Five Calls-to Action from the 2022 Facing Race Conference

What happens when thousands of racial justice leaders and practitioners come together after a pandemic? So much power and knowledge-sharing – and plenty of dancing and hugs, and even a few martinis!

At the 2022 national Facing Race Conference in Arizona, sponsored by Race Forward, participants were graced with gratitude for their work for racial justice, invited to be even bolder in our approaches, and instructed to avoid internal implosions at a time in which our organizations and the movement are needed the most.

I heard five important calls-to-action:

- Backlash Means We’re Winning. Keep Going!

We’re winning! The number of people of color leading and pushing change in institutions is at its highest levels. We see movement wins such as the growing people of color electorate and the halt of the Keystone pipeline. The use of the word “systemic racism” is now commonplace. We were encouraged to keep pressing forward and harder to break through on our biggest ideas. Opening plenary speakers said, “Fight for your impossible idea… and let us dream and fail.”

- Get out of Isolation. It’s Time for Reconnection!

We’ve become accustomed to quarantine and staying close to home but we were encouraged to move out of our comfort zones. Specifically, we were reminded to talk to people at their doors and to bring them back into protests and visible organizing. One speaker said, “we have to retrain people, including ourselves, to interact again, especially in person and in public.” At IISC, our mission is creating skills for collaboration and interaction. We’re exploring how we can enter and hold physical spaces with care while still centering those at risk from COVID through an equity and disability access lens.

- Don’t Underestimate White Nationalism. Expose and Bring it Down!

As distinct from the ideology of white supremacy, white nationalism is coordinated and direct action fueled by hatred and violence. Organization-building to support white racist and anti-semetic attacks and violence is on the rise and getting very sophisticated. From Boston to Michigan and Florida, leaders pointed to overt and well-organized actions in their communities from white nationalist organizations. They encouraged us to work with community organizations, government leaders, and neighbors to develop strategies to prevent their inroads and to frame messaging to drown out their discourse.

- Stop Internal Organizational Implosions. Build Organizations on Soul Work!

We heard a loud and clear call for each person inside an organization to take responsibility for extinguishing the internal fights we are waging against each other so we can focus on the external fights for justice. No organization, person, or leader is perfect so we can’t cast each other to the curb in punitive and harmful ways, stay in victimization, attack each other, and fall into gossip. They asked us to build our organizations so people can do their soul work and be liberated to do work with joy and happiness.

- Move Forward. Live into Possibility!

I was struck that you barely heard the name “Trump” around the conference. The focus was on moving and organizing for what we want and imagine. Not that we don’t pay attention to the war on our democracy and progressive values but that we go in the direction of creating even more conditions for change and living good personal lives as we do it. IISC held a workshop at the conference on fighting the return of the old normal by envisioning and leading for liberatory systems and racial justice transformation. We produced a resource guide to help you and other organizations do that while attending to the current challenges before us. Check it out.

In summary, we have power, we’re winning, and we need to reconnect and get our own house in order. Now that’s a push we at IISC appreciated and definitely needed, and maybe you feel that way, as well. We hope to see you at the next Facing Race conference in 2024.

As president, Kelly Bates (she/her) leads the strategic direction of Interaction Institute of Social Change and supports its dynamic and diverse team of consultants and trainers to meet the organization’s highest aspirations for social change and racial equity.

Kelly is a social changer, nonprofit civic leader, and lawyer who for more than twenty-five years has led advocacy, organizing, racial justice, and women’s organizations promoting collaboration, equity, and civic engagement, both locally and nationally. She strives each day to develop and embody the heart, skills, and mindset of a facilitative leader and civic innovator for progressive movement building across the country and in communities.

originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change on December 13, 2022

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Creative Freedom for True Equity

Equity is often discussed, but rarely understood in a context that speaks to the core challenges of people who are under-represented in race, religion, gender, socio economic status or who may be geographically excluded and differently abled. In particular, the necessary experiences and spaces for communities within rural Texas are just beginning to receive the attention and resources required to spark conversation and change. Paying homage to deep rooted history and lineage of community members is essential for Black communities in Bastrop County, Texas (and beyond). In Bastrop, home to 13 original Freedom Colonies, the untapped power of equity-for-all lies in the centering of Blackness. In order for our society to evolve, it is imperative to recognize Black America's contributions and sacrifices as a strategy towards equity for everyone. This has been the primary focus of my personal work, which aspires to bring about social change for all.

Grappling with the core roots of exclusion and inequity, Network Weaving helps to build a framework for connection, access, support and consistent learning– a critical necessity for many who have generational ties to this local land. In Central Texas, approaching community organizing from a network weaving paradigm has supported an evolving model of rural mental health equity in many ways by building on existing culture of community-led organizing. By providing resources for gatherings and trainings for local community leaders, network weaving has become a pillar of support for the work already being done by many on-the-ground community members of these rural networks.

As a weaver, the support of this network and the ability to work collectively and autonomously alongside like-minded people has helped me develop the courage to continue down the path of creating safe spaces for Black women and Black boys. While they continue to be challenged by those who rarely experience the feeling of being othered, safe spaces continue to be places where, as Kelsey Gladwell writes, “we can simply be — where we can get off the treadmill of making white people comfortable and finally realize just how tired we are. Valuing and protecting spaces for people of color (PoC) is not just a kind thing that white people can do to help us feel better; supporting these spaces is crucial to the resistance of oppression.”

After the George Floyd Protests, people began coming to us, as community leaders to shoulder the burden of anti racist organizing, but as a mental health clinician, I saw that my community required a more communal approach that centered their mental, spiritual, ancestral and physical health. This led me to co-create a series of social wellness brunches for Black women in central Texas, a podcast about centering community voices in healing, and the Bastrop County Black Boys Collective which aims to nurture their innovation through connection with other boys and men.

Resistance has been the bedrock to creating safe spaces for local black communities, and it has often been misunderstood as an exclusionary act. Finding the courage, self-love and dedication to create from a vulnerable place has been an emancipating experience, making it hard to return back to “business as usual.” My vision and purpose, as I reflect on my life thus far, are to find ways to enhance freedom and liberation for like-minded communities. To get to this creative utopia, I often reflect and ask myself;

- How can I continue to create spaces for renewal, healing, safety, trust and belonging?

- Who understands and can support this desire for creative freedom?

- What are my strategies to unearth the core stories around me that have led to freedom and prosperity for rural Black America?

- How can we as a collective redefine “success” to allow space for our inherent goodness?

- Where and how can I build upon my connections to others dedicated to liberation?

Through my partnership with the network weaving community since 2019, I’ve been able to form lasting relationships to other community organizers, writers, and social change agents who also see a path towards healing for the communities in which they identify. Weavers are a set of individuals looking to bring attention to the causes that they are most passionate about. Working with advocates and activists dedicated to equity initiatives has been confirmation that we have much more work to do but…I am not alone.

As a Black woman, Mother, mental health strategist, and safe space creator, I’ve been able to carve out a path of healing with my community. These experiences have enabled me to have a clear awareness of those around me and the resources needed to build upon a framework of freedom, liberation, reciprocity and resilience while redefining my understanding of self within the totality of my community.

The thought-leaders within the network have remained bold, focused on serving all populations and dedicated to creating a system of social entrepreneurs with the belief that social entrepreneurship which honors the lived-experiences of community leaders and disruptors is the catalyst towards rural social and political change.

We are innovators and creators. My legacy will be the creation of a physical space for healing, freedom, and creativity for the under-represented. As an act of rebellion and love, weaving through my social change work has helped to heal my battle with power by stepping into my potential as a Network Engine, connector and artist. Weaving has become an important aspect of reclaiming my right to connect and create with like-minded individuals. I’ve already begun to witness the shift in our local narrative, relying on the voices, contributions and vast experiences of the black community.

The function, the profoundly serious function, of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, repeatedly, your reason for being. - Toni Morrison

Krystal Grimes, M.S., LPC is the President and Founder of AMMA Empowerment Services, LLC. Krystal is recognized regionally and internationally as a safe space creator and mental health strategist. Through an intrinsic ability and desire to support others, Krystal has positioned herself as a local convener and facilitator for healing and diversity initiatives, supporting the creation of inclusive and brave spaces for dialogue and innovation.

featured image by Alicia W. Brown

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Network Weaving for Equitable Wellbeing

The following post was written for those who will be attending the Full Frame Initiative's (FFI) Wellbeing Summit in Charlotte, North Carolina December 11-14. The Interaction Institute for Social Change has been supporting FFI staff and signers of the Wellbeing Blueprint in developing network ways of thinking and doing as they work to ensure equitable wellbeing in systems ranging from health care to transportation to housing to education to legal aid to food and beyond. Feel free to sign the Wellbeing Blueprint by going to the link above and join the movement to make sure everyone has a fair shot at wellbeing!

"It really boils down to this: all life is interrelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

- Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (minister, activist, civil rights leader)

What are networks, and why should we care?

Networks are collections of “nodes and links,” different elements that are connected to each other. These nodes or elements could be people, places, computer or airport terminals, species in an ecosystem, etc. Together, through their connections, these nodes create something that they could not create on their own. This is what some might call “collective impact” or what network scientists call “net gains” and “network effects.”

“While a network, like a group, is a collection of people, it includes something more: a specific set of connections between people in the group. These ties are often more important than the individual people themselves. They allow groups to do things that a disconnected collection of individuals cannot.”

- Nicholas A. Christakis (sociologist, physician, researcher)

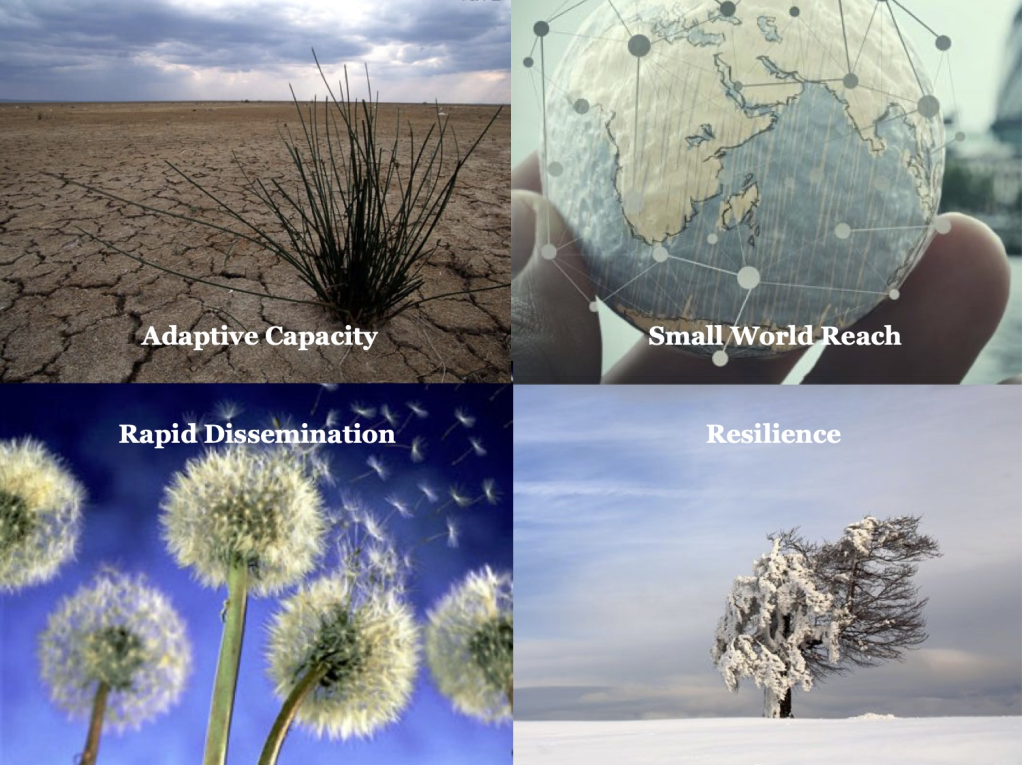

Network effects and net gains can include the following:

- Resilience - The ability for a network to weather storms of different kinds, literal and metaphorical, and to bounce back from adversity. Healthy networks can bend without breaking.

- Adaptation - The ability for a collective to change with changing conditions. Healthy networks can rearrange themselves to adjust and respond to disruptions and perturbations.

- Small World Reach - The ability to reach others relatively quickly, across different lines of separation or difference (geography, culture, sector, etc.) . Healthy networks have a diversity and intricacy of pathways, so there are a variety of ways to reach many different nodes/members efficiently.

- Rapid Dissemination - Related to reach, this is about the ability to get crucial resources out to a wide variety of nodes in a timely manner. Healthy networks can ensure that different members can get the nourishment (information, ideas, money, food, etc.) they need to survive and thrive. (1)

“Connections create value. The social era will reward those organizations that realize they don’t create value all by themselves. If the industrial era was about building things, the social era is about connecting things, people, ideas."

-Nilofer Merchant (entrepreneur, business strategist, author)

Other “network benefits” can accrue to individual nodes or members of a network. For example, when surveying members of different kinds of social change and learning networks, some of what often gets mentioned as benefits include:

- Being with other people who inspire and support me

- Learning about topics relevant to my work

- Understanding the bigger picture that shapes and influences my work

- Gaining new tools, skills and tactics to support my work

- Having my voice and efforts amplified

- Accessing new funding and other resources

- Forming new partnerships and joint ventures

What is a healthy network?

“We are the living conduit to all life. When we contemplate the vastness of the interwoven network that we are tied to, our individual threads of life seem far less fragile.”

– Sherri Mitchell/Weh’na Ha’mu’ Kwasset (Penobscot lawyer, activist, author)

A healthy network is one that is able to achieve its collective purpose/core functions, while also addressing the interests of its members, and continuing to be adaptive to changing circumstances. Some key features of these kinds of networks include (2):

- Diversity of membership

- Intricacy of connections (many pathways between nodes)

- Common sense of purpose or mutuality; a sense of a “bigger we”

- Robustness of flows of a variety of resources to all parts of the network

- Shared responsibility for tending to the health and activity of the network

- Resilient and distributed structure(s) with a variety of shared stewardship roles

- A sense of equitable belonging and ability to give to/benefit from the network

- Ongoing learning and adaptation

Like any kind of living organism, networks require care and feeding to keep them vibrant. This is where network weaving comes into play!

What is network weaving?

“A network weaver is someone who is aware of the networks around them and works to make them healthier.”

- June Holley (writer, activist, network consultant)

Network weaving is an umbrella term for the practice of network leadership/stewardship, and it refers to a specific role. If you think about weaving with fabric, it is about bringing different strands together to create a tapestry or cloth of some kind. This can create beautiful patterns, functional garments, and also strength where individual fibers might otherwise be relatively weak. The same goes for weaving connections between people, places and ideas. This is what network weaving is about!

Network weaving is not necessarily the same thing as networking. Networking is generally about putting oneself at the center and making connections to others that create what is called a hub-and-spoke network (see middle image below).

“We never know how our small activities will affect others through the invisible fabric of our connectedness. In this exquisitely connected world, it’s never a question of ‘critical mass.” It’s always about critical connections.”

- Grace Lee Boggs (author, social activist, philosopher)

A core activity in network weaving is what is called “closing triangles.” (3) This happens, for example, when we connect people we know who do not already know each other. This effectively creates a triangle of connection (see the many triangles created through the connections in the left hand image above). These triangles, by extension, can bring the connections that those three people know together, potentially creating more diversity, intricacy and robustness in a larger network (see image below). This is how we can begin to realize a sense of abundance, if these many connections are actively engaged, sharing, contributing and caring for each other and the whole network.

The work of network weaving is also about strengthening existing connections, keeping them warm and engaged. This can happen through asking questions, making requests and offers, and sharing resources of different kinds. Beyond this core function of supporting greater connectivity, network weaving can also be about supporting greater alignment and coordinated or emergent/self-organized action in networks. Other key activities for weaving and activating networks include: designing and facilitating processes to achieve a sense of shared identity/destiny, creating conditions for self-organized and emergent action, curating resources, creating diverse communication pathways, and helping to coordinate joint ventures.

What do networks and network weaving have to do with a fair shot at wellbeing?

“Connectedness is a social determinant of health. The degree to which we have and perceive a sufficient number and diversity of relationships that allow us to give and receive information, emotional support and material aid; create a sense of belonging and value; and foster growth.”

- Katya Fels Smyth (wellbeing/justice advocate, Full Frame Initiative founder)

Wellbeing, as defined by the Full Frame Initiative (FFI), is “the set of needs and experiences that are universally required in combination and balance to weather challenges and have health and hope.” FFI notes further that everyone is wired for wellbeing, but we do not all have a fair shot at the core determinants of wellbeing, or what FFI uplifts as the 5 Domains of Wellbeing. (4)

- Social connectedness to people/communities that allows us to give and to receive, and spaces where we experience belonging to something bigger than ourselves.

- Stability that comes from having things we can count on to be the same from day to day and knowing that a small bump won’t set off a domino-effect of crises.

- Safety, the ability to be ourselves without significant danger or harm.

- Mastery, that comes from being able to influence other people and what happens to us, having a sense of purpose and skills to navigate and negotiate our life.

- Meaningful access to relevant resources like food, housing, clothing, sleep and more, without shame, danger or difficulty.

The first domain above has clear connections to networks and network weaving. Being embedded and engaged in supportive social networks is a great contributor to individual and collective wellbeing! Beyond this, being connected to others in authentic, caring and mutually rewarding webs of relationships can contribute to a sense of stability, safety, purpose, as well create access to resources (financial and otherwise) that sustain and enliven us. So let’s notice the networks around us, who is in them and who is not, who has access to the five domains and who does not, and invite others to do the same. Ask, ‘What systemic/structural changes need to be made for greater inclusion, equity and belonging?” And then together, let’s weave our way to everyone having a fair shot at wellbeingll!

“i think of movements as intentional worlds … not as an unfolding accident of random occurrences, but rather as a massive weaving of intention. you can be tossed about, you can follow someone else’s pattern, or you can intentionally begin to weave and shape existence.”

- adrienne maree brown (author, doula, activist)

For more on network weaving, see:

- 25 Behavior That Support Strong Network Culture

- 3 Mantras and 3 Small Moves for Advancing Networks

- Network Bridging: How a Regional Network is Creating New Connections, Flows and Opportunities

1. See NET GAINS: A Handbook for Network Builders Seeking Social Change https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238708418_NET_GAINS_A_Handbook_for_Network_Builders_Seeking_Social_Change

2. More on the health of networks can be found here, in the work of Dr. Sally J. Goerner - https://capitalinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/000-Goerner-Regenerative-Development-Sept-15-2015.pdf

3. See more about network weaving and closing triangles at http://www.thenetworkthinkers.com/2009/11/network-weaving-101.htm

4. https://fullframeinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Five-Domains-of-Wellbeing-Overview.pdf

About the Author:

Much of Curtis Ogden's work with IISC entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food public health, education, and economic development systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change on Nov 29th & Dec 6th

featured image found HERE

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

A Future for All of Us

AN EXCERPT FROM RACE FORWARD'S REPORT ON PHASE 1 OF THE BUTTERFLY LAB FOR IMMIGRANT NARRATIVE STRATEGY

IN 2018, DURING THE HEIGHT OF THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION’S attacks on migrants, immigrants, and refugees, a landmark study warned pro-immigration forces that “attitudes towards immigrants and immigration are extremely complex: even those who appear to be pro-immigrant (who even think of themselves as pro-immigrant) are often very conflicted.”

A majority of Americans support the idea that migrants, immigrants, and refugees deserve to belong and thrive. Many recoiled from horrific images of family separation, violence against migrants at the border, and white nationalist violence against immigrants in cities like El Paso. Yet when the country locked down under the threat of the coronavirus and the Trump administration nearly shut down the entire immigration system, too few stood up to challenge these severe policies.

How does the pro-immigrant movement begin to confront such contradictions? To begin to answer this question, it might be better to look not to the tools of policy in the realm of traditional politics, but the tools of narrative in the realm of culture.

Cultural change precedes social change. Narrative drives policy. This is why we must be as strategic and rigorous in building narrative power as we are in building all other forms of power. Narrative is the space in which energies are activated to preserve a destructive system or build a better world for us all.

Right now, anti-immigrant forces continue to shape the dominant narratives around migrants, immigrants, and refugees, claiming that they are exploitable, expendable, criminal, and unworthy of equal treatment. These dominant narratives have fostered policies that terrorize migrants, immigrants, and refugees emotionally, economically, and physically. They protect a harmful status quo.

We are called instead to forge a new consensus. We must move a majority of people to imagine and act to create a world that does not yet exist. In order to make this world a reality, we need to orient ourselves toward the world we want to win, and make this future tangible and irresistible to a majority.

In this first phase of the Butterfly Lab for Immigrant Narrative Strategy, we hosted sixteen leaders to develop, test, and align narratives that meet our current political moment and advance our vision for the world we want to build. We supported their work with research,coaching, and funding. We were heartened by the many breakthroughs we made together.

Our work in the Butterfly Lab in this first phase affirms what we have known and gives us some directions to advance the movement towards more strategic alignment. We found:

• Nearly everyone believes immigrants deserve to belong and thrive.

• But many find it difficult to imagine an America in which that may be true.

• Core audiences respond well to all tested narratives, including those focused on shared humanity, compassion, dignity, and respect.

• But stretch audiences do not respond well to those aforementioned narratives. They do respond well to narratives of striving, responsibility, and liberty.

• Our narratives need to make sense of the past and present, and point toward immigration futures that are compelling to all.

Immigration remains the “third rail” of progressive politics. And yet, even in these discouraging times, we believe it is possible to win. When we look at the cultural transformations that other recent narrative movements—from “love is love” to #BlackLivesMatter—have made, we see pathways forward. Over a long period of time, many people built narrative infrastructures that could work in concert with policy infrastructures. When narrative power-building met the social moment, cultural inflection points turned policies previously thought unreasonable into ideas worthy of serious consideration. With immigration, we too must invest in narrative as key to winning power for migrants, immigrants, and refugees.

In this report, we share with you learnings, frameworks and tools, and insights into directions we can take to move forward together. Whether you are an advocate or artist, a long-time veteran of the culture wars or thinking about how to apply narrative or cultural strategy for the first time, this report is designed to work for you.

It is also designed to help you think and act at multiple scales—locally, regionally, or nationally—with rigor, alignment, and purpose. The best narrative strategy should foster a unity of intention with a diversity of voices, approaches, and methods. It should help people work together with a sense of alignment along different timelines and fronts. We want this report to be used to build skills, capacities, and networks within the movement, and, above all, to help all of us approach narrative strategically.

You can access the full report at Race Forward HERE or at Network Weaver HERE

You can also access a standalone version of the toolkit HERE

Race Forward catalyzes movement building for racial justice. In partnership with communities, organizations, and sectors, we build strategies to advance racial justice in our policies, institutions, and culture.

About the Butterfly Lab: Race Forward’s Butterfly Lab was launched in 2020 to build power for effective narratives that honor the humanity of migrants, refugees, and immigrants, and advance freedom and justice for all.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Getting to the Goods (and Beyond “Folded Arms” Syndrome) in Impact Networks

“Your generosity is more important than your perfection.”

Seth Godin

Over the past 20 years of working with a variety of social change networks, I have observed a common dynamic surface after the initial enthusiasm and launch phase. As happened recently with a place-based network about a year into its development (navigating COVID and political uprisings along the way), some members started to bang the “What have we actually done?” drum. Contextual crises notwithstanding, this is not an inappropriate or unhelpful question. As important as relationship and trust-building is, there can come a time when people want to know … “So what?” Sometimes this comes from what we might call more “results-oriented” people in the network. Or it may come from the more time-strapped and stressed, those from smaller organizations, or those who just genuinely don’t see the return on their investment. When this has come up, and people are either holding back (“folded arms”) or threatening to walk, I have witnessed and facilitated several different ways of moving through the real or perceived lack of progress.

- “If you want it, then you better put a ring around it” – In one instance, the convening team of a state-wide network essentially drew a line around all of the network participants and started claiming their successes as network successes. This might sound a bit shady, though it was not done in that spirit. By celebrating “your success as our success,” people felt appreciated and started to turn towards one another and see themselves as a bigger we. They didn’t have to wait to get to mass action. Smaller subsets having success counted.

- Get a quick win – In another state-wide network, fraught at the outset by folded arms despite the fact that people would regularly physically show up for meetings, a network coordinator seized upon a timely policy advocacy opportunity that surfaced, which resulted in a mass outpouring and a legislative win. Nothing sells like success. That early victory got people eager to see what else they might be able to accomplish and they settled in for some more relationship-building.

- Collect and share connection stories – We know that relationship-building is not just about the relationships. It can lead to new partnerships and projects. Often this happens at the start of a network, but is not tracked. We worked with another place-based network that intentionally set out to track the results of connections made in and through the network, and then shared these with the network as a whole. More about connection stories here.

- Highlight the unusual and adjacent conversations – What makes many of the networks we work with unique is that they bring together people who do not often work with each other. Highlighting this and also what emerges out of novel interactions across fields can make “just talking” into exciting explorations and engines of innovation. For a little inspiration on this front, see “Why the most interesting ideas happen at the borders between disciplines” from Steven Johnson at Adjacent Possible (!).

- Pump people up, individually and collectively – Let’s face it, in these times (and really all times), expressing genuine appreciation can go a long way. We work with a network convenor who does this wonderfully, tracking and celebrating people for their individual contributions outside of network gatherings, and constantly speaking to the power and potential of the collective. She just makes people feel good! This can make the proverbial “marathon, not a sprint” more enjoyable.

- Get a super weaver going – Having a really adept and energetic network weaver can make all the difference in the early stages of a network. We have seen the impact this can have when ample capacity is created to regularly check in with people, listen to them, make connections between different needs and offers in the system, and encourage people to share more with one another. When those exchanges start happening, the “there” there is often more apparent.

- Lift up the network champions – Generally there is a small group of people who really appreciate and lean into the value of the network from the get go (gratefully receiving and using resources that are shared, following up with new connections, testing out new ideas, leveraging the network as a platform), making it happen and not waiting for it. Observing this, capturing it, and sharing it with the network can help make the point that the network is what people make of it and give ideas for how to make this happen.

What have you done to successfully navigate impatience and intransigence in impact networks?

About the Author:

Much of Curtis Ogden's work with IISC entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food public health, education, and economic development systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Belonging to ourselves, each other, and the earth

From decolonization to... re-indigenization?

I’ve found myself increasingly interested in the promise of ‘embodiment’: the possibilities inherent in the seemingly simple act of being attuned to what our bodies are telling us. Thus far I’ve explored that concept primarily through the lens of the self, of the ‘I.’ But there’s more to it than that, something that feels powerful.

So today I want to explore the transformative potential of learning to sense and feel at three different levels: what in Building Belonging we call the levels of “I, We, World.” The promise of belonging is the promise of integration: it’s about belonging to ourselves, to each other, and to the earth.

“All transformation is linguistic”… and embodied?

This topic is especially hard to think and write about clearly because we lack the language. It’s difficult to conceptualize something if we can’t name it (an insight made famous in Betty Friedan’s discussion of “the problem that has no name.”) It was perhaps with this in mind that Peter Block provocatively wrote “All transformation is linguistic.”

I think he’s right… and the sentiment is incomplete. I do think the power of naming something is itself a transformative act: it allows us to see things in a new light, to understand an aspect of our experience that had thus far remained inaccessible. As Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote:

Language is the dwelling place of ideas that do not exist anywhere else. It is a prism through which to see the world.

But language is a starting point for transformation; it creates possibility. To realize that potential, however… requires embodiment.

This is the core insight of the emerging field of somatics, which deals with the “soma” (the Greek word for “body”). It’s at once an obvious and a radical idea: of course we move through the world in physical bodies, and of course those bodies inform our perceptions. And yet: Western culture tends to dismiss any forms of knowledge or information that are not “rational,” and emerging from the brain (I think, therefore I am). Indigenous cultures the world over have always held a more expansive view of human experience, talking instead of the heart, mind, body, and spirit. As Pat McCabe (Woman Stands Shining) notes,

The intellect is the least reliable way of knowing anything.

So I want to explore here (as always) the possibility of the both/and. Yes there is a power in naming something, in rendering a concept intelligible and accessible through words. And that’s not enough. There are other ways of knowing, feeling, and sensing… and it is these other ways that I want to explore today… at the level of I, We, and World. As MawuLisa Thomas Adeyemo said:

If we listen to our body, there is so much we can learn.

Belonging to ourselves: decolonization

There has been an emerging discourse in recent years about decolonization. There’s more there than I can unpack in this post, but the core concept is captured in the word itself: it is the antithesis to colonialism. It is a process of undoing, of unlearning… of practicing a different way of being.

Colonization is about conquest, growth, domination, enclosure, enforced scarcity, certitude about a singular way of being… it demands assimilation. Decolonization invites us to return to a world before colonization, to undo the ravages of the colonial mindset: to replace domination with partnership, growth with regeneration, conquest with harmony, scarcity with abundance… and embracing multiple ways of being. Decolonization invites a return to right relationship: with ourselves, each other, and the land on which we depend. We can understand colonization as a form of trauma at multiple levels. As Susan Raffo reminds us:

All trauma is collective, but we experience it individually.

This experience of trauma and fragmentation inspires resistance; humans are resilient, and we seek re-integration. Quoting Jacqui Alexander, the Gesturing Toward Decolonial Futures collective (amazing name!) puts it this way:

The material and psychic dismemberment and fragmentation created by colonialism also produce “a yearning for wholeness, often expressed as a yearning to belong, a yearning that is both material and existential, both psychic and physical.”

Yes. That’s it: a yearning for wholeness, for belonging. This is the desire animating the decolonial urge.

I’m coming to believe that the surest and swiftest path to decolonization is through embodiment, through learning (remembering) to feel and hear what our bodies are telling us. I was delighted to finally find the word for this last year: interoception describes our felt sense of our body’s internal states (hunger, anger, tightness in the chest, lump in the throat…). This is where most somatics work is done: at the level of the ‘I’ and our relationship to our own bodies. And in a cultural context that teaches us from our earliest ages to disregard and override what our bodies are telling us… it’s revolutionary work.

So here’s the idea I want to offer here: interoception (intentional embodiment) is one powerful way we can practice the art of decolonization. It is about reconnecting with ourselves, and orienting toward this truth: the body knows… if only we listen to it. There are many ways to practice: yoga, somatics itself, other forms of bodywork that invite deeper attunement to what our bodies are telling us.

Belonging to each other: cultural somatics?

Here’s another truth I’m coming to: all transformation is relational. If no one is an island… then surely our efforts to transform must start from that premise? Here’s Parker Palmer:

If we are willing to embrace the challenge of becoming whole, we cannot embrace it alone—at least, not for long: we need trustworthy relationships to sustain us, tenacious communities of support, to sustain the journey toward an undivided life. Taking an inner journey toward rejoining soul and role requires a rare but real form of community that I call a “circle of trust.”

Here again words fail us. I’ve been looking for the word that describes sensing into a collective: picking up the vibe in a room, feeling each other without touching. We all do it all the time… how can there not be a word for it? If you know the word I’m looking for, please share! Other languages besides English also welcome (not surprising that the colonizers lack words for a decolonial construct…)

There are some concepts that get close: “co-regulation” describes the idea that we synch to each other’s moods. But the concept I find most enticing here I first encountered through Tada Hozumi in their exploration of “cultural somatics.” Here’s how Prentis Hemphill puts it:

Culture is a place to tend to our collective embodiment.

Basically, the idea is that we have a collective “soma”: our individual bodies are part of a broader whole that we can feel and sense, and which exerts an influence on us. I think we all know this to be true (at least the idea that we are subtly influenced by those around us), but we don’t often acknowledge that reality. As Charlotte Rose observed:

We are animal bodies near other animal bodies. And we influence and impact each other all the time.

I’m not sure exactly what good practices are here for learning how to practice collective embodiment. I feel confident in echoing the refrain that transformation is inherently relational, and therefore the first thing we must do is find a community within which to practice. Brené Brown had a beautiful line here:

The key to building a true belonging practice is maintaining our belief in inextricable human connection. That connection—the spirit that flows between us and every other human in the world—is not something that can be broken; however, our belief in the connection is constantly tested and repeatedly severed.

I would go farther: it’s both a belief and an opportunity to practice in community. Skillful facilitators can help us; Ria Baeck talks of “collective presencing” as one methodology, but honestly this remains an area of inquiry for me. How can we learn to sense, feel, and act on collective embodied intelligence?

Belonging to the world: re-indigenization?

Our relationship to land is a whole post in its own right… I just want to touch on one concept here. I believe that disconnection is core to our current crises, and that re-integrating is a huge piece of the solution. Our loss of connection to land remains an open wound that we haven’t addressed… and I don’t see a way forward that doesn’t involve repairing that wound.

Indigeneity at its core is about belonging to land: it’s about living in right reciprocal relationship with the earth. Most of us have lost that. Derek Rasmussen had a beautiful article for YES! Magazine where he contended that we (White people in western cultures in particular, but to some extent all of us) are the first non-indigenous civilization in the history of the planet. These different forms of disconnection are of course related: to be separated from land is also to be disconnected from people, from our ancestry, and therefore from ourselves. Gibran Rivera observed:

We are the first generation to steal from our descendants, because we have forgotten our ancestors.

It affects all of us, for by now nearly all of us have been forcibly displaced by factors beyond our control. As Simone Weil wrote in her classic The Need for Roots: “Whoever is uprooted himself uproots others.” This is not to erase agency or accountability, but to acknowledge a long history of colonization (and trauma) that underlies its contemporary manifestations. Wendsler Nosie, a spiritual leader to the Apache living on San Carlos Apache reservation, explains:

When native people talk about decolonizing, you know everybody has to become decolonized. Everybody has to wake up to what is happening. White people are the oldest people that are colonized, then the rest of us we come after that. We’re all blind from being colonized.

The idea I’m trying to convey here is that the earth (the entire planet as a whole, but more specifically the particular land where we find ourselves) has its own “soma” that we feel, sense, and respond to. This is literally true, not a matter of spiritual conjecture. Here’s David Abram:

The body is always in a subtle interaction and engagement with the large vast body of the Earth itself.

Increasingly scientists are “discovering” what indigenous people have long acknowledged: we are inextricably connected. Greater Good Science Center recently ran a podcast on why we enjoy nature exploring what happens in our brains as we interact with the natural world… it is literally restorative for our brains and bodies. Anyone who has breathed the smell of a forest after a rain can attest to a truth science is now confirming. Robin Wall Kimmerer summarizes the research:

Breathing in the scent of Mother Earth stimulates the release of the hormone oxytocin, the same chemical that promotes bonding between mother and child.

As any gardener or farmer can attest, we all know this, deep in our bodies. We just don’t often stop to acknowledge that fact. I was reading the children’s classic Heidi with my 6-year-old where the narrator observes:

It is good to be on the mountain. Body and soul get well, and life is happy again.

Healing the land is healing ourselves

I found myself nodding along as Kim Smith, an indigenous Diné organizer explained that violence to the land is violence to ourselves. This landed with the ring of truth: it explains the visceral feeling I get when I see a clearcut in an otherwise majestic forest, or oil-soaked animals washed up on the shore after an oil spill. How else to describe that sensation if not pain? Loss?

But this too points the way forward, for the inverse is also true. As Shane Bernardo reminds us:

In healing the land we are healing ourselves, and in healing ourselves we are healing our ancestors.

But there is a sequencing here. As Glennon Doyle wrote in Untamed: “nothing can be healed if it’s not sensed first.” Channeling trauma researcher Bessel van der Kolk, Maria Popova explains:

In order to change, people need to become aware of their sensations and the way that their bodies interact with the world around them.

Again, words fail us. I believe re-indigenization is the process, but what is the name for the practice, for the act of sensing/feeling our interdependence with the earth? I just finished reading Black futurist N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, and she introduces the word “sessing” to describe this (makes me think of how animals can detect earthquakes before humans… perhaps we too could cultivate that skill?)

The closest I’ve been able to find outside the world of sci-fi is the concept of “entrainment”: the notion that bodies (including objects we would consider inanimate!) have a tendency to synchronize when in contact over time.

Names are the way humans build relationship

I want to close by offering two domains of practice, returning to our theme of connecting the transformative power of language and embodiment. The first shift is linguistic: to recognize the earth and non-human life as beings worthy of respect and consideration. Here’s Ursula Le Guin:

One way to stop seeing trees, or rivers, or hills, only as 'natural resources,' is to class them as fellow beings—kinfolk. I guess I'm trying to subjectify the universe, because look where objectifying it has gotten us.

Robin Wall Kimmerer has made this a key feature of her writing and work, even offering us a pronoun echoing Le Guin: ‘ki’ (as a singular form of the plural ‘kin,’ but also a play on the French pronoun ‘qui,’ meaning ‘who’). She explains:

Names are the way we humans build relationship, not only with each other but with the living world.

“What the hands do, the heart learns”

I first encountered this concept via Movement Generation, as a welcome reminder of how humans learn and transform. Through embodied action. Katherine Gibson and Julie Graham put it well:

If to change ourselves is to change our worlds, and the relation is reciprocal, then the project of history making is never a distant one but always right here, on the borders of our sensing, thinking, feeling, moving bodies.

So… how to do that? Arawana Hayashi, creator of the art of Social Presencing Theater, offers a practice called “Body Knowing as a Vehicle for Change”:

It is an invitation to feel the connection, naturally present, between our body and the earth body.

David Abram offers another prescription:

Falling in love with the more than human earth is the deepest medicine we have available.

I’ve been ruminating on this post for a while, and struggling to find time (and words!) to convey the concepts that feel so connected to me. I’d love to know what resonates, and if you’re finding terms/ways to practice connecting yourself, each other, and the world.

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at building belonging

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

People Stitching Earth | Oppression, Healing, Liberation, and Navigating the Terrain In Between

When we made it back home, back over those curved roads

that wind through the city of peace, we stopped at the

doorway of dusk as it opened to our homelands.

We gave thanks for the story, for all parts of the story

because it was by the light of those challenges we knew

ourselves—

We asked for forgiveness.

We laid down our burdens next to each other.Joy Harjo, “Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings,” An American Sunrise

Origin Story

The first beings were not humans or animals or even plants. The first beings were river, rock, lava, and sky. Later came plants, then animals, then last of all, came two-leggeds who became easily lost and had to learn again and again in order to remember their way. This is a story of that journey—one that started in harmony and abundance and has been transformed by settler colonialism, enslavement, and their aftermath: patriarchy, extractive capitalism, collective violence against aki, the earth, and all her inhabitants. The resulting interlocking systems of oppression choke lungs, poison waters, exterminate life, and obscure the sun.

This is not a story about re-making a fictional ideal past. Harmony, in narrative or music does not preclude disagreement or conflict. This is a story about some of the ways we can return to who we truly are and how we are meant to be in right relation to each other and all beings, mortal and immortal, sentient, interdependent, free.

The Journey

During this time of the great sickness—a time of tyranny, violence and greed—people have been harmed deeply by the practices of oppression: disconnection from source (a higher power and understanding of the world as greater than ourselves such as through spiritual, natural, cultural, ancestral, and/or creative practice); dissociation from our physical bodies; distancing from our emotions; and distortion of our stories.1 Some days the effects are overwhelming; the sickness is life threatening. Some days—with rest and soup, with love and community care—there are moments of shared understanding, connection, and transformational shifts in understanding and behavior.

Beyond rest and community care, what makes these moments possible, and the potential for such moments to multiply exponentially, is not one but many things, things that operate across the dimensions of personal, interpersonal, organizational/institutional, and societal/social systems.2 For those of us working as racial equity change makers—whether as internal or external coaches and consultants, including those who work in intersectional roles as healers, artists, and liberation practitioners—there is a familiar route that embraces organic twists and turns and yields movement in the right direction.

The current emphasis in our field on trainings, assessments, and curriculum—which are all good and necessary components of intersectional racial equity and can be catalytic, if used in their full potentiality—are too often leading people into thorny thickets and near cliff edges where they give up, abandoning the journey, or worse, go back from whence they came. This is not to say that these entry points are not useful ways of understanding our contexts and our own behavior in them, but they are insufficient in supporting the integration and embodiment of new ways of being, understanding, and engaging with the world. When we practice the elements of a liberating ecosystem, we enable the seeds of training and assessments to meet the nutrients and environments needed for them to take root and grow.

There are many ways to traverse the multi-faceted and challenging terrain created by the delusion of white supremacy, but overall the best possible paths are moving in the direction of intersectional racial equity that engages people and systems in practices of healing and liberation. We liken this process to a journey in the woods. There are a number of recognizable clearings or places that support visibility and understanding. And it is in these clearings that clarity, commitment, and learning is possible.

Unlike rational and determinist approaches to intersectional racial equity—ones that center assessment tools, analytical instruments, and pre-defined linear processes—we have found that these pathways are open-ended enough to support opportunities to digest learning and engage in intentional action, through which we can engage in cycles of feedback and reflection to support unlearning white supremacy and re-membering our practices of interdependence, mutuality, and stewardship.

Complexity and Justice-Oriented Change

Advancing racial equity is complex systems change, and while working in complexity there are very, very few, if ever, “best practices”. There are more good practices and most situations require emergent and adaptive practices.

Some characteristics of complexity—as outlined by David Snowden and Mary Boone3—are contexts where:

- “Large numbers of interacting elements are involved.

- The interactions are nonlinear, and minor changes can produce disproportionately major consequences.

- The system is dynamic, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and solutions can’t be imposed; rather, they arise from the circumstances. This is frequently referred to as emergence.

- The system has a history, and the past is integrated with the present; the elements evolve with one another and with the environment; and evolution is irreversible.

- Though a complex system may, in retrospect, appear to be ordered and predictable [eg. history], hindsight does not lead to foresight because the external conditions and systems constantly change.

- Unlike in ordered systems (where the system constrains the agents), or chaotic systems (where there are no constraints), in a complex system the agents and the system constrain one another, especially over time. This means that we cannot forecast or predict what will happen.”

This articulation of the characteristics of complex systems is helpful. And too, it is important to recognize that indigenous cosmologies and teachings—particularly those from the Americas and Africa—situate a complex world in which binaries and closed systems do not exist. The cynefin model, the sense-making tool that visually represents Snowden’s complexity theory, is itself from native Welsh principles and language. The word cynefin means roughly “place of our multiple belongings.”

The metaphor of a path or route, one that is organic and emergent, has the flexibility to hold the complex nature of the change we are seeking toward equity and liberation. When traveled with practices of power and leadership sharing, committed attention to innerwork, and embracing multiple ways of knowing, we live in iterations of change that both begin to prefigure the world we want and create the necessary conditions for advancing liberation in the world we are currently living in.

Charting the Terrain

Clearing One – A Reflective Pool

There are many ways to gain an understanding of where an organization and team is in terms of living into intersectional racial equity. Many equity practitioners use written or online assessments. Others hold interviews or focus groups. Some establish storytelling circles or work together to develop murals or other forms of visual narrative. Some use a mix of quantitative and qualitative (including artistic) approaches. Regardless of the approach and the associated tools and practices, the purpose is to get a complex, aggregate picture of what is, a picture of the terrain that is so much more than an organizational map. It is a layering of perspectives that helps the organization and its partners gain some sense of the contexts and conditions comprising the culture and lived experiences of people in the organization or network.

Clearing Two – A Rocky Outcrop

Once a picture of the terrain is made visible, another clearing presents itself. This rocky outcrop is a place where everyone is able to see the full and discrete snapshots of the organization and participate in a shared meaning-making process about what these snapshots might say about the team and the organization. However, collective sense-making requires some shared understanding of the current and historical structures, strategies, and belief systems that benefit some people at the expense of others. This is a juncture in the journey where indepth, whole-system conversations are crucial to restore the very real stories of settler colonialism, enslavement, genocide, wage theft, and extractive capitalism that have largely been disappeared from and or greatly distorted in our education systems. Building on these understandings, teams can also develop a shared understanding of how the continuing impacts of these legacies and other ongoing systems of oppression and inequity interact to perpetuate the manifestations of inequity in our lives and organizations. This discordant recognition is fundamental to the path.

Disagreements about what it all means and why—this generative tension—is what pushes teams and organizations toward deeper understanding. How is it that our shared language is so full of references to militaristic strategies that supported western expansion, manifest destiny and Native genocide? And how is it that the end of the enslavement of African and then African American people has done little to shift the fundamental economic, health, educational—insert just about anything here—disparities between whites and Blacks? The actual questions that teams grapple with have a lot to do with who’s on the team, their lived, racialized experiences, and the depth of their power analysis.

What matters is that teams are moving towards a shared understanding that interrupting current, intersectional racial inequities isn’t possible without having a depth of knowledge about historical inequities and the practices and systems that support their perpetuation. In this rocky outcrop, teams will often read, attend workshops and trainings, participate in caucus or affinity groups to support interrupting internalized oppression and internalized privilege. This learning journey is essential and what it entails depends on who is on the journey together. Among people of similar racialized identities it may mean grappling with global colonialism and the ways that it has impacted different peoples and different families’ histories. Healing often becomes a central focus, calling in ritual and ceremony to support the processing and release of past and present trauma.

This can be a difficult time in an organization. The fallacies that held the team together have been stripped away. But nothing new is yet in its place. It is a time for care and humility. It is a time to support the ingestion and digestion of the pervasive, corrosive presence of racial equity, making space for the restoration of our collective humanity within and across all racialized groups. It is a time for reconnecting to source, reengaging our bodies, reclaiming our emotions, and reweaving the fullness of our stories. This can mean a necessary, intentional, and sometimes scary unmooring in the day-to-day. And too, it is an opportunity for people to show up differently and build the muscle and heart necessary to get to the next evolution in the process. It requires cultivation of courage, humility, and room for risk-taking, as well as tools supporting accountability and collective tending to harm. This place demands space and time. This place requires more of us than we have sometimes been able to give. There is a necessary clarity that comes from such disruptions. As Norma Wong says, “transformation requires agency.” Some people may, in fact, choose not to move with their team or organization. And that is part of the journey too.

Clearing Three – A Sudden Vista

Through a commitment to authenticity and rigor—and doing the necessary work of deepening our understandings of historical and current conditions that affect our individual and collective experiences—we come to a sudden vista, an opening in our capacity to see a different future. A future where we all have the ability to thrive.

It is here that a visioning process can truly expand our shared picture of a liberated and liberatory future. From this vision, we can outline the values and principles that guide how we be with each other in liberating ways and define some key short term and long term transformation efforts, arriving together at those aspects of the organization that, if transformed, would enable people to experience an actual taste of equity in the immediate term while working on efforts to change the organization overall in the long term.

What we are creating is not new, yet it can be wholly unfamiliar. However, we have everything we need to make this visionary future possible. It simply requires courage, imagination, and the willingness to move as if we have one foot firmly on land and the other submerged in the tumultuous and profuse waters of the sea.4

Clearing Four – A River Flows

Once the vision, values, hopes, and dreams, the team can start developing some focused priorities and goals and the implementation effort begins to flow. But equity transformations are always a mix of inspirational visions and more tangible decisions and practices. Weaving across the two is the art of advancing complex systems change in which we are developing experiments across the organization’s functions and programs. Or it might be one or two short and long term efforts from which the team and organization is continuing to learn and to refine in ongoing cycles of reflection and growth. What matters is that the effort is continuous and fluid, and that the fluidity takes into account boulders, logs, beavers, otters as obstructions are also natural innovations to the existing ecosystems. Throughout this process, the team is meeting current capacity and emerging circumstances in ways in which both the vision of equity and the realization of equity are contiguous tributaries in the river’s powerful flow.

Context Affects the Terrain

While we are all swimming in the torrential waters of racial inequity and other intersectional forms of oppression, we are affected differently. Some are buoyed by floatation devices. Some are carried along by speedboats. Others are fighting to keep their airways above the surface of the water. The same is true for leaders, teams, organizations, and networks.

To make sense of these differing contexts—at all of the levels of racial oppression including internalized, interpersonal, institutional and systemic—we are going to describe differing approaches based on where different types of individuals, teams, organizations and networks live along a white dominant-to-liberatory spectrum: 1) White Supremacy Culture, 2) Multicultural Stance, and 3) Pro Black and Indigenous.

While such classification efforts are inherently overly simplistic, there is sufficient value in outlining different approaches based on these categories, contexts and associated conditions.

1) White Supremacy Culture (aka “The Delusion of White Supremacy & the Culture that Upholds It”)

In an organizational culture of white supremacy, organizations are habituated to working in ways that uphold the delusion of white supremacy whether intentionally or not. These cultural practices have been laid out in the work of Tema Okun and continue to be deepened by other racial equity practitioners. Initially identified as thirteen habits, the framework has evolved to include nuanced descriptions of behaviors that reify inequity, transactional relationships, and oppressive power structures. These cultural habits are exemplified by valuing perfectionism, individualism, fear, right to comfort, competition, urgency—and drive most organizational decisions and overall organizational culture in white dominant organizations.

These organizations are most often:

- White led and/or have a history of white leadership and predominately white staff (not always white-led; may include people of multiple races at various levels of the system but not in large numbers in leadership and if so, not for very long);

- Equity focus is on diversity, equity & inclusion (DEI), with an emphasis on diversity; and

- People exhibit and experience disconnection from source (a higher power and understanding of the world as greater than ourselves such as through spiritual, natural, cultural, ancestral, and/or creative practice); dissociation from their bodies; distancing from their emotions; and distortion of their stories.5

- There are also historically people of color-led organizations that operate predominantly in this fashion; most often they are in areas of work that are deeply steeped in white supremacy culture such as some legal, policy, research, philanthropic and merit-based youth-serving organizations.

Deep equity work in this context focuses on making visible the ways in which white supremacist ways of being and doing are operating as an uninterrogated norm which serves to reify white leadership and the myth of white supremacy and/or undermine the wisdom, gifts, and value of BIPOC people. Organizations in this category are often set up to support the learning, comfort, safety, and power of those in leadership and particularly white leaders. Change processes can unintentionally replicate these patterns at the expense of native people and people of color.

Racial equity change makers will often focus on cultivating equity-based awareness and understanding with white leaders in the system to ready them and thus the organization for deeper equity work. This aspect of the change effort can be very depleting for staff of color in every level of positional power as well as for all staff with less positional power within the system. The tax of this effort is in direct relationship to white leaders willingness, courage and capacity to develop a baseline understanding of structural racism and intersectional elements of oppression. If leaders are resistant to deepening their awareness and/or actively suppressed learning then little progress can be made without developing alternate leadership structures to support the organization in its evolution.

2) Multicultural Stance

In multiracial/multicultural contexts, organizations tend to exhibit characteristics of both white supremacy culture and what Okun would call “antidotes.” In this instance, an organization might be more recently led by people of color and/or have significant numbers of people of color throughout the organization including on the leadership team. In this context, the racial equity and liberation (REAL) work is more often focused on equity, which is made possible by the fact that people in the organization have a solid understanding of structural racism and intersectional elements of oppression.

The organizations are often actively seeking to disrupt the habits of white supremacy culture and people have more shared practice of expressing the harm caused both within and beyond the organization. However, having not yet fully developed the muscles of an equity-based organizational culture, the organization and its leaders will often default to white supremacist ways of working in urgency or in high-stakes decision-making, for example relying on positional power instead of embracing wisdom, experience, and skill-sets from multiple people in the system and therefore have trouble implementing equity-based systems change internally.

While all racial equity work needs to center healing, the work in multiracial/multicultural contexts often necessitates a focus on healing at intra-personal, interpersonal, and organizational levels simultaneously in order to create the needed conditions for equity-based systems change. REAL change in this context is about unlearning our beliefs and related actions as a result of internalized oppression and our complicity with white supremacy as people of color. For white people in all contexts, the work is about interrogating internalized white supremacy so that long standing ways of maintaining privilege are dislodged, making space for new ways of living and being that don’t center whiteness and the power it exerts in explicit and implicit ways. Specifically, in multiracial/multicultural contexts, white people tend to have more systems based understanding but are often still struggling to recognize that impact is not exclusively the result of individual intention. The arc of learning in this context is to develop a more complex understanding of the relationship between “it’s all my fault” and “it’s all the systems fault” in order to recognize that—because of race, power and privilege—they are both simultaneously true. In order to live into this complexity, it calls on all of us to begin to embody new ways of being.

3) Pro Black and Indigenous

In contexts where Black and Indigenous people, wisdom, and cultures are centered, organizations are led and predominately composed of multi-identitied or single-race identified Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) that have done work to address anti-blackness and anti-indigenity as a collective. The organizational vision and mission are rooted in social justice and liberation. People exhibit greater connection to source. They are in touch with the wisdom of their bodies and their emotions and are resourced by and able to be in whole and simultaneous stories. The focus of the work is beyond equity toward liberation and sovereignty.

In this context, healing work (individual and collective) is both foundational and ongoing as the organizational culture exists in a wider, toxic, and systemically oppressive society. In addition to engaging in healing and liberating practices, liberation requires continuing to address inequities; building our collective muscles for engaging in generative conflict, giving and receiving feedback, and holding each other in loving accountability; in addition to developing and evolving more equitable power structures and practices. It takes collective care and courage to embody and enact the systems, structures, ways of being that emulate the world we want.

There is great potency in this context as it creates the ability to experience some of the new world that we want while still living in the hollowed shell of a decaying, oppressive society. And too, the dissonance between two worlds requires rigorous attention and care on the part of the team as well as humor and love. It is here that we begin to crack open the old and spill toward the new.

“When I dare to be powerful to use my strength in the service of my vision then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid.”

Audre Lorde

Approaches and Practices

So much of the focus of racial equity-based system change is on tools and frameworks. This tendency reflects the white dominant habit of overvaluing numerical data and the written word. While surveys, assessments, numerical analysis and the frameworks that outline how to apply them are valuable, they will not, in and of themselves, lead to intersectional racial equity let alone liberation. What will lead to equity is changing both what we do and how we be together. Assessing where an organization in terms of racial equity is the first tiny step and can be harmful if other steps don’t follow.

The Elements of Transformation

We have found that the most essential approaches to advancing intersectional race-equity systems change are those rooted in the elements of transformation toward liberation acting as the five fingers of one hand:

- Deep Equity & Liberation

- Complex Systems Change

- Leadership & Power Sharing

- Innerwork

- Multiple Ways of Knowing

What we are up to in our justice work boils down to equity and liberation whether we are talking about environmental justice, gender justice, educational access, or any of the social and economic harms resulting from the legacies of slavery and colonialism in the U.S. Advancing this kind of change IS complex systems change. In order to lead complex systems change, we must expand our understanding and expressions of leadership to embrace power-sharing and collaborative action. Leading together in this way requires innerwork, so we can be present for and resilient with change, and expanding how we know and what is considered wisdom in order to dislodge the dominance of white, western culture. This is individual and collective work. We have written extensively about this. For a deep dive, please read our blog on Practicing the Elements of a Liberating Ecosystem and earlier articles published in the Nonprofit Quarterly (NPQ): Pursuing Deep Equity, Cultivating Leaderful Ecosystems, Embedding Multiple Ways of Knowing, Influencing Complex Systems Change, and Centering Inner Work.

Equity-Focused Teams

In organizations and networks, particularly majority white and/or white dominant culture and multiracial/multicultural ones, any equity focused effort needs to be supported by an internal equity team—one that draws on the organizational diversity in terms of roles, experiences, expertise and identities. In order to advance equity, there needs to be an aligned and skilled group to shepherd change that has the credibility to champion emerging changes. Some of the qualities of equity team include:

- people committed to equity;

- people who have some lived experience of the effects of intersectional and systemic racism;

- people committed to the mission and vision of the organization;

- people who have either have the decision-making power and/or influence ability to advance change;

- people willing and able to commit to the time and effort equity efforts will require (note: the organization needs to be sure to make this focus and attention possible, e.g. this can not be an additional item added to people’s work expectations without removing other things);

- people able to hold confidentiality (share learning not other people’s information) and

- people able to engage in difficult conversations and see the potency of generative conflict

In contexts where Black and Indigenous people, wisdom, cultures are centered and organizations are rooted in a liberatory stance, the commitment to and experience with advancing racial equity exist across the organization and power is shared more broadly. In this context an equity team may or may not be necessary. Rather equity transformation efforts can be held in existing structures and team compositions. Racial equity coaching and consulting support in this context is even less about the doing and more about the being, tending to the complexities of transformational change in interracial teams and organizations while existing in a violent, toxic, and oppressive society.

Internal Skill Development

In all contexts, advancing intersectional racial equity requires that we develop and/or deepen our skills in being deeply present, loving, and human with one another. It means we need to lift one another out of survival states—where all energy is necessarily focused on getting our basic needs met—and cultivate the ability to be present to past and current suffering, giving voice to what has been unspeakable, entering conversations from a place of deep curiosity, and being willing to engage with difference—different perspectives, experiences, ways of making sense of the world. We do this because the change we seek actually requires all of us. It will not happen because of a few exceptional leaders. American exceptionalism is actually part of the knot that binds us in deeply inequitable ways.

Depending on their context, as outlined in the earlier section, and the existing experiences and expertise of different teams, new skills and/or muscles (as the nascent skill may actually exist it is just underutilized) will need to be developed. That said, there are some foundational skills and/or muscles needed to advance racial equity and the interdependent elements of a liberating ecosystem. They are:

- the ability to engage in generative conflict—actually embracing difference and the ways it can lead to conflict as a source of creativity and change;

- providing real-time affirmative and critical feedback on how we are impacting one another so that we can learn and grow;