Namrata (Nnaumrata) Arora

DEIB Consultant, Circle Convenor, Community Weaver, Certified Professional Coach, Workshop Leader, Writer, Changemaker, International Speaker, Systems Thinking Researcher and mom, Nnaumrata is the Founder of Enactive Systems (earlier Life Beyond Motherhood) and Zemyna Foundation, the Founding Director and Global Board Member for SCiO in India (Systems and Complexity in Organisations) and an empaneled Women’s Leadership coach with Heidrick and Struggles.

Laura Kaestele

Laura Kaestele is a network weaver, designer, facilitator, project coordinator, and grower focusing on integrative design, ecological regeneration, community and network development, permaculture, and holistic living with 10+ years of practical experience in the eco-social field. Together with colleagues from ECOLISE she works to cultivate a thriving impact network of community-led initiatives for climate change and sustainability in Europe guided by nature's principles, relationship building, and collaborative processes.

A Future for All of Us

October 31, 2022Transformation,Blog,Equity,Dismantle Racismequity,Systems Change,Immigrants

AN EXCERPT FROM RACE FORWARD'S REPORT ON PHASE 1 OF THE BUTTERFLY LAB FOR IMMIGRANT NARRATIVE STRATEGY

IN 2018, DURING THE HEIGHT OF THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION’S attacks on migrants, immigrants, and refugees, a landmark study warned pro-immigration forces that “attitudes towards immigrants and immigration are extremely complex: even those who appear to be pro-immigrant (who even think of themselves as pro-immigrant) are often very conflicted.”

A majority of Americans support the idea that migrants, immigrants, and refugees deserve to belong and thrive. Many recoiled from horrific images of family separation, violence against migrants at the border, and white nationalist violence against immigrants in cities like El Paso. Yet when the country locked down under the threat of the coronavirus and the Trump administration nearly shut down the entire immigration system, too few stood up to challenge these severe policies.

How does the pro-immigrant movement begin to confront such contradictions? To begin to answer this question, it might be better to look not to the tools of policy in the realm of traditional politics, but the tools of narrative in the realm of culture.

Cultural change precedes social change. Narrative drives policy. This is why we must be as strategic and rigorous in building narrative power as we are in building all other forms of power. Narrative is the space in which energies are activated to preserve a destructive system or build a better world for us all.

Right now, anti-immigrant forces continue to shape the dominant narratives around migrants, immigrants, and refugees, claiming that they are exploitable, expendable, criminal, and unworthy of equal treatment. These dominant narratives have fostered policies that terrorize migrants, immigrants, and refugees emotionally, economically, and physically. They protect a harmful status quo.

We are called instead to forge a new consensus. We must move a majority of people to imagine and act to create a world that does not yet exist. In order to make this world a reality, we need to orient ourselves toward the world we want to win, and make this future tangible and irresistible to a majority.

In this first phase of the Butterfly Lab for Immigrant Narrative Strategy, we hosted sixteen leaders to develop, test, and align narratives that meet our current political moment and advance our vision for the world we want to build. We supported their work with research,coaching, and funding. We were heartened by the many breakthroughs we made together.

Our work in the Butterfly Lab in this first phase affirms what we have known and gives us some directions to advance the movement towards more strategic alignment. We found:

• Nearly everyone believes immigrants deserve to belong and thrive.

• But many find it difficult to imagine an America in which that may be true.

• Core audiences respond well to all tested narratives, including those focused on shared humanity, compassion, dignity, and respect.

• But stretch audiences do not respond well to those aforementioned narratives. They do respond well to narratives of striving, responsibility, and liberty.

• Our narratives need to make sense of the past and present, and point toward immigration futures that are compelling to all.

Immigration remains the “third rail” of progressive politics. And yet, even in these discouraging times, we believe it is possible to win. When we look at the cultural transformations that other recent narrative movements—from “love is love” to #BlackLivesMatter—have made, we see pathways forward. Over a long period of time, many people built narrative infrastructures that could work in concert with policy infrastructures. When narrative power-building met the social moment, cultural inflection points turned policies previously thought unreasonable into ideas worthy of serious consideration. With immigration, we too must invest in narrative as key to winning power for migrants, immigrants, and refugees.

In this report, we share with you learnings, frameworks and tools, and insights into directions we can take to move forward together. Whether you are an advocate or artist, a long-time veteran of the culture wars or thinking about how to apply narrative or cultural strategy for the first time, this report is designed to work for you.

It is also designed to help you think and act at multiple scales—locally, regionally, or nationally—with rigor, alignment, and purpose. The best narrative strategy should foster a unity of intention with a diversity of voices, approaches, and methods. It should help people work together with a sense of alignment along different timelines and fronts. We want this report to be used to build skills, capacities, and networks within the movement, and, above all, to help all of us approach narrative strategically.

You can access the full report at Race Forward HERE or at Network Weaver HERE

You can also access a standalone version of the toolkit HERE

Race Forward catalyzes movement building for racial justice. In partnership with communities, organizations, and sectors, we build strategies to advance racial justice in our policies, institutions, and culture.

About the Butterfly Lab: Race Forward’s Butterfly Lab was launched in 2020 to build power for effective narratives that honor the humanity of migrants, refugees, and immigrants, and advance freedom and justice for all.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Liberatory Governance... and belonging

October 24, 2022Blog,Liberating Structues,Self-Organizing,Network Structure and Governance

How do we organize ourselves... in a world where everyone belongs?

Of the many barriers to living into a world where everyone belongs, this question feels fundamental: how do we organize ourselves? What might it look and feel like to work in an organization without coercion, without domination hierarchies… where everyone belongs?

So today I want to talk about governance. The term sounds bland, but I think it’s sexy: it is the magic that makes everything else possible, and the curse that can undermine even our best work if we don’t pay attention to it. I like this simple definition from the WeGovern community:

Governance is how we choose to be together.

Zen priest and movement strategist Norma Wong names what we all feel, looking out at the world, our institutions, and our movements:

Governance as it exists right now is in collapse.

While I think about governance at every level (family, organization, nation-state), today I want to focus on the scale of an organization, network, or collective: a group of people with a shared purpose and defined membership.

No transformation without governance

I want to thank Brandon Dubé in particular for pushing me, and Building Belonging, to embrace governance as a tool of transformation, and to explore sociocracy in particular. He helped remind us: if governance is about how we choose to be together, then by definition we are all involved in governance all the time, every day, in all of our relationships. Kali Akuno, one of the founders of Cooperation Jackson, agrees:

Governance is just how we make collective decisions together.

In a previous post reflecting on the nature of power, I adopted Priya Parker’s simple definition: “Power is decision-making.” Following this logic, governance is about making visible how power operates, and treating the question of how we wield power with intentionality.

I love Ted Rau’s delightfully provocative question and book: “Who decides… who decides?” If you really sit with it, it’s a radical question, and one that helps distinguish acts of leadership (someone has to speak first, to take responsibility for initiating or facilitating a conversation and the act of collaboration) from acts of domination (preventing others from speaking, my way or the highway, etc.).

Here’s the thing: I’ve come to believe that there is no durable path to transformation without attending to both the process and structure for how we make decisions together in a collective context. As Sean Andrew, Louise Armstrong and Anna Birney explain:

How we relate, work together, and organize are cornerstones of change making… Governance is central to any form of organizing or organization creating change.

We’ve been socialized to view governance as something annoying that gets in the way of “doing the work.” I want to flip this conventional understanding to expose a deeper truth: practicing good governance is the work; without it, anything we create will ultimately be fragile or even antithetical to our aims. As john powell reminds us:

If we don’t do things at a structural level, the structural level will undermine the progress we are making at the personal level.

What we agree on

To generalize broadly we can divide governance into two aspects: structure (think org charts, roles and decision-making authority, etc.) and process (how we make decisions, how we relate to each other). While the two are of course inseparable, today I want to focus primarily on structure: how do we embed the principles of liberatory governance in our org design?

Specifically, I want to distill three foundational principles that practitioners seem to agree on. Of course this is just my subjective perspective; I very much welcome generative pushback and other efforts to synthesize a broad and diverse field.

1. The opposite of coercion is consent

In a world where everyone belongs, we don’t want coercion. As Zakiyya Ismail notes:

Wherever there is coercion, there is oppression.

Dominant culture organizational hierarchies enshrine coercion: “bosses'“ are elevated above other workers; disobey your boss and you risk getting fired. In his beautiful handbook on Mutual Aid principles, Dean Spade notes:

Our society runs on coercion… Most of us have little experience in groups where everyone gets to make decisions together, because our schools, homes, workplaces, congregations, and other groups are mostly run as [domination] hierarchies.

Because we lack practice, too often when we seek refuge from this authoritarian model we make the mistake of swinging to the opposite extremes: either rejecting structure altogether (all hierarchy is bad! inevitably leading to the infamous “tyranny of structurelessness”) or demanding an overly rigid homogeneity that calls for universal consensus. As experiments like Occupy Wall Street have shown, relying only on consensus (everyone agrees on the way forward) is both inefficient and can allow bad-faith actors to impede progress… itself a form of coercion.

The antidote is consent-based governance. As Stas Schmiedt notes:

Consent is how we operationalize liberation.

There are a range of methodologies emerging that seek to codify what a consent-based governance structure/practice might look like; my favorite thus far is sociocracy, a concept given life by the team at Sociocracy for All. This article by Ted Rau is a great introduction, and here is a helpful companion piece distinguishing consensus-based governance from consent-based governance. To be clear: majoritarian democracy (what we purport to practice in the United States) is NOT based on consent. Majority rule doesn’t seek to integrate minority objections; it seeks to overrule them: in my view, that is a coercive system.

The core idea is that the bar for action is not agreement but willingness (a term I prefer to “tolerance”). People can (and must!) object to a proposal that they believe will undermine organizational purpose, but that objection is not a veto: it’s naming an issue that must be addressed and integrated into an improved proposal before it can move forward. The assumption is that the proposal will move forward once the objection has been integrated.

It’s a subtle but radical shift that provides the basis for everything that follows. As the folks at Circle Forward note:

Consent is the foundation for an entire governance system.

2. Structure codifies, reflects, and creates culture

OK, we’re organizing around consent: this is already a radical departure from dominant cultures (and organizational structures) predicated on coercion. But precisely because we have so little practice/training in operationalizing consent, we need help. Our structures have to support us, individually and collectively, in practicing different ways of being. In his comprehensive study about how change happens, sociologist Damon Centola concludes:

We don't make decisions as individuals; we are reciprocally influenced by the environment and people around us… It is largely the structures in which they are embedded that determines whether things work well or not.

On this all the practitioners I follow agree: the structure both reflects and creates culture; it serves to codify how we relate to each other. Tracy Kunkler explains:

Governance is how we set up systems to live our values, and leads to the creation, reinforcement, or reproduction of social norms and institutions. Governance systems give form to the culture’s power relationships.

The folks at Brave New Work name the implication for our org structures:

Whatever we want to be true about the way we relate, is it in the system, is it in the structure?

Taking this question seriously underscores the importance of governance. If we acknowledge that our default patterning is shaped by systems of oppression (white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, etc.), then without intentional effort—and lots of practice!—we are likely to repeat those patterns in our organizations. bell hooks names the challenge:

To build community requires vigilant awareness of the work we must continually do to undermine all the socialization that leads us to behave in ways that perpetuate domination.

Without a structure that supports us in practicing these more liberatory ways of being, we will find ourselves struggling. I love this vulnerable share from Dana Kawaoka-Chen documenting her own efforts at culture-change inside her organization:

Even if I as the executive director had a vision for another way of being, I did not have the organizational structure in place to reinforce a different set of values, which allowed the default operating system to prevail.

3. We want a decentralized structure that enables people to share their fullest gifts

Here we begin to wade into murky waters. I think practitioners generally agree on three things:

- Liberatory governance systems must be decentralized: there is no central command and control structure.

- The structure must seek to, as Alanna Irving notes, “align power with responsibility.” And I would go one step farther: to align responsibility with authority: whoever is best-positioned to act (as a function of the healthy expression of power, whether derived from knowledge, capacity, or relationships) has the responsibility and authority to act.

- The structure must help maximize and channel “discretionary energy” in service of our shared purpose. (Indeed, this has long been one of my core definitions of leadership: the ability to inspire and support others in tapping into the fullest expression of their gifts… and sharing those gifts in support of the collective).

Emergent paradigms seek to solve for these concerns; frameworks like sociocracy do a good job of speaking to the first two points here. While in theory sociocracy can also provide a structure to unlock and channel people’s gifts, I have yet to see it work like that in practice… for reasons I’ll get into below.

Where we still struggle

There is so much that is difficult about this… even as the promise remains tantalizing and delightful when we taste it. As Ericka Stallings notes,

This lack of knowledge about how to operationalize liberatory values exists because we’ve never actually experienced it, so we are almost imagining it into being.

I want to name here three of the core challenges I see that we haven’t yet collectively found a way to effectively navigate. These are areas of experimentation and practice in real time among all the organizations, networks, communities, and collectives that I see on the cutting edge of this work (groups like Wildseed Society, Change Elemental, Resonance Network, the Fierce Vulnerability Network, the Post-Growth Institute, the Thrive Network, and Open Collective, among others).

1. Leadership, agency, power, and self-governance (structure alone will not set us free)

There are books written on each of these topics, but the dynamic I want to highlight here turns on the question of agency (defined as the capacity to exert power).

The general pattern I observe splits along lines of privilege and marginalization. Those socialized into power and privilege, once they become aware of that socialization and not wanting inadvertently to perpetuate domination, shrink from exercising their power: they abdicate their agency (white people in multiracial space, e.g.) At the same time, people marginalized and oppressed by dominant culture have a hard time feeling safe enough to exercise their rightful power. Everyone is afraid to take on the responsibility that comes with leadership, especially amid the radical complexity of proposing a course through uncharted waters… and make decisions that will inevitably have an impact on other people.

The result can be a leadership vacuum, where no one is taking the action that all can see is needed. Gopal Dayaneni names this as one the biggest obstacles we face on the path to liberation:

The primary barrier is our ability to democratically self-govern… The practice of self-governance is the hardest thing. We have to make the hardest decisions, and we don’t have any practice.

Instead, we often look to the structure, or to others with more visible forms of social, positional, or structural power, to get us unstuck. But this misses the point. Quanita Roberson offers this provocation:

So much of what we are struggling with as a culture is that we want everything to be external so that we don't have to take responsibility for what is actually ours to do.

Norma Wong puts it simply: “Transformation requires agency.”

Self-organizing is dead: long live self-organizing!

So here’s the paradox. On the one hand, I agree with Gopal Dayaneni, who declares:

The future must be self-organized.

And I agree with Alanna Irving, who asserts:

I believe there is no such thing as “self-organizing”—there is always work to be done and a skillset required to coordinate people to move together toward a larger shared goal.

The challenge I’m naming here has to do with coming into right relationship with power: our own, others’, and power as made visible and reflected in organizational structure. For self-organizing to work, individuals have to assert agency: to take responsibility for making decisions with and on behalf of the collective. This is by definition an act of leadership. Nwamaka Agbo frames the challenge:

We don’t what it means to lead, until we have to make difficult decisions and take accountability and responsibility for those decisions… collective decision-making still requires that we make decisions.

2. We don’t know what to do with money

If power, agency, and self-governance is hard… that difficulty increases by a degree of magnitude when we introduce money. Two things were clear to me in launching Building Belonging: I wanted to avoid the funder-appeasement / movement-capture trap of the nonprofit industrial complex; and I wanted to avoid the opposite extreme of relying entirely on a volunteer-based community without any money. Both situations risk reinforcing the very power dynamics I want to escape: the gatekeeper model of elite access to funding, or volunteer networks that end up becoming becoming playgrounds for the privileged.

And there’s more: I had a sense that money is one of the most transformative realms of practice available to us; as Orland Bishop reminds us, it is humanity’s largest unconscious agreement.

I love this entire interview with Gopal Dayaneni, where he explains:

The primary reason people pay their rent is because they have no alternative ways to meet their housing needs… It’s not primarily the coercive power of the state or corporations. Rather, we are forced to comply without consent because we have no meaningful alternative.

So even as we focus on developing more liberatory ways of working with money (gotta pay rent!), that’s only half the work: we also have to be devoting energy to meeting our individual and collective needs outside of that system. If we are to transition to a post-capitalist world where everyone belongs, here’s what feels clear to me.

- We have to find ways to meet our needs outside of the money/exchange paradigm (see e.g. this recent post from Mike Strode, exploring some creative ways of flowing value and meeting needs outside the bounded system of money)

- We have to use money to meet our needs in the interim while we remain tethered to that paradigm (see e.g. this discussion of challenges and experiments from Francesca Pick)

- We have to be proactively engaged in both levels at the same time (I love this example from the DisCO cooperative: finding ways to honor the value not only of traditionally remunerative work but also of care work and pro bono contributions)

I’d love to see more examples like DisCO intentionally exploring this space, anchored in indigenous and intersectional feminist principles.

3. Navigating conflict and impact

On this point Kazu Haga is blunt:

The greatest barrier to living and building beloved community is how we navigate conflict.

He may be right: everything else is navigable if we have the skills to transform conflict; not much is possible if we don’t. This has been my consistent lesson from all my work understanding and trying to transform oppressive systems: they depend on separation. Oppressive systems cannot sustain themselves if we have the ability to repair ruptures and reconnect what has been severed. Indeed, I love this definition of leadership from Marcella Bremer, channeling Otto Scharmer:

Leadership is connecting what was separated.

How can we embed accountability and conflict transformation in our structures, when these are fundamentally relational capacities? As Sean, Louise, and Anna remind us:

The nature and quality of our relationships is the foundation of any governance.

I don’t have great answers here. It feels clear to me that a big piece of the work is re-wiring how we understand and relate to conflict: from something bad to be avoided, to Malidoma Somé’s beautiful definition:

Conflict is the spirit of the relationship asking itself to deepen.

My own evolving sense is at minimum every organization/network/collective needs two things:

- The structural equivalent of a help line: where do you go when you find yourself in conflict and unsure how to proceed? I love Alyson Ewald’s idea (from this podcast) of creating a “conflict celebration team.”

- A community-wide commitment to building capacity to navigate conflict, individually, interpersonally, and collectively. This includes trainings and practice, drawing on a growing range of methodologies (I like the framework offered by Deep Democracy, and the skillsets named in Nonviolent Communication, e.g.)

And of course, to name the elephant in the room here: upstream of everything we’re working on is trauma. If we want to come into right relationship with power and agency, hold the tension of navigating money as we transition toward post-capitalism, and transform conflict… we need to find ways individually and collectively to heal from trauma.

Structure is not a panacea. We are still human beings inside of whatever structure we create, with all of our foibles, unhealed trauma, and limited capacity. I’ve written elsewhere about trauma, but need to name it here.

An invitation to practice

If you made it this far, I want to close with an invitation to action, and to feedback: what resonates? What doesn’t? What are you seeing? This work is incredibly difficult… and incredibly liberating, when we find ourselves in structures of belonging.

The WeGovern Community reminds us:

Governance begins with each of us: in practice, in relationship, every day.

I like the way Kim Tallbear expresses our humble aspiration:

We are not trying to get it right, we are trying to get it less wrong, through practice.

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at building belonging

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Getting to the Goods (and Beyond “Folded Arms” Syndrome) in Impact Networks

October 17, 2022Uncategorized,Network Weaving,Transformation,Blog,TransformationEquity,Systems Change,networks

“Your generosity is more important than your perfection.”

Seth Godin

Over the past 20 years of working with a variety of social change networks, I have observed a common dynamic surface after the initial enthusiasm and launch phase. As happened recently with a place-based network about a year into its development (navigating COVID and political uprisings along the way), some members started to bang the “What have we actually done?” drum. Contextual crises notwithstanding, this is not an inappropriate or unhelpful question. As important as relationship and trust-building is, there can come a time when people want to know … “So what?” Sometimes this comes from what we might call more “results-oriented” people in the network. Or it may come from the more time-strapped and stressed, those from smaller organizations, or those who just genuinely don’t see the return on their investment. When this has come up, and people are either holding back (“folded arms”) or threatening to walk, I have witnessed and facilitated several different ways of moving through the real or perceived lack of progress.

- “If you want it, then you better put a ring around it” – In one instance, the convening team of a state-wide network essentially drew a line around all of the network participants and started claiming their successes as network successes. This might sound a bit shady, though it was not done in that spirit. By celebrating “your success as our success,” people felt appreciated and started to turn towards one another and see themselves as a bigger we. They didn’t have to wait to get to mass action. Smaller subsets having success counted.

- Get a quick win – In another state-wide network, fraught at the outset by folded arms despite the fact that people would regularly physically show up for meetings, a network coordinator seized upon a timely policy advocacy opportunity that surfaced, which resulted in a mass outpouring and a legislative win. Nothing sells like success. That early victory got people eager to see what else they might be able to accomplish and they settled in for some more relationship-building.

- Collect and share connection stories – We know that relationship-building is not just about the relationships. It can lead to new partnerships and projects. Often this happens at the start of a network, but is not tracked. We worked with another place-based network that intentionally set out to track the results of connections made in and through the network, and then shared these with the network as a whole. More about connection stories here.

- Highlight the unusual and adjacent conversations – What makes many of the networks we work with unique is that they bring together people who do not often work with each other. Highlighting this and also what emerges out of novel interactions across fields can make “just talking” into exciting explorations and engines of innovation. For a little inspiration on this front, see “Why the most interesting ideas happen at the borders between disciplines” from Steven Johnson at Adjacent Possible (!).

- Pump people up, individually and collectively – Let’s face it, in these times (and really all times), expressing genuine appreciation can go a long way. We work with a network convenor who does this wonderfully, tracking and celebrating people for their individual contributions outside of network gatherings, and constantly speaking to the power and potential of the collective. She just makes people feel good! This can make the proverbial “marathon, not a sprint” more enjoyable.

- Get a super weaver going – Having a really adept and energetic network weaver can make all the difference in the early stages of a network. We have seen the impact this can have when ample capacity is created to regularly check in with people, listen to them, make connections between different needs and offers in the system, and encourage people to share more with one another. When those exchanges start happening, the “there” there is often more apparent.

- Lift up the network champions – Generally there is a small group of people who really appreciate and lean into the value of the network from the get go (gratefully receiving and using resources that are shared, following up with new connections, testing out new ideas, leveraging the network as a platform), making it happen and not waiting for it. Observing this, capturing it, and sharing it with the network can help make the point that the network is what people make of it and give ideas for how to make this happen.

What have you done to successfully navigate impatience and intransigence in impact networks?

About the Author:

Much of Curtis Ogden's work with IISC entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food public health, education, and economic development systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Co-designing a platform for self-organizing networks

How do you know who is in your network? How do you find people who are interested in similar topics or actions? How do you know your network is making a difference? How does your network support self-organizing?

These are some of the questions about communications and platforms in networks that Ari Sahagún and June Holley will discuss in this upcoming session on November 3rd. Ari will give a demo of the Rhizome platform - an innovative platform designed for and with networks that provides weavers with real-time data about the network. June will demonstrate how mobilizing network weavers to co-design a platform can result in a vibrant, engaged and self-organizing network. The bigger vision underlying our work is to support network weavers more holistically, co-creating learning and practice spaces together to support their networks. There will be plenty of time for discussion and questions.

This session will be useful for any network exploring possible platforms for their network, but we are hoping that some of you may want to join us in a 6-month platform co-design process.

We are looking for up to 5 networks who fit the criteria and can contribute $5,000 - $10,000 for their involvement in the use and co-design of the Rhizome platform and practice sessions. We will have an equity scholarship for one group who cannot contribute at this time.

Nov 3 // 9a Pacific / 10a CDMX / 12n Eastern / 5p CET

1 hr, stay after for Q&A

Register for this session here.

Here are some screenshots from Rhizome

Part of a Dashboard

Criteria for self-organizing networks we want to work with

- Have been in operation for some time (not new/nascent network)

- Have a sense of what the network is

- Have considered questions of network infrastructure (ex. governance, resource sharing, etc) - not necessarily have it figured out

- Have active and engaged network members

- Has self-organizing or collaborative projects or ready to form them

- Have some background knowledge of self-organizing or willing to put in time to learn

- Has staff or a leadership group willing to put in an hour or two every week to plan with us

- Attempting to live into network values (embracing uncertainty, practicing decentralization, co-design/participation)

- Have substantial number of participants who have been marginalized (BIPOC, global south, youth, etc)

- Seeking transformation and/or building alternatives (economics, justice, etc)

Strengthening Social Connection and Opportunities in Rural Communities

October 14, 2022Community,Network Support Structures,Transformation,Blog,equitySystems Change,Collaboration

This brief describes an unfolding learning journey intended to strengthen social connection, resident voice, and agency to address inequities in rural health and well-being. Along the way, we have come to realize the important lessons for each of our institutions and ways in which we are better off for having taken this approach to our work.

At St. David’s Foundation, we believe that realizing health equity to minimize the consequences of poverty and racism reflected in the social determinants of health is foundational in our work in Central Texas. Rural communities are dramatically under-represented in philanthropic investments nationwide and in Texas, and the Foundation’s own balance of investments skews toward initiatives that serve urban populations. When philanthropic dollars are invested in rural communities, they are typically directed to the few established nonprofits and local government entities that implement programs or provide services to residents. Community members, especially people experiencing vulnerability and isolation, are rarely asked what they need to improve their health and quality of life and how they may utilize the power inherent in their communities to contribute to those improvements. The most common observation from the philanthropic sector is that “these residents” are rarely poised to receive and control funds to work on the issues they believe are most important for the health and well-being of their own community. Listening and enabling capacity can change that.

Listening to our Rural Neighbors

After a sustained period of building deeper ties and stronger relationships in our rural communities surrounding Austin and Travis County, the Foundation learned that many of our rural neighbors felt disconnected from and ignored by the Foundation and local decisionmakers in their communities who decide how resources are prioritized and distributed to address community needs. Residents from the surrounding rural counties of Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays, and eastern Williamson County expressed an interest in working with the Foundation and their peers on priority concerns including youth, mental health and substance use and misuse, food insecurity, and affordable housing.

Community Capacity Building and Enabling as Rural Strategy

In partnership with The Strategy Group (TSG), a national consulting firm with expertise in catalyzing resident-led community networks focused on health and well-being, the Foundation invested in community capacity building (CCB) strategies to engage interested residents in working collaboratively on issues of importance to community members and enable their inherent power to participate in problem solving.

Informed by residents, the Foundation and TSG co-designed an approach that incorporated key community capacity building outcomes so that residents could develop their own solutions to pressing self-identified community health concerns. TSG also offered a process for the Foundation to build its own capacity to invest differently in rural communities— an approach that invested in network infrastructure, resident leadership development, nonprofit leadership to partner with and support community networks, and connected people experiencing vulnerability and lack of connection to opportunities for community development.

The Foundation’s rural strategy centered social impact networks (Plastrik et al 2014), network weaving (Holley 2012), and sustained community engagement to create an expanding, diverse, inclusive resident-led network focused on health and wellbeing -inequities often reinforced by historical and structural legacies of exclusion and privilege. Stuart (2014) notes, “this is one of those cases where a commitment to social justice is crucial. It is important to consider who is included in the “community” that is leading the process. Who is excluded from community leadership? Whose voices are missing from community debate? Whose interests are being served?”

And if the community is driving decisions about their own development, what does that mean for how the Foundation should be investing in community?

Centering Equity and Equitable Opportunity

As St. David’s Foundation has embraced and prioritized health equity, rural investments evolved to become more place-based and community-focused. How the Foundation showed up in the community (and how frequently), how grant opportunities were presented, and how funds were distributed when CCB was the overarching purpose changed the nature of the relationship between funder and community. In our rural work, the Foundation recognized that a portion of our rural investment needed to give the community control over decisions and resources to determine what resources were needed to spur or make lasting change.

Bringing it all Together in Central Texas

The community network approach in Central Texas prioritizes:

- Centering the voices and lived experiences of rural BIPOC residents (equitable opportunity);

- Seeding a network of interested resident leaders who have a deep understanding of their and their neighbors’ needs to direct their own community development work; creating new relationships; and offering new ways of working, thinking and leading in community; (i.e., social impact networks);

- Engaging and supporting local residents to organize themselves to work on projects that move the community from talking about problems to taking action on problems (i.e., self-organizing);

- Supporting residents who want to develop the leadership skills to engage other residents to work together in a resident-led network focused on health and wellbeing (i.e., network weavers); and

- Putting a pool of resources into the hands of those who have the lived experiences of health inequity, poverty, social isolation; are closest to community problems; and who want to work with their peers to improve community health and wellbeing from a solidarity stance.

What are Networks and Network Weavers?

Social impact networks (like the ones emerging in Central Texas) are constellations of people, organizations, and communities connected by a shared purpose to make change. In the Central Texas network, there is a high-level purpose to improve the health and wellbeing of residents in the region.

Network weavers are residents in the Foundation’s rural service area who have chosen to be a leader in the network; they are the “engines” of our regional network. Weavers strategically connect other residents, convene groups of interested residents, coordinate small projects aligned with resident interests and needs, and work to grow the network and the projects the network is interested in pursuing. Holley (2012) describes a network weaver as “someone who is aware of the networks around them and explicitly works to make them healthier. Network weavers do this by helping people identify their interests and challenges, connecting people strategically where there’s potential for mutual benefit, and serving as a catalyst for self-organizing groups.”

The Foundation provides operating support for TSG as well as funds to support network infrastructure (e.g., communications, evaluation, training, storytelling), stipends for weaver leaders, and shared gifting circles. To date, over 100 residents have been trained to be network weavers in Central Texas.

Building Community Leadership

The Foundation’s investment in community capacity building by catalyzing resident-led networks and training residents to become network weavers is designed to engage and support residents to contribute their time and talents (i.e., community leadership) to solve pressing self-determined health and wellbeing challenges in their own communities. Residents also participate in monthly peer assist sessions which enable real-time feedback and advice from peers as they practice their leadership skills.

Participatory Grantmaking

Using participatory grantmaking processes and resources, network weavers are supported to identify local problems and then work collaboratively with other residents to co-design and test solutions. Shared gifting emerged as an important participatory grantmaking tool to support weavers during the second year of project implementation. We asked ourselves: “how can a small pool of grant funds be used to foster connection across different communities and authentic collaboration, rather than competition?” Shared gifting allows residents to decide what the most urgent community needs are, rather than the Foundation, and then to grant dollars to community projects they wish to support. There are no required outcomes of the process other than what is determined by the participants during the shared gifting process.

From participant reports of the shared gifting process, we were excited to learn that a shift in control of grant funds from the Foundation to the group of network weavers (residents) created an environment of social connection, equity, encouragement and support, feelings of abundance, and community. The typical grantmaking experience of competition and scarcity often experienced by potential grantees when responding to competitive grant opportunities was not reported by participants. Instead, weavers were excited to make new connections with other weavers, hear about new projects happening in their community, extend offers of time, talent, and treasure to other weavers, and expressed pride to be able to support those projects with the resources they controlled.

Conclusion

Residents who have participated in network weaving and participatory grantmaking have shared a common experience of personal and professional transformation, social connection, empowerment, and awareness of new possibilities and promise for their communities. The Foundation’s experience of investing in rural communities and its people by creating opportunities for resident decision making about how resources should be directed to pressing issues in their communities has revealed new possibilities for grantmaking and use of our social capital to advance the health and wellbeing of rural residents in Central Texas. Further, the experience with weavers as grantmakers underscores the importance and urgency of integrating community voice consistently in the Foundation’s equity-driven journey.

Voices and Learnings

Network weavers were invited to share their thoughts on how weaving has influenced their personal and professional lives. The themes found in their comments were that network weaving:

- Offers both professional and personal value to persons.

- Provides a framework that is valuable to tackle complex community issues.

- Facilitates making connections that create change in the community.

- Allows the use of shared gifting as a unique learning, connecting, and growing experience.

- Fosters among network weavers a desire to build new skills and capacities to continue to strengthen their work within their own communities.

- Encourages persons who had existing networks to make those networks more effective, efficient, and stronger by implementing what they learned in the Network Weaving learning opportunity.

“Weaving has tremendous value as it has empowered me to create with others outside of my usual network, helping to expand my reach and capacity to support others.“

“Throughout the past few years, in a mid-COVID society, Network Weaving has proven to be a skill set and collective necessity to maintain community collaboration. As work-life has evolved and more individuals experience isolation, Network Weaving has made the ability to connect (in-person or virtual) a go-to process for me in my personal and work life.“

Krystal Grimes, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Ultimately, all of us have the same end goal of building a better community. We all are here for the same reason; we’re all doing this work because we have a passion for community building. And network weaving has really given us that opportunity.”

“It has given me a really clear framework for what I’m doing. It’s not something that lives in my brain. Now. it’s an actual process and an actual framework that I can utilize to share information.”

Elizabeth Marzec, 2021, Organizational Leader, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Helping the community that you live in, helps you, it helps your children and helps your grandchildren. So, I think that is the point in the future that weaving really impacts.”

Linda Quiroz, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Bringing leaders together, making community change, and having people who never thought of themselves as a leader know that they can all make a difference. I love that.”

Kathleen Moore, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Prior to network weaving, I had no idea how to get this passion, this idea realized . . . I’m trying to be involved in the community. But I needed direction. I needed ideas, I needed strategies. And so, when I was invited [to learn about network weaving], it gave me what really felt like a breath of fresh air, because I’m going to be around peers that can help me along the way. And then also for me to help others.”

Sonya Hosey, 2021, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“I think about the word power. And that power is shared. It doesn’t belong to one person or group . . . and I love that about network weaving,”

“I have watched the whole design of network weaving just open this road for people to speak and share and dream, and nothing is impossible”

Maureen Stanek, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

References

Holley, J. (2012). Network weaver handbook: A guide to transformational networks. Athens, OH: Network Weaving Publishing.

Moore, W. P., Klem, A.M., Holmes, C.L., Holley, J. and Houchen, C. (2016). Community innovation network framework: A model for reshaping community identity, The Foundation Review, 8(3). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1311.

Plastrik, P., Taylor, M., and Cleveland, J. (2014). Connecting to change the world: Harnessing the power of networks for social impact. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Stuart, G. (Apr 10, 2014). What is Community Capacity Building? Impact Initiative.

Abena Asante has over twenty years’ experience in philanthropy, public health, and the nonprofit sector. A senior program officer at St David’s Foundation, she leads efforts that catalyze community action around issues and opportunities that align with the Foundation’s firm commitment to achieve health equity.

Dr. William Moore is Principal at The Strategy Group, a Kansas City-based international consulting firm supporting nonprofits, foundations, and communities. Bill is a Senior Fellow at the Midwest Center for Nonprofit Leadership at the University of Missouri – Kansas City, Senior Associate for Rural Health at the Texas Health Institute, and is the rural health advisor to the St. David’s Foundation.

originally published at gih.org

A in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and studied at Sciences Po, Paris as an Erasmus scholar.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Community engagement: How to create meaningful connections in an age of distrust

October 4, 2022Network Weaving,Network Support Structures,TransformationBlog,Systems Change,Collaboration,Community

Community engagement is a term applied in various contexts, often meaning different things to different audiences. It is sometimes used interchangeably with other concepts such as community outreach or community consultation. For the purpose of this article, we utilise the term community engagement to describe a process where local government, charities, and funders collaborate meaningfully with the communities that they serve.

The insights presented in the following text are informed by our experiences working with the above groups. We hope this article is particularly useful to those who are hoping to build stronger and better-informed relationships with their communities.

Community engagement

Community engagement is a key part of any project or programme that seeks to directly enhance the lives of the public. When providing services that affect people belonging to a defined area or group, building relationships within that community is a non-negotiable. Whether you’re a charity, funder or government authority, understanding what communities are thinking and feeling, and taking those thoughts and feelings seriously, is the only road to a legitimate and meaningful partnership.

What is community engagement?

Why is community engagement important?

How should I approach community engagement?

Download The Community Engagement Canvas [Free Resource]

What is community engagement?

Community engagement is all about supporting communities to take ownership of the resources that are available to them. This means taking an active role in creating partnerships between the institution that is providing those resources, such as a local council or charity, and the communities that will be receiving them. Grassroots, voluntary and faith organisations as well as mutual aid groups are deeply embedded in their communities and have a great understanding of local dynamics. This is what makes them such important partners for service providers.

In the simplest sense, community engagement is likely to involve connecting with community leaders and facilitating conversations about what they would like to see happen in their communities. This might look like restoring public spaces such as libraries or a community garden, engaging in discussions around improving housing standards or planning and programming a community event.

Why is community engagement important?

Over the last two decades, trust in ‘big’ institutions has been in a state of flux. Historical events such as Brexit and more recently COVID-19 have shifted our understanding of public life and how we relate to the institutions and organisations that shape it. The latest British Social Attitudes Survey reported that only 23% of people trust the government to put the needs of the nation before the interests of their party. So, how can those with institutional power begin to build back trust with the communities that they serve?

An approach gathering momentum in the US termed ‘earned legitimacy‘ puts forward the argument that it is the role of public institutions to build bridges with communities who have lost faith in their ability to serve. More specifically, it suggests that a public institutions’ legitimacy hangs directly on how much their community trusts them to act justly on their behalf.

Government might be a useful example to illustrate the meaning of earned legitimacy, but we believe that this approach is a solid one for any organisation that has the power, resource and will to engage communities in their activities. In short, it’s on you to put the work in.

How should I approach community engagement?

1. Get real about the role of history

When you work for a long-established organisation with substantial control over wealth and resource, people are likely to have pre-existing ideas about what you do and how you do it. Historically, many communities have been underserved and even harmed by powerful institutions. We see examples of this frequently in the news, whether it’s black individuals being more likely to be subject to stop and search or international charities such as Oxfam’s failure in preventing abuses of power. It makes sense that some communities are sceptical to work with those that have represented racism, mistreatment and harm to them in the past.

‘What are your concerns about this organisation and is there anything we can do to reassure you?’

The Centre for Public Impact recently released a report on how they went about restoring trust between Americans and local government by working with local communities in four different parts of the US. This involved “acknowledging past wrongs and showing a commitment to confront[ing] present-day […] issues.” The report highlights how important it is for historical tensions to be addressed with openness and honesty, especially in the early stages of relationship-building. This may involve asking community members questions such as ‘How do you feel about working with us?’ or ‘What are your concerns about this organisation and is there anything we can do to reassure you?’ before embarking on a shared venture.

2. Recognise that expertise exists within communities

The starting point for community engagement should almost always be that nobody understands what a community wants and needs better than the people belonging to the defined group. Big institutions often work with experts and consultants to problem solve and generate solutions. The Social Change Agency believe that the answers exist within communities and it’s really about creating safe spaces where those insights can be shared. If you are engaging communities in a consultation process, it’s worth considering that individuals should be paid for their time. They’re the real experts.

3. Getting to know each other is work too

With deadlines, budget restraints and the pressure to demonstrate outcomes, we often want to skip small talk and get right to the finished product. If you have the power to write ‘getting to know each other’ time into your project plan, this could really support relationship-building with your community and will almost definitely make things more efficient in the long run. Taking the time to visit the people you’re hoping to engage with and really understanding what motivates them can help to create the conditions for a durable partnership.

4. Communication, communication, communication

Whether it’s email, Slack, WhatsApp or Facebook, the way we interact often shifts depending on audience and urgency. This is no different when we are engaging with community networks. If barriers to communication emerge, it can drastically affect your relationship and slow down the pace of delivery. At the very beginning of your community engagement endeavour, ask community members how they would like to be contacted and what is most convenient for them. Make it as easy as possible to connect but create boundaries around how often and when is appropriate to communicate. This will give you a solid vehicle via which collaboration can flourish.

5. Defining success together

What success looks like to communities and what success looks like to funders, governments and charities are often two entirely things. Success to a local authority might be engaging 20 different community groups in a consultation process before opening a new digital community hub. Community members may visualise success as guaranteeing this space is free to use for certain age groups.

A way of define shared success might be creating an accessible and affordable digital hub designed by and for the community. It’s worth having a conversation about what both of your ambitions are for working together and creating a sense of shared purpose in your collaboration. Establishing a common goal is likely to keep you connected as you move through the logistics of delivery.

originally published at Social Change Agency

Maisie Palmer 's interests lie in social innovation, education, and supporting community-led movements. Prior to joining our consultancy team, she was National Programme Lead for Education at The Roots Programme where she designed and delivered an exchange programme tackling social division amongst British youth. Maisie founded Mxogyny an online and print publication for marginalised creatives. She has also worked for the Secretary of State for Scotland and the International Criminal Court. Maisie holds an MA in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and studied at Sciences Po, Paris as an Erasmus scholar.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Reframing Power and Embracing What is Possible

September 26, 2022Blog,Systems Change,GovernanceSystems Change,Reframing Power,Reflection and Learning,Transformation

Lighting the Candle of Liberatory Governance

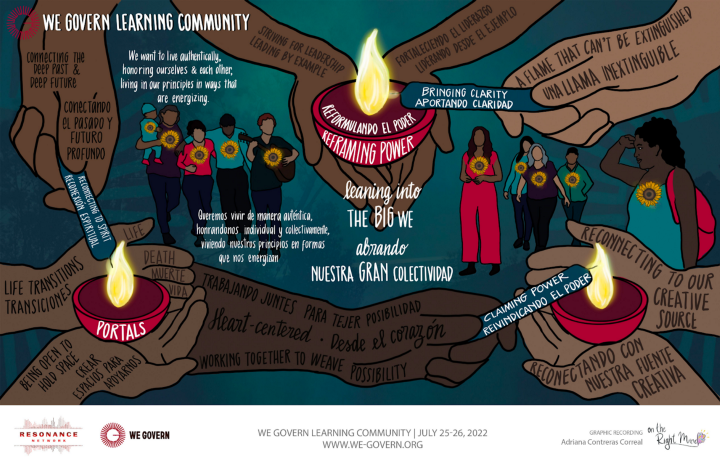

As phase two of the WeGovern Learning Community winds to a close, participants gathered to reflect on their journey.

This community came together with a shared commitment to practice liberatory governance — and we did. Participants—including Resonance Network, who convened the learning community space but practiced as a participant team—reimagined what governance beyond dominant power structures could look like in our organizations, tribes, networks, and teams.

And what came through as we reflected on the experience was not only the transformations that took shape externally within these groups, but internally among participants as well.

Our choices add up to the world we’re building — and once you feel the power and possibility in choice making and community building from a place of liberation and care, you can’t turn back. We all felt that.

Our commitment to governance practice kindled a deeply felt sense of what is possible.

The process of embracing WeGovern—a set of governance principles rooted in mutual care, dignity, and thriving–in our own lives—helped each of us realize that we have more agency in the choices we make to live from our values than we realized.

Of course, the systems of control and domination we live within want us to believe that power exists outside of ourselves — but the opposite is true. Our choices add up to the world we’re building — and once you feel the power and possibility in choice making and community building from a place of liberation and care, you can’t turn back. We all felt that.

This practice became an affirmation that governance begins with each of us — in the choices we make each day to engage with ourselves, each other, our families, and our communities.

Bringing clarity

Each of us felt this sacred responsibility — an embodied knowing that developed in the practice. We described it as “a bell that can’t be un-rung” or similarly, “a flame that can’t be extinguished.” Once we felt that sense of agency in choice making — and began to witness the ripple effect of transformation in our communities — we couldn’t go back to business as usual.

But the future we are moving toward isn’t completely unknown to us — it lives in our lineage, in the memories of our ancestors, in the wisdom of the land that sustains us, and in the relationships we are building with one another.

Instead, we find ourselves choosing to move into the unknown — away from what has been familiar, and toward what feels whole. The future we are moving toward is unknown — it is unknown to the collective systems we live within that have shaped so much of our lives, profited from limiting our perceptions of possibility, and capitalized on dulling our sense of collective purpose. But the future we are moving toward isn’t completely unknown to us — it lives in our lineage, in the memories of our ancestors, in the wisdom of the land that sustains us, and in the relationships we are building with one another.

Reconnecting to spirit

The sacred responsibility of this way of worldbuilding, the connection to lineage and ancestral memory–bringing the wisdom of what was into what will become–is spirit work. It is work that requires tending to sustain it, but also sustains us. We seek spirit the same way sunflowers seek the sun.

We seek connection to spirit not just to ask for what we want, but to remind us of our humanity, our power, and our clarity in service to a higher purpose–a world where all beings can thrive. And that world is taking shape each day, in the relationships between us. If we are the candles that cannot be extinguished, our connection to spirit and purpose kindles the flame so that we can light other candles.

Claiming power

The flames we tend are a reminder of our power. The power that naturally comes from connection to source and purpose. The organic current of creative energy that flows when we’re in alignment with purpose and care. Despite the ways oppressive systems try to diminish our power, we are transforming ourselves, our communities, and our collective systems.

We claim our power when we see ourselves within the system–when we see and feel the way our agency, our choices can be used to change it. When our individual agency and power becomes collective. We claim our power when we refuse to be separate–from ourselves, from each other, and from the generations that came before and will come after us. When we accept the sacred responsibility of choosing the way we want to be, in alignment with the world we want to live in.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Weaving at Work

September 20, 2022Network mapping,Network Weaving,TransformationBlog,Systems Change,Weaving,Collaboration,workplace

Over the past few years, I have been increasingly influenced by the concept of “weaving” — what for me means connecting people, ideas, and projects to foster more collaborative social change.

Weaving is a skill, a mindset, and a way of being. More art than science, it requires deep listening, being responsive to interests and needs, and “sensing” opportunities to bring people or projects together.

In many ways, it’s synonymous with other terms we use like facilitation, collaboration, networking, community building, relational leadership, etc.

I find weaving to be an incredibly powerful tool for fostering collaboration, decentralizing ownership, and sparking wide-scale impact.

But weaving often clashes with our traditional workplace habits and structures

One of the things I’ve been struggling with lately is how to make weaving a regular and consistent part of our team.

In the network I run, despite multiple attempts weaving still doesn’t show up in our to-do’s or our impact tracking system. When our time is limited (which is almost always), it quickly becomes a “nice to have”.

Often, we work in systems that are linear, logical, and task-based—from project management, to communication and coordination, to data analysis. Weaving is by nature more intuitive, emergent, and relationship-focused, and sometimes just doesn’t seem to fit.

As a result, weaving can be hard to integrate into our task lists, to coordinate across our team members, and to openly report on. And because our managers and supporters usually don’t see or experience it themselves, it can go unnoticed and misunderstood.

So how can weaving become a core activity that we regularly practice and valorize in our workplaces?

Last week, June Holley and I hosted a brainstorming session with the Weaving Lab around this question. Here are some of the ideas that came up:

- Weave everywhere, all the time — and explicitly state that you’re doing it. For example, in interviews you can cluster small groups of people who don’t know each other and tell them relationship building is a core goal of the interview. In team meetings you can leave time for storytelling and explain why this is important for building trust. In large group events you can integrate simple getting-to-know-you activities, and explain how connections are the core of any collaborative work.

- Explicitly write weaving in our daily task lists. Be they digital or analogue, try to make sure weaving is written down as a regularly-occurring task (e.g. weekly) for each team member. So even when a direct opportunity for weaving doesn’t show up to you, your job is to “find” one.

- Enable weaving through a light-touch database system. Keep an updated list of your team and community members’ needs, interests, gifts, skills, fields of work, engagement level, etc. Make it simple, so it’s easy to skim. And use your weekly task to actively “identify” new opportunities for weaving (don’t expect community members to do this themselves!). For example: find 3 people who haven’t met but you think would get along and introduce them to each other. Or, share a funding opportunity with 4 people working in a similar field of interest. By the way, CRM systems aren’t set up for this, so consider using a flexible tool like Asana or AirTable, or a network mapping tool like Kumu.

- Don’t weave alone or in isolation — weave with others. Mark “weaving opportunities” as a fixed item in your team meeting agenda. This helps you better coordinate to avoid overlap, be creative in finding weaving opportunities, and be accountable to making it happen, while also building a culture of weaving. One note:make sure your team has diverse weaving capacities so you can complement each other.

- Document and share weaving through simple and regular processes. Integrating weaving updates into your team meetings—e.g. “what relationships have we build this week” — so you capture and share things you may not have recalled. Have a simple “checklist” for immediately logging when weaving occurs (make it super easy, 15–30 seconds to open, log, and close). And do annual surveys and check-ins with your community to see what impact weaving has had over time.

- Help people whose support you need (e.g. bosses, funders) to “get” it. Use common concepts and metaphors that can make weaving easier to understand. Collect stories of weaving and share those with them. Invite them to to engage directly in weaving practices (e.g. a peer-to-peer problem-solving session where they can get support on a challenge they face and experience weaving in practice). And hold multiple meetings with them where you let them can ask you questions and get to know the practice better.

What would you add?

Brendon Johnson is a seasoned changemaker with a passion for strategies and models around networks, communities, participatory organizing, and collaborative action

Originally published at Medium

Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here