Leadership and Community in a Time of Transition

April 6, 2021Blog,Network Leadership,Dismantle Racism,Liberating Structues

In communal transformation, leadership is about intention, convening, valuing relatedness, and presenting choices. It is not a personality characteristic or a matter of style, and therefore it requires nothing more than what all of us already have. This means we can stop looking for leadership as though it were scarce or lost, or it had to be trained into us by experts. If our traditional form of leadership has been studied for so long, written about with such admiration, defined by so many, worshipped by so few, and the cause of so much disappointment, maybe doing more of all that is not productive. The search for great leadership is a prime example of how we too often take something that does not work and try harder at it.

Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging

As a white man born into a well-off and well-educated family in the US, the idea that I might step into leadership was part of my conditioning. And as someone who has chosen work that involves issues of justice, equity, and inclusion, I find myself challenged to re-evaluate the very definition of leadership. In this, I have found two books to be particularly helpful. Reading Peter Block’s Community: The Structure of Belonging in 2010, I was struck by his declaration that “leadership is convening,” and by the concrete guidance he provides for living into that story. Some years later, I was further inspired by Frederic Laloux’s description in Reinventing Organizations of a new paradigm for governance, his addressing of questions related to hierarchies and self-organizing, and his vision for what might be possible as we continue to evolve our capacities for new forms of organizing. Both authors start from the premise that our conception of leadership in the dominant Western culture is failing us, opening the way to new approaches based on “power with” rather than “power over.”

I was brought up within that dominant culture as one of its most privileged members, and was taught to excel in things like critical analysis and debate. Then in 2010, I found myself called into work inspired by a new possibility that I suddenly recognized: we could make powerful use of our new virtual capacities to convene large groups of people by engaging them in generative dialogue about systemic transformation. I found that my old training did not serve me and was in fact a handicap in many respects. At the same time, I discovered that I had gifts for creating and holding hospitable space, listening deeply, and making meaning out of the diversity of opinions, beliefs, and worldviews that were being expressed in the conversations I helped convene. Block’s work offered both a powerful validation of this new direction and a road map for the journey.

Around the same time that I was reading Community, I had the delightful experience of shifting my story about myself. I had worked with a professional career consultant a few years earlier and had tested as an introvert (INFJ) on the Myers-Briggs personality inventory. Then one day while driving home and mentally preparing for a World Cafe conversation I was about to host online, it struck me that the excited energy I was feeling was characteristic of extroverts. So I immediately called my friend David, a Myers-Briggs maven, and asked him to look up the characteristics of the ENFJ personality. The answer? That people like me are leaders of groups, and that others are drawn to participate in those groups not because of efforts we make to persuade them that they should do so, but simply because of the way we show up. In Block’s words, this is “invitation as a way of being,” where the artist replaces the economist/salesman.

As I reflected on why I might have scored as an introvert, it occurred to me that I had exiled my gifts as a convener of hospitable space. My explanation for having done so was that, throughout my early adulthood, my efforts to show up as a whole person were not well received. So I told myself the story that I preferred my own company and a small set of close relationships, and that being in groups was a challenge for me because of my nature. Accordingly I made my professional world a small one, holding back on what I felt called to most deeply. Reflecting on this anew, it occurred to me that I had intuitively sensed the bankruptcy of the dominant paradigms through which I had been told I was supposed to engage with the world, and that the painful experiences in my work were the result of my rebellion against operating in that context. The discovery of this new way of showing up--as a convener of groups, in service to movements for transformational change-- was utterly liberating.

The other inspiration I drew from Block was the idea that community is required for transformation. It is not enough for us to work on ourselves in isolation. As Thich Nhat Hanh has famously said, “the next Buddha may be a sangha.” And so I embraced the creation of community as a core purpose of my work. I came to see the emergence of social fabric made up of many interwoven relationships as being the most important outcome in any engagement, over and above the conversational content or action planning that often provides the explicit context for a gathering.

The places where we live are failing to provide a strong sense of community for many of us. Other traditional markers such as nationality, ethnicity, gender, political ideologies, extended family structures, etc. also often do not seem sufficient or lack resonance. As a result, we are witnessing the increasing fragmentation of identity, accompanied by a yearning for belonging and connection to replace what we have lost. The dangers of this phenomenon are apparent all around us, most prominently in the political realm, as a product of the broader challenge of simply identifying a shared reality. As we all struggle with the fact that conventional wisdom has shown itself to be incomplete, flawed, and sometimes false, many are choosing to embrace conspiracy theories--a phenomenon that I believe to be toxic. Yet I also see a great opportunity in this unraveling--a chance for humanity to go through a kind of reweaving (or re-wilding) that builds upon what was good and important about our previous stories and forms of identity, yet also transcends the limits they carried with them.

As we co-create new forms of community, we get to try out identities that connect us directly to our gifts. Anthropologists have determined that the natural size for a tribal unit is a little less than 160 people, and that the “gift economy” was the original form of organization that we employed in such groups. I love to imagine what a group that size can do today with the power of our new technologies, if it succeeds in fully bringing forth the gifts of its members and releasing them into the world. And what might be possible if these “tribal groups” learned to connect and collaborate with one another, based on natural alignments in purpose and values? And then what if we learned to do this in a way that reconnected us to the earth as a whole, by linking together our care for each of the places where our feet touch the ground?

This vision of transformational communities requires a good deal of coordination, collaboration, and co-creation both within and among groups. So it is not surprising that the crucial need for wise and effective governance has emerged in my work time and time again. Tom Atlee, my first mentor in the convening work I began in 2010, introduced me to the concept of collective intelligence and to a wide variety of processes that have been developed for tapping into it, including many that relate to governance and decision-making. His new Wise Democracy Pattern Language is a wonderful resource, as is the Co-intelligence Institute website he curates.

The need for governance structures became more tangible for me when I co-launched Occupy Cafe and was exposed to consensus decision-making and Sociocracy. Not long after that, I became part of the core team for the Great Work Cultures initiative and was also introduced to the Future of Work movement, both of which focused on new paradigm approaches to decision-making and sharing power in the workplace. Another influence was the concept from The Circle Way of “a leader in every chair.” And the related idea that movements need to be “leaderful” rather than “leaderless” came from Peggy Holman, whose book Engaging Emergence also taught me practical and inspiring approaches to convening. Then in 2014 I read Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations, which seemed to pull it all together.

Like Block, Laloux presents models for organizing ourselves using “power with” rather than “power over.” In his synthesis based on the study of a wide variety of organizations, he identifies three key innovations: evolutionary purpose, self-organizing, and the welcoming of our whole selves into the spaces where we work. He gives examples of each of these patterns happening in a number of organizations, while also stating that he has yet to see any instance where all three are present in a single one. Since he wrote his book, many people--myself included-- have been inspired by his observations (and those of the many others working on similar visions of “next stage” organizations) to attempt to co-create initiatives that have all three of these elements in their DNA.

One of the interesting patterns I've observed in groups that take up this challenge has to do with hierarchies. Because our old models have failed us so dramatically in so many respects, there is now a deep mistrust of leadership. And because so many voices have been marginalized for so long, there is a need for them to now be heard. How we learn from these experiences in order to create spaces where we thrive can be a tricky thing.

I remember vividly my visit to the Occupy Wall Street encampment in New York City in 2011. I was particularly struck by the general assembly I witnessed that day. There was a problem to deal with: a giant pile of dirty, wet laundry had accumulated as a result of several days of rain. It was beginning to mildew. Someone had already secured a truck and located a laundromat uptown that would welcome them. All that remained was for the group to decide to allocate money for the laundry machines. There were easily 150 people participating in that deliberation. It took over an hour (using the famed “people’s mic”) to hear everyone who wished to speak and to decide that yes, the money should be released so that the laundry could get done. While many might have seen this as something less than good governance, I chose to interpret it as a kind of communal poetry!

It is crucial that we create spaces for collective expression that allow all voices to be heard. Peter Block gives us one model for doing so in a way that weaves community and brings forth our gifts. His approach creates a context of relatedness, trust, commitment, and the safety to dissent. These are crucial precursors to sharing power well, but we also need structures and processes designed to support us in making decisions together in a good way. A key pattern for doing this, as Laloux found in his research, is the empowerment of small groups closest to the work that needs to be done as the vehicle through which authority is allocated. As Block also declares: “the small group is the unit of transformation.”

When needed, small groups can seek input from the whole community or organization, and can also reach out beyond it to all stakeholders, if desired. We have lots of great methods for this kind of "advice process," not to mention talented facilitators who love this kind of work. But it still makes sense in most cases for a small group--people connected to the needs being addressed and the consequences of their choices-- to process that broader input, make an appropriate decision, and then stay engaged and agile in order to respond to what happens as a result. Sociocracy works in this way, and I am very drawn to that methodology, although a full implementation of all its elements may not be the right answer in many cases. Indeed, I don't believe there is a one-size-fits-all solution, and I think that we are still very much in the beginning stages of figuring out how to do this well. This is especially true to the extent that we wish to transcend the organization as the core unit through which work must be done, returning to communities as the way to meet many more (and perhaps even most) of our needs.

The context in which these questions about leadership and community have the most meaning for me is the possibility of near-term civilizational collapse. Though Jem Bendell has become perhaps its most prominent voice today, Meg Wheatley was the thought leader I first paid attention to who was preaching this gospel. After many years of working to support the emergence of a new paradigm for humanity based on the idea that “whatever the problem, community is the answer,” Wheatley had a change of heart, giving up on the idea that we could still “save the world.” In her 2012 book So Far from Home and the subsequent Who Do We Choose to Be? she painted a stark picture of despair among many who, like her, had worked for decades to bring forth a world that works for all beings. Now she spoke instead of the need for leaders to create “islands of sanity” amidst the sea of collapse.

Is Wheatley right? Joanna Macy, the contemporary of hers who popularized the term “the Great Turning” to encompass the magnitude of the civilizational shift they and others were imagining, says that we still don't know whether it is too late for us to midwife that better world or not. I find her view to be compelling as well. This brings me back to Block, who emphasizes that the story we choose to tell ourselves is just that: a story and a choice. And that the choice we make has payoffs and costs.

And so I will close with a story I choose to tell myself. Holding onto it gives me the payoff of validating the community weaving work I feel called to do, and my sense of having found a good way to be a leader. It therefore helps me to minimize the guilt I hold onto for living a privileged life, including not doing more to dismantle the systems of oppression I benefit from, and choosing to have an environmental footprint that is way bigger than my personal fair share.

What are some of the costs of my attachment to the story? One is that I may not be paying attention to other possibilities for making use of my gifts. Another is that my sense of self worth and identity is dependent on outcomes I often cannot see and must take on faith. A third might be that I have fooled myself into believing that I am practicing “power with” when in fact I am perpetuating the old patterns of “power over.” Furthermore, this story leaves me open to the criticism that I am a “virtue signalling” hypocrite because, while I claim to be a stand for the need to transform our ways of doing things so that we reweave rather than unravel our environmental, social, and spiritual life support systems, I am choosing a life of privilege that contributes to that very unraveling.

For now, knowing all that, I am sticking with the story...

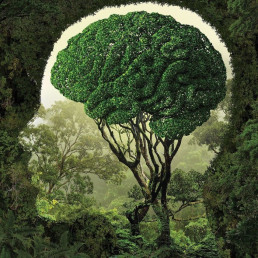

There may not be much difference between the work of creating islands of sanity and of reweaving the whole world. It might “simply” be a matter of tens of thousands of transformationally empowered communities, each doing powerful work in their own local domains (be they place-based or virtual) while also supporting one another to bring forth a global shift. For all we know, just as the mycelial mat is hidden from our view and has only recently come to define our basic understanding of how a forest works, a sufficiently dense weaving of relationships, flows of information and resources, and connections to other parts of the transformational ecosystem might already be underway such that tens of thousands of these communities are springing up around the globe, mushroom-like, in order to nourish us, transform our collective consciousness, and cast billions of potent spores to the winds of change.

*Published in the Sharing Corn Journal, Volume 2, available from Joy Generation in print form here and in digital form via Amazon here.

featured image found at WSJ.com

Ben Roberts is a systemic change agent and“process artist,” working in service to what Joanna Macy and others have called "The Great Turning." Inspired since 2010 by the internet’s largely untapped power to convene and support new modalities for participatory dialogue, he has been a pioneer in bringing large group conversational processes into the virtual realm via platforms such as Zoom and Slack, and in blending and creating synergies between virtual and in-person engagement.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

From Nature’s Mutualistic Networks to More Resilient Human Networks

March 29, 2021Network Weaving,The Big Picture,Blog

We have been taught to live in a competitive, survival-of-the-fittest world. But what if this has been wrong? What if the natural world, and the humans in it, are much more cooperative than competitive?

The idea of the survival of the fittest originated in Darwin’s Origin of Species, and his theory of natural selection. Sure, natural selection does have a role to play in evolution, but it might not be as important as we had previously thought. In fact, some scientists assign it a weight of just 1 out of 10 concerning the evolution of certain processes, such as the evolution of the anatomy of species[i]. Other scientists suggest that evolution should not be considered in terms of species as separate from its environment, but at the level of the system itself (species + environment). Looking at it from this perspective, they maintain, is much simpler and governed by a much smaller set of laws, than analyzing the evolution of elements by themselves[ii].

We can find examples of mutualism and cooperation all over the natural world, from pollinators and plants, to animals and the microbes living in their guts. And in many cases this cooperation is not merely optional, but essential to life itself. Certain plants will not grow in soils where you cannot find a specific type of fungi, since they need to form a relationship with it in order to survive. Lichens are an association between a bacterium and a fungus. They are an organism that is an association of two different life forms, contradictory as the notion may seem. Trees communicate with each other through a network of mycorrhizae, a fungal structure invisible to the naked eye that connects their roots, transporting nourishment, messages and even teachings (yes, plants have cultural transmission and are able to learn from their neighbors)[iii].

And the human species is no exception. We have more bacteria living in our gut than we have cells in our bodies, and they influence our health, our moods and even our behaviors[iv]. Without them, we cannot survive. (Not to mention the fungi that live basically everywhere and the microscopic mites on our skin.) We are not just a single organism; we are a small cosmos of organisms. And like all other species, we are not meant to just compete, but to cooperate harmoniously with those around us.

What is conspicuous about cooperative interactions in the natural world is that they happen in networks. This a very familiar word in the human lexicon, since we network for just about anything: for business, for trade, for information exchange. What can we learn from these well-functioning natural cooperative networks that we can apply to our human ones, so that they are more resilient?

First of all, if we take a look at mycorrhizal networks in old-growth fir forests[v], we find that young saplings are established within the networks of veteran trees. Usually, the larger the trees (and the more resources they have), the more well-connected they are within the forest network. This highlights the importance of large mature trees in the architecture of the network, which have long life-histories of connection. Greater establishment of young saplings have also been shown when they are linked into the mycorrhizal network of larger trees. The lessons to learn from this are quite simple: if you have more resources, share them, and you will help others flourish. Also, we need multigenerational human networks: elders have a lot of wisdom to impart, and if youngsters are connected to them to “absorb” it, they are more likely to thrive.

The forest networks also have what we call small-world properties, meaning that individuals are closely knit together, and that you do not have to go through many to get from any one individual to another. Simple enough as well, right? Do not isolate yourself, if you connect and collaborate with others, you are also more likely to thrive in your community.

Forest network symbiosis is not just an affair between two or more organisms, but a complex assemblage of fungal and plant individuals that spans multiple generations. In them, fungus species form “living links” connecting trees and allowing them to communicate and exchange resources, and benefitting from the exchange as well. In our networks, human connections do not have to be strictly restricted to flows of information or products, they can be other people (facilitators, teachers, networkers), living links that enable effective exchange of any kind between other people or groups.

Last but not least, these networks are robust to perturbations, but fragile to the targeted removal of the “hubs”, large mature trees. If elders are left out or removed from contributing, the whole ecosystem is more likely to collapse.

So far, we have been looking at relatively simple networks, connecting individuals of a few species only, and belonging to the same forest “group”. Now let’s take it a step further and take a look at networks that involve far larger numbers of species interacting. And at the same time make an analogy with different “species” of organizations trying to cooperate.

There are several types of networks in nature, and they are of two main types: antagonistic (e.g: food webs, parasitism) and mutualistic (e.g: pollination, seed dispersal). A study by Thébault and Fontaine[vi]analyzed several characteristics of both types of networks, focusing on pollination (mutualism) and food webs (antagonism), to find out what made them more persistent and resilient. They found out that the two types of networks behaved quite differently.

While antagonistic networks benefit from being modular (having subgroups that interact heavily amongst themselves and very little with other groups – does that sound familiar?), the cooperative mutualistic networks that we are interested in were strengthened by a nested structure. This means that there are a lot of “specialists” in the network, interacting with subsets of the group that “generalists” interact with. At an organizational level, “generalists” are larger organizations that have several areas and a wide range of action, such as groups focusing on governance and policy, and can interact with many other smaller, grassroots “specialists” focusing on one or two areas of action. How do we ensure the nested structure in a human network? We make sure that there are no local groups that are isolated from the world at large and from larger spheres of power. The smaller grassroots organizations and groups can (and should!) cooperate with each other at a local level, but not without being connected to larger organizations that ensure that they have a voice at a regional, national or global level.

Another study[viii] provides even more lessons to be learned from nestedness: it not only helps to reduce competition and increase the number of coexisting species, but a nested structure like this is likely to arise by itself, as long as new species enter the community at the places where they have the least competitive load. When a new group wants to cooperate, welcome it in the place where it is most needed, where the skills and value it provides are most lacking, and take the best advantage of the complementarity!

Mutualistic networks tend to have one other characteristic in common, which is related to nestedness: they are asymmetric. There are a few “generalists” and a whole lot of “specialists”[ix]. The generalists interact with each other, but also with the specialists. A lot of grassroots activity is good: but so is getting the word out there about your work and spreading local solutions to the global level—”Think Global, Act Local”.

The final two things that increase persistence and resilience of networks are two very simple ones: high diversity and high connectance. Diversity is self-explanatory, and quite obvious. High connectance means that a high percentage of the possible links are materialized, so also at this level, connect and collaborate as much as you can (within reason), and the benefit for all will be increased.

And here is a bonus lesson: a study by Evans et al.[x] that analyzed the interconnectivity of networks on a British farm reached a very interesting conclusion. Two habitats that were not very representative in terms of area were disproportionately important. This gives us a clue that there may be groups out there with skills and areas of action that still tend to be overlooked at the grassroots and even the governance level (tipping my hat to the ethical technology and governance folks), but whose work others will rely immensely upon to be able to keep the integrity of the network.

But this is not the end of it: stay tuned for the multilayer nature of ecological networks and how to apply its lessons to community organizing!

[i] Lewin, Roger (1993) Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos. Phoenix, Orion Books, London

[ii] Lotka, Alfred (1925) The Elements of Physical Biology. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore

[iii] Simmard, S. W. (2018) Mycorrhizal Networks Facilitate Tree Communication, Learning, and Memory. In: Memory and Learning in Plants. Springer International Publishing, AG

[iv] Gilbert, S. F., Sapp, J. & Tauber, A. I. (2012). A Symbiotic View Of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals. Quarterly Review Of Biology 87(4): 325-341

[v] Beiler, K. J. et al. (2010) Architecture of the wood-wide web: Rhizopogon spp. genets link multiple Douglas-fir cohorts. New Phytologist 185: 543–553

[vi] Thébault, E. & Fontaine, C. (2010) Stability of Ecological Communities and the Architecture of Mutualistic and Trophic Networks. Science 329: 853-856

[vii] Palazzi, M. J. et al. (2019) Online division of labour: emergent structures in Open Source Software. Scientific Reports 9(1): 1-11

[viii] Bastolla, U. et al. (2009) The architecture of mutualistic networks minimizes competition and increases biodiversity. Nature 458: 1018-1020

[ix] Bacompte, J. & Jordano, P. (2007) Plant-Animal Mutualistic Networks: The Architecture of Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 38: 567–93

[x] Evans, D. M., Pocock, M. O. J. & Memmott, J. (2013) The robustness of a network of ecological networks to habitat loss. Ecology Letters 16(7): 844-852

Originally published at Systems Change Alliance

Top Photo by veeterzy

Carolina Carvalho is a network ecologist from Portugal who researches the interconnectedness of living beings and how we might apply this knowledge to help the human species live harmoniously within the web of life.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Funding Successful Collaborations

March 22, 2021Blog,Network Leadership,Transformation

Professor Wei-Skillern’s decade of research on successful nonprofit collaborations highlights key success factors that closely align with the behavioral changes required for collective impact initiatives to succeed.

In studying successful nonprofit networks, I have found that there are four key operating principles that are critical to collaboration success. These soft skills are the ‘secret sauce’ that differentiates mediocre collaborations from those that achieve transformational change. Surprisingly, the operating principles of funders who have successfully supported networks differ dramatically from common practice in the philanthropic sector.

- Mission not Organization – The Energy Foundation was founded in 1991 as a collaboration among Rockefeller, Pew and McArthur Foundations. With a $100 million commitment over 10 years, the founding donors provided patient capital, agreed that EF should be governed by an expert board rather than large donors, and encouraged the founding executives to be entrepreneurial and let the work of the foundation speak for itself (and to other potential donors) rather than get caught up in building the organization’s infrastructure. Their foresight enabled EF to catalyze the growth of energy philanthropy such that billions are now being committed to the field worldwide, though EF’s own budget has remained relatively modest, amounting to $100 million annually. EF’s goal has always been leveraged impact, not organizational scale. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Trust not Control - EF makes grants to regional groups that carry out energy policy work, then helps them coordinate so they can learn and adapt. Sometimes, EF grants to coalitions of nonprofits which are then able to regrant the funding according to how the local nonprofit leaders think the resources can best be utilized across the coalition. EF president, Eric Heitz describes the foundation’s operating philosophy as ‘service to the field.’ He notes, “We believe that people who are closer to the challenges are often in a better position to make the strategic call.” This is the ultimate in unrestricted funding--allowing the grantee full flexibility to use the funds not only internally, but also through its peers.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Humility not Brand - The Energy Foundation actively seeks to give credit to grantees, instead of trying to take the credit for itself. Indeed, I commonly refer to EF as the biggest foundation you’ve never heard of. It has been tremendously skilled at building the broader field of energy philanthropy yet it is little known. Its track record of success was instrumental in attracting multibillion dollar commitments to catalyze a network of similar foundations globally (see www.ClimateWorks.org). To get work done effectively through a network, participants need to build a reputation for making others look good rather than building a brand for its own sake.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Node not Hub - Although EF has no endowment and must fundraise annually for its own operations, it routinely suggests that donors give directly to others in the field if it is not able to add value. Furthermore, EF routinely invests resources toward field building without an expectation of a direct benefit. For example, EF has lent its executive staff for months at a time to peer organizations to develop capacity for working through networks among their counterparts globally. Eric Heitz will often give presentations to educate other donors to give to the energy field, even if funding for EF is not forthcoming. The goal should be to grow the ‘market’ rather than to to be the market leader.

While there are untold numbers of funders who promote collaboration among their grantees, the number of donors who live and breathe these principles in practice and as expectations among their grantees is rather small. If funders really expect to see more collaborative behavior in the field, a good place to start might be with themselves.

originally published at FSG.org

Four Network Principles For Collaboration Success

How are some collaborations able to achieve spectacular results while others fail spectacularly? This article introduces four key operating principles that build a culture for collaboration success.

About Jane Wei-Skillern: Jane Wei-Skillern is an associate adjunct faculty member at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business and a Lecturer at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business where she teaches social entrepreneurship and studies leadership and management of social enterprises. She has examined the topics of nonprofit growth and management of multi-site nonprofits, and for nearly a decade, has been focused on nonprofit networks. Her research on nonprofit networks examines how nonprofit leaders that focus less on building their own institutions and instead invest to build strategic networks beyond their organizational boundaries, can achieve dramatic gains in mission impact with the same or fewer resources.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

“Lean Weaving”: Creating Networks for a Future of Resilience and Regeneration

March 16, 2021Network Weaving,The Big Picture,Blog

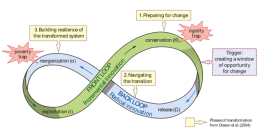

I’m fInishing up David Fleming’s book Surviving the Future, and buzzing with ideas and questions about the role of networks, network weaving and energy network science in these times of “systemic release” (see the adaptive cycle below, and more about the cycle here).

Fleming’s book, a curated collection of essays from the heftier Lean Logic, offers some compelling thinking about the trajectory of globalized and national economies – at best de-coupling, de-growth, and regeneration, and at worst catastrophic collapse – and the ways in which intentional and more localized culture building and reclamation as well as capacity conservation, development and management, might steer communities to healthier and more whole places post-market economy.

One of my favorite quotes from Fleming is that large-scale problems do not require large scale solutions; they require small-scale solutions within a large scale framework. That resonated immediately, even if I didn’t know exactly what he meant when I first read it. Re-reading more carefully, I hear Fleming making the argument that to take on systemic breakdown at scale is a fool’s errand – too massive, too slow, too much rigidity to deal with, too much potential conflict, too abstracted from real places and people.

Instead what is required is more nimble small-scale solutions happening iteratively and quickly (relative to how slow things move at larger levels). This suggests that action for resilience must happen at more local and regional levels, connecting diverse players in place, helping to encourage more robust exchanges of all kinds (including multiple “currencies”) and culture building. David Fleming offers the following definition of the lean economy (as opposed to the taut perpetual growth economy): “an economy held together by richly-developed social capital and culture, and organized around the rediscovery of community.” How might we weave that fabric even as others unravel?

Lean (network) weaving (a new term?) would focus on helping to create more intricate, high quality/high trust and diverse connections as well as facilitating robust, nourishing flows in tighter and more grounded cycles and systems. Part of the lean weaving would entail ensuring that smaller systems remain alert, quick and flexible so as to experiment, learn and adapt. And it would also maintain connection and communication between these smaller systems/clusters (Fleming’s “larger framework”), to facilitate learning and feedback of various kinds between them (not unlike proposed bioregional learning centers).

“The more flexible the sub-systems, the longer the expected life of the system as a whole.”

David Fleming

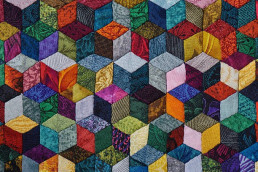

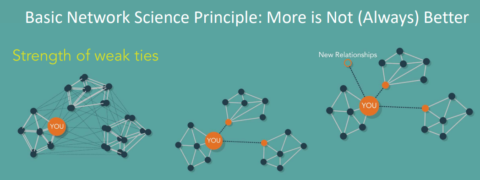

This idea of “lean weaving” also brings to mind the wisdom of network science as taught by Danielle Varda and colleagues at Visible Networks Lab. They make the point that when it comes to creating strong (resilient and regenerative) networks, more can be less in terms of the connections we have. Connectivity, like so much else in our mainstream economy and culture, can be ruled by a relentless growth imperative that is not strategic or sustainable and can cheat us of quality in favor of quantity.

More connections require more energy to manage, meaning there may ultimately be fewer substantive ties if we are spread too thin. Instead, the invitation is to think about how we mindfully maintain a certain number of manageable and enriching strong and weak ties, and think in terms of “structural holes.” For more on this network science view, visit this VNL blog post “We want to let you in on a network science secret – better networking is less networking.”

The COVID19 pandemic along with other mounting challenges may already be presenting the mandate and opportunity to get more keen and lean in our network thinking and weaving, not simply in the spirit of austerity and regression, but to cut an evolutionary path of resilience and regeneration (renewal). Network weavers of all kinds, what are you seeing and doing in this respect?

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate at the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC). Much of his work entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food, education, public health, and economic systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

This is How #WeGovern

March 5, 2021Blog,Equity,Dismantle Racism

Last year, we witnessed the near collapse of our collective systems—the systems that should be sustaining us when we need them most.

And the truth is, they’ve been failing us for generations. Today, amid a global pandemic, sustained violence against Black lives, brazen attacks by white supremacists, climate catastrophe, and pervasive economic injustice--we can see what Black and Indigenous folx have been saying for generations: these systems were not designed for us.

It is time they were.

We Govern is a roadmap for that creation. This foundational set of agreements were written by a group of predominantly Black, Indigenous, people of color across the US, to guide how we make the decisions that impact all of us--including how we choose to live together, use our resources, and build systems rooted in radical care.

It is an invitation to redefine governance.

Governance is the process by which we determine the norms and rules that guide everyday life and behavior, and we—all of us—have a role in it. Whether it’s through our personal lives as parents, friends, neighbors, caregivers, and stewards; or in our work as leaders and decision-makers—the choices we make each day determine our emergent future.

As our FAQ page says, “Whether deciding if it is worth it to struggle with a kiddo to eat broccoli, facilitating a healing conversation among friends, or creating a spending plan for clean energy in your town, the act of making choices for our collective wellbeing is governance.”

Governance is about making decisions together—at small and large scales—about the things that matter to us and impact our lives.

Today, together, we envision a more just, harmonious, and thriving future that refuses to leave anyone behind. We envision a world where we tend to ourselves and each other knowing that the choices we make each day add up to the world we’re building. We imagine systems of radical care in keeping with our sacred responsibility to care for future generations and the earth we share. The world we want is rooted in mutual care, deep relationship, dignity, and safety — for ourselves, for each other, and for the natural world.

Now, in the early part of 2021, we find ourselves still deep in a pandemic, clambering to stabilize the harms of last year, as we continue moving toward a still uncertain future. In this moment, a vision of another world is more urgent — and more possible — than ever.

By planting the seeds of commitment to collective care, we can create the world we want through the choices we make. WeGovern is an invitation to align our actions with our values—to commit to the foundational agreements we need in order to carve a path toward what’s possible.

The world we want — a world where all beings can thrive — begins with each of us. And it can start now.

To be counted among those who are embracing the sacred responsibility to take action and care for our collective wellbeing, sign on here.

Access the WeGovern Media Toolkit HERE or visit WE-Govern.org directly.

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources? DONATE HERE to assist us in continuing the shared vision & collaborative campaign for equity, justice, & transformation.

Can problem-solving itself be problematic?

February 28, 2021The Big Picture,Reflection and Learning,Blog

Intelligence is usually defined in terms of capacities like the ability to learn, to plan, to recognize patterns and to solve problems. So it has been hard for me – as an advocate of collective intelligence – to come to terms with the profound short-comings of problem-solving.

Problem-solving is universally respected and applied: If there’s a situation we don’t like, we believe it needs to be approached as a problem and solved. If the responsible person fails to solve it well, that’s their fault, not the fault of the problem-solving approach, itself.

In this essay I invite you to consider that problem-solving – as a way of handling troubling situations – has more pitfalls than most of us realize. In an ironic nutshell, there are some problems with problem-solving.

I find the very idea shocking. Problem-solving is so embedded in our thinking and language that it is hard to conceive of addressing challenges without trying to solve them as a problem. The problem-solving worldview is ubiquitous in our culture. I now think that that worldview generates a growing shadow for our civilization – a civilization profoundly dependent on the very problem-solving impulse that is making it increasingly vulnerable!

I’ve been considering how many of today’s “issues” and “crises” are rooted in earlier solutions. Consider, for example, what solution-based Progress looks like when we take account of its downsides:

- Better housing insulates us from “the elements”, thereby serving to alienate us from nature, dulling our instincts and capacity to respond with appropriate insight and urgency to environmental degradations unfolding around us. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Advanced medical care and provision of calories “solve” hunger and disease while expanding humanity’s environmental impact and frequently undermining deeper dimensions of individual, communal and environmental health. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Getting efficiently from A to B and acquiring our favorite products has disrupted Earth’s climate, depleted its resources, and generated massive amounts of garbage and toxicity. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Institutions to support people in need have generated systemic dependency and undermined traditional modes of mutual and communal caring and nurturance. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- The efficiency of money, mass production, mass commodification and mass mobility tend to replace relational interdependence, uniqueness, meaning, reciprocity, community and artisanship. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Communication technologies have transplanted us from communities of place to virtual networks of like-minded people far away, decreasing local social capital needed for physical communal resilience.

People are busily working on solutions to all the solution-generated problems noted above, while the whole interconnected body of life and its support systems are coming apart. I’m not saying we shouldn’t do things “to improve people’s lives”. I’m saying it seems wise to take better account of the downsides of our current approaches because, as novelist Phillip K. Dick notes, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” What we don’t take into account usually comes back to haunt us, sooner or later.

PROBLEMS WITH LINEARITY

Most of the shortcomings of our problem-solving worldview are grounded in the fact that it is fundamentally linear and the world is fundamentally non-linear. More often than not, the bigger the situation being addressed, the more nonlinear it is and the harder it is to understand, predict and control it. We can add to that challenge the fact that our “successful” problem-solving at smaller scales (like a decision to travel by jet instead of train) is generating ever-vaster problems at larger scales, thanks to how many of us are led to prefer problematic options.

This is one example of how our problem-solving efforts take us on an A-to-B fantasy trip from identifying the problem to finding a solution that makes the problem disappear. We believe in this simple story, even when evidence suggests it is incomplete and misleading. When things go wrong, we think that we (or someone) didn’t solve the problem correctly. We don’t think that there might be some issues with problem-solving, itself. After all, we see it working so well for small, simple, mechanical (non-living) challenges like fixing a flat tire – and even for complicated challenges like sending someone to the moon. (See my writeup of the Cynefin framework.)

Unfortunately, the linearity of problem-solving becomes troublesome when it is applied to large, complex, nonlinear situations and systems. These are the most common types of situation faced by organizations, communities and societies today. They are extremely messy even to try solving and, more often than not, when we implement such a solution we generate “side effects” which often become problems that demand solutions of their own, ad infinitum, as suggested by the bullet list above.

Problem-solvers even have a name for the most problematic problems. They’re called “wicked problems” because they are virtually unsolvable. The more alive and complex a situation or system is, the more it features interactive moving parts, vast influential contexts, autonomous agents, and evolving demands on the solvers, themselves, to dance and transform in ways that make any “solution” temporary, at best. All this interrelational movement thwarts our efforts to nail down The Problem and arrive at a final Solution that actually makes the problem go away.

The effort to apply problem-solving approaches to messy, wicked problems tends to not only fail to work as expected, but to generate hubris and tunnel vision in us as problem-solvers. We become captivated by the heroic narrative of generating clear solutions and thus reluctant to acknowledge how such complex systemic problems tend to have many tangled causes and how our solutions almost always generate new problems. We are inclined to underappreciate, downplay, or fatally ignore the evolving web of factors that make a satisfying solution so elusive. We hang on to our linear sense of problem-solving success.

IS PROBLEM-SOLVING ACTUALLY APPROPRIATE IN THIS CASE?

If we want to use problem-solving approaches wisely, we need to recognize where they may not be appropriate, and to deeply understand why that is. It also helps to know what approaches to use instead.

I offer below a list of some characteristics of situations, conditions and systems that do not respond well to problem-solving. None of them are cognitive deal-breakers or impediments to productive engagement; there are alternative approaches that can help us work with them. For each characteristic, I’ve included examples of approaches that would probably work better than traditional problem-solving. As with so many of my lists, this one is not to be taken as comprehensive, but rather as a doorway into thinking differently about this remarkably nuanced topic.

- If we encounter significant novelty and surprises in the problem domain, we’ll need to use less problem-solving and more openness, curiosity, exploration, and creative prototyping. As we learn more, we MAY be able to shift into problem-solving mode, but always very judiciously. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Where the problem domain is embedded in contexts – social or natural systems, histories, assumptions, etc., that seem to be in the background but actually shape or are impacted by the problem domain – we can investigate those larger contexts and convene generative conversations among players in them before attempting problem-solving. Often, deeper understanding of the situation and relations among the players will shift the context in ways that cause the original problem to shrink or dissolve entirely. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Where the problem is linked to other problems – e.g., at different scales, places, times, nodes of systemic causality, etc. – we’d be wise (as above) to undertake investigations and conversations about – and among players in – those related problem domains before even thinking of solving the original problem. Unacknowledged and ignored interconnections between problem domains is a major reason why solutions in one domain create problems in other domains. Of course, the more connections we acknowledge, the more complex we realize “the problem domain” actually is, challenging us to use even less linear approaches. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Where we find true complexity – in other words, constant interactivity, change, evolution, and emergence happening among elements within the situation – our responses require openness, diversity, fluidity, resilience, “dancing” with change and “surfing” the waves and rapids of change rather than problem-solving. Literally “solving” something in such a situation is futile because any “target“ for our efforts is always moving and morphing, often in response to whatever we do (and even who we are). Ideally, our level of responsiveness would reflect the level of mutual responsiveness unfolding among the other elements in the system. Improvisational dance might be the best metaphor for a workable approach. We would not see ourselves as separate, fight against the interactive energies, or push a prefigured plan. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- In response to significant but intrinsic uncertainties, it is most appropriate to respond with humility, intuition, appreciation, and exploring multiple perspectives in search of recognizable patterns rather than just trying to deny or solve the uncertainties so we can be certain enough to start problem-solving again. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- If we’re confronted by a polarity whose elements are deeply interdependent parts of a dynamic whole – such as freedom/equality, short term/long term, individual/group, etc. – their tension cannot be “solved” in the usual sense. They need to be managed for greater synergy, short-term situational prioritization (where one or the other side of the polarity is temporarily prioritized), and a long-term balance that is dynamic, not static. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Predicaments – conditions that simply cannot be solved – challenge us to accept what’s going on, to minimize what harms may be associated with those conditions, to change ourselves as needed[*], and to support each other and the healthy functioning of whatever system the predicament is embedded in. In this, we may find the Serenity Prayer helpful: “God grant me the courage to change what I can change, the serenity to accept what I can’t, and the wisdom to know the difference.” [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Finally, Mystery is always present, inviting us to learn or deepen into the implicit awe-inspiring qualities of life and existence. Such learning and deepening can go on forever. Problem-solving is often a way to skip over that dimension of our experience – but we can always shift into Mystery at any time, simply for its own sake (setting aside the whole problem-solving impulse), or to gain perspective (since certain habits or assumptions can limit our view of what’s important or possible), or to make space for more creativity to help our problem-solving become richer and wiser. This may open the door to some of the less linear approaches listed below….

ALTERNATIVE PROCESSES

Some consultants note that the effort to solve problems can lower a group’s energy – despite the fact that some analytically inclined members of the group may enjoy that mode of thinking. Various exercises – creative, physically active, etc. – can be used make group problem-solving more enjoyable.

But that can make an unhelpful activity bearable. Luckily, there are totally different approaches to deal with undesirable conditions – other than problem-solving. These include the following, which I again offer with all my earlier caveats regarding lists! [Any processes not linked herein can be found here.]

- Active or strategic appreciation. This linked essay lists some process resources for this approach as well as this challenge to our imaginations: “What would happen if we deeply understood what was going on, if we saw and were truly grateful for the positive aspects of it and, in addition, if we used that recognition to help those positive aspects and possibilities become more present and alive in the situations we were addressing?…. [Rather than] pushing what we want to change towards a predetermined outcome… [What if] we’re evoking responses from the aliveness that’s already present or trying to help that aliveness show up more fully among us. As an approach to purposeful action, it’s more aligned to the nonlinear nature of chaos and complexity than traditional problem-solving approaches.” [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

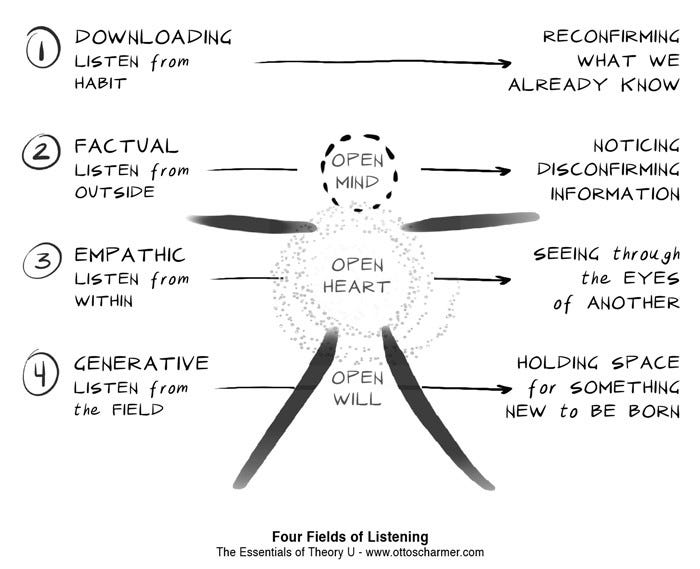

- Conversation that evokes emergent shared understandings of what’s going on and what makes sense – e.g. Dynamic Facilitation and Convergent Facilitation [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Breakout-based gatherings where multiple perspectives on and dimensions of the situation can be explored with like-minded others – e.g., Open Space Technology, Warm Data Labs, and Ephemeral Group Process [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Creating contexts and awareness of relationship, resonance, reciprocity, and co-creativity not just with each other, but with all the elements of the situation or reality involved – e.g., Nonviolent Communication and Braiding Sweetgrass [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Using the challenges of the situation for psychospiritual development, individually or collectively[*] – e.g., Mindfulness meditation and Bohm Dialogue [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Using the challenges of the situation for systemic transformation – as when social change organizers help people see how the unpleasant aspects of their lives arise less from their personal inadequacies than from the dysfunctional systems in which they are embedded and which shape their lives, thereby inspiring them to act to transform those systems. See “the personal is political”

A CLOSING REALIZATION

On a break from writing this, I began to wonder to what extent problem-solving is related to our desire to predict and control, to impact the world and not have it impact us. This adds a wider lens through which to consider these “problems with problem-solving”.

More generally, I’ve been seeing more and more aspects of my work and vision falling into a spectrum between (a) order, prediction and control and (b) reciprocal learning, adaptation and relationship. Creativity and intelligence seem to be important factors at both ends of that spectrum, but (b) involves more CO-creativity and CO-intelligence.

I’ll be writing more on that soon, I suspect…..

Coheartedly,

Tom

Originally published at tomatleeblog

featured image found HERE

I'm interested in conscious evolution as an active and integrated process of personal and social transformation, as well as many subsets of that -- collective intelligence, evolutionary spirituality, wise democracy, emergent economics, etc. My main home website is http://co-intelligence.org

Organizing models for social change: Networks as an inclusive category

Creating social change of any sort requires organizing the people who have an interest in the issue or problem at hand. The global social impact space has a wide range of terms — networks, movements, alliances, consortiums, coalitions, communities, partnerships, forums, initiatives, campaigns, and more — for how people and groups are organized across geographies and topics to affect change. While the titles represent some variations in approach, orientation, and composition, these types of organizing models share a lot in common.

What should we understand about organizing models?

A quick search of definitions highlights the important differences and nuances of various types of organizing models. [1]

- Coalition — a temporary alliance of distinct parties for joint action.

- Consortium — a group formed to undertake an enterprise beyond the resources of any one member.

- Alliance — a formal agreement or association to further the common interests of members by merging efforts.

- Partnership — a formal relationship involving close cooperation between parties with specified and joint rights and responsibilities.

- Movement — a diffusely organized or heterogeneous group of people or organizations tending toward or favoring a generalized common goal.

What all of these models have in common is that they are about connecting and facilitating interactions between people or organizations to take action together. They convene groups around a shared purpose and merge efforts and resources towards collaborative action.

Organizing models also typically define who is involved, why, and how they plan to achieve their goals.

· Who — the people or organizations that have an interest in the issue or problem at hand and that are coming together.

· Why — the common interests amongst participants and the shared goals they seek to achieve together.

· How — the ways in which the participants are connecting, interacting, merging efforts, and undertaking collective action to achieve their shared goals.

Networks as an inclusive category of organizing models

At Collective Mind, we use the term “networks” to encompass this expansive range of organizing models and their common components.

Networks can come in all shapes and sizes. They can range from the informal — for example, a group of professionals with a shared interest in reducing inequality in their field who communicate via a Slack channel — to the highly formalized, such as a global network with organizational members in each country who formally apply for membership or an alliance of European NGOs formed on the basis of a legal arrangement for sharing funds and achieving shared goals. The category of network can include a pan-African movement organized through national associations and local community groups, all of whom participate in achieving a shared vision, as well as the hybrid setup of a US-based nonprofit that runs its own programs while also coordinating a network.

Whatever their labels, these networks seek to collectively and participatorily achieve goals that none of the participants can achieve by themselves. At their core, they integrate participants who have common interests and work together to achieve shared goals. That is where the power of networks lies.

[1] Definitions taken from Merriam-Webster, Cambridge Dictionary, and Dictionary.com

Originally Published at Collective Mind

Featured image by Kubko

Collective Mind seeks to build the efficiency, effectiveness, and impact of networks and the people who work for and with them. We believe that the way to solve the world’s most complex problems is through collective action – and that networks, in the ways that they organize people and organizations around a shared purpose, are the fit-for-purpose organizational model to harness resources, views, strengths, and assets to achieve that shared purpose.

The Square, the Tower, and the Circle:

February 17, 2021The Big Picture,Blog

The Blind Spot in the Stewardship of Locally Led Systems Change Networks

The Plight of the Social Activist

Many social activists can relate to the following scenario. They sign up for an intensive training in a beautiful nearby region, with the intention of networking with fellow activists and learning about social change and innovation. The timing is perfect — they feel like they’ve been working alone for years and are struggling to see the impact of their efforts. They sense that what they’ve been doing has a significant impact on the people they touch, but at the same time they feel like a mere drop in the ocean.

They keep seeing the same patterns of behavior and destruction around them, regardless of the enormous amount of energy and creativity they’ve put into their work. The problem just seems too big and intractable.

They think they’ve found the perfect training — one in which they’ll learn about systems thinking and how the tiny efforts of a small group of committed individuals can add up to create massive, exponential change. Linking is a central idea, and the concepts of ‘network’ and ‘network weaving’ are thrown at them throughout the training. They learn about complex systems, emergence, tipping points, and the viral spread of ideas, all while participating in discussions and creative dialogue sessions where a deeper understanding of their peers’ interests and struggles is achieved. They partake in fascinating group dynamics and games meant to challenge certain mental models and an unsustainable amount of post-it notes are consumed in an effort to define goals. As a group, they go through the usual stages of development: forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning before waving goodbye to their colleagues and facilitators.

In the time following the training, the group stays in touch — those who live close to each other organize meetings and casual get-togethers, while others join via zoom. Some of the participants even go as far as successfully planning activities together. However, others begin opting out as the pace of life returns and the retreat effect starts wearing off. It’s hard to meet given everyone’s schedules and other issues arise such as internet connectivity and disagreements on the preferred communication platform.

It’s not long before everyone reverts to the same routine of hunting for the next funding opportunity in order to put food on their tables. The training becomes a fond memory for the activist. They keep in touch with the new friends they’ve made, but the vision of a strong coalition to bring about big systematic change now seems very distant. New relationships were formed and a network was weaved, but they feel that they’re back where they started, focusing on their own work and wondering whether their small efforts will indeed produce any meaningful change amidst the powerful status-quo.

Disrupting the Pattern

If you can relate to this story, you’re not alone. Many activists, change makers, social innovators and civil society leaders have gone through this experience. It is a pattern.

What is the blindspot of social networks? The governance in the networks that fuel social change movements. Despite the recent interest in the shift towards networked strategies for social change, there is still a lot to be explored concerning the questions surrounding decision making and the establishment of network policies together with its collective mission.

A deep and structured conversation about network governance is required and needs to be included in the design process of network initiation. It is an integral part of the responsibility of NGOs who convene networks and should be held and carried out by the funder and donor community worldwide.

Systems Change Networks and Their Governance

In one way or the other, most social movements are a form of challenge to established powers. That power can take the form of an oppressive regime, an unfair economic system, or corrupt systemic status quo. The latter is the most difficult to tackle since it does not have a simple hub and spoke structure that can be understood and dismantled piece by piece. Examples of systemic status quo are racism, environmental violence, or protracted civil conflict.

This article addresses the struggles related to shifting systems, particularly the ones that have no linchpin or clear leverage points: no regime to topple, no significant companies to sue, and no peace treaty to negotiate. There may be no clear endgame or road towards it and no clear definition of success or failure, other than a sensible change of the current status quo.

These are the most difficult struggles to pursue for social movements and the networks fueling them as they entail a bitter provocation to the network members. They may be asking themselves:

“Is the way we self-organize to change the status quo not a mere reflection of the status quo itself? Aren’t we simply replicating old patterns of working and “fighting” that contain within themselves the seeds that created the current status quo in the first place?”

If taken in earnest, this provocation gives rise to a tension that many social change movements face and fail to overcome. The movement needs to become agile and organized enough to plan and coordinate many different small scale actions across the spectrum of the complex field they are operating in. A network strategy is said to be adopted: instead of a few large scale actions coordinated by a central committee, many diverse and synchronized small scale initiatives are planned. These initiatives are not organized or mandated centrally. Still, they are attuned to a set of shared, high level, mission statements and principles, leaving the details of their execution to the local change agents.

Yet, this mere synchronization requires a form of governance and hierarchy. There are decisions to be made, actions to be taken, people to speak to, and money to spend. But the typical form of governance where a leader is elected by majority vote leads to a network topology that is not suitable for dealing with complex problems. This approach tends to degenerate from the concentration of power and authority held by a few individuals in the network, which is exactly what social movements wanted to avoid in the first place.

The Square and The Tower

In the 2018 book The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power, author Niall Ferguson takes the reader through history’s defining moments by putting in perspective the role that individuals and social networks played in them. The book uses the metaphors of “the square” to symbolize the place where informal, loosely structured social networks end up convening, and “the tower” to represent the formal top-down hierarchical power. The author challenges the somewhat romantic idea that networks or movements spun with the help of modern communications technologies have the ability to replace traditional systems of governance. Although Ferguson’s analysis sounds about right, it is missing the contribution of another geometric shape: the circle.

Governance is a heavily loaded word. It brings about associations with concepts such as government, bureaucracy and power over people. Yet, every system, be it natural, artificial, social, biological or mechanical, needs a form of self-regulation. We call this process of self-regulation “governance”. It is a process by which the system senses the outside environment and adapts its actions in order to fulfill its purpose accordingly.

How to achieve this process of self-regulation while balancing the tension between collective purpose and individual freedom is the value proposition of Sociocracy. Sociocracy has been around since the mid-XIX Century and has the circle as its building block for decisions and sense-making. It’s a system of governance designed around the values of transparency and equivalence but with inspiration from cybernetics (the science of how systems use and exchange information to self-regulate).

In Sociocracy, decision making takes place in a Circle of Shared Power rather than in the Square of the Loudest Voice, or the Tower of Power-Over. It is also aimed at optimizing resource efficiency where decisions are made by consent instead of consensus which usually results in endless debates among network members. By consenting to a decision you are not necessarily agreeing with it, but you’re not objecting to it either; and this, as subtle as it may sound, makes a world of a difference.

Another aspect of Sociocracy which makes it a perfect system of governance for systems change networks, is the way it balances agility with accountability. On the one hand, working on a complex system requires agility, which involves the ability to pivot on a moment’s notice based on real-time information and significant changes in the local environment. This is incompatible with rigid, heavily bureaucratic and procedural governance systems. But procedures and bureaucracies were invented for a reason. They provide for traceability and accountability. Sociocracy solves this tension by letting power flow to the node of the network which is most impacted and closest to the action. In this case, the power flows to the local change agents acting within a very well defined domain. Those who are most affected by a decision are empowered to make the decision, while at the same time are accountable to the “aim” (domain of action) of their circle members.

Transparency, communication and accountability across the organization are accomplished through an interlinking circle structure.

Each circle is connected to the rest of the organization through specific roles that interface with a “general circle” which is then connected to a “mission circle”. In this way, information and feedback flow through the system at all levels of the organization. This forms an organizational structure resembling a set of nested circles that provides a flexible hierarchy where decisions are made at the most local level possible, while maintaining the integrity and alignment of the entire system.

Empowered Networks

The power of isolated local change agents is bounded by their radius of reach, their community, their field, and their organization. When embedded in a systems change network, their power can be leveraged by clever usage of the network effects. Nevertheless, this is only if there’s a governance system in place that invites their voices to be heard, incorporates feedback loops, and is well structured yet malleable enough to allow for agile adaptation to the changing, dynamic environment.

Such a system is not straightforward and one shouldn’t expect groups or nascent networks to find a solution for the critical governance tension quickly. Sociocracy is just one example of a system of governance that is more aligned with the requirements of systems change networks.

In addition to fostering connectivity between local change agents and nurturing social spaces for cross-pollination of ideas, funders and donors are missing the opportunity to invest in setting up a governance system which empowers the network to thrive.

This governance system does not need to be perfect. Its effectiveness comes from an agile approach. Look for what solves the immediate problem while supporting your network values and is “good enough for now, safe enough to try” (a principle used in Sociocracy and Agile Methodology).

The year 2020 will be remembered in the history books for many disruptive events. It will also be looked back upon as the year that our civilization’s complexity and interconnectivity became revealed in unprecedented ways. In our role as supporters of social change movements, we are being called to rise to the occasion and earnestly address the blindspot around group governance and power so that we can effectively respond in these volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous times.

Originally published HERE

Featured image by Bruno Munari

Pedro Portela is the Founder of the Hivemind Institute, a think tank and action research organization in Portugal dedicated exclusively to prototype new models of local organization, advocating for more systems literacy and proposing networked approaches to complex social problems.

Bernadette Wesley is a Sociocracy and Communication Trainer ~ helping organizations and communities self-organize and co-create together in healthy, conscious, and productive ways

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

The Power of Communities in Uncertain Times — Part 2

February 10, 2021The Big Picture,Blog,Transformation

The questions we ask today will define the future we create tomorrow…

When the Stranger says: “What is the meaning of this city?

Do you huddle close together because you love each other?”

What will you answer? “We all dwell together

To make money from each other”? or “This is a community”?

Oh my soul, be prepared for the coming of the Stranger.

Be prepared for him who knows how to ask questions.~ T.S. Eliot, The Rock

The reckless and rapacious excesses of the politicians, the converging crises — from the pandemic to natural disasters to socio-political collapses, the years of systemic and structural inequities and imbalances, and failing economies have all culminated to a point where the whole world is blowing up in our face. The situations may be as diverse as the long march back home for Indian migrants, the anti-CAA protests in India, or the eruption of anger against the killing of George Floyd in the U.S.A.

However, underlying the surface differences are deep-seated common ills: resounding failure of structures and systems built on narratives of privilege, power, and profit, the “othering” and oppression of the “different” and dispossessed, marginalization and brutalization of the perceived enemies of mainstream political agenda, and an overbearingly extractive, exploitative, and exclusive economy. But now the Stranger Eliot wrote about is here in the form of the pandemic. And it is forcing us to ask ourselves some very tough questions.

As the virus sweeps across nations, an obsolete and failing world order stand revealed in the form of increasingly draconian and dictatorial policies, unchecked police brutalities, political perfidies, economic turmoil, and deep social inequities and injustices. The world that has been teetering on the brink for a long time has now tilted over into chaos.

The blizzard of the world

Has crossed the threshold

And it’s overturned the order of the soul.

~Leonard Cohen

But tenuous sparks of hope are visible against this dismal and disorienting backdrop in the form of communities of people rising in protest against decades of discrimination, in solidarity with their fellow humans, in anger and anguish but with unflinching faith. And it is this unwavering belief, this fierce commitment toward co-creating a “world that works for all,” this refusal to be subjugated frightens the powers that be.

So, they double down on polarizing, dehumanizing, and concocting “fake enemies,” keeping alive an environment of constant unrest and turmoil. The last thing they want are people recognizing and honoring their deep inter-connectedness and inter-relatedness with each other. Perhaps not surprisingly, acknowledging our inescapable and ineradicable inter-connectedness is precisely the lesson the pandemic seems to be driving home.

The grand design of the pandemic appears to be to simultaneously underscore all the fault-lines while giving us opportunities to re-imagine a different and thrivable future. It is shining a light on our civilization’s shadows so that we can collectively, courageously, and creatively overcome them. For centuries, we have sustained and propagated the Story of Separation. We have tolerated and submitted to systemic inequity, injustice, and intolerance. We have, for far too long, averted our gaze while the answer was always blowin’ in the wind. It is time now to step into the Story of Interbeing.

As individuals, we dream of an abundant, thriving, and resilient world, but we do not have the capacity to actualize it. Yet, when we come together as intentional communities, we have immense power to effect change. The pandemic is asking us to honor our inter-relatedness and offer our collective wisdom in the service of envisioning and actualizing a regenerative future. This is an opportunity to hospice what no longer serves us and midwife the seeds of a future based on the principles of Interbeing.

“There is no power for change greater than a community discovering what it cares about.” ~Margaret J. Wheatley.

This article is a tentative exploration into the possibilities, promise, and qualities of intentional communities of diverse and committed individuals collectively exploring this liminal space we are in, honoring and deeply living the questions, and holding the space for what wants to emerge. The power of privilege running rampant the world over can only be countered by the purpose of communities.

It is axiomatic that we are at a threshold in human existence, a fundamental change in understanding about our relationship to nature and each other. We are moving from a world created by privilege to a world created by community. ~Paul Hawken

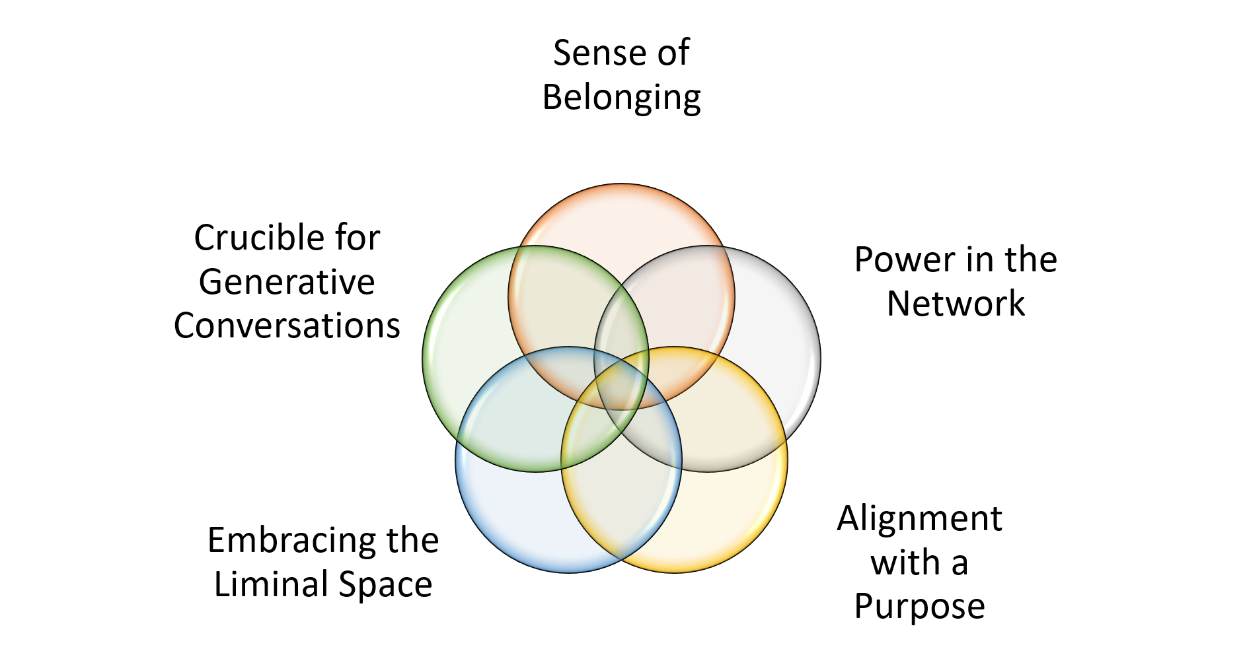

These communities must necessarily be diverse. Only by inviting and respecting a kaleidoscope of perspectives and worldviews, expertise and experience, seeing and sensemaking capabilities can the communities co-create narratives and metaphors that move us toward an emergent future. By aligning remarkably diverse people around a purpose, the communities help us to see and sense the world through a multiplicity of lenses so that we avoid the dangers of a single story. Thoughtfully designed and facilitated communities become crucibles and evolutionary spaces for generative conversations and insightful synergy among varied perspectives, thus giving rise to new ways of being and acting in the world.