SHIFTING A SYSTEM: The Reimagine Learning network and how to tackle persistent problems

[ap_spacing spacing_height="12px"]

Some problems are simply too big for any one organization. One solution: a network of like-minded leaders working toward a common goal. Reimagine Learning, taking on systemic education issues, offers a successful model.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

In an increasingly complex business and social environment, many are looking for collective solutions to big problems. Networks can address sprawling issues in ways that no individual organization can, working toward innovative solutions that are able to scale.

Fortunately, the collective capacity to address persistent problems is deepening in real and exciting ways. A set of tools, processes, and mindset shifts has emerged to help leaders align a set of diverse actors around a shared understanding of a problem and then create a coordinated plan of attack.1 This approach to large-scale problem-solving is a powerful way to catalyze progress.

Our full-length report, Shifting a system, presents a case study of how a group of leaders and their organizations can coalesce behind a shared vision for change.

The Reimagine Learning network came together to tackle big education issues, ultimately aggregating and deploying US$38 million in philanthropic capital. Over six years, members worked to create teaching and learning environments aimed at helping to unleash creativity and potential in all students, including those who have been historically underserved. The group—launched with 32 members, now grown to more than 700—helped build and scale organizational models that embed a focus on both social emotional learning and learner diversity, ultimately funding 25 organizations that collectively serve 7 million students nationwide.

The experience of Reimagine Learning’s members suggests lessons about effective steps that leaders might take in constructing a network:

- Map the landscape. Reframe the problem. To broaden the aperture of possibility, bring unlikely bedfellows to the table.

- Understand differences. Discover similarities. To shift the status quo, imagine the future you want to create.

- Deepen strategies. Learn by doing. To make collective progress, embrace the intellectual humility of uncertainty.

- Move from curiosity to action. To deepen organizational capacity, nurture individual curiosity.

- Grow the group. Increase impact. To understand network impact, accept a broader definition of measurable value.

- Assess the whole thing and why it matters. To know where to go, assess where you’ve been.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Seeking systemic solutions

In 2012, when Reimagine Learning began forming, the US education system showed serious signs of struggle, with less than 40 percent of K–12 students proficient in math or reading and 1 million dropping out of school every year.2 Meanwhile, 12 million school-aged people had experienced three or more adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction, and 21 percent of all school-aged people lived in poverty.3

Leaders in education had formed well over 100,000 education nonprofits, aiming to address some of the issues, but the scope was simply too broad for any one organization to have a significant impact. In addition, even as a growing body of research highlighted the importance of supporting diverse learners—including students dealing with poverty-related trauma—educators, researchers, and advocates for students with learning and attention issues felt excluded from the general education-reform conversation.4

The Reimagine Learning network was launched to empower groups focused on learning differences, social emotional learning, and trauma. Catalyzed by Boston-based venture philanthropy organization New Profit and US$38 million of funding, this diverse network of change agents aimed to support an approach to education based on a deep understanding of how students learn.

Reimagine Learning’s goal was audacious and desperately needed: to fundamentally reimagine how learning happens for children in this country and to offer a new vision of how to meet the needs of a set of learners typically underserved by the education system. It was a call to action that galvanized people and organizations across the country to participate in a collaborative process to craft a vision and in a strategy to shift a system.

This six-year initiative demanded a major reframe in thinking about the role of education and how to make it more effective. And changing the mindset or paradigm out of which a system arises is one of the most powerful leverage points in a system you can affect.5 But gaining a hard-won mindset shift is only the first step in a journey. In the case of Reimagine Learning, getting to that point took years, and it was only the beginning of the process to get to action on the ground that would drive outcomes for young people and families. What followed was a series of changes—within and among individuals and organizations, in classrooms and boardrooms, at the dinner table and on the floor of the US Senate—that reflected this reimagining, allowing the effort to come one step closer to unleashing the potential of all students.

Participants’ involvement in shaping Reimagine Learning’s vision and strategy prompted them to reshape their own organizations, which collectively serve 7 million students nationwide.6 At its core, engagement in the network succeeded in changing the mindsets of many of its participants, who in turn influenced practices in school districts across the country and created a deeper understanding of what supports a “whole child’s” learning in a classroom.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Stronger together

Obviously, not every organization—or organizational goal—is best served by developing and engaging in a network. It’s a mode of problem-solving that asks leaders to assume a network mindset and demonstrate a willingness to work with and through others.

Ultimately, working in a network requires the integration of three key dimensions: an understanding of human dynamics—the people you need to build solutions and make them stick; an ability to craft collective strategy—getting smart about the problem and developing a point of view and action plan; and developing the right network configuration—designing and weaving a different kind of structure to support a group as it forges its own path forward.

It is a way of working that defies command-and-control posturing, in which insights come from the collective—and connections among them—rather than experts. It’s a journey on which there are no short cuts, and it will try the patience of those tied to short-termism. Yet it is an approach to problem-solving that we hope continues to be tested and developed.

See our full-length report, Shifting a system—a case study developed by the Monitor Institute by Deloitte in collaboration with New Profit—for a full account of how Reimagine Learning’s members came together to accomplish real change.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Originally published 4/29/19 at Deloitte Insights by Anna Muoio and Kaitlin Terry Canver

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

The Transformative Power of Networks of Networks

Three Level Networks for Transformation

I’ve mentioned before that transformation or system shifting requires networks to be involved in networks of networks. This blog post will explain why every network needs to be part of and explicitly develop networks of networks to maximize their impact.

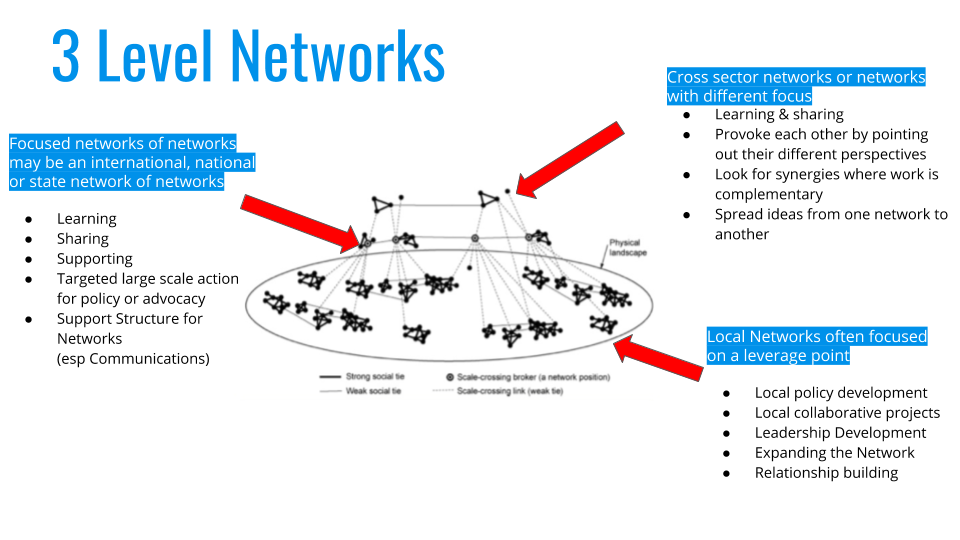

Networks need to be part of three types of networks, shown in the drawing below.

1. Local Networks

Local networks are networks formed in a particular locale, usually a city, town or in rural areas or a multi-county region.

Often local networks focus on a particular issue area, problem or alternative. Examples range from local food networks and local culture of health networks, to local climate change networks. Although a network may be catalyzed as part of a national effort (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s culture of health efforts, for example), it’s local roots in a set of specific local communities is critical for success.

Local networks are where small but concrete collaborative projects can be nurtured, and where residents can build new leadership skills as network weavers. Each local project is an opportunity to invite in new people and thus expand and diversify the network.

Local networks can also be very effective in advocacy and in policy work. For example, many local food policy councils are writing the food section of local sustainability plans (which city councils are approving with few or no changes).

Many local communities have informal networks, especially among nonprofits. Their staff probably know each other and may collaborate on the occasional project. But any community can become much more effective by making their local network more intentional.

This usually means:

- convening not only area nonprofits, but including government officials and agencies, businesses, and residents

- determining a purpose for the network which is essential to help focus collaborative efforts

- Identifying leverage points where change is more likely to occur

- forming work groups to collaborate around those leverage point

2. Focused Networks

Focused networks are networks, often national (though they may be state, multi-state or international), that focus on a particular issue, problem or alternative.

Often these are branded networks (have a specific name i.e. 350.org rather than environmental network) whose participants are individuals, organizations or local networks. So, for example, the Center for a Livable Future at Johns Hopkins has helped build a national network of local and state food policy councils. They have a lively listserv for sharing information and discussion, and frequent webinars and videoconferences.

Not all focused networks help foster local networks, but when they do, they gain access to lots of innovation and usually find that this strategy enables them to rapidly expand their national network. In addition, when national networks convene local networks, local networks can learn about the innovations happening in other communities and adapt those successes in their networks. So instead of simply focusing on individual local leaders, as many focused networks do, they could encourage and support the local leaders to form local networks. Center for a Livable Future did this by having a series of virtual sessions on how to create local food system networks.

Funders could amplify this catalytic and convening role for national networks by providing funds for Innovation Funds. Summer Matters, a network of summer programs for children, for example, set up an Innovation Fund to encourage their local members to form collaborative projects in their local community. When Innovation Fund projects are convened virtually, they can better capture breakouts and innovations to share with the larger network. In addition, the funded groups form a peer support network which generally last beyond the funded period.

I’d love to hear stories of focused networks that proactively helped local networks form...please share your experience in the comments below.

Focused networks are often able to mobilize large numbers of people and/or organizations to do advocacy or actions, or conduct policy initiatives. However, if they do these in a self-organizing fashion, i.e. encouraging people to work with others on posters for marches or for visits to legislators, and at the same time provide tools and encouragement to continue self-organizing when they return home, they can greatly increase their impact.

3. Networks With Other Networks

Networks can really benefit when they network with other networks. These types of networks help networks be transformative either through their differences or through their power of aggregation..

However, this type of network is most likely to be neglected. These networks can be one of three different kinds:

- networks of networks with a similar focus formed to create the numbers needed for effective large actions

- cross sector networks

- networks that are quite different in purpose but can be constructively provocative for each other and stretch everyone’s world views

Aggregated networks are composed of branded networks that are working on a similar focal area - for example environmental and climate change - who can work together, especially on large-scale actions and campaigns or on policy initiatives, to have much greater chance of serious impact than could result from a single network’s action.

Most of these networks are loosely linked to others like themselves but few have explicitly met to discuss ways they can share information or identify emergent opportunity areas where they might work together. Many aggregated networks are formed for marches, such as the 2014 climate change march in New York City. However, like this one which was orchestrated by a single organization (350.org), the network brought together by this march was short lived.

We strongly encourage national networks to begin reaching out to other related networks and meet as peers not just on joint marches and actions, but to understand the system they are trying to change, determine who is working on what, and figure out how they might have some protocols for sharing information and have convenings to share what each is learning.

This is something I’m particularly interested in working on, so if you are too, get in touch with me at juneholley at gmail.

Cross sector network of networks are when a network invites in or networks with entities or networks from different sectors. For example, a local food network might create a larger network that includes local policy council networks, local food businesses networks such as restaurant associations, farmers, and manufacturers, markets such as schools and hospitals, and government officials and agencies. Including participants from different sectors accelerates shifting of the food economy: the network can help markets and producers better connect, for example, to increase production of local food, or it can create food policy proposals that will be easily approved since a wide ranges of perspectives helped create them.

Another example of cross sector networks of networks are those that form around large landscapes, such as the Rocky Mountains, to develop joint policy and collaborative actions. They work hard to bring all the networks involved “around the table” -- loggers AND environmentalists, for example. Participants in such networks do not have to agree on much, only join together with subsets of the network on projects and sub-projects that serve their interests and priorities.

Networks of networks with different focal areas. This occurs when a network intentionally reaches out to a network with a different purpose or focal area to expand their understanding.

Leadership Learning Community (LLC) recently convened people from a number of different networks in Oakland California. During the gathering a racial justice network interacted with more traditional health organizations, and both benefited greatly from each other’s perspective. In St. Paul Minnesota, a network of public libraries began working with networks working to support homeless people. This resulted in some libraries becoming support stations for homeless individuals - installing showers, lockers and Internet access stations.

Another example is a set of networks who come together around common learning interests. For example, I work with the Resonance Network (working to create a world where all women and girls can thrive) and the WEB Network (well being and equity bridging network supported by RWJF). First the WEB Network met with Resonance to hear “lessons learned” from Resonance during their formation process. What things did they do successfully? What did they wish they had done sooner? Both networks are now sharing what they are learning as they develop Innovation Funds and facilitation pools. This network of networks is expanding as these networks query other networks on communications and governance systems.

4. In Conclusion

Networks of networks have huge potential. They encourage the kinds of aggregation and numbers that can result in successful campaigns and policy initiatives. They also can convene innovative projects from around the country (or world) to learn from each other, support each other and provoke each other to expand how they think about what they are working on.

Unfortunately, few of these types of networks of networks exist. Funders would find it very fruitful to invest in the explicit formation of networks of networks, as it could massively increase learning and impact as networks share innovations and aggregate their power.

In the free resource for this week is a diagram of networks of networks and a set of questions you can use to help your network think more explicitly about the networks of which it is a part.

Please share your stories about the type of network(s) you are involved in the comments below. Or, what type of network of network do you wish existed so you could be more effective?

Header Image by Evie Shaffer on Unsplash

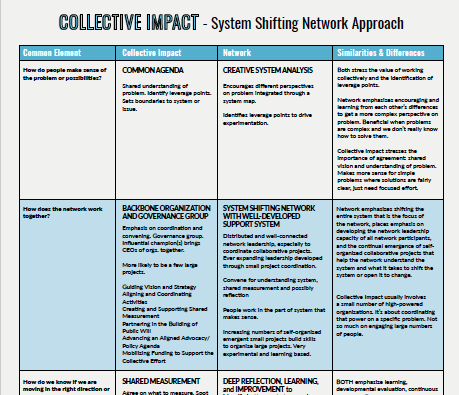

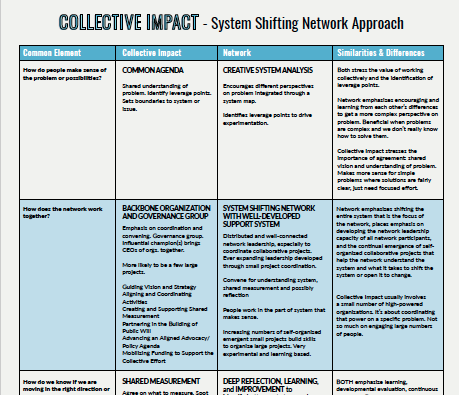

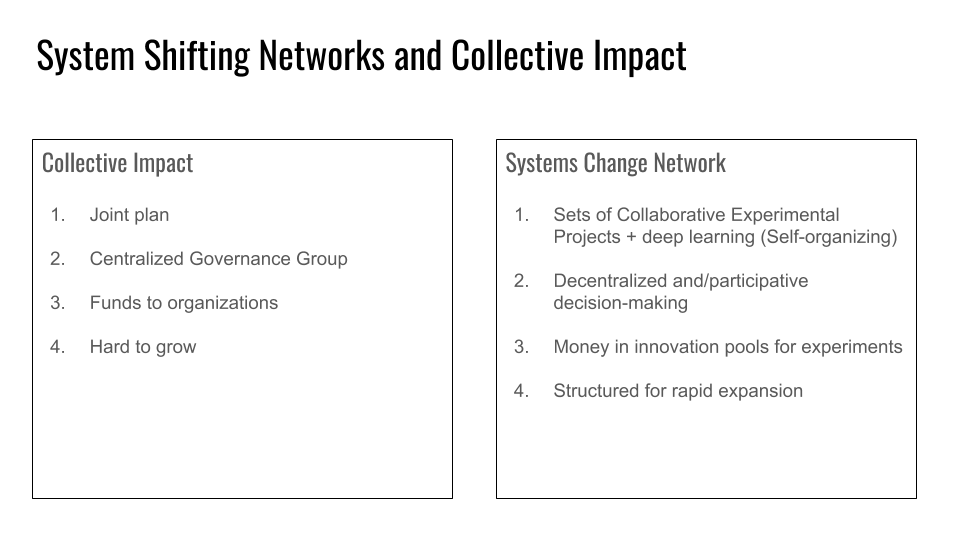

Collective Impact

People frequently ask “How do network approaches differ from Collective Impact? Actually, Collective Impact, with a few modifications, can be a system shifting network approach which can increase its long term impact by engaging many more people in change work.

If you are a Collective Impact initiative, you might want to share this chart with your partners and spend time deciding which network qualities you might easily incorporate into your efforts.

Collective Impact ~ System Shifting Network Approach

People frequently ask “How do network approaches differ from Collective Impact? Actually, Collective Impact, with a few modifications, can be a system shifting network approach which can increase its long term impact by engaging many more people in change work. Adding a more networked approach can also enable the Collective Impact effort to tackle more complex problems.

We have developed a chart that details each approach and then delineates the differences.

Collective Impact initiatives are quite different as a group and your Collective Impact initiative may not fit my rather simplistic description. Please let us know how your initiative works and whether it includes any network approaches.

If you are a Collective Impact initiative, you might want to share this chart with your partners and spend time deciding which network qualities you might easily incorporate into your efforts.

To summarize the chart:

We encourage you to comment on this post so we can hear about your thoughts and experience.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Transformative Networks Are Multiscalar

[ap_spacing spacing_height="30px"]

This is an excerpt from the Network Weaver Handbook. I'll be writing an update with my latest research and thinking on the topic in the coming weeks so stay tuned! - June Holley

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

How does transformation of our systems happen?

In the 1950s, researchers developed a model of the diffusion of innovation where, when influential individuals adopted an innovation, that practice or idea would spread rapidly among the rest of the population. In this model – still favored by many marketing strategists – all you had to do was to identify influential individuals, convince them that your product was superior, and their influence would ensure that many other people adopted your product. The adoption of the use of hybrid seed corn in the 1950s and the fad of hula hoops were touted as successful examples of this type of innovation diffusion.

"The critical question is whether an how social networks can help facilitate innovation to bridge the seemingly insurmountable chasms that separate local solutions from broad system transformation."

- Michele - Lee Monroe and Frances Westley

More recently, Duncan Watts, a researcher in the area of complex networks, refuted this simple approach to the diffusion of innovation. He showed that whether an idea or practice is spread by an influential person is highly probabilistic – sometimes spread happens and sometimes it does not. Spread depends much more on the kind of network surrounding the innovation than on the kind of individual advocating an innovation. For example, if networks bridge across clusters so that there is now a larger network, innovations can flow to a larger set of practitioners. Also, networks where people are working in many projects, each with somewhat different participants, are likely to see innovations spread quickly. When a useful innovation arises in one project, the individuals in that project are likely to tell all their other projects about the innovation.

"Scale the edge, not the core."

"Building on this, we have discovered that creating multiscalar networks – networks that cross levels or layers – are what turns innovation into widespread systemic transformation. We have identified specific patterns of 3 layers of interconnected networks that can bring about this transformative effect. People working in an issue or vision area need to make sure that they are part of all three if they want maximum impact.

- Level 1: Build local networks for experimentation

- Level 2: Build networks for scaling out so that local innovations can spread, inspire, and learn from others

- Level 3: Build networks for scaling up so infrastructure and policy to support innovations can be developed

LEVEL 1: Local Innovation Networks to experiment

"Scaling across happens when people create something locally and inspire others who carry the idea home and develop it in their own unique way."

-Margaret Wheatley, Walk Out Walk On

Chapter 10 described the process for creating a maximally innovative local network. However, there are two additional aspects of local networks that enable them to effectively link to networks at other scales:

- Development of an effective periphery for spreading ideas

- Expansion or spread of local networks for increased impact

The phrase, “Scale the edge, not the core,” describes the importance of developing an extensive periphery for your local network. Much of that periphery will be located outside of the local community. People in the periphery who help the local network be maximally innovative are:

- People in other communities around the world working in the same issue or vision area who can offer new ideas and practices

- People in other communities who are interested in what the local community is doing

- People who are connected to other disciplines or sectors and might have new insights or identify ways the two sectors could combine efforts

Another aspect of local innovation networks is that they encourage local groups to obtain a more sophisticated understanding of the entire system that their issue is embedded in and encourages them to work with others to address issues systematically. So, for example, a network working on prison reform might start to work with jobs programs and entrepreneurship organizations to develop better re-entry programs and, at the same time, work with a community development network on ending racism-related sentencing.

Many local food system networks have joined with artisan organizations and other local businesses to create healthy local economy initiatives. Other local food system networks have expanded their network to include those working on anti-obesity efforts. Transformation begins as projects increasing connect with projects working on other aspects of the system, thus amplifying their impact. Other fields (immigrant reform, criminal justice, reproductive rights, poverty, etc.) could all benefit from this type of local expansion of their networks.

Activity: Expanding your local innovation network

On chart paper or large whiteboard, have people in your network identify organizations and individuals they could add to their periphery to access new ideas. Then, using another color have them identify organizations that are interested in their local experimentation and with whom they might share what they are learning. Identify individuals in the local network who will seek out and/or stay in touch with each.

Using another color, identify local organizations from somewhat different fields but interested in some of the same problems or issues with which they might have discussions on how they could work together. Determine which are the highest priority. Who will reach out to them?

LEVEL 2: Scaling out networks

"Information can leap from group to group even when those groups seem to have nothing in common, because all they need in common is a single individual who is member of both groups and therefore has a bridging identity."

-Paul Hartzog

In the 20th century, many foundations funded efforts to replicate best practices. We know now that replication is an inadequate concept for the complexity of social problems we are working with for three reasons:

- Most projects need to be adapted to each specific community to be fully effective.

- Most projects can still be improved and so shouldn’t be replicated slavishly.

- Specific projects are still only one piece of a very complex problem or system and without integrating a number of system elements at the same time project success is likely to be limited.

Still, there is a lot of great experimentation happening in communities. For other communities to benefit from this requires a scaling out network. A scaling out network has four different aspects

- Support the spread of innovations

- Develop systems for determining which local efforts are worth scaling

- Support learning clusters of organizations working on similar strategies

- Support rhizomatic acceleration: research, venues, and leadership for scaling out

1. Scaling out by supporting spread

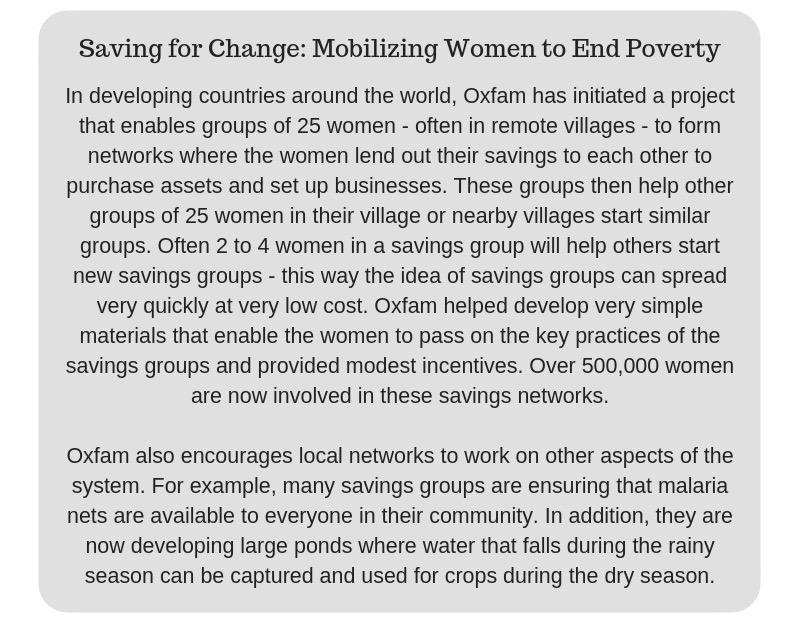

People in local networks need to be encouraged to share information about their innovations wherever they go. Funders need to provide incentives for successful innovative projects to coach other communities as they adapt that innovation (see the Saving for Change example below). Funders might have grantees suggest groups/networks they want to learn from, then help these identified innovators set up training sessions, site visits, or coaching.

Actually much informal sharing is already occurring, and it would be valuable to identify groups or individuals who have been very successful at informal sharing and document their methods and practices through case studies.

One of the best ways for people to learn about innovations is through stories about those innovations. The success of the RE-AMP case study by the Monitor Institute shows that there is a huge need and market for high-quality case studies. In fact, it would be great to have web sites where sets of case studies were collected, along with notes from conversations people had with each project so that a deeper and more complex perspective is available. People need to be able to take a “deeper dive” into the case study by asking questions of those involved in the innovative project or network. If such sites also had discussion forums, then we would be able to easily see which projects appeared to be attracting a lot of attention and funders could direct more resources to those innovators

2. Scaling Out By Developing a System for Identifying Projects for Scaling

Not all projects are worth scaling. How can projects be evaluated to help others determine whether they are effective? Initially, promising projects may not show clear outcomes but will have deeply embedded processes for reflection and learning that will enable them to continue modifying their approach until it produces results.

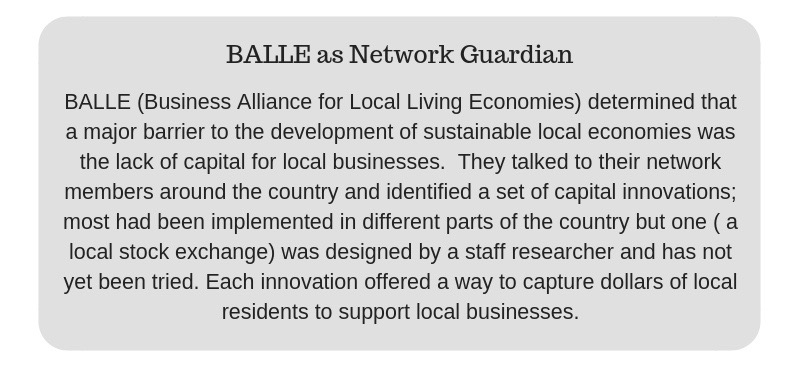

We need Network Guardians who are exploring issue areas at a meta-level, identifying projects that are tackling similar problems but using different approaches and noticing those projects that, in addition to showing early promise, appear to have a lot of energy and attraction.

The United Nations (cited in Critical Choices by Reinicke and Deng) calls this role a network entrepreneur. A network entrepreneur identifies niches where conditions are right for launching new global public policy networks and takes steps to initiate formation of a new network. Foundations and national networks could also help identify areas where scaling could be most beneficial. BALLE is an example of a national network that is identifying a variety of innovations that can fill the need for local access to local capital for local businesses.

3. Scaling Out Through National Learning Clusters

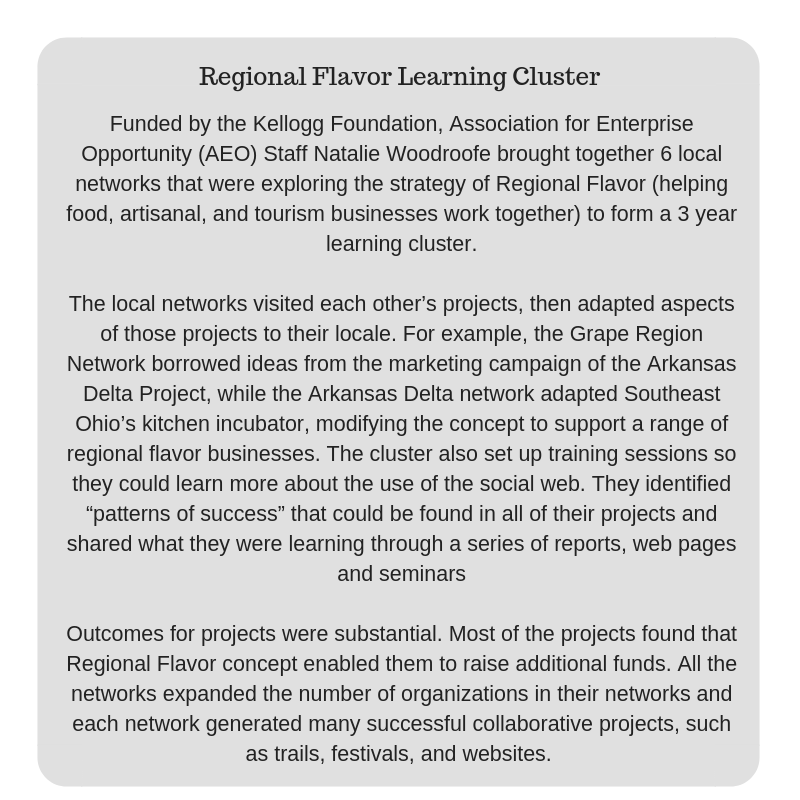

Learning clusters are one of the most underused and underfunded strategies for scaling projects. They are the second level in a multi\scalar network and critical for transformation. A learning cluster is a set of local network projects from different communities whose participants are brought together regularly (virtually and/or face-to-face) to share about strategies they have developed, build skills, and learn from each other. It is through intensive reflection by these initiatives that key leverage points for system change can be identified for an entire issue area.

Clusters can be composed of innovative network projects that are already underway or of local networks just embarking on a strategy (or, ideally, mixtures of both). In most cases, each project will be unique: variations among the strategies, in fact, are encouraged so that participants can continually learn from each other.

Three critical ingredients of learning clusters are:

- Highly skilled facilitation

- Attention to building deep network relationships among the participants

- Diverse participants from each participating local network (different types of organizations, individuals of different ages and backgrounds)

In learning clusters, projects are introduced to the innovations of other groups, and at the same time, the cluster as a whole looks for the critical elements among all their projects that lead to success. Clusters can provide peer assists (sessions where one project outlines a challenge and the other projects ask questions, give ideas and advice, and share information about resources). Each local group also gets assistance from the rest of the cluster as they adapt model projects from other cluster members to their particular locale. The entire group also provides support for each local project as it continually improves and refines its strategy.

Many learning clusters that have been set up by funders have not been successful because the local projects have not been the initiators of the convenings and have not been able to have a say in the selection of their learning partners. Learning clusters take surprisingly few resources to operate, but dissemination of findings to larger groups in the field and handbooks that capture the cluster’s recommendations on implementation both need to be part of the overall project.

Activity: Create A Learning Cluster

- Identify 6 to 12 organizations working in your issue area that you would like to learn more about.

- Have sets of twosies in your network, select an organization each to call and interview.

- Identify the ones that are most innovative. Find out if they would be interested in being part of a learning network.

- Identify a source of funds to support coordination of the learning clusters.

4. Scaling out by supporting Rhizomatic Acceleration: Research, venues, and leadership for continued scaling out:

The concept of rhizomatic acceleration is key to successful scaling out. When we study a ginger rhizome we learn that every bud of ginger has the nutrients to generate and support many other buds. As a result, ginger rhizomes can expand rapidly without any central authority (see photograph below).

How do we implement a rhizomatic approach?

- We ensure that all Network Weavers learn how to help others become Network Weavers.

- We make sure that individuals who are part of collaborative projects are made aware of the skills, processes, and platforms that are being used in that project, and are encouraged to use these in other projects of which they are a part.

- We make sure that network participants have many platforms and venues for sharing what they are doing in ways that others can adapt their innovations.

In addition, research teams (including practitioner and professional researchers) using a developmental evaluation approach need to be embedded in learning clusters from the start so that they can record what is happening transparently and as the learning cluster is unfolding. Developmental evaluation uses a complexity lens to understand what is being developed through innovative engagement.

By sharing information and insights as the learning cluster progresses, other local networks can be adapting what is learned in their locale even before the learning cluster has concluded. Webinars, gatherings that piggyback on conferences, and interactive websites – all can become venues for sharing out what is learned in the clusters.

In addition, participants in the first learning cluster could then become coaches and trainers in a second, larger learning cluster. In this way, learning clusters become rhizomatic accelerators to the extent that the initial participants become skilled at and willing to share what they have learned with other local networks.

Like ginger, where every node has the nutrients to support the budding off of many other nodules, learning cluster participants need to be encouraged and incentivized to help many others adapt their strategies (see Michael Quinn Patton’s Developmental Evaluation

[ap_spacing spacing_height="40px"]

LEVEL 3: Scaling Up

Transformation is unlikely to occur simply by having many communities adopt innovations. Not enough communities will find out about the innovation, not enough resources will be available even for those communities that do want to adopt innovation, and not enough connections among the innovations will occur for a tipping point to be reached. In addition to scaling out innovations, scaling up mechanisms need to be set in place.

Scaling up is the use of policy, platforms, strategy, and meta-networks to accelerate the spread of innovation. Scaling up has typically been accomplished by control-based mechanisms. Often corporations scale up by creating franchises (think McDonalds) where each local fast food restaurant is identical to every other unit – with all units controlled by a central office. This method of scaling up can produce rapid growth and substantial profits, but has resulted in many unintended consequences such as our current obesity epidemic with its horrific impact on quality of life and skyrocketing medical costs.

Another example is the No Child Left Behind legislation which mandated a system of testing for school children and led to “teaching for the test.” This policy required all schools to operate in this way and is an example of scaling up through control and homogeneity. The problem with this path to scaling up is that mandated policies don’t always accomplish their intended goals – as has recently been shown by the flat test scores for all grades. When this happens, our entire society suffers. “One size fits all” policies are seldom successful for issues as complex as education, since students and their communities vary so greatly that a single policy is unlikely to work everywhere.

Network systems offer a healthier and more useful model for scaling up, especially in situations where we are grappling with complex problems and systems: Regional or national meta-networks. A meta-network is a network of local or regional networks. Such networks enable rapid scaling up through the use of:

- System analysis for identification of leverage points

- Network Guardians

- Clustering into working groups or action groups to focus on leverage points

- Pooled funds

- Communication platforms

- Policy networks

The time is right for the formation of more intentional meta-networks for many issue areas. We now have enough experience with networks so that we can create structures that are likely to succeed, and the potential to increase impact is great.

Support for meta-networks

Scaling up is best accomplished through regional, national or international meta-networks that focus on a particular issue, problem, or system development area. Meta-networks can either be formally organized, as in the case of RE-AMP, or informally organized, as is the national network focused on supporting local food systems.

Informal Meta-Networks

In an informal meta-network, an organization or set of organizations playing the Network Guardian role identify innovations, convene learning clusters around those innovations and access resources for organizations/local networks in the clusters, and then share out the learnings generated by the cluster. They set up funding pools to support the expanding numbers of local networks implementing this innovation and connect sets of learning clusters, each working on different aspects of the system, so that the entire system begins to shift.

As learning clusters unfold, they identify key system elements for success of that strategy and will come up against barriers that will need to be addressed. Many of these elements would be better implemented by a regional or national program requiring new policy to be enacted. An informal meta-network encourages the formation of policy networks to move support for innovations from foundations to government.

For example, the local PLAN networks, described below, discovered that to fully support people with disabilities, they needed to work together to develop a national program that enabled these individuals to save money for a home, education, or a business (without jeopardizing benefits). This required policy networks to be formed to set in place the necessary legislation.

https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss1/art5/

Formal meta-networks networks

More formally organized networks such as RE-AMP set up networks with more explicit structures to help organize work. They have membership and formal structures – such as the Working Groups that RE-AMP set up – to organize the work. They have a set of platforms and venues for sharing information, from an interactive website to regular Working Group calls.