Understanding network strategy

Every organization needs an effective strategy. Strategy can refer to an overarching strategic plan at the organizational level or a strategy towards achieving specific organizational needs and goals. A strategy will set the way forward for an organization in alignment with its overarching vision and mission. It will articulate the priorities and directions the organization should take as well as convey the “what”, “why”, and “how” to accomplish its goals, often within a given period, by clearly defining the pathways towards achieving them.

At Collective Mind, we’ve learned a number of lessons through our work with networks developing strategies and strategic plans.

Context matters

Strategy for networks is different than strategy for more traditional organizational models. Networks are a unique type of organization with a complex operating model. They are different in how they’re organized, who’s involved, and how they get things done.

First, networks are horizontal, flat structures: they are not top-down, hierarchical, or directive. They are loosely controlled, with multiple mechanisms for collaboration and without any mechanisms for command and control.

Second, networks are comprised of members — without members, you don’t have a network — and the complexity of that membership typically matches the complexity of the network’s issue area. As such, the network must meaningfully integrate a wide diversity of people and/or organizations in an equitable fashion. It must be flexible and agile enough to capture the emergence that arises from such diversity and the interconnections across it.

Finally, because of these characteristics, networks operate differently. They seek to harness the collective intelligence within them, dispersing leadership and sharing decision-making. They typically don’t procure deliverables but focus on stimulating activities by their members, who are responsible for creating the outputs of the network. This relationship between members and the network is typically voluntary and about creating shared value, not premised on a contractual relationship. Consequently, the network’s staff (if there is a staff) aims to support its members by helping facilitate the production of outputs, rather than directly implementing and delivering those themselves.

How networks are different influences strategy

Within this unique and complex operating environment of networks, we can consider strategy differently in at least three ways: process, content, and implementation.

Process: we must ensure that the process to develop the strategy or strategic plan empowers members and any other stakeholders and establishes their ownership of it. This requires a participatory, inclusive process with mixed methods for inclusive, meaningful participation. An iterative and adaptive process should build from one step to the next toward the final strategy. The steps of the process should ensure ongoing triangulation and validation of key ideas, needs, priorities, and pathways with stakeholders as they are developed.

Content: we must ensure that the strategy or strategic plan represents a collective effort. It should set collective priorities and determine the collaborative paths to achieve them by facilitating consensus-building throughout the process. The plan’s priorities and goals should be grounded in the needs, interests, and capacities of the membership. The substance of the plan must reflect the goals, expectations, and motivations of the members.

Implementation: we must clarify and define who will implement the strategy. As explained above, in the context of a network, it must be its members that produce the outputs with support from the network staff. We must clarify how this can be done realistically and right-size the strategy to ensure the feasibility of that implementation (for example, recognizing the limitations on members’ capacity, time, etc.). We must ensure that the plan supports the network to align energy, resources, and stakeholders for collective impact.

A clear and effective strategy will define in what direction the network and its membership will move forward. It will reflect and align with the needs and interests of its members, defining initiatives and activities through which members can participate and collaborate. Consequently, it will clearly articulate the unique added value that the network as a collective can create that is greater than the sum of those parts.

Interested to hear more about how we approach strategy development with networks and how we can support you? Contact Kerstin Tebbe at kerstin@collectivemindglobal.org.

Kerstin Tebbe has almost 20 years of experience supporting networks and multi-stakeholder collaboration. Kerstin founded Collective Mind in late 2019 after many years of independent study and research on networks. With Collective Mind, she has supported networks from local to global on a wide range of challenges. Kerstin has lived and worked in New York, Buenos Aires, Paris, Nairobi, Geneva, and Washington DC. When she’s not thinking about networks, she’s dancing.

originally published at Collective Mind

Illustration by Patrick Hruby, found HERE

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Liberatory Governance... and belonging

How do we organize ourselves... in a world where everyone belongs?

Of the many barriers to living into a world where everyone belongs, this question feels fundamental: how do we organize ourselves? What might it look and feel like to work in an organization without coercion, without domination hierarchies… where everyone belongs?

So today I want to talk about governance. The term sounds bland, but I think it’s sexy: it is the magic that makes everything else possible, and the curse that can undermine even our best work if we don’t pay attention to it. I like this simple definition from the WeGovern community:

Governance is how we choose to be together.

Zen priest and movement strategist Norma Wong names what we all feel, looking out at the world, our institutions, and our movements:

Governance as it exists right now is in collapse.

While I think about governance at every level (family, organization, nation-state), today I want to focus on the scale of an organization, network, or collective: a group of people with a shared purpose and defined membership.

No transformation without governance

I want to thank Brandon Dubé in particular for pushing me, and Building Belonging, to embrace governance as a tool of transformation, and to explore sociocracy in particular. He helped remind us: if governance is about how we choose to be together, then by definition we are all involved in governance all the time, every day, in all of our relationships. Kali Akuno, one of the founders of Cooperation Jackson, agrees:

Governance is just how we make collective decisions together.

In a previous post reflecting on the nature of power, I adopted Priya Parker’s simple definition: “Power is decision-making.” Following this logic, governance is about making visible how power operates, and treating the question of how we wield power with intentionality.

I love Ted Rau’s delightfully provocative question and book: “Who decides… who decides?” If you really sit with it, it’s a radical question, and one that helps distinguish acts of leadership (someone has to speak first, to take responsibility for initiating or facilitating a conversation and the act of collaboration) from acts of domination (preventing others from speaking, my way or the highway, etc.).

Here’s the thing: I’ve come to believe that there is no durable path to transformation without attending to both the process and structure for how we make decisions together in a collective context. As Sean Andrew, Louise Armstrong and Anna Birney explain:

How we relate, work together, and organize are cornerstones of change making… Governance is central to any form of organizing or organization creating change.

We’ve been socialized to view governance as something annoying that gets in the way of “doing the work.” I want to flip this conventional understanding to expose a deeper truth: practicing good governance is the work; without it, anything we create will ultimately be fragile or even antithetical to our aims. As john powell reminds us:

If we don’t do things at a structural level, the structural level will undermine the progress we are making at the personal level.

What we agree on

To generalize broadly we can divide governance into two aspects: structure (think org charts, roles and decision-making authority, etc.) and process (how we make decisions, how we relate to each other). While the two are of course inseparable, today I want to focus primarily on structure: how do we embed the principles of liberatory governance in our org design?

Specifically, I want to distill three foundational principles that practitioners seem to agree on. Of course this is just my subjective perspective; I very much welcome generative pushback and other efforts to synthesize a broad and diverse field.

1. The opposite of coercion is consent

In a world where everyone belongs, we don’t want coercion. As Zakiyya Ismail notes:

Wherever there is coercion, there is oppression.

Dominant culture organizational hierarchies enshrine coercion: “bosses'“ are elevated above other workers; disobey your boss and you risk getting fired. In his beautiful handbook on Mutual Aid principles, Dean Spade notes:

Our society runs on coercion… Most of us have little experience in groups where everyone gets to make decisions together, because our schools, homes, workplaces, congregations, and other groups are mostly run as [domination] hierarchies.

Because we lack practice, too often when we seek refuge from this authoritarian model we make the mistake of swinging to the opposite extremes: either rejecting structure altogether (all hierarchy is bad! inevitably leading to the infamous “tyranny of structurelessness”) or demanding an overly rigid homogeneity that calls for universal consensus. As experiments like Occupy Wall Street have shown, relying only on consensus (everyone agrees on the way forward) is both inefficient and can allow bad-faith actors to impede progress… itself a form of coercion.

The antidote is consent-based governance. As Stas Schmiedt notes:

Consent is how we operationalize liberation.

There are a range of methodologies emerging that seek to codify what a consent-based governance structure/practice might look like; my favorite thus far is sociocracy, a concept given life by the team at Sociocracy for All. This article by Ted Rau is a great introduction, and here is a helpful companion piece distinguishing consensus-based governance from consent-based governance. To be clear: majoritarian democracy (what we purport to practice in the United States) is NOT based on consent. Majority rule doesn’t seek to integrate minority objections; it seeks to overrule them: in my view, that is a coercive system.

The core idea is that the bar for action is not agreement but willingness (a term I prefer to “tolerance”). People can (and must!) object to a proposal that they believe will undermine organizational purpose, but that objection is not a veto: it’s naming an issue that must be addressed and integrated into an improved proposal before it can move forward. The assumption is that the proposal will move forward once the objection has been integrated.

It’s a subtle but radical shift that provides the basis for everything that follows. As the folks at Circle Forward note:

Consent is the foundation for an entire governance system.

2. Structure codifies, reflects, and creates culture

OK, we’re organizing around consent: this is already a radical departure from dominant cultures (and organizational structures) predicated on coercion. But precisely because we have so little practice/training in operationalizing consent, we need help. Our structures have to support us, individually and collectively, in practicing different ways of being. In his comprehensive study about how change happens, sociologist Damon Centola concludes:

We don't make decisions as individuals; we are reciprocally influenced by the environment and people around us… It is largely the structures in which they are embedded that determines whether things work well or not.

On this all the practitioners I follow agree: the structure both reflects and creates culture; it serves to codify how we relate to each other. Tracy Kunkler explains:

Governance is how we set up systems to live our values, and leads to the creation, reinforcement, or reproduction of social norms and institutions. Governance systems give form to the culture’s power relationships.

The folks at Brave New Work name the implication for our org structures:

Whatever we want to be true about the way we relate, is it in the system, is it in the structure?

Taking this question seriously underscores the importance of governance. If we acknowledge that our default patterning is shaped by systems of oppression (white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, etc.), then without intentional effort—and lots of practice!—we are likely to repeat those patterns in our organizations. bell hooks names the challenge:

To build community requires vigilant awareness of the work we must continually do to undermine all the socialization that leads us to behave in ways that perpetuate domination.

Without a structure that supports us in practicing these more liberatory ways of being, we will find ourselves struggling. I love this vulnerable share from Dana Kawaoka-Chen documenting her own efforts at culture-change inside her organization:

Even if I as the executive director had a vision for another way of being, I did not have the organizational structure in place to reinforce a different set of values, which allowed the default operating system to prevail.

3. We want a decentralized structure that enables people to share their fullest gifts

Here we begin to wade into murky waters. I think practitioners generally agree on three things:

- Liberatory governance systems must be decentralized: there is no central command and control structure.

- The structure must seek to, as Alanna Irving notes, “align power with responsibility.” And I would go one step farther: to align responsibility with authority: whoever is best-positioned to act (as a function of the healthy expression of power, whether derived from knowledge, capacity, or relationships) has the responsibility and authority to act.

- The structure must help maximize and channel “discretionary energy” in service of our shared purpose. (Indeed, this has long been one of my core definitions of leadership: the ability to inspire and support others in tapping into the fullest expression of their gifts… and sharing those gifts in support of the collective).

Emergent paradigms seek to solve for these concerns; frameworks like sociocracy do a good job of speaking to the first two points here. While in theory sociocracy can also provide a structure to unlock and channel people’s gifts, I have yet to see it work like that in practice… for reasons I’ll get into below.

Where we still struggle

There is so much that is difficult about this… even as the promise remains tantalizing and delightful when we taste it. As Ericka Stallings notes,

This lack of knowledge about how to operationalize liberatory values exists because we’ve never actually experienced it, so we are almost imagining it into being.

I want to name here three of the core challenges I see that we haven’t yet collectively found a way to effectively navigate. These are areas of experimentation and practice in real time among all the organizations, networks, communities, and collectives that I see on the cutting edge of this work (groups like Wildseed Society, Change Elemental, Resonance Network, the Fierce Vulnerability Network, the Post-Growth Institute, the Thrive Network, and Open Collective, among others).

1. Leadership, agency, power, and self-governance (structure alone will not set us free)

There are books written on each of these topics, but the dynamic I want to highlight here turns on the question of agency (defined as the capacity to exert power).

The general pattern I observe splits along lines of privilege and marginalization. Those socialized into power and privilege, once they become aware of that socialization and not wanting inadvertently to perpetuate domination, shrink from exercising their power: they abdicate their agency (white people in multiracial space, e.g.) At the same time, people marginalized and oppressed by dominant culture have a hard time feeling safe enough to exercise their rightful power. Everyone is afraid to take on the responsibility that comes with leadership, especially amid the radical complexity of proposing a course through uncharted waters… and make decisions that will inevitably have an impact on other people.

The result can be a leadership vacuum, where no one is taking the action that all can see is needed. Gopal Dayaneni names this as one the biggest obstacles we face on the path to liberation:

The primary barrier is our ability to democratically self-govern… The practice of self-governance is the hardest thing. We have to make the hardest decisions, and we don’t have any practice.

Instead, we often look to the structure, or to others with more visible forms of social, positional, or structural power, to get us unstuck. But this misses the point. Quanita Roberson offers this provocation:

So much of what we are struggling with as a culture is that we want everything to be external so that we don't have to take responsibility for what is actually ours to do.

Norma Wong puts it simply: “Transformation requires agency.”

Self-organizing is dead: long live self-organizing!

So here’s the paradox. On the one hand, I agree with Gopal Dayaneni, who declares:

The future must be self-organized.

And I agree with Alanna Irving, who asserts:

I believe there is no such thing as “self-organizing”—there is always work to be done and a skillset required to coordinate people to move together toward a larger shared goal.

The challenge I’m naming here has to do with coming into right relationship with power: our own, others’, and power as made visible and reflected in organizational structure. For self-organizing to work, individuals have to assert agency: to take responsibility for making decisions with and on behalf of the collective. This is by definition an act of leadership. Nwamaka Agbo frames the challenge:

We don’t what it means to lead, until we have to make difficult decisions and take accountability and responsibility for those decisions… collective decision-making still requires that we make decisions.

2. We don’t know what to do with money

If power, agency, and self-governance is hard… that difficulty increases by a degree of magnitude when we introduce money. Two things were clear to me in launching Building Belonging: I wanted to avoid the funder-appeasement / movement-capture trap of the nonprofit industrial complex; and I wanted to avoid the opposite extreme of relying entirely on a volunteer-based community without any money. Both situations risk reinforcing the very power dynamics I want to escape: the gatekeeper model of elite access to funding, or volunteer networks that end up becoming becoming playgrounds for the privileged.

And there’s more: I had a sense that money is one of the most transformative realms of practice available to us; as Orland Bishop reminds us, it is humanity’s largest unconscious agreement.

I love this entire interview with Gopal Dayaneni, where he explains:

The primary reason people pay their rent is because they have no alternative ways to meet their housing needs… It’s not primarily the coercive power of the state or corporations. Rather, we are forced to comply without consent because we have no meaningful alternative.

So even as we focus on developing more liberatory ways of working with money (gotta pay rent!), that’s only half the work: we also have to be devoting energy to meeting our individual and collective needs outside of that system. If we are to transition to a post-capitalist world where everyone belongs, here’s what feels clear to me.

- We have to find ways to meet our needs outside of the money/exchange paradigm (see e.g. this recent post from Mike Strode, exploring some creative ways of flowing value and meeting needs outside the bounded system of money)

- We have to use money to meet our needs in the interim while we remain tethered to that paradigm (see e.g. this discussion of challenges and experiments from Francesca Pick)

- We have to be proactively engaged in both levels at the same time (I love this example from the DisCO cooperative: finding ways to honor the value not only of traditionally remunerative work but also of care work and pro bono contributions)

I’d love to see more examples like DisCO intentionally exploring this space, anchored in indigenous and intersectional feminist principles.

3. Navigating conflict and impact

On this point Kazu Haga is blunt:

The greatest barrier to living and building beloved community is how we navigate conflict.

He may be right: everything else is navigable if we have the skills to transform conflict; not much is possible if we don’t. This has been my consistent lesson from all my work understanding and trying to transform oppressive systems: they depend on separation. Oppressive systems cannot sustain themselves if we have the ability to repair ruptures and reconnect what has been severed. Indeed, I love this definition of leadership from Marcella Bremer, channeling Otto Scharmer:

Leadership is connecting what was separated.

How can we embed accountability and conflict transformation in our structures, when these are fundamentally relational capacities? As Sean, Louise, and Anna remind us:

The nature and quality of our relationships is the foundation of any governance.

I don’t have great answers here. It feels clear to me that a big piece of the work is re-wiring how we understand and relate to conflict: from something bad to be avoided, to Malidoma Somé’s beautiful definition:

Conflict is the spirit of the relationship asking itself to deepen.

My own evolving sense is at minimum every organization/network/collective needs two things:

- The structural equivalent of a help line: where do you go when you find yourself in conflict and unsure how to proceed? I love Alyson Ewald’s idea (from this podcast) of creating a “conflict celebration team.”

- A community-wide commitment to building capacity to navigate conflict, individually, interpersonally, and collectively. This includes trainings and practice, drawing on a growing range of methodologies (I like the framework offered by Deep Democracy, and the skillsets named in Nonviolent Communication, e.g.)

And of course, to name the elephant in the room here: upstream of everything we’re working on is trauma. If we want to come into right relationship with power and agency, hold the tension of navigating money as we transition toward post-capitalism, and transform conflict… we need to find ways individually and collectively to heal from trauma.

Structure is not a panacea. We are still human beings inside of whatever structure we create, with all of our foibles, unhealed trauma, and limited capacity. I’ve written elsewhere about trauma, but need to name it here.

An invitation to practice

If you made it this far, I want to close with an invitation to action, and to feedback: what resonates? What doesn’t? What are you seeing? This work is incredibly difficult… and incredibly liberating, when we find ourselves in structures of belonging.

The WeGovern Community reminds us:

Governance begins with each of us: in practice, in relationship, every day.

I like the way Kim Tallbear expresses our humble aspiration:

We are not trying to get it right, we are trying to get it less wrong, through practice.

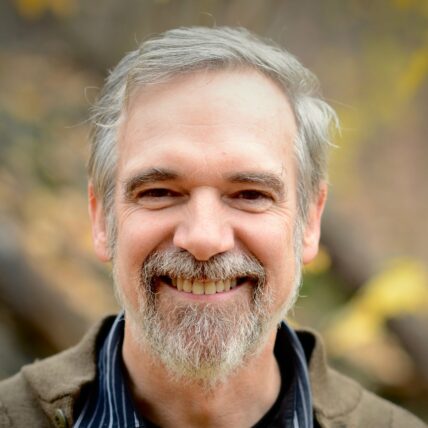

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at building belonging

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

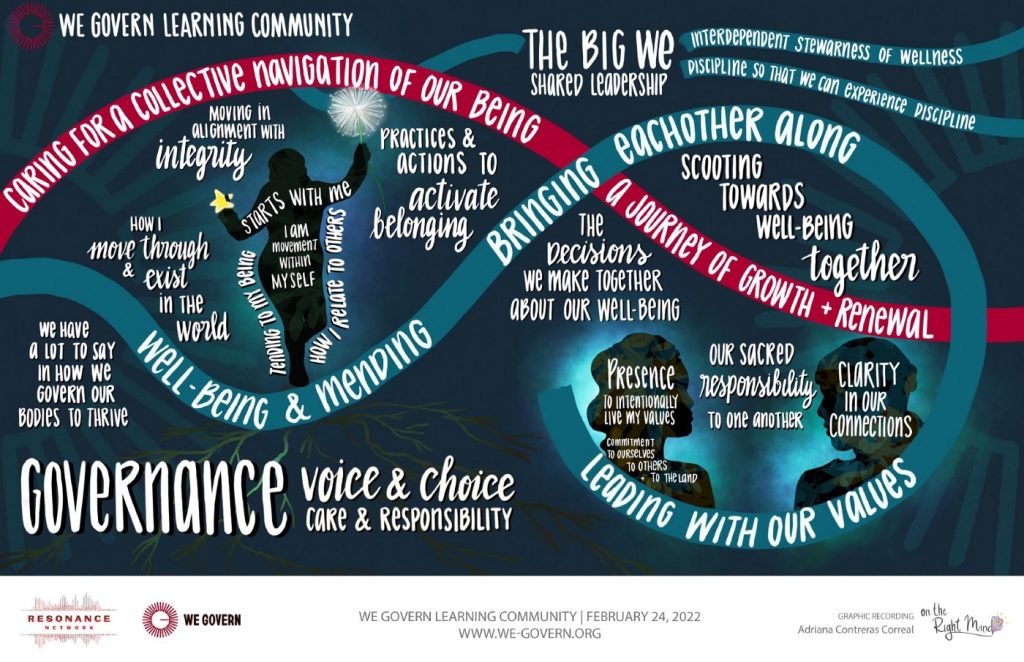

Being in the humanity of governance, with all its messiness and joy

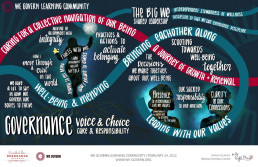

Reflections from the WeGovern Learning Community

How do we build ways of being that uplift the collective dignity, wholeness, and thriving of one another and the lands we inhabit?

How do we build ways of being where our collective wellbeing is carried by community?

How do we create opportunities to live a happy life? To find joy?

WeGovern Learning Community participants are exploring these questions together–discovering what it takes to live into the WeGovern principles today, in our current realities and communities.

This is collective governance, and it takes practice.

* * *

In phase two of the WeGovern Learning Community, a cohort of new and returning participants came together with a shared commitment to collective governance–in practice, embodiment, and reflection. In their first gathering, cohort members delved into what governance means to them, and how it shows up in their lives. Here are some highlights from that conversation:

“I am a movement within myself.” ~ Monique Tú Nguyen

- I used to think there wasn’t a clear rhythm to the way I make choices–that it just sort of happened as things came up. But when I reflected on it, I realized I have a methodical way of making decisions–with myself, choosing who I spend time with and what I spend time doing, and how I care for myself and use my resources emotionally, physically, spiritually, and financially. That’s governance, and there is power in that clarity.

- At work, we have to be clear about documentation; there are clear pathways and decision making protocols–but how are we clarifying, for ourselves, the pathways toward decision making in our own lives, and in our interpersonal relationships?

We are stepping into the sacred responsibility of tending to our own being-ness

- If we are going to be in relationship and connection with others, we have a responsibility to tend to our own being–our own healing, our own growth. Everything else comes from that place–our practices, our placemaking, how we cultivate belonging, and how we become aware of our needs–and make choices to make sure those needs are met.

- It is the values and choices that I practice every day, in all the unfolding moments. I am choosing wholeness and listening and vulnerability

“When I think about the ways I engage with governance the most, it’s in the relationships I touch every day–my relationship with myself, my relationship with my dog, my relationship with my partner, and in my caregiving relationship with my mom, who has dementia.”

-Alexis Flanagan

There is power in visibilizing our governance practice(s)

- And it’s important to name governance as governance — to visibilize our practice, so we can bring people along

- We are cultivating a sense of responsibility for the way we move through the world. From the moment we get out of bed in the morning, how are we living our values? It’s so easy to let that process be invisible, but so important to bring it to light.

Governance is the gas pedal on the tractor

- If I imagine my life as driving a tractor, what’s accelerating me forward is my own choices. I want to move forward in alignment and with integrity, so that my thoughts and feelings and actions are all in harmony with each other. And I feel right with myself.

- Meanwhile, it’s important to make sure that I am being transparent about my choices in the world–because it’s not enough for me personally to just do the thing. If I don’t voice the value I’m living into, people may see what I’m doing but not understand why. We have a responsibility to bring people along.

“We are scootin’ toward the interdependent stewardship of wellness” -Aaron Spriggs

- Governance is about the big ‘we’. When we understand we as ‘all of us together,’ we consider the moves we make–and the way we impact each other–differently

- Governance is stewardship; it’s caring for the collective navigation of our beingness.

- Our decision making together brings in every part of us, and all of the ecosystems around us into how we’re making every single choice, how we’re moving through our days.

“I am honoring and orienting towards wellness and nourishment–and I practice that in how I speak internally to myself, how I choose to speak in a shared place, how I choose to navigate things like making food in my kitchen–all the choices I make that are interconnected with other people, that impact me and the people around me are all part of that building out into the world we want to live in.”

-Reese Hart

Collective governance is a discipline we choose, so that all people may experience dignity

- We are building strategies to prevent future harm while also taking time to imagine what governance looks like outside of the current structure we live in, that continues to cause harm

- To govern, you need to think about what breaks your heart. And also what you love–and that’s going to help you be who you are in the world. — Rose Elizondo

Governance is a lifelong journey

- Just as in nature’s rhythm of seasons, we are renewing ourselves constantly–our needs are not the same, moment to moment; our bodies are not asking for the same things

- Being able to be open and responsive in the natural ebbs and flows is part of governance practice–it is an ongoing journey of renewal and growth

Governance is the restoration of birthright

- All of us are part of a lineage–we are coming back into ourselves and our humanity, choosing and creating the life we want to live, with the people and beings we want to be with. Almost like we are revisiting our childhoods and getting to raise ourselves–we are deciding who we are, who we want to be, and how we want to relate to (and with) others. How we want to be seen.

- And the capacity for this is something we’re all born with–we don’t have to achieve or acquire; our capacity for governance is already within us. And the more we can see that, the less alone we feel.

“This enormous world I’m part of is always going to be big enough for whatever I evolve into.” -Yesenia Veamatahau

The stance, self care, investment, and spaciousness to be present to what’s happening around us. To step into the choices, in each moment, that enable us to live our values, we need to be present to connections, community, and portals–like the land. Land connects us to today, tomorrow, yesterday. We need to breathe into compassion, boundaries, and love.

We are learning to really be with ourselves–and witnessing the ripple effect that has on others.

Collective governance is rooted in Indigenous peacemaking and restorative justice practices, incorporating laws of nature and spirit.

Forrest Landry says that love is that which enables choice. And perhaps the same is true for governance that Dr. Cornel West says about justice–that it’s what love looks like in public. Governance is ultimately a collective practice–one we are delving into in times of deep uncertainty, isolation, and struggle. We are building when we need to most, the kind of governance we know is possible. Beginning with the choices we make today.

* * *

The reflections in this post were shared during the first gathering of the WeGovern Learning Community Phase 2. Just as the governance we practice, this discussion was a collective endeavor. Deep gratitude to all participants for their presence and contributions: Benjamin Carr, Reese Hart, Monique Tu Ngúyen, Crystal Harris, Ed Heisler, Sarah Curtiss, Leta Harris Neustaedter, Aaron Spriggs, Judith LeBlanc, Lonnie Provost, Brittany Eltringham, Heidi Notario, David Hsu, Adriana Contreras, Estefania Mondragon, Jenni Rangel, Ruby Mendez-Mota, Jovida Ross, Shizue Roche Adachi, Alexis Flanagan, Aparna Shah, Doris Dupuy, Kassamira Carter-Howard, Megan Shimbiro, Yesenia Veamatahau, Karen Tronsgard-Scott, Anne Smith, and LaToria White.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Inside philanthropy and networks

Collective Mind hosts regular Community Conversations with our global learning community. These sessions create space for network professionals to connect, share experiences, and cultivate solutions to common problems experienced by networks.

In July 2021, Collective Mind hosted a unique Community Conversation panel discussion about philanthropy and networks. The session featured experts who work across the philanthropic space and have deep experience with networks ranging from global and national to hyper-local levels and across the gambit of social causes. The panel included Heather Hamilton, Executive Director of the Elevate Children Funders Group; Hilesh Patel, Leadership Investment Program Officer of the Field Foundation; and Katie Davies, Manager of Strategic Networks Initiatives with Ignite Philanthropy.

Together, the panelists explored the most urgent topics on their minds as funders and funder organizers for social impact, and talked about the trends they’re observing within philanthropy as it evolves toward more progressive causes and systems-change work. The panel helped elucidate some of the mysteries behind philanthropic decision-making and strategy, and sparked conversation among participants about how networks can reimagine their approach to and relationships with donors.

Highlights from the conversation

Understanding the decision-making structures of philanthropies helps network practitioners see their work through a donor’s lens and ask themselves the questions donors need to have answered. According to the panel, grant seekers commonly overlook the disconnect between program officers (POs) and where high-level funding decisions are made. POs are engaged on the ground, hearing directly from leaders and impacted communities, and have a current view of how the field is evolving to help advise on strategy. But ultimately, the Board of Directors controls the purse strings and sets the strategic agenda, with POsimplementing their decisions. Boards often prioritize questions of financial risk when making strategy and investment decisions, as well as the potential for fiscal return or reward. Among the range of types of foundations, POs will also have different levels of autonomy and instruction and at times won’t have a lot of flexibility in what they can fund. For networks, this can be particularly challenging as the work and value of networks can be amorphous and long-term, presenting more perceived risk from a business point of view.

Furthermore, networks may not necessarily fall into the framework of how traditional Boards think of how change happens. By design, networks work collectively toward a goal or contribute to a solution, rather than being able to specifically claim impact as their own, which makes their value proposition less straightforward and tangible than programmatic outputs and numbers. To demonstrate impact for donors and stakeholders, groups will sometimes overclaim and attribute wins to their own efforts, which misrepresents the work and can undermine the notion of a shared purpose. This can muddle the message of how collective impact happens and its value. It is therefore both on networks to be thoughtful, effective storytellers and have strong mission clarity, and on donors to educate and challenge themselves on their conceptions of the role and value of networks to affect systems change and foster an enabling environment where change happens.

Effective philanthropy requires more and better Board education. At its roots, philanthropy assumes a binary between those doing work on the ground and seeking funds and support, and those with resources who make big decisions on behalf of social change work but have limited practical knowledge or experience of it. This dynamic is challenging to navigate and also problematic. More and more, POs are working to educate Boards, which are often composed of wealthy individuals, about social change and to create change within foundations on the inside. There is emerging interest in the philanthropic space to learn from and with communities of change and to become more responsive and accountable across leadership and decision-making. Networks can help POs in their efforts to push and educate leaders within foundations to understand more about movements, collectives, and networks, and how donors can be more effective partners for change.

One way this can be done is through measurement methods that are more true to life and the work of social change. Donors often miss that funding networks means that progress won’t always be linear or explicit. Not only can fixed metrics and reporting requirements put a burden on grantees and have undue influence on the work, but limiting impact work to spreadsheets and formulaic processes can drive artificial outcomes and stifle the chance to glean real learning and value. For some foundations, there’s a new effort to pivot traditional reporting requirements and formats to be more flexible, conversational, and focused on multi-directional learning. These processes reframe accountability to center what grantees and donors can learn from each other about how the field is evolving, what role they all play, and what progress is being made. Doing the work to understand why networks and coalitions are important leads to understanding the nature of networks and systems change.

Donors are also starting to embrace how the image and dynamics of leadership are shifting through the work of networks and movements. Whereas traditional leadership is marked by an individual with certain, often normative characteristics and the vision and actions they represent, networks and movements center the leadership of groups and shared efforts. In networks, there is often no one leader: leaders are pulled from different sections to be part of broader work, and the model and mission doesn’t prioritize individuals as leaders. These challenges to traditional notions of what leadership looks like both mirrors and goes beyond how the face of leadership is already changing generationally. Understanding networks for how they upend traditional leadership is another way to educate philanthropic Boards about collective action and collaborative leadership.

Miss the session? View the recording here.

Thanks again to our amazing panelists!

Emily is a seasoned nonprofit and social impact expert with 14 years of experience leading social justice organizations and programs from community to global levels. She specializes in program innovation and design, strategy and leadership, facilitation, and peer learning. Among Emily’s career highlights, she has served as Executive Director of a grassroots women’s rights and anti-violence organization in British Columbia, Canada; spearheaded global peer exchange networks and innovative women’s leadership programming; and designed cutting-edge participatory research about GBV in remote and Native communities.

Originally published at Collective Mind

Featured image found here

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

The Angel's Mafia: elements to be addressed in peacebuilding governance

Our Better Angels need to get their act together.

I find myself looking back at five years working in peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Almost as long as I spent working as a mechanical engineer in the aerospace field. The business of designing and building spacecraft has one commonality with the “business” of building peace: they both involve people getting together and doing stuff. I used to be weary of the term peace-building as it implies the linear construction of something which can be described as an emergent property of a complex system. What is peace anyway? No, I’m not going down this rabbit hole now, but I leave the open question here for you to entertain yourself with.

You can’t really build peace the same way you build a Falcon 9 rocket. You can’t build the relationships between people the same way you build a clock but you can create the conditions for relationships to emerge, to strengthen and evolve. You can build the scaffolding that makes peace a more likely outcome than violent conflict. A Falcon 9 is just a very complicated clock. Peace is more like a cloud that emerges out of thin, moist air.

Back to my point: I left my engineering career in pursuit of a revelation. And that revelation has come back to haunt me, five years later.

Whether you’re building rockets or building peace, people have to come together and coordinate efforts to accomplish a Mission.

People have to get themselves organized. If it’s the rocket they’re building, the way of organizing is pretty straight forward. It’s a linear process. We’ve been building rockets for quite some time now and have learned a lot about how to do that efficiently. There are still some hiccups every now and then. When these happen, it’s up to the skills and mastery of the project manager (PM) and systems engineers (SE) to make sure they don’t compromise the Mission. The Mission is sacred. You may be an expert planner but as a PM, you’ll be judged by how creative you are when dealing with the hiccups: a delayed supplier, a volcano eruption, a failed test, a new requirement, a pandemic or a world war. The best PM’s I have met in my previous life were those that knew that you need to be ready to deal with contingencies and uncertainty. This is where a good governance system comes in handy. Running the day to day operation of an engineering team requires discipline, practice, expertise and structure. You’re inside a bubble of control. When this bubble bursts and the outside world comes barging in, you need something different. You’re operating in a different regime. The outside world is complex. Full of interconnections and invisible, mysterious forces. Enter the Law of Requisite Complexity which states that “In order to be efficaciously adaptive, the internal complexity of a system must match the external complexity it confronts.” And this was my revelation back in the day: management is different from governance! Management is all about the plan. Governance is about dealing with situations where the plan that you had is no longer the plan that is needed.

With the exception of perhaps the mafia or terrorist neworks, we don’t know how to organize in an enviroment of complexity and uncertainty. Since we enter kindergarten (and perhaps even earlier through models unconsciously passed on by our parents), we are conditioned to think that someone else, a parent, a teacher, a headmaster, a boss, a political leader, a country, a government, an institution, an NGO, you name it, must have The Answer. someone must have The Plan. Someone must have An Understanding of what is going on. Someone will manage it!

When faced with problems that, by definition, have no well defined problem-statement, no boundaries, no solution, we revert to this very rudimentary, almost medieval governance system where a few (typically old, white) men call the shots for all of us. I have nothing against old experienced men calling the shots sometimes (they may have some clever ideas), but I am against this being the only form of social organization in complex environments.

The peacebuilding world has taught me a lot about what it takes to thrive in a complex and ambiguous environment. If you survived a civil war and are engaged in local peacebuilding, you’re pretty much an expert in the Vuca World. I struggled to find my voice in this field. After all, what do I know about peace? I have never heard an AK47 fire.

I found my voice in the overarching theme of social organization and governance. When complexity and uncertainty (aka real life) bursts through your control bubble, that’s when investing in a governance system that obeys the law of requisite complexity makes it or breaks it. After five years witnessing the efforts of 24 South Sudanese Angels coming together for peace, here are a few elements I believe should be addressed when thinking about governance systems.

Communication, language and meetings

Communication is the essence of human social organization. For better and for worse, we’re doomed to use language to communicate and coordinate with one another. The pandemic zoom years have shown us that, while it is possible to keep in touch and even do management decisions remotely, there are times when a face to face meeting is unreplaceable. Whoever feels like a peloton bike is a full replacement of a regular bike has probably never experienced the bliss of a bike ride by the beach in a warm, spring morning.There are moments in the life of a peacebuilder when you literally need to see eye to eye. Feel the energy in the room, let your body speak and listen. There’s simply no virtual replacement for this. The same holds true for any team. There’s simply no replacement for a well facilitated face to face meeting when what’s at stake is the future of the Mission.

Non-violent communication, skillful facilitation of meetings, hosting space for convening, trust building and sharing, are all necessary groundworks for building a solid governance system. The groundwork needs to be in place and ritualized before going into the hard and messy part.

Sense-making, meaning-making, decision-making (SMDm)

What just happened?

If you’re convening a governance meeting, chances are, something happened. Because everyone on the team is so focused on his or her own subsystem, trying to draw a complete picture may be challenging. Typically, we jump too fast to conclusions here. This is where systems thinking comes into play. Every person in the room will contribute with his / her own perspective on the system and so it’s really important to facilitate a sense-making session that casts a wider, systemic lens on the issue. Whatever happened is the result of a system. Whether you’re aware of it or not, it’s 100% guaranteed that there’s an underlying system moving the pieces. The aim of this sense-making session is to flesh out the elements of this system and move to the next phase of the discussion by asking “What does this mean for the Mission?”

For the engineer working on Falcon 9, it’s relatively straightforward to answer this question. It may take some research, modeling and forecasting but it should be possible to figure out what a delay in the delivery of a component means for the whole mission. Remember, it’s just a very complicated clock, not a cloud.

This is not the case for peacebuilding. The meaning of whatever just happened is deeply related to your own individual meaning making structures and how it is shared with the collective. Collective meaning making in social complex systems is impossible to do without some agreement of what reality is. Without this agreement (or “epistemic commons” if you will) how do we know what we know about the social reality and how do we co-create a shared social imaginary? You need to have a shared dream or shared goal to work towards. Without this shared dreamland, collective meaning making becomes impossible.

If sense and meaning are shared (easier said than done), proposition crafting and refinement should easily flow out of the previous steps. What?, So What?, Now What? This is the way many Western philanthropies and organizations talk about learning and adapting “and governance” itself is a very Western word with all sorts of unintended connotations. However, this is a universal human concept. Every culture has a way of making decisions. We in the Global North tend to sometimes forget that every day all over the world, people in communities come together to come up with proposals to solve problems. Working in smaller teams or networks could prove to be extremely creative and effective if it is coupled with a decision making process, such as consent decision making to fast track good ideas into actionable prototypes and have a basic foundation for what to do when you do not agree or the plan goes sideways.

Finally, the governance process should answer two cornerstone questions: accountability and legitimacy. Whatever comes out of the process must be accompanied by a clear statement of accountability (who has skin in the game?) and legitimacy. In Western contexts, charters, MoU, constitutions, manuals, contracts, can play a role here. But these can overcomplicate the real work. What I have found in my time in peacebuilding is that the deepening of relationships and agreement for action can start with three questions. What do we want to do together? How will we make decisions? What do we do when we don’t agree? In short, how do we want to show up together? This is one area where I think there’s a lot to innovate in civil society movements. Peacebuilders can learn from movement activists how to set the foundation for adapting quickly while keeping a focus on the desired goal.

Organizing for Peace

Kurt Vonnegut knew it: “There is no reason why good cannot triumph as often as evil. The triumph of anything is a matter of organization. If there are such things as angels, I hope that they are organized along the lines of the Mafia.”

I believe that our perennial mission is to organize. We do that so elegantly with clock problems. Now it’s time to complement that toolset with other rituals that help us organize around cloud problems, too. I hope Pinker’s Better Angels take a lesson or two from the Mafia, but outrage or hope alone won’t cut it. I believe there’s a lot to be done to help peacebuilders around the world get organized in a way which creates, not a rigid, but an emergent order that is able to sense and respond to the challenges posed by the destructive forces of violence and war.

Pedro Portela is the Founder of the Hivemind Institute, a think tank and action research organization in Portugal dedicated exclusively to prototype new models of local organization, advocating for more systems literacy and proposing networked approaches to complex social problems.

Originally published at The HiveMind

featured image found HERE

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

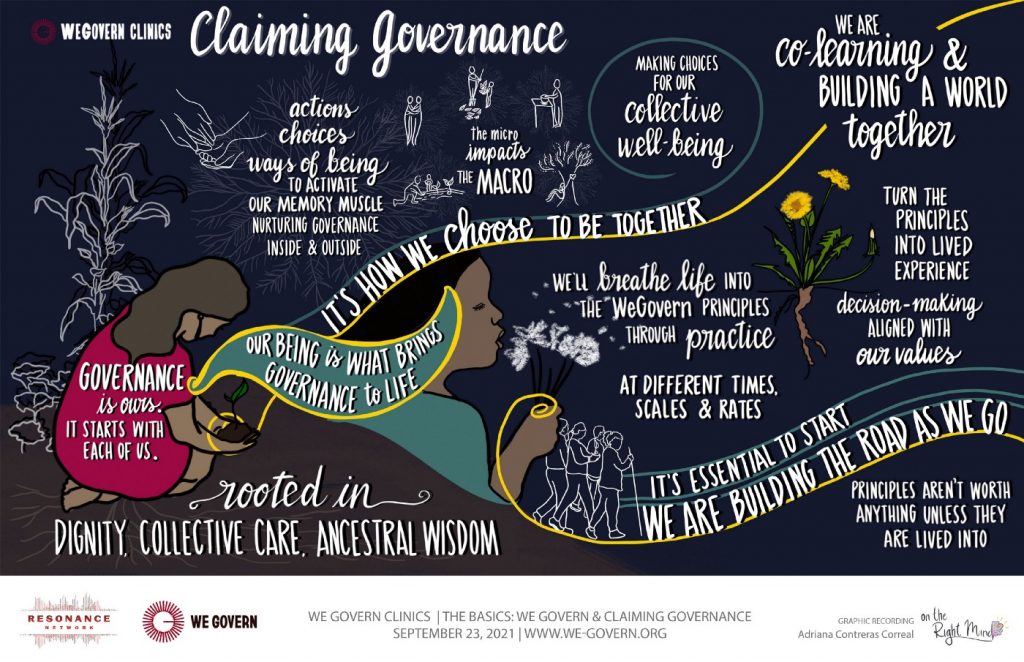

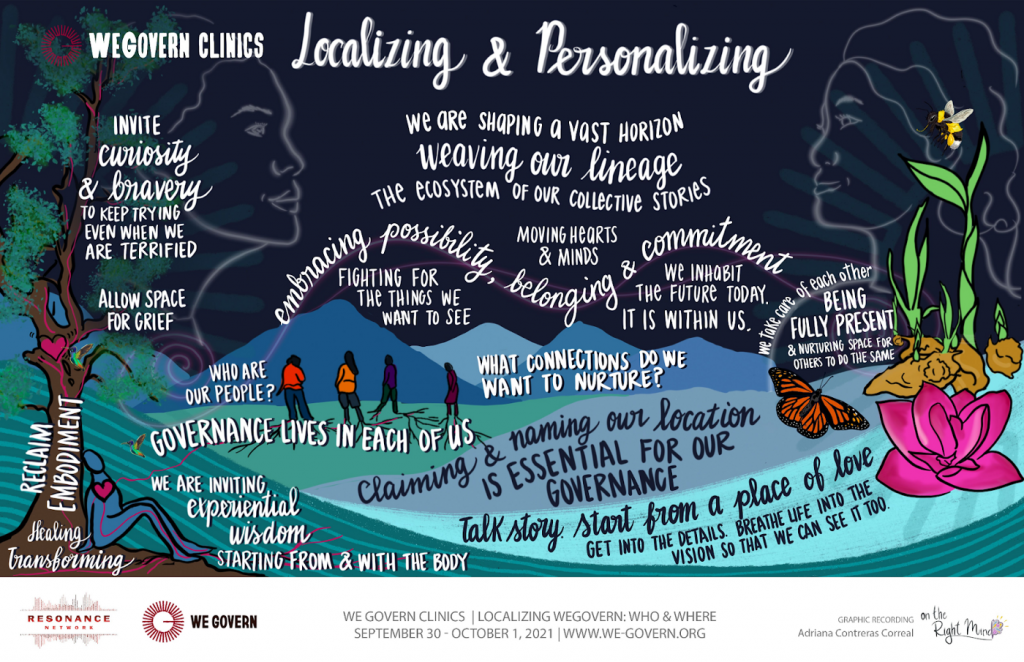

Governance is how we choose to be together

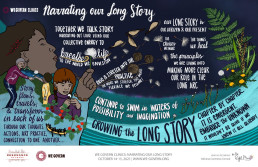

An illustrated story of liberatory governance practice

Storytelling — like governance — can take many forms.

When choosing new ways of being together, we begin with ourselves — in our bodies, hearts, spirits. The choice to be in governance rooted in mutual care is an embodied one. Once it rests within us, the practice begins.

Accordingly, the story of governance practice is a multi-sensory one. It takes shape in the colors, textures, voices, sounds, and sensations of our beloved communities — it is multi-dimensional.

Last year, a group of worldbuilders came together with a shared commitment to collective liberation — and the governance principles we’ll need to bring it into being. Together, we moved through a series of clinics to deepen our collective governance practice.

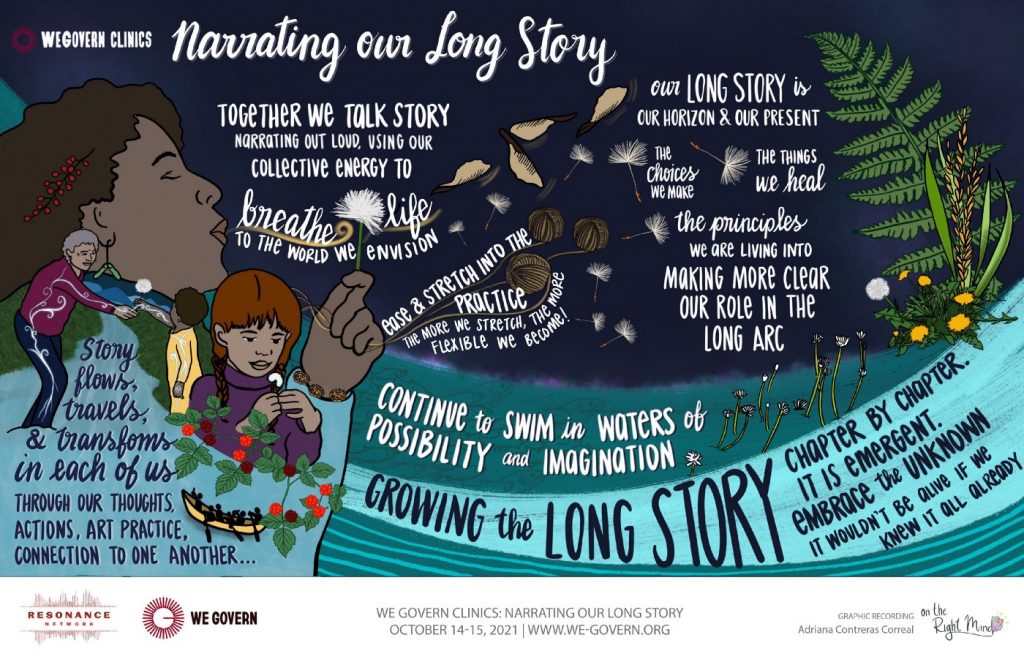

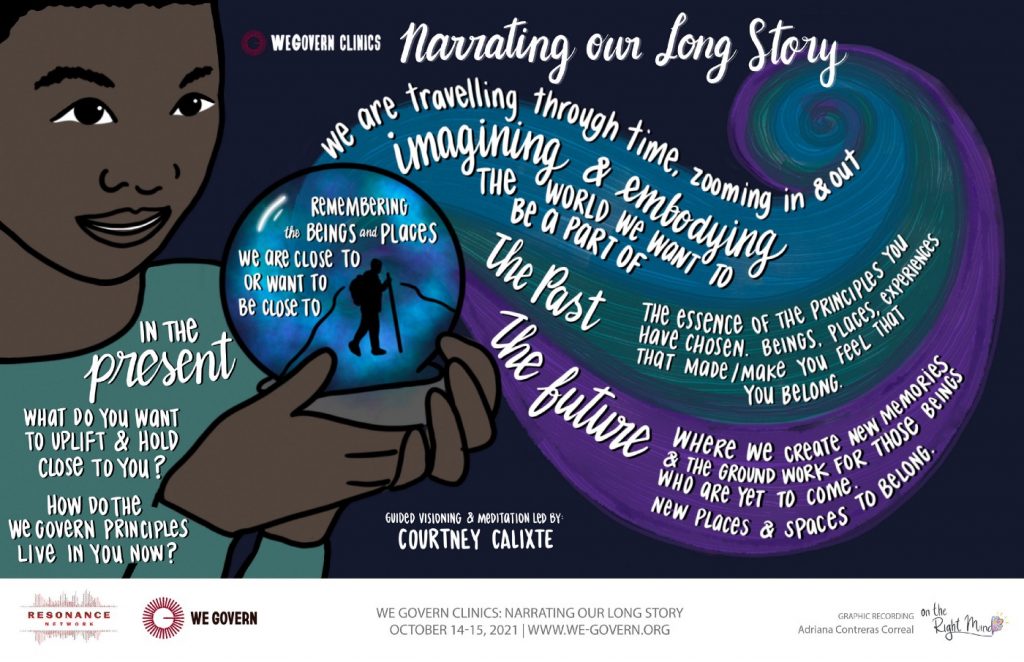

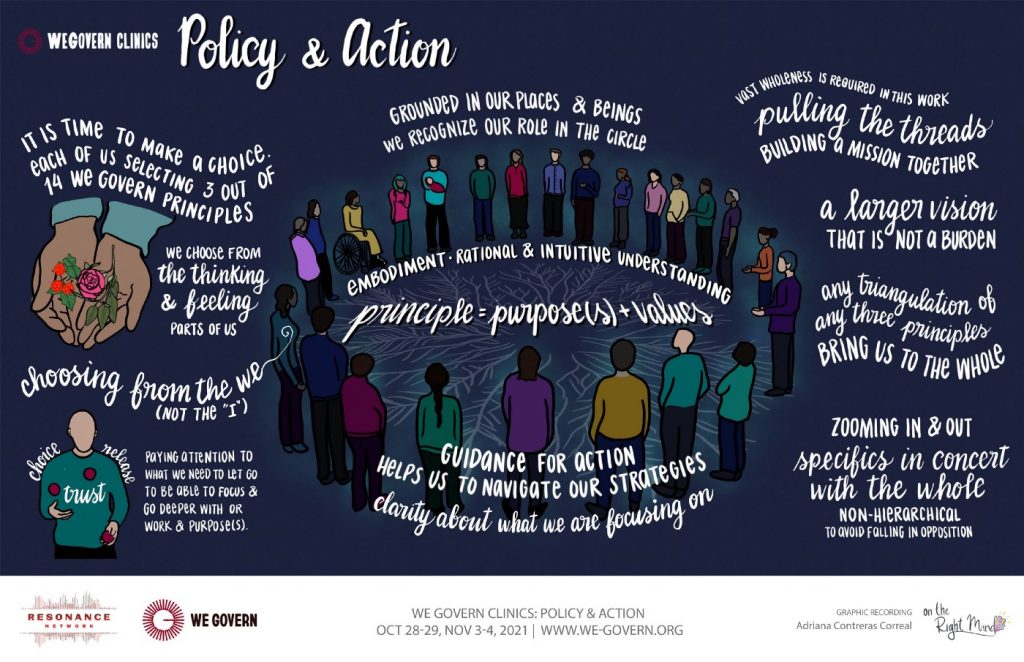

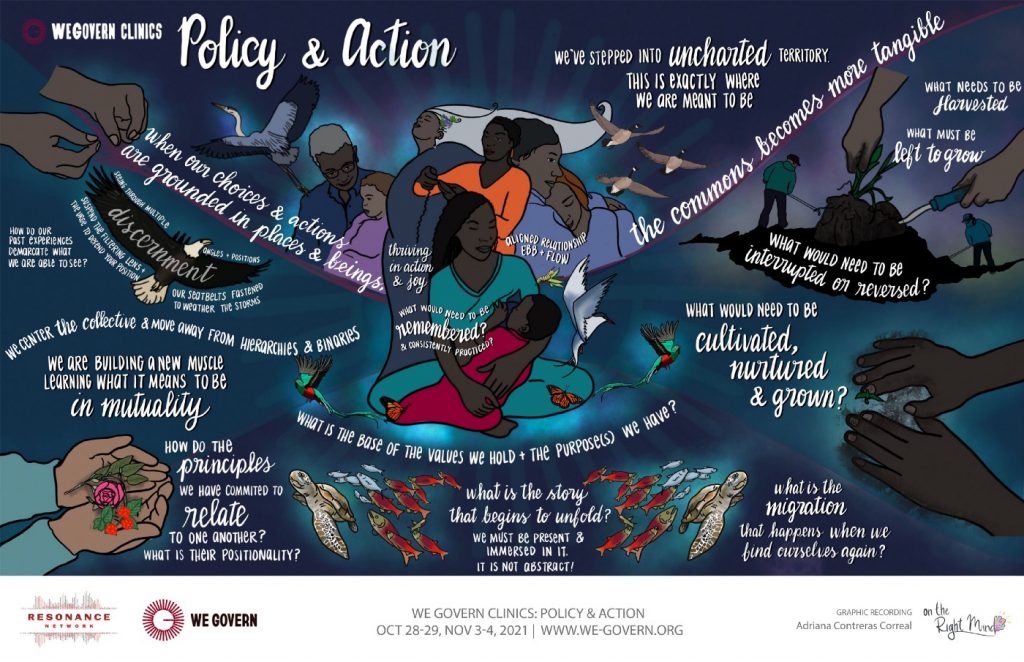

What follows is a constellation of words, images, and musical offerings to describe this journey into liberatory governance. These images are the work of our beloved Adriana Contreras Correal of On the Right Mind. Deep gratitude to Adriana for sharing her gifts with us.

We invite you to enjoy our practice playlist and delve into the story below…

Collective governance begins with a choice: to commit to the ways of being that enable all beings to thrive:

Transformation begins when it’s personal: once we’ve committed to collective governance, we begin by grounding in place. Our work begins at home:

As our practice takes root, we continue illuminating the path toward what is possible, by narrating our visions for our communities into story:

Holding close to our stories of liberatory futures, we focus in on policies and actions we will need to sustain a world beyond violence — a world where all beings can thrive:

Originally published at Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Experimenting Towards Liberated Governance

Over a year ago, Vu Le published an article about the current models for nonprofit boards. The title “The default nonprofit board model is archaic and toxic; let’s try some new models” doesn’t bury the lede. Of the current models, Le writes:

“Over the years, we have developed a learned helplessness, thinking that this model is the only one we have. So we put up with it, grumbling to our colleagues and working to mitigate our challenges, for instance figuring out ways to bring good board members on to neutralize bad ones or having more trainings or meetings to increase ‘board engagement.’”

At Change Elemental, we have been experimenting with some new governance models, informed by the work of our clients, partners, and many others in the field who are trying out new structures and ways of governing. For example, Vanessa LeBourdais at DreamRider Productions has shared principles and practices of “evolutionary governance”, and Tracy Kunkler at Circle Forward has supported our learning about consent-based decision making. Countless other groups who have continued to uphold and practice historic, ancestral, Indigenous, and intergenerational structures of governance—and have informed these other values-aligned governance models—have catalyzed our learning.

Here, we offer a specific window on the evolution of our board, including some practices we’ve dreamed up, borrowed, and re-remembered to align governance with our values in a nonprofit system set up to default to white supremacy, paternalism, power over, and other oppressive habits.

The following questions have formed the basis of our governance and leadership evolution (we’ve shared more about our leadership evolution in recent blog posts here and here):

- How might we realize deep equity and liberation in leadership and governance?

- How might we evolve leadership and governance structures to share power and work in more networked ways?

- How might we align leadership and governance practices and culture with our values?

Our journey began a few years ago when our board and core staff team began to get curious about what it might look like to think about our board as mycelium. Mycelium are fungal networks that spread across great distances within soil (and sometimes underwater) and process nutrients from the environment to catalyze plant growth, supporting ecosystems to thrive. In our context, we use mycelium to refer to the powerful network of tendrils and roots that connect our board and core team to other people, groups, and organizations, enabling us to turn toxins into nutrients and nourish ourselves through our relationships to ensure collective thriving and care.

Here is what we’ve learned so far in our governance evolution (from the core team perspective—more from our governance team coming soon!):

Shifting language from “board” to “governance team” helped us reframe the governance team’s role.

Early on we shifted from referring to our board as “a board of directors” to a “governance team.” Tracy Kunkler of Circle Forward offered this definition in a small group experiment on governance we facilitated:

“Every culture (in a family, a business, etc.) produces governance — the processes of interaction and decision-making and the systems by which decisions are implemented. Governance is how we set up systems to live our values, and leads to the creation, reinforcement, or reproduction of social norms and institutions. Governance systems give form to the culture’s power relationships. It becomes the rules for who makes the rules and how.”

Shifting language supported us to shift our mindsets about governance. This language guided us towards greater clarity about our own governance team’s role: co-creating systems and practices that can support and catalyze us to live our values. It also deeply shifted how we both hold and reimagine the boundaries between the 12 people on our governance team, our core team (staff), and other partners to be more porous and center collaboration, emergence, and our interconnectedness.

However, because shifting mindsets requires shifting patterns and practice, this switch in language isn’t simple. We have noticed that we sometimes revert to using the term “board” rather than “governance team” when we are talking about potential barriers that the board may present or “traditional” board responsibilities such as fiduciary oversight. This is a work in progress and when we find ourselves reverting to old language, it is a signal that we might be in older practices, patterns, or ways of thinking about our relationship to the governance team and its role that are no longer serving us or our work.

Practicing liberatory governance is having one foot on land and one in the sea.

Getting clearer on our governance team’s role deepened our sense of what it might look like to realize deep equity and liberation in governance. We began to understand what “liberatory governance” could look like for us—a governance team that partners with us to bridge between current reality and the future we’re building by: moving the organization towards greater alignment with our values; and co-creating liberatory systems and ways of working together that can transform the larger oppressive systems we’re operating within. We talk about this internally as “having one foot on land and one on water,” a metaphor Hub member Elissa Sloan Perry shared from Alexis Pauline Gumbs. Gumbs hears best with “one foot in the water, one foot in the sand.”

In our organizational context, the “water foot” attends to things like our vision, uninhibited aspirations, values alignment, and acting today in ways that prefigure the world we want to see. The “foot on land” takes into account the world as it is, such as the requirements and legal constraints of our 501.c.3 tax designation, and current financial realities and access to other resources, where trust-based relationships can sometimes become transactional or even litigious. Our governance model values both “feet” in its awareness and decision-making. When we make decisions, the “water foot” leads with the “land foot” as a valued, supporting, and crucial partner.

Creating multiple, fluid points of connection across the staff and governance team helps build the relationships and trust necessary for shared leadership and power.

Building trust and mutual accountability are at the heart of our evolving governance structures and practices, just as we have found it to be in building toward shared power and leadership at the staff level. This work is more time-consuming than conventional governance models so we needed to build our collective capacity for sensing what is actually too much time. We also needed to strengthen our skill and capacity for generative conflict including discerning when to: enter into conflict and tension; sit with it so that we can reflect and discuss later; and/or intentionally let it go. This has meant getting more comfortable with sitting in discomfort when conflict can’t (or shouldn’t) be resolved immediately.

Some simple structures and systems support us in developing these capacities and discerning what is needed to build trust and move through conflict. For example, we wanted more interaction between our core team (staff) and the governance team, but didn’t want to necessarily add more large group meetings—we wanted connections to be deep and purposeful. To create purposeful connections, where a broad range of staff and governance team members could develop relationships and bring their unique gifts, we opted to have governance team co-chairs work with a staff liaison. The staff liaison partners with different staff, bringing different people into conversations with the co-chairs and other governance team members where their experience, wisdom, and gifts are critical. The co-chairs and other governance team members then connect together and separately into different areas of work based on their interests, skills, and what is needed.

We also evolved our governance team meeting structure to have staff members join for key sections of the meeting. We share the agenda in advance and offer some guidance to help staff decide when they might join or when they might opt out of a meeting. Additionally, staff and governance team members now caucus separately at the end of each governance team meeting to debrief and raise unresolved issues with the intention of sharing back what needs the full group’s attention. The caucuses support greater truth-telling across the governance team and core team, deepen our understanding of each other’s perspectives and help us dig into conflict with love and rigor.

Grounding in shared values is critical for practicing liberatory governance.

If you were to review the specifics of our governance team’s role, you might not find anything surprising or “new.” The difference is in how the governance team carries out these responsibilities – with a rooting in shared values with staff and commitment to working through differences in values when they show up.

In recruiting and engaging governance team members, we haven’t just sought out individuals who conceptually agree with our values (which were reflected in our recruitment criteria), but people who are game to experiment on what it looks like to make decisions rooted in those values. People who already embrace and practice inner work, multiple ways of knowing, experimentation, and emergent strategy—and who are looking to upend traditional governance team models and create and remember anew.

Even with the perfect container, structure, and systems, it’s the people who make up our core team (our staff) and governance team – their own values as well as their willingness to be in the generative tension that helps support shared values – who have accelerated our work in shared power and leadership both on the core and governance teams. Together, we are living into our vision and deepening our practices of shared leadership and shared power to shift conditions towards love, dignity, and justice.

Look out for more learning from these experiments in liberatory governance in the new year!

Natalie Bamdad (she/her/hers), joined Change Elemental in 2017. She is a queer and first-gen Arab-Iranian Jew, whose people are from Basra and Tehran. She is a DC-based facilitator and rabble-rouser working to strengthen leadership, organizations, and movement networks working towards racial equity and liberation of people and planet.

Mark Leach (he/him/his) has over thirty years of experience as a researcher and management consultant. Mark has a particular interest in strategy, leadership development and transition, and issues of equity and inclusion in organizations.

Originally published at Change Elemental

Banner Photo Credit: Kirill Ignatyev | Flickr

Governance – the overlooked route to transformation: How can we best organise for change?

What are the current governance approaches and ways of organising that are being used in attempts to create systems change? What would more systemic governance approaches for our work look/feel like and how might we transition to these?

Part one in a series of four exploring the future of how we govern and organise. Co-written by Sean Andrew, Louise Armstrong and Anna Birney

“Every attempt to write a new human story converges upon just one mundane, heartbreaking problem: How shall we come together, work together, create together? How shall we organise?”

Nilsson, Paddock and Temmink, 2021, Changing the way we change the world (Draft manuscript)

At the heart of change is how we think, relate and act. While these ways of being weave in and throughout our ordinary everyday experiences, they are not always given the intention and continuous attention they need. We believe how we relate, work together, and organise are cornerstones of change making. How we find ways to bring awareness to these elements really matters, and is easier said than done. They need just as much attention as the structural shifts that are required in the coming decade.

With this in mind, we are exploring governance as the place of untapped potential that can enable transformation today and into the future.

We’re defining governance as: The forms, structures and social processes that people and institutions use to create and shape their collective activities.

As such, we, and many others we’re working with and are inspired by (Beyond the Rules, The Hum, Reinventing Organizations, Going Horizontal, Practical Governance, Organization Unbound, Lankelly Chase, Shared Assets, Patterns for Change, Leadermorphosis and Barefoot Guide Connection, to name a few) are calling for governance approaches that reflect systemic principles that are suited for complex adaptive systems. Many of those we’ve listed are experimenting with elements of this, each adapting these to their contexts like Transition Movement and their shared governance approach, or CIVIC SQUARE, who are applying their mission and values into the organisational structures and processes – from how they do recruitment through to how they do financial planning.

We’re increasingly noticing internally, through our own organisational experience at Forum for the Future, and through our systems change strategy, collaboration and coaching work with others, that many of us subscribe to dominant forms of governance that are designed for a complicated, not complex world. We’ve noticed that sometimes, without intention, our own patterns of organising and those of many of our partners are perpetuating the structures, dynamics and patterns we are trying to shift. For example, we take centralised or hierarchical decision making approaches even though we want to enable greater ownership over a project which can come through taking advice-based decision making approaches where those closest to the challenge are part of the process.

Systemic governance on the other hand enables self-organisation (how a group of people organises their time, attention and resources in ways that meet the urgent necessity of the moment). It cultivates the emergent practices (and enables new system patterns) that help us align to regenerative and distributive approaches that better mimic our living systems.

Our inquiry into governance

After exploring new forms of organising, over the last 18 months at Forum we have been exploring two governance inquiry questions:

- What are the current governance approaches and ways of organising that are being used in attempts to create systems change?

- What would more systemic governance approaches for our work look/feel like and how might we transition to these?

To respond to these questions, we’ve been reflecting on our own organisational life while also learning from current and past collaborations we’ve convened or participated in over the past decade.

What is governance?

So how do people understand governance in their context? Through our inquiry we found that peoples’ understanding and expression of governance varied and was even sometimes quite vague. While governance meant different things to people, depending on their role or context, the people we spoke to talked about it in a few distinct ways, the ‘elements of governance’.

Elements of systemic governance

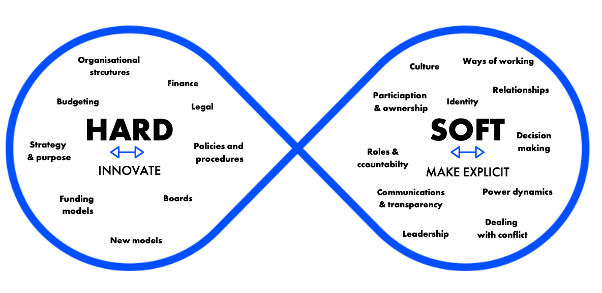

Systemic governance has both soft and hard elements.

Part of the reason why we tend to think of governance as a fixed process is that we often associate it with a few rigid components. From this exploration we realised that governance is in fact made up of a whole spectrum of elements, which while distinct, together create a unique governance context you may find yourself within, be that in an organisation, a movement, a collaborative endeavour, a community or really any place where people come together to organise something. By naming a spectrum of elements it expands the view of what governance is and how these parts form a tapestry.

We’ve created the figure 8 (below) as a summary of what we’ve heard, recognising that one way of distinguishing these elements is looking at the ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ elements. While the hard and soft elements can sometimes feel in tension with each other – they are in fact interdependent and together they form part of the governance landscape we have to traverse together;

In reality – we recognise these elements can be interchangeably hard/soft and are in symbiosis. Some will be visible and explicit and others invisible and implicit, depending on the context and people’s experience. For example, a “hard” element such as finance might actually be very hidden in an organisation without financial transparency or a “soft” element such as communication and transparency might be experienced overtly as lacking and be a visible gap in ways of working.

Innovating the hard and visible elements of governance

Most of the governance approaches we explored focused on the hard and often more visible, explicit structural elements of the organisation. These seemingly felt easier to figure out with clear problem > solution tactics. For these hard, visible structural elements of governance, people talked about inherited “best practices” that often took the form of compliance protocols. When working systemically, challenges can come when the ‘hard’ or ‘visible’ parts of governance are too rigid and fixed. We found that people working on complex challenges were often bound by these constraints and were yearning for ways to disrupt, reimagine, and innovate these ‘hard’ elements.

One hypothesis we are working with is that the hard stuff (the what) can be a transitory tool and a trojan horse for prioritising the soft stuff (the how).

The soft, invisible elements are the hardest part of governance to shift

The “soft” elements of governance are the implicit less formal cultural components of how people relate and organise. It’s often less tangible and thus harder to shift. Systemic governance is a constant practice of probing, sensing and responding to the dynamic nature of these elements in changing contexts. We found that these elements are too often submerged and therefore if we want to develop resilient adaptable governance approaches we need to bring to the surface and made explicit the soft cultural elements. While these elements are often deprioritised as they are unseen, they are still aspects of governance that materially impact the lived experience of people working within different organising forms.

Why is it so hard to work with the softer issues? The nature and quality of our relationships is the foundation of any governance. Questioning, challenging and reconfiguring established relationships is hard. It can take difficult conversations and processes to bring in different perspectives and overcome unhealthy power dynamics. Bringing self-awareness, paying attention to relational dynamics, creating space to listen and honestly share and transparent communications are the starting points.

Reframing governance as a journey

We heard people thinking about governance as putting structures and processes in place and thinking the rest will follow. Any of the words and connotations people mentioned pointed to governance as something that is fixed and hard, a static thing you set up on a one-off basis when in fact governance approaches are alive, can be enabling and need to be seen as a constantly evolving journey. We’ll explore some more of these governance myths in the next blog piece.

Sign up for the newsletter to get the next blog piece directly to your inbox.

Governance as an overlooked intervention or leverage point for change

These elements of governance play out in all of the many ways when we come together – be that in a multi stakeholder collaboration, across teams or functions in a large organisations, in communities, within networks or distributed movements. Governance is central to any form of organising or organisation creating change. We need to support others to imagine and implement new governance approaches that demonstrate and model how we can operate systemically, as a fractal of the change we are cultivating in the world.

What next?

We offer this figure 8 framework as a way to open up a different conversation about governance and acknowledge it is just one framing. We’d love to know if this resonates with your experience and how the challenges of hard and soft elements play out for you?

We’ll be writing two more pieces in this series. One to explore some of the governance myths we’ve been uncovering through our inquiry (e.g. governance helps us control things). And a second to dig deeper into some of the core systemic governance elements you might start to pay attention to now as critical yeast to influence your organisational practices and experience.

In 2021, we’re starting to explore some of these ideas with fellow travellers who have similar experiences in their context. If these ideas resonate with you or you want explore them more – get in touch with Sean s.andrew@forumforthefuture.org or Louise l.armstrong@forumforthefuture.org

Background context

At Forum for the Future, our governance inquiry is one of our three live inquiries (power, governance, regenerative) we’ve been exploring over the last 18months. This inquiry approach supports our aspiration to be a learning organisation that keeps questioning the assumptions nested in our purpose and supporting structures, processes and practices. Our belief is that these inquiries are helping us continuously become a system-changing organisation that is using our own experience as a site of learning, and as an expression of the change work we’re trying to do in the world. This inquiry has been greatly inspired and supported by those in the field who have been, and are, experimenting with ideas and approaches to governance. This piece is part of our ongoing Future of Sustainability series. In 2021 we’re exploring the narratives and practical interventions needed for transformation in the coming decade.

Read next:

- Exploring transformational governance together Governance can be transformational. When we set our sights on changing the world, we also know that governing well goes beyond preparing our own organisation, network or movement for the future. How do move beyond tweaking the way things currently work and apply governance to transform the ‘systems’ that operate in our society that maintain injustice, oppression and inequality (such as race, patriarchy and class)? (PART 2/4)

- Reimagining governance myths Part three in a series of four exploring the future of how we govern and organise. This piece looks at how people think governance happens today and challenge five commonly held governance myths. (PART 3/4)

- The governance flywheel In this final installment of our series on governance, we introduce the “governance flywheel”1 which highlights three fundamental linked areas that if they are deliberately seeded and nurtured, individually and together, can create the momentum needed to cultivate and grow healthy governance systems. (PART 4/4)

Originally published at Forum for the Future

An enabling, empathetic and courageous leader. I questions and challenges the way things are done, models what is possible and enable others to do that too. Sees potential and nurtures it in people and ideas. Living change while knowing how to strike how to strike the balance between adventure, rest, work and care and nurturing.

For another way of thinking about governance alternatives see Resonance Network's post and media toolkit : THIS IS HOW #WEGOVERN

The Web of Change

Creating Impact Through Networks

The following post is excerpted from the introduction of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change, now available in print, as an audiobook, and as an ebook.

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

— Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Since the beginning of our species, humans have formed networks. Our social networks grow whenever we introduce our friends to each other, when we move to a new town, or when we congregate around a shared set of beliefs. Social networks have shaped the course of history. Historian Niall Ferguson has noted that many of the biggest changes in history were catalyzed by networks—in part, because networks have been shown to be more creative and adaptable than hierarchical systems.[1]