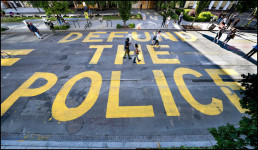

Is Defunding Police Departments Right for Your City?

December 7, 2020Dismantle Racism,Blog,Equity

Is Defunding Police Departments Right for Your City?

Will it Lead to Sustainable Success or Catastrophic Failure?

People around the world are protesting against racism and police brutality. The system is breaking down (or in the throes of self-correction, depending on your point of view). One solution that has been suggested is to defund police departments. It is unclear, however, whether defunding is the best approach for all cities.

Arguments against defunding suggest that it will lead to greater racial inequality and harm to the community as poor neighborhoods organize around criminal gangs. Some fear that removing the devil we know will lead to the arrival of seven that we do not. A wide variety of arguments in favor of defunding range from the relatively simple to the relatively complex. Each of them is claiming that their plan will lead to greater social justice and less violence.

Despite the range of opinions, two things are certain. First, things cannot continue as they are. There must be change and the change must be substantial. Second, the path to change is not clear, there is a veritable cacophony of voices and opinions on which way we should go.

In this article we will briefly explore our chances for successful change based on our existing understanding of the situation. Then, we will suggest a process for moving forward at the local level with a few key points to keep in mind for maximizing our chances for successfully creating communities that are safe, prosperous, and just. The first question is “do we understand the situation?” The short answer is no.

How do we know how much we know?

One warning flag about our lack of knowledge may be found in the halls of academia. A search for scholarly papers on the topic of “defunding police” found only seven publications. Compare that result with a search for papers on “police brutality” which found nearly sixty thousand publications.

Do those thousands of publications provide us with an effective understanding of police brutality? Are we able to eliminate police brutality? Obviously not. So, how do we think that we can solve the more complex problem of defunding police to improve safety and justice in our communities? It seems we have a vast quantity of knowledge, without much quality or usefulness of knowledge.

Of course, the academic world is not the only repository of knowledge. There are several web sites and articles providing suggestions for finding justice by defunding police. These include “For a World Without Police” and “Transform Harm” with more articles published on other sites almost every day. Each is different with alternate suggestions for action ranging from reducing police use of military hardware, to disbanding police departments.

One case that is increasingly mentioned as an example of successful de-funding is Camden, New Jersey. In that situation, however, the police department was disbanded and then re-formed. There is no guarantee that Camden faced the exact same situation as your city or that the Camden solution will prove effective in your city.

While reasonable people might argue forever about the relative merits of the many plans and few examples of success, we cannot argue forever – justice should be swift. However, justice should also be sure. The question becomes, “How can we predict if a plan might work?”

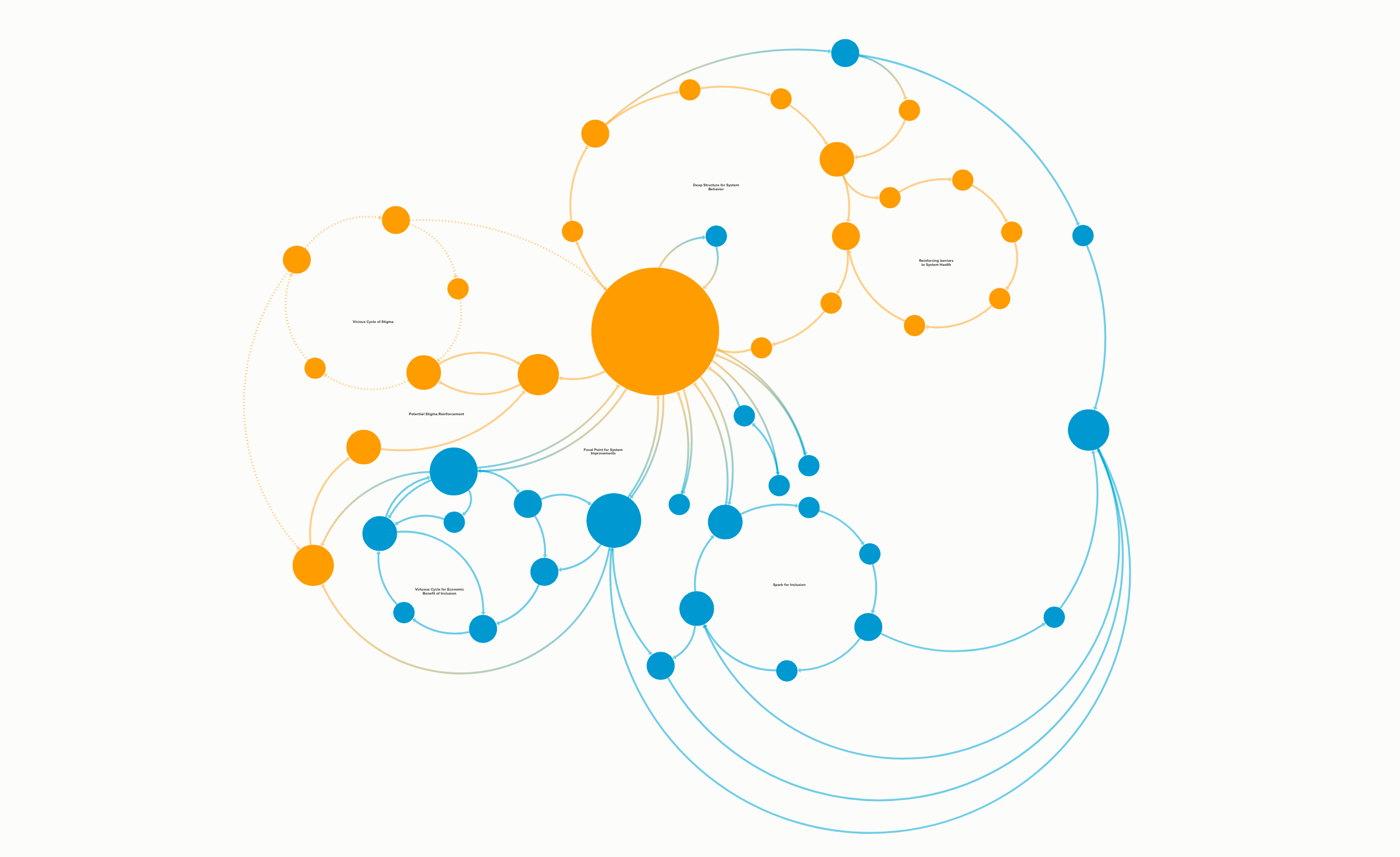

Research in the science of conceptual systems provides a method for evaluating those plans according to their internal logic structures. Let’s look at one, reasonably simple, plan for defunding the police to provide an example of how the structure of our knowledge might be understood. From a recent article we create the following diagram:

Thanks for the free online mapping platform to: https://www.plectica.com

Here, there are seven boxes – each representing a concept that is relevant to the topic of defunding police departments. They are connected by arrows representing causal relationships. For example, the more community patrols in a neighborhood, the less need there will be for police (and, presumably, less violence and more justice for all).

We can measure the structure of this knowledge by first counting the number of “transformative” concepts (those have more than one arrow pointing in to them). Here, the only transformative concept is “Less need for police.” Next, we count the total number of concepts (seven). Then, divide the transformative by the total to get 0.14. Thus, we can say that this knowledge is 14% structured and so has about a 14% chance of success (assuming that each of those causal arrows is supported by good data from previous research).

There is nothing worse than a simple plan.

To have a better plan, representing more useful knowledge, with a better chance of success, we need a map that has more boxes and more connections.

More pragmatically, the structural weakness of this diagram can be seen starting with its “daisy petal” arrangement. Imagine each box is being run by a different organization. All of them competing for funding, each of them ready to take credit for success but point the finger of blame at the other five groups if the plan does not succeed. This arrangement almost guarantees that the many groups will be in conflict with each other instead of cooperating for common and interdependent goals. Because, working in their silos, they are not collaborating as an effective network should.

This kind of “daisy fail” can be avoided by following two parallel paths of developing more structured knowledge on one hand, and by using better tools of government on the other. Both of these require communication and collaboration.

The “tools of government” path means deploying the best approach to find success within each box. For example, to improve our mental healthcare system we might consider providing grants, contracting those services out, mobilizing community volunteers, or any one of many different approaches. The choice of which tool to apply will be based on the appropriateness of that tool to the specific community. That choice, of course, would be made by the careful consideration of a diverse stakeholders. That means reaching out to find an ever-expanding circle of stakeholders and litening carefully to their concerns, insights, and ideas.

The second path is to improve the structure (and so the usefulness) of our knowledge. Here, there are a few basic strategies. First, we want to integrate research from multiple fields of knowledge. As mentioned above, there are untold thousands of research papers available; what we need to do is synthesize them. The second strategy is to access and integrate knowledge from a diverse range of stakeholders (black, white, police, non-profits, government agencies, social workers – more diversity is better). The process of collaborative integration accelerates our shared learning.

While some may see that as a recipe for confusion, their many insights can be integrated effectively using a “practical mapping” approach that has proved effective in creating more structured knowledge. Looking back at the daisy diagram above, we want to understand how all of the boxes may be connected. If we do it right, each organization will be working to support the others; and, will be accountable to the others. In short, creating a collaborative action network.

These parallel paths to success are guided by ongoing research into the “structure of knowledge” that shows how we can develop policies and plans that are more likely to succeed. Also, increasingly researcher are newer “tools of government” that are providing new ways to deal with old problems. Together, these tools, and the knowledge for how they might best be applied in each local situation, suggest a path forward that is likely to have sustainable success.

Instead of advocating for “bandaid” approach devoid of real change, or a “defund the police today” approach of immediate action, we would suggest an approach that is likely to lead to successful change in less than a year as follows:

- Understanding the situation (local facilitators use the practical mapping approach to generate a shared understanding among diverse stakeholder groups and scholarly research).

- Identify where solutions have been found and adapt the appropriate tools for each locality (using the map from step #1, carefully consider the range of tools for each part of the situation and choose the best tool for action).

- Apply solutions in parallel with existing police work (using insights from steps one and two, begin implementing tools being sure to identify how actions of each part will support other parts).

- Evaluate and return to step #1 (this will include tracking measurable results and reporting them with full transparency through community meetings and online dashboards).

With competent leadership, the first two steps should require less than two months each to create an effective map and choose the best tools. With tools in hand and a shared plan, step three may begin almost immediately with activities easily coordinated based on the map. Results may require a few months to manifest; however, they certainly should require less than a year. Data collection will be ongoing. And, with that data, participants can revise the process as needed.

To summarize, we have a great quantity of knowledge but that knowledge is not have a high quality. It is unstructured and so provides only the pretense of understanding. Thus, as it stands, dramatic efforts to defund police have about an 86% chance of failing to reach their goals.

Likewise, it should also be noted, that with less structure and less chance of success also comes greater chance for unanticipated negative consequences. So, the concern about gaining seven devils we don’t know, just to get rid of one we do, seems quite reasonable.

This kind of failure has been seen before. Even policies that are well funded and broadly supported, such as the “war on drugs,” have failed to reach their goals. Worse, they have spawned a variety of new problems such as sending more people to prison which results in increased costs to taxpayers and the destruction of families.

Because action should be taken to advance justice for all, this post has outlined a path of collaborative communication and learning for toward improving knowledge for effective implementation that gives us the best chance for success within a reasonable time frame. The results may not lead to any one group being perfectly satisfied, but they will lead to better, safer, just, and prosperous communities for the benefit of all.

About the Author

Steven E. Wallis, PhD

Director, Foundation for the Advancement of Social Theory (FAST)

Capella University, School of Social and Behavioral Sciences

Researching and consulting on policy, theory, and strategic planning

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5207-603X

Dr. Wallis is a Fulbright alumnus, international visiting professor, award-wining scholar, and Director of the Foundation for the Advancement of Social Theory; researching and consulting on theory, policy, and strategic planning. An interdisciplinary thinker, his publications cover a range of fields including psychology, ethics, science, management, organizational learning, entrepreneurship, policy, and program evaluation with dozens of publications, hundreds of citations, and a growing list of international co-authors. In addition, he supports doctoral candidates at Capella University in the Harold Abel School of Psychology. Following a career in corrosion control engineering, he earned his PhD at Fielding Graduate University and took early retirement to pursue his passion – leveraging innovative insights on the structure of knowledge to accelerate the advancement of the social/behavioral sciences for improved practices and the betterment of the world. His textbook, with Bernadette Wright, “Practical Mapping for Applied Research and Program Evaluation” (Sage Publications) provides unique and effective approaches for developing new knowledge in support of sustainable success for businesses, government, and non-profits programs working to improve measurable results, individual lives, and whole communities.

featured image: DOUG MILLS /NYT

Naava L. Frank, Ed.D.

Naava L. Frank, Ed.D. is a nationally recognized, published expert, with 20 years of experience in the use of communities of practice (CoPs) and networks for non-profits. Naava consults to foundations and nonprofit organizations to launch and support the growth of communities of practice and networks. Her expertise in designing and implementing network evaluation to measure outcomes allows her to maximize the strategic impact for her clients.

Knowledge Communities helps foundations and nonprofits build their capacity to launch and support the growth of networks and communities of practice (CoPs). CoPs use systematic knowledge sharing to focus on improving professional practice.

June’s Personal Ask

November 30, 2020Network Weaving,Blog

The networkweaver site has been a gift of love to all of you who have been working so hard to engage people in co-creating a world that is good for all of us.

As many of you know, I have been practicing (and learning from) network strategies for almost 40 years -- and have gladly shared what I have learned with you on this site!

So many of you have contributed to this site as well -- sharing your experience in the blog or contributing new resources.

Now that I am spending all my time writing, I won’t be able to continue to finance this site.

Leadership Learning Community, a collective that has played such an important role in developing the field of network leadership centering equity, has agreed to continue the site...but needs to raise the funds to continue.

LLC is an excellent fit with the values of networkweaver: they center equity and a leaderful networked approach to leadership; they see networks as a critical path forward; and their mission is aligned closely with ours.

I’m wondering if you would consider donating so that we can continue this site.

Some of you may wish to be a sponsor of the site, contributing $500-$5000 a year, and having your logo listed in a section of sponsors. If so please let me know!

In addition, if you know of funders or donors who might want to sponsor the site, please let me know or contact Ericka Stallings: ericka@leadershiplearning.org or Deborah Meehan:deborah@leadershiplearning.org directly.

Finally, if you can forward this message, or share the donation link, or this blog, to those you think might support us, please do.

Thank you,

June Holley

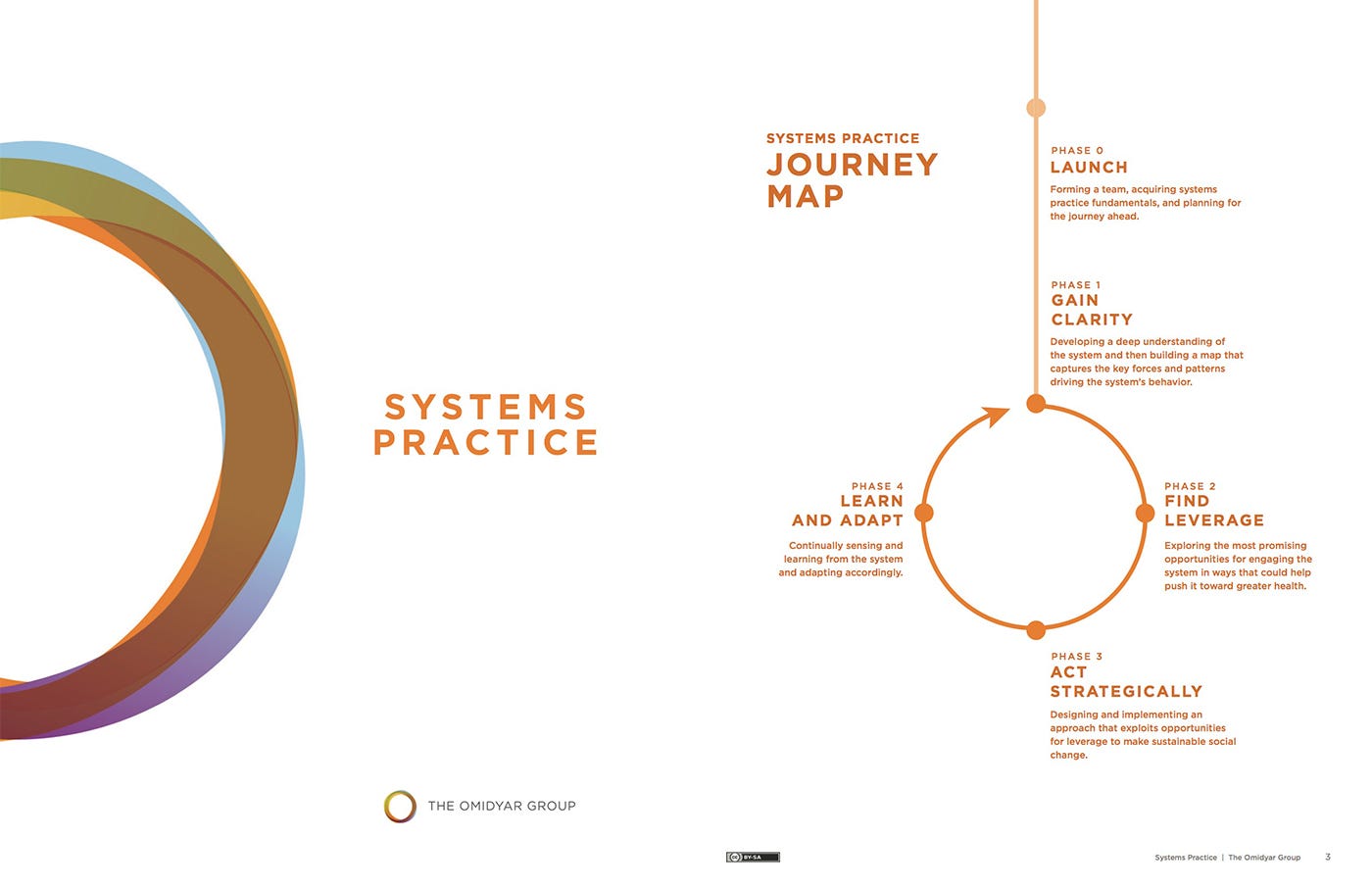

Systems Practice, Abridged

November 10, 2020Systems,Network mapping,Blog

When you’re making a system map in Kumu, it’s important to have skill and familiarity with the tool itself, but it’s equally important to have an understanding of the concepts of systems thinking.

You can learn these concepts and learn Kumu at the same time if you follow the Systems Practice methodology developed by The Omidyar Group. When we’re mapping systems ourselves, teaching systems skills, or simply brushing up on our own skills, this methodology is one of our all-time favorites.

Notably, though, the Systems Practice methodology is time-consuming. The workbook itself is nearly 100 pages long, and it mandates weeks, if not months, of study and stakeholder engagement.

For serious system mapping work, spending this much time studying, thinking about, and mapping your system helps ensure you are addressing root causes rather than instituting quick fixes. In the long term, the time and resources you invest in Systems Practice will pay dividends.

But what if you’re not quite sold on the Systems Practice methodology yet? What if you haven’t encountered systems thinking before and just want to dip your toes in? Or what if you’re an expert or an educator with only a few hours to introduce Systems Practice to a fresh new group of systems thinkers?

At Kumu, we face this problem all the time! Whether we’re doing a product demo, giving one-on-one support to Kumu users, or leading day-long trainings, we rarely have more than a few hours to introduce Systems Practice, introduce Kumu itself, and get as close as possible to the first draft of a system map.

Give those constraints, and after plenty of trial and error, I’ve settled on an abridged version of Systems Practice that fits comfortably into a 2–4 hour session. In this article, I’ll share the main concepts and activities that comprise “Systems Practice, Abridged,” organized into the following sections:

- What is a Systems Practice? [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- The power of mapping with Kumu [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Applying systems thinking [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Incorporating others’ perspectives [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Leverage and learning

What is a Systems Practice? (15–30 mins)

Under time pressure, I gravitate toward a short and snappy definition of Systems Practice:

Systems Practice is a methodology for solving complex problems.

This definition is such a barebones collection of words that, at first glance, it hardly seems to do justice to the power and promise of Systems Practice. But, digging deeper, I think it unpacks nicely:

Systems Practice is a methodology…

Systems practice is decidedly not a simple tactic; it’s not something you can accomplish in a day; it’s not a band-aid or a quick fix. It’s a methodology composed from a full suite of techniques for studying and describing complex systems, then identifying appropriate actions to take to ensure that certain system dynamics persist and others fade away.

…for solving…

Systems Practice has a clearly defined outcome: solutions to your problem. Gaining knowledge and insight is a beautiful thing. I have a huge soft spot for research, data collection, experimentation, and analysis, but even I know that knowledge without practical action won’t help us address the major challenges of this century and beyond.

…complex problems.

Systems practice isn’t appropriate for all problems! It’s appropriate for complex problems, which you can identify by looking for the following characteristics:

- Understanding of the problem is low. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Consensus about what to do in response to the problem is low. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- The problem is not self-contained. It’s intimately connected to a dynamic and changing environment that is outside of your control. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Your intention is to make long term change rather than achieve short term goals.

The power of mapping with Kumu (30–60 mins)

A system map is one of the main deliverables that Systems Practice produces, and its purpose is not only to help you understand the context and identify potential solutions, but also to document your thoughts and decisions along they way.

Kumu is a tool for creating digital system maps that not only show the intricate structure of systems, but also allow you to create profiles, rich with metadata, for each of the factors, connections, and loops in the system. This approach encourages you to draw conclusions from the overall structure of the system, but still provides a great home for more precise information gathered from people with real-world experience in specific areas of the system.

As you implement a long-term solution, you’ll continually be able to return to the map to remember why a certain process or program was put in place, how small actions relate to the bigger picture, and what assumptions did or did not factor into the original decision-making process. Very important stuff!

That said, you don’t have to be a Kumu expert before you start working through the Systems Practice methodology. If you’ve never used Kumu before, there are only a few basic concepts you need to know that will help you dive in — I like to call this collection of concepts “Kumu 101”:

How do I get started with my first Kumu project?

I recommend working through our First Steps guide, which goes through everything you need to know to hit the ground running.

The First Steps guide will teach you how to pick a template, how to start building your system inside the map, how to design and customize the map, and how to invite other people to help you out.

Where can I go to learn more about Kumu?

To help you learn more about Kumu, we put together some great resources. First and foremost is our documentation website, where you can find guides on everything there is to know about Kumu.

You can also subscribe to this blog, check out the In Too Deep podcast, and follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Linkedin!

If I get stuck, where can I go for help?

If you get stuck and need advice, feel free to email us at support@kumu.io, or post in our public Slack workspace at chat.kumu.io. And if you have awesome work to share, we’d love to see it in either of those channels!

For more info and inspiration on what I like to cover when introducing Kumu and system mapping, check out our blog post on Kumu 101.

Applying systems thinking (30–45 mins)

If system mapping is the science of Systems Practice, systems thinking is definitely the art. Identifying a system’s factors, relationships, and feedback loops, with all of their categories, subcategories, archetypes, and metadata, is a complex process and will be a unique experience for each individual system you study.

Even so, there are a few tactics you can use to apply systems thinking and extract factors, relationships, and loops more quickly:

Define a guiding star and a near star

Your guiding star (you’ll likely have one) is the answer to the question, “What healthy, future system is your team passionate about working toward?” and your near stars (you’ll likely have more than one) are the answers to these questions:

- What have you learned about how to be effective in your sector? For example, what have you learned about how to counter human trafficking/ slavery? [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What outcomes are most important to your organization? For example, do you have organizational beliefs or values that cause you to prioritize specific populations or parts of the world or communities? [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What sub-sectors or outcomes play to your team and organization’s strengths (e.g., capacities, knowledge, networks)? [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What trends, research/new findings, or bright spots have you seen that point to promising approaches?

Another helpful framing idea: your guiding star is a broad, ambitious goal that will take 7–10 years to achieve, and near start are impactful but narrower goals that take 3–5 years to achieve.

Your guiding star and near star will often become the first factors that you add to your map.

Start with abstract categories, then get more specific

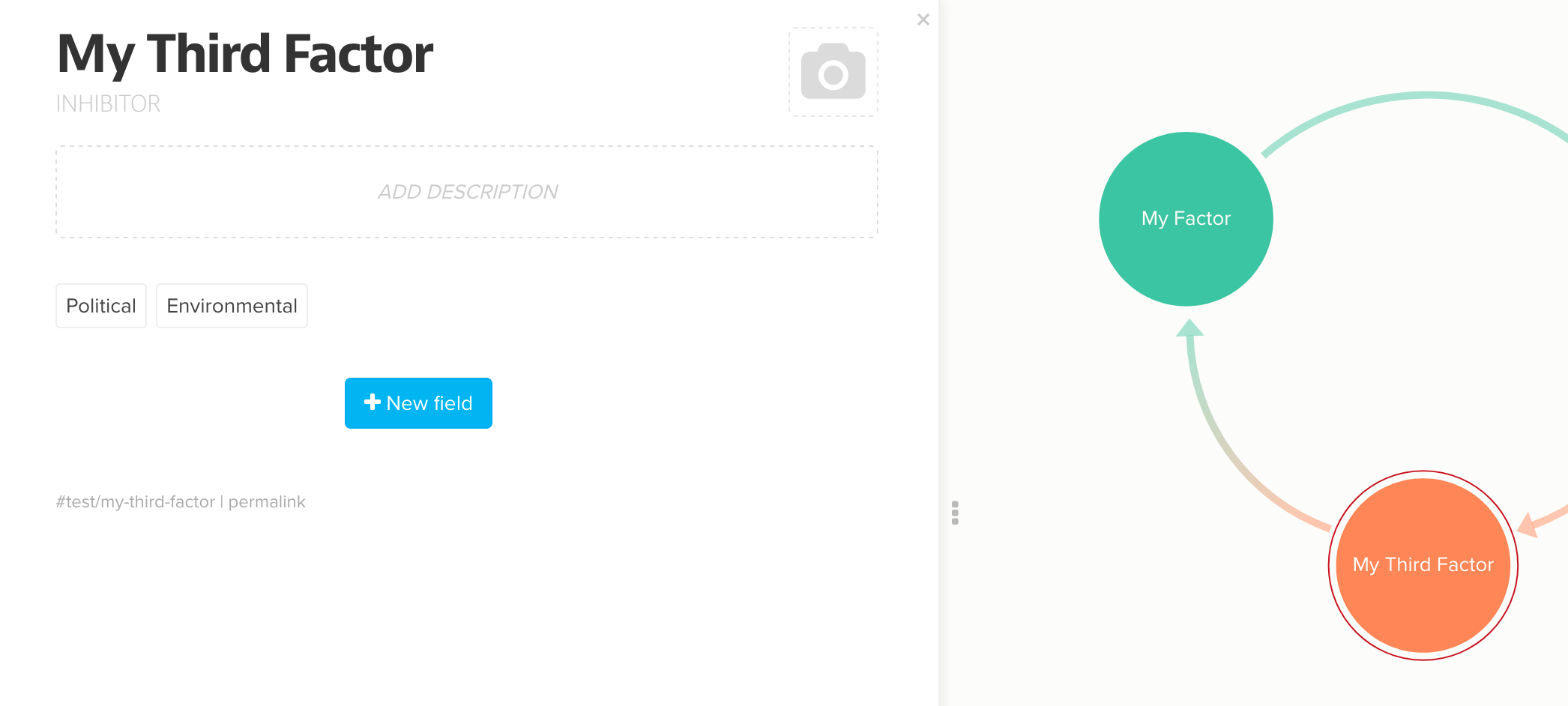

In the System Practice workbook, there’s a great activity that involves identifying “enablers” and “inhibitors” in your system. The workbook gives excellent definitions for these terms, so I’ll quote directly:

An enabler is a significant force in the environment that supports, encourages or increases the health and effectiveness of the system as defined in your guiding star.

An inhibitor is significant force in the environment that undermines or prevents the health and effectiveness of the system as defined in your guiding star.

In my experience, the “enablers vs. inhibitors” categories are superbly useful, but not necessarily because those categories exist in every system. Rather, the simple act of defining any abstract category of factors makes it easier to fill up the map with concrete examples.

Use the enablers/inhibitors dichotomy, or come up with your own categories (e.g. political, economic, social, environmental, and technological), then let those categories guide you toward specific factors that actually exist in your system.

Pro tip: If you’re adding factors to your Kumu map while you brainstorm, take a second or two to open the profile of each factor after you create it and add its category to the “Type” field (just underneath the label). Or, if your factor can fall into more than one category, add all of its categories as Tags:

Write a few paragraphs describing the essential narrative(s) of your system

Tell a few stories about your system, describe both the challenges you perceive and their potential solutions. If you’ve already added some factors to the map, incorporate those factors into your paragraphs.

Once you’ve written your paragraphs, the real work begins: translating your words into cause and effect relationships. There’s a trick to doing this well: the relationships will be hidden in the the verbs you used to describe your system.

Some relationships will be easy to find:

- Factor A increases the likelihood of Factor B

Given that sentence, you can confidently draw a connection from Factor A to Factor B on your map. But in real prose, causal relationships will usually be a little more difficult to find — they’ll be spread across multiple paragraphs, hidden by fancy sentence structures, or split up by interjections and asides. They’re also likely to use more creative words than “increase”, for example, “A is key to B,” or “In order to have Y, we need to have X first.”

If you get stuck on a factor that doesn’t seem to have any connections, just ask yourself:

- What increases/strengthens/leads to/creates this factor?

- What decreases/weakens/detracts from/destroys this factor?

Each new answer you find will be another connection for the map.

Look for loops

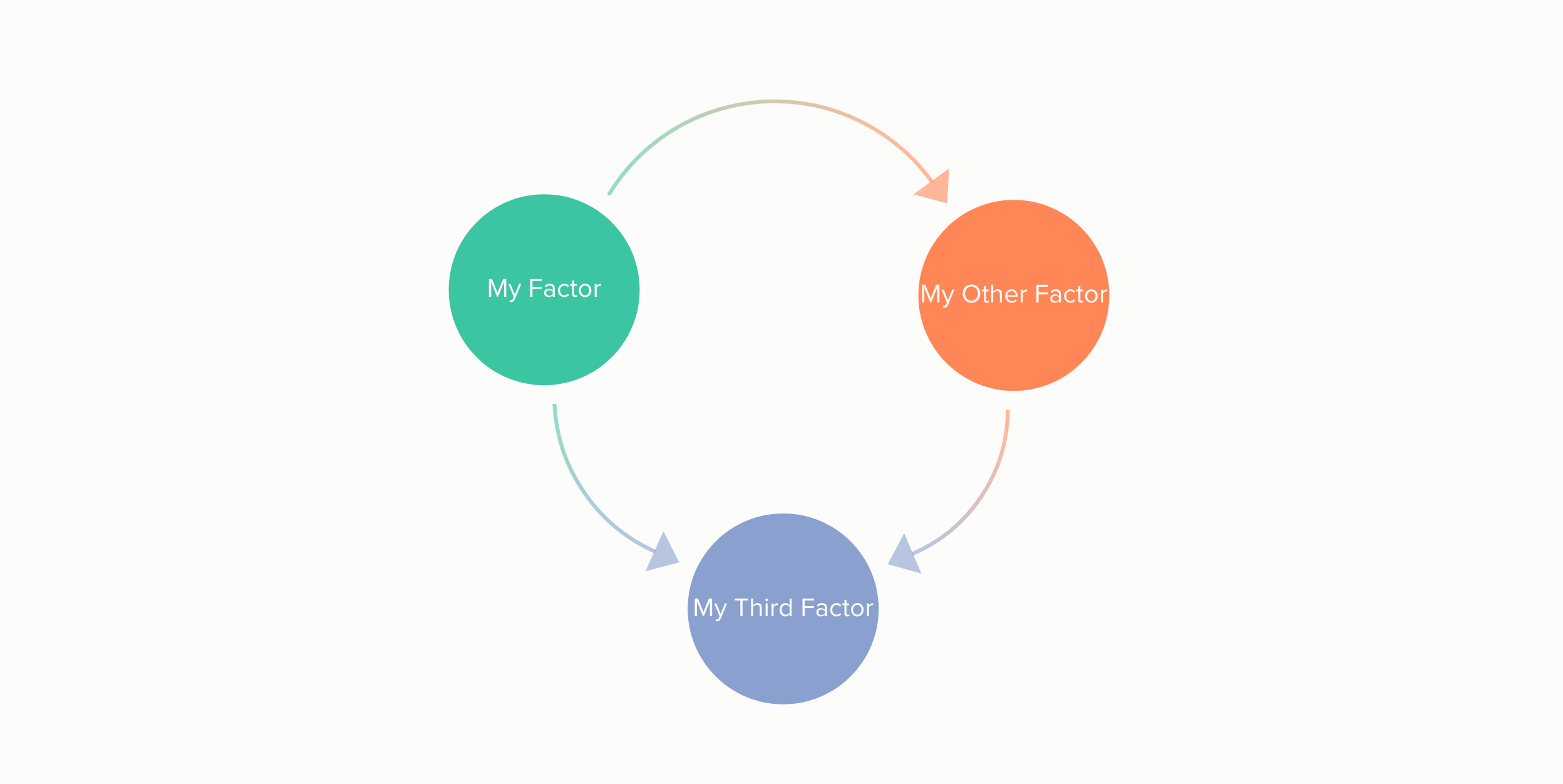

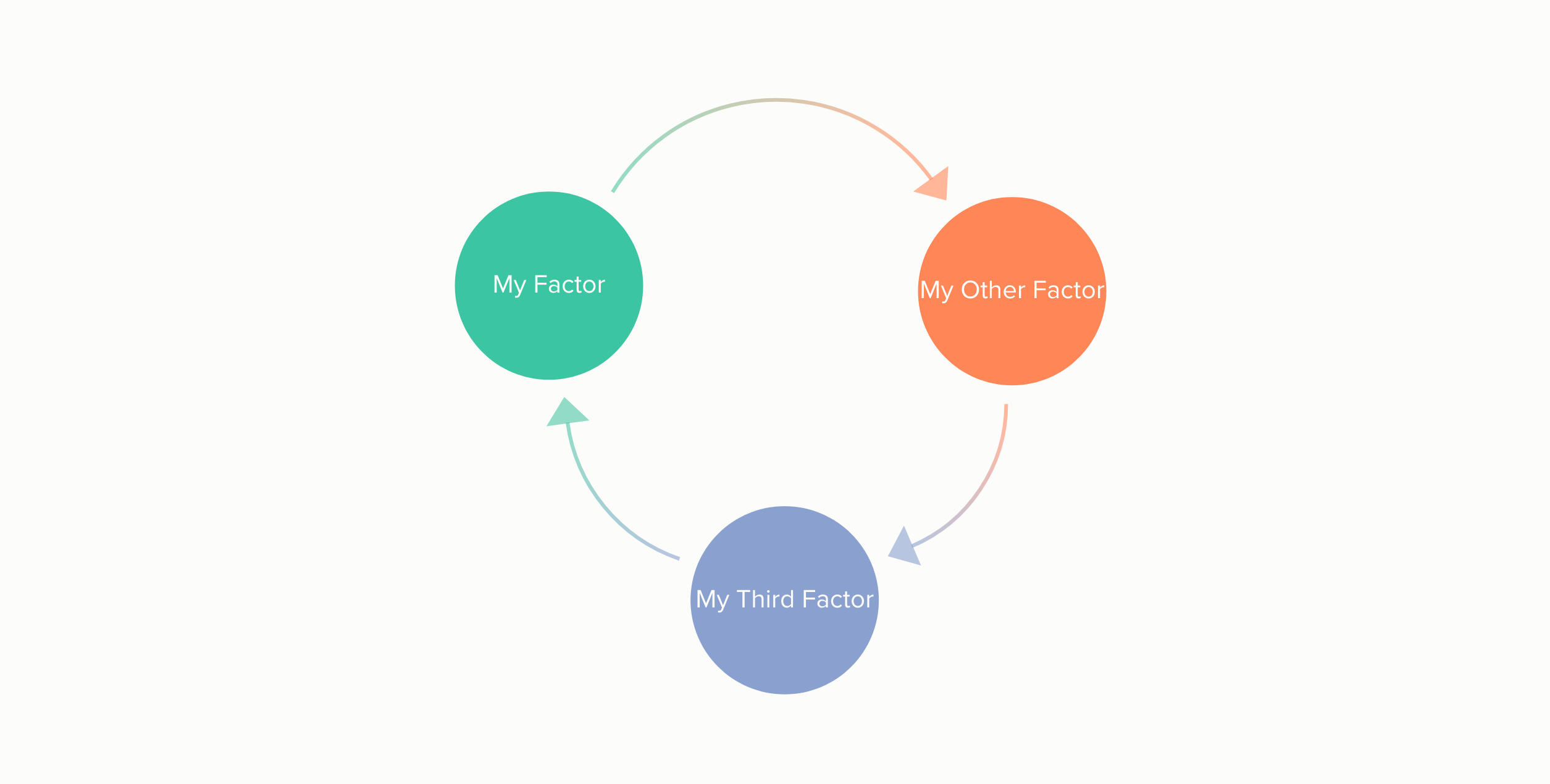

Colloquially, you can use the word “loop” to describe any kind of line that curves around in a circle or an oval. When you’re mapping systems in Kumu, you’ll find many groups of connections that meet that definition, but they aren’t necessarily the loops that a Systems Practitioner is looking for.

In a system map, my litmus test for discovering loops is to ask the question, “If I follow the arrows in this group of connections, can I get trapped?” If the answer is yes, I’ve found a loop, if not, the structure is not a loop, but might still be complex enough to deserve some further study.

Here’s an example of a structure that looks like a loop, but is not, because no matter which arrow I follow, I always end up at the same factor, escaping the trap:

On the other hand, if I reverse just one of the arrows in the structure, I inevitably get trapped going around and around in a circle:

This is the kind of loop we’re looking for in Systems Practice. It’s rarely so simple — in many cases, your loops will contain more than three connections, and they likely won’t be laid out in such a nice, circular shape.

But, after you’ve gotten a few practice rounds under your belt, I’m confident that you’ll have no trouble picking out groups of connections that cycle you through the same factors, over and over again, repeating the same dynamics, cycling through the same factors, over and over again, repeating the same…ahem. Moving on!

Incorporating others’ perspectives (45–90 mins)

If you’re going solo on your system map, hats off to you! It takes guts to try and understand a complex system all on your own. We invite you to return to this article anytime you need some extra guidance, or, if you need help, reach out to us in our public Slack workspace at chat.kumu.io.

If you’re working with a team, you can incorporate their perspectives into your Systems Practice with a simple team activity:

- Designate someone to be your Kumu mapmaker. This person should have a solid grasp on the concepts covered in the Kumu 101 section of this article. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Everyone else can take turns identifying factors, connections, and loops in the map, using the tactics described in the Introduction to Systems Thinking section of this article, while the designated mapmaker adds them into the Kumu map.

I’ve found that it’s fun and helpful to set a limit on how much each person can contribute — for example, set a rule that each person can add 3 items (i.e. factors or connections) to the map, or they can take a stab at identifying and naming one loop. After someone hits their limit, move on to the next person and get a fresh perspective!

Leverage and learning (30–90 mins)

If you work through everything I’ve outlined in this article so far, you’ll have completed only two of the five total sections in the Systems Practice workbook. Clearly, there’s much more work to do!

The final three sections of the workbook teach you how to:

- Identify actions you can take to make change in your system [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Strategically take those actions [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Learn from the results of those actions [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Adapt for the future

This work is very complex and important, and it’s arguably irresponsible to undertake it after only a few hours of systems study. But, in your abridged Systems Practice session, I do think it’s possible to sketch out an action plan, if only to familiarize yourself with the remaining steps of the process.

With that in mind, here are a few practical things you can do with your remaining time:

Identify leverage opportunities

In the context of Systems Practice, a “leverage opportunity” is an action that strikes a balance between feasibility and long-term positive impact in your system.

Explore that thought for a moment: acknowledge that there are many possible action you could take that will affect your system. Some of those actions require very little investment of time, talent, money, technology, or any other resource you have access to, and some require much more than the resources that are available to you. Some of these actions will create huge positive impact, some will create small positive impact, and some may even create negative impact.

More often than not, the actions that create the largest and most positive impact are also the least feasible.

To identify leverage opportunities, start by brainstorming actions you could take, anywhere in the system. Once you have a robust list, evaluate each action, and make explicit predictions about what type, quality, and quantity of resources each action requires, as well as what size of impact each action will make, and what potential ripple effects it might cause.

Narrow your list of actions down to include only the ones that seem to strike a balance between feasibility and impact. Remember that this is a judgement call —your system map and your feasibility & impact predictions can guide you, but at the end of the day, only you can decide which actions are worth pursuing!

Make a measurement and learning plan

You now have some pretty detailed predictions about how your leverage opportunities will affect you and your system, but how will you know if they come true? By measuring the effects!

In any system, the first actions you take are almost always imperfect, and you’ll need to learn from those imperfections, then pivot and adapt. Before taking action, you’ll want to have tools and processes in place to measure the effects, so that the next iteration will be even more successful.

Remember, the basic metrics we’re interested in are:

- What type, quality, and quantity of resources each action requires [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What magnitude of impact (positive or negative) each action will have [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What results will emerge from the ripple effects caused by your actions

You can definitely add to that list as you see fit; every system will have unique measurement needs.

Once you know what metrics you’re interested in, commit to measuring them regularly — keep a journal, make a spreadsheet, talk into a tape recorder, build a robot that follows you around and watches everything you do — whatever it is, just make sure you’re measuring!

Most importantly, make an effort not to take these measurements alone. They are often subjective and tricky to pin down, so be sure to work with a team, interview stakeholders, and in general, involve other people and their perspectives in the measurement process.

Get ready for round 2!

I mentioned that Systems Practice is a methodology for solving complex problems, but you should also know that it’s a cycle.

As you act upon your system, you’ll change it, and those changes can be drastic, extremely subtle, or anything in between. When you observe changes in your system, you should return to your system map and update it to reflect the new real-world dynamics. After you update your map, you’ll of course need to rework your leverage opportunity predictions, and you may need to update your measurement strategy, too.

In short, the Systems Practice methodology requires that you continually revisit its techniques and tactics in order to adapt to your changing world.

That’s the essense of Systems Practice, Abridged! The full Systems Practice workbook is extremely well designed and well written, so we recommend working through it when you have time, but we hope that Systems Practice, Abridged can serve as a comprehensive overview for you or for any soon-to-be systems thinkers you’re teaching.

If you’d like to dig deeper into Systems Practice we encourage you to enroll in the Systems Practice course on +Acumen!

Originally published at Kumu.io

Frontend Developer at Kumu

I'm passionate about software development, data visualization, and applying science and technology in the majority world

How to Reduce Stress and Increase Learning: The Power of Professional Networks During COVID

November 4, 2020Blog,Self Care,Network Weaving,The Big Picture

“I am a nervous wreck, I am way behind on my fundraising, my staff is not getting along, I don’t know how to support them, I lost a major donor, and I feel so alone,” said Aron, an Executive Director of a nonprofit, a few months into COVID.

After almost eight months of the pandemic, leaders like Aron continue to face shifting contexts and ongoing stresses as they try to move into the new normal. Never before have leaders of Jewish organizations had to address questions like making working spaces safe from COVID and working entirely virtually. It’s lonely at the top anyway, but facing challenges further isolates leaders. “I must be the only one to experience this,” they think and therefore hesitate to share struggles with others, who could help. At this juncture in our communal lives, and as the Jewish Federations of North America 2020 General Assembly convenes virtually this week, we see professional networks are critically important to support leaders.

As Bill Gates writes, when tackling a big challenge he begins by asking, “who has dealt with this problem well? And what can we learn from them?” As guides and facilitators to groups of leaders – Ziva organizes leadership development cohorts and Naava guides Communities of Practice – we see the power of networks for leaders in both the Jewish and non-Jewish sectors. Peer support offers leaders practical insights as well as inspiration and hope, through seeing the successes, failures, and resilience of others. Therefore, a combination of peer community and access to an ongoing flow of information and solutions provides leaders with what they need to face the dynamic and ongoing challenges that COVID presents. Aron, for example, had a network but he had not used them much before. They had monthly webinars that provide interesting case studies. But that’s about it. And, while it’s tempting to hope that information is enough to address leaders’ needs, there are a few key pitfalls in that approach.

Overcoming the Challenges of Stress and Isolation

We are learning from new market research by the Schusterman and Jim Joseph Foundations that the key to successful virtual events for young Jewish adults is to provide community and connection before content. We argue that for leaders and other professionals, a similar approach applies.

So much of today’s pandemic challenges are outside of leaders’ lived experience, with a learning curve compounded by a paucity of best practices and continually changing guidelines. Supporting leaders must begin by attending to the human, the need for connection, and the emotional needs of leaders. Attending to the emotional is not a touchy-feely aspiration; stress is real and has a physiological basis. Stress causes the body to release cortisol, which inhibits the brain’s ability to proliferate dendrites and create new circuits. In other words, stress inhibits the brain’s ability to learn. So, to unlock learning, begin by addressing the human elements.

Research on professional learning shows the most powerful professional learning occurs in the context of work itself and solutions come from ongoing access to and informal conversations with peers. Only a peer understands the depth of what it means to stand in those shoes and has the shared language to describe it. Being able to reach out to the right person at the right time can be invaluable. In our experience, leaders are expressing a hunger to speak with each other about how they are handling COVID related challenges. And, thanks to Zoom, Teams, Meet, and more, we have unprecedented opportunities to bring people together.

By bringing people together, we give Aron a space where he feels understood, sees others dealing with similar challenges. His stress levels drop, unlocking his capacity to learn. But from whom? There are no experts on leadership in times of a pandemic. Aron and his peers need to co-create their knowledge together, writing the playbook themselves. Our own experience shows – and research validates – that participants in a well-facilitated networked model of learning can – in close to real-time – identify emerging challenges, deal with complexity, learn from experiments, share resources, create and spread innovation, and move a field forward.

Following, are a few success stories about ways the pandemic is providing new opportunities for organizations and individuals to find peers. We also share tips about how gathering differently can create stronger outcomes.

Find Your People

Example: Prizmah: Center for Jewish Day Schools

When COVID hit, Jewish day school professionals serving in nine different roles – ranging from Jewish studies teachers to school counselors – reached out to Prizmah, the network for Jewish day schools across North America, to support them in convening. Prizmah used their existing infrastructure to form these new online communities, including professionals they had not previously convened, like the gym teachers who were suddenly faced with offering online gym class.

As an organization dedicated to connecting people with peers, experts, and resources, Prizmah already had monthly facilitated peer-to-peer gatherings for heads of school from across North America. At the start of COVID, heads of school requested more frequent time together and shifted to meeting weekly to get the support they needed. The nine new online communities found support through Prizmah, who had the infrastructure and staff in place to transition immediately to gathering more often with more groups. By listening to network members and building on their network of resources, Prizmah was able to serve a timely and critical need.

Networks are a Long Term Strategy

As illustrated by Prizmah, networks are a long term sustainable strategy. As Debra Shaffer Seeman, Prizmah’s Director of Network Weaving describes, “Investing in relationships makes all the difference. During periods when time is of the essence, pre-existing relationships allow for open sharing, trusted feedback, and quick input without the need for formal introductions or starting from scratch. Once a trusting relationship is formed, it is there to be easily activated when the necessity arises.”

Gather Differently

Once you have found your people, we believe the realities of COVID require thinking differently about gathering. The goals of gathering in many professional development contexts have been focused on knowledge transfer, bringing in guest experts, or sharing case studies. We argue that during COVID, professional gatherings should provide space and opportunities for social and emotional support as well as stimulating learning and we provide an illustration and resources below. In addition, with the right facilitation and convening strategies, we see significant upside potential to stimulate innovation and catalyze collective impact.

We understand there is significant resistance to group time and energy focused on the ‘touchy-feely stuff’ of relationship building. Yet, profound learning occurs when professionals feel safe enough to ask questions, reveal their vulnerabilities, and explore what they do not know. Gathering differently means balancing a group’s intellectual growth with growing the relational underpinnings and trust that support network members.

Example: New England Hemophilia Association (NEHA)

Before COVID, NEHA had run in-person sessions for members with a format of the guest expert followed by Q & A. With the start of COVID, Sarah Shinkman, NEHA’s Program Director, realized there was a need for something more and started experimenting with Zoom breakout rooms. Sarah explained, “Breakouts in Zoom let attendees see each other, see facial expressions, and have stronger connections. The discussion becomes more meaningful, intentional, people are inclined to share more about their experience because they feel the energy, emotions, and connections from each other. It allows people to be more vulnerable.” Sarah’s insight and responsiveness increased her members’ learning, as well as their confidence in the support offered by the network.

Gathering Differently Requires Excellent Design and Facilitation

Excellent facilitation is essential for a strong network. Unlike a hierarchy that has a clear chain of command, we believe partnering with a network is best accomplished through facilitation. A facilitative stance allows the creativity and out of the box thinking of a group to emerge.

We recommend conveners build their facilitative muscles by undergoing training and watching master facilitators at work to continuously expand their repertoires. In the example above, COVID motivated a simple tweak in gathering – breakout rooms – that enabled more sparks of connection and intimacy, enriching and deepening network connections thereby creating social and emotional support for participants.

TIP: We recommend systematically using breakout rooms after a presentation to help participants synthesize what they heard, hear other perspectives on the topic, and think about how to apply what they learned to their own experience.

Resources for Gathering Differently

The new zoom client, released in late September, has an option that allows attendees to move across breakout rooms on their own creating many new and exciting formats ranging from a virtual cocktail party (Rae Ringel) to Open Space.

Other resources we have found to be useful in gathering differently include:

- Troika Consulting from Liberating Structures – In quick round-robin “consultations,” individuals ask for help and get advice immediately from two others via peer-to-peer coaching triads. The virtual hack is to turn off your video instead of turning your chair around (Tanja Sarett). [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Upstart’s Guide to Facilitating in the Virtual World is a comprehensive guide focused on tools for meetings of 30 people or less. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Using Jamboard for Network Mapping by June Holley uses Google’s virtual post-it note board, to help members get to know each other and find their common interests. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Virtual Gathering In The Time Of Corona, Priya Parker’s introduction to virtual gathering, includes creative ideas for simulating pre-event mingling with Zoom meetings and other basic concepts. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Engaging People with Lived Experience Toolkit and Facilitating Meetings with People with Lived Experience of Inequity from 100 Million Healthier Lives, hosted by Community Commons. This toolkit aims to create flexible, deeply collaborative strategies for a diverse group, enabling a plurality of voices to be heard and contribute.

Conclusion

This is a time that calls for learning together. After speaking with Naava, Aron reached out to his umbrella organization and reached out to his peer network. When we last spoke with Aron, instead of feeling overwhelmed and isolated, he felt supported, engaging with his network (and other supports) and knowing that his network was there for him.

* Aron’s name has been changed to protect his privacy.

Do you have a story of gathering differently in the pandemic? Learning differently? We want to hear it!

originally published at ejewishphilanthropy.com

About the Authors

Naava Frank (naavalfrank@gmail.com) is Institutional Giving Manager at Honeymoon Israel and leads the Network of Network Leaders – an initiative founded by Cyd Weissman of Reconstructionist Rabbinical College that brings network facilitators together for support and to learn from each other. As Director of Naava Frank LLC/Knowledge Communities, Naava has devoted her career to enabling nonprofit organizations to maximize the outcomes of Communities of Practice. Naava lives in Riverdale, the Bronx, New York.

Ziva Mann is the Director of Learning and Development at Ascent Leadership Networks, where she helps leaders understand their capabilities, and guides development for individuals and organizations. Ziva is also faculty at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement for the 100 Million Healthier Lives initiative (100mlives.org), working with a network of change leaders to improve equity, health, and wellbeing. She is also the director of ZMM Consulting, LLC. Ziva lives in Massachusetts with her husband and sons.

Network Mapping and Analysis : How-to Guide | Societal Platform

October 27, 2020Blog,Network mapping,Network Processes

Societal Platform Thinking emphasises the importance of network effects and facilitating interactions between and within formal and informal networks, involving state (sarkaar), civil society (samaaj) and markets (bazaar), to catalyse large-scale systemic change.

Network mapping and analysis can be a useful way to understand all the interactions happening in the network and the roles different actors play in the network—with respect to a specific Societal Platform mission. The ShikshaLokam example used in this guide, particularly in the network mapping section, gives a sense of how such a mapping exercise can be done for any Societal Platform mission or goal.

The guide is developed to serve as a reference framework and provide processes to help consultants and organisations engage in the network mapping and analysis process. A participatory process of involving all relevant actors across the exercises will be hugely beneficial in developing a holistic network and imagining new possibilities with the output that will come out of the network mapping and analysis process.

Network Mapping and Analysis: how-to guide:

This guide includes 3 documents:

- Report

- This document helps a Societal Platform mission and mission leader to get an understanding of the existing networks and to plan and develop the network, in the context of their mission.

- Presentation

- This presentation is an overview of the contents and processes mentioned in the document.

- Poster

- The poster provides an outline of the summary of the asset.

DOWNLOAD HERE

Originally published HERE at Societal Platform

Societal Platform is a community of curators, catalysts, and network weavers. They pool their individual strengths and channel their collective imagination to enable social change leaders to advance their missions.

Lesson Learned and Launching Pads

October 22, 2020Innovation,Blog

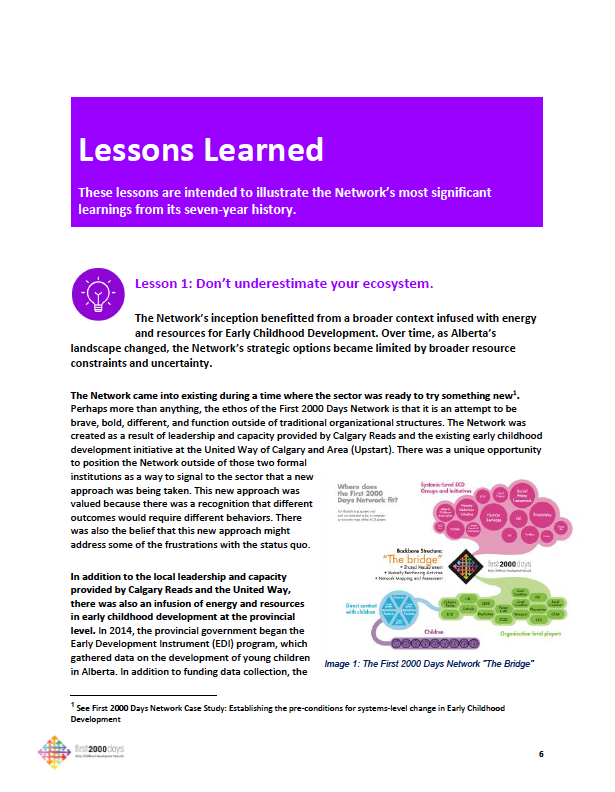

Over the past seven years, the First 2000 Days Network has invested deeply in an adaptive learning approach. This report is a summary of the high-level lessons that came out of the Network’s efforts. Building a high-quality network is a long process and the Network’s success and failures are informative for other collaborative efforts.

The Network was lucky and unique in that it had the time and space to invest in learning from lifelong champions in the sector, leading thinkers on building high quality networks, collective impact, and efforts to support families and children in global contexts. The investment in learning was foundational through the life course of the Network and was one of its greatest assets.

We hope that this report can, alongside many other resources, guide whatever comes out of these turbulent times. There will always be a need to support the youngest members of our communities in a way that acknowledges the complexities – and possibilities – of the systems that impact our everyday lives.

This is one piece of the puzzle.

Click HERE to download the report.

Prepared by Blythe Butler

My work is dedicated to building adaptive capacity in individuals, organizations and communities. My approach is rooted in organizational change, network science, strategy development, evaluation & learning methodologies.

Sami’s practice focuses on developing and implementing learning strategies within networks, collaborative initiatives, government agencies, and non-profit organizations that are striving to make a positive difference in their communities. Since 2013, she has supported them with their evaluation and research needs.

Pathways of Change

An individual approach

Our journey begins with the individual person who has unique experiences, thoughts, and feelings. This uniqueness may sound obvious, but we sometimes take it for granted.

It’s easy to put people into categories when we’re pressed for time or have too many things going on. In a similar way, it’s easy to associate our actions and appearance with the ideals that we grew up with, learned in school, or see in commercials.

Because we’re starting from the individual person, this approach doesn't employ categories or ideals which ignore the intrinsic uniqueness of individuals.

Enhances social change efforts

This vision complements and enhances efforts of social change. The focus on the individual extends the reach of social change.

While social change efforts address issues at the group and systems level, this vision focuses on the unique individual — where issues originate. The combination of groups and individuals provides a more holistic approach to addressing the social problems we experience today.

Social change through what we already know

At one level this vision is a shift of mindsets. It’s a new way of looking at ourselves and a new paradigm of how we interact within ourselves and the world around us.

At another level this vision simply reminds us of what we already know. It’s realizing that we are already at the place we want to be. We just have to act upon it.

This movement of reminding and realizing is small, yet it lays a foundation of social change.

Dissolves the source of racism and discrimination

Seeing our own unique selves helps us understand that categories and ideals don’t apply to humans.

This leads to social change because we no longer categorize individuals or idealize them. It dissolves the source of problems like racism and discrimination before those problems start.

Reduces the source of prejudice and hate crimes

When we realize that our authentic knowledge comes from within us, we understand that others have their own authentic knowledge. Each of us makes lasagna and mixes paints in our own unique way based on our own authentic knowledge.

Our uniqueness extends to our everyday lives. The way we live is different for each one of us, in part because of our own authentic knowledge.

This leads to social change because we no longer expect people to live the same way we do. It reduces problems like prejudice and hate crimes before those problems begin.

Lessens the source of gender and racial inequalities

When we understand that each of us is different, and act on that understanding, then we realize that each person’s way of living is different. Accepting our differences moves us toward treating each other with more respect and kindness.

This leads to social change because we no longer expect people to live the same way we do. It lessens the source of problems like gender and racial inequalities before those problems start.

Shifting toward practice is meaningful

Shifting the vision toward practice is more than an intriguing exercise. This practice has meaning for each one of us.

Let’s be smart about this shift toward practice.

The hardest part of any journey is the first step. Taking small steps can be simple and easy.

Let’s be understanding about this shift toward practice.

We can imagine this practice in different contexts, but it should fit within the space of efforts, projects, and people.

Let’s be empathic about this shift toward practice.

We should be empathic not just to the person next to us, but also to our own selves. We should remind ourselves that we’re not only here to help others in a chaotic world. We should remind ourselves that we’re also here to help the person inside of us. The person who seeks a world where all individuals are unique and valued, in a life that is important and meaningful.

Russell Suereth founded Pathways of Change to promote a social shift where each person's uniqueness is respected and our daily lives are important and meaningful. His focus is how we can create real and lasting change at the intersection of individual and systems transformation. Russell is the author of the McGraw-Hill book Developing Natural Language Interfaces, the lead inventor on two United States patents, the creator and producer of award-winning music, and podcast creator, producer, and host. He is currently in the Critical and Creative Thinking program at the University of Massachusetts in Boston.

Visit our website.

Visit us at Pathways of Change to find out more about our vision of social change, where each person is unique and our everyday lives are important and meaningful.

Contact us today.

To me the important question is, what do we want to create as individuals of social change? The author Robert Fritz has an interesting view of creativity and realizing our vision.

"The inventiveness of the creative process does not come from generating alternatives, but from generating a path from the original concept of what you want to create to the final creation of it in reality" (Fritz, 1984, pp. 38-39).

This path and the activity of realizing is what I want to share with you. Please contact me directly through email at russell@pathwaysofchange.org. I look forward to hearing from you.

Russell Suereth

References

Fritz, R. (1984). The Path of Least Resistance: Learning to Become the Creative Force in Your Own Life. Random House Publishing Group.

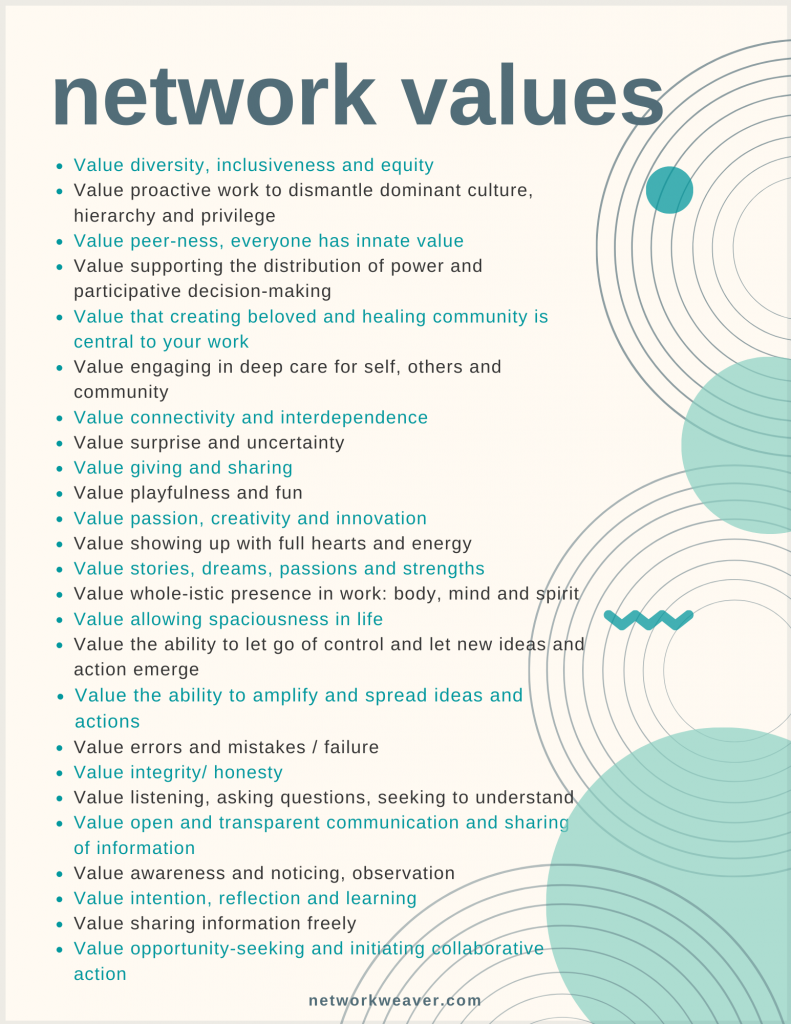

NETWORK VALUES

September 18, 2020Blog,Equity,Dismantle Racism,Reflection and Learning,Network Mindset

Having a group or network take a values survey raises awareness of the values and behaviors that enable networks to be system shifting or transformational.

Network Weaver has published a Network Values Module. Within this module are links to two web-based network values surveys, along with instructions. Also included are printable versions of the network values surveys and a printable flyer of a compiled list of Network Values.

Download the free module HERE

PURPOSE OF NETWORK VALUES SURVEYS

The purpose of having a group or network take a values survey is that it raises awareness of the values and behaviors that enable networks to be system shifting or transformational. It also gives clear information about the specific value areas where they need to work together to help each other shift to more network ways of being. People take the survey, immediately see the aggregated results, and work together to develop strategies for shifting challenge areas.

It’s extremely valuable for groups of networks to take the survey every six months (or even more often at first) so that they can see the progress they have made in shifting to network values and identify areas that still need attention.

There are two values surveys in this module.

- #1 Network Values Checklist

- #2 Network Values Dashboard (for individuals and organizations)

The first one is for individuals. It is used to help individuals identify the areas where they are already behaving from network values. You can have the group aggregate the results of everyone who took the survey so that they can see to what degree they as a group or network have shifted to network values and behaviors.

The second survey has two versions of each question. The first asks the individual about their values. The second asks the individual to rate how their organization ranks in reflecting this value or behavior. Usually the participants will score higher than their organizations. This survey helps people recognize that they cannot simply shift their own values, but need to work with their organizations to shift the entire organizational culture – if they want to be transformative in their impact.

Download the Networks Value Module HERE

SYSTEMS CHANGE & DEEP EQUITY

September 10, 2020Transformation,equitySystems Change,Collaboration,Transformation,Blog

PATHWAYS TOWARD SUSTAINABLE

IMPACT, BEYOND “EUREKA!,”

UNAWARENESS & UNWITTING HARM

An Interview with Sheryl Petty and Mark Leach

Below is the introduction to the full Systems Change & Deep Equity monograph offered by Sheryl Petty of Movement Tapestries and Mark Leach of Change Elemental.

Available for download here at Network Weaver or directly from Change Elemental’s Website.

Change Elemental chose to offer a monograph to share our thoughts on the inseparability of Systems Change and Deep Equity, given our 40 years as an organization in the systems change, capacity building, and social justice fields. (1) We offer this especially given the proliferation of equity awareness and significantly deeper requests for equity support across the organizational development and movement network fields in the last few years. This expansion in requests for deep, transformational equity support has grown dramatically since the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Now, many more social change organizations and philanthropic institutions are working to deepen their knowledge and capacity around Systems Change and Deep Equity. In our opinion, the combination of these two fields is pivotal and likely the work to do for the next phase of our human evolution if we are to become the societies we hope for in our deepest hearts and visions for just and healthy communities.

The co-authors of this article have 65 years of combined experience in systems change, equity, and organizational transformation. We have worked together on a number of projects for nearly 8 years, sometimes separately and, at times, together in local, national, and international spaces. We have worked across foundations, non-profits, medium-to-large school systems and universities as well as with individuals, institutions, and networks to support leaders, change agents, and groups to deepen their capacity to realize the full potential of their missions and collective dreams. We have observed over the last decade or so in the field of organizational development, the more popular advent of “Systems Change” as a domain of effort that can lead to more comprehensive, lasting, and effective transformation for institutions, communities, neighborhoods, and groups.

Yet, our observation is also that these approaches to “complex systems” are new to some and not so new to others. Here enters “equity.” We have written elsewhere on the dimensions of equity, and refer readers to those pieces. (2) Others of our colleagues have also written extensively across the fields of social justice, organizational transformation, network development, and movement building. (3)

Our purpose in this article is to dispel mythology and to illuminate essential dimensions of approaches to Systems Change intimately connected with Deep Equity. Our perspectives and our experience have shown us that the two are inseparable if they are to be pursued at depth. The degree of healing needed in our world, and in our collective institutions and communities, requires nothing less than depth from us at this time (if less comprehensive approaches were ever appropriate).

We indicate in this monograph what, from our perspective, are the most salient aspects of approaches to Systems Change and Deep Equity combined that can lead and, in our experience, have led to the most profound changes in organizations, local, national, and global communities, networks, and movement building efforts. (We also refer readers to Change Elemental and Building Movement Project’s 2018 webinar on Systems Change and Equity for further grounding in our approaches. (4) )

As we have stated, nothing less than the robustness of complex Systems Change approaches are necessary to solve some of the most intractable situations we are and have been facing for quite some time—socially, environmentally, and economically, in terms of the overall health and well-being of individuals and communities, nationally and globally. We have grown as a species in our ability to be aware of the interconnectedness between so many of our issues and circumstances; this insight is a gift. We are now challenged to take that growth and insight, and apply it at depth with particular attention to our areas of unawareness—i.e., the places we have been ignoring for centuries. It is to these areas that Deep Equity speaks. In fact, Deep Equity, by its very nature, is complex Systems Change.

To put a finer point on these statements: Systems Change pursued without Deep Equity is, in our experience, dangerous and can cause harm, and in fact leaves some of the critical elements of systems unchanged. And “equity” pursued without “Systems Change” is not “deep” nor comprehensive at the level of effectiveness currently needed.

Both need each other. The challenge in effectively combining these domains of practice is that often many systems change actors—particularly those with access to publishing, funding, and other critical resources to achieve depth and scale—do not seem to understand nor are they embedding Deep Equity into their work. Or when “equity” is addressed, it is piecemeal, seems an afterthought, and/or is shallow. Actors pursuing and advancing critically needed systems change efforts often bring limited awareness to address or adequately embed equity. This is the wound we must heal.

We have observed too many times systems change efforts pursued to the neglect of equity, or Deep Equity, despite living in a period where information about equity (and Deep Equity, in particular) is proliferating at an unprecedented rate. Gone are the times when any of us could say, “I couldn’t find any information on it,” “I didn’t know anyone,” or “I didn’t know better.”

We owe it to ourselves and to each other to confront our old habits that are preventing us from creating the most robust, healing, catalytic, life-affirming, and transformative solutions we can develop, and that are desperately needed. Pursuing Deep Equity and Systems Change will require us to squarely address issues of power, privilege, places of unawareness, and the meaning of “depth” in approaches to equity and systems change. It will take bravery and courage, finding out how deep we are really willing to go to help heal and transform this world, committing to the depth that we discover in our exploration, and partnering and complementing each other in ways that may be heretofore unprecedented. (5) (We also refer the reader to a previously published piece from one of the authors on the relationship between these two themes plus “inner work:” “Waking Up To All of Ourselves: Inner Work, Social Justice & Systems Change.” (6) )

This monograph is structured as an interview of Sheryl Petty conducted by Mark Leach, but it is ultimately a dialogue between two long-term Systems Change and Equity actors.

One of us is a soon-to-be middle-aged cisgendered, (7) queer/pansexual, Black woman from Detroit, whose professional career in social justice and Systems Change began in Oakland, CA in educational systems and nonprofits, and branched out into capacity building and systems change with school systems, nonprofits, and philanthropic institutions around the country over the last 25 years. She also has a nearly 25-year inner work practice in African-based and Tibetan Buddhist traditions, in both of which she is ordained and teaches.

The other of us is a well-past middle-aged, cisgendered, white man from Long Island, New York. Based on early experiences in some of the world’s most economically poor countries, he has spent his life trying to understand who gets what, and why, and working with people, organizations, and networks across big differences in identity, wealth, and worldview to tackle big, messy problems of systemic inequity.

Systems Change & Deep Equity is available for download here at Network Weaver or directly from Change Elemental’s Website.

1. Change Elemental was formerly known as Management Assistance Group (MAG). We changed our name in April 2019.

2. For example: Petty, Sheryl. Seeing, Reckoning and Acting: A Practice Toward Deep Equity. Change Elemental, 2016. https://changeelemental.org/resources/seeing-reckoning-acting-a-practice-toward-deep-equity/ ; and Petty, Sheryl and Amy B. Dean. Pursuing Deep Equity. Nonprofit Quarterly, 2017. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/five-elements-of-a-thriving-justice-ecosystem-pursuing-deep-equity/

3. Please see more resources listed in the appendix.

4. Systems Change with an Equity Lens: Community Interventions that Shift Power and Center Race. Change Elemental and Building Movement Project, 2018. https://changeelemental.org/resources/systems-change-with-an-equity-lens-community-interventions-that-shift-power-and-center-race/

5. Petty, Sheryl. “Introduction.” Equity-Centered Capacity Building: Essential Approaches for Excellence and Sustainable School System Transformation. Equity-Centered Capacity Building Network (ECCBN), 2016. https://capacitybuildingnetwork.org/intro/

6. Petty, Sheryl. “Waking Up All Of Ourselves: Inner Work, Social Justice, & Systems Change.” Initiative for Contemplation, Equity, and Action Journal. Vol. 1, No. 1, pages 1-14, 2017. http://www.contemplativemind.org/files/ICEA_vol1_2017.pdf

7. Cisgender is a term used to describe people who identify with the gender assigned them at birth. Source: Words Matter: Gender Justice Toolkit. National Black Justice Coalition. https://www.arcusfoundation.

Featured Photo by Jaccob McKay on Unsplash