Power dynamics: A systemic inquiry

Why this article? Purpose and position

The word power keeps popping up wherever I turn. Through my ten years of doing my doctorate action research it was all over my notes and reflections. I kept pushing it out of what I was writing about and feeling scared to even go there as if the power of it itself was too much to face or to look at, as if it was just too complex and unknown. In the end I could not ignore the question and did reflect on what it meant for the work I had been doing. I concluded that the field of systems change did need to really integrate it more into its work. Fast forward a couple of years and the question kept on slapping me in the face, not literally but in the questioning of who you choose to facilitate a session, how you frame the work, make decisions and so forth — saying to me — come one you said it was important to what the hell are you doing about it!

This article therefore is trying to pull together some of the thread of the last four or five years of looking at the journey so far and what I have learnt. I have put off publishing this for eighteen months as if the final answer or way to present it will come, but that I also realise is a putting off — so here is some of the messy journey of stumbling around in the dark.

This article there has a few elements to it.

- Firstly how the issue of power relates to the systemic sustainability challenges we are facing — from climate change, deep inequalities that through the mirror that is our time in Covid has been seen even more acutely and how we might see the way they interrelate and are part of the same issues.

- Secondly exploring the concept of power and how it relates to systems change;

- Thirdly, looking at some of the insights about what makes up the dynamics of power, that are based in both our histories, and wider context as well as how that manifests in us individually and needs work all levels;

- Finally starting to explore some framings of the strategies we might take to work with power.

I am trying to explore this topic from a systemic perspective, by which I mean exploring the dynamics and deeper rooted mental models that affect them and how they play out in the world. In a previous article I explored the multi-dimensional elements of power which I will not repeat here.

I also want to acknowledge that I am a white woman born and living in the UK, I am middle class, went to a private school and have a postgraduate education. I am a Director of a charity and have a comfortable life. I have a huge amount of privilege, rank or social and psychological power. Over the last couple of years I have realised how much of this I still need to understand and do. I am still on a massive journey to explore what this means for me, my work and those I work with and most importantly how we best act on this exploration. I acknowledge that this writing in and of itself addresses the issue through my own lens of knowledge and privilege, intellectualising it, exploring it through tools and approaches that I use. And yet this is the only way I know how to unravel what I have been experiencing and the challenges that we see. I am trying to live life through inquiry, to explore what is emerging in front of me, to actively lean into what is needed, to learn from the experiences, to read and learn from ideas that are out there and to ask myself how might we enact these in practice, for myself, for the work that we do and for the world.

So I invite you readers to enter into this journey of exploring with me and am interested in your own reflections and feedback.

Why power is a systemic challenge; where does it show up and why is it a problem?

There might be many ways to understand this dynamic, we could start with questions of poverty, inequality and all social and environmental challenges. For example exploring the issues of climate justice demonstrates and shows the effects of our current frame of power. The causes of climate change have predominantly been created by those who have used and burnt carbon for their accumulation of wealth and the improvement of their lives. This meant that they drove their dominance in the global economy, from the industrial revolution to the perpetuation of colonialism. Whilst the effects of climate breakdown are being more acutely felt where the most vulnerable live, whose development and ways of life have been hampered and repressed by power dynamics in the past. It raises questions about who has and is benefiting, where is the burden and how can we move to a more equitable and fair world? How might we transition is a way that is just and fair (a just transition)?

At the heart of these issues is dominance — of one society, nation, peoples — where their policies and practices acquire control over another — through literal means — from slavery, use of resources, exploitation, occupying land. It starts from a place of difference, but is acted on from a sense of superiority, exemplified through racism and other oppressive behaviour across all forms of intersection.

The current exploitation of our planet and people are manifest from power dynamics that have been perpetuated and continue to be so in all our systems. Many of the historical drivers of our ecological unsustainability — of extraction, consumption, capitalism — are the other side of the coin of the issues of colonialism, white supremacy, racism. Understanding power therefore might help unlock how we might transition to a world that is not only sustainable but just and regenerative that is has the capacity to keep distributing resources in a fair way. We in the sustainability field can no longer ignore these issues.

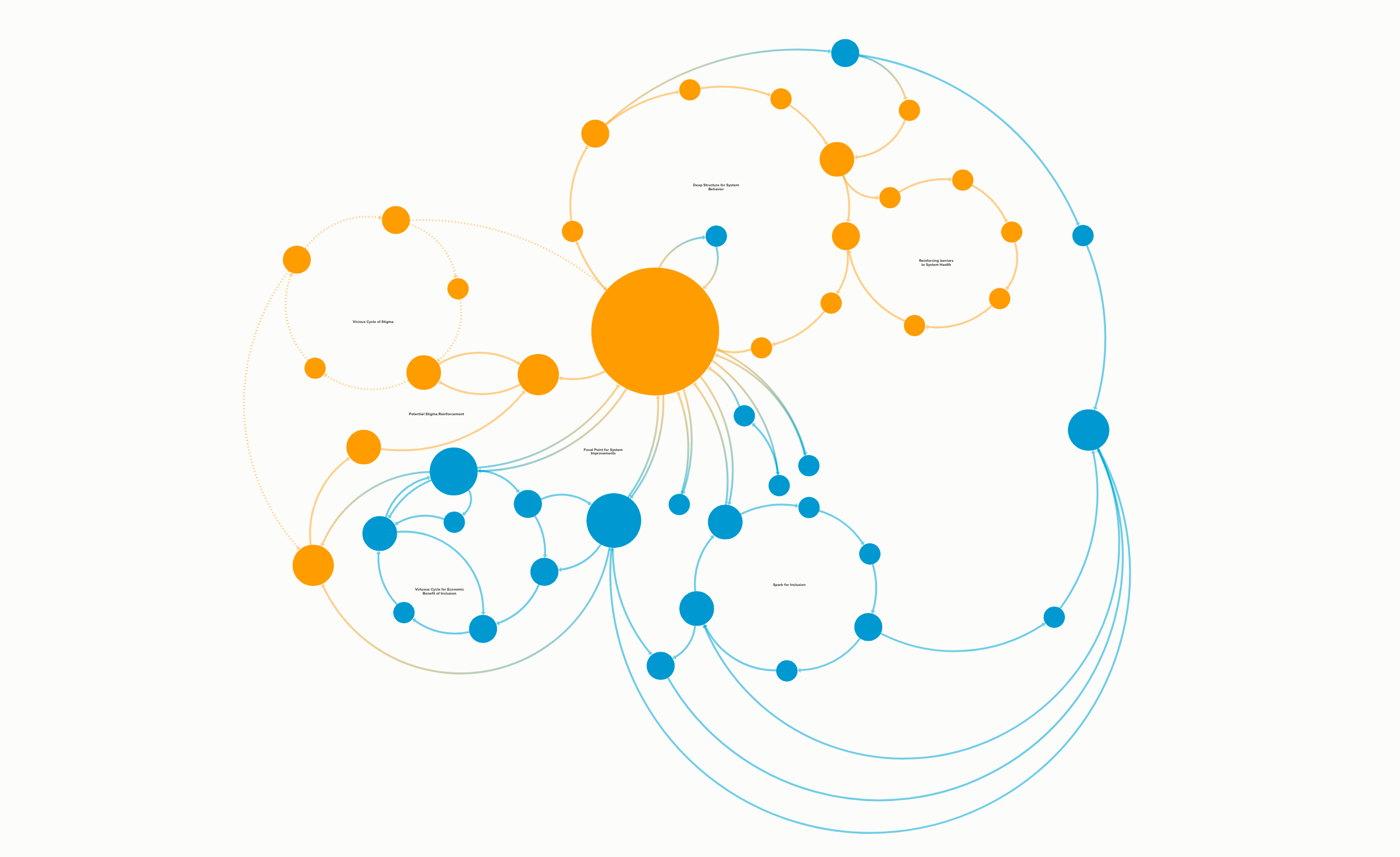

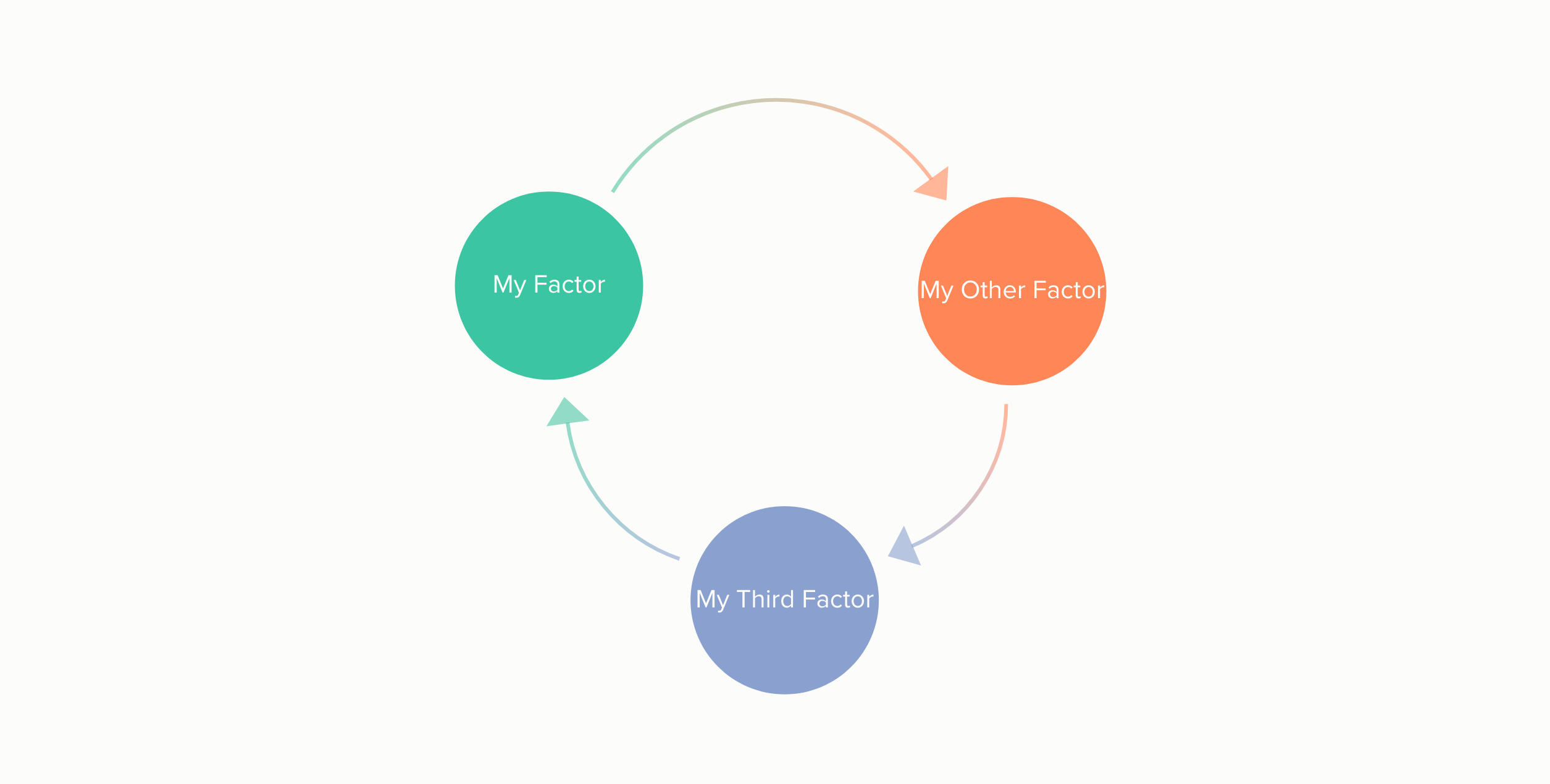

This diagram seeks to show how these different ideas and processes relate, how they are all part of the same dynamic. There are historical drivers and trends that have created the current world, a way to frame old power (which I will get to shortly). These manifest in issues that we see today in the world such as racism, under which are structural issues of inequality and privilege. I am proposing that these are all part of deeper power dynamics (that are informed by our perspectives). We are looking to understand how we transition to a future that is equitable and just and has power dynamics (new power) that are fluid, plural and understand life as a process.

How might we understand the concept of power?

Power is a contested term. The way we often use the word it assumes that it is about the power one thing has over another, be it explicit, or covert or unseen.

This first framing of power places it as a process of othering, by which we make others not the same as us, the noticing of difference and in the same breath we place value judgements of who is better, what is better and who has more power than others. This in turn starts to become embedded in our structures and our consciousness, so that structural racism or white supremacy exist.

Power as such though is simply the energy exchange between two things and so a second framing — I would argue a systemic one — starts to look at power through the eyes of our relationships, through the web of societies’ capillaries — that permeate the fabric of our existence. As such it also can be a motivator for what we do and how we do things, and has such power lies within us and can give us a sense of agency to change ourselves and things around us.

“We have the power over our own story” (Rushdie, 1991)

Power as such is not a static concept, it changes, not just who has it but also how we understand it through the course of history. Power operates within a perspective, worldview or paradigm. How we see power affects how we act with, on or from power. So it is vitally important to understand the position and perspective that we are coming from in order to understand power. For this article I will only use two — that of the current or old power of dominance and power over and that of the emerging new power — one that sees it more as the relational systemic flow.

How do we transition from a dynamic between us, now embedded in our structures, from one that has certain people, groups over others and which results in great exploitation of resources to one where we are living with just, fluid, plural, diverse relationships and where people have the sense of agency to also author their own lives?

Power and systems change

If we define systems change as the emergence of a new pattern of organising and power as a relational dynamic not a given state; then changing systems is all about also shifting power dynamics. Then in order to change systems and power dynamics we need to change the nature of our relationships and our ways of relating. As started to describe above, if we are to address issues of inequality, climate change, racism and all forms of social and environmental issues then addressing power dynamics is central to them all.

The current power model — or the pattern of how the system is structured is through coercive hierarchy and structures that are based in dominance, of power over and the relational dynamics we need to move towards is one that is systemic — by that I mean a way of living that recognises that life is change that we live and work in dynamics and fluidity whilst also recognising that this needs to be done justly.

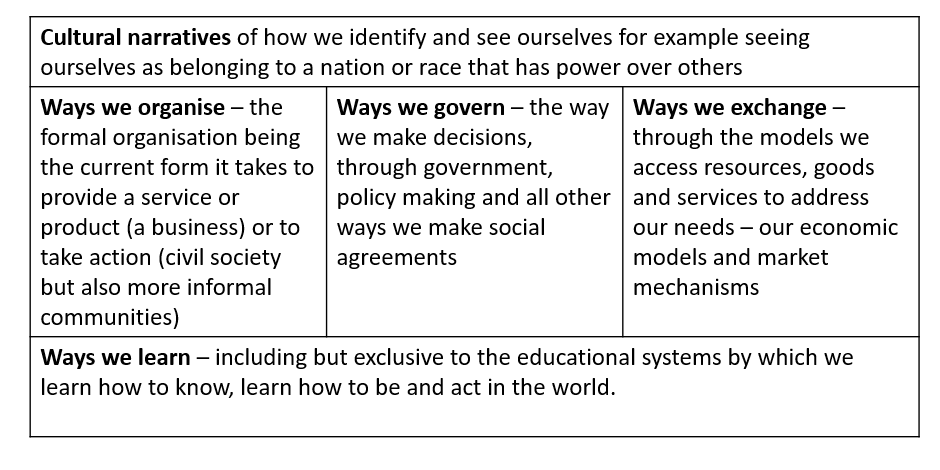

There are many ways we relate in society, where we have created societal structures around — each of which might be a route into addressing power dynamics. In society some of these foundational structures are:

[A note — not all power over is exploitative, for example in many hierarchical organisations, however if we want to address power that is then we also need to model what new relationships of power look like, so as to offer the potential for more healthy and flourishing relationships.]

What questions does it raise?

If I am saying power is an underlying dynamic and my overall inquiry question is — How might we cultivate systemic change? Then the question(s) relating to this exploration might be:

How might we transform society, its power dynamics, from the power over model that permeates today to a just form of relating and organising that is systemic?

- How might we change the nature of our relationships?

- How do we cultivate and be in relationship?

- Who do we work with and how?

What does this mean for us personally? In the projects that we do? What does it mean at how we transform society?

Insights in to what affects power dynamics

After exploring power as an idea and more importantly in practice over the last few years here are some insights into the dynamics of power from these experiences.

Although power is relational, we as individuals also have different positions in the web of social relationships. Having an awareness of your privilege and positionality and therefore any assumptions and bias you bring to any given situation is therefore critical to understanding power.

As we grow in relationships we do not grow straight and perfect. Different experiences and traumas, where unfair use of physical, psychological or social power has been used against you (Mindell, 2014), in our past determine how we grow from the inside out. These traumas are like knots or different shapes that develop in a tree that will continue to determine how it will grow and relate to others. These might be developed from how we are parented to the culture and society we grow within. This inner world, our psychology, plays out in our relationships and therefore can (re)create power dynamics that can perpetuate harm or injustices.

Due to our different awareness's, positions and life experiences we are all on different journeys of both understanding but also being impacted by dynamics of power. I have used the metaphor of yoga to help exemplify this. When we start doing yoga we have only a certain amount of flexibility, we are only so open. The way yoga is practiced is you stretch and move to the edge of what you can do, push in slightly but not too far and then relax, you transcend and integrate. You keep practicing and over time you open up to new movements and ways of doing things. This is the same for our addressing power, everyone has different levels of fluidity, openness, flexibility and ability to deal with these questions. This does not mean we cannot go on a more intensive yoga retreat or practice daily to get better practitioners.

Understanding our position and traumas requires inner work, that is to say working on the things that activate us or trigger us — that is something that might cause us to feel emotional not by the current experience but because it takes you back to something else in your past — that stop or hinders us from moving forward on our journey. Using the yoga metaphor again, if we had a bad angle injury it would affect what moves we could do. Our development of our psyche is the same and affects how we are in relationships, as facilitators and practitioners. Inner work aims to work on these issues and help us move with fluidity and openness.

The environment we find ourselves is also extremely important. Unsafe environments that we are not prepared for can cause more harm than good, be it an organisational or workshop setting. However we also need spaces that provide the conditions for bravery to work with issues that are uncomfortable and hard to address as this is not an easy journey. For this we need facilitators.

If we see facilitators role as bringing awareness to the world, sensing and working with people and their interactions, relationships and other dimensions so as to bring forward what the world needs of us we may look at the practice of “sitting in the fire” to get used to this uncomfortableness.

As a facilitator these environments can be supported by showing both vulnerability, the openness you can display in your own learning to model opening up for others as well as knowing your boundaries and taking accountability for your actions.

Finally all power dynamics are fractals, that is to say that a pattern that is happening at a smaller level will be happening at a wider scale and vice versa. For example a dynamic that is happening between two people might also be seen within the team and then again within a wider network or society as a whole. Therefore if there is a pattern of power that has not been addressed by a facilitator team it will start to play out into the workshop and equally where an organisation is not addressing power issues themselves they are unlikely able to be addressing it in the wider systems they are trying to change.

What does this mean for the work that we do?

So if these dynamics and patterns are playing out at all scales what might some (not all) strategies for how we address the way that we might relate?

Minimise power-over

I am going to start with this framing as I feel it is the hardest one to deal with. Coming from a position of power and privilege it is critical that this does not get side-lined. Donella Meadows in her paper — Leverage points: places to intervene in a system describe how often address a dynamic by looking at solving the problem rather than looking at the dynamic that is perpetuating it. For example anti poverty programmes are weak negative feedback loops, trying to balance out the stronger positive feedback loop of a systems that brings more and more “success to the successful”. In terms of relational dynamics it is far more effective to weaken the positive loops — in this case minimising power-over relationships.

I will risk repeating myself and highlighting the two insights from above and how we must also look at them as strategies for change

- Position awareness — individually, organisationally and at any scale. Acknowledge the power and privileges we have, for example what knowledge we are privileging. Be prepared to be open about it, find ways to talk about it, be humble with what you are doing — practice vulnerability.

- Understand and deal with our triggers and traumas — so that we start the learning journey of not creating harm (again at all levels). Become really comfortable with uncertainty, being uncomfortable so you can turn towards and be centred in challenging situations.

- Be open to having difficult conversations

- Practice letting go — what would it mean for the organisation to not exist, to write its own exit strategy? What if you personally were to live on a lower income, with less consumption? This also means getting out of the way of others.

- Transition power and resources — This means working with those in power and hold decisions over the resources to use their power to shift where and how decisions get made. For example funders hold a lot of power in change systems or policy makers across society.

- It sometimes takes a generation to shift a system as mind-sets and power shift. Consider what the trajectory is for people giving up or more shifting their (supposed) power, support shifts in identity, their sense of who they are in the world. Help them become enablers, elders and play a role with those who have more power then them as part of the transitional process. What are the rituals and ways we might celebrate, acknowledge the journey.

- Change the narrative that helps build this perspective shift, whilst also recognising that language is a form of knowledge and power. This might require doing discourse analysis to support reframing.

- People cannot be coerced, invite people in to develop the collective mandate — start using participatory methods to do this (see next section). I am not however saying that there is not a role for calling out or campaigning where harmful practices are pointed out however we do need to understand them in an ecosystem of changing relationships.

Set the conditions and enable power-with

- If you are facilitating these processes really model behaviour of being open to what might emerge and the way forward. Like above — be acutely aware of your power as holding a space, ensure that you do your inner work.

- Use the power that you do have to demonstrate and use participatory methods for decision making, working together and building coalitions. This means setting the container for working and relating, through being clear about mandates, roles and responsibilities and not assuming everyone knows how to work from the get go. Ensure there is participation in the production of knowledge and learning.

- Creating safe or brave spaces for people to work together. This might be preparing people to be able to be in the room together, investing time so that new ways of relating can be found. Change can only happen at the speed of trust.

- Transparency is critical for this, allowing the process to be seen and be open to be called to account and criticism — actively inviting in alternative views, seeking wisdom in the minority to improve the decisions and processes.

- Create liberating structures, new ways of organising, regenerative cultures and rules that enable self-organisation — there are different examples and literature on these different methods — for example Re-inventing organisations.

Enable power from with-in

Much of this is also a repetition of what has been said above — supporting inner work, addressing trauma and triggers and ensuring resources are put into this work.

- Place high value on lived experience as supposed to learnt experience — which usually manifests in approaches to learning and capacity building that are transactional, delivered to people not with. Value the learning process over the knowledge accumulation.

- Follow the principle with not on. An example of this might be not creating personas of different views and perspectives but actively bringing real people into design and futures processes.

- Work is needed in the liminal spaces, find the people who can be the bridges and give them resources both time, money and safe spaces to support the transition.

- Create transitional decision making forms — for example a shadow board, to build agency to transition power

- Devolve decision making — through the above strategies ensure that the decision happens closest to the impact

- Really understand the process of personal change and what that means societally– and recognise that everyone has their own stretch and time requirements

This list of actions are by no means exhaustive, they also do not address some of the actions needed for addressing some of the specific issues such as racism, but its aim is to start to think about relational strategies that might be beneficial to all these issues. Please do also share with us others you might have and what is missing..

So where does this leave me?

I am still struggling with the process of shifting the dynamics of power on a daily basis, from every interaction I have as a leader, teacher, facilitator, director, white UK woman, parent even, trying to bring awareness to what I am doing. How I have to both step up, use my power, stand up for what I believe in and set the conditions for others and in the same breath step back and get the hell out of the way and just shut up!

How I still feel rage or anger for people not doing enough and how it bubbles over and out as I don’t know where to always put those feeling and yet trying to heed my own insights that its a journey and you cannot undo centuries if not millennia of harm and oppression that has existed in the one moment you have in front of you. And yet you try and do something and then you know every action is just not quite enough or good enough and again you find yourself fumbling around in the dark.

How I also know there is still so much that I do not see, so much of our unconscious so much of that we are all still playing the game of the current system and thinking that we can somehow change it, that its forces and dynamics are still as yet unknown. How we are complicit every day in its powers.

And so one promise I will try and commit to myself is that I will not keep ignoring the calling of this question both in my own learning and in my practice and that of those I work with. That all I do know is that I need to keep coming back to it as in itself it also has an illusive enticing power of intrigue to the flow of life itself and how it has both caused great harm and yet if relationships are also what gives us great joy and a sense of flourishing it also has the potential to bring healing.

Many of the ideas in this article have been influenced by my reading and training in Processwork — including the work of Sitting in the Fire by Mindell. I am also grateful for those those I have been co-inquiring with over the years my colleagues, co-inquirers and funders, at Forum for the Future, School of System Change, Living Change, Boundless Roots and Lankelly Chase Foundation and New Girls Network.

Originally published at School of System Change

Director School of System Change, Forum for the Future

@annasquestions

Anna is passionate about designing and facilitating systems change programmes that support people, communities and organisations to transform their practice.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Organizing models for social change: Networks as an inclusive category

Creating social change of any sort requires organizing the people who have an interest in the issue or problem at hand. The global social impact space has a wide range of terms — networks, movements, alliances, consortiums, coalitions, communities, partnerships, forums, initiatives, campaigns, and more — for how people and groups are organized across geographies and topics to affect change. While the titles represent some variations in approach, orientation, and composition, these types of organizing models share a lot in common.

What should we understand about organizing models?

A quick search of definitions highlights the important differences and nuances of various types of organizing models. [1]

- Coalition — a temporary alliance of distinct parties for joint action.

- Consortium — a group formed to undertake an enterprise beyond the resources of any one member.

- Alliance — a formal agreement or association to further the common interests of members by merging efforts.

- Partnership — a formal relationship involving close cooperation between parties with specified and joint rights and responsibilities.

- Movement — a diffusely organized or heterogeneous group of people or organizations tending toward or favoring a generalized common goal.

What all of these models have in common is that they are about connecting and facilitating interactions between people or organizations to take action together. They convene groups around a shared purpose and merge efforts and resources towards collaborative action.

Organizing models also typically define who is involved, why, and how they plan to achieve their goals.

· Who — the people or organizations that have an interest in the issue or problem at hand and that are coming together.

· Why — the common interests amongst participants and the shared goals they seek to achieve together.

· How — the ways in which the participants are connecting, interacting, merging efforts, and undertaking collective action to achieve their shared goals.

Networks as an inclusive category of organizing models

At Collective Mind, we use the term “networks” to encompass this expansive range of organizing models and their common components.

Networks can come in all shapes and sizes. They can range from the informal — for example, a group of professionals with a shared interest in reducing inequality in their field who communicate via a Slack channel — to the highly formalized, such as a global network with organizational members in each country who formally apply for membership or an alliance of European NGOs formed on the basis of a legal arrangement for sharing funds and achieving shared goals. The category of network can include a pan-African movement organized through national associations and local community groups, all of whom participate in achieving a shared vision, as well as the hybrid setup of a US-based nonprofit that runs its own programs while also coordinating a network.

Whatever their labels, these networks seek to collectively and participatorily achieve goals that none of the participants can achieve by themselves. At their core, they integrate participants who have common interests and work together to achieve shared goals. That is where the power of networks lies.

[1] Definitions taken from Merriam-Webster, Cambridge Dictionary, and Dictionary.com

Originally Published at Collective Mind

Featured image by Kubko

Collective Mind seeks to build the efficiency, effectiveness, and impact of networks and the people who work for and with them. We believe that the way to solve the world’s most complex problems is through collective action – and that networks, in the ways that they organize people and organizations around a shared purpose, are the fit-for-purpose organizational model to harness resources, views, strengths, and assets to achieve that shared purpose.

Systems Practice, Abridged

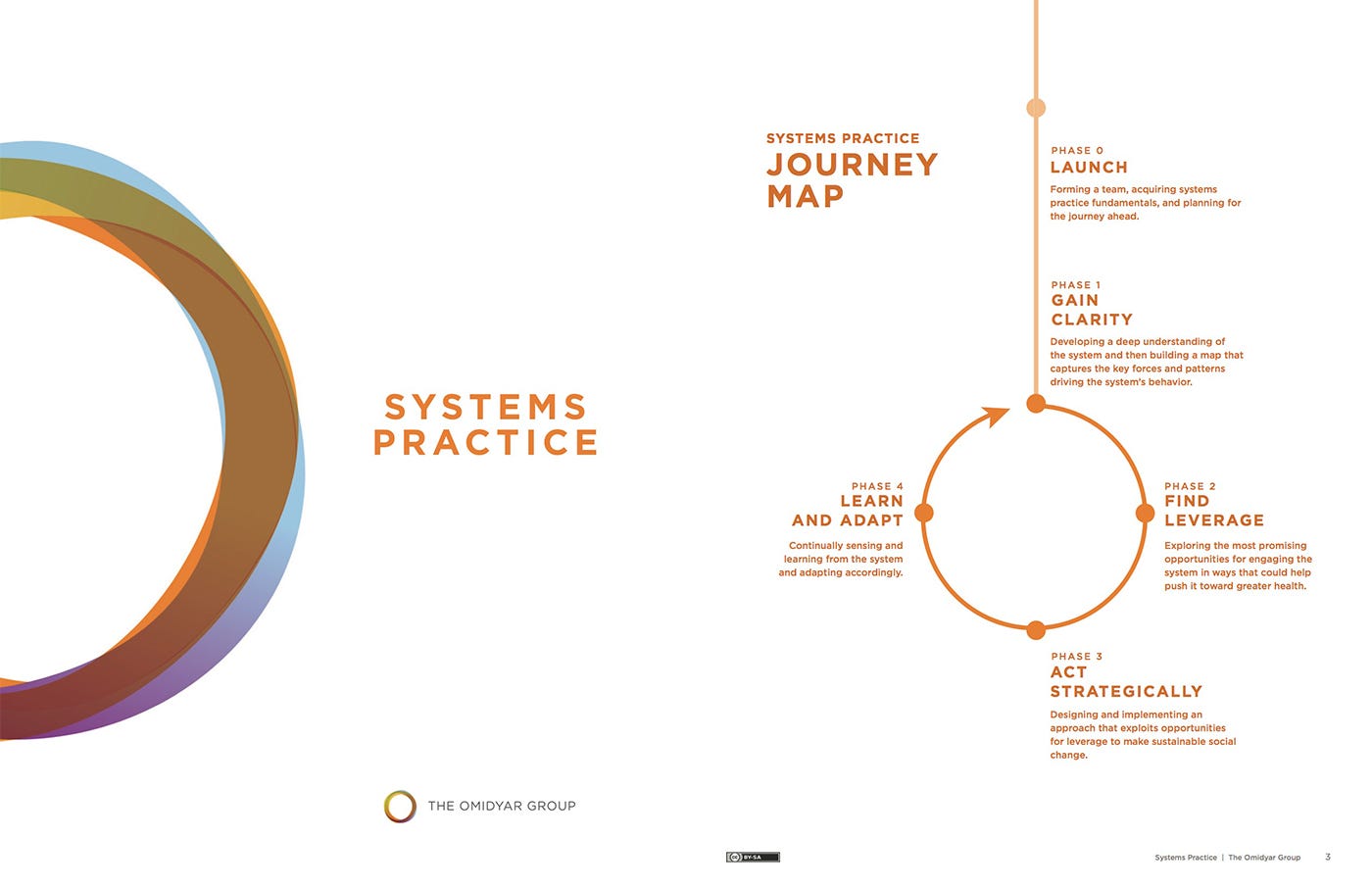

When you’re making a system map in Kumu, it’s important to have skill and familiarity with the tool itself, but it’s equally important to have an understanding of the concepts of systems thinking.

You can learn these concepts and learn Kumu at the same time if you follow the Systems Practice methodology developed by The Omidyar Group. When we’re mapping systems ourselves, teaching systems skills, or simply brushing up on our own skills, this methodology is one of our all-time favorites.

Notably, though, the Systems Practice methodology is time-consuming. The workbook itself is nearly 100 pages long, and it mandates weeks, if not months, of study and stakeholder engagement.

For serious system mapping work, spending this much time studying, thinking about, and mapping your system helps ensure you are addressing root causes rather than instituting quick fixes. In the long term, the time and resources you invest in Systems Practice will pay dividends.

But what if you’re not quite sold on the Systems Practice methodology yet? What if you haven’t encountered systems thinking before and just want to dip your toes in? Or what if you’re an expert or an educator with only a few hours to introduce Systems Practice to a fresh new group of systems thinkers?

At Kumu, we face this problem all the time! Whether we’re doing a product demo, giving one-on-one support to Kumu users, or leading day-long trainings, we rarely have more than a few hours to introduce Systems Practice, introduce Kumu itself, and get as close as possible to the first draft of a system map.

Give those constraints, and after plenty of trial and error, I’ve settled on an abridged version of Systems Practice that fits comfortably into a 2–4 hour session. In this article, I’ll share the main concepts and activities that comprise “Systems Practice, Abridged,” organized into the following sections:

- What is a Systems Practice? [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- The power of mapping with Kumu [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Applying systems thinking [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Incorporating others’ perspectives [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Leverage and learning

What is a Systems Practice? (15–30 mins)

Under time pressure, I gravitate toward a short and snappy definition of Systems Practice:

Systems Practice is a methodology for solving complex problems.

This definition is such a barebones collection of words that, at first glance, it hardly seems to do justice to the power and promise of Systems Practice. But, digging deeper, I think it unpacks nicely:

Systems Practice is a methodology…

Systems practice is decidedly not a simple tactic; it’s not something you can accomplish in a day; it’s not a band-aid or a quick fix. It’s a methodology composed from a full suite of techniques for studying and describing complex systems, then identifying appropriate actions to take to ensure that certain system dynamics persist and others fade away.

…for solving…

Systems Practice has a clearly defined outcome: solutions to your problem. Gaining knowledge and insight is a beautiful thing. I have a huge soft spot for research, data collection, experimentation, and analysis, but even I know that knowledge without practical action won’t help us address the major challenges of this century and beyond.

…complex problems.

Systems practice isn’t appropriate for all problems! It’s appropriate for complex problems, which you can identify by looking for the following characteristics:

- Understanding of the problem is low. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Consensus about what to do in response to the problem is low. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- The problem is not self-contained. It’s intimately connected to a dynamic and changing environment that is outside of your control. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Your intention is to make long term change rather than achieve short term goals.

The power of mapping with Kumu (30–60 mins)

A system map is one of the main deliverables that Systems Practice produces, and its purpose is not only to help you understand the context and identify potential solutions, but also to document your thoughts and decisions along they way.

Kumu is a tool for creating digital system maps that not only show the intricate structure of systems, but also allow you to create profiles, rich with metadata, for each of the factors, connections, and loops in the system. This approach encourages you to draw conclusions from the overall structure of the system, but still provides a great home for more precise information gathered from people with real-world experience in specific areas of the system.

As you implement a long-term solution, you’ll continually be able to return to the map to remember why a certain process or program was put in place, how small actions relate to the bigger picture, and what assumptions did or did not factor into the original decision-making process. Very important stuff!

That said, you don’t have to be a Kumu expert before you start working through the Systems Practice methodology. If you’ve never used Kumu before, there are only a few basic concepts you need to know that will help you dive in — I like to call this collection of concepts “Kumu 101”:

How do I get started with my first Kumu project?

I recommend working through our First Steps guide, which goes through everything you need to know to hit the ground running.

The First Steps guide will teach you how to pick a template, how to start building your system inside the map, how to design and customize the map, and how to invite other people to help you out.

Where can I go to learn more about Kumu?

To help you learn more about Kumu, we put together some great resources. First and foremost is our documentation website, where you can find guides on everything there is to know about Kumu.

You can also subscribe to this blog, check out the In Too Deep podcast, and follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Linkedin!

If I get stuck, where can I go for help?

If you get stuck and need advice, feel free to email us at support@kumu.io, or post in our public Slack workspace at chat.kumu.io. And if you have awesome work to share, we’d love to see it in either of those channels!

For more info and inspiration on what I like to cover when introducing Kumu and system mapping, check out our blog post on Kumu 101.

Applying systems thinking (30–45 mins)

If system mapping is the science of Systems Practice, systems thinking is definitely the art. Identifying a system’s factors, relationships, and feedback loops, with all of their categories, subcategories, archetypes, and metadata, is a complex process and will be a unique experience for each individual system you study.

Even so, there are a few tactics you can use to apply systems thinking and extract factors, relationships, and loops more quickly:

Define a guiding star and a near star

Your guiding star (you’ll likely have one) is the answer to the question, “What healthy, future system is your team passionate about working toward?” and your near stars (you’ll likely have more than one) are the answers to these questions:

- What have you learned about how to be effective in your sector? For example, what have you learned about how to counter human trafficking/ slavery? [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What outcomes are most important to your organization? For example, do you have organizational beliefs or values that cause you to prioritize specific populations or parts of the world or communities? [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What sub-sectors or outcomes play to your team and organization’s strengths (e.g., capacities, knowledge, networks)? [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What trends, research/new findings, or bright spots have you seen that point to promising approaches?

Another helpful framing idea: your guiding star is a broad, ambitious goal that will take 7–10 years to achieve, and near start are impactful but narrower goals that take 3–5 years to achieve.

Your guiding star and near star will often become the first factors that you add to your map.

Start with abstract categories, then get more specific

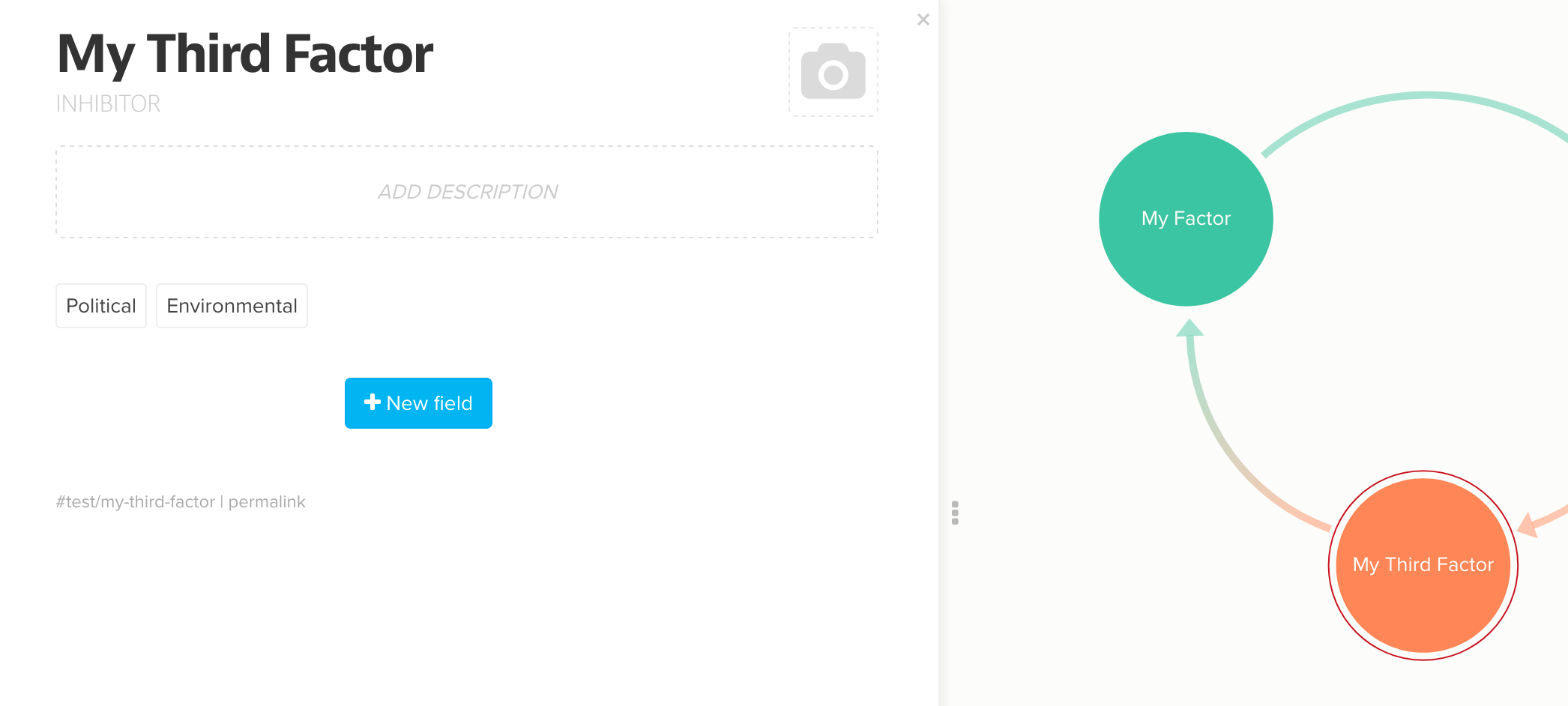

In the System Practice workbook, there’s a great activity that involves identifying “enablers” and “inhibitors” in your system. The workbook gives excellent definitions for these terms, so I’ll quote directly:

An enabler is a significant force in the environment that supports, encourages or increases the health and effectiveness of the system as defined in your guiding star.

An inhibitor is significant force in the environment that undermines or prevents the health and effectiveness of the system as defined in your guiding star.

In my experience, the “enablers vs. inhibitors” categories are superbly useful, but not necessarily because those categories exist in every system. Rather, the simple act of defining any abstract category of factors makes it easier to fill up the map with concrete examples.

Use the enablers/inhibitors dichotomy, or come up with your own categories (e.g. political, economic, social, environmental, and technological), then let those categories guide you toward specific factors that actually exist in your system.

Pro tip: If you’re adding factors to your Kumu map while you brainstorm, take a second or two to open the profile of each factor after you create it and add its category to the “Type” field (just underneath the label). Or, if your factor can fall into more than one category, add all of its categories as Tags:

Write a few paragraphs describing the essential narrative(s) of your system

Tell a few stories about your system, describe both the challenges you perceive and their potential solutions. If you’ve already added some factors to the map, incorporate those factors into your paragraphs.

Once you’ve written your paragraphs, the real work begins: translating your words into cause and effect relationships. There’s a trick to doing this well: the relationships will be hidden in the the verbs you used to describe your system.

Some relationships will be easy to find:

- Factor A increases the likelihood of Factor B

Given that sentence, you can confidently draw a connection from Factor A to Factor B on your map. But in real prose, causal relationships will usually be a little more difficult to find — they’ll be spread across multiple paragraphs, hidden by fancy sentence structures, or split up by interjections and asides. They’re also likely to use more creative words than “increase”, for example, “A is key to B,” or “In order to have Y, we need to have X first.”

If you get stuck on a factor that doesn’t seem to have any connections, just ask yourself:

- What increases/strengthens/leads to/creates this factor?

- What decreases/weakens/detracts from/destroys this factor?

Each new answer you find will be another connection for the map.

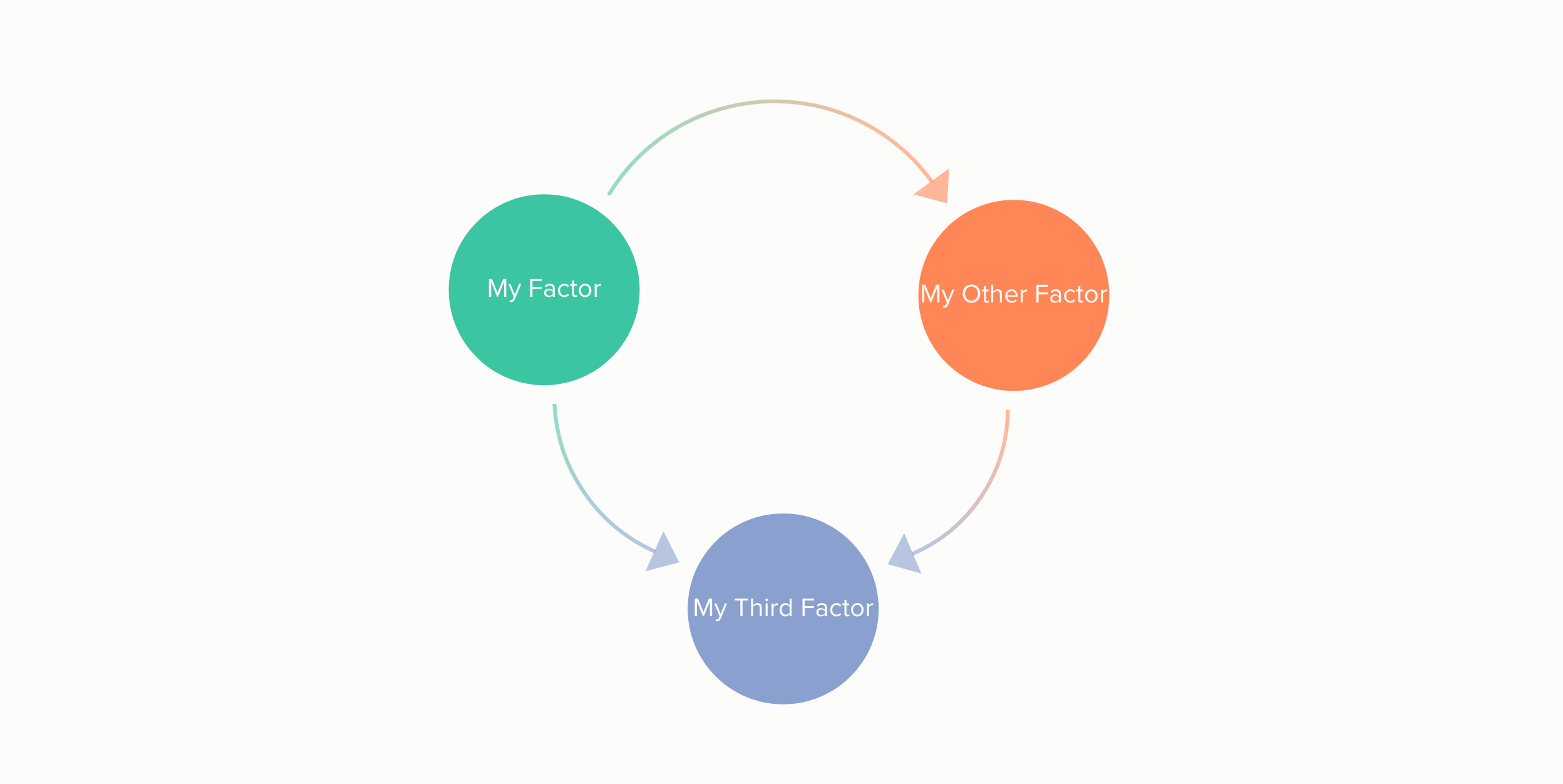

Look for loops

Colloquially, you can use the word “loop” to describe any kind of line that curves around in a circle or an oval. When you’re mapping systems in Kumu, you’ll find many groups of connections that meet that definition, but they aren’t necessarily the loops that a Systems Practitioner is looking for.

In a system map, my litmus test for discovering loops is to ask the question, “If I follow the arrows in this group of connections, can I get trapped?” If the answer is yes, I’ve found a loop, if not, the structure is not a loop, but might still be complex enough to deserve some further study.

Here’s an example of a structure that looks like a loop, but is not, because no matter which arrow I follow, I always end up at the same factor, escaping the trap:

On the other hand, if I reverse just one of the arrows in the structure, I inevitably get trapped going around and around in a circle:

This is the kind of loop we’re looking for in Systems Practice. It’s rarely so simple — in many cases, your loops will contain more than three connections, and they likely won’t be laid out in such a nice, circular shape.

But, after you’ve gotten a few practice rounds under your belt, I’m confident that you’ll have no trouble picking out groups of connections that cycle you through the same factors, over and over again, repeating the same dynamics, cycling through the same factors, over and over again, repeating the same…ahem. Moving on!

Incorporating others’ perspectives (45–90 mins)

If you’re going solo on your system map, hats off to you! It takes guts to try and understand a complex system all on your own. We invite you to return to this article anytime you need some extra guidance, or, if you need help, reach out to us in our public Slack workspace at chat.kumu.io.

If you’re working with a team, you can incorporate their perspectives into your Systems Practice with a simple team activity:

- Designate someone to be your Kumu mapmaker. This person should have a solid grasp on the concepts covered in the Kumu 101 section of this article. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Everyone else can take turns identifying factors, connections, and loops in the map, using the tactics described in the Introduction to Systems Thinking section of this article, while the designated mapmaker adds them into the Kumu map.

I’ve found that it’s fun and helpful to set a limit on how much each person can contribute — for example, set a rule that each person can add 3 items (i.e. factors or connections) to the map, or they can take a stab at identifying and naming one loop. After someone hits their limit, move on to the next person and get a fresh perspective!

Leverage and learning (30–90 mins)

If you work through everything I’ve outlined in this article so far, you’ll have completed only two of the five total sections in the Systems Practice workbook. Clearly, there’s much more work to do!

The final three sections of the workbook teach you how to:

- Identify actions you can take to make change in your system [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Strategically take those actions [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Learn from the results of those actions [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Adapt for the future

This work is very complex and important, and it’s arguably irresponsible to undertake it after only a few hours of systems study. But, in your abridged Systems Practice session, I do think it’s possible to sketch out an action plan, if only to familiarize yourself with the remaining steps of the process.

With that in mind, here are a few practical things you can do with your remaining time:

Identify leverage opportunities

In the context of Systems Practice, a “leverage opportunity” is an action that strikes a balance between feasibility and long-term positive impact in your system.

Explore that thought for a moment: acknowledge that there are many possible action you could take that will affect your system. Some of those actions require very little investment of time, talent, money, technology, or any other resource you have access to, and some require much more than the resources that are available to you. Some of these actions will create huge positive impact, some will create small positive impact, and some may even create negative impact.

More often than not, the actions that create the largest and most positive impact are also the least feasible.

To identify leverage opportunities, start by brainstorming actions you could take, anywhere in the system. Once you have a robust list, evaluate each action, and make explicit predictions about what type, quality, and quantity of resources each action requires, as well as what size of impact each action will make, and what potential ripple effects it might cause.

Narrow your list of actions down to include only the ones that seem to strike a balance between feasibility and impact. Remember that this is a judgement call —your system map and your feasibility & impact predictions can guide you, but at the end of the day, only you can decide which actions are worth pursuing!

Make a measurement and learning plan

You now have some pretty detailed predictions about how your leverage opportunities will affect you and your system, but how will you know if they come true? By measuring the effects!

In any system, the first actions you take are almost always imperfect, and you’ll need to learn from those imperfections, then pivot and adapt. Before taking action, you’ll want to have tools and processes in place to measure the effects, so that the next iteration will be even more successful.

Remember, the basic metrics we’re interested in are:

- What type, quality, and quantity of resources each action requires [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What magnitude of impact (positive or negative) each action will have [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- What results will emerge from the ripple effects caused by your actions

You can definitely add to that list as you see fit; every system will have unique measurement needs.

Once you know what metrics you’re interested in, commit to measuring them regularly — keep a journal, make a spreadsheet, talk into a tape recorder, build a robot that follows you around and watches everything you do — whatever it is, just make sure you’re measuring!

Most importantly, make an effort not to take these measurements alone. They are often subjective and tricky to pin down, so be sure to work with a team, interview stakeholders, and in general, involve other people and their perspectives in the measurement process.

Get ready for round 2!

I mentioned that Systems Practice is a methodology for solving complex problems, but you should also know that it’s a cycle.

As you act upon your system, you’ll change it, and those changes can be drastic, extremely subtle, or anything in between. When you observe changes in your system, you should return to your system map and update it to reflect the new real-world dynamics. After you update your map, you’ll of course need to rework your leverage opportunity predictions, and you may need to update your measurement strategy, too.

In short, the Systems Practice methodology requires that you continually revisit its techniques and tactics in order to adapt to your changing world.

That’s the essense of Systems Practice, Abridged! The full Systems Practice workbook is extremely well designed and well written, so we recommend working through it when you have time, but we hope that Systems Practice, Abridged can serve as a comprehensive overview for you or for any soon-to-be systems thinkers you’re teaching.

If you’d like to dig deeper into Systems Practice we encourage you to enroll in the Systems Practice course on +Acumen!

Originally published at Kumu.io

Frontend Developer at Kumu

I'm passionate about software development, data visualization, and applying science and technology in the majority world

INTERSECTIONALITY IN NETWORKS AND ORGANIZATION: WIDENING THE SCOPE OF INCLUSION AND DIVERSITY

Growing up, I remember my mother rising daily before the sun to make her way to work. After preparing herself for the day, she’d make a tiring journey into work, consisting primarily of easing slowly along the highway behind other workers headed in to start the day. From a young age, my mother’s commitment to her work stuck out to me, largely in part because it took so much out of her and rarely poured anything into her. Although I loved spending time with my mother at her Corporate America “office jobs,” raiding cabinets for fun supplies and spinning in spinny chairs, I resolved from a very young age that I would never work in an office.

Of course, in my limited eight year old scope, I could attribute all of her stress to the notion that what she did wasn’t very fun. Though, as I enter the workplace now so many years later, I realize that my mother’s stress would soon become my own, and was a seemingly shared stress amongst other Black working women. It had little to do with the type of industry, reports found that the same stress existed across varying levels of position and authority. It was a stress rooted in one-sided dedication, commitment and care.

Black women are more frequently the single head of household than any other demographic. Our appearance and hygiene are more often policed in the workplace. We are more likely to face unfair expectations and are statistically labeled amongst the lowest of expected specialized skills. However, Black women have been committed to working, presenting the highest labor force participation of all women for years.

Despite attempts on all fronts to create better conditions for working Americans (increased benefits, wages, and efforts targeting diversity, inclusion and equity) a lack of understanding of intersectionality has prevented a shift in opportunity from being available.

As our networks and organizations tepidly progress towards diversity and inclusion, the scope of complexity in this particular issue continues to widen. It would seem so far that inclusivity, and our understanding of it, have only begun to puncture the long-standing conservative barriers in our organizational cultures. Only through exploring intersectionality, and understanding it in the context of a network’s specific constituents, will we begin to progress in a more functional and cohesive manner.

Observing the past 60 years of US legislation regarding inclusion in the workplace, one could surmise that we have arrived at a precipice of sorts.

Between 1963 and 1990, multiple pieces of legislation were passed to protect against discrimination in the workplace including The Equal Pay and American with Disabilities Act.

How well do these protections hold up against an ever more precise ability to self-identify along social, sexual, and racial spectrums. Though these protected classes may seem well defined, our research and data collection methods have already outpaced our legislation. Using Equal Pay as an example, we’ve seen wage gaps narrowing between men and women in the decades following 1963. While women have managed to reduce the pay gap between white men’s wages and their own, black women currently earn 21% less than their white counterparts. It would seem that our efforts to empower women weren’t as precisely calculated, or executed, as we assumed they would be. And what about a black transgender women in the workplace?

Organizations are continually overhauling their processes in an effort to keep up with the times, and attract the best talent. We’ve seen companies implement robust recruitment programs, training modules and communication channels that are designed to protect, and even empower, their minority constituents. Unfortunately, reaping the benefits of these processes requires more nuanced thinking about the role of intersectionality, as it relates to race, gender, sexuality, culture and even the mission of your own organization.

Consider weaving more intersectionality informed diversity approaches into your networks by:

- Taking a Look at the Data:

- Get to know your members. Understand the social structures within your network. Observe the smaller networks that develop within your network. Spot the outliers. Use data to better serve your members by knowing who they are, and how they participate.

- Don’t Streamline:

- Cater to Your Organization. Streamlining will make your network more homogenous, but only on the surface. If you have rules and policies, barriers to entry, or specific expectations for your members, always be willing to append them on a case by case basis

- Be Continually Open to Improving Diversity and Inclusion Policies

- Implement an ongoing program designed to empower minorities in your organization. This should be led by minorities, and not just the most privileged or liked minority in the network. Give them the political power in your organization to make substantial changes. Without any power, they will quickly become disinterested. Create safe spaces, and safe communication channels for both suggestions and critiques.

- Lead the Way – Don’t Wait for Legislation

- I’ve worked in several organizations that seemed to be either in steep decline or stagnant. To avoid unknowingly plunging your organization into devastation, learn a lesson from each voice present.

About the Author

Ammie Kae Brooks is a Clinical Therapist, Writer, and Social Impact Consultant in the Chicagoland area. She is passionate about ending gender based violence within communities by cultivating digital and physical healing spaces for Black women, girls and families.

featured image found HERE

A Loosely-woven Basket to Contain a Thought

In Whose Story Is This? (A Hero Is a Disaster, 2019), Rebecca Solnit reminds us of Ursula Le Guin’s proposal of “the bottle as hero.” By this Le Guin means that instead of the easily-accessible dramatic story of the male-brandishing-spear and hunt being “heroic,” she considers women’s work of gathering into a bottle or basket true heroism, and worthy drama. In the early years of our human history, slaying created status for men, while weaving provided status for women. Weaving baskets is about integration of grasses as elements that make a whole, and “it is a technology that creates containers and models complexity” (p. 148).

(Coiled basket made by people of the Akimel O'odham, Gila and Salt Rivers of Arizona)

This image of the network as a woven basket that is greater than the sum of the grasses that comprise it, is a powerful metaphor for me. What do the social networks of relationships that we weave hold? What do they make possible? The container may be envisioned by a few, but the container itself, the thing that holds the gathered, is woven by the weaver of the many.

So what is this weaving, this “technology that creates containers?” In Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall-Kimmerer (2013) sees the weaver as one who nurtures the growth of the sweetgrass, harvests not from the edges, not from the youngest or oldest, not from those seeding, and only a small portion of the stand. Each sprig of grass is gently separated from the others to be cured and eventually woven back together in the new design of the basket. All of this is done with a sense of reciprocity – taking with gratitude and giving back with humbleness and joy – a mutuality that goes beyond simple gratitude but is based on that gratitude. It strikes me that the network weaving we do in communities is something akin to this. We prioritize the relationships, close triangles to pull the weave tighter, and we assess the connections to see if the pattern we are creating will serve our collective design. Seeing the network as a whole is like watching the design of the basket emerge. And seeing the emerging design enables the co-creation of its evolving form.

Our relationships are largely invisible as a whole to the collective and the interactions or conversations that create them are often transient. Jane Dutton calls the interactions between us high-quality connections (HQCs) when they are energized, engender positive regard and mutuality, are resilient, have emotional carrying capacity, and are highly generative (Dutton and Heaphy, 2003). HQCs can extend over time or be transient but they create a residual impact that makes the relational soil fertile with future possibility.

A social system map is a concrete container that makes the invisible visible. It is a way to capture a trace of those HQCs and holds them after the fact in a persistent way, to be seen over time, by the participants when they have the time, energy, and focus to perceive the parts or the whole. It can provide feedback to the collective about relational quality and structure that contributes to its self-awareness. Snapshots in time can provide a view of a network’s evolution, whether it is a system shifting network, a learning ecosystem, a campaign, a community of interest, community of practice, or some other form with purpose.

Segue … An Opportunity!

A prototype social system map was created this year for the Network Weaving Facebook group by the MasterMappers, a small group of mappers learning from each other that use the sumApp (survey) and Kumu (map visualizer) tools. MasterMappers convened a few gatherings (65 participants) to come up with an initial design and have led the implementation. The idea was to learn by doing, provide value to the Network Weaving community, and to use it as a tool to support the practice of network weaving in the community.

There are now 104 people participating in the map. It is interactive and is dynamically updated if any participant changes their personal information or their relationship status. We’d like to grow this map to get a large enough base of active users that we can all draw lessons from the experiences of creating it and using it.

The map has filters to slice and dice by different criteria. Different views capture participant interests, indicate what skills they have to offer the community, or what skills they need. Relationship types are plotted. Comments about relationships between individuals can be captured. And all of this is changeable as we continue to discover together what we want to know about each other.

Another view provides geographical location.

- If you haven’t yet joined the map, you can do so quite easily by following this opt-in link. By opting-in you’ll get an email from the MasterMappers (me, best.jim@gmail.com) with your own unique sumApp survey link.

- The survey captures information about you and your relationships to others in this Facebook community. The map is by and for the members of the Network Weaving Facebook group so if you aren’t a member, please join first.

- Here is a work-in-progress playlist of videos that help orient you to the map and mapping.

- Click here if you want to join our mapping community of practice, attend a sumApp On-Ramp (learn from other people’s maps), and/or get access to a wealth of information about Social System Mapping.

- If you want a rich description of social system mapping, see Christine Capra’s video. She and her husband Tim Hanson are the creators of sumApp, the survey tool. (Yay!)

See you on the map!

(Jim Best, best.jim@gmail.com)

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Dutton, J. E., & Heaphy, E. D. (2003). The power of high-quality connections. Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline, 3, 263-278.

Kimmerer, R. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

Solnit, R. (2019). Whose story is this? Old conflicts, new chapters.

Photo by Carrie Beth Williams on Unsplash

Appreciating the Complexity of Human Ecosystems

Networks are made of individuals. Each person is a complex system where we can’t control nor truly predict their behavior, so combining them to form a network can make things even messier! As a practitioner it’s my job to pay attention and support healthy, productive patterns that emerge from the network’s ecosystem. I was first introduced to the Human Systems Dynamics Institute (HSD) when we hired Glenda Eoyang to help facilitate a difficult transition we were facing in the Network. I was so impressed by how she was able to tap into the tension that existed and turn into something innovative that I later became an Associate of the Institute. The foundations of HSD supplemented my existing systems thinking practice allowing me to better see into the system of forces in the network and to be able to make sense of them so that I could be empowered to begin making a difference.

Sarah: How do the foundations of HSD help us appreciate the complexity of human ecosystems?

Royce: Through HSD, we learn that the complexity of human ecosystems emerges as we live, play, and work together. Over time, we generate system-wide patterns. Those patterns, then, influence the whole of the system. They also represent the system. For instance, in a community we honor long-held traditions as the patterns of our lives. In some organizations, we pride ourselves on patterns of safety or service.

HSD helps us see into those patterns. We understand how our interactions shape the patterns of our lives. We begin to see that the problems we face in today’s world are really patterns that have emerged over time. These may be patterns of bias or inclusion, peace or war, or conservation or waste. On a large scale, these may not be “solvable” patterns. Each individual, using HSD, can take small actions that can change the larger patterns over time.

That’s how HSD has helped me “appreciate” the complexity of human ecosystems. I can see that complexity. I don’t have to be baffled by events and issues that seem beyond my reach. I know that, even if I can’t change the world, I can change my little corner of it. When enough people network together in this human ecosystem, they can change it in even more powerful and far-reaching ways than I can alone.

Sarah: As networks become more diverse and introduce more difference into their systems, how do we leverage the powerful differences we bring to the table?

Royce: In HSD we focus on differences that make a real difference in the overall functions in our worlds. We may be of different genders, beliefs, backgrounds, races, or ethnic groups. And those differences sometimes do bring tension. On the other hand, we can look beyond our more immediate differences. We can come together to consider larger issues. These are the huge differences that matter for our future and for our planet. We can put the tensions of difference to better use.

Consider the work of the RE-AMP Network. Imagine what’s possible when people look beyond local differences to focus on the future of climate and energy use across the planet. The differences that matter can be the differences that help us accomplish a shared task. They can help us avert a shared disaster. We can move beyond the tensions that might have stopped us altogether.

The most productive work in a diverse network shifts focus from standing “nose-to-nose” about our differences. When we stand against others over differences that are less critical, each of us is weaker. If we stand “shoulder-to-shoulder” to take on a shared challenge, we each become stronger.

I know it’s not easy. Given challenges we face around the globe, I don’t know what other options there are. The real power in this approach emerges when it happens in small groups. Those small groups then, network with other small groups to increase the power as the network grows.

Sarah: How else can HSD methods and models help us care for our network’s ecosystems?

Royce: A number of HSD-based methods and models have a great deal to offer. The most basic, however, are probably the most useful and powerful.

Adaptive Action is a three-step, problem-solving method. It that helps you see, understand, and influence the patterns around you. It’s simple, but not easy. The model asks you three questions.

What? Begin by describing what you see and feel and hear. What are the facts? What are the aspirations? What data do you have? What are the patterns? You gather that all and ask the next question.

So What? You begin to explore the implications and meanings of information gathered in the “What?” stage. Most HSD-based models and methods help you make sense of those patterns. Whatever tools you use, this step helps you understand from multiple perspectives. You generate multiple options for action. You push beyond your usual boundaries. You go beyond what you generally can see on first glance. Then you move to the third question.

Now What? Which of the options makes the greatest sense? Which of the options is within reach for you? How will you implement that option? How will you know when it’s done? How will you know if it’s successful?

When you have finished those steps, you stop and go back to the first question to ask, “What?” again. Adaptive Action is an iterative process. You use what you learned in one round to inform your actions to complete the next.

A complex system is constantly changing and emergent. We have found Adaptive Action to be the only reliable way to move forward in such a system.

Inquiry is the other tool that is a foundation in the HSD world. We see inquiry as a way of living in the world. It allows us to stand inside our questions, rather than living out our assumptions. Glenda Eoyang, the founder of the field, talks about how answers have short shelf lives. In a complex world, answers never hold true for very long. What we prefer questions to gather the information that feeds our Adaptive Actions. HSD defines inquiry in a very specific way. We stand in inquiry when we:

We know that none of us will probably ever be able to be that open and comfortable in all situations. It’s a challenge to respond from that position every single time. It’s a stance we work on, and we help each other work on it throughout the network. Because if we don’t, there’s no way we can see and understand patterns locally or globally to build a better world. We will never be able to leverage our differences to address the issues that threaten us all. Finally, if we don’t stand in inquiry, we cannot engage productively in Adaptive Action.

For more information, visit our website at www.hsdinstitute.org or contact us at info@ hsdinstitute.org

Originally Posted by RE-AMP Network on September 23, 2019

Featured image found HERE

by Sarah Ann Shanahan, The RE-AMP Network and Royce Holladay, The Human Systems Dynamics Institute

Storytelling to Enable Systems Thinking

For a long time I developed models and inflicted them on other people. Fortunately, due to the interaction with others, it became apparent that it made more sense to become a storyteller of relationships and their implications.

This video offers thoughts on why it's not possible to sell systems thinking, or anything else to a person or an organization, and insights on how to offer the understanding of the benefits of shifting to systems thinking.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Scaffolding for System Shifting Networks

Networks come in all shapes and sizes. However, if you want to be a system shifting network you will need to put in place scaffolding so that transformation can emerge easily and quickly. In nature, billions of soil organisms and mycorrhizal fungal mats work together to form this type of scaffolding to distribute resources and support the growth of plants and trees as they create a forest.

There are 6 basic structures that work together to create an environment for rapid change. Some, such as innovation funds, have been prototyped by many different networks. Others, such as communications systems and governance systems, are still in their infancy. I encourage us to work together to experiment with these structures.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

1) A communications system that provides places, spaces, processes and protocols for individuals and projects in the network to communicate, interact, self-organize, learn and expand.

It includes a platform that has the capacity to provide for network-specific spaces, cross network spaces for networks to interact, and whole network of networks common spaces. Such a platform supports self-organizing: people with an interest to find each other, have discussions, move to action and be fully supported in that action, and then have easy pathways to share what is learned. This aspect of scaffolding is the least well-developed of all the elements and this lack is holding back the potential of networks to bring transformation of systems.

The next step is to develop a fully functioning platform. Four networks are planning to work collaboratively to develop such a platform. If your network is interested in joining a platform cooperative to work on this development, let us know.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

2) An innovation or activation fund that catalyzes and resources self-organizing, collaborative projects.

This aspect of network scaffolding is fairly well developed, with examples from the work of Leadership Learning Community (LLC), Go Philanthropy’s Networks in India, the Resonance Network and the WEB Network.

The idea is to jumpstart self-organizing and collaboration through small grants to collaborative projects. Only a few rounds of such funding are usually needed to tip the network into a self-organizing regime, where experimental, collaborative projects become the norm.

The next step in innovation funds is to have a second round of larger grants that grows out of what has been learned in the first round. In addition, more attention needs to be paid to harvesting learning from the set of projects funded.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

3) Communities of practice (CoPs) and learning popups where people, especially from Innovation Fund projects, can explore new topics, learn from each other, support each other with challenges, and share what they have learned with the larger network.

Communities of practice (CoPs) are also a fairly well-developed element. Most are monthly virtual sessions lasting 5-9 months with 25-75 participants. A typical session includes relationship building time often in breakout rooms, a short content/practice piece, a chance to practice a new process, with discussion on how to apply done in small group breakout sessions, commitments, peer assists for people with challenges, and sharing of what participants learned when they tried to apply a new process or technique.

Usually during a session new topics are identified and a learning pop-up (a one time session) is set up with a subset of the participants attending.

The next step is to more effectively capture the learning that emerges in these sessions and share it with the larger network and networks of networks.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

4) Catalysts: Catalysts help people in the network more quickly shift to network behaviors and processes (such as dismantling racism, self-organizing and learning). We have found that an investment in their training and making them easily accessible to projects and circles in the network can greatly amplify the speed of transformation. Both the Resonance Network and the WEB Network have facilitation pools that are working well.

A facilitation pool or network weaver pool is a group of already trained facilitators who learn how to become network facilitators, especially focusing on helping to facilitate and coordinate collaborative projects. However, they are acting as seeds of the new network culture, modeling behaviors, making sure that projects work on dismantling racism and hierarchy and showing participants new collaborative project skills and processes.

Learning weavers are people with writing, social media and graphics skills who capture stories and learnings and develop protocols for sharing learning. So far as I know, no networks have set up this role yet.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

5) A tracking and learning system for helping people change while also tracking transformative shifts and outcomes, along with a system for sharing learning within and across networks which can identify promising areas for spread and/or possible aggregated action with other networks. This area is just starting to be developed.

Some networks are using quick, web-based surveys (examples are those on network values, network leadership, collaborative skills, meeting assessment, and overall network assessment - most of these are in the resource section). These are reviewed immediately after taking and enable groups to identify strengths and challenge areas, then quickly design strategies to work on the challenge areas.

However, very few networks are consistently putting aside time for learning and/or sharing what they are learning in spite of the fact that without this element, networks are unlikely to be transformative. We need to make work in this area a much higher priority!

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

6) A governance system: protocols for co-design, advice and consent to support participative creation of the network and especially of the elements described above.

Scaffolding can be network-specific but we are working hard to design scaffolding where elements can also be deployed cross-network. We believe we can design scaffolding that has some “bounded” elements that preserve the sense of belongingness but other scaffolding that allows people to maximize their reach and influence and pool of potential partners for culture of health work.

If you have added any of these elements to your network, please let us know!

Start At Yes : building resilient networks

In working with communities to build resilient networks, I’ve noticed a pattern. Those who “start at yes” – listening for the possibilities, helping others make sense of their ideas, shining the light on contributors and the community as a whole – are vital to the health and hope of a network. As I encounter the “start at yes” people in my community work, I acknowledge to them the loveliness of their approach and ask how they acquired it. So far, only one said they didn’t know – they just assumed they were born with it.

Most of the people who start at yes say they had either a role model who emulated this attribute or someone who expected it of them – often, a parent or sometimes, a boss. Their self-awareness also interests me, because they realize they are making a choice about how they show up. If one person can do this, can a whole community? Can a community collectively change its mindset? Evidence suggests it is possible – but how to begin?

I began doodling a spiral list of phrases these “start at yes” folks use. The spiral looks like this:

At a community meeting one night, we started a conversation about mindset – and how people living there talked about their town. The pattern was one of discouraging phrases and fault-finding. While no one disagreed that a change was needed, there wasn’t a clear path to what would make it possible. We started thinking aloud about what we could do to experiment. This is when the fun began. Two people in the session were active in improvisational theater – improv. Why not try improv as an approach to a collective mindset shift? Doing what improv requires: Making a deliberate connection between the mindset of starting at yes – a willingness to go with it - and playing with possibilities.

The more we talked, the more we agreed that an injection of hope and making it second nature to incorporate others’ thinking into our choices and throwing the ball back to others and trusting them to act – could have a lasting effect. If nothing else, improv would allow community members to deepen connections, play together, better understand and temporarily inhabit a “we” mindset, and grow to trust their instincts. And if something falls flat, to pick themselves up and keep moving.

Improv relies on generosity – the success of one increases the possibilities of success of all, as is the case when building community. And improv is easy to get started – low cost, fun. If you’ve never done improv, I hope that you will be curious enough to explore it. One source that offers great information is http://www.improveveryday.com/resources. Somewhere in your network of connections or in your community, there are people well-acquainted enough with improv to help get things going.

One simple starting point is to take the phrases on the spiral, above, write one each on a sticky note. Introduce a story line – something a little far-fetched, like “I hear the train may start weekly runs to our town.” Then, have participants utilize the phrase on their sticky note to build on this story line. Begin by reading the story line aloud and choosing someone to go first, and let it go. Encourage people to play – be lighthearted and to let go of performance anxiety. The point is the interplay, not a perfect production.

Down the road, I will provide an update on any changes we see as a result of our improv collective leadership experiment. We realize that it will take early adopters, effort, repeated experimentation, and building new habits of mind to maximize the improv experience. We are building a pattern of play, learning, and un-learning. Stay tuned.

Please share your insights, experiences and questions in the comments section below.

MENDING THE COMMUNITY CUP

For years in conversations in organizations, within advocacy groups, and social change initiatives, I have heard variations of these themes:

- “We know we have to move beyond top-down approaches – how do we get more bottom up input and ideas?”

- “How do we get more diverse voices to the table? We need the input of the grassroots in the room.”

- “How do you engage the people on the ground with lived experience?”

Notice the images within these statements: they imply a vertical hierarchy where there is a top and bottom (e.g., grassroots, on the ground). Hierarchical thinking is so ingrained in our mindsets and how our organizations are set up that it can be hard to imagine another way. Yet, these vertical images are a conceptual overlay on reality. In Donella Meadows’ landmark article Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in System, she described 12 ways to intervene in a system, in increasing order of effectiveness, starting with #12 as the least. Near the top, #2 on her list is: The mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises. She writes: “The shared idea in the minds of society, the great big unstated assumptions—un-stated because unnecessary to state; everyone already knows them—constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works.” #1 is: The power to transcend paradigms.

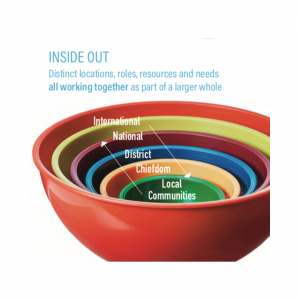

What happens when we choose different orienting metaphors? I recently had the opportunity to be part of a global learning gathering in Sierra Leone to see first hand a change initiative that intentionally uses specific metaphors and images to orient its work. Seeing these alternatives helped me discover what is possible when we create structures that arise and work from a different paradigm.

Sierra Leone is in West Africa, a country of six million people that endured a brutal civil war. John Caulker was a human rights advocate in Sierra Leone who was involved with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) after the war. In addition to the TRC, Sierra Leone had a Special Court, a hybrid national/international judicial process that indicted 13 people for war crimes. He saw a need for reconciliation work to mend the broken bonds of community – at the community level. John met Libby Hoffman, a US funder with Catalyst for Peace, who had a similar interest in supporting community-level healing and development in a systemic and sustained way. They created a partnership that has worked together for 12 years through a non-profit in Sierra Leone called Fambul Tok, which means ‘family talk.’