used. Power over is driven by fear. Daring and transformative leaders share power with, empower people to, and inspire people to develop power within.” (Brené Brown)*

What we did was to ask a different question than normal. The central question was not “how can one central stakeholder prove their impact?”, but rather “how can we jointly contribute to desired change for a matter that we all care about?”. Shifting the question means that stakeholders and their individual contributions are valued differently, and that the quality of interaction changes.

Speaking in the metaphor of our delicious meal: We did not go into a restaurant where you tell somebody what should be cooked for you. Rather, we sent out the invitation to join a potluck dinner. Organising a dinner in this way does not happen at random. It requires clarity on roles and contributions, as well as shared agreements (e.g. on when and where to meet). The fundamental difference to a restaurant visit, though, is that it values participation and what each stakeholder (dinner guest) brings to the table, which in turn requires a mindset of being curious and open to surprises.

So far so good, but how do we actually measure change?

Jannik Kaiser is co-founder of Unity Effect, where he is leading the area of Systemic Impact. His desire to co-create systemic social change led him down the rabbit holes of complexity science, human sense-making (e.g. phenomenology), asking big questions (just ask “why” often enough…) and personal healing. Having worked in the NGO sector, academia and now social entrepreneurship

Originally published at Unity Effect

featured photo by Adi Goldstein on Unsplash

Seeing the World Through a Network Lens

June Holley offers Network Weaving Workshop, another training slide deck for use in your organization or network. It provides an introduction to many network concepts and includes a number of activities such as speed networking, mapping your network, and the Network Weaver Checklist.

This slide deck is particularly good for sets of organizations who are not well connected. As result of this session, they would be starting to see the world through a network lens.

The slides are offered in pdf format, but we are also sharing a link to the google slides. Create a copy of the presentation and save it as a new name in your google drive. This way, you can modify them to adapt the presentation to the particular group you are working with.

Access the Network Weaving Workshop slide deck HERE.

June Holley has been weaving networks, helping others weave networks and writing about networks for over 40 years. She is currently increasing her capacity to capture learning and innovations from the field and sharing what she discovers through blog posts, occasional virtual sessions and a forthcoming book.

featured image found HERE

Businesses without Bosses: from hard-nosed leadership to sustainable, self-managing systems

As many of you know, I’m very passionate about helping people understand and experiment with self-organizing.

Joella Bruckshaw and Julian Saipe are executive coaches who have a wonderful podcast series called ‘Behind The Screen’ where they share leadership insights with high profile leaders. In this series of impromptu discussions, Joella and Julian, along with their invited guests, discuss success, the characteristics we choose to reveal, and those we choose to keep behind the screen - engaging thoughts on leadership, performance, authenticity and having fun.

In Episode 12 of the podcast series, Joella and Julian talked with me about Self-Organization.

Our conversation explored how “businesses without bosses” can thrive, just as nature’s own eco-systems do. We also discussed how coaching could facilitate a transition from hard-nosed leadership to sustainable, self-managing systems, where purposefulness itself is the outcome.

Access the interview on Behind the Screen podcast at: iTunes/Apple HERE & Amazon Music HERE

June Holley has been weaving networks, helping others weave networks and writing about networks for over 40 years. She is currently increasing her capacity to capture learning and innovations from the field and sharing what she discovers through blog posts, occasional virtual sessions and a forthcoming book.

featured image found HERE

Organizing Liberatory Networks: An Invitation

These are emerging reflections on the work we have done within networks, which includes networks for and led by people of color, multi-racial networks, queer networks, immigrant networks, and other groups that have come together to shift systems towards equity and liberation. In particular, we want to name the leadership of Black and Indigenous women and femmes within these networks who contribute wisdom and emotional labor to support the work of these groups. We are also grateful for the wisdom shared by The Queen Sages, Child Care for Every Family, Protecting Immigrant Families, All Above All, Transformative Leadership for Change, Center for Innovation in Worker Organization and their Women Innovating Labor Leadership Program, and all the participants of the movement network organizer pilot.

The events of the last year, continuing to this year, have called on us to deepen practices that center intersectionality, solidarity, racial justice, and mutual aid. Organizers have been working one-on-one with people in communities and side-by-side with other organizations to support people’s immediate needs and build movements for love, dignity, and justice. Along the way, organizers have deepened their praxis on transformational organizing and working in networked ways. (We think of praxis as having a stance of discovery and learning as we experiment with and embody aligning our values, beliefs, and worldviews with our practices, mindsets, and ways of being.)

This blog shares what we are learning from organizers and grassroots groups about organizing with and in networks. These insights are constantly evolving and changing so we invite organizers, networks, capacity builders, and those who fund this work to learn, practice, and deepen our learning together on how to catalyze and shape liberatory networks. We are in a moment of possibility where we can hold the learnings from the last year(s) and continue to build, nourish, and sustain networks that disrupt conditions in the sector to advance love, dignity, and justice.

What Are Liberatory Networks?

Over the last decade, we’ve learned a lot about how to nurture and sustain powerful, equitable networks (by network we mean collective efforts that seek to align people across constituencies, geographies, issues, or movements to accomplish something no individual entity could do alone). Allen Kwabena Frimpong at AdAstra Collective has introduced us to different types of networks such as the decentralized, self-organized network with many overlapping clusters and a strong periphery. Folks like Deepa Iyer and June Holley have helped us to understand the roles individuals play within networks and movements, such as “the guardian” who creates the conditions for the network to thrive, or “the healer” who mends harm within it. Finally, organizers have helped us understand the essential capacities networks need to be sustainable and advance equity, such as weaving relationships that center equity and trust or managing polarities, conflict, and the distribution of power and resources.

As working in networked ways becomes the norm, we are seeing professionalization, technocratization, and the loss of the relational soul of many of our networks. Thus, we want to elevate what we are learning from folks of color and queer folks who have been catalyzing, co-creating, and evolving networks that embody transformation at the personal, organizational, and network levels. These networks are interdependent, relational, evolving ecosystems where we can be our whole selves, be mutually supportive and accountable, and co-create new futures—where both what we are doing together and how we are doing it are important and integral. In order to distinguish the work of these groups from conventional networks, we refer to them as “liberatory networks.”

Liberatory networks create space for long-term visioning, self-awareness, naming and addressing the oppression that is replicated in our strategies, and the healing of personal suffering. They support individuals to ground in their ancestral and spiritual roots. They have mechanisms to hold people through traumas, triggers, harm, and internalized oppression in ways that restore relationships and connection. Member organizations are actively doing anti-racism/oppression work internally to show up in solidarity with others and in accountability with community, staff, and board.

These powerful networks are disrupting what we have been taught, and now assume, about what strong leadership and operations should look like in the nonprofit sector. Many networks and organizations are moving from solo charismatic leaders to shared leadership, from “power over” to co-powering, from top-down knowing to collective meaning-making, from defaulting to habits of white supremacy culture to practices centering BIPOC leaders and advancing the collective liberation of all people. Through these practices, liberatory networks, in turn, enable us to advance equitable systems change and shift culture overall.

Invitation to Intentional Praxis

As Stacey Abrams points out, now is the time to build the infrastructure we need to have the power to bring forth our most radical imaginations for a new society. This infrastructure will be and already is networked with clusters of organizations and individuals that are interconnected. One organization or short-term coalition cannot meet growing community needs or support healing from trauma; cannot absorb, sustain, or deepen the engagement of millions of people who want to participate; and often cannot transform society. Liberatory networks allow us to build, aggregate, and wield more power. They can provide a space to reconnect and heal from racialized harm, isolation, burnout, competition, fragmentation, and campaign-to-campaign exhaustion. They can enable us to collectively deepen our praxis towards liberation.

Organizers are important bridgers both across and within liberatory networks. When organizers have space to work with community and network members, they can co-create liberated, powerful, and creative spaces that inform and shape liberatory networks. When included in developing bold visions and strategies at the network level, organizers bring these ideas into relationships and action on the ground.

Organizers are already drawing connections within their work and learning about and co-creating liberatory networks through their own experimentation. At the same time, organizers and other network members, such as capacity builders, facilitators, and funders, could be stronger partners and architects in building and nurturing the infrastructure we need for a liberated future if there were more spaces for intentional praxis and broader sharing of these learnings across – in addition to within – networks.

What We Are Learning About Organizing Liberatory Networks

The following are praxis seeds for organizing in networked ways to advance liberation. We draw on stories shared through two pilot classes co-authors Susan, Trish, and Robin did with 29 organizers, a convening we did with grassroots leaders and funders, and our own experiences partnering with organizing groups and networks. We invite you to contribute your own insights as well so that we can continue a dialogue about organizing liberated networks. What is your praxis? How can we continue to evolve our practices to get closer to our aspirations of liberation and racial justice?

1. Centering racial equity and healing, particularly addressing and repairing inequitable distribution of power, resources, and labor

When working in and across networks, organizers are being thoughtful and transparent about how to marshall resources, recognition, and capacity equitably given current and historic racism and intersecting oppressions. Organizers spoke to three ways that they are doing this. First, several organizers shared how they use somatic practices and storytelling to support BIPOC members to develop a racial analysis, connect to ancestral wisdom, and embody what it means to center themselves. As one example, an organizer described this somatic stance: “I have my hands out; I’m open. I have one foot forward and one foot back; as a male Latino, I’m listening to women and courageously taking space against patriarchy.” Second, when individuals are grounded in their whole selves, organizers can facilitate conversations about the differences among groups. One person, for instance, shared how white and BIPOC caucuses helped develop radical relationships across racial groups. Lastly, organizers in networks are addressing inequitable distributions of labor, resources, credit, and compensation. Women of color and Black women and femmes, in particular, often hold emotional labor and relational work in networks. Participants at the NEST1 convening discussed ways to shift this dynamic by compensating women for this invisible labor, sharing or shifting responsibilities to white men, and prioritizing regional tables that center leaders of color.

Opportunities for Praxis Exploration

- Centering people of color, blackness, and indigenous peoples while de-centering whiteness

- Building a foundation of trust to recognize power differences and have courageous conversations

- Embodying love, human dignity, and compassion

- Unpacking levels of oppression while recognizing the historic social construction of racism

- Moving from oppression to liberation by reconnecting to source, story, body, and emotions (thanks to Monica Dennis for this framework)

- Attending to who does the emotional labor and how we share that or rectify it

- Managing the tensions between addressing immediate needs of communities of color and laying long-term foundations for transformation

- Reflecting on where our movements have failed to embody our values and consciously co-create the conditions for embodying them moving forward

- Centering reflection, learning, repair and re-creation as a continuous and loving process.

2. Doing the inner work needed for personal and interpersonal transformation, which is critical for nurturing radical relationships and our interdependence

There are two areas of inner work that are top of mind for organizers working in networked ways. The first area is nurturing radical relationships and connections within and across movements. Two of the organizers we work with shared that, when they had the opportunity to develop a shared political analysis and vision with a people of color caucus over the course of a two-day retreat before collaborating with the broader network, it enabled them to nurture trust, recognize shared values, and find ways to honor each person’s and organization’s contribution to the movement. Another organizer shared how they connected two groups that would not normally be allies by asking a powerful question: “What does home mean for you?” This question later led to a storytelling organizing process across multiple organizations, supporting both individual and group transformation.

The second area is embracing generative tensions as a liberatory practice. These tensions are often framed as polarities and include abundance and scarcity, conflict avoidance or expression, centralization or decentralization, focusing nationally or statewide, transparency and information overload, accountability for racialized harm and cancel culture, calling partners into a radical stance or compromising for an interim win, and so many more. Organizers regularly navigate these tensions as their context continuously evolves. This involves reframing disagreement from being divisive to being generative. Navigating tensions can deepen our collective capacity to make meaning of complex issues. It can help groups discern when our desire for resolution is rooted in our discomfort with holding multiple and different ideas (so we could get more comfortable living with conflict) and when this desire is needed to maintain the integrity of the network. Organizers further shared that they use racial healing, restorative justice, conflict resolution, polarity management, forward stance, and many other approaches to name and reconcile tensions and realign and heal networks and relationships.

Opportunities for Praxis Exploration

- Integrating head, heart, and body

- Embracing change and emergence

- Nurturing a whole person and their ways of being

- Creating space for relationship building

- Recognizing difference, naming tensions and polarities, reconciling conflict generatively, and healing harm

- Tending to well-being and sacred grounding

- Supporting self and community care

3. Shifting to more emergent and collective ways of understanding and navigating complex systems change

Organizers regularly engage community and network members to analyze systemic root causes and identify leverage points for transformation. They use a range of practices like storytelling circles and collective vision murals to do so. During the pandemic, organizers became pros at adaptation – moving to digital organizing, virtual policy advocacy, and mutual aid to address emerging community needs. They built in check-ins, yoga, breathwork, meditation, and other practices to support themselves and community members to be resilient. Organizers are always adapting as they seek complex systems change including:

- Tending to both campaigns and the sustainability of people, organizations, and the network overall

- Figuring out when all network members need to be in agreement and when a critical mass of a network can move things forward

- Having ways for parts of a network to opt in or out of democratic processes

- Flexing between decentralized experiments with liberated models and coordinated targeted campaigns

NEST convening participants also shared how networks are themselves systems, and people need well-resourced spaces to disrupt white supremacy, model liberatory ways of being with each other, and translate learnings from successes and failures without judgment.

Opportunities for Praxis Exploration

- Forging interconnectedness and interdependence and breaking silos

- Shifting from scarcity to abundance

- Embracing change and emergence while letting go of certainty and the idea that healthy networks are static

- Developing a complexity mindset, which means assuming disagreement, unpredictability, ambiguity, and emergent patterns

- Listening deeply, holding multiple perspectives (i.e., individual, organization, and network), and generating nuanced alternatives

- Experimenting as a way to take risks, innovate, and learn

4. Sharing leadership and decision-making power in ways that lift up Black and Indigenous peoples and other people who have historically been excluded from power

Sharing leadership is core to transformative organizing in networks. What this means for organizers is supporting community members to recognize and develop their own leadership, and centering Black, Indigenous, and other people of color in leadership (both of which are critical in non-network contexts as well). For instance, women of color organizers Trish Tchume and Aida Cuadrado Bozzo have worked with groups of organizers to navigate complexity and emergence (which are typical for networks), in support of a shared vision, build teams that are intentional about staying in “right relationship,” and call in community members to a liberatory stance.

Sharing leadership and power also means creating transparent feedback loops, opportunities for community members to practice different leadership roles within a network, and spaces to collectively connect to heart, body, and spirit. For instance, one organizer shared how they used salsa dancing to invite people to show up as their full self and see the different roles in a movement (e.g., lead, follower, creating space, etc.). As another example, organizers are engaging community members (who are compensated for their time), to gather community perspectives, stories, and experiences; shape priorities of the network itself; review messaging, materials, and tools that are used with community members; and co-develop actions on shared campaign tactics.

Opportunities for Praxis Exploration

- Recentering BIPOC leadership, particularly as decision-makers and liberated gatekeepers

- Cultivating not one leader but many leaders who can trade-off and play different roles

- Engaging and developing leadership at many points and levels of authority in the system

- Systems and processes for shared meaning making, co-creation, and mutual accountability

- Connect to self as a whole person and developing trusting relationships with others

- Sharing decision-making power, credit, resources, influence, and turf with attention to liberation, equity, and reparations

- Collectively determining how funding will be raised, used, and distributed in the network

5. Creating space to connect to our multiple wisdoms and intelligences (e.g., ancestral, spiritual, natural, creative, somatic, etc.)

Some organizers have long histories of connecting community and network members to multiple wisdoms and intelligences (e.g., theater of the oppressed as a somatic and artistic practice for political education). Other organizers spoke to how challenging it is to shift organizing patterns to make space for spirituality, emotions, artistic and experiential practices, and bodywork. Many organizers strive to hold themselves, partners, and community members as whole people in their full dignity, which means supporting people to develop their innate talents, decolonize, heal, and express themselves in the ways that make sense for themselves. This is critical to transformational organizing and to organizing liberated networks. Trish Tchume and Aida Cuadrado Bozzo, with Viveka Chen, Zuri Tau, Holiday Simmons, and Susan Wilcox, have developed “Calling In & Up: A Leadership Pedagogy for Women of Color Organizers,” which supports organizers in creating liberated spaces that embrace multiple wisdoms. The guide shares a range of spiritual, cultural, and somatic practices to decolonize spaces, create the conditions to live into liberation, and build and deepen relationships.

Opportunities for Praxis Exploration

- Recognizing, lifting up, and engaging wisdom in multiple forms including experiential, ancestral, spiritual, natural, somatic, art and culturally-based forms of expression and meaning-making

- Embracing being a co-learner and co-creator rather than or in addition to being an expert

- Rooting into a values-based frame

- Shifting approaches to organizing that disproportionately value analytical, intellectual, and logical forms of knowing

An Offering for Praxis

This blog shares what we’ve been learning from organizers and grassroots groups about organizing liberatory networks. We invite you to share your learning, insights, and questions so that we can continue a dialogue about organizing liberatory networks together.

How are your networks embodying liberatory network approaches?

Please share your reflections in the comments below!

1The Networks for Equitable Systems Transformation (NEST) convening took place across 2.5 days in 2019. The group consisted of network funders, participants, and intermediaries who shared space and surfaced challenges, opportunities, and questions related to their work in networks. Read more about the design of the NEST convening and key takeaways from participants here.

2Here we are not referring to an organization’s membership base since not all organizations have a membership model although there can be overlap when community members are also members of an organization.

We'd like to thank Panta Rhea for supporting the movement network organizer pilot and our efforts to share this learning with you through this blog.

About the Authors

Susan Misra’s life purpose is to work with advocates and activists to actualize their visions and values of justice and equity in their relationships, structures, and work today. She has over 20 years of experience in developing equitable, sustainable organizations and networks for movement building.

Trish Tchume is the Leadership Program Director for Community Change and comes with almost two decades of experience helping everyday people see their role in the gorgeous project of building a more just and equitable society.

Robin Katcher strengthens organizations, leaders, and networks on the front lines of social change. Her deep experience in social justice movements – as an organizer, educator, legislative advocate, and board member – informs her rigorous approach to building powerful organizations, leaders, and networks.

Natalie Bamdad joined Change Elemental in 2017. She supports Change Elemental consulting engagements through research, analysis, and project management. Her core areas of expertise include strategic planning and program design and implementation.

Natasha Winegar is a researcher, writer, communications specialist, and coach. She joined Change Elemental in 2013, and is our Research & Communications Manager. She collaborates on our consulting, coaching, and learning engagements, bringing a blend of curiosity, imagination, strategic insight, and a commitment to love, dignity, and justice.

Originally published at ChangeElemental.Org

Banner Photo Credit: Cuba Gallery | Flickr

by SUSAN MISRA, TRISH TCHUME, ROBIN KATCHER, NATALIE BAMDAD, NATASHA WINEGAR