Thinking Like an Octopus (and With a Collaborative Heart): Evolving and Interlocking Networks

“You’ve got to keep asserting the complexity and the originality of life, and the multiplicity of it, and the facets of it.”

Toni Morrison

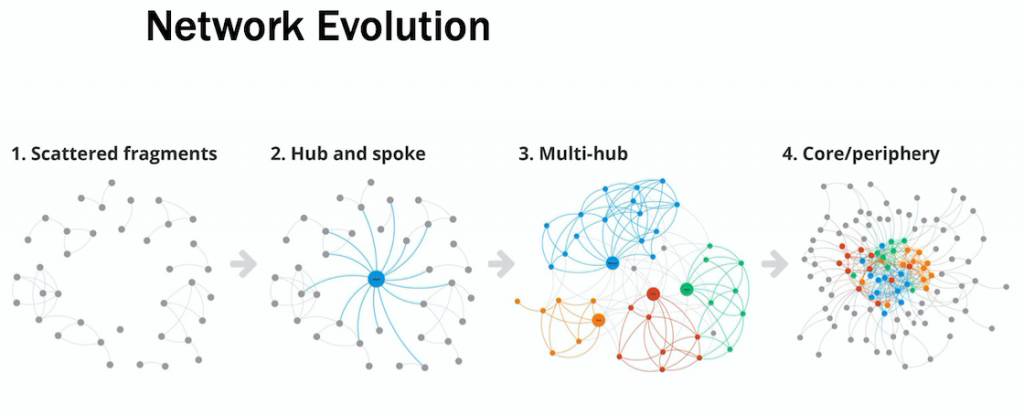

A network that I have been a part of for a number of years is seeing the emergent proliferation and strengthening of other related networks (some more adjacent than others) in its shared geographic and issue spaces. While this is welcomed overall, and sets up the potential for a more robust movement network and core-periphery structure (see image below), there are also some discussions within the network about how this proliferation constitutes an opportunity versus a looming threat or conflict.

There is plenty being written about the power of collaboration to solve complex problems and shift undesirable patterns, and one of the persistent barriers to collaboration is the default competitive and protective instinct found in individuals and groups. There are good and long-standing evolutionary reasons for “watching out for number one,” so this impulse can be fairly baked in. And there are also good reasons for understanding and leaning into “collaborative advantage” (see, for example, the work of evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson on multi-level selection).

“One step is to recognize that ‘ideologies extolling individualism, competition, untrammeled free markets, and conversely, disparaging cooperation and equality’ (as Turchin puts it) have no scientific justification. An unregulated organism is a dead organism, for the body politic no less than our own bodies.”

David Sloan Wilson

And of course, there are plenty of examples of “taking the high road” only to have someone else take advantage of this, which can leave us feeling like we are living in the prisoner’s dilemma. So what is a network to do? Well, if your values include collaboration and justice, then you do your best to lead by example. Which is where a recent network stewardship team conversation left us. And as often happens with this group, things continued to marinate and then one of our members sent the following beautiful email, reminding us of her experiences in a related network of networks.

“The dynamics we discussed reminded me a lot of what we have experienced at our organization since 2009, so if you’ll indulge me for a few minutes I’ll try to lay it out here. In late 2007, we piloted a new cooperative venture and launched the FL Collaborative in 2009. Our vision and aspirations were to bring a cross sector of people and organizations together to address the root causes of the problems facing our sector and relevant communities.

One of the first things the FL Collaborative really wanted to focus on was replicating the cooperative model, and our organization was tasked with doing that. And we did. Pretty soon it became clear that we couldn’t both do that and hold the bigger vision and aspirations. But to be honest, I didn’t want to admit that.

By 2011, the LC Network started to emerge from the FL Collaborative. My first reaction was that we have competition. But very soon it became clear that the LC Network was serving a role our staff and the FL Collaborative couldn’t serve. The LC Network was beginning to pull together elements of what it takes to shift the supply chain from one that is value-less to one that is value-full. The kind of technical support the sector and visionaries needed began to emerge through the LC Network.

By 2014, the SF Network (another network) began to percolate out of the FL Collaborative. And again I found myself triggered by the potential competition. What the SF Network was beginning to offer was the ‘social’ space. When our organization and the FL Collaborative were hosting a series of community gatherings and various social events that allowed us to have a public facing part, SF was emerging as being able to offer that. Another thing we could take off of our staff’s plate so we can focus on our bigger vision and aspirations.

The FL Collaborative, in the meanwhile, began to morph into the political and advocacy space. That’s where we think through policy shifts, organizing opportunities, connectivity, and alignment around the broader vision of what the future of the sector and larger system can look like and what it might take to get us there. Those who are engaged in each of these networks are doing things that they can easily wrap their heads around and inspires them most.

Today, I talk about these three networks as three tentacles of an octopus with our organization holding the space of the head of the octopus. Because our staff was not liberated to focus more fully on the shared values, bigger vision, the bigger story, connectivity, etc., all these three networks are interlocked by a shared set of values, a common vision, and organizing strategies.

Our staff are the ones who are asking the bigger questions of each of these networks when they seem to go off track. We are the ones who are finding the resources needed to get them to think about how racial equity is or isn’t showing up there (and we get most of that from [the network for which the readers of the email are the stewardship team]). So without sounding too egotistical, our staff is tasked with holding the moral center of all of this work whether it comes to the connections, strategies, resources, stories, organizing, etc. There is probably a better word than the moral center, but that’s the only thing that is coming to me right now.

More tentacles might emerge, and I hope they do as we identify gaps in this work. And I hope I can remain humble enough to not see them as competition but as a valuable addition to the family.“

It takes work, real intention and effort, to stay grounded and humble, to practice discernment and to keep perspective, to keep asserting the larger picture of complexity, to honor the need for deeper collaboration and more allies, to have faith in the possibilities that we cannot yet see through the growing entanglement of intersections. Even better when you can depend on others to help you out with this! With #gratitude to so many.

“Weave real connections, create real nodes, build real houses.

Live a life you can endure: Make love that is loving.

Keep tangling and interweaving and taking more in,

a thicket and bramble wilderness to the outside but to us

interconnected with rabbit runs and burrows and lairs.Live as if you liked yourself, and it may happen:

reach out, keep reaching out, keep bringing in.

This is how we are going to live for a long time: not always,

for every gardener knows that after the digging, after

the planting,

after the long season of tending and growth, the harvest comes.”

Marge Piercy, from her poem “Seven of Pentacles”

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Featured Image from Giulian Frisoni

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate at the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC). Much of his work entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food, education, public health, and economic systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Appreciating the Complexity of Human Ecosystems

Networks are made of individuals. Each person is a complex system where we can’t control nor truly predict their behavior, so combining them to form a network can make things even messier! As a practitioner it’s my job to pay attention and support healthy, productive patterns that emerge from the network’s ecosystem. I was first introduced to the Human Systems Dynamics Institute (HSD) when we hired Glenda Eoyang to help facilitate a difficult transition we were facing in the Network. I was so impressed by how she was able to tap into the tension that existed and turn into something innovative that I later became an Associate of the Institute. The foundations of HSD supplemented my existing systems thinking practice allowing me to better see into the system of forces in the network and to be able to make sense of them so that I could be empowered to begin making a difference.

Sarah: How do the foundations of HSD help us appreciate the complexity of human ecosystems?

Royce: Through HSD, we learn that the complexity of human ecosystems emerges as we live, play, and work together. Over time, we generate system-wide patterns. Those patterns, then, influence the whole of the system. They also represent the system. For instance, in a community we honor long-held traditions as the patterns of our lives. In some organizations, we pride ourselves on patterns of safety or service.

HSD helps us see into those patterns. We understand how our interactions shape the patterns of our lives. We begin to see that the problems we face in today’s world are really patterns that have emerged over time. These may be patterns of bias or inclusion, peace or war, or conservation or waste. On a large scale, these may not be “solvable” patterns. Each individual, using HSD, can take small actions that can change the larger patterns over time.

That’s how HSD has helped me “appreciate” the complexity of human ecosystems. I can see that complexity. I don’t have to be baffled by events and issues that seem beyond my reach. I know that, even if I can’t change the world, I can change my little corner of it. When enough people network together in this human ecosystem, they can change it in even more powerful and far-reaching ways than I can alone.

Sarah: As networks become more diverse and introduce more difference into their systems, how do we leverage the powerful differences we bring to the table?

Royce: In HSD we focus on differences that make a real difference in the overall functions in our worlds. We may be of different genders, beliefs, backgrounds, races, or ethnic groups. And those differences sometimes do bring tension. On the other hand, we can look beyond our more immediate differences. We can come together to consider larger issues. These are the huge differences that matter for our future and for our planet. We can put the tensions of difference to better use.

Consider the work of the RE-AMP Network. Imagine what’s possible when people look beyond local differences to focus on the future of climate and energy use across the planet. The differences that matter can be the differences that help us accomplish a shared task. They can help us avert a shared disaster. We can move beyond the tensions that might have stopped us altogether.

The most productive work in a diverse network shifts focus from standing “nose-to-nose” about our differences. When we stand against others over differences that are less critical, each of us is weaker. If we stand “shoulder-to-shoulder” to take on a shared challenge, we each become stronger.

I know it’s not easy. Given challenges we face around the globe, I don’t know what other options there are. The real power in this approach emerges when it happens in small groups. Those small groups then, network with other small groups to increase the power as the network grows.

Sarah: How else can HSD methods and models help us care for our network’s ecosystems?

Royce: A number of HSD-based methods and models have a great deal to offer. The most basic, however, are probably the most useful and powerful.

Adaptive Action is a three-step, problem-solving method. It that helps you see, understand, and influence the patterns around you. It’s simple, but not easy. The model asks you three questions.

What? Begin by describing what you see and feel and hear. What are the facts? What are the aspirations? What data do you have? What are the patterns? You gather that all and ask the next question.

So What? You begin to explore the implications and meanings of information gathered in the “What?” stage. Most HSD-based models and methods help you make sense of those patterns. Whatever tools you use, this step helps you understand from multiple perspectives. You generate multiple options for action. You push beyond your usual boundaries. You go beyond what you generally can see on first glance. Then you move to the third question.

Now What? Which of the options makes the greatest sense? Which of the options is within reach for you? How will you implement that option? How will you know when it’s done? How will you know if it’s successful?

When you have finished those steps, you stop and go back to the first question to ask, “What?” again. Adaptive Action is an iterative process. You use what you learned in one round to inform your actions to complete the next.

A complex system is constantly changing and emergent. We have found Adaptive Action to be the only reliable way to move forward in such a system.

Inquiry is the other tool that is a foundation in the HSD world. We see inquiry as a way of living in the world. It allows us to stand inside our questions, rather than living out our assumptions. Glenda Eoyang, the founder of the field, talks about how answers have short shelf lives. In a complex world, answers never hold true for very long. What we prefer questions to gather the information that feeds our Adaptive Actions. HSD defines inquiry in a very specific way. We stand in inquiry when we:

We know that none of us will probably ever be able to be that open and comfortable in all situations. It’s a challenge to respond from that position every single time. It’s a stance we work on, and we help each other work on it throughout the network. Because if we don’t, there’s no way we can see and understand patterns locally or globally to build a better world. We will never be able to leverage our differences to address the issues that threaten us all. Finally, if we don’t stand in inquiry, we cannot engage productively in Adaptive Action.

For more information, visit our website at www.hsdinstitute.org or contact us at info@ hsdinstitute.org

Originally Posted by RE-AMP Network on September 23, 2019

Featured image found HERE

by Sarah Ann Shanahan, The RE-AMP Network and Royce Holladay, The Human Systems Dynamics Institute

Liberating Structures in Network Development

When working in a network comprised of technical folks, it is easy stay in the familiar territory of presenting knowledge when the network gathers. Sometimes assumptions are made about scientists, policy makers, or engineers and how they prefer to interact at a face to face meeting. "Watch that “fluffy” stuff!"

My sense is a lot of this push-back originates in bad experiences where “interactive methods” were used for interactivity and perhaps less focused on the purpose at hand. With this in mind, I had a blast developing an agenda and coaching the facilitators for the Floodplains by Design Network gathering. I wanted to reflect and pull out some of the highlights of the process, both to acknowledge the fabulous team and the network participants, and to give some clarity on designing for networks, especially technically oriented networks.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Ditch the tables: People walked into the room to find a chair set of concentric circles – and were surprised. Coached to put their coats and backpacks to the side, there was a sense of “what is happening?” The folks kicking off the meeting had to adopt a new position to speak to and within a circle, but they quickly got the beat. Without tables, it was as simple as turning to someone to engage in conversation, look across the room to notice faces. The conversational sound level never wavered! [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Nurture network relationships: Networks balance on the three legs we often use to define communities of practice: community (relationship), domain (what we care about – in this case integrated floodplain design), and practice (what we actually DO!) It is easy in a technical field to skip the community element so we started the day with a round of Impromptu Networking facilitating three rounds of short conversations about what we are grateful for in this work. Three new or deepened relationships along with domain knowledge! No fluffy “icebreaker.” The team crafted the invitation so it would resonate with the people in the room – something, by the way, I would have gotten wrong had I designed by myself. TEAMS, people, TEAMS! [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The knowledge is in the room: use it! We used a modified version of Shift and Share to highlight as many stories of integrated floodplain work as we could to spotlight both the small and big steps being taken, and surfacing useful lessons for spreading. Along the way, people connect and relationships are nurtured in these rotating, purposeful conversations. We divided the short 5 minute talks, each followed by 10 minutes of conversational Q&A into five thematic “pods,” each with a “poderator” to help track time and capture highlights. We fully encouraged everyone to vote with their feet and move between talks, stay in a pod, visit all the pods, or just hover and bumblebee around. I was surprised that quite a few people stuck to a single pod and suspect there was growing identification and affinity around the pod topics. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Networks that rely primarily on voluntary participation need to focus on what matters, not on EVERYTHING. To help identify what to STOP doing, we did TRIZ, a reverse engineering process to identify the stuff we are doing that is not adding value. This one baffled some people in the room, leading us to consider how we might deepen the structure if we had a “do-over.” But we discovered later in debriefings that some people really got it and came to some tough conclusions about how the work might need to shift. So it may have also been a little bit of “elephant in the room” going on. I found it fascinating to watch the dynamics of acknowledging that sometimes the stuff we are doing doesn’t matter. A tough one. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Always find the next step. From the TRIZ we invited people to think about their 15% solution of what they could stop doing, and recommendations to the wider network of the more gnarly things that require a bigger lift to stop at a larger level. There were a few very concrete network recommendations, and some people began to crack open that they DID have some agency to stop things — or start them. That is always the temptation, to add before we clear the decks a bit. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Use the knowledge in the room. As we started the day by noticing the knowledge in each other, so we wrapped things up with Troika Consulting to get specific feedback on the 15% solutions. In knee-to-knee trios, people dug in to help each other. When we asked for a show of hands of who gained valuable “consulting” from their peers, almost every hand in the room went up. In after-event conversations people noted that this activity and the Shift and Share had high value for them. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Don’t forget the reflection with space for every voice. We finished in a circle, just like we started, with a “Just Three Words” debrief with everyone having a chance to say something or pass. Many of the words were captured on the right side of the visual above… you may notice a pattern. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

There were a lot of smiles at the end of the day. The facilitation team did a fabulous job – mama mia, were they talented. The feedback was both positive and criticisms were super constructive, instead of generally grumpy. There was, from where I observed, a tangible pulse of energy.

All kinds of people find value in engagement. Some need it a bit slower, some a bit faster, some need more space for reflection. But in a learning network, we need each other, so we need to design our meetings to truly BE with and ENGAGE with each other. Hats off to the Floodplains By Design team who had the courage to step outside of the “way things are done” and create that dynamic design. You KEEP GOING Heather, Carol, Courtney, Leah and all the shift and share speakers/poderators!

Read more…

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Originally published on 6.6.19 at Full Circle Associates.

Network Evaluation

In complex settings, causality is also complex. We cannot identify a single action that will produce the outcomes we want. We often have to experiment, trying out a number of actions or strategies and then notice what about those exploratory forays worked.

In the process of examining or reflecting on what we did, we often make breakthroughs in our thinking about the situation or problem and this helps us move to more effective actions.

For example, in combating infections in a hospital, we notice that when housekeeping staff work closely with – and are respected by – nursing staff and doctors, the resulting preventative actions are more innovative and effective. This insight leads us to become more inclusive in other aspects of our work, making sure that staff from many different roles work together on solutions. As a result, our hospital becomes a better place for both patients and staff. Complexity theorists use the term emergence to describe such new ways of operating that arise from this combination of self-organized experiments and reflection.

Of course, complex causality makes it difficult to determine whether a particular organization’s strategy is working or making a difference. And, in response to the complexity of problems, organizations in many communities have begun to work in networks so that they can utilize their differences to be more innovative and experimental and so they can access the power of scale, aggregation and diffusion.

A critical question then becomes: How do we determine the value of these networks? How are they contributing (or not) to the solution of problems? How can we tell if these networks are worth our investme nt?

We are just beginning to explore this terrain, but already we have developed a 3 faceted evaluative process that can be engaged in collaboratively by foundations, organizations and the individuals they are hoping to assist in some way. This evaluative process is meant to be inclusive and engaging, as well as developmental. Participants gain new understandings as a result of this process, and often need to restructure activities and even outcomes as they proceed.

Click here to download Network Evaluation.

Microtrends To Amplify for Transformation

How does change happen? I saw a book in the airport about microtrends and how they give a glimpse of the possible future. Microtrends are new behaviors, actions or directions that are just starting to emerge but have the energy and excitement to expand into something significant.

I’ve long thought that dramatic and rapid change happens when we see the opportunities in new microtrends and work collaboratively to support and spread those new directions.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Some of the microtrends I see are:

- Antiracism work, dismantling white supremacy culture, understanding structural racism: dismantling Racism - Resource Generationhttps://resourcegeneration.org/wp-content/uploads/.../2016-dRworks-workbook.pdf We can’t collaborate effectively if we don’t know how to be peers.

- Youth leadership: https://climateemergencydeclaration.org/climate-emergency-declarations-cover-15-million-citizens “An estimated number of more than a million people in ca. 130 countries demonstrated at about 2200 events worldwide on March 24.[1][36] “

- New approaches to clothing: “no new clothes” pledges, upcycling clothing, groups making thousands of shopping bags from cloth scraps and used clothing https://boomerangbags.org; https://sew-seamless.com/the-pledge/

- Healing and arts driving change: Resonance Network is convening healers and artists to identify collaborations and ways to build community.

- Governance networks and participation: food policy councils writing policy for city sustainability plans.

- New community places and spaces: maker spaces, community and school gardens, co-working spaces, libraries adding functions like showers and PO Boxes for homeless people.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

What microtrends do you see? Let us know in the comments below.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="40px"]

How can we help these new directions go viral?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Communities of Practice

One of the most powerful ways to amplify an emerging trend is to virtually convene groups or networks around the country (or world) who are working in this area as a community of practice where they can share what they have been learning in their local project(s), get support for challenges and learn more about building expanding networks of networks. This information could then be distilled and shared broadly to other communities so that they can quickly implement and adapt the new strategies.

I feel that supporting these types of communities of practice is one of the most important ways foundations can increase their impact.

Another way to expand your approach is to find other communities who want to experiment and try out your strategy and then set up virtual sessions over a six month period where you can share what you have done. These sessions should also help people plan and strategize how they can adapt your ideas to their community. Having the sessions last over a six month period will give the communities time to try out specific steps, them come back to the group and talk about their successes and challenges. This is like the community of practice idea described above but with newbies. You can do this if you add $15-30,000 to grants you apply for to cover the staff time to facilitate these sessions and coach individual communities between sessions.

Another version of this is to turn what you have learned into products that you can share and/or sell to others. The Food Corridor did this when they developed a Shared Kitchen Management Tool.

Another final way to accelerate the expansion of emerging practices is to provide support for network support structures. In addition to resources for communities of practice, networks around emerging areas need to develop communications ecosystems for expansion. This is a huge gap in that platforms that fully support self-organizing and the sharing of curated information do not currently exist. But patching together the use of zoom, google docs, discussion groups such a Facebook groups or Buddypress, slack and email/enewsletters is a start. Another support that networks need for expansion is training/information in skills such as:

- using self-organizing strategies to expand your network [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Facilitating deep reflection so that your strategy is continually improving and making breakthroughs[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- developing information toolkits from your practice and experience so that others in other communities can adapt your strategy [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Identifying existing networks that may be interested in helping their projects or communities try out your strategies and having conversations with them.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

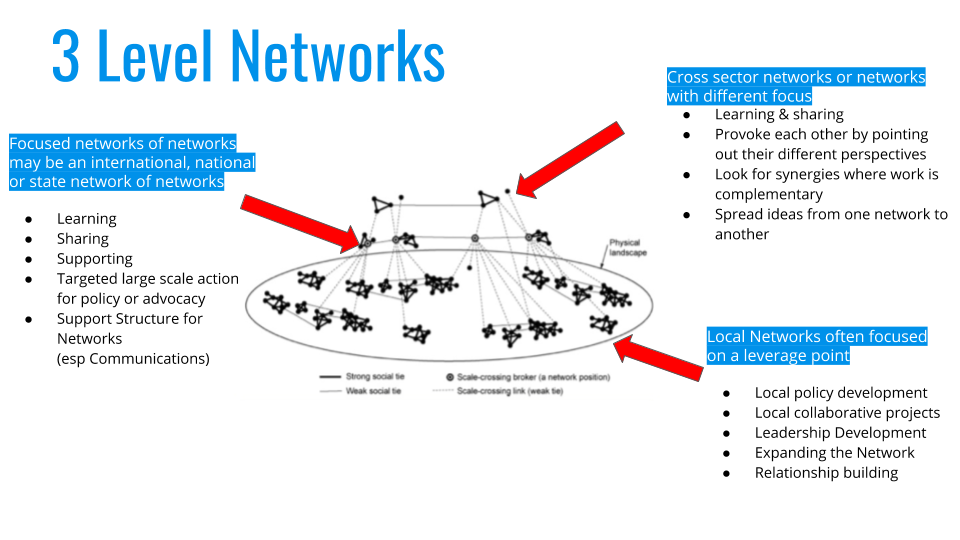

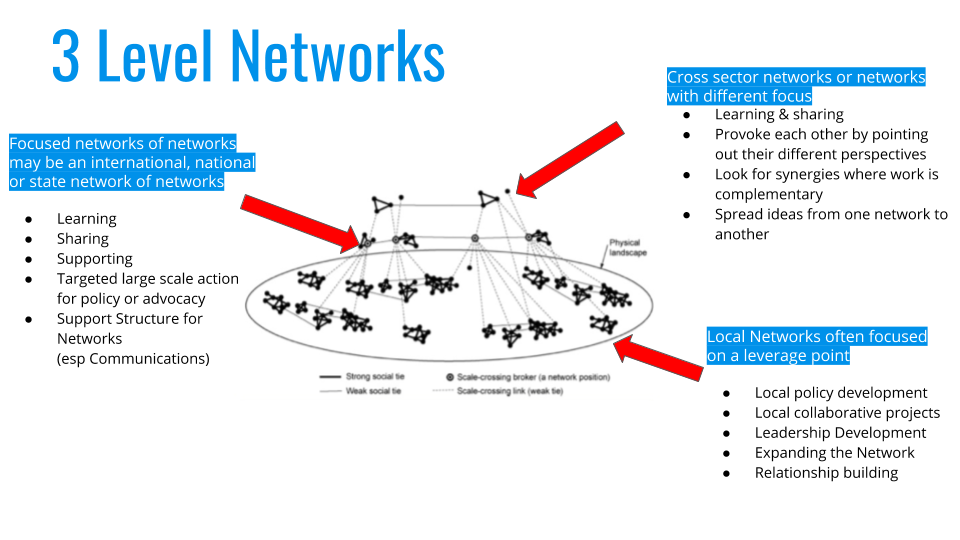

3 Level Networks

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Networks of networks have huge potential. They encourage the kinds of aggregation and numbers that can result in successful campaigns and policy initiatives.

They also can convene innovative projects from around the country (or world) to learn from each other, support each other and provoke each other to expand how they think about what they are working on.

Transformation or system shifting requires networks to be involved in networks of networks. This diagram and activity is designed to help networks develop networks of networks to maximize their impact.

CLICK HERE to access the 3 Level Networks download.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

The Transformative Power of Networks of Networks

Three Level Networks for Transformation

I’ve mentioned before that transformation or system shifting requires networks to be involved in networks of networks. This blog post will explain why every network needs to be part of and explicitly develop networks of networks to maximize their impact.

Networks need to be part of three types of networks, shown in the drawing below.

1. Local Networks

Local networks are networks formed in a particular locale, usually a city, town or in rural areas or a multi-county region.

Often local networks focus on a particular issue area, problem or alternative. Examples range from local food networks and local culture of health networks, to local climate change networks. Although a network may be catalyzed as part of a national effort (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s culture of health efforts, for example), it’s local roots in a set of specific local communities is critical for success.

Local networks are where small but concrete collaborative projects can be nurtured, and where residents can build new leadership skills as network weavers. Each local project is an opportunity to invite in new people and thus expand and diversify the network.

Local networks can also be very effective in advocacy and in policy work. For example, many local food policy councils are writing the food section of local sustainability plans (which city councils are approving with few or no changes).

Many local communities have informal networks, especially among nonprofits. Their staff probably know each other and may collaborate on the occasional project. But any community can become much more effective by making their local network more intentional.

This usually means:

- convening not only area nonprofits, but including government officials and agencies, businesses, and residents

- determining a purpose for the network which is essential to help focus collaborative efforts

- Identifying leverage points where change is more likely to occur

- forming work groups to collaborate around those leverage point

2. Focused Networks

Focused networks are networks, often national (though they may be state, multi-state or international), that focus on a particular issue, problem or alternative.

Often these are branded networks (have a specific name i.e. 350.org rather than environmental network) whose participants are individuals, organizations or local networks. So, for example, the Center for a Livable Future at Johns Hopkins has helped build a national network of local and state food policy councils. They have a lively listserv for sharing information and discussion, and frequent webinars and videoconferences.

Not all focused networks help foster local networks, but when they do, they gain access to lots of innovation and usually find that this strategy enables them to rapidly expand their national network. In addition, when national networks convene local networks, local networks can learn about the innovations happening in other communities and adapt those successes in their networks. So instead of simply focusing on individual local leaders, as many focused networks do, they could encourage and support the local leaders to form local networks. Center for a Livable Future did this by having a series of virtual sessions on how to create local food system networks.

Funders could amplify this catalytic and convening role for national networks by providing funds for Innovation Funds. Summer Matters, a network of summer programs for children, for example, set up an Innovation Fund to encourage their local members to form collaborative projects in their local community. When Innovation Fund projects are convened virtually, they can better capture breakouts and innovations to share with the larger network. In addition, the funded groups form a peer support network which generally last beyond the funded period.

I’d love to hear stories of focused networks that proactively helped local networks form...please share your experience in the comments below.

Focused networks are often able to mobilize large numbers of people and/or organizations to do advocacy or actions, or conduct policy initiatives. However, if they do these in a self-organizing fashion, i.e. encouraging people to work with others on posters for marches or for visits to legislators, and at the same time provide tools and encouragement to continue self-organizing when they return home, they can greatly increase their impact.

3. Networks With Other Networks

Networks can really benefit when they network with other networks. These types of networks help networks be transformative either through their differences or through their power of aggregation..

However, this type of network is most likely to be neglected. These networks can be one of three different kinds:

- networks of networks with a similar focus formed to create the numbers needed for effective large actions

- cross sector networks

- networks that are quite different in purpose but can be constructively provocative for each other and stretch everyone’s world views

Aggregated networks are composed of branded networks that are working on a similar focal area - for example environmental and climate change - who can work together, especially on large-scale actions and campaigns or on policy initiatives, to have much greater chance of serious impact than could result from a single network’s action.

Most of these networks are loosely linked to others like themselves but few have explicitly met to discuss ways they can share information or identify emergent opportunity areas where they might work together. Many aggregated networks are formed for marches, such as the 2014 climate change march in New York City. However, like this one which was orchestrated by a single organization (350.org), the network brought together by this march was short lived.

We strongly encourage national networks to begin reaching out to other related networks and meet as peers not just on joint marches and actions, but to understand the system they are trying to change, determine who is working on what, and figure out how they might have some protocols for sharing information and have convenings to share what each is learning.

This is something I’m particularly interested in working on, so if you are too, get in touch with me at juneholley at gmail.

Cross sector network of networks are when a network invites in or networks with entities or networks from different sectors. For example, a local food network might create a larger network that includes local policy council networks, local food businesses networks such as restaurant associations, farmers, and manufacturers, markets such as schools and hospitals, and government officials and agencies. Including participants from different sectors accelerates shifting of the food economy: the network can help markets and producers better connect, for example, to increase production of local food, or it can create food policy proposals that will be easily approved since a wide ranges of perspectives helped create them.

Another example of cross sector networks of networks are those that form around large landscapes, such as the Rocky Mountains, to develop joint policy and collaborative actions. They work hard to bring all the networks involved “around the table” -- loggers AND environmentalists, for example. Participants in such networks do not have to agree on much, only join together with subsets of the network on projects and sub-projects that serve their interests and priorities.

Networks of networks with different focal areas. This occurs when a network intentionally reaches out to a network with a different purpose or focal area to expand their understanding.

Leadership Learning Community (LLC) recently convened people from a number of different networks in Oakland California. During the gathering a racial justice network interacted with more traditional health organizations, and both benefited greatly from each other’s perspective. In St. Paul Minnesota, a network of public libraries began working with networks working to support homeless people. This resulted in some libraries becoming support stations for homeless individuals - installing showers, lockers and Internet access stations.

Another example is a set of networks who come together around common learning interests. For example, I work with the Resonance Network (working to create a world where all women and girls can thrive) and the WEB Network (well being and equity bridging network supported by RWJF). First the WEB Network met with Resonance to hear “lessons learned” from Resonance during their formation process. What things did they do successfully? What did they wish they had done sooner? Both networks are now sharing what they are learning as they develop Innovation Funds and facilitation pools. This network of networks is expanding as these networks query other networks on communications and governance systems.

4. In Conclusion

Networks of networks have huge potential. They encourage the kinds of aggregation and numbers that can result in successful campaigns and policy initiatives. They also can convene innovative projects from around the country (or world) to learn from each other, support each other and provoke each other to expand how they think about what they are working on.

Unfortunately, few of these types of networks of networks exist. Funders would find it very fruitful to invest in the explicit formation of networks of networks, as it could massively increase learning and impact as networks share innovations and aggregate their power.

In the free resource for this week is a diagram of networks of networks and a set of questions you can use to help your network think more explicitly about the networks of which it is a part.

Please share your stories about the type of network(s) you are involved in the comments below. Or, what type of network of network do you wish existed so you could be more effective?

Header Image by Evie Shaffer on Unsplash

9 Things Teams Need for Successful Collaboration

Across the U.S. and Canada, multi-stakeholder collaborative networks are addressing the systemic issues and wicked problems that cannot be solved by any one organization or institution alone.

In the past 5 years here at Circle Forward, we’ve been working with these collaborative networks addressing regional food security, large scale landscape conservation, public health, economic and community development, and more.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

These networks distribute their work through “circles.”

There are “circles” that maintain the strategy of the whole initiative, sometimes called a steering team, coordinating group, stewardship team, catalyst group, etc; and there are “circles” that take on specific strategies or projects, called working groups, teams, clusters, constellations, committees, etc. These circles often self-organize and have autonomy to set their own agendas, within the larger purpose of the network.

When circles within collaborative networks are operating by consent, which we recommend, they need at least 9 practices for working together effectively. (Thanks to John Buck for his support in the first version of this list!)

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

1. Purpose

A circle has a reason for existence, shared and consented to by all its team members. The team’s purpose supports the overall network’s purpose. This purpose and the values on which it is based must be codified in writing and accessible to members. Decisions are measured by how well they move the circle toward its purpose.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

2. Transparency

There must be ways for the circle to access all the information it needs to make its decisions. This does not mean that all information is available to all people all the time, especially where there are clear reasons to maintain confidentiality. At the same time, having a default position of openness to share information builds trust. It supports more equitable access to the information needed to make decisions and greater engagement.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

3. A Memory System

A circle has a mind of its own. As such, circles should maintain short-and long-term memory systems. Typically these systems take the form of a collection of documents, meeting records, and written processes and instructions that are easy to retrieve and use. It includes clear descriptions of how the network operates and how to participate.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

4. Coordination, Facilitation, and Communication

Circle participants link and work with each other, other circles, and the wider network. They need platforms for sharing information and communicating like those described in the Network Weaver’s Communication Ecosystem free download. And they need systems of support that promote access and equity of participation.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

5. Feedback

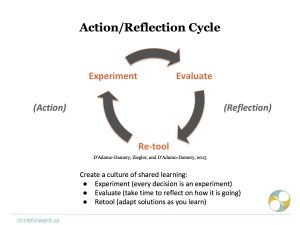

Circles improve their effectiveness by using feedback loops to gain knowledge through experience. We call this iterative, incremental approach the Action-Reflection Cycle. (Click the image for a free download)

It includes structures for assessing, measuring, learning and responding to feedback. Feedback must especially be sought from people on the margins to sustain a culture of consent.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

6. Trust

As Steven Covey observed, success in collaboration moves at the speed of Trust. Trust is built in collaborative networks when members make space for difficulty, such as interpersonal or inner conflict. They get really good at giving and receiving feedback, to be accountable to each other. Trust has a chance to develop when people accept their blind spots and listen to each other’s viewpoints. Healthy circles are social places where joy, laughter, and energy are signs of the work moving forward.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

7. Equity and Voice for Affected Parts of the System

“Nothing about me without me” needs to become standard operating procedure; in other words, people have a voice in decisions that affect them. Success in systems-level change depends on authentic participation from all parts of the system. Across race, gender, class and other differences, healthy circles learn about how cultural and historical contexts affect people. They seek to realize the highest potential in each individual. Consent-based processes give people a range of tools to operationalize equity and make wiser decisions.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

8. Emergent Creativity

Collaborative networks form because problems are wickedly complex. Healthy circles within these networks are willing to explore the complexity of the issues. They support leaders who say “I don’t know,” and are willing to enter realms of uncertainty with curiosity. They make space for different ways of knowing and honor intuition. They see the world as deeply interconnected, asking what’s really going on here; how does a small problem perhaps reflect systemic issues? They discover elegant solutions that emerge from the context.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

9. Continuous Development

Given the constantly dynamic nature of networked organizations, circles need a great deal of flexibility in relation to their environment. To respond effectively, collaborative teams must develop continuously. Development means learning, teaching, and researching in interaction with the common purpose. It means being open to change, including personal change, as a result of what we learn and experience.

As part of their development, circles need to think about succession. They need processes to add and remove members and processes to easily assemble and disassemble their circles.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

When woven together with the keystone principle of Consent, these 9 areas of practice will keep your collaborative governance network “circling forward.”

Originally published on January 27, 2019 at CircleFoward.us

Inclusive Networks Are Shaping Our Lives Right Now - Are They Governance?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]About six months ago I was introduced to a deeply remarkable development – and its even more profound implications – by two people who didn’t know each other and with whom I’ve talked in depth almost every week since then.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]This development electrifies me. I have long felt that achieving effective, inclusive, decentralized governance would require a major, perhaps insurmountable effort. But these two folks have opened my eyes to an unexpected form of such governance manifesting right now all around the world.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]What is that emerging inclusive, decentralized form of governance?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

COMPLEX INCLUSIVE NETWORKS AS GOVERNANCE

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]These new friends pointed out rapidly increasing activity of networks that embrace

- multiple sectors (public sector, private sector, and civil society)…

- multiple stakeholders (diverse parties involved in various issues and systems)… and

- multiple scales (ranging from local to global).

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]They shared their thrill at seeing this complex activity emerging as a new form of whole-system engagement and governance that could transcend governMENT as we’ve come to know it. (See the examples and analyses referenced at the end of this email.)

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]My companions in this new inquiry and sense of possibility are Tracy Kunkler and Steve Waddell. Both work with transformationally oriented stakeholder networks, Tracy mostly with local and regional systems, Steve at all levels including global networks self-organizing around the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

SOME BIG QUESTIONS FOR THE BIG PICTURE

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Last month, at the Frontiers of Democracy conference in Boston, Steve, Tracy and I presented a session entitled “How Do We Midwife the Emergence of Wise Governance Networks?”

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Our session description asked a few additional questions:

- Are you sensing new patterns of societal governance in multi-sector networks?

- Are they more diverse and adaptive to the scale and pace of change than governments?

- Might they become powerful governance structures, growing to include government, but also transcending it?

- How can we influence the emergence of these to be democratic, powerful, and wise?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Note that by “governance” we don’t mean governMENT (although that’s part of it), but ALL the things groups, organizations and institutions do to shape what happens on the ground to deal with societal issues and goals and how our collective lives unfold.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Of course when we look at what governMENTs do, they definitely impact that. But so do businesses and civil society groups. So when a network involves players from the public sector, the private sector, AND civil society, we are talking about a multi-SECTOR network.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]And if we look at issues (like poverty, human rights, or climate change) or at social systems (like food systems, health care systems, or educational systems), and we find that groups across the spectrum of roles and perspectives are trying to work together to have some kind of shared impact on the issue or system they’re all part of, we are talking about multi-STAKEHOLDER networks.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]And if any of these include players at various different levels of functioning – local, state, regional, national, international, global, etc. – we are talking about multi-SCALE networks.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]These are not so much networks of individuals as networks of groups, organizations, and institutions. When they begin to weave together into multi-sector, multi-stakeholder, multi-scale (MS3) networks, they become increasingly inclusive, often by asking “Who else should be part of this work, this conversation?” With true inclusiveness, the level and texture of impact they have – and could have – begins to boggle my mind. They present the possibility of millions of committed eyes, ears, heads, hands, and hearts working together on the ground in every aspect of any given issue or system. (If you are concerned about the possible totalitarian implications of this, please see my asterisked* note below.)

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]And IF they are actually working together effectively – addressing concerns, developing shared goals and standards, seeing beyond narrowly framed interests – what we have is a whole new level of whole-system governance of, by, and for whole systems. By being part of groups who are part of these networks, whoever is involved in a collective challenge or vision can be engaged in addressing it. A tremendous amount of competence, passion, and knowledge can be tapped for positive evolution in that realm – indeed, in all realms.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]At least that’s the vision I glimpsed, and it hooked me.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

PROVIDING A KEY MISSING INGREDIENT

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]When we asked the attendees in our workshop what they were experiencing in their networks, they told us that the unprecedented diversity of the participants was showing up as a real problem. These networks include people from different cultures and worldviews (think governments, businesses, and nonprofits), different sides of various issues, different constituencies, and so on, quite in addition to different demographics, experiences, organizational styles, and more….

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]I realized that many people in the networks I’M connected to – facilitators, mediators, organizational consultants, process designers, conveners, community organizers, and so on – have tremendous know-how that can help people work creatively across differences. (Much of this expertise is reflected in the wise democracy pattern language, most notably in the pattern “Using Diversity and Disturbance Creatively” but actually throughout the pattern language.) Since these roles form a professional category that specializes in helping different people work together effectively, I realized that those professions are a vital ingredient for the successful emergence of this new whole-system form of governance. That role urgently needs to be acknowledged and strengthened as a factor in how all this unfolds.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

WHAT ABOUT WISE DEMOCRACY?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Talking about all this as a new form of governance immediately raises the question of where We the People are in all this – where are we, the citizens … we, the communities? What is our role and our power? Where exactly do we – or should we – fit in this new governance picture? What public answerability should stakeholder networks have – and vice versa? Should citizen deliberative councils play a major role in focusing the goals of stakeholder networks or reviewing their activities? Might crowdsourcing solutions or priorities engage the public in issues being addressed by stakeholder networks that require whole-community involvement? (Note that Citizen/Stakeholder Balance was part of the wise democracy pattern language long before I met Tracy and Steve.)

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]This focus on stakeholder networks also raises – for me – the question of how we can increase the likelihood that the results of such coordinated whole-system activities are wise. To what extent will these networks take into account what needs to be taken into account for long-term broad benefit? How can we ensure that oft-overlooked sources of wisdom get included in stakeholder network deliberations?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]I’ve been asking such questions for years as my “wise democracy” vision has developed. I have some thoughts about possible answers, but those thoughts are barely a beginning. Fortunately, people like Tracy and Steve also find these questions compelling, realizing their importance if this emerging governance-through-inclusive-networks phenomenon is going to end up being an actual long-term blessing.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

TWO IMPORTANT PIECES OF WISDOM

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Two big-picture insights about these questions can help guide our thinking.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]1. First of all, the diversity and scope of the people and groups involved – IF they are truly inclusive and successfully working together – automatically means that a wide range of perspectives, experiences, interests, needs, and information will be taken into account. It is only by including these and taking them seriously that the people in these diverse networks will be able to function well together. And, in doing so, they will inherently be taking into account much of what needs to be taken into account. Because of the diversity of concerns and needs considered, these networks will realize “what’s needed for long-term broad benefit”, thereby moving us a long way towards collective wisdom.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]2. Secondly, advocates of deliberative democracy have pointed out complementary roles for citizens and stakeholders who function as experts, as embodied in the formula Experts should be on tap, not on top. This formulation is supported by cognitive science that recognizes that facts and reason cannot themselves lead to a decision. They can provide us with much understanding of what is going on in a situation, but in order to make a decision we have to WANT something – which necessarily involves our desires, feelings, values, and needs. Although these can be defended by reason, they can’t be derived solely through reason; they are fundamental. So in a democracy it is the people’s needs and dreams, the community’s values, the common interest that should properly guide decision-making, not experts.

Yes,we the people need the advice of experts like stakeholders and researchers to help us understand the actual conditions and dynamics of life well enough to satisfy our needs and manifest our values in the complexity of the real world. But WE ARE the ultimate experts regarding our needs, our values, our longings, and our everyday experience.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]So there is potential for tremendously effective wisdom to emerge from the dense diversity and broad reach of inclusive stakeholder networks and the kind collective wisdom about which the wise democracy pattern language offers so much guidance.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]The inquiry into this prospect, and the work to raise our awareness of it, have just begun. I’d like invite you into both of these. What are your thoughts? What do you think should be attended to and done? What role(s) might you play? Let me know.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]Coheartedly,

Tom

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]* Networks for surveillance and control are necessarily top-down. What I am talking about here are self-organizing networks of diverse groups and organizations trying to work together. They are not networks of individual agents working at the street level for centralized power. Multi-sector, multi-stakeholder, multi-scale networks are complex, multi-faceted systems that do not lend themselves to oppressive control or co-optation by central authorities, although attention is warranted to ensure that remains true as network governance evolves.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]

REFERENCES FOR EXPLORING EMERGING INCLUSIVE NETWORKS AS GOVERNANCE

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Metagovernance of Governance Networks

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Multi-Stakeholder Initiative Database

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

New York’s Juvenile Justice System

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

“Global Governance Enterprises: Creating Multisector Collaborations” (2016)

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

“Multi-stakeholder Processes for Governance and Sustainability: Beyond Deadlock and Conflict” (2002)

[ap_spacing spacing_height="45px"]

Orignially published at tomatleeblog.com on July 9, 2017

[ap_spacing spacing_height="45px"]

We encourage you to comment on this post so we can hear about your thoughts and experience.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="60px"]

Sociocracy: Why, What and Who?

An excerpt from Chapter 1 of Many Voices One Song: Shared Power with Sociocracy by Ted J Rau and Jerry Koch-Gonzalez

Sociocracy is a set of tools and principles that ensure shared power. How does one share power?

The assumption of sociocracy is that sharing power requires a plan. Power is everywhere all the time, and it does not appear or disappear - someone will be holding it. We have to be intentional about how we want to distribute it. Power is like water: it will go somewhere and it tends to accumulate in clusters: the more power a group has, the more resources they will have to aggregate more power. The only way to counterbalance the concentration of power is intentionality and thoughtful implementation.

Power, like water, is neither good nor bad. In huge clusters and used against the people, power will be highly destructive. Used to serve the people and the earth, distributed to places where it can work toward meeting the needs of the people and the earth, power is constructive, creative and nourishing like an irrigation system.

One can think of sociocratic organization as a complicated irrigation system, empowering each team to have the agency and resources they need to flourish and contribute toward the organization's mission. We avoid large clusters of power, and we make sure there is flow. Water that is allowed to flow will stay fresh and will reach all the places in the garden, nourishing each plant to flourish. Sociocratic organizations nourish and empower each team to have the agency to flourish and contribute toward the organizations' mission.

Power does not have only one source. In that respect, power is different from an irrigation system. All members of the organization feed their own agency and resources into the organization, in each team. Everyone contributes their power and relies on each other's power. From there, power, and with it, resources, gets distributed into the whole and gets channeled to where the group wants to put their energy. Sociocratic organizations keep everyone's own agency and power intact and support people to make changes bigger than they could have made alone.

In order to achieve this, our sociocratic organizations differ from organizations with aggregated centralized hierarchical power in two ways:

- We distribute power more evenly. Those who come with less agency get support to step into more agency. Those who come with more sense of agency contribute toward the whole without diminishing anyone else's power. Teams doing work together are empowered to contribute. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- We let power flow. Flow means the distribution of power needs to be adjusted and potentially changed over time. The sociocratic organization is adaptable and resilient.

Building a system that distributes power by empowering everyone requires thought and intentionality. That is what sociacracy is: the design principles of distributing power in a way that flows with life.

1.1 The values under sociocracy

What kind of world do we want to live in? The way we answer this question is: We want to live in a world where people support each other, consider each other and help each other meet needs. A collaborative world.

1.1.1 Organizations are living systems

Organizations are designed in a way that fosters our connection with each other and with ourselves, both within and outside of the organization. To effectively create connections, organizations need to be life-serving and all-embracing. Life-serving means that we want to foster organizations that work for everyone in the organization and hold care for everyone affected by the organization. No one and nothing can be ignored if we want to honor connection.

We want to support living organizations. Living systems can be on any kind of scale: a cell is a living system as it creates a membrane, forms an identity and interacts as a whole with its outside. Organizations are living systems: they interact with their outside (clients, students, consumers, investors), and their members on the inside interact as information, goods, and energy are being exchanged. A system that does not let the organization breathe like a living system will constrain and muffle its unique expression of life. Living systems have characteristics that we want to be aware of:

- Living systems form a whole and can act as a whole. For example, a human body is a complex system of smaller complex systems, but it is perceived and acts as a whole.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Living systems are interdependent with their context. There are no isolated systems. However, many people in Western cultures have been conditioned to think individualistically, as if we were separate from our context and could ignore our impact on the world around us.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Living systems are interactive and open (within limits). An organism that does not interact with its outside will not be able to survive. Organisms provide a (permeable) "membrane" between their inside and their outside. This is the basis of identity and capacity to act.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Within a system, parts are interdependent, which means they rely on each other to meet their needs. This both true for parts of a cell and it is true for a society.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Living systems are dynamic, they are not static. They change over time as they adapt and change constantly. Living systems can learn and heal. They are resilient.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Living systems are inherently ordered, in their own way. A forest, for example, has an order. So does an organization - living systems are defined by the fact that they create more order than is present in entropy of their surroundings. Organizations do exactly that: organize to exchange information and resources to meet needs.

Purchase Many Voices One Song HERE.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

We encourage you to comment on this post so we can hear about your thoughts and experience.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

featured image by: Mel Poole