Turning the stone: embedding systems thinking in the everyday

The context

Images

Isn’t it interesting how frequently as human beings we turn to metaphor? Sometimes these images are so embedded in the everyday that we don’t see them for what they are. We talk about ‘just ploughing on’, ‘turning over a new leaf’ and much more. Why? Because we don’t feel, think and communicate solely in mechanistic term, we are not ‘desiccated calculating machines’. We think in patterns, through resonance, emotion, stories and intuitive connection as well as logic.

Metaphor evokes in us things the literal cannot. It uses the poet’s deftness to reduce the messiness of the world, rejects the technocrat’s straight line sketch of reality. Metaphors also offer shortcuts to submerged mental models or situations, containing in their DNA bundles of previous inter-related experience and learning. I find images can be useful touchstones or motifs around which to organise my thoughts or re-centre activity or purpose. ‘Be more water’ etc.

Systems

Given this, it’s not surprising that imagery and metaphor feature heavily in systems thinking.

Over the past six months I’ve been learning about systems thinking approaches as well as systems change — their practical application in the cause of social justice or similar ends. I’ve been exposed to an intoxicating array of philosophies, tools, narratives and claims. Inevitably some have resonated more strongly than others. A couple I have found a bit vague (but probably didn’t understand) and a couple I have found a bit opaque (and definitely didn’t understand).

But the process of learning has been quite liberating. It has given me new ways to think about the universe I exist within; who can ask for more than that?

Imagine if a toolkit existed which allowed you to pick the lock of whatever complex policy or operational challenges you were dealing with that day. But also somehow captured the shifting beauty of a thousand starlings in flight or the majesty of the moss covered forest-as-organism. Something that gave definition and structure to all the intuitive system-craft we develop simply by being tenacious and creative in our work. That to me is the appeal of systems thinking.

Systems change in the everyday

Some of the approaches I have come to know take hard work, safeguarded time and the willing collaboration of colleagues. Others flit around at the paradigm level, triggering unconscious mindset micro-recalibrations. The variety is at times overwhelming.

So when I asked myself what artefact I wanted to produce to mark the end of my School of System Change Basecamp programme I thought I would consider practical ways to weave embed systemic practice into the everyday.

After reflection I concluded first one thing and then another. Firstly, that identifying and developing the mental and behavioural pre-conditions which allow systemic thinking to flourish is probably more important than striving to develop deep technical understanding of specific tools — after all no plants will grow in a barren field, no matter how packed with potential the seed. And secondly that I wanted to use emblematic metaphors to pin down the most important of these core attitudes, from which a number of simple, everyday systemic practices could then flow.

So the three sections below are a simple — and imperfect — attempt at that. Three images to lodge in my head, and perhaps yours too.

The images

Turning the stone

I have a memory as a child of turning a large flat stone in a wood and becoming enthralled at the universe-in-miniature beneath it. Insect life, leaf mulch, moss. The dynamic equilibrium of decay and fertility, death and life.

Although it’s impossible to pin down what systems thinking/change represents to any single person, for me it is a world-view build on a deep curiosity about the universe and our place in it. It’s hard to be open to other standpoints, learn or develop without an open mind (and an open heart too). A sense of ongoing intellectual and social inquiry can turbo-change any job which requires tactical relationship building, political weather reading, policy landscape navigating and hard decision making.

Ways to turn the stone:

- Deliberately immerse yourself in media and news sources you know you’ll disagree with. Take time to mentally articulate why you disagree with the arguments and be wary of jumping to conclusions. This is actually quite hard to do! The voluntary sector in the UK, for instance, has an obvious bias towards the soft left politically but I hear few people challenging the system to actively seek out opposing views and force the remaking of arguments for the full range of world-views. If you find your ideas shored up by the process that’s great — like a vital aircraft component that’s been stress-tested to near destruction in the workshop it is now ready for use in the outside world. However you may find your ideas slowly changing — it’s all part of ‘exposing your mental models to the light of day’ (Donella Meadows). [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- ‘Get the beat of the system’ (DM again) — set up a rolling meeting with an inter-disciplinary cast representing the most obvious system viewpoints around which you are working. Or convene a space with four or five experts from the same discipline. Get a monthly Zoom/Team invite in the diary and the admin load is light. Help set the tone and model behaviour at the beginning then sit back — see what people bring. It’s amazing the insights, thoughts, ideas (and yes rants) people share, once they are convinced of the fact they are within a group of trusted system colleagues, outside the more formal spaces of government forums and rigid agendas. Sometimes this more explorative space may feel unfamiliar so you may need to sell it as an informal advisory group of some kind. Convening isn’t about just ‘doing the admin’ it’s about setting a tone, making people feel valued and respected, ‘holding the space’ and modelling behaviour that you wish to see others exhibit.

Building the spider’s web

There are three basic elements in any system — data points (people, perspectives, organisations, cells, trees), the connections between them and a uniting, animating purpose. My observation from policy work is that too much attention is paid to the things themselves and not enough to the connections between them.

Building a network of contacts — and entrepreneurially convening flexible spaces within it — may again allow you to get the beat of the system and develop a more richly detailed (though still partial) map of the territory. A fancy name for this might be ‘distributed cognition’, but I think of it as building a web.

Ways to build the web:

- At the most simple level it could be consciously focusing on the relational. Almost all roles and ways of exploring the world involve working with and through others so relationships are obviously key. Systems leadership across organisational boundaries is impossible without high-quality, sticky and trusting relationships. These will support all future work from developing shared campaign positions to negotiating the finances of a major joint operational undertaking. Thinking of relational work as the work and not just a means to doing the work might help.[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- If getting into systems change feels a bit like joining a secret society then it follows that you must identify and cultivate your fellow travellers. They will not appear according to rank, status or job description. Some will be formally trained and others not. Carving out space and time is key here, which is why I’ve started some thinking about a systems change learning club with an emphasis on the fun, informal side of systems exploration.

Looking into the pond

Knowledge of self precedes almost all other forms of knowledge. The wisdom of the ages tells us that we must know ourselves before turning to identify problems and solutions in the external world — ‘physician, heal thyself’.

There is no two ways about it — to work systemically is to work reflectively. The whole idea is about taking a step back and what is that other than an instruction for reflection?

The image of a still pond reveals itself to me here. Mirror-like, but not a mirror. A surface broken by debris, imperfectly reflecting a face.

Ways to look into the pond:

- Building simple reflective practice into the everyday. Do you have a key series of meetings or a super important stakeholder relationships to develop? Or perhaps a colleague you are struggling to get on with? Or a knotty policy issue dancing before your eyes? Try journaling. Don’t overthink it, use a physical journal or a note-taking app like Evernote to get some stuff down. This is usually about the wisdom of the moment so try to do it immediately after the event rather than in hindsight (when our brains begin to impose post-hoc rationalisation). I remember doing this after my first board meeting and breaking it into ‘head’ and ‘heart’. The first covered the mental and bodily experience of a potentially stressful situation, the second provides analytic commentary on how events unfolded and how things could be different next time.[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- The pond does not reflect just the individual but the system itself. One of the School for System Change’s systemic practices — which I love — is ‘enabling the system to see itself, hold the whole picture’. Think about the causal chains that (nominally at least) link the key data points within the system you are working on. For me it might be something like: minister is keen on a policy, directs senior officials; officials develop policy framework; resource devolved to local government level; commissioner commissions provider; provider CEO sets out a vision; ops director mobilises a service; practitioners make the magic happen for people in recovery; person in recovery volunteers as peer mentor. (You can make it more or less detailed as you see fit.) Now typically most data points (people in this instance) are familiar with only their neighbouring one or two points but much less so with the ones further up or down ‘the food chain’. Short-circuiting those connections can have powerful results. I recently organised a trip for a very senior civil servant who had taken on the treatment and recovery brief. We brought him, and other officials, to a recovery service in North London to listen and learn from senior public health representatives, local government commissioners, frontline workers and people in recovery. And in that room in Tottenham the system was presented with a mirror and — fleetingly — could see itself and understand its shared purpose. The officials walked away remembering that policy-making is not an end in itself but an embodiment of the social contract in action; communal resource being deployed to high quality create public services. The frontline workers walked away feeling that policymaking at the centre is hard, but has good people attempting to address that hardness. Things click into place. ‘Ah, I get why that join up with criminal justice doesn’t work properly, as you’ve had your budgets hammered’. ‘So that’s what assertive outreach is, I had always wondered’. ‘So which agencies should we try and bring together at a local level to provide accountability back to the centre?’ ‘I can see it now, this is why we do what we do — communities improved, families healed, citizens recovering connection and meaning’.[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Finally I hope the pond will reveal the embedded nature of our locations within multiple overlapping systems. And the see-sawing of feelings this realisation brings — greater understanding, identification of allies and experience of positive change delivering hope and a potent sense of agency on the one hand, awe at the scale and intricacies of the systems which shape the problems we wrestle with delivering a sense of hopelessness on the other. It might be daunting but we are part of it. As one of my co-learners brilliantly put it: ‘I am the system; we are the system’.

Oliver Standing is Director of Collective Voice, the national alliance of drug and alcohol treatment and recovery charities. He is responsible for its day to day leadership and delivery of its main activity – policy and advocacy work to help bring about an effective, evidence-based and person-centred support system for anyone in England with a drug or alcohol problem. Collective Voice also shares good practice and brings together networks across the sector.

Before this Oliver worked for Adfam (the national charity working to improve support for families affected by drug or alcohol use) for eight years, latterly as Director of Policy and Communications. He has a deep interest in systems change, having taken part in the School for Systems Change Basecamp for Health Leaders in 2021, with a particular focus on policy-making in complex environments and driving collaboration across organisational boundaries. https://twitter.com/OliverStanding

originally published at School of Systems Change

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Decentralized organizing: More collaboration, less hierarchy

From organisational governance to mobilising and sustaining grassroots movements, what is decentralised organising and how can this approach facilitate collective but efficient decision-making without management hierarchy?

Decentralised organising isn’t just about delegating tasks and responsibilities. It’s about transparency and openness, including how financial decisions are made and how labour is divided. This approach creates a great work ethic:

- Empowering members to do the work they care about, not just what they’re told to do

- Cultivating a culture of trust, collaboration and transparency

- Incentives are aligned because ownership is open to all

Sounds good? We recently caught up with Rich and Nati from Loomio while they were in London and discussed some useful decentralised organising approaches. Here are some changes you can easily implement to start working more collaboratively with less hierarchy:

Establishing “ground rules”

Norms are informal agreements about how group members should behave and work together, e.g. open, honest, inclusive. Boundaries are behaviours that we want to exclude, e.g. no mean feedback, exclusionary decision-making. Collectively, norms and boundaries can also be referred to “ground rules”.

Take time to listen to each member’s perspective. Then, as a group, decide on what your shared norms and boundaries will be. Finally, have this documented and accessible to all members and new members so that expectations are clear and transparent. This way everyone is bound by the same ground rules.

Communication norms

Open but efficient communication is a cornerstone of successful and strong relationships. It can be built by establishing communication norms and collectively agreeing on what communication tools to use for what job. For example:

- Realtime: like whatsapp chat: Informal and quick, it’s about right now.

- Asynchronous: Email or Loomio. More formal, organised around topic. Has a subject + context + invitation. Can take days or weeks.

- Static: Google Docs, Staff handbook, or FAQ. Very formal, usually with an explicit process for updating content

An understanding of when to use different communication tools avoids clogging up communication channels with unnecessary information. Finally, it is important to support members to learn how to use tools and remind each other gently to build habit.

Sharing is caring

Hierarchy habits such as having the same chair for team meetings can discourage other members to feel that they can bring ideas forward, participate in decision making, and take leadership. It is important to be intentional about the behaviours you want to bring to your organisation or network so that members trust each other and feel comfortable working together:

- Intentionally produce a culture of trust and belonging by sharing power, enabling lots of time for discussion, for natural leaders to be reminded to hold back and let others talk,

- Growing collaboration skills with practice through empathy, reflection and communication. It helps to have 5 mins reflection at the end of the meeting to ask people how they think it went – OR send out an anonymous reflection form just after the meeting to see how it performed against the organisational values.

- Distribute ‘care’ labour: make care work visible so that it can be fairly shared – this includes things like organising biscuits to setting the agenda.

Decentralised organising in practice: The Lambeth Portuguese Wellbeing Partnership

In this next section, we feature the Lambeth Portuguese Community Wellbeing Partnership (LPWP), a grassroots community network of over 40 local groups and community members. Bringing together organisations and people from across the health, social, charity and voluntary sectors to listen and work together, the LPWP is an exciting example of working in partnership through decentralised organising to help the Portuguese speaking community live healthier lives and to remove the barriers they face accessing health services. The partnership are keen to work towards adopting a decentralised organising approach and are on a continuous journey to work towards greater transparency and collaboration to create change.

Their successes and impact so far include

- A Breakfast / Homework Club run in conjunction with a Portuguese Café, a local school, educational charities and the NHS.

- A GP surgery and a voluntary sector organisation carrying out joint assessments of frail and vulnerable patients, with the voluntary community liaison officers providing care-coordination and links into social support.

- End of life and Latin American disability charities working together to modify advance care planning templates, empowering those at the end of life to make the decisions that are important to them.

- Culturally relevant patient leaflets, education videos and an NHS ‘Welcome Brochure’ in Portuguese, informing patients of their NHS rights and self-care options.

- A children’s charity working with scientists, to provide children from vulnerable backgrounds experiences working in science in universities.

The LPWP commissioned the Social Change Agency to support developing a strategic and decentralised organisation framework that will ensure that the partnership can play an active role in helping people with multiple long-term conditions live fulfilling lives for longer. It was a great pleasure to meet and interact with some of the organisations and individuals within this partnership, their passion and commitment to working together through values that include inclusivity and trust to improve the wellbeing of Portuguese speakers in Lambeth is truly inspiring!

If you want to focus was on moving towards flatter hierarchies, grassroots decision-making, and letting go of traditional hierarchies, then get in touch to find out how we can help.

The Social Change Agency is an expert team of strategy consultants, campaigners, communicators, and governance geeks. They’ve launched powerful movements, built innovative networks and led groundbreaking campaigns - their expertise spans every aspect of social change.

originally published at The Social Change Agency

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

6 Reasons Why Liberatory Leaders Need to Take Play Seriously

When was the last time you played, did something just because it was fun and felt good? Did you finish feeling enlivened, relaxed, energized, or something similar? Leadership Learning Community has been exploring the roles of fun and play in our activities. This exploration didn’t start out super intentional, but rather as a reaction to the pandopalypse we’ve all been living in. Over time LLC began discussing play in relation to our work, referring to aspects of our work as “playful” or describing meetings and convenings as “play spaces.” For us, this isn’t a cutesy communications strategy. As LLC began to turn our attention to play, we realized that play, when grounded in collective purpose and steeped in values, can be a liberatory act.

Here are six reasons why we believe play can help leaders embrace liberatory practice.

Fuel Ideation

- Play can be described as “something that’s imaginative, self-directed, intrinsically motivated and guided by rules that leave room for creativity.” By creating space for creativity and imagination, play helps to quiet the self-conscious, judgemental inner critic. This voice discourages deviations from the known norm and makes trying on new things feel too risky. Without that voice, perhaps there is room for a little bit of magic to invite in new possibilities. Taking a playful stance allows us to adopt a child-like or beginner's mind, and helps us to develop mental plasticity and adaptability while simultaneously reminding us that our options aren’t all pre-determined and that there is space for the not yet known. This opening of possibility is critical as liberatory transformative efforts are dreaming and imagining into being something that does not currently exist. To do that, we have to stretch our imagination muscles.

- Practice: Start the meeting with a playful check-in question like, “If you could go back in time (or to the future), who would you want to meet?” or pick a favorite zoom filter to start the meeting with. Check out more of our check-in questions here.

Nurture, Healing & Wellness

- Play is an effective way to manage stress and can be a tool of both self and collective care. Play helps us to be in the moment, similar to meditation. In contrast to oppressive practices, which are confining and restrictive, sapping our spiritual and figurative energy; the enlivening nature of playful activities may help to heal these wounds.

- Practice: Host meetings near a park, the ocean, or in nature. Take a walk. Find new analogies for the work we do.

Create New Models of Strategic Thinking

- Playing makes things real, during play we don’t just imitate we also imagine and embody (something). Trying on liberation in play spaces/playful ways allows us to feel the benefit of liberation in the moment while we are learning more than we currently know. This focus on liberation now means that during play liberation doesn’t just have to be a future goal. In addition, some studies suggest that play supports memory and thinking skills, so play may literally help us think our way to freedom.

- Practice: Do some creative writing. Some of us have and are taking a writing course with Dara Joyce Lurie. She shares a quote from Edward de Bono, “Rightness is what matters in vertical thinking. Richness is what matters in lateral thinking. Vertical thinking selects a pathway by excluding other pathways. Lateral thinking does not select but seeks to open up other pathways. With lateral thinking one generates as many alternative approaches as one can. With vertical thinking one is trying to select the best approach, but with lateral thinking one is generating different approaches for the sake of generating them.”

Expand Leadership Opportunities

- Because play utilizes “creative rules” that are distinct from the rules and restrictions of regular life, in play, there exists the opportunity, though not the requirement, to separate capacity from expertise. All of a sudden, players “can” do things even if they aren’t experts at said activity. So you can play at being a pilot without actually knowing how to fly a plane. In playful spaces more people can function as leaders, meaning more people can be actively involved in imagining liberatory practice into being.

- Practice: Acting and improvisation exercises like “Questions Only” where you act out a scene given to you with only questions.

Build Community:

- Play offers us the opportunity to connect. When we create safe play spaces there is little risk to engaging. People can show up with a less performative stance. BIPOC leaders frequently find themselves under a spotlight or a microscope. The labor of being forced to code-switch or deal with being othered is exhausting so I imagine that BIPOC leaders especially are eager for safe spaces to be themselves. Where showing up as one’s whole self is an invitation and a demand, and for the purpose of supporting the BIPOC leader not to be of utility to others. Often BIPOC leaders are told to show up as their full self because observing BIPOC leaders is good for an observer, not for the benefit of the BIPOC leader.

- Practice: Shorten the strategic side of the meeting, and incorporate the karaoke, fun, and games as part of the meeting, not just extra at the end.

An Invitation to Wholeness:

- By allowing us to focus on pleasure and fun rather than objectives and outputs, play encourages us to be more than what we can produce. Perhaps play is akin to rest in that way, and maybe we can view embracing the revolutionary possibility of play in the same way that we have begun to respect how rest can be resistance. This need for play spaces may prove to be especially important for BIPOC leaders given that kids of color are often adultified early, and deprived of the space to play freely. By recapturing play, as we have attempted to reclaim rest, we may enliven our work and find new paths toward liberation.

- Practice: Make space for play at every meeting whether it’s a check-in, the location, the activities, or the bonding event. Make play and joy part of your community agreements so they show up intentionally during your work.

Ericka Stallings is the Co-Executive Director of the Leadership Learning Community (LLC) a learning network of people who run, fund and study leadership development. LLC challenges traditional thinking about leadership and supports the development of models that are more inclusive, networked and collective. Prior to LLC, Ericka was the Deputy Director for Capacity Building and Strategic Initiatives at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD), supporting organizing and advocacy and leading ANHD’s community organizing capacity building work.

Nikki Dinh is the daughter of boat people refugees who instilled in her the importance of being in community. Though she grew up in a California county that was founded by the KKK, her family’s home was in an immigrant enclave. Her neighborhood taught her about resistance, resilience, joy and love.

originally published at Leadership Learning Community

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

by Ericka Stallings and Nikki Dinh, co-executive directors of Leadership Learning Community

A Future for All of Us

AN EXCERPT FROM RACE FORWARD'S REPORT ON PHASE 1 OF THE BUTTERFLY LAB FOR IMMIGRANT NARRATIVE STRATEGY

IN 2018, DURING THE HEIGHT OF THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION’S attacks on migrants, immigrants, and refugees, a landmark study warned pro-immigration forces that “attitudes towards immigrants and immigration are extremely complex: even those who appear to be pro-immigrant (who even think of themselves as pro-immigrant) are often very conflicted.”

A majority of Americans support the idea that migrants, immigrants, and refugees deserve to belong and thrive. Many recoiled from horrific images of family separation, violence against migrants at the border, and white nationalist violence against immigrants in cities like El Paso. Yet when the country locked down under the threat of the coronavirus and the Trump administration nearly shut down the entire immigration system, too few stood up to challenge these severe policies.

How does the pro-immigrant movement begin to confront such contradictions? To begin to answer this question, it might be better to look not to the tools of policy in the realm of traditional politics, but the tools of narrative in the realm of culture.

Cultural change precedes social change. Narrative drives policy. This is why we must be as strategic and rigorous in building narrative power as we are in building all other forms of power. Narrative is the space in which energies are activated to preserve a destructive system or build a better world for us all.

Right now, anti-immigrant forces continue to shape the dominant narratives around migrants, immigrants, and refugees, claiming that they are exploitable, expendable, criminal, and unworthy of equal treatment. These dominant narratives have fostered policies that terrorize migrants, immigrants, and refugees emotionally, economically, and physically. They protect a harmful status quo.

We are called instead to forge a new consensus. We must move a majority of people to imagine and act to create a world that does not yet exist. In order to make this world a reality, we need to orient ourselves toward the world we want to win, and make this future tangible and irresistible to a majority.

In this first phase of the Butterfly Lab for Immigrant Narrative Strategy, we hosted sixteen leaders to develop, test, and align narratives that meet our current political moment and advance our vision for the world we want to build. We supported their work with research,coaching, and funding. We were heartened by the many breakthroughs we made together.

Our work in the Butterfly Lab in this first phase affirms what we have known and gives us some directions to advance the movement towards more strategic alignment. We found:

• Nearly everyone believes immigrants deserve to belong and thrive.

• But many find it difficult to imagine an America in which that may be true.

• Core audiences respond well to all tested narratives, including those focused on shared humanity, compassion, dignity, and respect.

• But stretch audiences do not respond well to those aforementioned narratives. They do respond well to narratives of striving, responsibility, and liberty.

• Our narratives need to make sense of the past and present, and point toward immigration futures that are compelling to all.

Immigration remains the “third rail” of progressive politics. And yet, even in these discouraging times, we believe it is possible to win. When we look at the cultural transformations that other recent narrative movements—from “love is love” to #BlackLivesMatter—have made, we see pathways forward. Over a long period of time, many people built narrative infrastructures that could work in concert with policy infrastructures. When narrative power-building met the social moment, cultural inflection points turned policies previously thought unreasonable into ideas worthy of serious consideration. With immigration, we too must invest in narrative as key to winning power for migrants, immigrants, and refugees.

In this report, we share with you learnings, frameworks and tools, and insights into directions we can take to move forward together. Whether you are an advocate or artist, a long-time veteran of the culture wars or thinking about how to apply narrative or cultural strategy for the first time, this report is designed to work for you.

It is also designed to help you think and act at multiple scales—locally, regionally, or nationally—with rigor, alignment, and purpose. The best narrative strategy should foster a unity of intention with a diversity of voices, approaches, and methods. It should help people work together with a sense of alignment along different timelines and fronts. We want this report to be used to build skills, capacities, and networks within the movement, and, above all, to help all of us approach narrative strategically.

You can access the full report at Race Forward HERE or at Network Weaver HERE

You can also access a standalone version of the toolkit HERE

Race Forward catalyzes movement building for racial justice. In partnership with communities, organizations, and sectors, we build strategies to advance racial justice in our policies, institutions, and culture.

About the Butterfly Lab: Race Forward’s Butterfly Lab was launched in 2020 to build power for effective narratives that honor the humanity of migrants, refugees, and immigrants, and advance freedom and justice for all.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Getting to the Goods (and Beyond “Folded Arms” Syndrome) in Impact Networks

“Your generosity is more important than your perfection.”

Seth Godin

Over the past 20 years of working with a variety of social change networks, I have observed a common dynamic surface after the initial enthusiasm and launch phase. As happened recently with a place-based network about a year into its development (navigating COVID and political uprisings along the way), some members started to bang the “What have we actually done?” drum. Contextual crises notwithstanding, this is not an inappropriate or unhelpful question. As important as relationship and trust-building is, there can come a time when people want to know … “So what?” Sometimes this comes from what we might call more “results-oriented” people in the network. Or it may come from the more time-strapped and stressed, those from smaller organizations, or those who just genuinely don’t see the return on their investment. When this has come up, and people are either holding back (“folded arms”) or threatening to walk, I have witnessed and facilitated several different ways of moving through the real or perceived lack of progress.

- “If you want it, then you better put a ring around it” – In one instance, the convening team of a state-wide network essentially drew a line around all of the network participants and started claiming their successes as network successes. This might sound a bit shady, though it was not done in that spirit. By celebrating “your success as our success,” people felt appreciated and started to turn towards one another and see themselves as a bigger we. They didn’t have to wait to get to mass action. Smaller subsets having success counted.

- Get a quick win – In another state-wide network, fraught at the outset by folded arms despite the fact that people would regularly physically show up for meetings, a network coordinator seized upon a timely policy advocacy opportunity that surfaced, which resulted in a mass outpouring and a legislative win. Nothing sells like success. That early victory got people eager to see what else they might be able to accomplish and they settled in for some more relationship-building.

- Collect and share connection stories – We know that relationship-building is not just about the relationships. It can lead to new partnerships and projects. Often this happens at the start of a network, but is not tracked. We worked with another place-based network that intentionally set out to track the results of connections made in and through the network, and then shared these with the network as a whole. More about connection stories here.

- Highlight the unusual and adjacent conversations – What makes many of the networks we work with unique is that they bring together people who do not often work with each other. Highlighting this and also what emerges out of novel interactions across fields can make “just talking” into exciting explorations and engines of innovation. For a little inspiration on this front, see “Why the most interesting ideas happen at the borders between disciplines” from Steven Johnson at Adjacent Possible (!).

- Pump people up, individually and collectively – Let’s face it, in these times (and really all times), expressing genuine appreciation can go a long way. We work with a network convenor who does this wonderfully, tracking and celebrating people for their individual contributions outside of network gatherings, and constantly speaking to the power and potential of the collective. She just makes people feel good! This can make the proverbial “marathon, not a sprint” more enjoyable.

- Get a super weaver going – Having a really adept and energetic network weaver can make all the difference in the early stages of a network. We have seen the impact this can have when ample capacity is created to regularly check in with people, listen to them, make connections between different needs and offers in the system, and encourage people to share more with one another. When those exchanges start happening, the “there” there is often more apparent.

- Lift up the network champions – Generally there is a small group of people who really appreciate and lean into the value of the network from the get go (gratefully receiving and using resources that are shared, following up with new connections, testing out new ideas, leveraging the network as a platform), making it happen and not waiting for it. Observing this, capturing it, and sharing it with the network can help make the point that the network is what people make of it and give ideas for how to make this happen.

What have you done to successfully navigate impatience and intransigence in impact networks?

About the Author:

Much of Curtis Ogden's work with IISC entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food public health, education, and economic development systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Strengthening Social Connection and Opportunities in Rural Communities

This brief describes an unfolding learning journey intended to strengthen social connection, resident voice, and agency to address inequities in rural health and well-being. Along the way, we have come to realize the important lessons for each of our institutions and ways in which we are better off for having taken this approach to our work.

At St. David’s Foundation, we believe that realizing health equity to minimize the consequences of poverty and racism reflected in the social determinants of health is foundational in our work in Central Texas. Rural communities are dramatically under-represented in philanthropic investments nationwide and in Texas, and the Foundation’s own balance of investments skews toward initiatives that serve urban populations. When philanthropic dollars are invested in rural communities, they are typically directed to the few established nonprofits and local government entities that implement programs or provide services to residents. Community members, especially people experiencing vulnerability and isolation, are rarely asked what they need to improve their health and quality of life and how they may utilize the power inherent in their communities to contribute to those improvements. The most common observation from the philanthropic sector is that “these residents” are rarely poised to receive and control funds to work on the issues they believe are most important for the health and well-being of their own community. Listening and enabling capacity can change that.

Listening to our Rural Neighbors

After a sustained period of building deeper ties and stronger relationships in our rural communities surrounding Austin and Travis County, the Foundation learned that many of our rural neighbors felt disconnected from and ignored by the Foundation and local decisionmakers in their communities who decide how resources are prioritized and distributed to address community needs. Residents from the surrounding rural counties of Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays, and eastern Williamson County expressed an interest in working with the Foundation and their peers on priority concerns including youth, mental health and substance use and misuse, food insecurity, and affordable housing.

Community Capacity Building and Enabling as Rural Strategy

In partnership with The Strategy Group (TSG), a national consulting firm with expertise in catalyzing resident-led community networks focused on health and well-being, the Foundation invested in community capacity building (CCB) strategies to engage interested residents in working collaboratively on issues of importance to community members and enable their inherent power to participate in problem solving.

Informed by residents, the Foundation and TSG co-designed an approach that incorporated key community capacity building outcomes so that residents could develop their own solutions to pressing self-identified community health concerns. TSG also offered a process for the Foundation to build its own capacity to invest differently in rural communities— an approach that invested in network infrastructure, resident leadership development, nonprofit leadership to partner with and support community networks, and connected people experiencing vulnerability and lack of connection to opportunities for community development.

The Foundation’s rural strategy centered social impact networks (Plastrik et al 2014), network weaving (Holley 2012), and sustained community engagement to create an expanding, diverse, inclusive resident-led network focused on health and wellbeing -inequities often reinforced by historical and structural legacies of exclusion and privilege. Stuart (2014) notes, “this is one of those cases where a commitment to social justice is crucial. It is important to consider who is included in the “community” that is leading the process. Who is excluded from community leadership? Whose voices are missing from community debate? Whose interests are being served?”

And if the community is driving decisions about their own development, what does that mean for how the Foundation should be investing in community?

Centering Equity and Equitable Opportunity

As St. David’s Foundation has embraced and prioritized health equity, rural investments evolved to become more place-based and community-focused. How the Foundation showed up in the community (and how frequently), how grant opportunities were presented, and how funds were distributed when CCB was the overarching purpose changed the nature of the relationship between funder and community. In our rural work, the Foundation recognized that a portion of our rural investment needed to give the community control over decisions and resources to determine what resources were needed to spur or make lasting change.

Bringing it all Together in Central Texas

The community network approach in Central Texas prioritizes:

- Centering the voices and lived experiences of rural BIPOC residents (equitable opportunity);

- Seeding a network of interested resident leaders who have a deep understanding of their and their neighbors’ needs to direct their own community development work; creating new relationships; and offering new ways of working, thinking and leading in community; (i.e., social impact networks);

- Engaging and supporting local residents to organize themselves to work on projects that move the community from talking about problems to taking action on problems (i.e., self-organizing);

- Supporting residents who want to develop the leadership skills to engage other residents to work together in a resident-led network focused on health and wellbeing (i.e., network weavers); and

- Putting a pool of resources into the hands of those who have the lived experiences of health inequity, poverty, social isolation; are closest to community problems; and who want to work with their peers to improve community health and wellbeing from a solidarity stance.

What are Networks and Network Weavers?

Social impact networks (like the ones emerging in Central Texas) are constellations of people, organizations, and communities connected by a shared purpose to make change. In the Central Texas network, there is a high-level purpose to improve the health and wellbeing of residents in the region.

Network weavers are residents in the Foundation’s rural service area who have chosen to be a leader in the network; they are the “engines” of our regional network. Weavers strategically connect other residents, convene groups of interested residents, coordinate small projects aligned with resident interests and needs, and work to grow the network and the projects the network is interested in pursuing. Holley (2012) describes a network weaver as “someone who is aware of the networks around them and explicitly works to make them healthier. Network weavers do this by helping people identify their interests and challenges, connecting people strategically where there’s potential for mutual benefit, and serving as a catalyst for self-organizing groups.”

The Foundation provides operating support for TSG as well as funds to support network infrastructure (e.g., communications, evaluation, training, storytelling), stipends for weaver leaders, and shared gifting circles. To date, over 100 residents have been trained to be network weavers in Central Texas.

Building Community Leadership

The Foundation’s investment in community capacity building by catalyzing resident-led networks and training residents to become network weavers is designed to engage and support residents to contribute their time and talents (i.e., community leadership) to solve pressing self-determined health and wellbeing challenges in their own communities. Residents also participate in monthly peer assist sessions which enable real-time feedback and advice from peers as they practice their leadership skills.

Participatory Grantmaking

Using participatory grantmaking processes and resources, network weavers are supported to identify local problems and then work collaboratively with other residents to co-design and test solutions. Shared gifting emerged as an important participatory grantmaking tool to support weavers during the second year of project implementation. We asked ourselves: “how can a small pool of grant funds be used to foster connection across different communities and authentic collaboration, rather than competition?” Shared gifting allows residents to decide what the most urgent community needs are, rather than the Foundation, and then to grant dollars to community projects they wish to support. There are no required outcomes of the process other than what is determined by the participants during the shared gifting process.

From participant reports of the shared gifting process, we were excited to learn that a shift in control of grant funds from the Foundation to the group of network weavers (residents) created an environment of social connection, equity, encouragement and support, feelings of abundance, and community. The typical grantmaking experience of competition and scarcity often experienced by potential grantees when responding to competitive grant opportunities was not reported by participants. Instead, weavers were excited to make new connections with other weavers, hear about new projects happening in their community, extend offers of time, talent, and treasure to other weavers, and expressed pride to be able to support those projects with the resources they controlled.

Conclusion

Residents who have participated in network weaving and participatory grantmaking have shared a common experience of personal and professional transformation, social connection, empowerment, and awareness of new possibilities and promise for their communities. The Foundation’s experience of investing in rural communities and its people by creating opportunities for resident decision making about how resources should be directed to pressing issues in their communities has revealed new possibilities for grantmaking and use of our social capital to advance the health and wellbeing of rural residents in Central Texas. Further, the experience with weavers as grantmakers underscores the importance and urgency of integrating community voice consistently in the Foundation’s equity-driven journey.

Voices and Learnings

Network weavers were invited to share their thoughts on how weaving has influenced their personal and professional lives. The themes found in their comments were that network weaving:

- Offers both professional and personal value to persons.

- Provides a framework that is valuable to tackle complex community issues.

- Facilitates making connections that create change in the community.

- Allows the use of shared gifting as a unique learning, connecting, and growing experience.

- Fosters among network weavers a desire to build new skills and capacities to continue to strengthen their work within their own communities.

- Encourages persons who had existing networks to make those networks more effective, efficient, and stronger by implementing what they learned in the Network Weaving learning opportunity.

“Weaving has tremendous value as it has empowered me to create with others outside of my usual network, helping to expand my reach and capacity to support others.“

“Throughout the past few years, in a mid-COVID society, Network Weaving has proven to be a skill set and collective necessity to maintain community collaboration. As work-life has evolved and more individuals experience isolation, Network Weaving has made the ability to connect (in-person or virtual) a go-to process for me in my personal and work life.“

Krystal Grimes, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Ultimately, all of us have the same end goal of building a better community. We all are here for the same reason; we’re all doing this work because we have a passion for community building. And network weaving has really given us that opportunity.”

“It has given me a really clear framework for what I’m doing. It’s not something that lives in my brain. Now. it’s an actual process and an actual framework that I can utilize to share information.”

Elizabeth Marzec, 2021, Organizational Leader, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Helping the community that you live in, helps you, it helps your children and helps your grandchildren. So, I think that is the point in the future that weaving really impacts.”

Linda Quiroz, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Bringing leaders together, making community change, and having people who never thought of themselves as a leader know that they can all make a difference. I love that.”

Kathleen Moore, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Prior to network weaving, I had no idea how to get this passion, this idea realized . . . I’m trying to be involved in the community. But I needed direction. I needed ideas, I needed strategies. And so, when I was invited [to learn about network weaving], it gave me what really felt like a breath of fresh air, because I’m going to be around peers that can help me along the way. And then also for me to help others.”

Sonya Hosey, 2021, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“I think about the word power. And that power is shared. It doesn’t belong to one person or group . . . and I love that about network weaving,”

“I have watched the whole design of network weaving just open this road for people to speak and share and dream, and nothing is impossible”

Maureen Stanek, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

References

Holley, J. (2012). Network weaver handbook: A guide to transformational networks. Athens, OH: Network Weaving Publishing.

Moore, W. P., Klem, A.M., Holmes, C.L., Holley, J. and Houchen, C. (2016). Community innovation network framework: A model for reshaping community identity, The Foundation Review, 8(3). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1311.

Plastrik, P., Taylor, M., and Cleveland, J. (2014). Connecting to change the world: Harnessing the power of networks for social impact. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Stuart, G. (Apr 10, 2014). What is Community Capacity Building? Impact Initiative.

Abena Asante has over twenty years’ experience in philanthropy, public health, and the nonprofit sector. A senior program officer at St David’s Foundation, she leads efforts that catalyze community action around issues and opportunities that align with the Foundation’s firm commitment to achieve health equity.

Dr. William Moore is Principal at The Strategy Group, a Kansas City-based international consulting firm supporting nonprofits, foundations, and communities. Bill is a Senior Fellow at the Midwest Center for Nonprofit Leadership at the University of Missouri – Kansas City, Senior Associate for Rural Health at the Texas Health Institute, and is the rural health advisor to the St. David’s Foundation.

originally published at gih.org

A in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and studied at Sciences Po, Paris as an Erasmus scholar.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

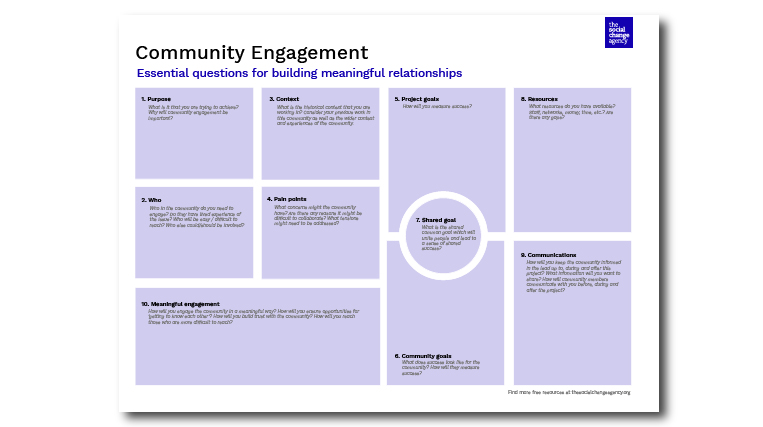

Community engagement: How to create meaningful connections in an age of distrust

Community engagement is a term applied in various contexts, often meaning different things to different audiences. It is sometimes used interchangeably with other concepts such as community outreach or community consultation. For the purpose of this article, we utilise the term community engagement to describe a process where local government, charities, and funders collaborate meaningfully with the communities that they serve.

The insights presented in the following text are informed by our experiences working with the above groups. We hope this article is particularly useful to those who are hoping to build stronger and better-informed relationships with their communities.

Community engagement

Community engagement is a key part of any project or programme that seeks to directly enhance the lives of the public. When providing services that affect people belonging to a defined area or group, building relationships within that community is a non-negotiable. Whether you’re a charity, funder or government authority, understanding what communities are thinking and feeling, and taking those thoughts and feelings seriously, is the only road to a legitimate and meaningful partnership.

What is community engagement?

Why is community engagement important?

How should I approach community engagement?

Download The Community Engagement Canvas [Free Resource]

What is community engagement?

Community engagement is all about supporting communities to take ownership of the resources that are available to them. This means taking an active role in creating partnerships between the institution that is providing those resources, such as a local council or charity, and the communities that will be receiving them. Grassroots, voluntary and faith organisations as well as mutual aid groups are deeply embedded in their communities and have a great understanding of local dynamics. This is what makes them such important partners for service providers.

In the simplest sense, community engagement is likely to involve connecting with community leaders and facilitating conversations about what they would like to see happen in their communities. This might look like restoring public spaces such as libraries or a community garden, engaging in discussions around improving housing standards or planning and programming a community event.

Why is community engagement important?

Over the last two decades, trust in ‘big’ institutions has been in a state of flux. Historical events such as Brexit and more recently COVID-19 have shifted our understanding of public life and how we relate to the institutions and organisations that shape it. The latest British Social Attitudes Survey reported that only 23% of people trust the government to put the needs of the nation before the interests of their party. So, how can those with institutional power begin to build back trust with the communities that they serve?

An approach gathering momentum in the US termed ‘earned legitimacy‘ puts forward the argument that it is the role of public institutions to build bridges with communities who have lost faith in their ability to serve. More specifically, it suggests that a public institutions’ legitimacy hangs directly on how much their community trusts them to act justly on their behalf.

Government might be a useful example to illustrate the meaning of earned legitimacy, but we believe that this approach is a solid one for any organisation that has the power, resource and will to engage communities in their activities. In short, it’s on you to put the work in.

How should I approach community engagement?

1. Get real about the role of history

When you work for a long-established organisation with substantial control over wealth and resource, people are likely to have pre-existing ideas about what you do and how you do it. Historically, many communities have been underserved and even harmed by powerful institutions. We see examples of this frequently in the news, whether it’s black individuals being more likely to be subject to stop and search or international charities such as Oxfam’s failure in preventing abuses of power. It makes sense that some communities are sceptical to work with those that have represented racism, mistreatment and harm to them in the past.

‘What are your concerns about this organisation and is there anything we can do to reassure you?’

The Centre for Public Impact recently released a report on how they went about restoring trust between Americans and local government by working with local communities in four different parts of the US. This involved “acknowledging past wrongs and showing a commitment to confront[ing] present-day […] issues.” The report highlights how important it is for historical tensions to be addressed with openness and honesty, especially in the early stages of relationship-building. This may involve asking community members questions such as ‘How do you feel about working with us?’ or ‘What are your concerns about this organisation and is there anything we can do to reassure you?’ before embarking on a shared venture.

2. Recognise that expertise exists within communities

The starting point for community engagement should almost always be that nobody understands what a community wants and needs better than the people belonging to the defined group. Big institutions often work with experts and consultants to problem solve and generate solutions. The Social Change Agency believe that the answers exist within communities and it’s really about creating safe spaces where those insights can be shared. If you are engaging communities in a consultation process, it’s worth considering that individuals should be paid for their time. They’re the real experts.

3. Getting to know each other is work too

With deadlines, budget restraints and the pressure to demonstrate outcomes, we often want to skip small talk and get right to the finished product. If you have the power to write ‘getting to know each other’ time into your project plan, this could really support relationship-building with your community and will almost definitely make things more efficient in the long run. Taking the time to visit the people you’re hoping to engage with and really understanding what motivates them can help to create the conditions for a durable partnership.

4. Communication, communication, communication

Whether it’s email, Slack, WhatsApp or Facebook, the way we interact often shifts depending on audience and urgency. This is no different when we are engaging with community networks. If barriers to communication emerge, it can drastically affect your relationship and slow down the pace of delivery. At the very beginning of your community engagement endeavour, ask community members how they would like to be contacted and what is most convenient for them. Make it as easy as possible to connect but create boundaries around how often and when is appropriate to communicate. This will give you a solid vehicle via which collaboration can flourish.

5. Defining success together

What success looks like to communities and what success looks like to funders, governments and charities are often two entirely things. Success to a local authority might be engaging 20 different community groups in a consultation process before opening a new digital community hub. Community members may visualise success as guaranteeing this space is free to use for certain age groups.

A way of define shared success might be creating an accessible and affordable digital hub designed by and for the community. It’s worth having a conversation about what both of your ambitions are for working together and creating a sense of shared purpose in your collaboration. Establishing a common goal is likely to keep you connected as you move through the logistics of delivery.

originally published at Social Change Agency

Maisie Palmer 's interests lie in social innovation, education, and supporting community-led movements. Prior to joining our consultancy team, she was National Programme Lead for Education at The Roots Programme where she designed and delivered an exchange programme tackling social division amongst British youth. Maisie founded Mxogyny an online and print publication for marginalised creatives. She has also worked for the Secretary of State for Scotland and the International Criminal Court. Maisie holds an MA in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and studied at Sciences Po, Paris as an Erasmus scholar.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

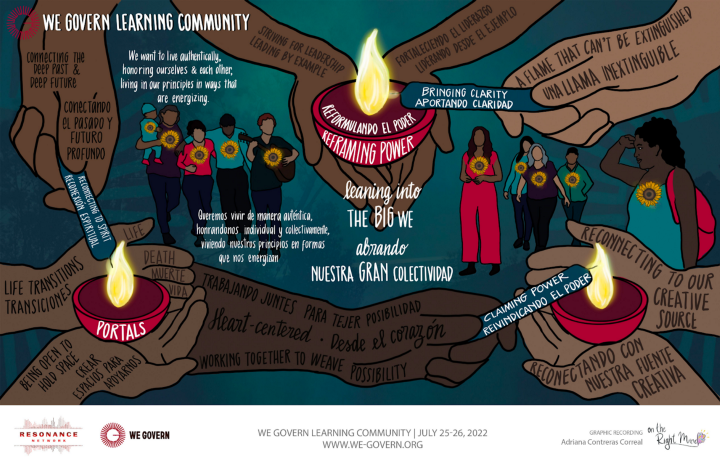

Reframing Power and Embracing What is Possible

Lighting the Candle of Liberatory Governance

As phase two of the WeGovern Learning Community winds to a close, participants gathered to reflect on their journey.

This community came together with a shared commitment to practice liberatory governance — and we did. Participants—including Resonance Network, who convened the learning community space but practiced as a participant team—reimagined what governance beyond dominant power structures could look like in our organizations, tribes, networks, and teams.

And what came through as we reflected on the experience was not only the transformations that took shape externally within these groups, but internally among participants as well.

Our choices add up to the world we’re building — and once you feel the power and possibility in choice making and community building from a place of liberation and care, you can’t turn back. We all felt that.

Our commitment to governance practice kindled a deeply felt sense of what is possible.

The process of embracing WeGovern—a set of governance principles rooted in mutual care, dignity, and thriving–in our own lives—helped each of us realize that we have more agency in the choices we make to live from our values than we realized.

Of course, the systems of control and domination we live within want us to believe that power exists outside of ourselves — but the opposite is true. Our choices add up to the world we’re building — and once you feel the power and possibility in choice making and community building from a place of liberation and care, you can’t turn back. We all felt that.

This practice became an affirmation that governance begins with each of us — in the choices we make each day to engage with ourselves, each other, our families, and our communities.

Bringing clarity

Each of us felt this sacred responsibility — an embodied knowing that developed in the practice. We described it as “a bell that can’t be un-rung” or similarly, “a flame that can’t be extinguished.” Once we felt that sense of agency in choice making — and began to witness the ripple effect of transformation in our communities — we couldn’t go back to business as usual.

But the future we are moving toward isn’t completely unknown to us — it lives in our lineage, in the memories of our ancestors, in the wisdom of the land that sustains us, and in the relationships we are building with one another.

Instead, we find ourselves choosing to move into the unknown — away from what has been familiar, and toward what feels whole. The future we are moving toward is unknown — it is unknown to the collective systems we live within that have shaped so much of our lives, profited from limiting our perceptions of possibility, and capitalized on dulling our sense of collective purpose. But the future we are moving toward isn’t completely unknown to us — it lives in our lineage, in the memories of our ancestors, in the wisdom of the land that sustains us, and in the relationships we are building with one another.

Reconnecting to spirit

The sacred responsibility of this way of worldbuilding, the connection to lineage and ancestral memory–bringing the wisdom of what was into what will become–is spirit work. It is work that requires tending to sustain it, but also sustains us. We seek spirit the same way sunflowers seek the sun.

We seek connection to spirit not just to ask for what we want, but to remind us of our humanity, our power, and our clarity in service to a higher purpose–a world where all beings can thrive. And that world is taking shape each day, in the relationships between us. If we are the candles that cannot be extinguished, our connection to spirit and purpose kindles the flame so that we can light other candles.

Claiming power

The flames we tend are a reminder of our power. The power that naturally comes from connection to source and purpose. The organic current of creative energy that flows when we’re in alignment with purpose and care. Despite the ways oppressive systems try to diminish our power, we are transforming ourselves, our communities, and our collective systems.

We claim our power when we see ourselves within the system–when we see and feel the way our agency, our choices can be used to change it. When our individual agency and power becomes collective. We claim our power when we refuse to be separate–from ourselves, from each other, and from the generations that came before and will come after us. When we accept the sacred responsibility of choosing the way we want to be, in alignment with the world we want to live in.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Weaving at Work

Over the past few years, I have been increasingly influenced by the concept of “weaving” — what for me means connecting people, ideas, and projects to foster more collaborative social change.

Weaving is a skill, a mindset, and a way of being. More art than science, it requires deep listening, being responsive to interests and needs, and “sensing” opportunities to bring people or projects together.

In many ways, it’s synonymous with other terms we use like facilitation, collaboration, networking, community building, relational leadership, etc.

I find weaving to be an incredibly powerful tool for fostering collaboration, decentralizing ownership, and sparking wide-scale impact.

But weaving often clashes with our traditional workplace habits and structures

One of the things I’ve been struggling with lately is how to make weaving a regular and consistent part of our team.

In the network I run, despite multiple attempts weaving still doesn’t show up in our to-do’s or our impact tracking system. When our time is limited (which is almost always), it quickly becomes a “nice to have”.

Often, we work in systems that are linear, logical, and task-based—from project management, to communication and coordination, to data analysis. Weaving is by nature more intuitive, emergent, and relationship-focused, and sometimes just doesn’t seem to fit.

As a result, weaving can be hard to integrate into our task lists, to coordinate across our team members, and to openly report on. And because our managers and supporters usually don’t see or experience it themselves, it can go unnoticed and misunderstood.

So how can weaving become a core activity that we regularly practice and valorize in our workplaces?

Last week, June Holley and I hosted a brainstorming session with the Weaving Lab around this question. Here are some of the ideas that came up:

- Weave everywhere, all the time — and explicitly state that you’re doing it. For example, in interviews you can cluster small groups of people who don’t know each other and tell them relationship building is a core goal of the interview. In team meetings you can leave time for storytelling and explain why this is important for building trust. In large group events you can integrate simple getting-to-know-you activities, and explain how connections are the core of any collaborative work.

- Explicitly write weaving in our daily task lists. Be they digital or analogue, try to make sure weaving is written down as a regularly-occurring task (e.g. weekly) for each team member. So even when a direct opportunity for weaving doesn’t show up to you, your job is to “find” one.

- Enable weaving through a light-touch database system. Keep an updated list of your team and community members’ needs, interests, gifts, skills, fields of work, engagement level, etc. Make it simple, so it’s easy to skim. And use your weekly task to actively “identify” new opportunities for weaving (don’t expect community members to do this themselves!). For example: find 3 people who haven’t met but you think would get along and introduce them to each other. Or, share a funding opportunity with 4 people working in a similar field of interest. By the way, CRM systems aren’t set up for this, so consider using a flexible tool like Asana or AirTable, or a network mapping tool like Kumu.

- Don’t weave alone or in isolation — weave with others. Mark “weaving opportunities” as a fixed item in your team meeting agenda. This helps you better coordinate to avoid overlap, be creative in finding weaving opportunities, and be accountable to making it happen, while also building a culture of weaving. One note:make sure your team has diverse weaving capacities so you can complement each other.

- Document and share weaving through simple and regular processes. Integrating weaving updates into your team meetings—e.g. “what relationships have we build this week” — so you capture and share things you may not have recalled. Have a simple “checklist” for immediately logging when weaving occurs (make it super easy, 15–30 seconds to open, log, and close). And do annual surveys and check-ins with your community to see what impact weaving has had over time.

- Help people whose support you need (e.g. bosses, funders) to “get” it. Use common concepts and metaphors that can make weaving easier to understand. Collect stories of weaving and share those with them. Invite them to to engage directly in weaving practices (e.g. a peer-to-peer problem-solving session where they can get support on a challenge they face and experience weaving in practice). And hold multiple meetings with them where you let them can ask you questions and get to know the practice better.

What would you add?

Brendon Johnson is a seasoned changemaker with a passion for strategies and models around networks, communities, participatory organizing, and collaborative action

Originally published at Medium

Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Applying regenerative practice to systems beyond place — some thoughts

By way of introduction: spiky fruit

It’s the first of October, and I’ve been writing this piece for over half a year! Yesterday this cactus caught my eye. The spiky leaves and the ripe fruit spoke to me of the necessity to take these unpolished thoughts and offer them up. If handled carefully and peeled, the juicy prickly pear can make a great salad. It’s painstaking and potentially irritating work. The flesh is not as flavorsome as other fruit, but it’s what grows and abounds here and now. So perhaps you can enjoy the thoughts that follow in that spirit!

Rising to the challenge

Our societies and our living planet are struggling to survive with the threat of climate change, mass extinction of species, depletion of the living resources of soil on all our continents — the list goes on. In the face of this regenerative work offers the hope of enabling the extraordinary capacities of living systems to adapt and create the conditions conducive to life.

There is an active community of regenerative practitioners supporting change-makers the world over to work from the principles of living systems in order to revive and evolve the places and the systems they are working with. Living systems are grounded in places, adapting to local conditions and contexts, evolving strategies to thrive in the myriad diversity of environments, from hot deep sea vents, to estuaries where sea and land intermingle, to cloud forests of the tropics, to green ‘deserts’ of grassland. The source of regenerative practice is found in the dynamic relationship of life and place, and the inevitable relationship of people to and within other living entities. People, human societies, are living systems, and as such we are deeply connected to the places we live and depend upon.

However, as human societies have evolved over the last few hundred years into a global civilization, and many of the challenges we face are playing out on the scale of the whole planet, regenerative practitioners are called to find ways to apply our living systems approaches to activities that seem disconnected from “place”. When we look to change international business supply chains, when we design digital services, when we think about what sustainability means for huge global retail corporations, how can we bring regenerative practice to bear? In an age where the shift to online working has been accelerated through the Covid-19 pandemic, and I write this from a co-working space in the south of France as part of a team with people across four continents, how can the potential of life-regenerating work step into and beyond hyper-local “place” as a contribution to a societal shift so needed this decade?

What follows are a few thoughts, deeply influenced by my work and dialogues with Regenesis, Future Stewards and other regenerative practitioners. These thoughts have formed as I apply this practice to the School of System Change, an international endeavour to support change-makers navigate the field and practice of systems change, growing their capacity to work with complexity and uncertainty, and to contribute to great shifts in business, civil society, government, communities and philanthropy.

Disconnected from place?

I deliberately speak of activities that seem disconnected from place. Our human capacity to understand ourselves as disconnected from nature, from living systems, from place, has been honed over several hundred years of Western mechanistic thinking. Those of us who have learnt to understand our world in this way continually develop constructs — both physical and conceptual — that reinforce this premise of separation or non-dependence on life. We build global digital platforms with remote-working teams. We manage supply chains from warehouse to container to truck to logistic platform to supermarket in a complicated chain through multiple built environments made of concrete, metal, tarmac. We speak of dematerialised banking, and have decoupled finance from the “real” economy. We manage agricultural production through sterile seeds and petrochemical fertilisers.

I have learnt to see how all of these activities are nested within the living systems of our planet. The people working behind their screens or their steering wheels are alive, they need food to nourish them that is alive too (or at least was recently!). Our businesses, communities and cities are complex living systems with the same needs and metabolic functions as a forest ecosystem: nourishment for energy, clean water, purification of waste, temperature control… The people and places impacted by “dematerialised” activities may be widespread and seeminging disconnected, however they are indubitably alive, and in many contexts in need of activating their regenerative potential to tackle increasingly difficult issues of physical and mental health, pollution, soil degradation, and adversity.

Pretending that a human activity has no grounding in living systems and places — because of its digital or global nature, because it involves commodities sourced via intermediaries and their warehouses — carries a high risk of creating harmful externalities to the living systems that are inextricably linked to these activities but remain invisible in our designs. This decoupling of our activities from the living systems we operate within perpetuates the deep-seated pattern that has led to the crises we are living into today, from climate change to the global pandemic.

Putting living systems back in the equation isn’t easy work, but it is possible, and deeply rewarding. Where might we start?

I am offering three sets of practices that can support a regenerative outlook, even when working with systems that seem disconnected with place:

- Seeing life in everything

- Working with specificity not generic outcomes

- Starting with the care we hold for our fellow living beings

Seeing life in everything

The first set of three practices are helping me develop my ability to see living entities — people, organisations, places — as alive.