Governance is how we choose to be together

An illustrated story of liberatory governance practice

Storytelling — like governance — can take many forms.

When choosing new ways of being together, we begin with ourselves — in our bodies, hearts, spirits. The choice to be in governance rooted in mutual care is an embodied one. Once it rests within us, the practice begins.

Accordingly, the story of governance practice is a multi-sensory one. It takes shape in the colors, textures, voices, sounds, and sensations of our beloved communities — it is multi-dimensional.

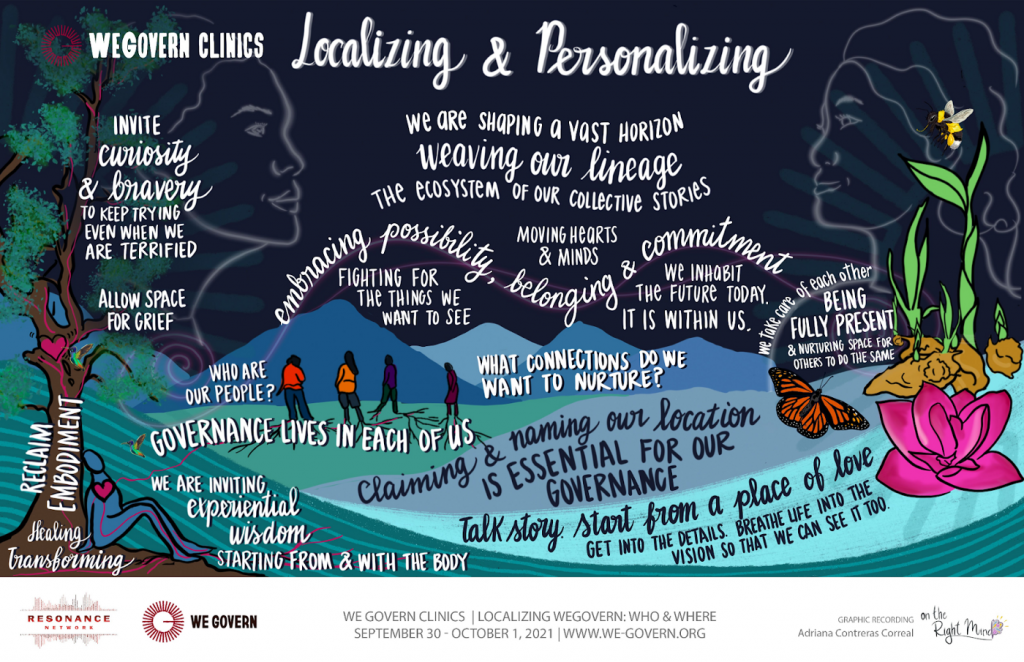

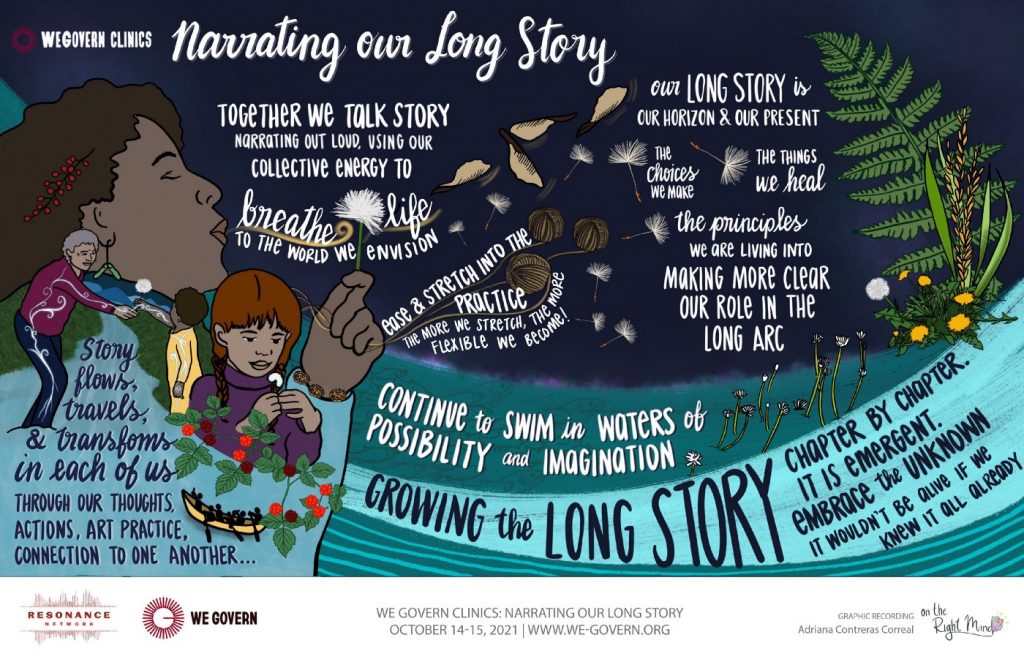

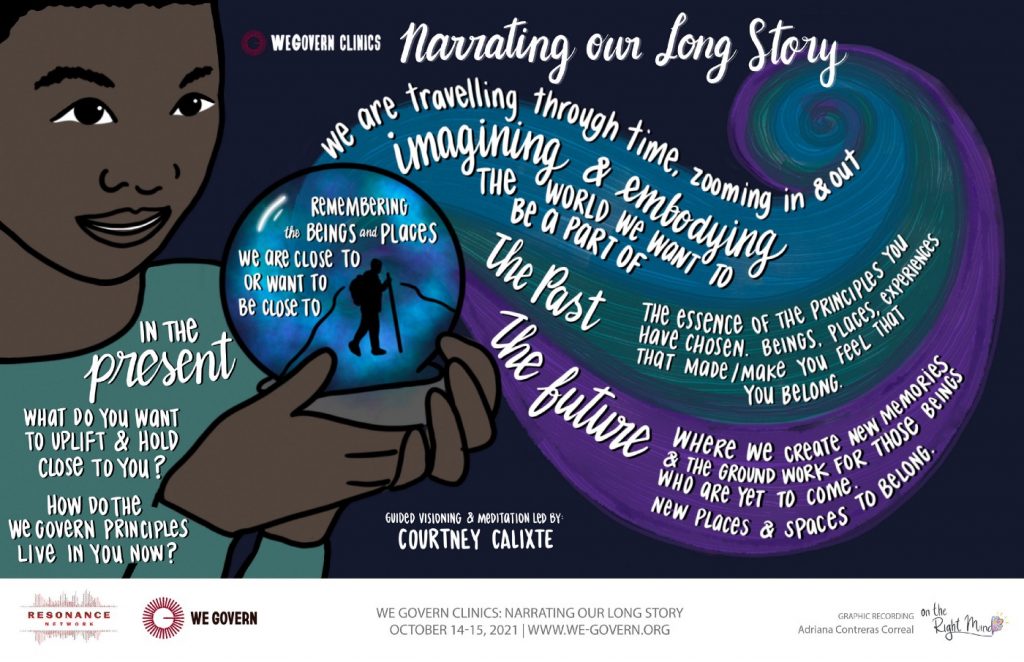

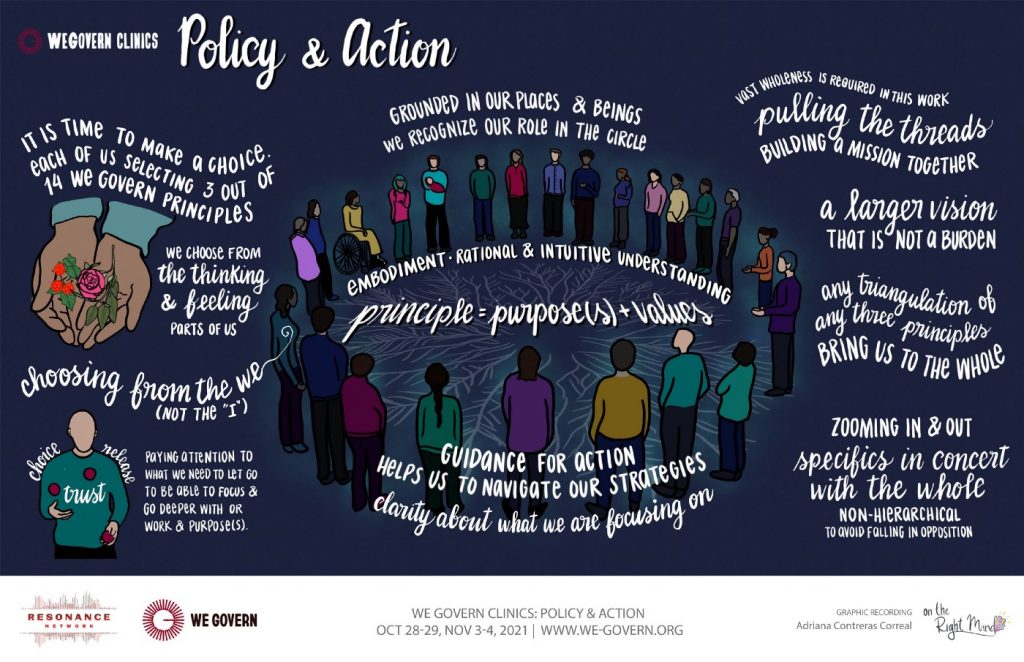

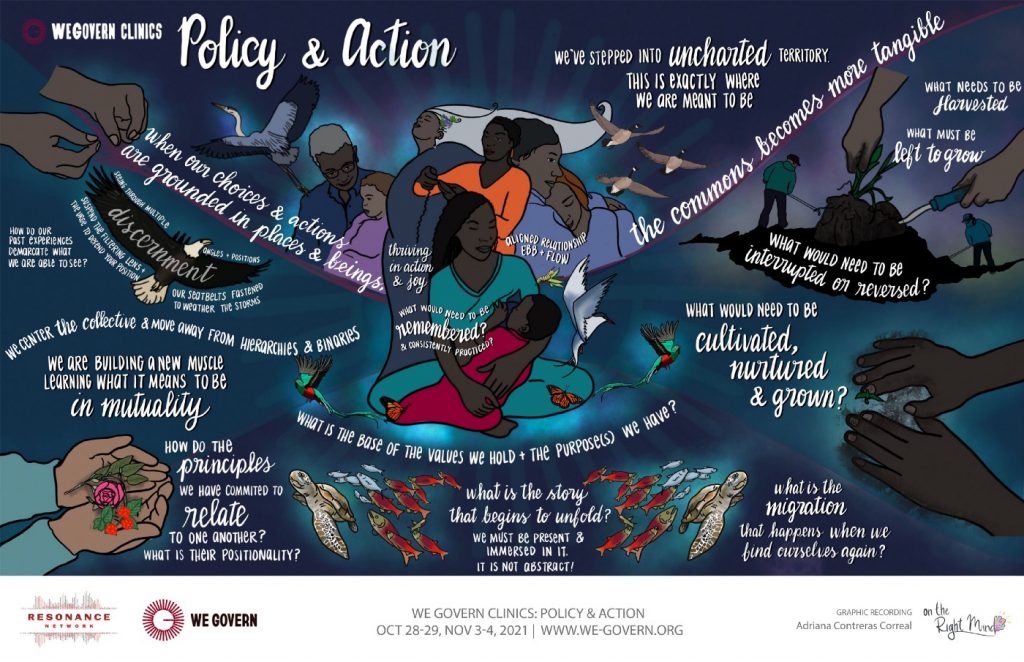

Last year, a group of worldbuilders came together with a shared commitment to collective liberation — and the governance principles we’ll need to bring it into being. Together, we moved through a series of clinics to deepen our collective governance practice.

What follows is a constellation of words, images, and musical offerings to describe this journey into liberatory governance. These images are the work of our beloved Adriana Contreras Correal of On the Right Mind. Deep gratitude to Adriana for sharing her gifts with us.

We invite you to enjoy our practice playlist and delve into the story below…

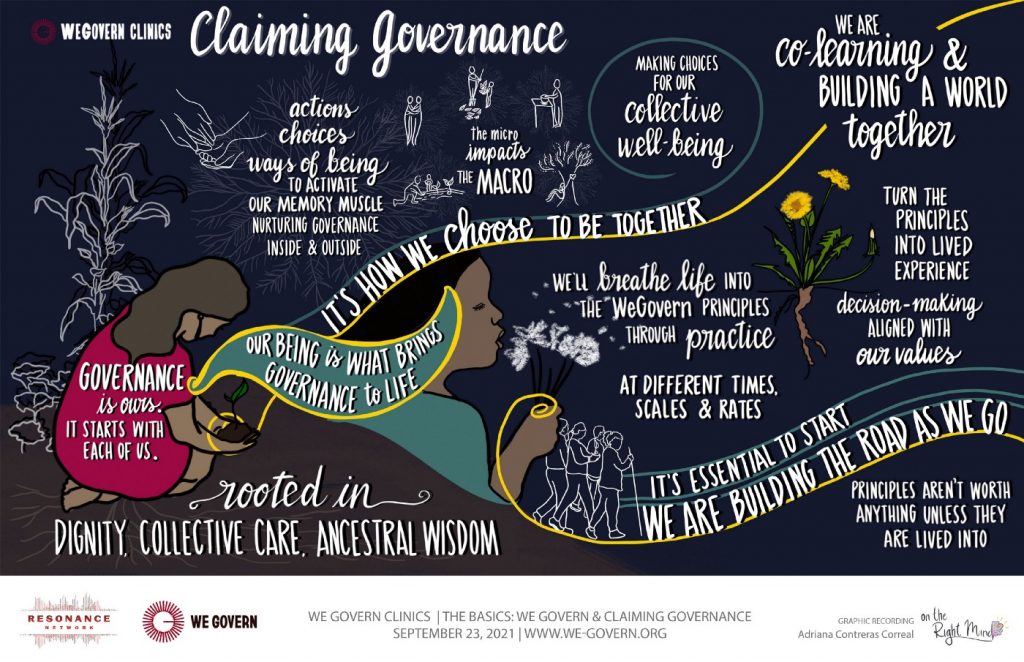

Collective governance begins with a choice: to commit to the ways of being that enable all beings to thrive:

Transformation begins when it’s personal: once we’ve committed to collective governance, we begin by grounding in place. Our work begins at home:

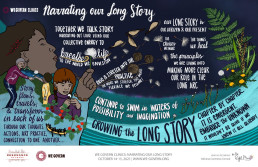

As our practice takes root, we continue illuminating the path toward what is possible, by narrating our visions for our communities into story:

Holding close to our stories of liberatory futures, we focus in on policies and actions we will need to sustain a world beyond violence — a world where all beings can thrive:

Originally published at Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

MAKING LARGE EVENTS PARTICIPATORY

This blog was originally published in October, 2019, when we couldn’t foresee that most large events would cease. As we anticipate meeting again in person, I hope the approaches here give you ideas. You might like to check out my new meeting design coaching services.

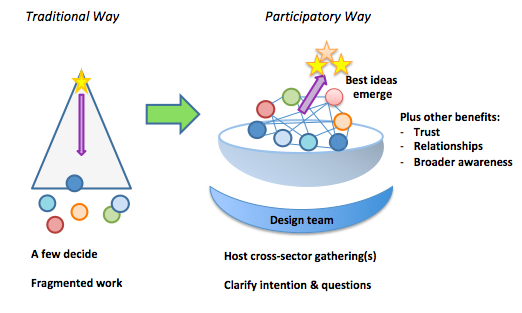

It’s possible to make large events participatory and interactive. Here we share our latest inspiration and approaches, from recent work with events from 50 people to over 200 people. The topics and audiences vary, yet the desire to inspire and connect people, enhance learning, build connections, and advance work beyond the meeting is the same. Here’s what goes into our secret sauce for creating a participatory, inspiring event:

Participation starts in design: Working with a design team that includes representatives of the people who will be participating in the event helps ensure the event format is relevant and effective. This group can:

- Bring varied perspectives to clarify the context and conversations that are needed now. For example, with a state-wide food network that’s been underway for five years, we landed on this strategic question: How can the structure and approaches of the network galvanize and support action and momentum at the local, regional, and state levels? It took some thinking and conversation to get clear that this was the most powerful question for this moment. We brought in case studies to spark the conversations.

- Provide input on the format of the meeting and who to invite and how, e.g., you can access the broader social and professional networks of those in the room to learn about other people, organizations, and initiatives who could be invited.

- Serve as ambassadors for the vision and the meeting/initiative, spreading the word, helping with invitations, and sharing feedback they are hearing.

For example, we co-facilitated the annual meeting of the Greater Nashua Public Health Network, with a focus on building a trauma-informed community. The design team helped us get a sense of how much training had been done so we could tailor the content of the training portions. We agreed on a clear set of desired outcomes and went through several rounds of an agenda design, tailoring and improving it each time, based on their feedback.

At the event, start with stories: Getting people sharing stories early in the day builds relationships and creates a warm, welcoming environment. Our approach is inspired by an exercise called Radical Acceptance, which I learned from taking improv classes with Boynton Improv Education in Portsmouth, NH. This simple exercise builds a sense of emotional safety and encouragement for everyone to speak up. I modified it slightly by doing the following:

- At round tables, invite each person to introduce themselves and share one brief story of something going well in their work. Invite everyone to respond with a “yes!” or any other enthusiastic positive response. Then the next person goes and the group does the same. Across the room you hear “yes!” and clapping and laughter, and see fist bumps.

- In another variation at the Nashua meeting, we asked each person to share one thing they appreciate about Nashua/the region and put it on a post it note. We used the same process I mentioned and then collected these and had a graphic facilitator make a poster of the themes.

This only takes 10-15 minutes. Sometimes people pick up on the “yes!” and bring that positive response into other parts of the day, often with a shared laugh.

Offer inspiration/new ideas and new voices: Beyond the standard keynote presentations and skill-building workshops, consider having shorter TED-talk type or PechaKucha presentations (presenter has about 7 minutes to talk with 20 image slides) and featuring voices beyond “experts,” e.g., youth, those with lived experience, people from marginalized identities or communities.

Host cross-pollinating small group conversations: The World Café process taps the ideas of everyone in the room and allows people to make new connections and learn from each other. At an anti-racism gathering of 200+ people from Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, we invited people to talk in a group of four with people from their state about what is working in anti-racism work. In the second round, they mixed to a new group of four with people from other states, sharing themes from the previous conversation, and then talking about what more was needed. With 200 people, this meant we had 50 four-person conversations each round (100 total), which is a lot of learning and information exchange…and fertile ground for new relationships and collaborations to form.

Allow space for self-organized deeper dive conversations: All of the conversations and ideas percolating through the first part of an event can be given a space to land and deepen if you design space for that. Inspired by the process of Open Space, here’s an example of how we organized this at the event with 200 people:

- During the morning sessions, we asked people to submit topics they’d like to discuss with others at an Open Space/deeper dive conversation session that afternoon.

- Over lunch, we grouped these into about 16 overall topics. I made folded table tents with a table number and name of the topic and put these out on the round tables. I sketched a chart showing table numbers and topics, took a photo, and put it up on a slide.

- When that session began, I invited people to join the topic they’d like to discuss and walked around with a roving microphone to introduce the topics and show which table was where, with the slide image as another guide.

- We asked for a note-taker at each table. For topics where lots of people showed up, we invited them to split into several tables. At the end, we heard brief highlights from the table conversations.

At another event, we had time for people to rotate to a second topic table, while some people stayed at the first one, building in another layer of connection and cross-pollinating.

The range of topics that were suggested were far beyond what our design team would have thought of, and we learned which areas had the most interest. People had the freedom to initiate or join conversations and connect with others with similar ideas, concerns, and questions.

I wish I could somehow visualize and learn all the seeds that got planted at these events. We offered the fertile ground – so time will tell what grows!

Beth Tener is a leadership trainer and coach who helps social change leaders live their values as they address complex challenges, such as transitioning to a clean energy economy, disrupting racism, and revitalizing communities. She is passionate about bringing people together in ways that unlock and ignite personal, group, and community potential. She is the founder of New Directions Collaborative, based in Portsmouth, NH, and has worked with over 200 organizations and collaborative networks.

originally published at New Directive Collaborative

featured image found here

Adapting a network’s theory of change

Collective Mind hosts regular Community Conversations with our global learning community. These sessions create space for network professionals to connect, share experiences, and cultivate solutions to common problems experienced by networks.

On September 22nd, 2021 we met with Carri Munn from Context for Action and Amelia Pape from Converge for our first Community Conversation of the fall. Carri and Amelia shared their experiences collaborating with network teams to adapt Converge’s theory of change to their networks and the process and successes of co-creating a shared theory of change with network leaders.

Highlights from the conversation

Complex problems are by nature nonlinear and typically must be addressed from many angles at once. This is why networks, in their ability to connect and facilitate collective action between people and organizations, can be successful and impactful in creating system change in complex environments. As defined by our co-hosts, a theory of change describes how a network can create systemic change by harnessing the interdependence of the network system – its members.

The way networks create system change – or their theory of change — can often emerge in phases. The conversation outlined these phases, beginning with connecting the actors within the network system, working towards building trusting relationships and an understanding of members’ contexts. This is the foundation necessary to reach the coordination phase, when regular communication and coordination starts to occur between people within the network, people are supporting the work and each other, silos are starting to break down, and information, value, and learnings begin to flow from the connections that have been created. From here, the collaboration phase emerges and members begin to recognize a shared purpose within the larger system and opportunities to collaborate within it. It is these emergent collaborations that begin to create and perpetuate more and new collaborations and, eventually, system change and impact at scale.

This phased framework is a way to talk broadly about a network’s theory of change. However, network leaders often need a specific and contextual theory of change to effectively communicate to and strengthen the network. Our co-hosts shared an example of using this framework to support a network interested in transforming a broad theory of change to one that represented their network’s specific activities, as a means to communicate and collaborate more effectively with its members and stakeholders.

Using the phased theory of change framework — connection, coordination, and collaboration — our co-hosts described their process, which started with using surveys and conversations to gather information from the network about the challenges, barriers, and opportunities that existed within the network system in its current state, and to describe the optimal system impact, or the realized vision, they hoped to achieve. These became inputs for a virtual Mural storyboard session where they facilitated a smaller group of network participants to articulate what they hoped to create and achieve in each phase and how they viewed their roles and relationships within these phases. The storyboarding exercise was a way to help the network articulate how they would create the conditions for impact and collaboration to emerge that would be considered those of a healthy network and then use those outcomes as a tool to communicate with and bond the network.

What also emerged from this conversation was the critical role of network coordinators in theory of change processes. Coordinators are often the catalyst in orienting networks to see the bigger picture. As facilitators of a complex system, it often falls to them both, by necessity and design, to engage members in conversations about how they see themselves as part of a larger whole and how to contribute to transformational change in the network system.

Miss the session? View the recording here.

Sign up for the Collective Mind newsletter to receive these in your inbox!

Thanks again to our co-hosts, Carri Munn and Amelia Pape!

Get involved

Have your own experiences developing a theory of change? Tell us about it in the comments below.

Join us for the next Community Conversation!

Or email Seema at seema@collectivemindglobal.org to co-host an upcoming session with us.

original article published HERE

Experimenting Towards Liberated Governance

Over a year ago, Vu Le published an article about the current models for nonprofit boards. The title “The default nonprofit board model is archaic and toxic; let’s try some new models” doesn’t bury the lede. Of the current models, Le writes:

“Over the years, we have developed a learned helplessness, thinking that this model is the only one we have. So we put up with it, grumbling to our colleagues and working to mitigate our challenges, for instance figuring out ways to bring good board members on to neutralize bad ones or having more trainings or meetings to increase ‘board engagement.’”

At Change Elemental, we have been experimenting with some new governance models, informed by the work of our clients, partners, and many others in the field who are trying out new structures and ways of governing. For example, Vanessa LeBourdais at DreamRider Productions has shared principles and practices of “evolutionary governance”, and Tracy Kunkler at Circle Forward has supported our learning about consent-based decision making. Countless other groups who have continued to uphold and practice historic, ancestral, Indigenous, and intergenerational structures of governance—and have informed these other values-aligned governance models—have catalyzed our learning.

Here, we offer a specific window on the evolution of our board, including some practices we’ve dreamed up, borrowed, and re-remembered to align governance with our values in a nonprofit system set up to default to white supremacy, paternalism, power over, and other oppressive habits.

The following questions have formed the basis of our governance and leadership evolution (we’ve shared more about our leadership evolution in recent blog posts here and here):

- How might we realize deep equity and liberation in leadership and governance?

- How might we evolve leadership and governance structures to share power and work in more networked ways?

- How might we align leadership and governance practices and culture with our values?

Our journey began a few years ago when our board and core staff team began to get curious about what it might look like to think about our board as mycelium. Mycelium are fungal networks that spread across great distances within soil (and sometimes underwater) and process nutrients from the environment to catalyze plant growth, supporting ecosystems to thrive. In our context, we use mycelium to refer to the powerful network of tendrils and roots that connect our board and core team to other people, groups, and organizations, enabling us to turn toxins into nutrients and nourish ourselves through our relationships to ensure collective thriving and care.

Here is what we’ve learned so far in our governance evolution (from the core team perspective—more from our governance team coming soon!):

Shifting language from “board” to “governance team” helped us reframe the governance team’s role.

Early on we shifted from referring to our board as “a board of directors” to a “governance team.” Tracy Kunkler of Circle Forward offered this definition in a small group experiment on governance we facilitated:

“Every culture (in a family, a business, etc.) produces governance — the processes of interaction and decision-making and the systems by which decisions are implemented. Governance is how we set up systems to live our values, and leads to the creation, reinforcement, or reproduction of social norms and institutions. Governance systems give form to the culture’s power relationships. It becomes the rules for who makes the rules and how.”

Shifting language supported us to shift our mindsets about governance. This language guided us towards greater clarity about our own governance team’s role: co-creating systems and practices that can support and catalyze us to live our values. It also deeply shifted how we both hold and reimagine the boundaries between the 12 people on our governance team, our core team (staff), and other partners to be more porous and center collaboration, emergence, and our interconnectedness.

However, because shifting mindsets requires shifting patterns and practice, this switch in language isn’t simple. We have noticed that we sometimes revert to using the term “board” rather than “governance team” when we are talking about potential barriers that the board may present or “traditional” board responsibilities such as fiduciary oversight. This is a work in progress and when we find ourselves reverting to old language, it is a signal that we might be in older practices, patterns, or ways of thinking about our relationship to the governance team and its role that are no longer serving us or our work.

Practicing liberatory governance is having one foot on land and one in the sea.

Getting clearer on our governance team’s role deepened our sense of what it might look like to realize deep equity and liberation in governance. We began to understand what “liberatory governance” could look like for us—a governance team that partners with us to bridge between current reality and the future we’re building by: moving the organization towards greater alignment with our values; and co-creating liberatory systems and ways of working together that can transform the larger oppressive systems we’re operating within. We talk about this internally as “having one foot on land and one on water,” a metaphor Hub member Elissa Sloan Perry shared from Alexis Pauline Gumbs. Gumbs hears best with “one foot in the water, one foot in the sand.”

In our organizational context, the “water foot” attends to things like our vision, uninhibited aspirations, values alignment, and acting today in ways that prefigure the world we want to see. The “foot on land” takes into account the world as it is, such as the requirements and legal constraints of our 501.c.3 tax designation, and current financial realities and access to other resources, where trust-based relationships can sometimes become transactional or even litigious. Our governance model values both “feet” in its awareness and decision-making. When we make decisions, the “water foot” leads with the “land foot” as a valued, supporting, and crucial partner.

Creating multiple, fluid points of connection across the staff and governance team helps build the relationships and trust necessary for shared leadership and power.

Building trust and mutual accountability are at the heart of our evolving governance structures and practices, just as we have found it to be in building toward shared power and leadership at the staff level. This work is more time-consuming than conventional governance models so we needed to build our collective capacity for sensing what is actually too much time. We also needed to strengthen our skill and capacity for generative conflict including discerning when to: enter into conflict and tension; sit with it so that we can reflect and discuss later; and/or intentionally let it go. This has meant getting more comfortable with sitting in discomfort when conflict can’t (or shouldn’t) be resolved immediately.

Some simple structures and systems support us in developing these capacities and discerning what is needed to build trust and move through conflict. For example, we wanted more interaction between our core team (staff) and the governance team, but didn’t want to necessarily add more large group meetings—we wanted connections to be deep and purposeful. To create purposeful connections, where a broad range of staff and governance team members could develop relationships and bring their unique gifts, we opted to have governance team co-chairs work with a staff liaison. The staff liaison partners with different staff, bringing different people into conversations with the co-chairs and other governance team members where their experience, wisdom, and gifts are critical. The co-chairs and other governance team members then connect together and separately into different areas of work based on their interests, skills, and what is needed.

We also evolved our governance team meeting structure to have staff members join for key sections of the meeting. We share the agenda in advance and offer some guidance to help staff decide when they might join or when they might opt out of a meeting. Additionally, staff and governance team members now caucus separately at the end of each governance team meeting to debrief and raise unresolved issues with the intention of sharing back what needs the full group’s attention. The caucuses support greater truth-telling across the governance team and core team, deepen our understanding of each other’s perspectives and help us dig into conflict with love and rigor.

Grounding in shared values is critical for practicing liberatory governance.

If you were to review the specifics of our governance team’s role, you might not find anything surprising or “new.” The difference is in how the governance team carries out these responsibilities – with a rooting in shared values with staff and commitment to working through differences in values when they show up.

In recruiting and engaging governance team members, we haven’t just sought out individuals who conceptually agree with our values (which were reflected in our recruitment criteria), but people who are game to experiment on what it looks like to make decisions rooted in those values. People who already embrace and practice inner work, multiple ways of knowing, experimentation, and emergent strategy—and who are looking to upend traditional governance team models and create and remember anew.

Even with the perfect container, structure, and systems, it’s the people who make up our core team (our staff) and governance team – their own values as well as their willingness to be in the generative tension that helps support shared values – who have accelerated our work in shared power and leadership both on the core and governance teams. Together, we are living into our vision and deepening our practices of shared leadership and shared power to shift conditions towards love, dignity, and justice.

Look out for more learning from these experiments in liberatory governance in the new year!

Natalie Bamdad (she/her/hers), joined Change Elemental in 2017. She is a queer and first-gen Arab-Iranian Jew, whose people are from Basra and Tehran. She is a DC-based facilitator and rabble-rouser working to strengthen leadership, organizations, and movement networks working towards racial equity and liberation of people and planet.

Mark Leach (he/him/his) has over thirty years of experience as a researcher and management consultant. Mark has a particular interest in strategy, leadership development and transition, and issues of equity and inclusion in organizations.

Originally published at Change Elemental

Banner Photo Credit: Kirill Ignatyev | Flickr

The Art of Measuring Change

What are your associations with words such as “measurement”, “evaluation” or “indicator”? For many people these words sound annoying at best, and there are good reasons for it. Yet - given the fact that you clicked on this article - it’s also very likely that you are motivated to contribute to social change, and the main intention of this article is to share about the beauty and collaborative power of attempting to measure it. What I am not doing is offering quick solutions, the same way art is not a solution to a problem. Rather, it is an invitation to step back, look at the nuanced process of change with curiosity and an inquisitive mind, and maybe discover something new. The article is also available as a dynamical systems map.

In a nutshell

There are two ways of reading this article:

- Exploration mode: Use the systems map provided above and use the visual representation to navigate through the article more flexibly.

- Focussed mode: Stay here and follow the flow of the article.

Here already a quick overview of the main points and arguments:

- There is a good reason to be skeptical of impact measurement. If the approach taken is too simplistic and/or mainly serves to validate a perspective (e.g. of the donor), it’s almost impossible to measure what truly matters. Rather, such an approach further perpetuates existing power imbalances and puts beneficiaries at risk. (section: The dangers of linearity)

- The measurement of social phenomena has to pay justice to the intricacies and complexities of a project, a program, or any given action. This requires understanding, which puts empathy, listening and collaboration at the centre of an empowering approach to measuring change. (section: About potluck dinners and “power with”)

- Meaningful indicators serve as building blocks in the attempt to capture social change. An indicator is meaningful when it not only follows the SMART principles, but is also systemic and relevant, shared (understood and supported by all stakeholders) and inclusive (aware of power relationships). (section: Indicators that matter)

- Complexity science can provide an alternative scientific paradigm to understand and make sense of our world and, hence, to measure change. (section: Coming back to complexity)

- It’s time to equally distribute power, namely the ability to influence and shape “the rules of the game”, or potentially even the kind of game that is being played in the first place. A crucial step towards this is describing and defining what desired social change is and how we go about measuring it in a collaborative way. (section: Synthesis)

The starting point

I have been working in the field of impact evaluation and measuring social change for around 6 years now. I’ve interviewed cocoa farmers in Ghana, developed surveys and frameworks, crunched Excel tables of different sizes and qualities, mapped indicators, and held workshops on tracking change in networks. Doing all of this is way more than a job to me. I have met wonderful people on this path, have been part of impactful projects and really had the feeling of being able to contribute in a meaningful way.

To me, impact evaluation is an ambitious, creative and collaborative application of complexity science (more on that later). It can be a deeply empowering process that reveals hidden opportunities and structural challenges, creating empathy between groups of people.

And it can be harmful.

The dangers of linearity

Let me share a definition with you to explain what I mean:

“An impact evaluation analyses the (positive or negative, intended or unintended) impact of a project, programme, or policy on the target population, and quantifies how large that impact is.”*

I agree with that definition in general, yet when it comes to the details in language, my opinion differs significantly. For example:

- Nobody is or should be a target. We don’t shoot projects, programs or policies at people, we work with people.

- Quantification plays a role, but we should also qualify impact.

- It is not said who has the power to define “positive or negative”, and “intended or unintended”.

These are not simply trivial semantic differences. All too often I experienced situations where impact evaluation was used by organisations to prove and validate the effectiveness of their services, rather than to truly understand the perception and consequences of what they offer.

Here is an example of what I mean: A couple of years back I had the opportunity to visit cocoa farmers in Ghana for an impact evaluation for an NGO. We found out that, yes, the NGO’s activities are actually having an effect and are contributing positively to farmers’ income. But we did not capture in writing the fact that most farmers stopped growing subsistence crops for their own consumption, hence making themselves more vulnerable to global trends and market prices. A few months after I left, the market price for cocoa dropped significantly. We did not capture it as it was not part of our evaluation framework or our mental model about what counts as relevant information.*

This is what happens all too frequently: We have pre-defined and pre-conceived notions of what counts as a data point, and what doesn’t. This again is usually based on a linear model of thinking (aka “A” leads to “B”), not accounting for the complexities and intricacies of human interaction and social systems. I have talked to so many people in the field that were frustrated, stating something along the lines of “we don’t measure what is truly relevant”.

To put it another way: If empathy and understanding are not at the centre of impact evaluation, both as the foundation and the goal, then it might be (unintentionally!) used against the people we want to benefit. It’s like having a knife in your hand. You can use it to prepare a delicious meal, but also to hurt yourself and others.

About potluck dinners and “power with”

Let’s dig a bit deeper into that: We’ve learned that what we do in impact evaluation is to assess the change attributed to an intervention (a project, program, workshop etc.). You do something and then something else happens. Now, we want to understand the “somethings” and how they are connected. This is not as simple a task as it may seem. Reasons include:

- We humans love to make our own meaning. You (and your organisation) probably know what the intervention is, but others perceive it fromtheir own perspective and life reality.

- Change is like air: Ever-present and hard to grasp. The “mechanics” of change can’t be pinned down easily and require us to look at context & conditions. Similarly, we know how difficult predictions are. Should we trust the weather forecast? For the next 3 to 5 days probably, but beyond that?

- There is power in the game: Oftentimes, multiple stakeholders and their multiple opinions are involved in an evaluation. There is nothing wrong with that per se, yet it is important to acknowledge.

The art of impact evaluation, therefore, is not to publish fancy reports, but to apply it in such a way that it deepens the internal understanding of issues at hand and strengthens the collaboration between actors. When this is the case, It builds empathy and human connection, and enables stakeholders to jointly develop shared meaning and scenarios for social change and transformation.

In other words, impact evaluation is based on and deepens listening. Listening not only to people, but to their context and to groups of people, to underlying and invisible challenges and hopes.*

In a more recent project I worked on we called all stakeholders together from the very beginning. It was clear who “has the money”, but we also shared the ambition to collaborate on a level playing field. As a consequence, we co-developed the project’s vision and the evaluation framework. We made clear that the first round of data collection also serves the purpose to understand what is relevant; and that the project goals will be further developed based on the “reality on the ground” rather than the content of the funders’ strategy paper.

We created the space for a genuine dialogue, and the data collected further strengthened the mutual understanding and trust in the group and in the process. It revealed both further challenges and where the leverage points are for creating systemic impact. It also became clear that power is not only linked to money.

“What makes power dangerous is how it’s used. Power over is driven by fear. Daring and transformative leaders share power with, empower people to, and inspire people to develop power within.” (Brené Brown)*

What we did was to ask a different question than normal. The central question was not “how can one central stakeholder prove their impact?”, but rather “how can we jointly contribute to desired change for a matter that we all care about?”. Shifting the question means that stakeholders and their individual contributions are valued differently, and that the quality of interaction changes.

Speaking in the metaphor of our delicious meal: We did not go into a restaurant where you tell somebody what should be cooked for you. Rather, we sent out the invitation to join a potluck dinner. Organising a dinner in this way does not happen at random. It requires clarity on roles and contributions, as well as shared agreements (e.g. on when and where to meet). The fundamental difference to a restaurant visit, though, is that it values participation and what each stakeholder (dinner guest) brings to the table, which in turn requires a mindset of being curious and open to surprises.

So far so good, but how do we actually measure change?

Jannik Kaiser is co-founder of Unity Effect, where he is leading the area of Systemic Impact. His desire to co-create systemic social change led him down the rabbit holes of complexity science, human sense-making (e.g. phenomenology), asking big questions (just ask “why” often enough…) and personal healing. Having worked in the NGO sector, academia and now social entrepreneurship

Originally published at Unity Effect

featured photo by Adi Goldstein on Unsplash

The illusion of hopelessness

The war in Ukraine is a symptom of something bigger— and within reach

In times of war, we are led to believe we are powerless.

We are told that violence is inevitable, an unfortunate part of the way things are. And that the way things are cannot change.

As world events have transpired over the last two weeks, this illusion has begun to splinter

* * *

Russian military forces invaded a sovereign nation on February 24th. Within days, the United States, the European Union, and other nations announced a series of economic sanctions on Russia. At the same time, countries of the European Union waived visa rules for Ukrainian refugees–allowing those fleeing war to enter the EU without having to seek asylum.

Homes across Europe have opened their doors to Ukrainians fleeing war, and President Biden announced that Ukrainian refugees would be welcome in the US “with open arms.”

These moves were swift and unprecedented. Rules that had long existed were replaced with new ones. Systems changed as people and countries moved together in response to a humanitarian crisis.

How quickly rules can change when we want them to.

How malleable systems can be when we agree on what is right.

* * *

Russia’s attack on Ukraine, like all wars, is a symptom of a worldview of domination and extraction.

Like all wars, it exists amid other symptoms and consequences of this worldview: modern dependence on oil and the interests of the fossil fuel industry; unmistakable racism at the Ukrainian border as Africans were systematically turned away.

And the global coordination to condemn Russia’s attack and support the Ukrainian people was made possible, in part, by white supremacy: Western sensibilities were stirred by seeing white refugees. Meanwhile, escalating humanitarian crises in Afghanistan, Palestine, Yemen, Syria, Somalia, and Ethiopia have not been met with the same swiftness.

Imagine a world where all people in need were met with dignity and humanity. Where violence and harm was met with resounding care.

Imagine systems of governance that hold these values above all others.

* * *

In times of war, we are led to believe we are powerless by those who benefit from our silence. We are led to believe our collective systems cannot change by those who benefit from the way things are. Meanwhile, worldviews of domination and extraction continue to shape our reality and perpetuate harm.

As the war in Ukraine has unfolded, we’ve also seen a wave of dehumanizing legislation against queer and trans young people, increasing threats to reproductive justice, and an alarming epidemic of homelessness continuing in the US, all while COVID cases spike in Europe and Asia.

When we understand that all violence is a symptom with the same cause, we can also see that we are not just spectators to what is happening — in Ukraine or right beside us.

There is hope, and the hope is us.

* * *

“There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation.

The challenge is in the moment; the time is always now.”

~James Baldwin

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Originally published 3.16.22 at Reverb

Seeing the World Through a Network Lens

June Holley offers Network Weaving Workshop, another training slide deck for use in your organization or network. It provides an introduction to many network concepts and includes a number of activities such as speed networking, mapping your network, and the Network Weaver Checklist.

This slide deck is particularly good for sets of organizations who are not well connected. As result of this session, they would be starting to see the world through a network lens.

The slides are offered in pdf format, but we are also sharing a link to the google slides. Create a copy of the presentation and save it as a new name in your google drive. This way, you can modify them to adapt the presentation to the particular group you are working with.

Access the Network Weaving Workshop slide deck HERE.

June Holley has been weaving networks, helping others weave networks and writing about networks for over 40 years. She is currently increasing her capacity to capture learning and innovations from the field and sharing what she discovers through blog posts, occasional virtual sessions and a forthcoming book.

featured image found HERE

THE TAPESTRY: Weaving Life Stories

You are invited to listen to The Tapestry Podcast.

The podcast is about bringing people together to explore the rich, woven textures of our narratives. Our stories are impactful and in listening to the stories of others, we learn more about our own power, claim our purpose and pursue our passion. The fabric of our lives as women is strong, resilient and when we come together, we can make a beautiful piece of work to inspire, support and sustain our personal and professional lives. Although designed for women 50 and above, the wisdom shared is ageless. Join us as we share, laugh hysterically, cry, and keep it real all at the same time.

Some of The Tapestry's most recent episodes include:

THE STORIES BEHIND THE DATA - Meme Styles

In 2015, Meme Styles founded MEASURE to promote the use of evidence-based projects and tools to tell real-life stories behind the numbers. As a catalyst for systems change, MEASURE has grown to a fully operational nonprofit social enterprise that provides free data support to Powerful Black and Brown-led communities. So far the organization has provided over 3000 free data support hours to Black and Brown - led organizations.

CREATING A PERSONAL NETWORK FOR TRANSFORMATION -- June Holley

June Holley has been weaving networks - and helping other learn to weave networks – for over 40 years. Much that she learned is included in The Network Weaver Handbook, 400 pages of simple activities and resources for Network Weavers. She also created www.dev.networkweaver.com, a site with many free resources and a blog authored by over 40 network weavers.

BOUNDARIES IN BUSINESS AND IN LIFE FOR 2022 - Kimberly Oneil

Kimberly O'Neil is an award-winning professor, executive leader, and social good expert. She was the youngest serving African American woman City Manager in the United States. As a veteran senior government and nonprofit executive, Kimberly has used her voice to impact policy decisions while lobbying in New York City and on Capitol Hill. She now works within the social sector and leads Giving Blueprint, a consulting company with a mission to impact social change through the development of strategic partnerships and growth plans within the social sector.

CRITICAL CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RACE - Amber Sims

Amber currently serves as the Executive Director of Young Leaders Strong City, a nonprofit focused on youth development, leadership, and racial equity. She was formerly the Director of Regional Impact for Leadership for Educational Equity, an educational nonprofit focused on leadership pathways in civic engagement. Previously, Amber led workforce development at Workforce Solutions Greater Dallas Opportunity Center. Her theory of change was to emphasize the connection between education, workforce, and dual generation impact.

Other guests have included:

- Dallas Maverick CEO and President Cynt Marshall

- Leah Frazier , 2-Time Emmy Award-Winning and 10-Time ADDY Award-Winning entrepreneur

- Paula Stone Williams, internationally known speaker on issues of gender equity, LGBTQ advocacy, and religious tolerance

- Rafia Zakaria, author of Against White Feminism (W.W. Norton, 2021) and Veil (Bloomsbury, 2017) and a writer for the Guardian, Boston Review, The New Republic, The New York Times Book Review and Al Jazeera America

- Gretchen Bauer, Luxury handbag manufacturer

Find all The Tapestry episodes HERE

Dr. Froswa’ Booker-Drew is a Partnership Broker. Relational Leadership Junkie. Connector. Author/Speaker/Trainer. Co-Founder, HERitage Giving Circle. Currently, the Vice President of Community Affairs of the State Fair of Texas, she has been quoted and profiled in Forbes, Ozy, Bustle, Huffington Post and other media outlets around the world. In addition, she has been asked to speak on a variety of topics such as social capital and networking, leadership, diversity, and community development to national and international audiences. This included serving as a workshop presenter at the United Nations in 2013 on the Access to Power.

featured image found HERE

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Businesses without Bosses: from hard-nosed leadership to sustainable, self-managing systems

As many of you know, I’m very passionate about helping people understand and experiment with self-organizing.

Joella Bruckshaw and Julian Saipe are executive coaches who have a wonderful podcast series called ‘Behind The Screen’ where they share leadership insights with high profile leaders. In this series of impromptu discussions, Joella and Julian, along with their invited guests, discuss success, the characteristics we choose to reveal, and those we choose to keep behind the screen - engaging thoughts on leadership, performance, authenticity and having fun.

In Episode 12 of the podcast series, Joella and Julian talked with me about Self-Organization.

Our conversation explored how “businesses without bosses” can thrive, just as nature’s own eco-systems do. We also discussed how coaching could facilitate a transition from hard-nosed leadership to sustainable, self-managing systems, where purposefulness itself is the outcome.

Access the interview on Behind the Screen podcast at: iTunes/Apple HERE & Amazon Music HERE

June Holley has been weaving networks, helping others weave networks and writing about networks for over 40 years. She is currently increasing her capacity to capture learning and innovations from the field and sharing what she discovers through blog posts, occasional virtual sessions and a forthcoming book.

featured image found HERE

Governance – the overlooked route to transformation: How can we best organise for change?

What are the current governance approaches and ways of organising that are being used in attempts to create systems change? What would more systemic governance approaches for our work look/feel like and how might we transition to these?

Part one in a series of four exploring the future of how we govern and organise. Co-written by Sean Andrew, Louise Armstrong and Anna Birney

“Every attempt to write a new human story converges upon just one mundane, heartbreaking problem: How shall we come together, work together, create together? How shall we organise?”

Nilsson, Paddock and Temmink, 2021, Changing the way we change the world (Draft manuscript)

At the heart of change is how we think, relate and act. While these ways of being weave in and throughout our ordinary everyday experiences, they are not always given the intention and continuous attention they need. We believe how we relate, work together, and organise are cornerstones of change making. How we find ways to bring awareness to these elements really matters, and is easier said than done. They need just as much attention as the structural shifts that are required in the coming decade.

With this in mind, we are exploring governance as the place of untapped potential that can enable transformation today and into the future.

We’re defining governance as: The forms, structures and social processes that people and institutions use to create and shape their collective activities.

As such, we, and many others we’re working with and are inspired by (Beyond the Rules, The Hum, Reinventing Organizations, Going Horizontal, Practical Governance, Organization Unbound, Lankelly Chase, Shared Assets, Patterns for Change, Leadermorphosis and Barefoot Guide Connection, to name a few) are calling for governance approaches that reflect systemic principles that are suited for complex adaptive systems. Many of those we’ve listed are experimenting with elements of this, each adapting these to their contexts like Transition Movement and their shared governance approach, or CIVIC SQUARE, who are applying their mission and values into the organisational structures and processes – from how they do recruitment through to how they do financial planning.

We’re increasingly noticing internally, through our own organisational experience at Forum for the Future, and through our systems change strategy, collaboration and coaching work with others, that many of us subscribe to dominant forms of governance that are designed for a complicated, not complex world. We’ve noticed that sometimes, without intention, our own patterns of organising and those of many of our partners are perpetuating the structures, dynamics and patterns we are trying to shift. For example, we take centralised or hierarchical decision making approaches even though we want to enable greater ownership over a project which can come through taking advice-based decision making approaches where those closest to the challenge are part of the process.

Systemic governance on the other hand enables self-organisation (how a group of people organises their time, attention and resources in ways that meet the urgent necessity of the moment). It cultivates the emergent practices (and enables new system patterns) that help us align to regenerative and distributive approaches that better mimic our living systems.

Our inquiry into governance

After exploring new forms of organising, over the last 18 months at Forum we have been exploring two governance inquiry questions:

- What are the current governance approaches and ways of organising that are being used in attempts to create systems change?

- What would more systemic governance approaches for our work look/feel like and how might we transition to these?

To respond to these questions, we’ve been reflecting on our own organisational life while also learning from current and past collaborations we’ve convened or participated in over the past decade.

What is governance?

So how do people understand governance in their context? Through our inquiry we found that peoples’ understanding and expression of governance varied and was even sometimes quite vague. While governance meant different things to people, depending on their role or context, the people we spoke to talked about it in a few distinct ways, the ‘elements of governance’.

Elements of systemic governance

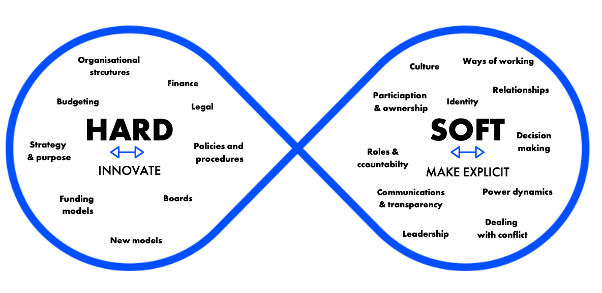

Systemic governance has both soft and hard elements.

Part of the reason why we tend to think of governance as a fixed process is that we often associate it with a few rigid components. From this exploration we realised that governance is in fact made up of a whole spectrum of elements, which while distinct, together create a unique governance context you may find yourself within, be that in an organisation, a movement, a collaborative endeavour, a community or really any place where people come together to organise something. By naming a spectrum of elements it expands the view of what governance is and how these parts form a tapestry.

We’ve created the figure 8 (below) as a summary of what we’ve heard, recognising that one way of distinguishing these elements is looking at the ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ elements. While the hard and soft elements can sometimes feel in tension with each other – they are in fact interdependent and together they form part of the governance landscape we have to traverse together;

In reality – we recognise these elements can be interchangeably hard/soft and are in symbiosis. Some will be visible and explicit and others invisible and implicit, depending on the context and people’s experience. For example, a “hard” element such as finance might actually be very hidden in an organisation without financial transparency or a “soft” element such as communication and transparency might be experienced overtly as lacking and be a visible gap in ways of working.

Innovating the hard and visible elements of governance

Most of the governance approaches we explored focused on the hard and often more visible, explicit structural elements of the organisation. These seemingly felt easier to figure out with clear problem > solution tactics. For these hard, visible structural elements of governance, people talked about inherited “best practices” that often took the form of compliance protocols. When working systemically, challenges can come when the ‘hard’ or ‘visible’ parts of governance are too rigid and fixed. We found that people working on complex challenges were often bound by these constraints and were yearning for ways to disrupt, reimagine, and innovate these ‘hard’ elements.

One hypothesis we are working with is that the hard stuff (the what) can be a transitory tool and a trojan horse for prioritising the soft stuff (the how).

The soft, invisible elements are the hardest part of governance to shift

The “soft” elements of governance are the implicit less formal cultural components of how people relate and organise. It’s often less tangible and thus harder to shift. Systemic governance is a constant practice of probing, sensing and responding to the dynamic nature of these elements in changing contexts. We found that these elements are too often submerged and therefore if we want to develop resilient adaptable governance approaches we need to bring to the surface and made explicit the soft cultural elements. While these elements are often deprioritised as they are unseen, they are still aspects of governance that materially impact the lived experience of people working within different organising forms.

Why is it so hard to work with the softer issues? The nature and quality of our relationships is the foundation of any governance. Questioning, challenging and reconfiguring established relationships is hard. It can take difficult conversations and processes to bring in different perspectives and overcome unhealthy power dynamics. Bringing self-awareness, paying attention to relational dynamics, creating space to listen and honestly share and transparent communications are the starting points.

Reframing governance as a journey

We heard people thinking about governance as putting structures and processes in place and thinking the rest will follow. Any of the words and connotations people mentioned pointed to governance as something that is fixed and hard, a static thing you set up on a one-off basis when in fact governance approaches are alive, can be enabling and need to be seen as a constantly evolving journey. We’ll explore some more of these governance myths in the next blog piece.

Sign up for the newsletter to get the next blog piece directly to your inbox.

Governance as an overlooked intervention or leverage point for change

These elements of governance play out in all of the many ways when we come together – be that in a multi stakeholder collaboration, across teams or functions in a large organisations, in communities, within networks or distributed movements. Governance is central to any form of organising or organisation creating change. We need to support others to imagine and implement new governance approaches that demonstrate and model how we can operate systemically, as a fractal of the change we are cultivating in the world.

What next?

We offer this figure 8 framework as a way to open up a different conversation about governance and acknowledge it is just one framing. We’d love to know if this resonates with your experience and how the challenges of hard and soft elements play out for you?

We’ll be writing two more pieces in this series. One to explore some of the governance myths we’ve been uncovering through our inquiry (e.g. governance helps us control things). And a second to dig deeper into some of the core systemic governance elements you might start to pay attention to now as critical yeast to influence your organisational practices and experience.

In 2021, we’re starting to explore some of these ideas with fellow travellers who have similar experiences in their context. If these ideas resonate with you or you want explore them more – get in touch with Sean s.andrew@forumforthefuture.org or Louise l.armstrong@forumforthefuture.org

Background context

At Forum for the Future, our governance inquiry is one of our three live inquiries (power, governance, regenerative) we’ve been exploring over the last 18months. This inquiry approach supports our aspiration to be a learning organisation that keeps questioning the assumptions nested in our purpose and supporting structures, processes and practices. Our belief is that these inquiries are helping us continuously become a system-changing organisation that is using our own experience as a site of learning, and as an expression of the change work we’re trying to do in the world. This inquiry has been greatly inspired and supported by those in the field who have been, and are, experimenting with ideas and approaches to governance. This piece is part of our ongoing Future of Sustainability series. In 2021 we’re exploring the narratives and practical interventions needed for transformation in the coming decade.

Read next:

- Exploring transformational governance together Governance can be transformational. When we set our sights on changing the world, we also know that governing well goes beyond preparing our own organisation, network or movement for the future. How do move beyond tweaking the way things currently work and apply governance to transform the ‘systems’ that operate in our society that maintain injustice, oppression and inequality (such as race, patriarchy and class)? (PART 2/4)

- Reimagining governance myths Part three in a series of four exploring the future of how we govern and organise. This piece looks at how people think governance happens today and challenge five commonly held governance myths. (PART 3/4)

- The governance flywheel In this final installment of our series on governance, we introduce the “governance flywheel”1 which highlights three fundamental linked areas that if they are deliberately seeded and nurtured, individually and together, can create the momentum needed to cultivate and grow healthy governance systems. (PART 4/4)

Originally published at Forum for the Future

An enabling, empathetic and courageous leader. I questions and challenges the way things are done, models what is possible and enable others to do that too. Sees potential and nurtures it in people and ideas. Living change while knowing how to strike how to strike the balance between adventure, rest, work and care and nurturing.

For another way of thinking about governance alternatives see Resonance Network's post and media toolkit : THIS IS HOW #WEGOVERN