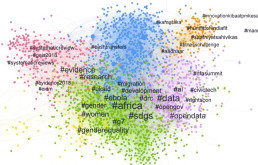

Supporting Evidence-Informed Policymaking: A Case Study in Visualizing Twitter Networks

Claire Reinelt and I worked recently with Sarah Lucas at the Hewlett Foundation to help them better understand and support the emerging field of evidence-informed policymaking. We are excited to share this public report summarizing our findings and methods.

We hope this 20-minute video presentation will be interesting to you, especially if

- you fund networks for social change,

- you design communication strategies,

- you conduct social network analyses, or

- you work to increase evidence-informed policymaking.

The presentation is also available as this 11-page PDF, which has a complete transcript of our narration along with every slide.

If you have any comments or questions about this work, we would love to hear from you. You can comment on this post or email bruce@connectiveassociates.com.h

These two supporting documents help you get the most out of the video presentation:

Originally posted at connectiveassociates.com on March 27, 2019

What’s Our Job?: Getting Clear on Network Functions

April 17, 2019The Field,Network Weaving,Blog

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

As I’ve worked with a variety of social change networks to launch or transition from one stage to another, I’ve been guided by the following formula:

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Form follows function follows focus

My experience is that many groups and initiatives can get very concerned about structure – How will we make decisions? Who will be members? What is expected of them? What do they get in return? These are important questions, and they deserve a fair amount of time tending to them. What can bog many groups down at this stage, however, is that they have not sufficiently sorted out the functions of the network, how it creates value, if you will, which has important implications for form. And if the group is not clear on its focus (purpose, animating goal, mission), this can be that much more perplexing.

So I’m spending more and more time with networks sorting out their core “jobs,” with a few additional guiding mantras, including:

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Do what you do best and connect to the rest.

The value proposition of change networks in my mind is that they add value to a broader landscape of activity, not that they come in and try to take over. Even if this is not the intent, groups can spend little time figuring out what already exists “out there,” what efforts are underway, what other collective efforts are operating. This lack of awareness risks creating unnecessary and unhelpful duplication and competition.

From an ecosystem perspective, each living organism finds a particular niche (what it does best and where) and contributes to the broader whole. I recently met with a network that did some important work sorting out what the jobs of the network as a whole are versus the functions of its individual members. For example, members decided it is NOT the work of the network to create curricula; that’s what members do. It is the job of the network to disseminate these, to make them more broadly accessible and to create a portal that draws more attention to a variety of educational resources that can meet a diversity of needs. Furthermore, the network decided its job was NOT advocacy, since another group already did this work quite well, but it could provide a great service alerting members and others to important campaigns and organizing efforts.

Another guiding mantra:

What value can we create through connection and flow?

There are really the two main ways that networks achieve what are called “network effects” (such as resilience, adaptation, small world reach …). If we are not talking about how a network does its work through leveraging, adding and shifting patterns of connection and flow, then we really are not bringing a network mindset to net work. When we do, this can help illuminate areas for adding and creating value – for example, bridging across various kinds of boundaries, temporal, geographic and cultural, or amplifying otherwise unheard or less resourced members.

Recent work with another network yielded the following list of functions, which they are continuing to play with:

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Build trusted relationships between multiple sectors and communities [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Convene partners across state and sectors [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Generate conversation among diverse partners [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Identify newly arising (systemic) barriers so they can be addressed [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Provide greater access to technical assistanceproviders [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Facilitate access to relevant expertise (including lived experience), information and resources [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Disseminate information about innovative approaches and policy priorities [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Disrupt the status quo in the name of creating system change (ex. support litigation) [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Contribute to movement; use innovation and creativity to inspire people to action [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Curate relevant data, information, planning documents and other resources, and ensure community input is reflected [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

What about you and your network(s)? What functions are you finding add the greatest value? How are you determining what you do best as a network, and where, and how you contribute to others?

originally published on 9/12/18 at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Iniciandose En La CAJA DE HERRAMIENTAS De La AUTO-ORGANIZACIÓN

April 12, 2019Self-Organizing,Blog

Spanish translation by Ulises Aguila

( for the English language version of the Self Organizing Toolkit click HERE )

Iniciandose En La CAJA DE HERRAMIENTAS De La AUTO-ORGANIZACIÓN incluye un conjunto de simples acciones que usted puede tomar para comenzar uno mismo-organización en tu organización o red.

La auto-organización sucede cuando cualquier individuo o agrupación:

- Visualiza una oportunidad para hacer un cambio o tratar de hacer algo diferente [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Siente que puede iniciar una acción[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Encuentra diferentes aliados de redes más grandes para buscar unirse o colaborar

- Experimenta poniendo en marcha acciones pequeñas

- Accede a los recursos que necesitan intervenir[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Pasa el tiempo necesario observando atentamente lo que está sucediendo, resumiendo, aprendiendo de esa experiencia y analizado lo que se ha hecho, todo esto para empoderar de una mejor manera el siguiente paso[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Comparte lo que ha aprendido con una red más grande[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Shakira Hall Louimarre

Shakira Hall Louimarre is a chaplain, higher education administrator and facilitator, committed to developing and cultivating relationships. She connects people, communities and ideas around issues of justice and equity.

Shakira most recently served as CPE chaplain at the RSMC Women’s Correctional Facility at Rikers Island, as well as the Fortune Society re-entry program. Her guiding principles include an attitude of curiosity in the face of challenges and conflict, collaborative and non-hierarchical models of leadership and approaching difference and diversity as a springboard of creative action.

Jamye Wooten

April 10, 2019TeamBlackChurchSyllabus,MLK2BAKER,FreddieGray

Jamye Wooten is a Digital Communications & Social Impact Strategist, Human Rights Organizer and Founder of KINETICS.

On the forefront of digital strategy, his work has spanned the globe – advising nonprofits, faith-based organizations, corporations and individuals in their efforts to engage their constituencies.

In January 2019 Wooten launched CLLCTIVLY, creating an ecosystem to foster collaboration, increase social impact and amplify the voices of Black-led organizations in Greater Baltimore. Wooten is the creator of the #BlackChurchSyllabus #MLK2BAKER and in 2017, launched the Black Theology Project 2.0, a knowledge base system curating theological resources for Black Lives. (TheologyforBlackLives.org).

Emily Carroll

Dr. Emily Carroll is the President and Managing Partner of Janus Analytics, LLC. She earned her Ph.D. in Political Science with an emphasis in Public Policy from Southern Illinois University Carbondale, her MSHS in Public Health from Touro University (California), her MA in Political Science from the University of Akron (Ohio), and her BA in Women’s Studies with a minor in Psychology from Bowling Green State University (Ohio).

During her doctoral program, she worked on several assignments related to government, politics, and public policy for Southern Illinois University as a graduate research and teaching assistant and for the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute as the inaugural Graduate Research Fellow.

Visionary Organizing Lab

Visionary Organizing Lab began in 2016 as a volunteer based project conducting workshops on building beloved communities and a new economy.

Since we began, research across disciplines and the political spectrum has increasingly demonstrated that the global economy is reaching its systemic limits and is in terminal crisis.

Consequently, we are entering a global transition as significant as that from feudalism to capitalism. This knowledge, combined with an evaluation of our pilot, has led us to conclude that we need a consistent research program to fulfill our mission. Visionary Organizing Lab is therefore evolving into a staff based think and practice tank, conducting research on the global economy and on projects that a new system might emerge from.

We will distribute our findings through briefings, publications, short documentaries, and incorporate them into future trainings and workshops.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

What do you mean the global economy is reaching its systemic limits and is in terminal crisis?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Despite the idea that globalization is new, from its inception capitalism has been a global system linking every area of the world in which it is felt. When Columbus arrived in the West Indies, he was laying the initial patters of a global economy. As the Portuguese began to trade enslaved Africans throughout the western hemisphere, these global connections and patterns were deepened. When the British, French, and Dutch began to battle for control over these patterns and connections, the connections themselves became more solid as did the place of North America in this new world. With revolutions in what became the United States and France, a form of representative democracy was born that tied these global economic patterns together politically. Creating laws that enabled economic growth on a world scale, these political relationships between nations created a way to maintain the system’s equilibrium and facilitated the growth of an entire economic and cultural system that eventually came to cover the entire world. We call this system the “modern world-system.”

As long as the world’s industrial capacities remained primarily concentrated in Europe and North America, the system had what it needed to grow and create profits. However, when industrialization spread to the global south and the global north began deindustrializing, it greatly de-ruralized the world, spreading pollution worldwide and employing what had been a cheap, rural reserve of workers.

Consequently, the supply of low wage workers needed to expand profits and the ability of firms to pollute the environment without financial and human costs have both been exhausted. As a result of these trends, we are faced with a climate crisis of epic proportions and the system is quickly reaching its limits for the further accumulation of capital and growth.

Approaching these limits, the system is in terminal crisis, increasingly unpredictable and subject to huge crises and fluctuations. As with all systems in this terminal state, opportunities exist to create a new system(s). Since launching our pilot we have come to understand this historical period as one of “systemic transition.”

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

What do you mean by “systemic transition?”

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

All historical systems have three phases:

emergence, normal functioning, and structural crisis. Capitalism emerged 400-600 years ago, functioned normally from 1648-1968, and entered its structural crisis between 1974-2008. A system enters structural crisis when, typically in response to a prior crisis, its equilibrium shifts too far from its normal center. At this point, a system is increasingly characterized by crises and chaos that can only be resolved by a new system with a new equilibrium.

This period when a system is reaching its limits and the emergence of a new system(s) with a new equilibrium is being worked out is called a systemic transition. Whether we like it or not, capitalism and the entire modern world-system is transitioning into something else because it is in structural crisis. Importantly, its transition presents an opportunity for humans to create a new system rooted in the values of love, dignity, and sustainability.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

So there’s hope? How might we transition into a new, more loving economic system?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Yes, the basis of all our work is hope and a belief that the human spirit is strong and wants to grow and develop. We also believe that the willingness to assume responsibility for systemic transition is something human beings need great support to do. Most of us lack confidence, lack a sense of being powerful, and lack the ability to think in systems based ways. To transition into a new, more loving economy, human beings can and must transform these things about ourselves. Visionary Organizing Lab is committed to facilitating these transformations.

Creating a loving system will require patience, imaginative experiments, and a process of trial and error. Systems emerge very slowly, result from repeated patterns coalescing over time, and seldom emerge from a blueprint. Rooted in visionary organizing, these experimental projects must be designed to meet people’s material and spiritual needs, potentially beginning with questions like, “What effective ways for providing people with a means to sustain themselves other than wage labor might we create or already exist?” or, “What effective ways of community based problem solving already exist or might we create to eliminate the need and justification for police?”

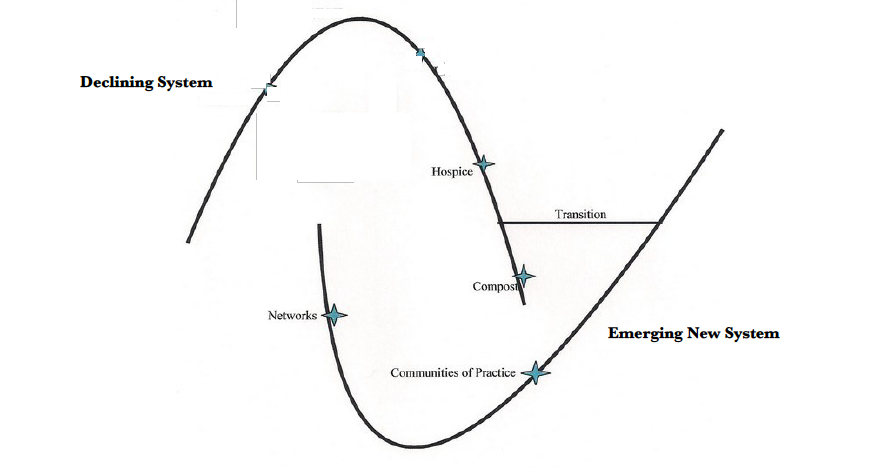

Once experiments have some tangible results, when linked with similar projects, they can form networks of people and projects working to meet human needs absent a culture of domination. Building on these networks, a new system will require the emergence of intentional communities of practice, where knowledge about how to better meet each other’s needs absent a culture of domination can be furthered. At this second stage of a system’s emergence, developing communities of practice requires a group of people who are self-consciously committed to developing a new system.

By continuing and advancing these experiments in communities of practice, these projects can be taken to scale, and the links between them can form what Meg Wheatley and Deborah Frieze have called “systems of influence.” With evidence that this system of influence can meet people’s needs, these once experimental projects can become accepted norms. Transitioning into a new system will require bringing more people into these accepted norms and providing hospice care for the capitalist system, essentially turning it to compost. The diagram below illustrates the emergence of a new system and its relationship to a declining system:

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

What is Visionary Organizing and what do you mean by hospice care for the old system?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

In the same why that hospice care is a means to make someone dying more comfortable, providing hospice care for the dying system involves making life more comfortable for those affected by its death. Systemic transition will be painful for everyone who experiences it. A system in structural crisis is unpredictable, chaotic, and crisis prone. When the economic system that organizes your life goes through structural crisis, life can become increasingly hard. To make that transition more comfortable, hospice care for a dying system looks like basic progressive policies for things like universal health care and guaranteed access to food, water, and shelter.

In contrast to the kind of organizing needed to provide hospice, visionary organizing is a philosophy and practice rooted in the belief that human beings have spiritual and psychological desires to grow in ways made very difficult by capitalism, racism, and patriarchy. Visionary organizing assumes that by starting with a collective vision of what a new world might look like, then working backwards to figure out what kinds of projects might make reality more closely resemble that ideal, people can collectively build a new system under which the human spirit can grow and flourish.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

That sounds nice, but what does it look like?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Visionary organizing looks like living in a food desert and starting to grow food for an entire block using whatever land is available and coming to understand that practice as a potential foundation for a new economic and social system.

Visionary organizing looks like responding to police brutality not only by protest but by also creating neighborhood conflict resolution teams and practicing community based conflict resolution so that people don’t need to call the police to resolve conflicts, and seeing this practice as a potential basis for a new culture.

Visionary organizing also looks like meeting people’s economic needs through things like barter economies, alternative currencies, and community production, and seeing these practices as potential bases for a new economic system. These are just a few examples of what visionary organizing concretely looks like.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

Oh, that approach makes a lot of sense. So what do you do? Why do you call yourself a lab?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

We call ourselves a lab because we experiment with ways to spread awareness of systemic transition and skills needed to facilitate it. Our primary laboratory are trainings and workshops that we call praxis labs.

In praxis labs people collectively experiment with theory, reflection, practice, and the relationship between all three. People are connected to their knowledge of the world around them, supported in understanding how who they are is connected to the larger world, and connect with how they and others might become more human human beings by experimenting with practices that can become a basis for a new system.

For example, a praxis lab on visionary organizing helped Rev. Kelly Steele from Savanah, GA, “to see that our great grandmother’s stories and landscape have direct ties with our current story and landscape,” because “the issues we face today are a direct product of Western imperialism and disconnection from the land, each other, and a sense of community.”

Corbin Leadlein, an organizer and activist from Brooklyn, NY attended four of our pilot praxis labs and came away, “from all of them having engaged in thoughtful, challenging, and inspiring discussions that have helped me to reflect on my role in creating beloved community.

The discussions are participatory, dynamic, and both focus on participants’ personal experiences while also appreciating how our stories fit within trends of historical development. I appreciate that the workshops conclude with participants coming up with tangible actions and projects that can be taken up in their respective neighborhoods and communities.”

To facilitate this learning process, praxis labs create spaces for reflection, conversation, and exchange. In praxis labs we put our reflections on everyday life in conversation with larger structural and historical phenomena. Through that conversation, we create space for people to appreciate their unique capacity to contribute to the world and come to see how personal and larger social transformations are connected.

As the above experiences show, this process creates conditions for people to imagine what we and our communities are capable of, as well as develop practices to facilitate these possibilities and understand their systemic implications.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

That’s impressive. How does the research you propose compliment praxis labs?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

After evaluating our 18-month pilot six points became clear:

People are excited to think through the creation of small projects to build community. It is very easy for people to see these small projects as “feel good” things that lack larger significance. When involved in the co-creation of a systemic understanding of history, people quickly understand that if small projects are networked together they can form the basis of a new system. In co-creating this systemic understanding of history, people quickly grasp that despite their feelings of powerlessness, they actually have great power to create projects and contribute to building a new system.

Despite this awareness of their creative capacity and power, imagining and coming up with actual projects within a systemic context to collectively experiment with is a major challenge for most people. Already existing filmed examples of projects can be useful for imagining visionary projects.

However, because these examples are disconnected from the systemic understanding of history co-created by praxis lab participants, they tend to undermine the kind of systems thinking developed in praxis labs and necessary for the emergence of a new system.

From these six observations, we have concluded that we can best support people in visionary organizing by incorporating examples of already existing projects into praxis labs within the systemic understanding of history co-created in praxis labs. To make our praxis labs more effective, we aim to create short documentaries and publish briefings that place visionary projects in the framework of systemic transition.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

What other roles will the research, short documentaries, and publications play?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Systemic transition is a very difficult idea to grasp and accept. Our hope is that our short documentaries and briefings can make it easier to grasp, accept, facilitate, and live through. By presenting people with an easily digestible picture of the historical evolution of the modern world-system, we hope to provide people with a language to help them understand and accept the crises and transformations surrounding them.

By providing them with a story of people who have come together to build a barter economy or an alternative currency, for example, we hope to provide them with an example of something they can do with their neighbors to meet each others needs without money.

By documenting and promoting the way that participation in these projects has transformed them, we aim to provide people with hope and to support them develop an image of themselves as leaders in the creation of a new system.

We are also planning to use these materials to recruit research and activist fellows, convene conferences, and generally promote the idea of systemic transition and the possibility of a more loving economy and world-system.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

This sounds like a really important project. How might I help? Can I get involved?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

There are several ways you can get involved.

- You can book Visionary Organizing Lab to lead a praxis lab for your organization or volunteer to organize one in your community. We will come to any group of people that want to learn about systemic transition. Booking information can be found at: https://www.alliedmedia.org/visionary-organizing-lab/booking

- You can become a monthly sustainer of Visionary Organizing Lab or make a one-time donation at: https://www.alliedmedia.org/visionary-organizing-lab/donate

- All donations are tax-deductible and processed through our fiscal sponsor, Allied media Projects.

- You can follow us on twitter and facebook, discuss systemic transition with others, and contact us for more information.

Expanding the Benefits of Networked Work

What began as exasperation with dysfunctional organizations and boring meetings became a quest to discover what is possible with collaborative, networked work. My discovery process has led me to see that collaborative learning is what we can put at the center of how we work. We need a way to see how our individual work connects with larger communities and to realize that each of those relationships can be an avenue for information, resources, and new ideas to be exchanged. To help with seeing the relationships and potential for collaborative learning, I have developed this framework:

With good design and facilitation, each

meeting and how we do work can generate benefits and connect learning

within these dimensions.

Below, I highlight the range of benefits that good collaborative work can generate. Many tools and methods are out there for how to do this and I have linked to blogs if you’d like to learn more.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Individual Benefits

- Help me advance the work currently on my plate. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Make new connections and/or strengthen relationships that can help my current or future work. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Deepen my understanding about the community, issues, and/or larger systems I am working within and help me see my niche, e.g., how can my skills best contribute to what is needed in my organization/community. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Access new information and resources; spark my curiosity about new areas to learn about or invest in. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Clarify my own thinking; reflect and make meaning of my experience, e.g., by having an opportunity to talk and be listened to and have meaningful conversations. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Micro-Collaboration/Relationship

Benefits

- Enable people to find each other who have the same or complementary interests. (See Quick Maps, Closing Triangles, and Network Mapping) [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Deepen understanding of other’s work, ideas and perspectives and vice versa (e.g., connecting across siloes, deepening dialogue). (See 1-2-4-All and World Café) [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Create opportunities to spark new “micro-collaborations” (e.g., two or three people working together, meeting for coffee to find ways to help each other’s work, sharing information/making introductions). (See Micro-Collaborations) [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Strengthen trust, care, and good will for each other. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Build skills in listening and collaborative leadership. (See Listening) [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

“It's not just about delivering

content to members, it's about the convening power to help members

discover each other.” - Clay Shirky

Joint Work Benefits

- Access the best thinking of each participant and enable these ideas and experiences to synthesize and cross-pollinate. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Align a group around a shared purpose.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Connect and amplify many voices to have a stronger common voice. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Gather ideas and prioritize them to determine the wisest strategy and actions to take now. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Do more together than anyone could alone. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Connecting Networks and Communities

of Practice

Each member of a

team/organization/network can be a conduit to share learning from

this work into their other networks and learning communities and vice

versa. Here are some examples: (See Invest

in the Field and Peer

Learning Network)

- Teams or organizations can connect to others doing similar work for learning exchange (e.g., community of practice). [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Each role in an organization can connect to learning communities of those who do that same role for sharing best practices and learning (e.g., urban sustainability officers, non-profit executive directors, facilitators). Professional associations, following and sharing on social media, and communities of practice are all places to share learning. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Each team or organization is nested within a larger one (e.g., a town is part of a county, which is part of a state). Insights and learning can be shared within and across these levels.

- Various processes and tools to do work each have networks to share and exchange learning (such as this community of Network Weavers, local Meet-Ups of people who use WordPress, and Art of Hosting, a global learning network of thousands connecting on how to host conversations that matter). [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Collaborative Learning is at the

Center

Each of these four dimensions

contribute to collaborative learning for the whole group and that

learning can generates benefits for each dimension. At each level,

information, conversation, and exchange flow in all directions to

increase the collaborative learning potential of the group.

Learn More

On April 17th, I am providing an

on-line workshop called Working

as an Ecosystem that will offer practical methods for working in

ways that generate these multiple benefits.

Sami Berger

Sami’s practice focuses on developing and implementing learning strategies within networks, collaborative initiatives, government agencies, and non-profit organizations that are striving to make a positive difference in their communities. Since 2013, she has supported them with their evaluation and research needs.

Her current work includes conducting developmental evaluation, qualitative research (including using social network analysis to visualize the networks that she works with), and capacity building to help her clients understand how, why and whether they are making progress.

Blythe Butler

My work is dedicated to building adaptive capacity in individuals, organizations and communities. My approach is rooted in organizational change, network science, strategy development, evaluation & learning methodologies.

I have a broad and diverse background in strategic planning, change management, developmental evaluation, facilitation and organizational development. Over the past 20 years I have worked in the public, private and not-for-profit sectors, consulting with clients in a variety of topics ranging from ISO Quality Management, Process Safety Culture, Corporate Social Responsibility to supporting clients working on social change in the areas of Homelessness, Youth Mental Health, Natural Supports, Early Childhood Development, Climate Change & Environmental Regeneration, Domestic Violence and Collaborative Governance.

For more than a decade I have contributed to the development, design and delivery of the Human Venture Institute and Human Venture Leadership programs (formerly Leadership Calgary). My contributions to this community have deeply impacted my approach to work and life.

Current and past community contributions include: Board Member of the Human Venture Institute (current), Board Member of Bolivia Kids (current); Board Member of Wildwood Playschool (current) past chair of the Leadership Calgary Program Committee and a past Board Member for Volunteer Calgary (now Propellus). In 2008, I was fortunate to be named to Calgary’s 'Top 40 Under 40'. I hold a BComm in Finance and International Development from the University of Alberta, have studied Journalism at Carleton University, Design Marketing at Parsons in New York City and worked as a Page for the Canadian House of Commons.

I live on Treaty 7 lands, the traditional territory of the Nitsatapi, Tsuu T'ina and Stoney Nakoda Nations, and part of Metis Region 3 with my husband and my two children.

"Strengthening the threads tying together our various issues and movements - is, I would argue, the most pressing task anyone concerned with social and economic justice."

- Naomi Klein

contact Blythe: blythe@shaw.ca