MEASURING LOVE in the JOURNEY for JUSTICE

Below is the preface to this week's featured resource: Measuring Love in the Journey for Justice. Find the link to download this Brown paper at the end of this post.

MEASURING LOVE

Preface: A Sovereign Perspective

As this is a Brown—not white—Paper, we want to give some perspectives before you dig in. In a sovereign, self-determining perspective, we see Two Spirit people as sacred gifts. Children are treasured. Elders are respected and privileged. Womyn are beloved and respected and have power and voice. Fathers, sons, and boys are lifted up as the warriors, believers, and loyal friends that they are. Mothers, daughters, and girls are as valued as life itself, seen and treated as blessings. And all relations are sacred.

To be sovereign and free, our people need policies made of love, forgiveness, and connections.

As oppressed, exploited people of color in this work of social and racial justice, we have seen — and are seeing—children separated from their caregivers, caged in concentration camps. We are living in another era of the systemic denial of democratic civil rights. To be sovereign and free, our people need policies made of love, forgiveness, and connections. Our communities deserve health and educational equity; land and housing justice; economic independence; living wages (as in universal minimum income). Our people want restorative justice practices to replace punishment and lockup. Our communities want community organizing and advocacy, block by block. Our people need community controlled governance and accountability systems. We want civic leadership everywhere, as the right to vote goes with the rights to drive, assemble, drink, and travel.

This Brown Paper flips the script of what is acceptable as a “Paper” on its head. It is not a “formal,” research-based, finished product of the traditional type. It comes from the heart and is meant to be used—like love. It is meant to spark dialogue and provoke.

In it, we are asking ourselves, “Are we loving bravely enough?”

And “How much am I loving?” “What else I can do to be in community from a place of love?” and “How am I wielding power fused with love?”

These are the essential questions posed in our brown paper. We are excited to bring this out into the world to provoke, connect, and build with you.

We have so much to love. We love YOU because we know if you’re reading this paper, you know what it’s like to be powerless and not feel loved—and are working on bringing about more justice in the world.

We release our intentions into the universe. We want to know what your reactions are. We thank you for honoring us by your comments and discussion.

Spread your love. And, we know we are rising as one.

Download Measuring Love in the Journey for Justice HERE

Shiree Teng has worked in the social sector for 40+ years as a social and racial justice champion – as a front line organizer, network facilitator, capacity builder, grantmaker, and evaluator and learning partner. Shiree brings to her work a lifelong commitment to social change and a belief in the potential of groups of people coming together to create powerful solutions to entrenched social issues.

*After the Measuring Love Brown paper was released, Shiree's co-author was arrested on allegations of child molestation. She addresses this in a "Letter to Beloveds" - an excerpt from her next collaborative paper, Healing Love into Balance. (which will be highlighted at NW in the coming weeks.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

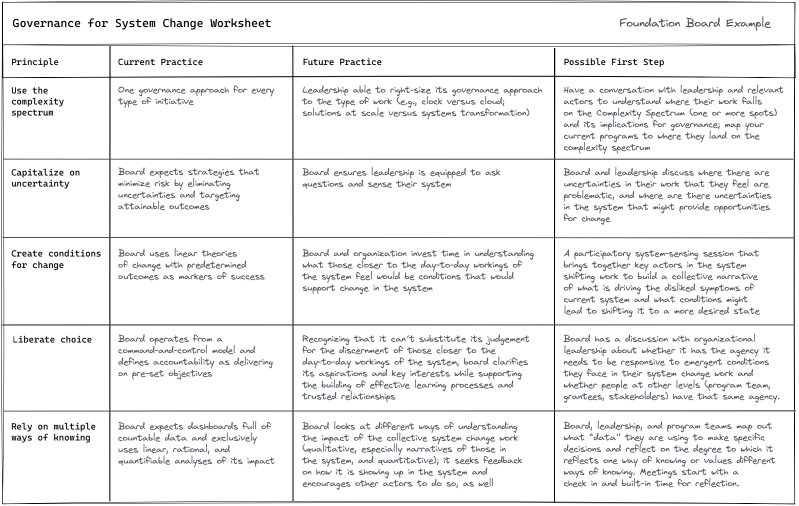

Governance for System Change

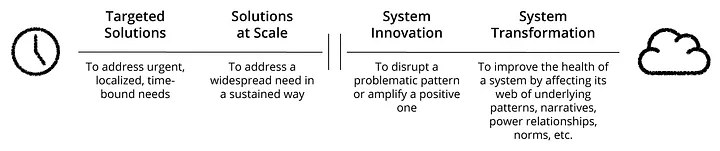

The Complexity Spectrum blog describes how clock and cloud (non-system change and system change) approaches require fundamentally different strategies and tactics. The same goes for the mental models and processes we use to govern system change work.

In fact, governance for system change may not look much like traditional governance at all. Webster’s defines governance as “overseeing the control or direction of something.” Because system change work is emergent, long term and comprised of dispersed and diverse actors, centralized control and oversight is unworkable if not impossible.

Rather, system change work requires distributed decision making in pursuit of a common aspiration and in response to emergent facts on the ground. While centralized control may be impossible, there are ways to bring coherence to this work, increasing the probability of shifting a system to a more desired state.

In this case, governance applies to anyone who makes important decisions that affect the probability of success of a collective system change endeavor, and not just to members of a board of directors.[1] This type of governance is difficult and often requires building a range of new practices over time. Here are a few practices that may help:

- Capitalize on uncertainty to lower risk and increase chances for success.

- Focus on creating the conditions for change over short-term outcomes.

- Liberate choice rather than trying to control it.

- Rely on multiple ways of knowing as you navigate the journey.

Practice #1: Capitalize on Uncertainty

“Uncertainty is an uncomfortable position. But certainty is an absurd one.” -Voltaire

Depending on where you engage on the Complexity Spectrum, uncertainty can be a problem or it can provide a valuable opportunity.

Targeted solutions require a technical approach where you move efficiently along a mostly known pathway from a known problem to a known solution. Take for example a population that has been displaced by a natural disaster. We have experience dealing with this type of situation (known problem) and delivering the targeted solution of emergency shelter (known solution) though various tried and true means (mostly known pathway). In this case, uncertainty can be disruptive because it creates barriers between the problem and the solution.

Solutions at scale usually require an adaptive approach (think Human-Centered Design).

For example, in California many more people were eligible for benefits to alleviate poverty and food insecurity than were applying for them. The reasons why the problem existed were fairly well understood (sufficiently defined problem). In response, Code for America talked to people to understand why they weren’t applying and how they could provide a solution. They built an app, iterated it, and eventually launched a product (GetCalFresh) that greatly increased the number of eligible people applying for benefits (iterated to find a solution that was initially unknown).

An adaptive approach requires a fair level of certainty about the definition of the problem and its causes — enough to support a process of managed uncertainty in which you experiment to find deeper causes and solutions to the problem.

System transformation calls for an emergent approach.[2] In an emergent approach, while you are likely certain about the negative symptoms of the challenge (e.g., high levels of poverty or inequality), the deeper drivers of the problem and reasons for its persistence are mostly unknown or misunderstood. Consequently, the ways to address these drivers are also mostly unknown (or unformed). The key is to nurture the conditions that will support the system healing itself (e.g., understanding the systemic drivers of the challenge and supporting the emergence of ways to address them).

In an emergent approach, uncertainty unlocks opportunity. When complex challenges persist over time despite efforts to address them, there is often a sense of frustration, even despair. However, this can lead to the realization that we don’t have all the answers, which can make us more open to thinking differently.

Some forms of systemic analysis, like dynamic system mapping or participatory futures, provide a structured process for thinking in new ways about an all-too-familiar problem. When doing participatory system mapping, aha moments often arise when participants identify a pattern that explains why change has been elusive. It is empowering to see an old problem from a different perspective and find a possible path forward.

Effective system sensing should lead to confidence that you have “good uncertainty” — or trust that there are good questions to explore and a way to experiment and learn more about the system and how to engage it. Think of uncertainty as a gateway to doing things differently and finding ways to unstick a stuck system.

Practice #2: Focus on Creating the Conditions for Change

Uncertainty is uncomfortable because it increases our fear of failure. It makes us anxious. One common but ultimately unhelpful response is to over-rely on short-term substantive outcomes that are a small piece of the ultimate outcome we want to see. [3] For example, if we are looking to end human slavery in global supply chains, we might measure progress by looking for annual percentage reductions in the estimates of slave labor by 5% or so each year.

It is wise to understand the impacts our work is having in the short term, if for no other reason than to detect and mitigate potential negative impacts. However, there is a danger of using pre-defined, substantive outcomes as waypoints to navigate our way on the journey toward long-term system change.

Specifically, there are two key dangers:

- Short-term outcomes dominate our time, attention, and resources and reduce commitment to long-term change. According to neuroscientist Ian Robertson, “success and failure shapes us more powerfully than genetics and drugs.” This means short-term successes can lead people to invest more time, resources, and emotional commitment in concrete short-term outcomes instead of longer-term, hazier systemic shifts. Moreover, grantees often need to trade annual impacts for continued funding, so pre-identified short-term outcomes take priority.

- Short-term impacts can be bad predictors of long-term, systemic impact. In complex systems, impact is not static. What may seem like a good outcome in the near term, might drive negative downstream impacts in the months and years ahead. Basing future investments mostly on short-term outcomes can lead to bad long-term investments.

The implication is an inexorable pull away from making the hard choices and risk tolerance needed for system change. As a result, the pursuit of specific substantive outcomes in the short term may make it more likely a system change effort fails in the long term.

Fortunately there is an alternative. Alice Evans, who in her time at Lankelly Chase helped build their systems practice, said a key enabler of their work was the realization that creating the conditions for system change should be their focus rather than targeting specific outcomes those conditions might produce.

For example, there are a few generic conditions that will apply, in some form, to most system change initiatives. These include the degree to which important system actors can:

- See their context as a complex system and use that shared understanding to inform action and increase the potential coherence of distributed action.

- Identify and engage patterns that people believe will unlock change (e.g., weakening patterns that sustain the problem or strengthen bright spots that can shift the system).

- Build or strengthen connections, networks, and information flows across the system.

- Build an infrastructure for learning and, as Marilyn Darling says, “return that learning to the system.”

Elaborating these and other conditions that might support system change requires a participatory process that prioritizes the voices of those closest to the day-to-day operations of the system.

As we look at the conditions we are trying to cultivate, we must also look at those in ourselves and in our organizations. We are all part of the respective systems we are engaging and it’s critical to contend with power and who is making decisions both within an organization and in a broader system impacted by those decisions. If you haven’t already done work on your own relationship to power and how it impacts your work, now might be a great time to dig in. Consider asking:

- How are we showing up in the system? What feedback are we getting about how we’re showing up? Are we working in a system-informed way? How do others experience our presence?

- What is the quality of our relationships with other key system actors? How have we prioritized the voices of those closest to the context?

- How do we understand our own power in the context we are working in and the people we are working with? How do others perceive it? How can we engage others in an honest conversation about our relative power?

Fortunately, changing how we show up in a system shifting initiative is a condition over which we have the greatest control. Unfortunately, many of us, especially funders, show up in ways that replicate or entrench unhelpful power dynamics that constrain choice and make distributed decision making impossible. This means a critical early condition for system change is understanding and adapting the ways in which our organizations — and even ourselves — work. For more thoughts on internal organizational conditions and how to work toward them, see Building Emergent Organizations.

Practice #3: Liberate Choice

Successful system change requires those closest to the day-to-day operations of the system to be highly adaptive over time in response to emerging realities.[4] However, this is hard to do with traditional governance processes that seek to maximize control and minimize risk.

For example, a standard grant agreement trades funds for outcomes identified by the donor, which replicates the power dynamic of “those with resources call the tune.” This dynamic too often prioritizes donor interests rather than those most impacted by the funding, removes agency from those closest to the context, and creates highly transactional relationships.

If funders behave in ways that reduce the agency of these actors, they inhibit their ability to work for system change.

The alternative to donors limiting choice is to use what Cyndi Suarez calls “liberatory power,” or the ability to “create what we want” by transforming “what one currently perceives as a limitation.”[5] A key question for donors wishing to support system change is, how can we increase the ability of key actors in the system to effectively connect with each other, sense, sense-make, act on, and learn from their system?

Each level of actor in a system change initiative can liberate the choices of actors in the system. Liberating choice is not the same as giving more choices — it requires both the presence of choice and the agency to act on it. A board of directors needs to liberate choice for organizations they oversee; leadership of an organization needs to liberate choice of its program teams; program teams need to liberate choice of grantees and partners; grantees and partners need to liberate choice of stakeholders and community actors; and based on how information flows in the system, stakeholders can liberate choice for program teams, etc.

This is not the same as simply giving money and getting out of the way. Liberating choice does not mean removing all structure. Many argue there is no such thing as structurelessness when it comes to any kind of group activity, especially when one actor is providing significant resources to support the work of other actors.[6] Donors need to provide enough structure to enable choice, but not so much as to prematurely curtail choice.

The key is to create minimally sufficient, helpful structure. For donors supporting system change, there are some key components to creating minimal structure, which include:

- Articulate a common aspiration or guiding star.[7]

- Clarify boundaries by articulating key interests and values.

- Establish an infrastructure for learning.

- Invest time in building trusting relationships among system actors.

Of these four points, clarifying boundaries or guardrails may be the most difficult. An unhelpful but familiar way of doing so is to provide directives to either do or not do something. A more useful approach is the “even-over statement” as developed by Tom Thomison and popularized by Aaron Dignan.

The benefit of even-over statements is that they share how different actors in the system might make tradeoffs between key interests and values. The statement consists of two “good things” and says, “if confronted with a choice, I would choose this good thing over that good thing.” However, it aims to preserve the agency of an actor to make a decision in light of the specific situations that they find themselves in.

Some generic even-over statements that liberate choice for system change include:

- Prioritize responsible, smaller experiments even over concentrating resources on large-scale bets.

- Invest time in building trusting relationships even over delivering on preset timelines.

- Value responsible learning even over clear-cut wins.

- Foster regular, honest feedback across the network of actors even over preserving harmonious relations.

Whatever boundaries you try to set, and however you set them, they will be wrong in some respect. This is where a dynamic learning process is essential. Part of that learning process needs to ask to what degree are the boundaries and common aspiration helpful? In what ways are they affecting people’s thinking and behavior? Are they strengthening agency of system actors or reducing it? What might we do better?

And none of this works if the relationships between actors in a system change initiative are mainly transactional. Because system change work is highly emergent, it requires real time and honest communication and the ability to work in a decentralized way. All of this requires high levels of trust between actors, and this level of trust does not happen unless they invest time in it. This can be particularly difficult for funders who see investing time to build trust as simply increasing overhead.

Practice #4: Rely on Multiple Ways of Knowing

“There is a strong bias in the U.S. dominant culture, one that shows up in the nonprofit sector as well, to value only one way of knowing, the one grounded in data, analysis, logic, and theory — a rationalist’s approach to truth.” -Elissa Sloane Perry and Aja Couchois [8]

Working effectively in complex systems requires strengthening our ability to use multiple ways of knowing. It is essential for implementing the practices described above. Unfortunately, as the quote from Elissa Sloane Perry and Aja Couchois indicates, the default capacity for many in the West is to privilege only one way of knowing — a cognitive, analytic approach.

This is not to say we should devalue rational analysis. Rather, it means putting a high value on the ways others understand their world and make decisions about how to act.

There are various ways to define multiple ways of knowing, from Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences to the model of five minds described by Tyson Yunkaporta.[9] A simple way to look at multiple ways of knowing is: thinking, feeling, and intuiting.[10] At a minimum, it means asking: what do you think about the situation, how does it make you feel, and what is your gut telling you to do? It means listening to how others think, feel, and intuit.

Listening to feelings and intuitions is not the same as following them. Rather, it means understanding how information, situations, and decisions make us and others feel; allowing our intuitions to come to the surface; and not automatically subjugating these to what we might judge as rational or rigorous analysis. It means sitting with differences and uncertainty and valuing the important stories people tell about their system, and not just the numbers they can fit on a spreadsheet.

For many, this is the most disruptive practice for system change governance. It requires us to change how we think about and develop strategy, how we evaluate our effectiveness and that of our grantees, and how we make decisions. It means that good questions are often more useful than seemingly good answers. Fundamentally, it changes how we know what we know (e.g., how we weigh a quantitative analysis versus the lived experiences of partners on the ground).

But as disruptive as it can be, cultivating multiple ways of knowing is worth it. There are several reasons why: from the neuroscience that shows the role of emotions in decision making to the necessity of multiple ways of knowing for advancing equity.

In addition, there are simple, practical arguments for cultivating multiple ways of knowing from a system change perspective:

- If shifting systems involves diverse actors spread across geographies and cultures, different ways of knowing will always exist in the network. This means effective system change work requires the ability to understand and work with those different ways of knowing.

- And, because complex systems are murky and constantly changing, it is naïve to rely on only one way of knowing. Each way of knowing has limits but, together, multiple ways of knowing increase our effectiveness.

- Lastly, multiple ways of knowing are essential because we can’t just reason our way to system change — rather it requires a dynamic connection between head, heart, and gut.

One accessible way to start bringing multiple ways of knowing into your work is to play with meeting structure. Try starting meetings with a check-in question like “how are thinking and feeling coming into the meeting?” Or you could ask something more playful like “what was your favorite movie character as a kid?” A more serious question could be “can you describe a time when you felt truly happy?” Think of it less as an icebreaker and more of a space for people to welcome in their whole selves and deepen relationships. It also helps to build in time for silent reflection in the room, have people journal, or to pair up and process the meeting while taking a walk.

Many people have built more in-depth ways to incorporate multiple ways of knowing. A few I suggest are: the Equitable Evaluation Initiative, for using multiple ways of knowing to build more equitable evaluation processes; Relational Systems Thinking: That’s How Change Is Going to Come, from Our Earth Mother by Melanie Goodchild, for how to realize the benefit of differing world views and ways of knowing; and Theory U by Otto Scharmer, for a comprehensive approach to system change that has multiple ways of knowing at its core.

Next Steps

Learning to use a different frame for how we govern system change is a practice, and it takes time to develop. Devoting time to consciously changing your governance practices is the first challenge you will confront. But remember, systems seldom change on a dime, and neither do we. You might want to start with the system you know best and are closest to — you and your own organization.

One way to start is to use these governance practices as a set of prompts for your own self-reflection and experimentation, such as:

Using the Complexity Spectrum. How are we differentiating among our organization’s approaches along the Complexity Spectrum? Are we developing different mindsets and practices for clock versus cloud initiatives (e.g., solutions at scale versus system innovation or transformation)?

Capitalize on uncertainty. How are we cultivating good uncertainty and capitalizing on it? Are we resisting the urge to create certainty when there is none?

Liberate choice rather than trying to control it. Do those closer to the context feel they are able to make the choices needed to engage the system effectively? How well are our aspirations, guardrails, and learning processes helping us learn from the choices we make? What levels of trust are we able to build?

Focus on creating the conditions for change. What are the conditions that will support change in our organizational system? How well are we supporting them? How might we revise them? How are we understanding what others in the system feel are the conditions that will drive change?

Rely on multiple ways of knowing as you navigate the journey. Are we getting in touch with our own ways of knowing and cultivating openness to others? Are we trying both small and large experiments? (e.g., creating space in meetings for check-ins and reflection time? Building a more equitable evaluation practice or sitting in the tensions between different world views?)

Lastly, give yourself and those around you room and permission to change. Rather than expecting to get it right, focus on getting it better. Together I think we can do just that.

Download a PDF of the blank worksheet

Download a PDF of the example worksheet

Acknowledgement: While I take responsibility for the words used in this blog, the ideas come from dozens of colleagues, hundreds of conversations, and thousands of hours of experimenting and learning by many.

[1] I will often refer to the work of a foundation board because this is the context I know well.

[2] I am using the terms technical, adaptive, or emergent approach instead of technical, adaptive, or emergent strategy to avoid confusion with established writing on these types of strategy. There is a fair amount of commonality of usage of the terms technical, adaptive, and emergent between this piece and earlier works, but there is not 100% overlap and I want to avoid confusion or to imply that I am redefining these types of strategy. For writing on the subject, see the works of Ron Heifetz, Adrienne Marie Brown, and Henry Mintzberg.

[3] In this case, substantive outcomes mean measurable changes to the symptoms of the problem we are concerned with, as opposed to the process by which we work.

[4] This is particularly important when working with complex systems where those closest to the context need the ability to respond to what they are learning. This is what Gen. Stanley McChrystal found in doing counterinsurgency work and wrote about in his book, Team of Teams. McChrystal saw the need to empower choice from units on the ground by creating more distributed decision making.

[5] See The Power Manual by Cyndi Suarez, p. 13.

[6] See The Tyranny of Structurelessness by Jo Freeman who wrote about organizing the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s. Here is a relevant passage: “Contrary to what we would like to believe, there is no such thing as a structureless group. Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power, and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved.”

[7] For guidance on developing a guiding star, see the Systems Practice Workbook.

[8] Multiple Ways of Knowing: Expanding How We Know, April 27, 2017, Non-Profit Quarterly.

[9] Here is a quick description of the five minds.

[10] Here a quick explanation of the science of intuition: “Intuition is a form of knowledge that appears in consciousness without obvious deliberation. It is not magical but rather a faculty in which hunches are generated by the unconscious mind rapidly sifting through past experience and cumulative knowledge.”

Rob Ricigliano is the Systems & Complexity coach at The Omidyar Group, where he supports teams as they engage complex systems to make societal change.

originally publshed at In Too Deep

featured image by kazuend on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

Ceremony: Reyoking the Sacred with Our Social Justice Work

“Disability is an invitation to relationship…It’s that opening that creates the whole ecosystem.”

– Sophie Strand

“Poetry is the language of the apocalypse.”

– Bayo Akomolafe1

As the newest members of turtle island, two-leggeds have always relied on ceremony for connection with, and for instruction from, older forms of sentience and the divine. Ceremonies are an essential part of all cultures across time. It is the absence of such sacred practices that results in disharmony, imbalance, and collective dis-ease. But what ceremonies and by and for whom? As social justice practitioners who come from a broad range of communities, cultures, and traditions, we often have few, if any, shared approaches for bringing together people, place, and spirit. This challenge has only been compounded during the pandemic, which has shifted so much of our work to a video screen.

While there are a number of rituals—often used by social justice practitioners—to help people connect across the virtual landscape, these tend to have more intellectual and emotional dimensions than spiritual. The increasing attention to somatic practices is expanding how we engage with one another in healthy and embodied ways, but our connection to the sacred, to sentience in its myriad of forms, to place—whether it be turtle island as a whole or a particular place on the carapace of her shell—is largely absent in our cross-cultural social change work. And it is this absence of ceremony that is impeding our ability to radically transform, as people and as a complex and interdependent ecosystem as a whole.

Members of the Change Elemental team and many others have written about the importance of inner work, of attending to the interiority of the intervener. But this work is often done separately, as individuals, or in our own spiritual communities, and not centered as much in our collective change efforts. There are exceptions of course, but these only make more stark the general absence of collective practices.

What is needed, what has always been needed, for transformational change, is ceremony—ceremonies in which we reconnect deeply with each other, with great spirit, with all of creation. In God is Red, Vine Deloria, Jr. describes the importance of ceremony for Native peoples. “The task of the tribal religion, if such a religion could be said to have a task, is to determine the proper relationship that the people of the tribe must have with other living things…” As all of creation is sentient—lizards, rocks, trees—then proper relationship is necessary with everything. And how that relationship is learned, celebrated, and restored, is through ceremony.

The healing of injustices and the restoration of aki, of the earth—including all of the creatures who depend on her and on whom she depends—requires restoring indigeneity—that is a deep connection to place, to its sacredness and interdependencies, to cultural sensibilities that are shaped by these.2 This is an individual, collective, and planetary necessity. The restoration of indigeneity requires reconnecting to indigenous practices, whether those practices are indigenous to the Americas, Africa, Asia, or Europe. For those who are not connected or actively reconnecting, this then is your task—and yes, it can be complicated, painful, and messy. It is an extension of inner work, of cultivating the ability to be present to what is and was and then draw on this ability to help create what will be.

And too, when we come together as change makers, we must hybridize and invent new ceremonies to support our current collection of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic beings—all while centering the primacy of the indigenous world in which we are currently walking. It is a potent task, but not without antecedents.

The evolution, resistance, and resilience of indigenous spirituality in the face of settler colonialism and the middle passage provide some clues for how we might accomplish such transgressive divination. And while these adaptations were the result of subjugation and duress, our current times—the extraordinary amount of injustices we are quite literally buried in—necessitate another sacred leap in order for us to work collectively together.

So, how do a diverse group of social justice practitioners develop and practice ceremonies together? One answer can be found in Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer:

I knew that in the long-ago times our people raised their thanks in morning songs, in prayer, and the offering of sacred tobacco. But at that time in our family history, we didn’t have sacred tobacco and we didn’t know the songs—they’d been taken away from my grandfather at the doors of the boarding school. But history moves in a circle and here we were, the next generation, back to the loon-filled lakes of our ancestors, back to canoes…. When I first heard in Oklahoma the sending of thanks to the four directions at the sunrise lodge—the offering in the old language of the sacred tobacco…the language was different but the heart was the same…. It was in the presence of the ancient ceremonies that I understood that our coffee offering was not secondhand, it was ours…. That, I think, is the power of ceremony: it marries the mundane with the sacred. The water turns to wine, the coffee to a prayer. The material and the spiritual mingle like grounds mingled with humus, transformed like steam rising from a mug into the morning mist.3

We find ceremony and we create it together. The languages may be different but the heart is the same. And in that collective mingling, we weave relationships with ourselves and each other, with spirit, and with all other sentient beings.

Learning the grammar of animacy [and here this means recognizing the sentience and aliveness of “things”] … reminds us of the capacity of others as teachers, as holders of knowledge, and as guides. Imagine walking through a richly inhabited world of Birch people, Bear people, Rock people, beings we think of and therefore speak of as persons worthy of our respect, of inclusion in a peopled world….imagine the possibilities. Imagine the access we would have to different perspectives, the things we might see through other eyes, and the wisdom that surrounds us. We don’t have to figure out everything by ourselves: there are intelligences other than our own, and teachers all around us.4

We are living in places flush with sentience. Whether we are working together in person and are able to root into the same soil and arc into the same sky, or we are connecting virtually from across the continent, we can be present to place, to plant and animal teachers, to the places and wisdom of our ancestors, as well as to the divine. In either circumstance, what matters is this presencing of sacred relationship, that we make our interconnectivity the space from which we do our social justice work. Not for reasons of emotional stability or creativity—although it does support both—because the problems we are trying to solve cannot be solved by human beings alone. Both Albert Einstein and Audre Lorde have told us this in different words. Einstein informed us that, “you cannot solve a problem with the same mind that created it.” And Lorde located this understanding alongside its concomitant history when she wrote, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Human beings do not, in isolation, have the ability to solve the problems we have created. A recent example of this can be seen by the effect a simple virus—one of the oldest life forms on the planet—has had on every nation across the globe. The response to this virus has been utterly human-centric, and in the US, utterly middle-class, housed, professionalized worker, and male-centric. And it has been to the peril of every social system, which by their design for and maintenance of inequities then resulted in cataclysmic harm to Black, indigenous, brown, immigrant, female-identified, disabled, refugee, poor—the list is endless—communities across the world. All of creation, whether we look to the big bang or to sky woman falling5, teaches us that we are wildly connected and interdependent, and without our devoted attention to this truth, we will, and do, continue to find ourselves tilting precariously over the edge of a cliff.

The way we presence this connection, the way we center its fundamental truth, is through ceremony. Ceremonies born of our disabilities, our differently-abled abilities, which, as Sophie Strand says, create the opening that enables an entire ecosystem to unfold. This opening too is ceremony. Ceremony is the poetry that languages a new way of being and ways of doing such that the apocalypse can utter its death rattle, be composted, and make way for the regenerative growth of the post-apocalyptic, indigenized, recombinant world in which all of creation can face one another, bow, and begin the dance anew.

1Quotes from their shared talk “New Gods at the End of the World” hosted by Science and Nonduality (SAND)

2“Indigeneity assumes a spiritual interconnectedness between all creations, their right to exist and the value of their contributions to the larger whole.” LaDonna Harris, Founder and President of Americans for Indian Opportunity

3Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants.” Milkweed Editions. Minneapolis, MN. 2013. Pg. 36-38

4 Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants.” Milkweed Editions. Minneapolis, MN. 2013. Pg. 58.

5 There are many written versions of this creation story. One of my favorites is `“You’ll Never Believe What Happened” is Always a Great Way to Start’ by Thomas King from his collection The Truth About Stories, House of Anansi Press, Inc. Toronto, Ontario. 2003.

Aja Couchois Duncan (she/her/we) is a San Francisco Bay Area-based leadership coach, organizational capacity builder, and learning and strategy consultant of Ojibwe, French, and Scottish descent. A Senior Consultant with Change Elemental, Aja has worked for 20 years in the areas of leadership, equity, and learning.

Header image credit: Taylor Wright

Originally published at Change Elemental

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

The Complexity Spectrum

Systems change is not for everyone, but making a good choice is

Philanthropies are increasingly becoming key players in the field of systems change. As organizations grow more innovative and risk tolerant, they are logical partners to those working to shift systems for the better.

In addition, the work many philanthropies are doing to reckon with drivers of inequities and racism — which very often contribute to their accumulation of wealth — requires many of the same changes that systems work calls for. In fact, breaking the deeper patterns that drive racism is itself a system change effort.¹

Systems change, however, requires philanthropies to operate in ways that are often unfamiliar, even counter to traditional ways of working. While we all need to see the world through a complex systems lens, systems change is not an approach that every philanthropy can responsibly pursue.

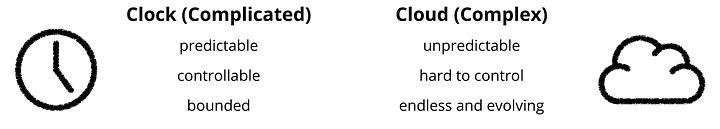

Clock vs. Cloud

Systems change is a “cloud problem” that exists in a world built for “clock solutions.”

The clock vs. cloud (or complicated vs. complex) distinction is based on the insight that most challenges lean toward two distinct types:²

These two types of problems require two fundamentally different approaches:

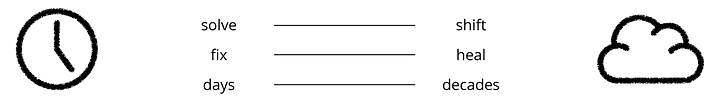

Like most organizations, philanthropies traditionally focus on a clock approach: solve problems, fix what’s broken, and get it done as quickly as we can. But that’s not how systems work:

- Systems don’t get solved. At best, we hope to shift systems to a healthier state.

- Systems don’t just need things fixed. They need healing — healing of relationships, historic inequities, destructive patterns, and the environment.

- Systems are infinite. There is no finish line that can be crossed in days or even a few years. Maintaining healthy systems is an ongoing task.

Damage can be done when we try to fix what needs to be healed or think we can solve that which is unsolvable. Rather we must apply the appropriate approach to the type of problem being addressed.

“We shouldn’t try to fix what needs healing or heal that which can be fixed.

- Dr. Failautusi (Tusi) Avegalio, University of Hawaii

Philanthropies interested in pursuing system change should avoid thinking of mission in terms of solving problems — or worse, thinking they can fix in a matter of months or even a few years that which needs healing. In contrast to a mission statement that is some form of “we exist to solve the world’s biggest problems,” systems change needs a different formulation. Something like:

As a philanthropy, we make good use of our resources to support the well-being of people, relationships, processes, and ecosystems as they grapple with complex and dynamic challenges.

Why “good use” instead of “highest and best use?”

Philanthropies often think being good stewards of their resources means putting those resources to their highest and best use. But highest and best is an impossible standard when dealing with the uncertainty and unpredictability of cloud problems. Moreover, highest and best implies an expectation of perfectionism which, while a conceivable aspiration in the clock world, can be counterproductive, even destructive in the cloud world.³

Why “support the well-being” instead of “solve problems” or “create impact?”

As outsiders, as opposed to those living in the system, a system is not our problem to solve. In cloud environments, change often takes time and has multiple influences and repercussions. Tying something you did to a specific, sustainable, and systemic impact is nearly impossible.

Why “people, relationships, processes, and eco-systems?”

These are the sources from which system change emerges. It takes a system to change a system. Lasting change is more likely to happen if those in the system, as well as their relationships with each other and with the wider environment, are healthier.

A Spectrum of Choices

The goal in exploring systems change for philanthropies is not to argue that everyone should be doing this type of work. The goal is to help philanthropies make good choices about how to use their resources (financial, people, social, network, etc.)

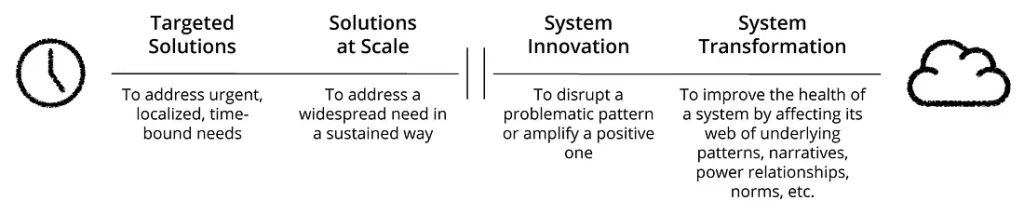

The choice of systems change is not a binary one. Rather there are distinct types of problems and interventions that exist along the spectrum from clock to cloud.

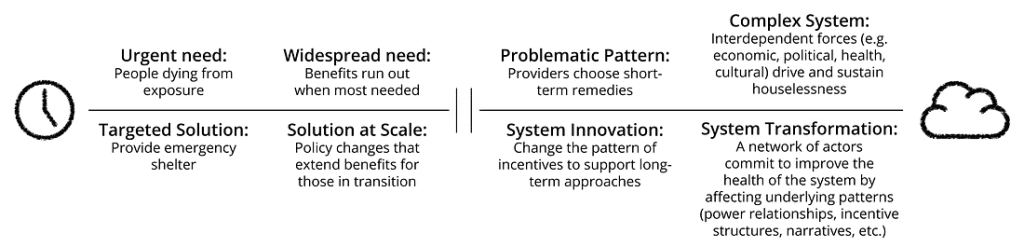

To illustrate the Complexity Spectrum, take the issue of houselessness:

The key to understanding the Complexity Spectrum is understanding differences in clock and cloud problems and approaches. The defining characteristic of a cloud approach is that it targets the underlying patterns of behavior that make up a system and drive the outcomes the system produces (e.g. underlying patterns that drive levels of poverty and make it difficult to “fix” the impacts of poverty like lower life expectancy, increased stress levels, etc.) If an approach aims to just lessen the extent of a problem or ameliorate the impacts of it, it’s more clock than cloud.

The murkiest part of the spectrum is the difference between Solution at Scale and System Innovation. This can be confusing because the same tactic can be a Solution at Scale or a System Innovation depending on how it is implemented. Take for example Housing First in Salt Lake City and Calhoun County, MI.

In Salt Lake City, Housing First was used to remedy the problem of the chronically houseless, defined as houseless people with histories of substance abuse or mental illness. As a Solution at Scale, it was effective. Chronic houselessness was cut by 90% for the target population over a ten-year period.⁴

This success was hailed as an example of how Salt Lake City had solved houselessness. But over the same period, the number of people living in houseless shelters doubled. Why? The program was designed to solve a widespread need among a portion of the city’s houseless, but it was not designed to address the many complex and interconnected forces that drive houselessness and make it difficult to emerge from.

In Calhoun County, in a project supported by noted systems change practitioner David Stroh, they asked a different question. What was keeping the network of actors in the houseless system (providers, houseless, government, advocates, community groups) from being more effective at dealing with houselessness? They found these actors were being incentivized by a variety of sources to choose short-term fixes to houselessness rather than work on the more complex reasons driving houselessness in the first place.

The key actors in the system worked collectively to interrupt the pattern of short-term incentives and create a new pattern of relationships and processes by which they would work to deal with houselessness. They too started with the Housing First program, and it was effective. But Housing First was an outcome of a System Innovation approach — it changed key relationships and patterns that drove houselessness in the County.⁵ When the Great Recession of 2008–2009 hit, levels of houselessness did not spike even as there was a major loss of jobs in the area. In this case, a key pattern in the system changed and, as a result, the problem of houselessness was also changed.

Note the type of activity can be the same in a Solution at Scale and System Innovation. The difference is that System Innovation targets a persistent pattern (the incentive structure). The choice of Housing First in Calhoun County was a result of changing that pattern. Conversely, as a Solution at Scale, Housing First in Salt Lake City was used as a direct intervention and did not aim to change the underlying patterns driving houselessness in general. In this case, Housing First succeeded at meeting the needs of a significant population, but it did not change the system itself.

So what’s the main distinction between System Innovation and System Transformation? A system has interconnected patterns that drive the system and its outcomes. A system can have any number of patterns, depending on how deep one wants to go in understanding the system. System Innovation targets one or two of these patterns and its success depends on whether changing a specific pattern is sufficient to create a sustainable, positive change in the overall system. System Transformation, on the other hand, aims at changing the system itself by changing multiple patterns as well as how those patterns affect each other. So the key difference between System Innovation and Systems Transformation is the number and extent of patterns that are being affected.

Making a Good Choice

As the houselessness example portrays, challenges have both clock and cloud dimensions and have the potential for Targeted Solutions, Solutions at Scale, System Innovation, and System Transformation. The point of the spectrum is to show us that, in every situation, we have a choice as to where and how to engage.

Systems change is not right for everyone nor is it necessary for every problem. While the renewed interest in systems change is promising, it has a downside. The popularity of systems change almost certainly means that people and organizations are choosing it when they shouldn’t. They may lack the capacity to do the work, or only do it because they feel it’s what’s expected. Or worse, they may label an initiative as systems change when it isn’t.

Making a good choice is a function of three critical ingredients:

- Your Mission and Values. The expression of who you are, what you care about, and how you want to be in the world

- Your Capacities. Skills, relationships, practices, structures, and mental models at multiple levels (individual, organizational, network)

- Your Context. The ecosystem in which the challenges you care about exist and that affects how they may change into the future (e.g. people, structures, attitudes, narratives, trends, patterns, the natural and built environment, etc.)

Ideally, an organization aims to find the sweet spot where mission and values, context, and capacities align; a particular approach will allow you to effectively serve your mission in a specific context using your distinctive capacities.

Let’s take a hypothetical organization whose mission is to reduce houselessness in a major US city. Assume that organization takes a system-level view of what drives houselessness in their community. As noted above, they are likely to find some version of each of the four challenges (urgent needs to a complex system) and the potential for the four approaches. But assume their analysis also shows:

- The system overall is moving in a positive direction and many novel and promising approaches are emerging.

- Recent policy changes mean there are many new benefits for those in or emerging from houselessness, but there are many obstacles to applying for and receiving those benefits.

- This “benefits gap” creates a widespread need among the houseless.

- There is still uncertainty whether these emerging trends will continue in a positive direction and if policy changes will help, or if old patterns that drive houselessness will re-emerge.

- There are still many houseless who will face urgent needs for shelter when the weather turns cold, and there are many chronically houseless who are still underserved.

The organization is tech savvy, has strong capacity in product development, and solid relationships with local government and houseless providers. They do not have experience in doing systems change explicitly and lack the monitoring and evaluation capacities that highly adaptive system change work requires. And because the organization found solid indicators that the “houseless system” in their community is generally moving in a positive direction, they saw less of a need for the organization to invest in some form of systems change (Innovation or Transformation).

They decide their resources would be best used in pursuit of a Solution at Scale — an app that connects houseless and providers with benefits and simplifies the application process. But they will need to monitor whether urgent needs in the system will grow and make longer-term work much harder, or whether old problematic patterns will re-emerge and potentially undermine even an effective Solution at Scale.

Governing Amidst Complexity

The Complexity Spectrum and the mission-context-capacities framework are designed to help make a hard choice a bit easier — but it is still a difficult one. Of the three variables, capacities pose the biggest challenge:

- Your mission and values are in your control. While they may be ill-defined or out-of-date, you still have control over them.

- Understanding a complex system is difficult, but it is still possible. There are a wide range of systems and complexity tools and practices for sensing systems and how to engage them.

When it comes to capacities, however, I am not aware of any organization pursuing system change that feels they have it all figured out. In fact, I’m certain they never will — because systems are dynamic, as are the capacities needed to engage systems.

Philanthropies, like most organizations, will take time to become agencies of system change. Effective governance — the ability to make a steady stream of decisions in the face of complexity and outside of just the board room — will allow philanthropies to become effective contributors to system change efforts. Governance, in service of being agile and adaptive, is the key capacity that philanthropies must develop to be effective at system change. The next blog in this series will explore this idea further.

* * *

Note on definitions: the use of the term “system” in this piece refers to an aid for learning or discovery — a helpful way to understand reality. In particular, the word system here refers to a complex adaptive system, meaning it is ever evolving and made up of many patterns of behavior that persist and change over time, and which interact with and affect each other. In this sense, system, as used here, is not a real thing; it is a mental model. A complex adaptive system, as used in this piece, is distinct from seeing just the tangible elements of a system (e.g., seeing a healthcare system as consisting of patients, providers, insurers, first responders, nurses, doctors, regulators, etc.) versus seeing the dynamic patterns that drive the level of health in a community (e.g., a poverty trap where people who are poor can’t afford sufficient healthcare; but because their health suffers, their earning potential is limited). The theory behind using the complex adaptive system is that understanding patterns of behavior and affecting them is the way to change such systems over time.

[1] See Systems Change & Deep Equity: An Interview with Sheryl Petty and Mark Leach; And the work of Jara Dean-Coffey and the Equitable Evaluation Initiative; Also Dean-Coffey, J. (2018). “What’s Race Got to Do With It? Equity and Philanthropic Evaluation Practice.” American Journal of Evaluation, 39(4), 527–542.

[2] Clock-Cloud are terms coined in the 1960’s by Karl Popper; Complicated-Complex have been described by Dave Snowden (in the Cynefin Framework) and Brenda Zimmerman.

[3] Okun, T. “white supremacy culture.”

[4] Hobbes, M. “Why Can’t America Solve Homelessness?”

[5] Stroh, D. P. (2009). “Leveraging Grantmaking: Understanding the Dynamics of Complex Social Systems.” The Foundation Review, 1(3). 109–122.

Rob Ricigliano is the Systems & Complexity coach at The Omidyar Group, where he supports teams as they engage complex systems to make societal change.

originally publshed at In Too Deep

featured image by Wolf Zimmermann on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

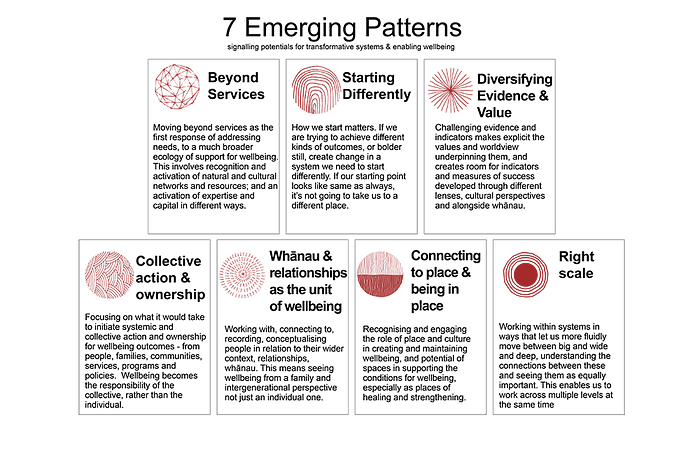

The role and power of re-patterning in systems change

7 everyday patterns to shift systems towards equity

Many recent discussions about civic innovation and systems change have focused on big structural changes that need to take place if we are to grow more equitable outcomes. Along with our friends at TSI / Auckland Co-Design Lab we suspected that we also needed to explore what could happen underneath those structures at the level of more fundamental and ‘everyday’ values, mindsets, behaviours and interactions.

Our combined piece of work began with the hunch that ‘there are already patterns of change that exist and are emerging’. Maybe there were pockets of the future that already exist in the work we were doing that could help transition systems towards equity?

This series on patterns is the culmination of this exploration. We offer it as a demonstration that shifting systems towards equity is possible and that it is the responsibility of everyone to start doing and being differently, in every part of every system, every day.

It introduces seven patterns we have identified across the work of TSI in South and West Auckland that go some way to making visible, active re-patterning for equity and power sharing. This blog and the full PDF introduce the series, and we will release more detail on each pattern over the next couple of months.

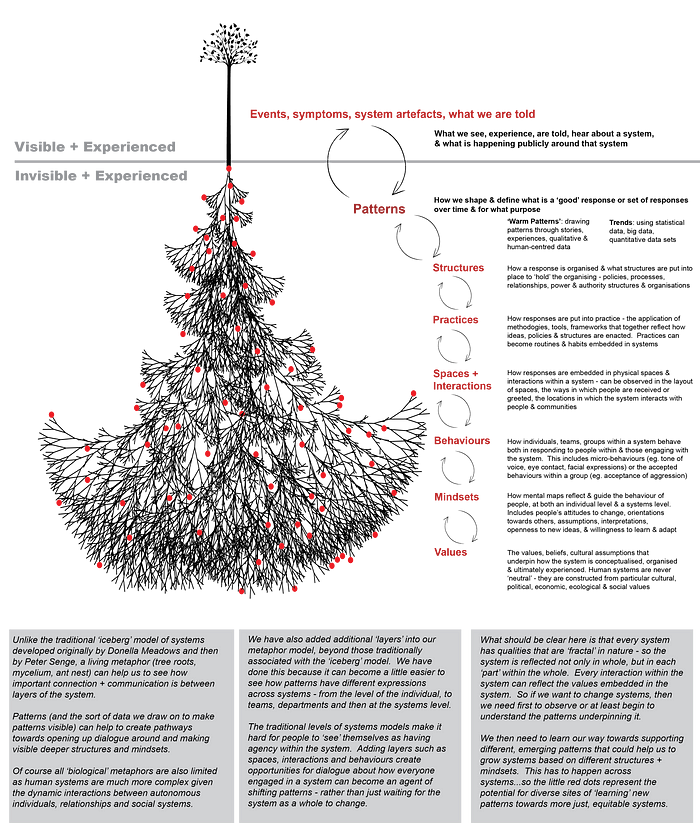

First — what’s a pattern in the context of systems change?

In simple terms, patterns are interconnected behaviours, relationships and structures that together make up a picture of what ‘common practice’ looks like and how it is ultimately experienced by people interacting with and in a system.

If we take Public Services in the twenty-first century here are some examples.

Public Service organisations have most often been formed around concepts such as universal access, service delivery, social safety nets, and public provision of critical infrastructure. Built into these elements are patterns, like:

Patterns of relationships: based on objectivity, universalism, professional relationships.

Patterns of resourcing: focused on rationing, efficiency, programmatic resource flows.

Patterns of power: centred on professional expertise, needs assessments, deserving access to spaces and services.

On the surface, these are not necessarily negative and there have doubtless been many successes enabling broad access to services and infrastructure.

It’s also true though that there remain many who have not benefited, who have missed out on access or opportunity, and who have actually been harmed by and within the system.

What is needed is a foundation for public systems that moves away from goals of access to more and better servicing of communities, and towards goals around learning how we can promote patterns of thriving, aspiration, success and ‘wellbeing’.

The role of everyday patterns in shifting systems

There are a growing number of people discussing the need for systems in many circles — from service providers, funders, investors, intermediaries, and policymakers.

As noted above, most of these discussions focus on the big-picture tasks of pulling various levers from policy changes to new program design.

However, in our work alongside public servants, we have found it just as important to focus on how we shift the foundational patterns, behaviours, relationships and interactions that underlie all parts of systems.

The everyday patterns.

These may look small in the scheme of systems, but actually, they can fundamentally shift people’s lived experience of systems. And importantly — they are within the reach of every one of us who works in a system to start to learn our way into.

Becoming pattern learners to re-pattern systems

If we’re interested in systems transformation we need to become pattern learners.

Humans are extraordinarily good at recognising and responding to patterns. They have always helped us understand, navigate, make sense of and respond to the world around us. Every pattern — every interaction within a system — can reflect the values embedded in that system. So, if we want to change systems, we need first to observe or at least begin to understand the patterns underpinning it. We also need to imagine, learn, test and spread new patterns in order to affect change.

The patterns we present here provide a glimpse of transitioning to more equitable, just and healing systems. They have been developed in a context and are still more like starting points than fully developed patterns of good practice. We see them as prompts that help us to learn, make sense and meaning and deepen dialogue about what it may take to truly create transformed systems for wellbeing in equitable and just ways. We share these patterns to foster collective dialogues about how we can shift systems towards wellbeing, where people and places can flourish rather than just survive.

Over the next couple of months, we will share deeper dives into each pattern, culminating finally in a combined piece of work.

Read the first deep dive: Beyond Services

Read the second deep dive: Starting Differently

The Yunus Centre at Griffith University exists to accelerate transitions to regenerative and distributive futures through systems innovation

Originally published at Medium

featured image found here

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Turning the stone: embedding systems thinking in the everyday

The context

Images

Isn’t it interesting how frequently as human beings we turn to metaphor? Sometimes these images are so embedded in the everyday that we don’t see them for what they are. We talk about ‘just ploughing on’, ‘turning over a new leaf’ and much more. Why? Because we don’t feel, think and communicate solely in mechanistic term, we are not ‘desiccated calculating machines’. We think in patterns, through resonance, emotion, stories and intuitive connection as well as logic.

Metaphor evokes in us things the literal cannot. It uses the poet’s deftness to reduce the messiness of the world, rejects the technocrat’s straight line sketch of reality. Metaphors also offer shortcuts to submerged mental models or situations, containing in their DNA bundles of previous inter-related experience and learning. I find images can be useful touchstones or motifs around which to organise my thoughts or re-centre activity or purpose. ‘Be more water’ etc.

Systems

Given this, it’s not surprising that imagery and metaphor feature heavily in systems thinking.

Over the past six months I’ve been learning about systems thinking approaches as well as systems change — their practical application in the cause of social justice or similar ends. I’ve been exposed to an intoxicating array of philosophies, tools, narratives and claims. Inevitably some have resonated more strongly than others. A couple I have found a bit vague (but probably didn’t understand) and a couple I have found a bit opaque (and definitely didn’t understand).

But the process of learning has been quite liberating. It has given me new ways to think about the universe I exist within; who can ask for more than that?

Imagine if a toolkit existed which allowed you to pick the lock of whatever complex policy or operational challenges you were dealing with that day. But also somehow captured the shifting beauty of a thousand starlings in flight or the majesty of the moss covered forest-as-organism. Something that gave definition and structure to all the intuitive system-craft we develop simply by being tenacious and creative in our work. That to me is the appeal of systems thinking.

Systems change in the everyday

Some of the approaches I have come to know take hard work, safeguarded time and the willing collaboration of colleagues. Others flit around at the paradigm level, triggering unconscious mindset micro-recalibrations. The variety is at times overwhelming.

So when I asked myself what artefact I wanted to produce to mark the end of my School of System Change Basecamp programme I thought I would consider practical ways to weave embed systemic practice into the everyday.

After reflection I concluded first one thing and then another. Firstly, that identifying and developing the mental and behavioural pre-conditions which allow systemic thinking to flourish is probably more important than striving to develop deep technical understanding of specific tools — after all no plants will grow in a barren field, no matter how packed with potential the seed. And secondly that I wanted to use emblematic metaphors to pin down the most important of these core attitudes, from which a number of simple, everyday systemic practices could then flow.

So the three sections below are a simple — and imperfect — attempt at that. Three images to lodge in my head, and perhaps yours too.

The images

Turning the stone

I have a memory as a child of turning a large flat stone in a wood and becoming enthralled at the universe-in-miniature beneath it. Insect life, leaf mulch, moss. The dynamic equilibrium of decay and fertility, death and life.

Although it’s impossible to pin down what systems thinking/change represents to any single person, for me it is a world-view build on a deep curiosity about the universe and our place in it. It’s hard to be open to other standpoints, learn or develop without an open mind (and an open heart too). A sense of ongoing intellectual and social inquiry can turbo-change any job which requires tactical relationship building, political weather reading, policy landscape navigating and hard decision making.

Ways to turn the stone:

- Deliberately immerse yourself in media and news sources you know you’ll disagree with. Take time to mentally articulate why you disagree with the arguments and be wary of jumping to conclusions. This is actually quite hard to do! The voluntary sector in the UK, for instance, has an obvious bias towards the soft left politically but I hear few people challenging the system to actively seek out opposing views and force the remaking of arguments for the full range of world-views. If you find your ideas shored up by the process that’s great — like a vital aircraft component that’s been stress-tested to near destruction in the workshop it is now ready for use in the outside world. However you may find your ideas slowly changing — it’s all part of ‘exposing your mental models to the light of day’ (Donella Meadows). [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- ‘Get the beat of the system’ (DM again) — set up a rolling meeting with an inter-disciplinary cast representing the most obvious system viewpoints around which you are working. Or convene a space with four or five experts from the same discipline. Get a monthly Zoom/Team invite in the diary and the admin load is light. Help set the tone and model behaviour at the beginning then sit back — see what people bring. It’s amazing the insights, thoughts, ideas (and yes rants) people share, once they are convinced of the fact they are within a group of trusted system colleagues, outside the more formal spaces of government forums and rigid agendas. Sometimes this more explorative space may feel unfamiliar so you may need to sell it as an informal advisory group of some kind. Convening isn’t about just ‘doing the admin’ it’s about setting a tone, making people feel valued and respected, ‘holding the space’ and modelling behaviour that you wish to see others exhibit.

Building the spider’s web

There are three basic elements in any system — data points (people, perspectives, organisations, cells, trees), the connections between them and a uniting, animating purpose. My observation from policy work is that too much attention is paid to the things themselves and not enough to the connections between them.

Building a network of contacts — and entrepreneurially convening flexible spaces within it — may again allow you to get the beat of the system and develop a more richly detailed (though still partial) map of the territory. A fancy name for this might be ‘distributed cognition’, but I think of it as building a web.

Ways to build the web:

- At the most simple level it could be consciously focusing on the relational. Almost all roles and ways of exploring the world involve working with and through others so relationships are obviously key. Systems leadership across organisational boundaries is impossible without high-quality, sticky and trusting relationships. These will support all future work from developing shared campaign positions to negotiating the finances of a major joint operational undertaking. Thinking of relational work as the work and not just a means to doing the work might help.[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- If getting into systems change feels a bit like joining a secret society then it follows that you must identify and cultivate your fellow travellers. They will not appear according to rank, status or job description. Some will be formally trained and others not. Carving out space and time is key here, which is why I’ve started some thinking about a systems change learning club with an emphasis on the fun, informal side of systems exploration.

Looking into the pond

Knowledge of self precedes almost all other forms of knowledge. The wisdom of the ages tells us that we must know ourselves before turning to identify problems and solutions in the external world — ‘physician, heal thyself’.

There is no two ways about it — to work systemically is to work reflectively. The whole idea is about taking a step back and what is that other than an instruction for reflection?

The image of a still pond reveals itself to me here. Mirror-like, but not a mirror. A surface broken by debris, imperfectly reflecting a face.

Ways to look into the pond:

- Building simple reflective practice into the everyday. Do you have a key series of meetings or a super important stakeholder relationships to develop? Or perhaps a colleague you are struggling to get on with? Or a knotty policy issue dancing before your eyes? Try journaling. Don’t overthink it, use a physical journal or a note-taking app like Evernote to get some stuff down. This is usually about the wisdom of the moment so try to do it immediately after the event rather than in hindsight (when our brains begin to impose post-hoc rationalisation). I remember doing this after my first board meeting and breaking it into ‘head’ and ‘heart’. The first covered the mental and bodily experience of a potentially stressful situation, the second provides analytic commentary on how events unfolded and how things could be different next time.[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- The pond does not reflect just the individual but the system itself. One of the School for System Change’s systemic practices — which I love — is ‘enabling the system to see itself, hold the whole picture’. Think about the causal chains that (nominally at least) link the key data points within the system you are working on. For me it might be something like: minister is keen on a policy, directs senior officials; officials develop policy framework; resource devolved to local government level; commissioner commissions provider; provider CEO sets out a vision; ops director mobilises a service; practitioners make the magic happen for people in recovery; person in recovery volunteers as peer mentor. (You can make it more or less detailed as you see fit.) Now typically most data points (people in this instance) are familiar with only their neighbouring one or two points but much less so with the ones further up or down ‘the food chain’. Short-circuiting those connections can have powerful results. I recently organised a trip for a very senior civil servant who had taken on the treatment and recovery brief. We brought him, and other officials, to a recovery service in North London to listen and learn from senior public health representatives, local government commissioners, frontline workers and people in recovery. And in that room in Tottenham the system was presented with a mirror and — fleetingly — could see itself and understand its shared purpose. The officials walked away remembering that policy-making is not an end in itself but an embodiment of the social contract in action; communal resource being deployed to high quality create public services. The frontline workers walked away feeling that policymaking at the centre is hard, but has good people attempting to address that hardness. Things click into place. ‘Ah, I get why that join up with criminal justice doesn’t work properly, as you’ve had your budgets hammered’. ‘So that’s what assertive outreach is, I had always wondered’. ‘So which agencies should we try and bring together at a local level to provide accountability back to the centre?’ ‘I can see it now, this is why we do what we do — communities improved, families healed, citizens recovering connection and meaning’.[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Finally I hope the pond will reveal the embedded nature of our locations within multiple overlapping systems. And the see-sawing of feelings this realisation brings — greater understanding, identification of allies and experience of positive change delivering hope and a potent sense of agency on the one hand, awe at the scale and intricacies of the systems which shape the problems we wrestle with delivering a sense of hopelessness on the other. It might be daunting but we are part of it. As one of my co-learners brilliantly put it: ‘I am the system; we are the system’.

Oliver Standing is Director of Collective Voice, the national alliance of drug and alcohol treatment and recovery charities. He is responsible for its day to day leadership and delivery of its main activity – policy and advocacy work to help bring about an effective, evidence-based and person-centred support system for anyone in England with a drug or alcohol problem. Collective Voice also shares good practice and brings together networks across the sector.

Before this Oliver worked for Adfam (the national charity working to improve support for families affected by drug or alcohol use) for eight years, latterly as Director of Policy and Communications. He has a deep interest in systems change, having taken part in the School for Systems Change Basecamp for Health Leaders in 2021, with a particular focus on policy-making in complex environments and driving collaboration across organisational boundaries. https://twitter.com/OliverStanding

originally published at School of Systems Change

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Decentralized organizing: More collaboration, less hierarchy

From organisational governance to mobilising and sustaining grassroots movements, what is decentralised organising and how can this approach facilitate collective but efficient decision-making without management hierarchy?

Decentralised organising isn’t just about delegating tasks and responsibilities. It’s about transparency and openness, including how financial decisions are made and how labour is divided. This approach creates a great work ethic:

- Empowering members to do the work they care about, not just what they’re told to do

- Cultivating a culture of trust, collaboration and transparency

- Incentives are aligned because ownership is open to all

Sounds good? We recently caught up with Rich and Nati from Loomio while they were in London and discussed some useful decentralised organising approaches. Here are some changes you can easily implement to start working more collaboratively with less hierarchy:

Establishing “ground rules”

Norms are informal agreements about how group members should behave and work together, e.g. open, honest, inclusive. Boundaries are behaviours that we want to exclude, e.g. no mean feedback, exclusionary decision-making. Collectively, norms and boundaries can also be referred to “ground rules”.

Take time to listen to each member’s perspective. Then, as a group, decide on what your shared norms and boundaries will be. Finally, have this documented and accessible to all members and new members so that expectations are clear and transparent. This way everyone is bound by the same ground rules.

Communication norms

Open but efficient communication is a cornerstone of successful and strong relationships. It can be built by establishing communication norms and collectively agreeing on what communication tools to use for what job. For example:

- Realtime: like whatsapp chat: Informal and quick, it’s about right now.

- Asynchronous: Email or Loomio. More formal, organised around topic. Has a subject + context + invitation. Can take days or weeks.

- Static: Google Docs, Staff handbook, or FAQ. Very formal, usually with an explicit process for updating content

An understanding of when to use different communication tools avoids clogging up communication channels with unnecessary information. Finally, it is important to support members to learn how to use tools and remind each other gently to build habit.

Sharing is caring

Hierarchy habits such as having the same chair for team meetings can discourage other members to feel that they can bring ideas forward, participate in decision making, and take leadership. It is important to be intentional about the behaviours you want to bring to your organisation or network so that members trust each other and feel comfortable working together:

- Intentionally produce a culture of trust and belonging by sharing power, enabling lots of time for discussion, for natural leaders to be reminded to hold back and let others talk,

- Growing collaboration skills with practice through empathy, reflection and communication. It helps to have 5 mins reflection at the end of the meeting to ask people how they think it went – OR send out an anonymous reflection form just after the meeting to see how it performed against the organisational values.

- Distribute ‘care’ labour: make care work visible so that it can be fairly shared – this includes things like organising biscuits to setting the agenda.

Decentralised organising in practice: The Lambeth Portuguese Wellbeing Partnership

In this next section, we feature the Lambeth Portuguese Community Wellbeing Partnership (LPWP), a grassroots community network of over 40 local groups and community members. Bringing together organisations and people from across the health, social, charity and voluntary sectors to listen and work together, the LPWP is an exciting example of working in partnership through decentralised organising to help the Portuguese speaking community live healthier lives and to remove the barriers they face accessing health services. The partnership are keen to work towards adopting a decentralised organising approach and are on a continuous journey to work towards greater transparency and collaboration to create change.

Their successes and impact so far include

- A Breakfast / Homework Club run in conjunction with a Portuguese Café, a local school, educational charities and the NHS.

- A GP surgery and a voluntary sector organisation carrying out joint assessments of frail and vulnerable patients, with the voluntary community liaison officers providing care-coordination and links into social support.

- End of life and Latin American disability charities working together to modify advance care planning templates, empowering those at the end of life to make the decisions that are important to them.

- Culturally relevant patient leaflets, education videos and an NHS ‘Welcome Brochure’ in Portuguese, informing patients of their NHS rights and self-care options.

- A children’s charity working with scientists, to provide children from vulnerable backgrounds experiences working in science in universities.