MEASURING LOVE in the JOURNEY for JUSTICE

Below is the preface to this week's featured resource: Measuring Love in the Journey for Justice. Find the link to download this Brown paper at the end of this post.

MEASURING LOVE

Preface: A Sovereign Perspective

As this is a Brown—not white—Paper, we want to give some perspectives before you dig in. In a sovereign, self-determining perspective, we see Two Spirit people as sacred gifts. Children are treasured. Elders are respected and privileged. Womyn are beloved and respected and have power and voice. Fathers, sons, and boys are lifted up as the warriors, believers, and loyal friends that they are. Mothers, daughters, and girls are as valued as life itself, seen and treated as blessings. And all relations are sacred.

To be sovereign and free, our people need policies made of love, forgiveness, and connections.

As oppressed, exploited people of color in this work of social and racial justice, we have seen — and are seeing—children separated from their caregivers, caged in concentration camps. We are living in another era of the systemic denial of democratic civil rights. To be sovereign and free, our people need policies made of love, forgiveness, and connections. Our communities deserve health and educational equity; land and housing justice; economic independence; living wages (as in universal minimum income). Our people want restorative justice practices to replace punishment and lockup. Our communities want community organizing and advocacy, block by block. Our people need community controlled governance and accountability systems. We want civic leadership everywhere, as the right to vote goes with the rights to drive, assemble, drink, and travel.

This Brown Paper flips the script of what is acceptable as a “Paper” on its head. It is not a “formal,” research-based, finished product of the traditional type. It comes from the heart and is meant to be used—like love. It is meant to spark dialogue and provoke.

In it, we are asking ourselves, “Are we loving bravely enough?”

And “How much am I loving?” “What else I can do to be in community from a place of love?” and “How am I wielding power fused with love?”

These are the essential questions posed in our brown paper. We are excited to bring this out into the world to provoke, connect, and build with you.

We have so much to love. We love YOU because we know if you’re reading this paper, you know what it’s like to be powerless and not feel loved—and are working on bringing about more justice in the world.

We release our intentions into the universe. We want to know what your reactions are. We thank you for honoring us by your comments and discussion.

Spread your love. And, we know we are rising as one.

Download Measuring Love in the Journey for Justice HERE

Shiree Teng has worked in the social sector for 40+ years as a social and racial justice champion – as a front line organizer, network facilitator, capacity builder, grantmaker, and evaluator and learning partner. Shiree brings to her work a lifelong commitment to social change and a belief in the potential of groups of people coming together to create powerful solutions to entrenched social issues.

*After the Measuring Love Brown paper was released, Shiree's co-author was arrested on allegations of child molestation. She addresses this in a "Letter to Beloveds" - an excerpt from her next collaborative paper, Healing Love into Balance. (which will be highlighted at NW in the coming weeks.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Belonging to ourselves, each other, and the earth

From decolonization to... re-indigenization?

I’ve found myself increasingly interested in the promise of ‘embodiment’: the possibilities inherent in the seemingly simple act of being attuned to what our bodies are telling us. Thus far I’ve explored that concept primarily through the lens of the self, of the ‘I.’ But there’s more to it than that, something that feels powerful.

So today I want to explore the transformative potential of learning to sense and feel at three different levels: what in Building Belonging we call the levels of “I, We, World.” The promise of belonging is the promise of integration: it’s about belonging to ourselves, to each other, and to the earth.

“All transformation is linguistic”… and embodied?

This topic is especially hard to think and write about clearly because we lack the language. It’s difficult to conceptualize something if we can’t name it (an insight made famous in Betty Friedan’s discussion of “the problem that has no name.”) It was perhaps with this in mind that Peter Block provocatively wrote “All transformation is linguistic.”

I think he’s right… and the sentiment is incomplete. I do think the power of naming something is itself a transformative act: it allows us to see things in a new light, to understand an aspect of our experience that had thus far remained inaccessible. As Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote:

Language is the dwelling place of ideas that do not exist anywhere else. It is a prism through which to see the world.

But language is a starting point for transformation; it creates possibility. To realize that potential, however… requires embodiment.

This is the core insight of the emerging field of somatics, which deals with the “soma” (the Greek word for “body”). It’s at once an obvious and a radical idea: of course we move through the world in physical bodies, and of course those bodies inform our perceptions. And yet: Western culture tends to dismiss any forms of knowledge or information that are not “rational,” and emerging from the brain (I think, therefore I am). Indigenous cultures the world over have always held a more expansive view of human experience, talking instead of the heart, mind, body, and spirit. As Pat McCabe (Woman Stands Shining) notes,

The intellect is the least reliable way of knowing anything.

So I want to explore here (as always) the possibility of the both/and. Yes there is a power in naming something, in rendering a concept intelligible and accessible through words. And that’s not enough. There are other ways of knowing, feeling, and sensing… and it is these other ways that I want to explore today… at the level of I, We, and World. As MawuLisa Thomas Adeyemo said:

If we listen to our body, there is so much we can learn.

Belonging to ourselves: decolonization

There has been an emerging discourse in recent years about decolonization. There’s more there than I can unpack in this post, but the core concept is captured in the word itself: it is the antithesis to colonialism. It is a process of undoing, of unlearning… of practicing a different way of being.

Colonization is about conquest, growth, domination, enclosure, enforced scarcity, certitude about a singular way of being… it demands assimilation. Decolonization invites us to return to a world before colonization, to undo the ravages of the colonial mindset: to replace domination with partnership, growth with regeneration, conquest with harmony, scarcity with abundance… and embracing multiple ways of being. Decolonization invites a return to right relationship: with ourselves, each other, and the land on which we depend. We can understand colonization as a form of trauma at multiple levels. As Susan Raffo reminds us:

All trauma is collective, but we experience it individually.

This experience of trauma and fragmentation inspires resistance; humans are resilient, and we seek re-integration. Quoting Jacqui Alexander, the Gesturing Toward Decolonial Futures collective (amazing name!) puts it this way:

The material and psychic dismemberment and fragmentation created by colonialism also produce “a yearning for wholeness, often expressed as a yearning to belong, a yearning that is both material and existential, both psychic and physical.”

Yes. That’s it: a yearning for wholeness, for belonging. This is the desire animating the decolonial urge.

I’m coming to believe that the surest and swiftest path to decolonization is through embodiment, through learning (remembering) to feel and hear what our bodies are telling us. I was delighted to finally find the word for this last year: interoception describes our felt sense of our body’s internal states (hunger, anger, tightness in the chest, lump in the throat…). This is where most somatics work is done: at the level of the ‘I’ and our relationship to our own bodies. And in a cultural context that teaches us from our earliest ages to disregard and override what our bodies are telling us… it’s revolutionary work.

So here’s the idea I want to offer here: interoception (intentional embodiment) is one powerful way we can practice the art of decolonization. It is about reconnecting with ourselves, and orienting toward this truth: the body knows… if only we listen to it. There are many ways to practice: yoga, somatics itself, other forms of bodywork that invite deeper attunement to what our bodies are telling us.

Belonging to each other: cultural somatics?

Here’s another truth I’m coming to: all transformation is relational. If no one is an island… then surely our efforts to transform must start from that premise? Here’s Parker Palmer:

If we are willing to embrace the challenge of becoming whole, we cannot embrace it alone—at least, not for long: we need trustworthy relationships to sustain us, tenacious communities of support, to sustain the journey toward an undivided life. Taking an inner journey toward rejoining soul and role requires a rare but real form of community that I call a “circle of trust.”

Here again words fail us. I’ve been looking for the word that describes sensing into a collective: picking up the vibe in a room, feeling each other without touching. We all do it all the time… how can there not be a word for it? If you know the word I’m looking for, please share! Other languages besides English also welcome (not surprising that the colonizers lack words for a decolonial construct…)

There are some concepts that get close: “co-regulation” describes the idea that we synch to each other’s moods. But the concept I find most enticing here I first encountered through Tada Hozumi in their exploration of “cultural somatics.” Here’s how Prentis Hemphill puts it:

Culture is a place to tend to our collective embodiment.

Basically, the idea is that we have a collective “soma”: our individual bodies are part of a broader whole that we can feel and sense, and which exerts an influence on us. I think we all know this to be true (at least the idea that we are subtly influenced by those around us), but we don’t often acknowledge that reality. As Charlotte Rose observed:

We are animal bodies near other animal bodies. And we influence and impact each other all the time.

I’m not sure exactly what good practices are here for learning how to practice collective embodiment. I feel confident in echoing the refrain that transformation is inherently relational, and therefore the first thing we must do is find a community within which to practice. Brené Brown had a beautiful line here:

The key to building a true belonging practice is maintaining our belief in inextricable human connection. That connection—the spirit that flows between us and every other human in the world—is not something that can be broken; however, our belief in the connection is constantly tested and repeatedly severed.

I would go farther: it’s both a belief and an opportunity to practice in community. Skillful facilitators can help us; Ria Baeck talks of “collective presencing” as one methodology, but honestly this remains an area of inquiry for me. How can we learn to sense, feel, and act on collective embodied intelligence?

Belonging to the world: re-indigenization?

Our relationship to land is a whole post in its own right… I just want to touch on one concept here. I believe that disconnection is core to our current crises, and that re-integrating is a huge piece of the solution. Our loss of connection to land remains an open wound that we haven’t addressed… and I don’t see a way forward that doesn’t involve repairing that wound.

Indigeneity at its core is about belonging to land: it’s about living in right reciprocal relationship with the earth. Most of us have lost that. Derek Rasmussen had a beautiful article for YES! Magazine where he contended that we (White people in western cultures in particular, but to some extent all of us) are the first non-indigenous civilization in the history of the planet. These different forms of disconnection are of course related: to be separated from land is also to be disconnected from people, from our ancestry, and therefore from ourselves. Gibran Rivera observed:

We are the first generation to steal from our descendants, because we have forgotten our ancestors.

It affects all of us, for by now nearly all of us have been forcibly displaced by factors beyond our control. As Simone Weil wrote in her classic The Need for Roots: “Whoever is uprooted himself uproots others.” This is not to erase agency or accountability, but to acknowledge a long history of colonization (and trauma) that underlies its contemporary manifestations. Wendsler Nosie, a spiritual leader to the Apache living on San Carlos Apache reservation, explains:

When native people talk about decolonizing, you know everybody has to become decolonized. Everybody has to wake up to what is happening. White people are the oldest people that are colonized, then the rest of us we come after that. We’re all blind from being colonized.

The idea I’m trying to convey here is that the earth (the entire planet as a whole, but more specifically the particular land where we find ourselves) has its own “soma” that we feel, sense, and respond to. This is literally true, not a matter of spiritual conjecture. Here’s David Abram:

The body is always in a subtle interaction and engagement with the large vast body of the Earth itself.

Increasingly scientists are “discovering” what indigenous people have long acknowledged: we are inextricably connected. Greater Good Science Center recently ran a podcast on why we enjoy nature exploring what happens in our brains as we interact with the natural world… it is literally restorative for our brains and bodies. Anyone who has breathed the smell of a forest after a rain can attest to a truth science is now confirming. Robin Wall Kimmerer summarizes the research:

Breathing in the scent of Mother Earth stimulates the release of the hormone oxytocin, the same chemical that promotes bonding between mother and child.

As any gardener or farmer can attest, we all know this, deep in our bodies. We just don’t often stop to acknowledge that fact. I was reading the children’s classic Heidi with my 6-year-old where the narrator observes:

It is good to be on the mountain. Body and soul get well, and life is happy again.

Healing the land is healing ourselves

I found myself nodding along as Kim Smith, an indigenous Diné organizer explained that violence to the land is violence to ourselves. This landed with the ring of truth: it explains the visceral feeling I get when I see a clearcut in an otherwise majestic forest, or oil-soaked animals washed up on the shore after an oil spill. How else to describe that sensation if not pain? Loss?

But this too points the way forward, for the inverse is also true. As Shane Bernardo reminds us:

In healing the land we are healing ourselves, and in healing ourselves we are healing our ancestors.

But there is a sequencing here. As Glennon Doyle wrote in Untamed: “nothing can be healed if it’s not sensed first.” Channeling trauma researcher Bessel van der Kolk, Maria Popova explains:

In order to change, people need to become aware of their sensations and the way that their bodies interact with the world around them.

Again, words fail us. I believe re-indigenization is the process, but what is the name for the practice, for the act of sensing/feeling our interdependence with the earth? I just finished reading Black futurist N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, and she introduces the word “sessing” to describe this (makes me think of how animals can detect earthquakes before humans… perhaps we too could cultivate that skill?)

The closest I’ve been able to find outside the world of sci-fi is the concept of “entrainment”: the notion that bodies (including objects we would consider inanimate!) have a tendency to synchronize when in contact over time.

Names are the way humans build relationship

I want to close by offering two domains of practice, returning to our theme of connecting the transformative power of language and embodiment. The first shift is linguistic: to recognize the earth and non-human life as beings worthy of respect and consideration. Here’s Ursula Le Guin:

One way to stop seeing trees, or rivers, or hills, only as 'natural resources,' is to class them as fellow beings—kinfolk. I guess I'm trying to subjectify the universe, because look where objectifying it has gotten us.

Robin Wall Kimmerer has made this a key feature of her writing and work, even offering us a pronoun echoing Le Guin: ‘ki’ (as a singular form of the plural ‘kin,’ but also a play on the French pronoun ‘qui,’ meaning ‘who’). She explains:

Names are the way we humans build relationship, not only with each other but with the living world.

“What the hands do, the heart learns”

I first encountered this concept via Movement Generation, as a welcome reminder of how humans learn and transform. Through embodied action. Katherine Gibson and Julie Graham put it well:

If to change ourselves is to change our worlds, and the relation is reciprocal, then the project of history making is never a distant one but always right here, on the borders of our sensing, thinking, feeling, moving bodies.

So… how to do that? Arawana Hayashi, creator of the art of Social Presencing Theater, offers a practice called “Body Knowing as a Vehicle for Change”:

It is an invitation to feel the connection, naturally present, between our body and the earth body.

David Abram offers another prescription:

Falling in love with the more than human earth is the deepest medicine we have available.

I’ve been ruminating on this post for a while, and struggling to find time (and words!) to convey the concepts that feel so connected to me. I’d love to know what resonates, and if you’re finding terms/ways to practice connecting yourself, each other, and the world.

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at building belonging

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

People Stitching Earth | Oppression, Healing, Liberation, and Navigating the Terrain In Between

When we made it back home, back over those curved roads

that wind through the city of peace, we stopped at the

doorway of dusk as it opened to our homelands.

We gave thanks for the story, for all parts of the story

because it was by the light of those challenges we knew

ourselves—

We asked for forgiveness.

We laid down our burdens next to each other.Joy Harjo, “Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings,” An American Sunrise

Origin Story

The first beings were not humans or animals or even plants. The first beings were river, rock, lava, and sky. Later came plants, then animals, then last of all, came two-leggeds who became easily lost and had to learn again and again in order to remember their way. This is a story of that journey—one that started in harmony and abundance and has been transformed by settler colonialism, enslavement, and their aftermath: patriarchy, extractive capitalism, collective violence against aki, the earth, and all her inhabitants. The resulting interlocking systems of oppression choke lungs, poison waters, exterminate life, and obscure the sun.

This is not a story about re-making a fictional ideal past. Harmony, in narrative or music does not preclude disagreement or conflict. This is a story about some of the ways we can return to who we truly are and how we are meant to be in right relation to each other and all beings, mortal and immortal, sentient, interdependent, free.

The Journey

During this time of the great sickness—a time of tyranny, violence and greed—people have been harmed deeply by the practices of oppression: disconnection from source (a higher power and understanding of the world as greater than ourselves such as through spiritual, natural, cultural, ancestral, and/or creative practice); dissociation from our physical bodies; distancing from our emotions; and distortion of our stories.1 Some days the effects are overwhelming; the sickness is life threatening. Some days—with rest and soup, with love and community care—there are moments of shared understanding, connection, and transformational shifts in understanding and behavior.

Beyond rest and community care, what makes these moments possible, and the potential for such moments to multiply exponentially, is not one but many things, things that operate across the dimensions of personal, interpersonal, organizational/institutional, and societal/social systems.2 For those of us working as racial equity change makers—whether as internal or external coaches and consultants, including those who work in intersectional roles as healers, artists, and liberation practitioners—there is a familiar route that embraces organic twists and turns and yields movement in the right direction.

The current emphasis in our field on trainings, assessments, and curriculum—which are all good and necessary components of intersectional racial equity and can be catalytic, if used in their full potentiality—are too often leading people into thorny thickets and near cliff edges where they give up, abandoning the journey, or worse, go back from whence they came. This is not to say that these entry points are not useful ways of understanding our contexts and our own behavior in them, but they are insufficient in supporting the integration and embodiment of new ways of being, understanding, and engaging with the world. When we practice the elements of a liberating ecosystem, we enable the seeds of training and assessments to meet the nutrients and environments needed for them to take root and grow.

There are many ways to traverse the multi-faceted and challenging terrain created by the delusion of white supremacy, but overall the best possible paths are moving in the direction of intersectional racial equity that engages people and systems in practices of healing and liberation. We liken this process to a journey in the woods. There are a number of recognizable clearings or places that support visibility and understanding. And it is in these clearings that clarity, commitment, and learning is possible.

Unlike rational and determinist approaches to intersectional racial equity—ones that center assessment tools, analytical instruments, and pre-defined linear processes—we have found that these pathways are open-ended enough to support opportunities to digest learning and engage in intentional action, through which we can engage in cycles of feedback and reflection to support unlearning white supremacy and re-membering our practices of interdependence, mutuality, and stewardship.

Complexity and Justice-Oriented Change

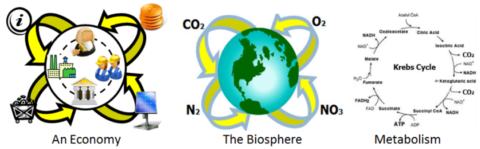

Advancing racial equity is complex systems change, and while working in complexity there are very, very few, if ever, “best practices”. There are more good practices and most situations require emergent and adaptive practices.

Some characteristics of complexity—as outlined by David Snowden and Mary Boone3—are contexts where:

- “Large numbers of interacting elements are involved.

- The interactions are nonlinear, and minor changes can produce disproportionately major consequences.

- The system is dynamic, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and solutions can’t be imposed; rather, they arise from the circumstances. This is frequently referred to as emergence.

- The system has a history, and the past is integrated with the present; the elements evolve with one another and with the environment; and evolution is irreversible.

- Though a complex system may, in retrospect, appear to be ordered and predictable [eg. history], hindsight does not lead to foresight because the external conditions and systems constantly change.

- Unlike in ordered systems (where the system constrains the agents), or chaotic systems (where there are no constraints), in a complex system the agents and the system constrain one another, especially over time. This means that we cannot forecast or predict what will happen.”

This articulation of the characteristics of complex systems is helpful. And too, it is important to recognize that indigenous cosmologies and teachings—particularly those from the Americas and Africa—situate a complex world in which binaries and closed systems do not exist. The cynefin model, the sense-making tool that visually represents Snowden’s complexity theory, is itself from native Welsh principles and language. The word cynefin means roughly “place of our multiple belongings.”

The metaphor of a path or route, one that is organic and emergent, has the flexibility to hold the complex nature of the change we are seeking toward equity and liberation. When traveled with practices of power and leadership sharing, committed attention to innerwork, and embracing multiple ways of knowing, we live in iterations of change that both begin to prefigure the world we want and create the necessary conditions for advancing liberation in the world we are currently living in.

Charting the Terrain

Clearing One – A Reflective Pool

There are many ways to gain an understanding of where an organization and team is in terms of living into intersectional racial equity. Many equity practitioners use written or online assessments. Others hold interviews or focus groups. Some establish storytelling circles or work together to develop murals or other forms of visual narrative. Some use a mix of quantitative and qualitative (including artistic) approaches. Regardless of the approach and the associated tools and practices, the purpose is to get a complex, aggregate picture of what is, a picture of the terrain that is so much more than an organizational map. It is a layering of perspectives that helps the organization and its partners gain some sense of the contexts and conditions comprising the culture and lived experiences of people in the organization or network.

Clearing Two – A Rocky Outcrop

Once a picture of the terrain is made visible, another clearing presents itself. This rocky outcrop is a place where everyone is able to see the full and discrete snapshots of the organization and participate in a shared meaning-making process about what these snapshots might say about the team and the organization. However, collective sense-making requires some shared understanding of the current and historical structures, strategies, and belief systems that benefit some people at the expense of others. This is a juncture in the journey where indepth, whole-system conversations are crucial to restore the very real stories of settler colonialism, enslavement, genocide, wage theft, and extractive capitalism that have largely been disappeared from and or greatly distorted in our education systems. Building on these understandings, teams can also develop a shared understanding of how the continuing impacts of these legacies and other ongoing systems of oppression and inequity interact to perpetuate the manifestations of inequity in our lives and organizations. This discordant recognition is fundamental to the path.

Disagreements about what it all means and why—this generative tension—is what pushes teams and organizations toward deeper understanding. How is it that our shared language is so full of references to militaristic strategies that supported western expansion, manifest destiny and Native genocide? And how is it that the end of the enslavement of African and then African American people has done little to shift the fundamental economic, health, educational—insert just about anything here—disparities between whites and Blacks? The actual questions that teams grapple with have a lot to do with who’s on the team, their lived, racialized experiences, and the depth of their power analysis.

What matters is that teams are moving towards a shared understanding that interrupting current, intersectional racial inequities isn’t possible without having a depth of knowledge about historical inequities and the practices and systems that support their perpetuation. In this rocky outcrop, teams will often read, attend workshops and trainings, participate in caucus or affinity groups to support interrupting internalized oppression and internalized privilege. This learning journey is essential and what it entails depends on who is on the journey together. Among people of similar racialized identities it may mean grappling with global colonialism and the ways that it has impacted different peoples and different families’ histories. Healing often becomes a central focus, calling in ritual and ceremony to support the processing and release of past and present trauma.

This can be a difficult time in an organization. The fallacies that held the team together have been stripped away. But nothing new is yet in its place. It is a time for care and humility. It is a time to support the ingestion and digestion of the pervasive, corrosive presence of racial equity, making space for the restoration of our collective humanity within and across all racialized groups. It is a time for reconnecting to source, reengaging our bodies, reclaiming our emotions, and reweaving the fullness of our stories. This can mean a necessary, intentional, and sometimes scary unmooring in the day-to-day. And too, it is an opportunity for people to show up differently and build the muscle and heart necessary to get to the next evolution in the process. It requires cultivation of courage, humility, and room for risk-taking, as well as tools supporting accountability and collective tending to harm. This place demands space and time. This place requires more of us than we have sometimes been able to give. There is a necessary clarity that comes from such disruptions. As Norma Wong says, “transformation requires agency.” Some people may, in fact, choose not to move with their team or organization. And that is part of the journey too.

Clearing Three – A Sudden Vista

Through a commitment to authenticity and rigor—and doing the necessary work of deepening our understandings of historical and current conditions that affect our individual and collective experiences—we come to a sudden vista, an opening in our capacity to see a different future. A future where we all have the ability to thrive.

It is here that a visioning process can truly expand our shared picture of a liberated and liberatory future. From this vision, we can outline the values and principles that guide how we be with each other in liberating ways and define some key short term and long term transformation efforts, arriving together at those aspects of the organization that, if transformed, would enable people to experience an actual taste of equity in the immediate term while working on efforts to change the organization overall in the long term.

What we are creating is not new, yet it can be wholly unfamiliar. However, we have everything we need to make this visionary future possible. It simply requires courage, imagination, and the willingness to move as if we have one foot firmly on land and the other submerged in the tumultuous and profuse waters of the sea.4

Clearing Four – A River Flows

Once the vision, values, hopes, and dreams, the team can start developing some focused priorities and goals and the implementation effort begins to flow. But equity transformations are always a mix of inspirational visions and more tangible decisions and practices. Weaving across the two is the art of advancing complex systems change in which we are developing experiments across the organization’s functions and programs. Or it might be one or two short and long term efforts from which the team and organization is continuing to learn and to refine in ongoing cycles of reflection and growth. What matters is that the effort is continuous and fluid, and that the fluidity takes into account boulders, logs, beavers, otters as obstructions are also natural innovations to the existing ecosystems. Throughout this process, the team is meeting current capacity and emerging circumstances in ways in which both the vision of equity and the realization of equity are contiguous tributaries in the river’s powerful flow.

Context Affects the Terrain

While we are all swimming in the torrential waters of racial inequity and other intersectional forms of oppression, we are affected differently. Some are buoyed by floatation devices. Some are carried along by speedboats. Others are fighting to keep their airways above the surface of the water. The same is true for leaders, teams, organizations, and networks.

To make sense of these differing contexts—at all of the levels of racial oppression including internalized, interpersonal, institutional and systemic—we are going to describe differing approaches based on where different types of individuals, teams, organizations and networks live along a white dominant-to-liberatory spectrum: 1) White Supremacy Culture, 2) Multicultural Stance, and 3) Pro Black and Indigenous.

While such classification efforts are inherently overly simplistic, there is sufficient value in outlining different approaches based on these categories, contexts and associated conditions.

1) White Supremacy Culture (aka “The Delusion of White Supremacy & the Culture that Upholds It”)

In an organizational culture of white supremacy, organizations are habituated to working in ways that uphold the delusion of white supremacy whether intentionally or not. These cultural practices have been laid out in the work of Tema Okun and continue to be deepened by other racial equity practitioners. Initially identified as thirteen habits, the framework has evolved to include nuanced descriptions of behaviors that reify inequity, transactional relationships, and oppressive power structures. These cultural habits are exemplified by valuing perfectionism, individualism, fear, right to comfort, competition, urgency—and drive most organizational decisions and overall organizational culture in white dominant organizations.

These organizations are most often:

- White led and/or have a history of white leadership and predominately white staff (not always white-led; may include people of multiple races at various levels of the system but not in large numbers in leadership and if so, not for very long);

- Equity focus is on diversity, equity & inclusion (DEI), with an emphasis on diversity; and

- People exhibit and experience disconnection from source (a higher power and understanding of the world as greater than ourselves such as through spiritual, natural, cultural, ancestral, and/or creative practice); dissociation from their bodies; distancing from their emotions; and distortion of their stories.5

- There are also historically people of color-led organizations that operate predominantly in this fashion; most often they are in areas of work that are deeply steeped in white supremacy culture such as some legal, policy, research, philanthropic and merit-based youth-serving organizations.

Deep equity work in this context focuses on making visible the ways in which white supremacist ways of being and doing are operating as an uninterrogated norm which serves to reify white leadership and the myth of white supremacy and/or undermine the wisdom, gifts, and value of BIPOC people. Organizations in this category are often set up to support the learning, comfort, safety, and power of those in leadership and particularly white leaders. Change processes can unintentionally replicate these patterns at the expense of native people and people of color.

Racial equity change makers will often focus on cultivating equity-based awareness and understanding with white leaders in the system to ready them and thus the organization for deeper equity work. This aspect of the change effort can be very depleting for staff of color in every level of positional power as well as for all staff with less positional power within the system. The tax of this effort is in direct relationship to white leaders willingness, courage and capacity to develop a baseline understanding of structural racism and intersectional elements of oppression. If leaders are resistant to deepening their awareness and/or actively suppressed learning then little progress can be made without developing alternate leadership structures to support the organization in its evolution.

2) Multicultural Stance

In multiracial/multicultural contexts, organizations tend to exhibit characteristics of both white supremacy culture and what Okun would call “antidotes.” In this instance, an organization might be more recently led by people of color and/or have significant numbers of people of color throughout the organization including on the leadership team. In this context, the racial equity and liberation (REAL) work is more often focused on equity, which is made possible by the fact that people in the organization have a solid understanding of structural racism and intersectional elements of oppression.

The organizations are often actively seeking to disrupt the habits of white supremacy culture and people have more shared practice of expressing the harm caused both within and beyond the organization. However, having not yet fully developed the muscles of an equity-based organizational culture, the organization and its leaders will often default to white supremacist ways of working in urgency or in high-stakes decision-making, for example relying on positional power instead of embracing wisdom, experience, and skill-sets from multiple people in the system and therefore have trouble implementing equity-based systems change internally.

While all racial equity work needs to center healing, the work in multiracial/multicultural contexts often necessitates a focus on healing at intra-personal, interpersonal, and organizational levels simultaneously in order to create the needed conditions for equity-based systems change. REAL change in this context is about unlearning our beliefs and related actions as a result of internalized oppression and our complicity with white supremacy as people of color. For white people in all contexts, the work is about interrogating internalized white supremacy so that long standing ways of maintaining privilege are dislodged, making space for new ways of living and being that don’t center whiteness and the power it exerts in explicit and implicit ways. Specifically, in multiracial/multicultural contexts, white people tend to have more systems based understanding but are often still struggling to recognize that impact is not exclusively the result of individual intention. The arc of learning in this context is to develop a more complex understanding of the relationship between “it’s all my fault” and “it’s all the systems fault” in order to recognize that—because of race, power and privilege—they are both simultaneously true. In order to live into this complexity, it calls on all of us to begin to embody new ways of being.

3) Pro Black and Indigenous

In contexts where Black and Indigenous people, wisdom, and cultures are centered, organizations are led and predominately composed of multi-identitied or single-race identified Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) that have done work to address anti-blackness and anti-indigenity as a collective. The organizational vision and mission are rooted in social justice and liberation. People exhibit greater connection to source. They are in touch with the wisdom of their bodies and their emotions and are resourced by and able to be in whole and simultaneous stories. The focus of the work is beyond equity toward liberation and sovereignty.

In this context, healing work (individual and collective) is both foundational and ongoing as the organizational culture exists in a wider, toxic, and systemically oppressive society. In addition to engaging in healing and liberating practices, liberation requires continuing to address inequities; building our collective muscles for engaging in generative conflict, giving and receiving feedback, and holding each other in loving accountability; in addition to developing and evolving more equitable power structures and practices. It takes collective care and courage to embody and enact the systems, structures, ways of being that emulate the world we want.

There is great potency in this context as it creates the ability to experience some of the new world that we want while still living in the hollowed shell of a decaying, oppressive society. And too, the dissonance between two worlds requires rigorous attention and care on the part of the team as well as humor and love. It is here that we begin to crack open the old and spill toward the new.

“When I dare to be powerful to use my strength in the service of my vision then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid.”

Audre Lorde

Approaches and Practices

So much of the focus of racial equity-based system change is on tools and frameworks. This tendency reflects the white dominant habit of overvaluing numerical data and the written word. While surveys, assessments, numerical analysis and the frameworks that outline how to apply them are valuable, they will not, in and of themselves, lead to intersectional racial equity let alone liberation. What will lead to equity is changing both what we do and how we be together. Assessing where an organization in terms of racial equity is the first tiny step and can be harmful if other steps don’t follow.

The Elements of Transformation

We have found that the most essential approaches to advancing intersectional race-equity systems change are those rooted in the elements of transformation toward liberation acting as the five fingers of one hand:

- Deep Equity & Liberation

- Complex Systems Change

- Leadership & Power Sharing

- Innerwork

- Multiple Ways of Knowing

What we are up to in our justice work boils down to equity and liberation whether we are talking about environmental justice, gender justice, educational access, or any of the social and economic harms resulting from the legacies of slavery and colonialism in the U.S. Advancing this kind of change IS complex systems change. In order to lead complex systems change, we must expand our understanding and expressions of leadership to embrace power-sharing and collaborative action. Leading together in this way requires innerwork, so we can be present for and resilient with change, and expanding how we know and what is considered wisdom in order to dislodge the dominance of white, western culture. This is individual and collective work. We have written extensively about this. For a deep dive, please read our blog on Practicing the Elements of a Liberating Ecosystem and earlier articles published in the Nonprofit Quarterly (NPQ): Pursuing Deep Equity, Cultivating Leaderful Ecosystems, Embedding Multiple Ways of Knowing, Influencing Complex Systems Change, and Centering Inner Work.

Equity-Focused Teams

In organizations and networks, particularly majority white and/or white dominant culture and multiracial/multicultural ones, any equity focused effort needs to be supported by an internal equity team—one that draws on the organizational diversity in terms of roles, experiences, expertise and identities. In order to advance equity, there needs to be an aligned and skilled group to shepherd change that has the credibility to champion emerging changes. Some of the qualities of equity team include:

- people committed to equity;

- people who have some lived experience of the effects of intersectional and systemic racism;

- people committed to the mission and vision of the organization;

- people who have either have the decision-making power and/or influence ability to advance change;

- people willing and able to commit to the time and effort equity efforts will require (note: the organization needs to be sure to make this focus and attention possible, e.g. this can not be an additional item added to people’s work expectations without removing other things);

- people able to hold confidentiality (share learning not other people’s information) and

- people able to engage in difficult conversations and see the potency of generative conflict

In contexts where Black and Indigenous people, wisdom, cultures are centered and organizations are rooted in a liberatory stance, the commitment to and experience with advancing racial equity exist across the organization and power is shared more broadly. In this context an equity team may or may not be necessary. Rather equity transformation efforts can be held in existing structures and team compositions. Racial equity coaching and consulting support in this context is even less about the doing and more about the being, tending to the complexities of transformational change in interracial teams and organizations while existing in a violent, toxic, and oppressive society.

Internal Skill Development

In all contexts, advancing intersectional racial equity requires that we develop and/or deepen our skills in being deeply present, loving, and human with one another. It means we need to lift one another out of survival states—where all energy is necessarily focused on getting our basic needs met—and cultivate the ability to be present to past and current suffering, giving voice to what has been unspeakable, entering conversations from a place of deep curiosity, and being willing to engage with difference—different perspectives, experiences, ways of making sense of the world. We do this because the change we seek actually requires all of us. It will not happen because of a few exceptional leaders. American exceptionalism is actually part of the knot that binds us in deeply inequitable ways.

Depending on their context, as outlined in the earlier section, and the existing experiences and expertise of different teams, new skills and/or muscles (as the nascent skill may actually exist it is just underutilized) will need to be developed. That said, there are some foundational skills and/or muscles needed to advance racial equity and the interdependent elements of a liberating ecosystem. They are:

- the ability to engage in generative conflict—actually embracing difference and the ways it can lead to conflict as a source of creativity and change;

- providing real-time affirmative and critical feedback on how we are impacting one another so that we can learn and grow;

- recognizing that organizations, leaders, teams and networks need supportive structures and practices to survive in all times and most certainly to thrive during equity change efforts so be sure to get your foundation set before building something new; and

- holding loving accountability with one another – “the practice of loving accountability consists of honest and authentic communication, vulnerability, and the willingness to hold each other accountable for our impacts—beyond just words. If a collective value or guiding principle is repeatedly violated by someone, and no amount of communication and support can interrupt it, then loving accountability instructs us in employing meaningful consequences—not as punishment but rather as ensuring the health of the collective through meaningful boundaries.”6

Depth of Engagement

Any authentic, intentional and focused effort to advance intersectional racial equity has the potential to lead to transformational change. Such change could be evidenced by significantly increased understanding of systemic racism and the ways internalized supremacy is playing out in a white leader’s priorities and decision-making. Transformational change could look like a BIPOC team’s success in deepening its generative conflict muscles and being able to really unpack unspoken assumptions and internalized oppression in order to create new ways of advancing its vision and mission that supports the team in being and acting from liberation.

There is no “right approach” to support equity-based systems change. Rather there are necessary nutrients to ensure such an effort will seed, root and flourish. These nutrients are similar whether we are providing one on one coaching, team facilitation and support, or an organization-wide equity change effort. While all plants require differing amounts of sun, water, warmth, all require the fundamental macronutrients of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and potassium.

- Clear sense of purpose of and strong commitment to equity effort and its alignment with vision, mission and strategies;

- Willingness to let go of existing practices, structures and approaches and experiment with new ways of being and doing in order to change, learn and grow;

- A recognition that the wound of intersectional racism is still festering and any effort to heal and transform it brings with it the possibility of new injuries, discomfort, alternating periods of remission and acute illness and requires an enduring commitment to stay the course.

As individuals and teams evolve their application and wisdom of intersectional race equity and liberation, there are some frequent markers of understanding that mark this transformation. We draw these from some of the components of Jay McTighe’s and Grant Wiggins’ Understanding by Design framework.7

Perspective

Regardless of the context they are in, individuals and teams are able to articulate and apply the importance of race equity work in their day to day intentions, priorities, and decision making.

Empathy

In all contexts, individuals and teams are deepening their capacity to listen and see and feel things from different points of view and honor the lived experiences and perspectives of one another all while moving toward equity and liberation.

Self and Group Knowledge

People demonstrate a recognition and ability to grapple with their biases, triggers, and self perceptions in order to deepen their own and the team’s capacity for equity-based systems change.

These markers reflect some of those outlined in the modes of the Liberatory Design8 cycle, although those modes are stages of a process and what is being outlined here are markers of understanding, how you might know things are shifting in meaningful ways. Nonetheless, Liberatory Design provides an integrative approach—weaving across design thinking, complex systems change, and racial equity— and serves as another way of thinking about cognitive and behavioral approaches to change rooted in experimentation.

Moving through an Unfamiliar Present Makes Possible an Equitable and Liberatory Future

To live as if. It is not easy. Inner work and our cultivation of the capacity to be present, to see what is, to be part of the rapid, long and slow process of evolution, revolution, to breathe through it all is so necessary. Throughout this work we will dance and sometimes stumble and fall. Our cores must be both strong and flexible; and it takes all of us to reach our appendages toward each other, to lift one another up.

The world depends on us. Race equity and liberation (REAL) work gets us closer to holding each other in a field of love, from which place so many of the ills of the world are healed. As Paula Gunn Allen writes in Grandmother’s of the Light:

“It is said at the time of the beginning, the Goddess will return in the fullness of her being. It is said that the Mother of All and Everything, the Grandmother of the Sun and the Dawn, will return to her children and with her will come harmony, peace and the healing of the world. It is said the time is coming. Soon.”

We are here to turn the wheel toward a new beginning. One in which all of her children are free.

Collage credit: Naima Yael Tokunow

Originally published at Change Elemental

Elissa Sloan Perry (any pronouns used with respect) is of African and Mississippi Choctaw descent, hails from Missouri, and is a 30-year resident of California. She supports people with a vision for an interdependently thriving people and planet to be better in what they do. Elissa joined Change Elemental in 2013 as the Program Catalyst for the Network Leadership Innovation Lab, became CoDirector in 2015, and transitioned to the Leadership Hub in 2021.

Aja Couchois Duncan (she/her/we) is a San Francisco Bay Area-based leadership coach, organizational capacity builder, and learning and strategy consultant of Ojibwe, French, and Scottish descent. A Senior Consultant with Change Elemental, Aja has worked for 20 years in the areas of leadership, equity, and learning.

1 This framework for understanding the ways oppression separates us comes from the profound and inspiring work of Monica Dennis.

2From the work of Camara Phyllis Jones, “The American Journal of Public Health,” Levels of Racism: A Theoretic Framework and a Gardener’s Tale 90, no. 8 (August 2000): pp. 1212-1215, https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.35.12.1319, and john a. powell, “Structural Racism: Building on the Insights of John Calmore,” North Carolina Law Review 86 (2007): pp. 791-816.j

3David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making,” Harvard Business Review, November 2007, pp. 1-9, https://doi.org/https://www.systemswisdom.com/sites/default/files/Snowdon-and-Boone-A-Leader’s-Framework-for-Decision-Making_0.pdf.

4“one foot in the water / one foot in the sand is where I hear the best.” Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2020).

5 This framework for understanding the ways oppression separates us comes from the profound and inspiring work of Monica Dennis.

6Aja Couchois Duncan and Kad Smith, “The Liberatory World We Want to Create: Loving Accountability and the Limitations of Cancel Culture,” NonProfit Quarterly, May 19, 2022, https://doi.org/https://nonprofitquarterly.org/the-liberatory-world-we-want-to-create-loving-accountability-and-the-limitations-of-cancel-culture/?utm_content=208660872&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin&hss_channel=lcp-542508.

7David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making,” Harvard Business Review, November 2007, pp. 1-9, https://doi.org/https://www.systemswisdom.com/sites/default/files/Snowdon-and-Boone-A-Leader’s-Framework-for-Decision-Making_0.pdf.

8“Introduction to Liberatory Design,” National Equity Project, https://www.nationalequityproject.org/frameworks/liberatory-design.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

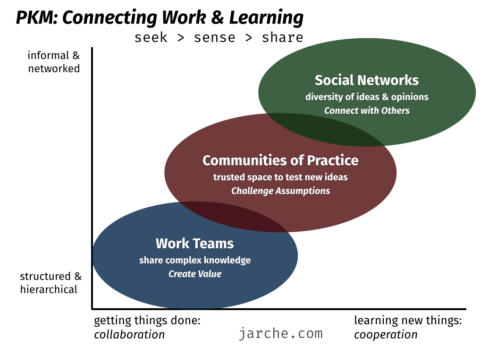

Networks: Resourcing Relationships and Interdependence for an Equitable Future Now

Networks for Equity and Systems Change

The events of the past year have made clear what many in and outside of philanthropy already knew: that equality in resource distribution is not equity, that much of what was thought impossible to change – telework policies, reporting requirements, fiduciary responsibilities – is suddenly possible, that what we need to shift big systems is interdependence (not codependence), and that what is needed for this shift to happen begins with strengthening our relationships with one another – as individuals, organizations, and communities.

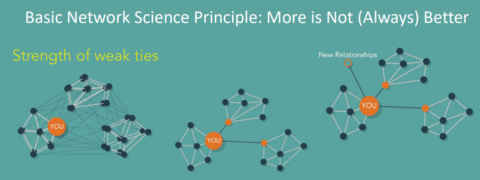

Networks offer a structure for linking people and groups of people with a shared vision and shared values to build and strengthen the relationships necessary to shift big systems. By offering us opportunities to work together in ways that challenge us to build different understandings of and relationships to power and to each other, we are able to move in more interdependent and interconnected ways.

Many individuals and organizations – particularly those rooted in Black and Native communities, queer communities, and immigrant communities – have experience working in networks both rooted in and working to advance equity and justice yet are often not sufficiently resourced for this work. Other entities, including many funders, are bringing increased attention and resources to working in this way and yet these many groups that are poised to resource networks are still just learning about how to do so in ways that align with equity and manage disproportionate power dynamics.

In this moment of possibility for reimaging big systems to live our imagined future of love, dignity, and justice now, we are sharing some learning from a late-2019 gathering of nearly 70 network funders, practitioners, and participants about how network practitioners and some funders are nourishing and growing networks for equity and systems change.

An Experiential and Embodied Approach to Learning in Networks

The Networks for Equitable Systems Change gathering was co-created in partnership with Change Elemental, Uma Viswanathan and Matt Pierce at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and a design team of network practitioners including Allen Kwabena Frimpong, Aisha Shillingford, Marissa Tirona, Robin Katcher, and Deborah Meehan. The group came together to engage with practices for building, resourcing, and sustaining networks. Together, we set out to learn about the following questions:

- How have funders and other organizations worked together in networks that promote equity and systems change?

- What are the barriers to resourcing networks for equitable systems change and what would it take to shift those barriers?

- What is the personal work and way of being needed to fully engage in networks, equity and systems change?

While desk research and interviews can be useful learning tools, we decided to take an experiential and embodied approach to learning about our questions. By bringing convening participants into the experience of network building in real time, we were able to create shared experiences that led to shared understanding about what it takes to build and sustain networks that can shift systems.

We can’t shift systems when we’re only touching one part of the elephant. We need spaces where the whole ecosystem comes together, bringing various perspectives that can give us a picture of the whole. Rather than host separate conversations with funders, intermediaries, and grassroots organizations, the gathering brought together many parts of network ecosystems to discuss how folks were experiencing power sharing within networks.

Below are some of the ways the experiential design of the convening – in addition to the deep expertise and knowledge that participants brought to bear – helped co-create our elephant and answer some initial questions about networks…

We Challenged Dominant Ways of Building Alignment through Rigid Frameworks and Definitions and Instead Reached Shared Understanding with Storytelling

Through experiential learning and storytelling, convening participants aligned on shared definitions for what we mean by a network as well as successful practices for building, sustaining, and resourcing networks.

With our design team, we co-created a learning network that engaged people with different access to resources, different kinds of power, and different experiences and roles in networks. We were concerned about bringing so many different folks together to talk about networks when we all were coming in with these different experiences, definitions, etc. We faced the same pressure points that networks face: how do we distribute resources across this group and compensate people for their time and labor? How can we facilitate more open discussions with transparency and deeper sharing among groups who have different priorities, expertise in networks, roles in the movement ecosystem, and kinds of power? Where do we need alignment and shared definitions and where should we hold generative tensions and conflict?

Initially, we considered aligning the group through some shared definitions and research in networks before coming together, but that process seemed time consuming and didn’t fully honor the wisdom in participants’ different perspectives and experiences. Instead of creating written definitions and a compilation of research to align participants on a common framework, we had attendees prepare spark stories – a short story that communicated their experiences and challenges in a network when working across funders, individuals, grassroots organizations, and other entities. Participants shared stories in small groups and each group created an image to show similarities and differences in themes across stories. The storytelling accelerated shared understanding in small groups and highlighted the multiple perspectives in how participants understand and experience networks.

Many participants also shared their spark stories in video conversations. In this video, design team member Allen Kwabena Frimpong and Rachel O’Leary Carmona from AdAstra Consulting share their own definition of a network.

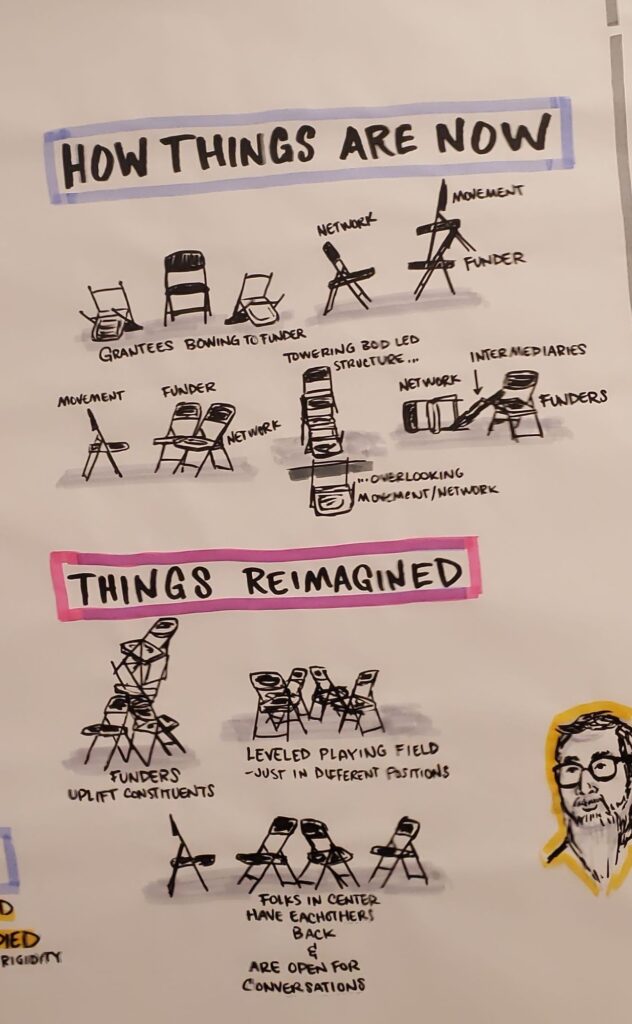

We Used Art Making to Illuminate Power Differences and Start Deeper Conversations about Power Sharing in Networks

Navigating power differentials – including naming and managing them – was a key element in supporting shared learning in this diverse space and also mirrored the ways in which engaging with power can create generative conflict that supports network building or exacerbates unnamed tensions that derail it.

At one point before the convening, some funders were feeling nervous about their power relative to other groups and considered having a separate space. We ultimately decided against that and instead brought funders together to discuss how we might acknowledge and visibilize power differentials (rather than obscure them). We also saw this as a way for funders to build practices for being in spaces where they have more power related to resourcing (such as in a network).

In an exercise from Theater of the Oppressed participants could make visible the power differences between funders that financially resource networks and other network participants. Participants positioned chairs differently based on their vantage point and each new sculpture was in dialogue with the previous one, creating space for different perspectives in support and in tension with each other.

In this spark story, Sage Crump, Cultural Strategist, shares her experience with power as an intermediary navigating the relationships between networked organizations and funders.

Starting with this creative exercise created a bridge to harder conversations about the barriers to equity in resourcing networks such as how money is distributed across network participants, inappropriate use of power, or challenges that come up when there is misalignment between the equity values of a network and the culture of a funding institution.

Convening participants Eugenia Lee of Solidaire and Rajiv Khanna from Thousand Currents discuss what it takes for people inside large funding institutions to align foundation culture with equity and other values needed to better support networks.

We Made Space for New Conversations about Resource Sharing and New Processes for Resource Distribution

Equity should inform how we resource people to be and learn together across power, identity, and roles and then to do together (in networks). Yet external systems, norms, and habits can often inhibit us from living out our values. One example of this is the radical redistribution of resources in neworks, which requires leaning into new practices for how we work together and support each other given our proximity to power and resources.

To financially support people’s attendance at the gathering and their contributions to the space, we created an equity fund. The set-up and distribution of the convening’s equity fund provided the group with an opportunity to lean into these new ways of being. It required vulnerability from participants in asking for what we need and for those holding financial systems to figure out creative ways of reducing the administrative burden on participants, for example by offering stipends rather than reimbursing receipts.

To guide us in these new (to some) ways of being and doing, we created a set of fund principles. Adapted from Leadership Learning Community, the principles included:

- People can ask for what they want and need

- Adopt an abundance mindset (we can always find a way to get more)

- Function with trust, no questions asked

- Give people examples of what they might use funds for (e.g., lodging, childcare, funds to cover a missed day of work for hourly professionals, etc.)

At first, people asked for very little. After more enthusiastic nudges and encouragement to lean into the principles and the discomfort of asking (for example, by looping back to confirm, clarifying our equity principles, and sharing more examples of what people have asked for) more participants felt comfortable asking for what was truly needed.

The initial hesitancy from participants prompted us to think more about who feels entitled to ask for equity funds and how that may relate to our individual sense of worth (eg. how much do I really need this?) and relationship to the collective (e.g., how much might others need relative to me?).

During the convening, we shared what we learned from managing our equity fund in this meme-filled presentation, including how we pushed for a “no receipts” policy, which was challenging to navigate from a compliance perspective but saved a great deal of administrative time.

In this spark story, convening participants Elissa Sloan Perry from Change Elemental and Alexis Flanagan from the Resonance Network share another example of resource distribution within a network, including the vulnerability and trust needed to talk openly about personal wealth as a way towards more equitable resource distribution.

While some of the experiential learnings from the convening are captured above, network practitioners and funders also brought together learnings from past experiences in leading with equity and navigating power differentials within networks including how funders operate in networks; the different forms and shapes networks might take; capacity, impact, and infrastructure needs in networks; and ways of being needed to build, resource, and support networks.

To dig into more stories and insights as well as many other resources about networks, see the report, “Resourcing Networks for Equitable Systems Change: Perspectives from Funders, Intermediaries, Individuals and Organizations on How We Fund and Support Networks for Equity.”

Natalie Bamdad (she/her/hers), joined Change Elemental in 2017. She is a queer and first-gen Arab-Iranian Jew, whose people are from Basra and Tehran. She is a DC-based facilitator and rabble-rouser working to strengthen leadership, organizations, and movement networks working towards racial equity and liberation of people and planet.

Alison Lin (she/her/hers) supports leaders in authentic collaborations to transform people and systems toward love, dignity, and justice. With over 20 years of leadership experience, she draws from work in race equity, complex systems change, organizational development, learning through experimentation and life with a focus on issues affecting LGBTQ and BIPOC communities. She joined Change Elemental in 2017.

Video recording, editing, and photos by Breathe Media Group

Graphic recordings by Brandon Black

Cover photo by Brian Stout

Originally published at Change Elemental

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

The Angel's Mafia: elements to be addressed in peacebuilding governance

Our Better Angels need to get their act together.

I find myself looking back at five years working in peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Almost as long as I spent working as a mechanical engineer in the aerospace field. The business of designing and building spacecraft has one commonality with the “business” of building peace: they both involve people getting together and doing stuff. I used to be weary of the term peace-building as it implies the linear construction of something which can be described as an emergent property of a complex system. What is peace anyway? No, I’m not going down this rabbit hole now, but I leave the open question here for you to entertain yourself with.

You can’t really build peace the same way you build a Falcon 9 rocket. You can’t build the relationships between people the same way you build a clock but you can create the conditions for relationships to emerge, to strengthen and evolve. You can build the scaffolding that makes peace a more likely outcome than violent conflict. A Falcon 9 is just a very complicated clock. Peace is more like a cloud that emerges out of thin, moist air.

Back to my point: I left my engineering career in pursuit of a revelation. And that revelation has come back to haunt me, five years later.

Whether you’re building rockets or building peace, people have to come together and coordinate efforts to accomplish a Mission.

People have to get themselves organized. If it’s the rocket they’re building, the way of organizing is pretty straight forward. It’s a linear process. We’ve been building rockets for quite some time now and have learned a lot about how to do that efficiently. There are still some hiccups every now and then. When these happen, it’s up to the skills and mastery of the project manager (PM) and systems engineers (SE) to make sure they don’t compromise the Mission. The Mission is sacred. You may be an expert planner but as a PM, you’ll be judged by how creative you are when dealing with the hiccups: a delayed supplier, a volcano eruption, a failed test, a new requirement, a pandemic or a world war. The best PM’s I have met in my previous life were those that knew that you need to be ready to deal with contingencies and uncertainty. This is where a good governance system comes in handy. Running the day to day operation of an engineering team requires discipline, practice, expertise and structure. You’re inside a bubble of control. When this bubble bursts and the outside world comes barging in, you need something different. You’re operating in a different regime. The outside world is complex. Full of interconnections and invisible, mysterious forces. Enter the Law of Requisite Complexity which states that “In order to be efficaciously adaptive, the internal complexity of a system must match the external complexity it confronts.” And this was my revelation back in the day: management is different from governance! Management is all about the plan. Governance is about dealing with situations where the plan that you had is no longer the plan that is needed.

With the exception of perhaps the mafia or terrorist neworks, we don’t know how to organize in an enviroment of complexity and uncertainty. Since we enter kindergarten (and perhaps even earlier through models unconsciously passed on by our parents), we are conditioned to think that someone else, a parent, a teacher, a headmaster, a boss, a political leader, a country, a government, an institution, an NGO, you name it, must have The Answer. someone must have The Plan. Someone must have An Understanding of what is going on. Someone will manage it!

When faced with problems that, by definition, have no well defined problem-statement, no boundaries, no solution, we revert to this very rudimentary, almost medieval governance system where a few (typically old, white) men call the shots for all of us. I have nothing against old experienced men calling the shots sometimes (they may have some clever ideas), but I am against this being the only form of social organization in complex environments.

The peacebuilding world has taught me a lot about what it takes to thrive in a complex and ambiguous environment. If you survived a civil war and are engaged in local peacebuilding, you’re pretty much an expert in the Vuca World. I struggled to find my voice in this field. After all, what do I know about peace? I have never heard an AK47 fire.

I found my voice in the overarching theme of social organization and governance. When complexity and uncertainty (aka real life) bursts through your control bubble, that’s when investing in a governance system that obeys the law of requisite complexity makes it or breaks it. After five years witnessing the efforts of 24 South Sudanese Angels coming together for peace, here are a few elements I believe should be addressed when thinking about governance systems.

Communication, language and meetings

Communication is the essence of human social organization. For better and for worse, we’re doomed to use language to communicate and coordinate with one another. The pandemic zoom years have shown us that, while it is possible to keep in touch and even do management decisions remotely, there are times when a face to face meeting is unreplaceable. Whoever feels like a peloton bike is a full replacement of a regular bike has probably never experienced the bliss of a bike ride by the beach in a warm, spring morning.There are moments in the life of a peacebuilder when you literally need to see eye to eye. Feel the energy in the room, let your body speak and listen. There’s simply no virtual replacement for this. The same holds true for any team. There’s simply no replacement for a well facilitated face to face meeting when what’s at stake is the future of the Mission.

Non-violent communication, skillful facilitation of meetings, hosting space for convening, trust building and sharing, are all necessary groundworks for building a solid governance system. The groundwork needs to be in place and ritualized before going into the hard and messy part.

Sense-making, meaning-making, decision-making (SMDm)

What just happened?

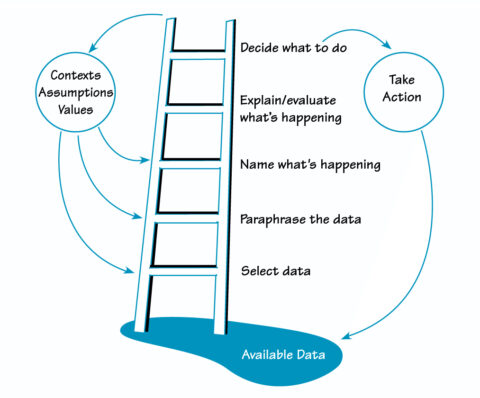

If you’re convening a governance meeting, chances are, something happened. Because everyone on the team is so focused on his or her own subsystem, trying to draw a complete picture may be challenging. Typically, we jump too fast to conclusions here. This is where systems thinking comes into play. Every person in the room will contribute with his / her own perspective on the system and so it’s really important to facilitate a sense-making session that casts a wider, systemic lens on the issue. Whatever happened is the result of a system. Whether you’re aware of it or not, it’s 100% guaranteed that there’s an underlying system moving the pieces. The aim of this sense-making session is to flesh out the elements of this system and move to the next phase of the discussion by asking “What does this mean for the Mission?”

For the engineer working on Falcon 9, it’s relatively straightforward to answer this question. It may take some research, modeling and forecasting but it should be possible to figure out what a delay in the delivery of a component means for the whole mission. Remember, it’s just a very complicated clock, not a cloud.

This is not the case for peacebuilding. The meaning of whatever just happened is deeply related to your own individual meaning making structures and how it is shared with the collective. Collective meaning making in social complex systems is impossible to do without some agreement of what reality is. Without this agreement (or “epistemic commons” if you will) how do we know what we know about the social reality and how do we co-create a shared social imaginary? You need to have a shared dream or shared goal to work towards. Without this shared dreamland, collective meaning making becomes impossible.

If sense and meaning are shared (easier said than done), proposition crafting and refinement should easily flow out of the previous steps. What?, So What?, Now What? This is the way many Western philanthropies and organizations talk about learning and adapting “and governance” itself is a very Western word with all sorts of unintended connotations. However, this is a universal human concept. Every culture has a way of making decisions. We in the Global North tend to sometimes forget that every day all over the world, people in communities come together to come up with proposals to solve problems. Working in smaller teams or networks could prove to be extremely creative and effective if it is coupled with a decision making process, such as consent decision making to fast track good ideas into actionable prototypes and have a basic foundation for what to do when you do not agree or the plan goes sideways.