For the Sake of Change: Consider the Vastness Not Entered

June 4, 2019The Big Picture,Reflection and Learning,Blog

Two pieces of art have been working me over lately. And I have been sharing them with others in different social justice spaces. One is a poem by Simon J. Ortiz, “Culture and the Universe,” shared with me by Mariana Velez Laris of The Nature Conservancy’s Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Network. The second is the book Race and the Cosmos by Barbara A. Holmes, that I know through the good people at the Center for Action and Contemplation. Both works invite the reader to stretch and open in different ways for the sake of change and … evolution.

Here is Ortiz’s poem:

Two nights ago in the canyon darkness,

only the half-moon and stars,only mere men.

Prayer, faith, love,

existence.

We are measured

by vastness beyond ourselves.

Dark is light.

Stone is rising.

I don’t know

if humankind understands

culture: the act

of being human

is not easy knowledge.

With painted wooden sticks

and feathers, we journey

into the canyon toward stone,

a massive presence

in midwinter.

We stop.

Lean into me.

The universe

sings in quiet meditation.

We are wordless:

I am in you.

Without knowing why

culture needs our knowledge,

we are one self in the canyon.

And the stone wall

I lean upon spins me

wordless and silent

to the reach of stars

and to the heavens within.

It’s not humankind after all

nor is it culture

that limits us.

It is the vastness

we do not enter.

It is the stars

we do not let own us.

Very recently I brought this poem to a group of community organizers from a state-wide political action network, and after hearing it, many said they were really touched by this notion of there being a vastness they do not enter, and are therefore limited by. References were made to systems of oppression, to antagonism, to fear and lack of love. There is so much more to this world and by extension to ourselves that we do not tap into that keeps us repeating patterns of behavior and systems that do not serve our fuller humanity.

“We use language not so much to convey factual information as to construct worlds.”

– Barbara A. Holmes

Holmes’ book extends this same theme of vastness, drawing from the fields of quantum physics, cosmology and ethics as a way of inviting a broader perspective and creating new language and thinking that points in the direction of a world where everyone belongs. She writes, for example, about “dark matter” and “dark energy,” which is pervasive and cohesive in the universe, the essentially creative energy that holds things together. Considering this profound and primordial force, Holmes says, we can only wonder at and celebrate “darkness,” not fear or denigrate it.

Holmes also invites us to consider that physics and cosmology point to the fundamental nature of reality as existing in relationship and interdependence and that systems of oppression go against the grain of the unfolding cosmos. She writes, “Our desire for justice is deeply rooted in systems that are holistic and relational. We have not forced, created, or dreamed this shared destiny; it seems to be the way of the universe.”

In times of breakdown and cynicism, both Ortiz and Holmes tell us that creativity and hope are to be found by looking more deeply into nature and more widely into the heavens to re-member who we are and that there are so many more possibilities than what we have created and perpetuate.

What vastness have you not yet entered, what wonders in our world and beyond have you not allowed to grab hold of you that might liberate and generate new possibilities in your change agency?

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change on March 6, 2019

Header Image by Adam Meek, shared under provision of Creative Commons Attribution license 2.0.

Hand Drawn Mapping

May 31, 2019Network mapping,Blog

Many networks want to generate network maps but don’t have the resources and/or time to invest in computer software of web-based mapping platforms. A consultant to help you generate these types of maps can cost $5-10,000 and take up to three months to survey and map your network.

There is another alternative and I encourage networks to try it. This is to produce simple network maps using Post It notes or by drawing on a large piece of paper.

We have compiled a new free resource module that includes directions for 5 different processes for mapping your network.The direction sheet can help you figure out which process is best for your network. Each set of directions also includes questions you can ask the group to help them analyze and make sense of the map or maps they generate.

The pictures below show examples of many different groups and give you a sense of how different the maps can look!

Although hand drawn maps do not have the detail and nuance of web-based network maps, they do help people visualize their network and start to take responsibility for making their networks healthier and more effective. They can see who is missing and reach out to invite in under represented groups. They can notice if one person or a small group is too central and has become a bottleneck or gatekeeper. They can see types of groups or organizations that are not well-connected.

DOWNLOAD HAND DRAWN MAPPING HERE

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

If you try one of the mapping processes, please let us know how it went. Did it help people in your group better understand their network?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="45px"]

Microtrends To Amplify for Transformation

May 28, 2019Innovation,Network Weaving,Network Support Structures,The Big Picture,Network Structure and Governance,Blog

How does change happen? I saw a book in the airport about microtrends and how they give a glimpse of the possible future. Microtrends are new behaviors, actions or directions that are just starting to emerge but have the energy and excitement to expand into something significant.

I’ve long thought that dramatic and rapid change happens when we see the opportunities in new microtrends and work collaboratively to support and spread those new directions.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Some of the microtrends I see are:

- Antiracism work, dismantling white supremacy culture, understanding structural racism: dismantling Racism - Resource Generationhttps://resourcegeneration.org/wp-content/uploads/.../2016-dRworks-workbook.pdf We can’t collaborate effectively if we don’t know how to be peers.

- Youth leadership: https://climateemergencydeclaration.org/climate-emergency-declarations-cover-15-million-citizens “An estimated number of more than a million people in ca. 130 countries demonstrated at about 2200 events worldwide on March 24.[1][36] “

- New approaches to clothing: “no new clothes” pledges, upcycling clothing, groups making thousands of shopping bags from cloth scraps and used clothing https://boomerangbags.org; https://sew-seamless.com/the-pledge/

- Healing and arts driving change: Resonance Network is convening healers and artists to identify collaborations and ways to build community.

- Governance networks and participation: food policy councils writing policy for city sustainability plans.

- New community places and spaces: maker spaces, community and school gardens, co-working spaces, libraries adding functions like showers and PO Boxes for homeless people.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

What microtrends do you see? Let us know in the comments below.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="40px"]

How can we help these new directions go viral?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Communities of Practice

One of the most powerful ways to amplify an emerging trend is to virtually convene groups or networks around the country (or world) who are working in this area as a community of practice where they can share what they have been learning in their local project(s), get support for challenges and learn more about building expanding networks of networks. This information could then be distilled and shared broadly to other communities so that they can quickly implement and adapt the new strategies.

I feel that supporting these types of communities of practice is one of the most important ways foundations can increase their impact.

Another way to expand your approach is to find other communities who want to experiment and try out your strategy and then set up virtual sessions over a six month period where you can share what you have done. These sessions should also help people plan and strategize how they can adapt your ideas to their community. Having the sessions last over a six month period will give the communities time to try out specific steps, them come back to the group and talk about their successes and challenges. This is like the community of practice idea described above but with newbies. You can do this if you add $15-30,000 to grants you apply for to cover the staff time to facilitate these sessions and coach individual communities between sessions.

Another version of this is to turn what you have learned into products that you can share and/or sell to others. The Food Corridor did this when they developed a Shared Kitchen Management Tool.

Another final way to accelerate the expansion of emerging practices is to provide support for network support structures. In addition to resources for communities of practice, networks around emerging areas need to develop communications ecosystems for expansion. This is a huge gap in that platforms that fully support self-organizing and the sharing of curated information do not currently exist. But patching together the use of zoom, google docs, discussion groups such a Facebook groups or Buddypress, slack and email/enewsletters is a start. Another support that networks need for expansion is training/information in skills such as:

- using self-organizing strategies to expand your network [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Facilitating deep reflection so that your strategy is continually improving and making breakthroughs[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- developing information toolkits from your practice and experience so that others in other communities can adapt your strategy [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Identifying existing networks that may be interested in helping their projects or communities try out your strategies and having conversations with them.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

How do we practice collective leadership when some parts of the leadership development practice feel individual?

May 22, 2019Blog,Network Leadership

Leadership Learning Community has spent a great deal of time and energy encouraging leadership funders and practitioners to expand and evolve their thinking on the very concept of leadership. To think about leadership not simply using what is called the “lone hero” model or lens. When the story of social change is told, it usually involves a few brave men, and occasionally women, who through grit, determination, and perhaps a superpower or two, save the day by individually ushering in change. This approach often excludes many from participating, upholds hierarchical, and often oppressive systems, and is frequently ahistoric, invisiblizing all of the non-household names, often less-privileged folks, who labored to make change possible.

Instead, LLC has supported efforts to think about leadership in more expansive, accessible, equitable, inclusive and democratic ways. Networked leadership is one example, creating a broad base of leadership rather than one leader to lead them all.

But the actual practice of inclusive and networked leadership is challenging. Often, supports are provided to or experienced by individual people, not whole communities, networks or demographic groups simultaneously. Smart and effective leadership processes encourage participants to engage in personal internal reflection, to build authentic relationships with other individuals, attend skills-building training sessions where a person individually chooses to show-up, etc; So how do we practice collective leadership when some parts of the leadership development practice feel individual?

Community Organizers have actually identified many ways to address this complicated challenge, but lately, I find myself thinking more and more about the following 3 approaches.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

Building Collective Leadership: 3 Lessons from Community Organizing

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

1. Grounding Leadership in Purpose, Values and your Vision of the world you wish to create:

In a community organizing context, directly impacted people gather together to change the conditions in their communities: e.g. a dangerous intersection, economic exploitation, inequitable education funding, police brutality, or unsafe drinking water. An organizing effort is guided by collective need and collective purpose, rather than the pursuit of simply a personal change, although significant transformative personal growth certainly occurs. What is important to note is that those involved in Social Justice organizing aren’t only attempting to change the material conditions in communities, they are also attempting to refashion their communities in accordance with a more just vision of the world. I’m not suggesting that organizing spaces don’t grapple with individualism, but it's much easier to remove ego from the equation when the conversation is about a collective purpose to change the world we share, rather than individual benefit.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

2. Embed collectivist and collaborative approaches into the Leadership model:

Community organizers talk and think about power a lot, particularly asymmetrical power. Building collective, rather than individual power, as a way to counter gross power asymmetries is a core concept of organizing. Consequently, collaborative action is both an organizing value and strategy. This doesn’t mean that individual growth and personal relationships aren’t also important, part of the work of organizing is appreciating the individuals within a collective. However, when a community organizer works to support the leadership of a community member, together they deeply explore the greater capacity of people working together. The popular chant, “The people united will never be defeated,” clearly articulates this concept. This is different from a concept of leadership which suggests that if more individual people develop their own skills or abilities, a problem will be solved.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

3. Political education and consciousness-raising:

Effective community organizers create space for people to ask “why” over and over again. Sometimes folks are able to ask “why”, using the circumstances of their own lives as the study material. For example, domestic workers facing exploitation or tenants experiencing yet another winter without heat can ask not only “how can we stop the mistreatment,” or “how do we get heat,” but “Why are our working or living conditions the way they are?”; exploring who is harmed, who benefited, as well as the systems and structures which perpetuate those conditions.

Another effective model is to take a fairly well known historical example. A common example is the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and moving beyond what is common knowledge. In most Black History Month lesson plans, we learn about the Boycott through the Lone Hero lens. But by digging more deeply into the actors (including those overlooked by history books), conditions, leadership development practices, and strategic decision-making processes, we gain a better understanding of the full array of people who contributed.

This practice of excavating both the history and root causes of social conditions is also relevant for leadership development. In addition to “why”, community organizing also encourages people to ask “what”; namely, what would happen if we got together to demand something different? I recently heard Sally Leiderman encourage a group of leadership practitioners to question if their work upholds or interrupts the status quo, or something in between. This, for me, is the most salient question. What would happen if we supported leadership differently, leadership for equity, community building, and love? Exploring what we know about leadership, why we know it and how this understanding shapes our world could help us reimagine new ways of supporting leadership for a more just world.

______________________________________________________________________________

1Shout out to the amazing current and former trainers at the Center for Community Leadership from whom I have stolen different ways of doing this: Susanna Blankley, Joan Minieri, Angelica Otero, Zahida Pirani, Krystal Portalatin, and Hector Soto

Originally published at Leadership Learning Community on 5.6.19

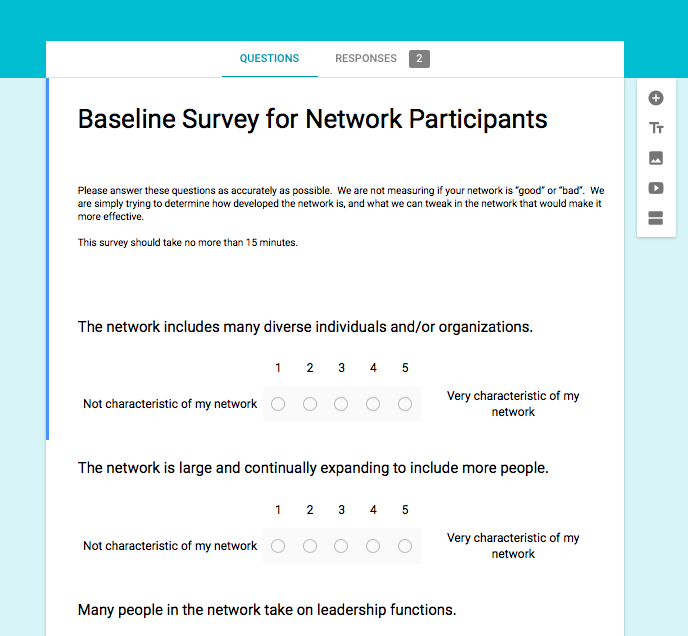

Network Assessment Survey

This week’s free resource is a Network Assessment Survey that can enable you to see how well-developed your network is on several different dimensions:

· How well it creates inclusiveness and relationship building

· How well it organizes collaboration

· How well it helps create alignment

· How effective its support structure is

· How it is structured for participative governance and decision-making

CLICK HERE to download.

MENDING THE COMMUNITY CUP

May 14, 2019Network Mindset,Blog,Systems

For years in conversations in organizations, within advocacy groups, and social change initiatives, I have heard variations of these themes:

- “We know we have to move beyond top-down approaches – how do we get more bottom up input and ideas?”

- “How do we get more diverse voices to the table? We need the input of the grassroots in the room.”

- “How do you engage the people on the ground with lived experience?”

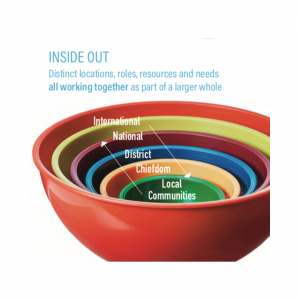

Notice the images within these statements: they imply a vertical hierarchy where there is a top and bottom (e.g., grassroots, on the ground). Hierarchical thinking is so ingrained in our mindsets and how our organizations are set up that it can be hard to imagine another way. Yet, these vertical images are a conceptual overlay on reality. In Donella Meadows’ landmark article Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in System, she described 12 ways to intervene in a system, in increasing order of effectiveness, starting with #12 as the least. Near the top, #2 on her list is: The mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises. She writes: “The shared idea in the minds of society, the great big unstated assumptions—un-stated because unnecessary to state; everyone already knows them—constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works.” #1 is: The power to transcend paradigms.

What happens when we choose different orienting metaphors? I recently had the opportunity to be part of a global learning gathering in Sierra Leone to see first hand a change initiative that intentionally uses specific metaphors and images to orient its work. Seeing these alternatives helped me discover what is possible when we create structures that arise and work from a different paradigm.

Sierra Leone is in West Africa, a country of six million people that endured a brutal civil war. John Caulker was a human rights advocate in Sierra Leone who was involved with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) after the war. In addition to the TRC, Sierra Leone had a Special Court, a hybrid national/international judicial process that indicted 13 people for war crimes. He saw a need for reconciliation work to mend the broken bonds of community – at the community level. John met Libby Hoffman, a US funder with Catalyst for Peace, who had a similar interest in supporting community-level healing and development in a systemic and sustained way. They created a partnership that has worked together for 12 years through a non-profit in Sierra Leone called Fambul Tok, which means ‘family talk.’

Inside-Out Peacebuilding and Development

As a country that had been colonized and then was subjected to aid and development initiatives sent in from the outside or “rolled down” from government, aid agencies, and non-profits, the communities in Sierra Leone had rarely been asked what they needed. To explain how this method of providing aid was actually not helpful, Fambul Tok and Catalyst for Peace developed a new metaphor, as Libby shared at our gathering:

“Imagine a community as like a bowl. Humanitarian aid, whether for peacebuilding, health, education, economic development or any other purpose is like a bottle of water. When there is a crisis, resources get poured into the bowl — but they just go right through. The bowl is cracked. And if you keep pouring water into a cracked container, it widens the cracks and can damage it further — while also depleting the supply of water. Not a healthy cycle for anyone. The community container itself is invisible in the system, and the work of repairing the cracks completely absent. An inside-out approach to peace is not about pouring water into a community. The work is about repairing the container. When the cracks in the bowl are fixed — when a community is healed and whole — it holds water, and the community’s own resources flow over.”

They call this “inside out peace and development.” Fambul Tok’s process was to “go to” and “walk with” communities, listening and building their capacity to plan and implement their own reconciliation and then development programs. The outsider’s role is to encourage, hold space, and accompany, not direct. Forgiving the Unforgiveable is a TED talk by Libby that shares the story of their early work. On Fambul Tok’s web site, they highlight their underlying philosophy: “Our approach is rooted not in western concepts of crime and punishment but in communal African sensibilities that emphasize the need for communities to be whole – with each and every member playing a role.” I encourage you to watch this film about the reconciliation phase of the work.

At the learning gathering I attended, they hosted 100 people from 15 countries for a five-day event, which included visiting villages to see first-hand how the work and spirit had taken root over 12 years. We divided into groups and each group visited one of ten different communities. Each group experienced an unbelievable welcome with singing, dancing and drumming, and warm hospitality. We sat in on their community meetings, led by women’s groups called Peace Mothers that use micro-enterprises to pool resources and generate more wealth with their own local resources. Some began community farm enterprises, while others are doing soap-making. There was a quality of ownership, locally-led initiative, and collaboration toward a shared purpose that moved us all. And there was a real sense of dignity. People spoke of the “mended cup” and said “we are united.”

One of the participants who visited a village said, “I saw the power of metaphor —the way the community explained to us what they are doing was through the story of the broken cup. If you can find a way to explain what you’re doing that is simple and powerful, I saw how extraordinary that can be.”

In communities across the country, they discovered that when the focus and supports were there to allow local people to ensure the “cup was mended,” there was a release of initiative, energy, and resources. The reconciliation work was a foundation that then evolved into vehicles for people-led economic and community development, women’s leadership, and an inclusive people-led planning and governance process. That local planning process is now being adopted nationally in a new framework for inclusive governance and rural planning.

Outside-In vs. Inside Out Approach

A related visual metaphor helps everyone to see how parts of a system can work in ways that encourage health and responsiveness at each level. In an “outside in” approach, aid and direction are separate and not coordinated/driven by the target community.

This report provides an excellent summary of the philosophy and partnership: Building Peace from the Inside Out In it, Libby writes: “In a system that is whole, the varied levels of aid and support are not fragmented and separate from each other and from the target community (an outside-in system), but rather are nested all together as parts of a larger, interconnected whole. Each level is its own bowl—a ‘container’ that holds the highest purpose and potential of that sector or level.

The role of the bowl within (the ‘insider’) is to draw together in honest conversation with peers about needs, goals, challenges, desires, even when that means having ‘frank talk’ about difficult things; to name and claim their own agenda, and to work togeth

er to achieve it.

The role of an external ‘bowl’ (the ‘outsider’) is to hold the space to see, invite and magnify the voice, leadership and capacity of the level within.”

These two metaphors of mending the cup and nested systems can be adopted in many places. For example, in education, how do we shift to seeing a classroom at the center, with the quality and health of that experience being the focus, and other parts of the system supporting that? This view of nested systems is how nature works, and is a similar model emerging in businesses using self-organizing teams, in networked collaborations, and in regenerative design approaches.

For those ready to transcend paradigms of top-down/bottom up ways of working, the model and example of what has emerged in Sierra Leone is an inspiring example to learn from. They are living a new way:

“We are not trying to change the system as if peace and development is something ‘out there.’ We want to live into the system the way we think it should be.”– Libby Hoffman

Originally published at New Directives Collaborative on May 4, 2019.

Photo by NordWood Themes on Unsplash

SHIFTING A SYSTEM: The Reimagine Learning network and how to tackle persistent problems

May 6, 2019Transformation,Innovation,The Big Picture,Blog,Systems

[ap_spacing spacing_height="12px"]

Some problems are simply too big for any one organization. One solution: a network of like-minded leaders working toward a common goal. Reimagine Learning, taking on systemic education issues, offers a successful model.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

In an increasingly complex business and social environment, many are looking for collective solutions to big problems. Networks can address sprawling issues in ways that no individual organization can, working toward innovative solutions that are able to scale.

Fortunately, the collective capacity to address persistent problems is deepening in real and exciting ways. A set of tools, processes, and mindset shifts has emerged to help leaders align a set of diverse actors around a shared understanding of a problem and then create a coordinated plan of attack.1 This approach to large-scale problem-solving is a powerful way to catalyze progress.

Our full-length report, Shifting a system, presents a case study of how a group of leaders and their organizations can coalesce behind a shared vision for change.

The Reimagine Learning network came together to tackle big education issues, ultimately aggregating and deploying US$38 million in philanthropic capital. Over six years, members worked to create teaching and learning environments aimed at helping to unleash creativity and potential in all students, including those who have been historically underserved. The group—launched with 32 members, now grown to more than 700—helped build and scale organizational models that embed a focus on both social emotional learning and learner diversity, ultimately funding 25 organizations that collectively serve 7 million students nationwide.

The experience of Reimagine Learning’s members suggests lessons about effective steps that leaders might take in constructing a network:

- Map the landscape. Reframe the problem. To broaden the aperture of possibility, bring unlikely bedfellows to the table.

- Understand differences. Discover similarities. To shift the status quo, imagine the future you want to create.

- Deepen strategies. Learn by doing. To make collective progress, embrace the intellectual humility of uncertainty.

- Move from curiosity to action. To deepen organizational capacity, nurture individual curiosity.

- Grow the group. Increase impact. To understand network impact, accept a broader definition of measurable value.

- Assess the whole thing and why it matters. To know where to go, assess where you’ve been.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Seeking systemic solutions

In 2012, when Reimagine Learning began forming, the US education system showed serious signs of struggle, with less than 40 percent of K–12 students proficient in math or reading and 1 million dropping out of school every year.2 Meanwhile, 12 million school-aged people had experienced three or more adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction, and 21 percent of all school-aged people lived in poverty.3

Leaders in education had formed well over 100,000 education nonprofits, aiming to address some of the issues, but the scope was simply too broad for any one organization to have a significant impact. In addition, even as a growing body of research highlighted the importance of supporting diverse learners—including students dealing with poverty-related trauma—educators, researchers, and advocates for students with learning and attention issues felt excluded from the general education-reform conversation.4

The Reimagine Learning network was launched to empower groups focused on learning differences, social emotional learning, and trauma. Catalyzed by Boston-based venture philanthropy organization New Profit and US$38 million of funding, this diverse network of change agents aimed to support an approach to education based on a deep understanding of how students learn.

Reimagine Learning’s goal was audacious and desperately needed: to fundamentally reimagine how learning happens for children in this country and to offer a new vision of how to meet the needs of a set of learners typically underserved by the education system. It was a call to action that galvanized people and organizations across the country to participate in a collaborative process to craft a vision and in a strategy to shift a system.

This six-year initiative demanded a major reframe in thinking about the role of education and how to make it more effective. And changing the mindset or paradigm out of which a system arises is one of the most powerful leverage points in a system you can affect.5 But gaining a hard-won mindset shift is only the first step in a journey. In the case of Reimagine Learning, getting to that point took years, and it was only the beginning of the process to get to action on the ground that would drive outcomes for young people and families. What followed was a series of changes—within and among individuals and organizations, in classrooms and boardrooms, at the dinner table and on the floor of the US Senate—that reflected this reimagining, allowing the effort to come one step closer to unleashing the potential of all students.

Participants’ involvement in shaping Reimagine Learning’s vision and strategy prompted them to reshape their own organizations, which collectively serve 7 million students nationwide.6 At its core, engagement in the network succeeded in changing the mindsets of many of its participants, who in turn influenced practices in school districts across the country and created a deeper understanding of what supports a “whole child’s” learning in a classroom.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Stronger together

Obviously, not every organization—or organizational goal—is best served by developing and engaging in a network. It’s a mode of problem-solving that asks leaders to assume a network mindset and demonstrate a willingness to work with and through others.

Ultimately, working in a network requires the integration of three key dimensions: an understanding of human dynamics—the people you need to build solutions and make them stick; an ability to craft collective strategy—getting smart about the problem and developing a point of view and action plan; and developing the right network configuration—designing and weaving a different kind of structure to support a group as it forges its own path forward.

It is a way of working that defies command-and-control posturing, in which insights come from the collective—and connections among them—rather than experts. It’s a journey on which there are no short cuts, and it will try the patience of those tied to short-termism. Yet it is an approach to problem-solving that we hope continues to be tested and developed.

See our full-length report, Shifting a system—a case study developed by the Monitor Institute by Deloitte in collaboration with New Profit—for a full account of how Reimagine Learning’s members came together to accomplish real change.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Originally published 4/29/19 at Deloitte Insights by Anna Muoio and Kaitlin Terry Canver

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

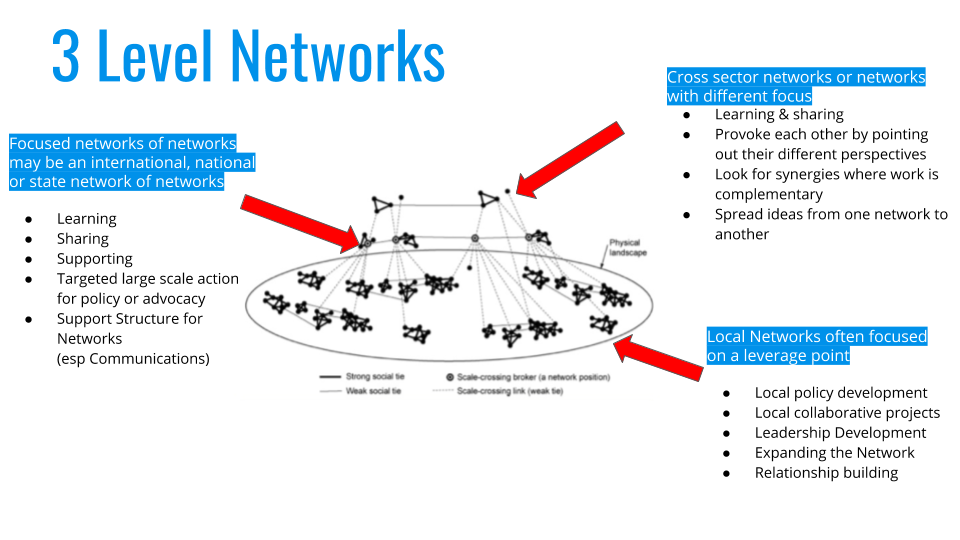

3 Level Networks

May 3, 2019Network Weaving,Network Structure and Governance,Network Processes,Blog,Transformation

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Networks of networks have huge potential. They encourage the kinds of aggregation and numbers that can result in successful campaigns and policy initiatives.

They also can convene innovative projects from around the country (or world) to learn from each other, support each other and provoke each other to expand how they think about what they are working on.

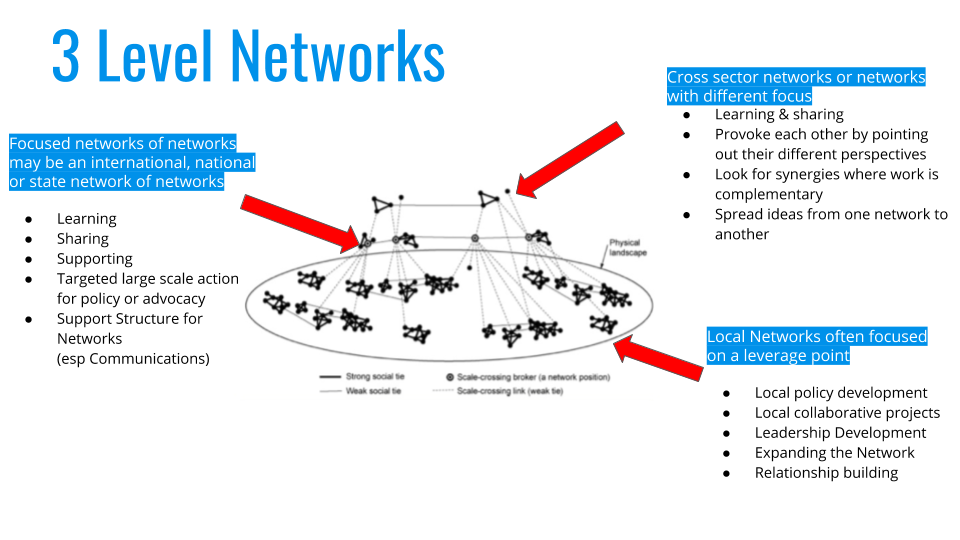

Transformation or system shifting requires networks to be involved in networks of networks. This diagram and activity is designed to help networks develop networks of networks to maximize their impact.

CLICK HERE to access the 3 Level Networks download.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

The Transformative Power of Networks of Networks

May 2, 2019Network Structure and Governance,Blog,Systems,Transformation

Three Level Networks for Transformation

I’ve mentioned before that transformation or system shifting requires networks to be involved in networks of networks. This blog post will explain why every network needs to be part of and explicitly develop networks of networks to maximize their impact.

Networks need to be part of three types of networks, shown in the drawing below.

1. Local Networks

Local networks are networks formed in a particular locale, usually a city, town or in rural areas or a multi-county region.

Often local networks focus on a particular issue area, problem or alternative. Examples range from local food networks and local culture of health networks, to local climate change networks. Although a network may be catalyzed as part of a national effort (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s culture of health efforts, for example), it’s local roots in a set of specific local communities is critical for success.

Local networks are where small but concrete collaborative projects can be nurtured, and where residents can build new leadership skills as network weavers. Each local project is an opportunity to invite in new people and thus expand and diversify the network.

Local networks can also be very effective in advocacy and in policy work. For example, many local food policy councils are writing the food section of local sustainability plans (which city councils are approving with few or no changes).

Many local communities have informal networks, especially among nonprofits. Their staff probably know each other and may collaborate on the occasional project. But any community can become much more effective by making their local network more intentional.

This usually means:

- convening not only area nonprofits, but including government officials and agencies, businesses, and residents

- determining a purpose for the network which is essential to help focus collaborative efforts

- Identifying leverage points where change is more likely to occur

- forming work groups to collaborate around those leverage point

2. Focused Networks

Focused networks are networks, often national (though they may be state, multi-state or international), that focus on a particular issue, problem or alternative.

Often these are branded networks (have a specific name i.e. 350.org rather than environmental network) whose participants are individuals, organizations or local networks. So, for example, the Center for a Livable Future at Johns Hopkins has helped build a national network of local and state food policy councils. They have a lively listserv for sharing information and discussion, and frequent webinars and videoconferences.

Not all focused networks help foster local networks, but when they do, they gain access to lots of innovation and usually find that this strategy enables them to rapidly expand their national network. In addition, when national networks convene local networks, local networks can learn about the innovations happening in other communities and adapt those successes in their networks. So instead of simply focusing on individual local leaders, as many focused networks do, they could encourage and support the local leaders to form local networks. Center for a Livable Future did this by having a series of virtual sessions on how to create local food system networks.

Funders could amplify this catalytic and convening role for national networks by providing funds for Innovation Funds. Summer Matters, a network of summer programs for children, for example, set up an Innovation Fund to encourage their local members to form collaborative projects in their local community. When Innovation Fund projects are convened virtually, they can better capture breakouts and innovations to share with the larger network. In addition, the funded groups form a peer support network which generally last beyond the funded period.

I’d love to hear stories of focused networks that proactively helped local networks form...please share your experience in the comments below.

Focused networks are often able to mobilize large numbers of people and/or organizations to do advocacy or actions, or conduct policy initiatives. However, if they do these in a self-organizing fashion, i.e. encouraging people to work with others on posters for marches or for visits to legislators, and at the same time provide tools and encouragement to continue self-organizing when they return home, they can greatly increase their impact.

3. Networks With Other Networks

Networks can really benefit when they network with other networks. These types of networks help networks be transformative either through their differences or through their power of aggregation..

However, this type of network is most likely to be neglected. These networks can be one of three different kinds:

- networks of networks with a similar focus formed to create the numbers needed for effective large actions

- cross sector networks

- networks that are quite different in purpose but can be constructively provocative for each other and stretch everyone’s world views

Aggregated networks are composed of branded networks that are working on a similar focal area - for example environmental and climate change - who can work together, especially on large-scale actions and campaigns or on policy initiatives, to have much greater chance of serious impact than could result from a single network’s action.

Most of these networks are loosely linked to others like themselves but few have explicitly met to discuss ways they can share information or identify emergent opportunity areas where they might work together. Many aggregated networks are formed for marches, such as the 2014 climate change march in New York City. However, like this one which was orchestrated by a single organization (350.org), the network brought together by this march was short lived.

We strongly encourage national networks to begin reaching out to other related networks and meet as peers not just on joint marches and actions, but to understand the system they are trying to change, determine who is working on what, and figure out how they might have some protocols for sharing information and have convenings to share what each is learning.

This is something I’m particularly interested in working on, so if you are too, get in touch with me at juneholley at gmail.

Cross sector network of networks are when a network invites in or networks with entities or networks from different sectors. For example, a local food network might create a larger network that includes local policy council networks, local food businesses networks such as restaurant associations, farmers, and manufacturers, markets such as schools and hospitals, and government officials and agencies. Including participants from different sectors accelerates shifting of the food economy: the network can help markets and producers better connect, for example, to increase production of local food, or it can create food policy proposals that will be easily approved since a wide ranges of perspectives helped create them.

Another example of cross sector networks of networks are those that form around large landscapes, such as the Rocky Mountains, to develop joint policy and collaborative actions. They work hard to bring all the networks involved “around the table” -- loggers AND environmentalists, for example. Participants in such networks do not have to agree on much, only join together with subsets of the network on projects and sub-projects that serve their interests and priorities.

Networks of networks with different focal areas. This occurs when a network intentionally reaches out to a network with a different purpose or focal area to expand their understanding.

Leadership Learning Community (LLC) recently convened people from a number of different networks in Oakland California. During the gathering a racial justice network interacted with more traditional health organizations, and both benefited greatly from each other’s perspective. In St. Paul Minnesota, a network of public libraries began working with networks working to support homeless people. This resulted in some libraries becoming support stations for homeless individuals - installing showers, lockers and Internet access stations.

Another example is a set of networks who come together around common learning interests. For example, I work with the Resonance Network (working to create a world where all women and girls can thrive) and the WEB Network (well being and equity bridging network supported by RWJF). First the WEB Network met with Resonance to hear “lessons learned” from Resonance during their formation process. What things did they do successfully? What did they wish they had done sooner? Both networks are now sharing what they are learning as they develop Innovation Funds and facilitation pools. This network of networks is expanding as these networks query other networks on communications and governance systems.

4. In Conclusion

Networks of networks have huge potential. They encourage the kinds of aggregation and numbers that can result in successful campaigns and policy initiatives. They also can convene innovative projects from around the country (or world) to learn from each other, support each other and provoke each other to expand how they think about what they are working on.

Unfortunately, few of these types of networks of networks exist. Funders would find it very fruitful to invest in the explicit formation of networks of networks, as it could massively increase learning and impact as networks share innovations and aggregate their power.

In the free resource for this week is a diagram of networks of networks and a set of questions you can use to help your network think more explicitly about the networks of which it is a part.

Please share your stories about the type of network(s) you are involved in the comments below. Or, what type of network of network do you wish existed so you could be more effective?

Header Image by Evie Shaffer on Unsplash

How To Map Networks: Understand Basic Elements Of Networks (Agile Praxis)

April 26, 2019Introductions,Network mapping,Network Weaving,Blog

WHAT IS A NETWORK?

Social networks have existed since the discovery of fire. Although we have always expressed ourselves through language, feelings and body language, and our relationships with others are evident in the networks we make, we are now more aware of this. It is now time to become even more aware of our collaborative power.

Download How to Map Networks HERE