NETWORK VALUES

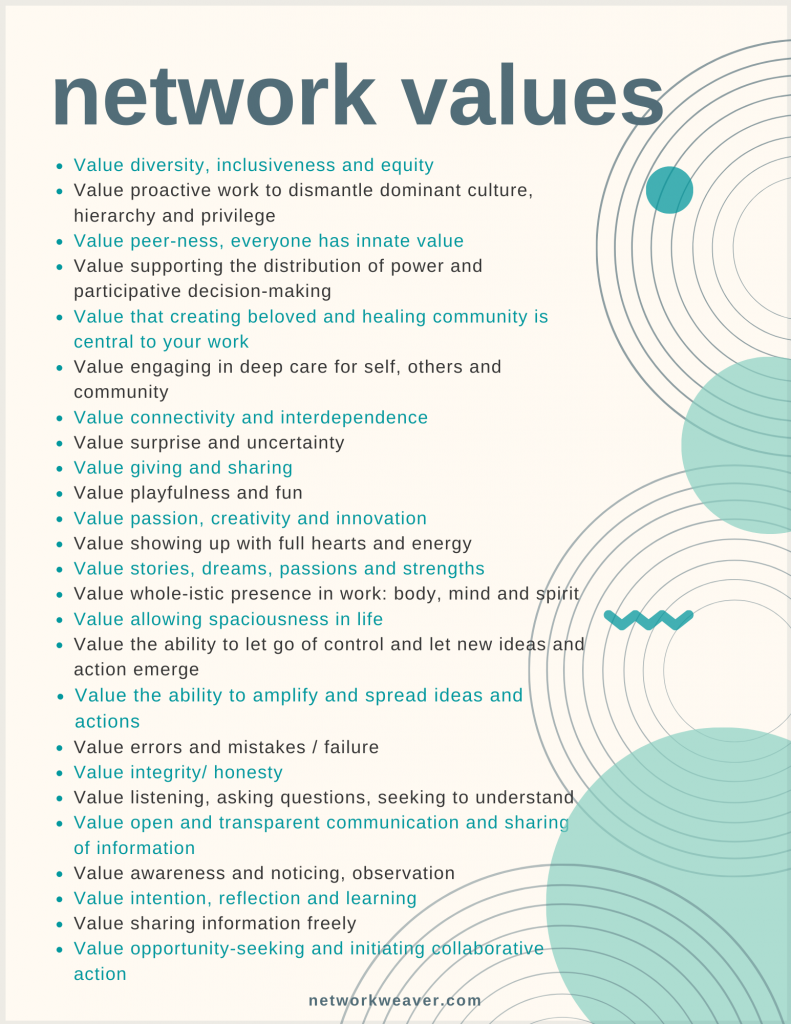

Having a group or network take a values survey raises awareness of the values and behaviors that enable networks to be system shifting or transformational.

Network Weaver has published a Network Values Module. Within this module are links to two web-based network values surveys, along with instructions. Also included are printable versions of the network values surveys and a printable flyer of a compiled list of Network Values.

Download the free module HERE

PURPOSE OF NETWORK VALUES SURVEYS

The purpose of having a group or network take a values survey is that it raises awareness of the values and behaviors that enable networks to be system shifting or transformational. It also gives clear information about the specific value areas where they need to work together to help each other shift to more network ways of being. People take the survey, immediately see the aggregated results, and work together to develop strategies for shifting challenge areas.

It’s extremely valuable for groups of networks to take the survey every six months (or even more often at first) so that they can see the progress they have made in shifting to network values and identify areas that still need attention.

There are two values surveys in this module.

- #1 Network Values Checklist

- #2 Network Values Dashboard (for individuals and organizations)

The first one is for individuals. It is used to help individuals identify the areas where they are already behaving from network values. You can have the group aggregate the results of everyone who took the survey so that they can see to what degree they as a group or network have shifted to network values and behaviors.

The second survey has two versions of each question. The first asks the individual about their values. The second asks the individual to rate how their organization ranks in reflecting this value or behavior. Usually the participants will score higher than their organizations. This survey helps people recognize that they cannot simply shift their own values, but need to work with their organizations to shift the entire organizational culture – if they want to be transformative in their impact.

Download the Networks Value Module HERE

DECENTRALIZED NETWORKS PART II: THE REVOLUTION WILL BE BUILT ON TRUST

Read PART I: Decentralized Networks And The Black Radical Tradition: From Collective Organizing to Building Black Futures. HERE

In this month’s feature, Kei Williams shares their “activating moment,” touches on movement building tools and shares their admiration for structural networks that are not only principles-based but continue to grow and meet the needs of the community. Material for this blog was compiled and transcribed by Sadia Hassan from the Decentralized Networks and the Black Radical Tradition community of practice gathering in March, 2020. You can find the video of this presentation HERE.

Kei is a queer transmasculine identified designer, writer and public speaker. A founding member of Black Lives Matter Global Network, Kie’s work is to transform global culture towards the systemic analysis of structural racism. As Movement Net Lab’s StrategicNetwork Mobilizer, Kei creates powerful conceptual and practical tools that factor in the growth and effort of the most dynamic and emerging social movements of our time. Kei is also the Lead organizer for Safety Beyond Policing, Swipe it Forward, and Trans Liberation Tuesday.

Kei aims to use their platform to center communities who identify as queer, trans, gender non-conforming, and those living with mental illness. Before the lockdown, Kei was active in engaging communities in the Black Gotham Experience, an immersive visual project exploring the impact of the African Diaspora on New York City.

ACTIVATING MOMENT: HOT SUMMER OF 2014

Every organizer has an activating moment, a political event that pulls them out of the mundane rituals of everyday life into a political awakening. For Kei, it was the Ferguson Rebellion. A rebellion which spanned months and sparked protests in other cities. The rebellion, which resulted from the state sanctioned murder of Michael Brown, was the first time Kei saw America attacking its citizens in a hyper-militant way in response to young folks rebelling against police shootings.

LANGUAGE MATTERS: REBELLION VS RIOT

Ferguson is often called an uprising or a riot, reducing the well-organized and strategic collective actions of protestors to the haphazard and agent-less language of “violent unrest.” For Kei, the word rebellion honors the risk of organizers who choose to build community under surveillance as they continue to fight in the street against the state. Historically, the state has considered the rebellions of enslaved BIPOC people as disconnected from the systemic violence they endure in their everyday lives. One reason the Black Gotham Experience has been so important to Kei is precisely because it connects the struggles of enslaved folks who rebelled in 1712 and 1741 against the institution of slavery and Wall Street to the current collective struggle for Black liberation, what Marc Lamont Hill calls “a principled, righteous rebellion.”

COLLECTIVE ORGANIZING IS A BLACK RADICAL TRADITION

Ferguson benefitted so much from organizing that was already being done by local Black Lives Matter chapters operating loosely in various cities in response to police shootings in 2012/2013 (Trayvon Martin, Rekia Boyd, Shereese Francis). What Kei saw in the three to four years of organizing with the Black Lives Matter Global Network was that movements have to be guided by principles, strive to create cultural change, and bear a rallying cry (Black Lives Matter, 99% vs 1%) that appeals to communities under attack. As a young organizer, Kei has appreciated stepping into the radical traditions that were developed by Black Lives Matter and the lessons learned from the Occupy Movement, chiefly that it’s important to foreground what is being fought for as much as what is being fought against.

Questions to ask as you lean into organizing:

- What exists beyond the moment?

- What does it mean to be in solidarity with each other?

- What are we fighting for/towards that’s gonna be a transformative system?

THE FUTURE OF THE DECENTRALIZED NETWORK

BLM NYC Chapter helped create a lot of the structural webbing for the Global Network. People like Allen Frimpong, Arielle Newton, Monica Dennis had been working with June and other decentralized Network Organizers to determine what the structure of the Global Network was going to look like and what was power going to look like in all of these different places. We have a history of hierarchical structures in organizations but it takes radical imagination to have a decentralized network that is uniform but can grow to scale.

Questions to ask when building decentralized networks:

- What does a decentralized structure look like?

- What needs to be done differently?

- How can we grow it to scale?

- How will we know when to keep it localized?

- What is power going to look like?

- Where am I? Where am I going?

- Where do I/my skillsets fit in?

ORGANIZING HAPPENS THROUGH RELATIONSHIPS

You have to have trust and good relationships for any organizing effort to work.

In 2014, organizers learned that detainees in the Federal detention center (MDC) didn’t have heat and were being kept in their freezing cells in the middle of a polar vortex. Two close friends called Kie and asked them to come down. Kei felt compelled to show up as a movement organizer and friend because of the relationships they had built. Over fifty people joined the action and occupied the parking lot, staying for 3 weeks. People slept in tents with propane heaters. Medics signed up to wake folks up every thirty minutes.

What came out of that small occupation was a sense of solidarity and a network build-out of medics, emergency responders, family and friends who continued to organize for detainees at MDC. People were brought in based on how they fit, what skills they offered, who they were connected to and could support.

Some principles of Decentralized Networks that create cultural shifts and community action:

- Relationship & Culture of Trust

- Looks like: building a culture around trust and communication

- Self-Organizing:

- Looks like: a culture of empowerment, self-determined and innovative work flows

- Structure and support:

- Looks like: twitter hashtags, cultivating alternate/virtual convening spaces (slack, mighty networks, etc), liberating structures, learning pods

NO NEW JAILS NYC CAMPAIGN:

BLM NYC and a lot of other collectives came together and created a de-centralized, multiracial, intergenerational network. First order of business was to create a network mapping to map the people who were in the room and what they wanted to see.

One of the accomplishments of No New Jails NYC is the conversation about abolishing jails and releasing incarcerated people that have become amplified during the pandemic. The demand came from decades of organizing as black and brown people and is abolitionist in principle. The current campaign that brings them all together is the Free Them All for Public Health campaign. Culturally, there was already a framework and a cultural language that influenced the Free Them All for Public Health campaign which began with #CLOSErikers in response to Khalief Browder’s death and now in response to Covid19.

Free Them All is going global, to focus on incarcerated people worldwide. The first thing it did when the pandemic began was lead a soap drive with jail and prison abolition networks. They understood how covid19 was going to face huge risks because the state of the jails are inhumane. Decentralized organizing means trying to look at things as a hub of demands and circles of support. It’s important to get plugged into mutual aid but as network and movement builders we have to lean in and build other movements. We have to find the scaffolding where movements overlap and maximize impact.

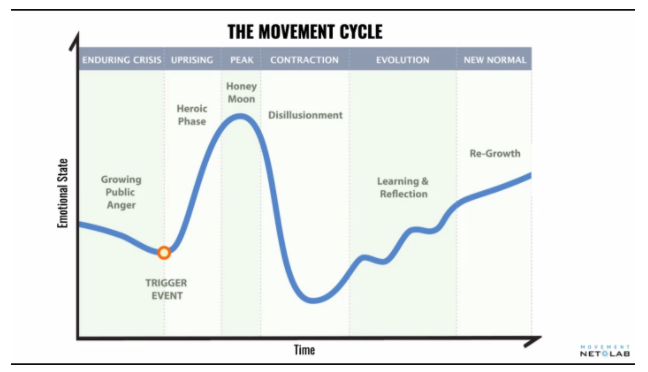

KNOW YOURSELF, KNOW THE CYCLE

As “networked social movements” continue to transform the political landscape, Kei emphasizes that Movement Net Lab has grounded their language, curriculum, design sense, and style in how they approach decentralization. Here is a map they’ve provided that illustrates the flow of a movement cycle so we can better map our interventions alongside it’s ebbs and flows.

It’s important to know the constant flow of a movement cycle.

1. Urgency overlaps with a sense of history → Trigger moment: Eric Garner → Heroic Phase: we’re gonna win → Honey Moon: action, in the streets/protesting, sweet moment where anything feels possible→ Disillusionment: didn’t get the demand → Reflection: what we learned, who we worked with, shouldn’t work with → Regrowth: what now?

2. Movement cycles allows us to map and build off of legacies that have existed for a long time

3. Knowing the movement cycle helps clarify where our skills best fit and where interventions can be most effective

If you have any questions, concerns or corrections, or to pitch a blog post please email us at networkweaverblog.com.

watch the video of the session by downloading the free resource HERE.

About the author:

Sadia Hassan is a facilitator and network weaver who has enjoyed helping organizations use a human-centered design approach to think through inclusive, equitable, and participatory processes for capacity building.

She is especially adept at facilitating conversations around race, power, and sexual violence using storytelling practice as a means of community engagement and strategy building.

She is an MFA candidate in Poetry at the University of Mississippi and has a Bachelor’s degree in African/African-American Studies from Dartmouth College.

HEALING MEANS JUSTICE MEANS HEALING

This article on systemic change and restorative justice was written and published by The Bramble Project on April, 19th, 2020 – prior to the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests.

WHAT WILL IT TAKE TO STAND IN THIS OPPORTUNITY FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE?

Disclosure & disclaimer: Some projects mentioned here are partly funded through Seattle’s Equitable Development Initiative, where I work. Views expressed here are my own, not my employer’s.

The data trail of racial wealth and health disparities in the path of COVID-19 is a story of deep injustice. But not the complete story.

Just as high blood pressure lets us know something needs to change, but can’t show us how to be well, we need to look through our data with deep intuition in order to re-imagine the future we want.

Let me paint a story of a healed future. This story asks those with resources and institutional power to drop what we think we know. It asks those waiting for change to stop waiting. The change we yearn for won’t begin from above. This future is already being born, and it invites you to choose which story you’ll be a part of.

We must be clear: justice does not mean catching Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) up to a broken system. Injustice is only a symptom of deeper toxins that hurt us all. Long before COVID-19, communities deeply experienced with displacement, untimely death, social stigma, financial instability, and health disparities have also held wisdom in healing this toxic soil. Justice means supporting their leadership, and doing the work to catch up to them.

1. HEALING THROUGH RESTORATIVE JUSTICE

All life on Earth today, from bacteria to bananas to baboons, share a common ancestor in LUCA, a microbe that lived four billion years ago. Try strolling around town with that perspective, and you’ll see right away that we humans are close kin.

Maybe we manage to fuck each other up not because we’re so different, but rather because we’re family.

THE DISEASE OF US-AND-THEM

In My Grandmother’s Hands, Resmaa Menakem traces the brutalities that Europeans had inflicted upon each others’ bodies long before they landed, still unhealed, on this continent. (If the notion of trauma stored in bodies, and not in brains alone, is new to you, look here or here for more. White men putting down their own dancing is just a small example of how dominant-culture bodies can hold trauma through deep body armoring.)

Unhealed trauma spreads. My mom’s body, for example, carries the memory of Cultural Revolution shamings. Her shoulders bore household responsibility at age twelve. Her eyes have witnessed public mutilation. My dad’s belly remembers starvation. His spine still carries a commitment to leave and make a better life for his family.

My body learned their stories. My gut knows the pinch of not fitting in. My throat carries words gone unheard. My muscles hold a fear of lashing out. Somatic therapy has shown me that behaviors I’m often rewarded for—intellectualizing, refusing to surrender, disguising my needs—have been compensations for unprocessed trauma.

As Menakem writes:

“Unhealed trauma acts like a rock thrown into a pond; it causes ripples that move outward, affecting many other bodies over time. After months or years, unhealed trauma can appear to become part of someone’s personality…. And if it gets transmitted and compounded through multiple families and generations, it can start to look like culture. But it isn’t culture. It’s a traumatic retention that has lost its context over time.”

There is trauma in what we call oppressive power. Hoarding ownership and resources is not the behavior of healed, well-connected bodies. Escaping into intellectual strategy, and attempting to predict and control the unknown, is also a systemic trauma.

We can only heal by choosing what Menakem calls “clean pain” over the continuation of centuries of “dirty pain”:

“Clean pain is pain that mends and can build your capacity for growth. It’s the pain you experience when you know, exactly, what you need to say or do; when you really, really don’t want to say or do it; and when you do it anyway. It’s also the pain you experience when you have no idea what to do; when you’re scared or worried about what might happen; and when you step forward into the unknown anyway, with honesty and vulnerability….

“Dirty pain is the pain of avoidance, blame, and denial. When people respond from their most wounded parts, become cruel or violent, or physically or emotionally run away, they experience dirty pain. They also create more of it for themselves and others.”

From this description, it’s easy to see that dirty pain criminalizes Black and brown bodies, and maps property values to land stolen in genocide. But there’s more.

It’s our own dirty pain that rewards political candidates for crushing their opponents onstage. Our dirty pain mutinies when leaders fail, even when failing is the only way to learn what comes next. Many institutions that can survive in this ocean of dirty pain are so well-defended under duress that, even in a catastrophe, they won’t admit to what they can’t know.

Sadly, many powerful institutions have learned to deliver authority without vulnerability. They are too well-protected to lead us in healing.

HEALING WITH VULNERABILITY

If you’ve grieved a loss, you know that healing is messy. It can feel like going backwards for a long time. It takes time for wisdom and insight to emerge. This is why adrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategy and Pleasure Activism are such important works. We don’t know exactly how to heal collectively, but we can take it one step at a time, guided by the wisdom of nature’s bodies.

Trauma isn’t the only stone that ripples outward. Here are just a few examples of how healing is also rippling all around us.

The newly opened Restore Oakland building centers the wisdom of restorative belonging and agency, held against generations of unjust criminalization and economic injustice.

Locally in Seattle, Queer the Land is learning from the frequent displacement of queer, trans, and Two-Spirit BIPOC to take an emergent and adaptive approach to cooperative land stewardship—not ownership, they stress, because this is Duwamish land.

The 40+ partners at Black & Tan Hall pay critical attention to maintaining relationships, with white partners caucusing regularly to become better allies. The venue will be based in art and food, two experiences that remind us that our gifts have more value when they’re shared.

Nile’s Edge, a black-owned afro-centric healing arts center in the Central District, opened last year after one of its co-owners took a real estate training program and realized that development finance isn’t rocket science, and in fact often doesn’t make sense (more on that in the next section).

The Chief Seattle Club continues to care for homeless urban Natives during the COVID-19 crisis. As Executive Director Colleen Echohawk writes:

“Native people know what to do in these stressful and extreme situations. We take care of each other. We intentionally look for the most vulnerable in our community. We comfort them and lift them up.”

For more on the perspective and lineage of restorative justice, check out this podcast episode with Kazu Haga and Carlos Saavedra.

2. JUSTICE THROUGH RESTORATIVE ECONOMICS

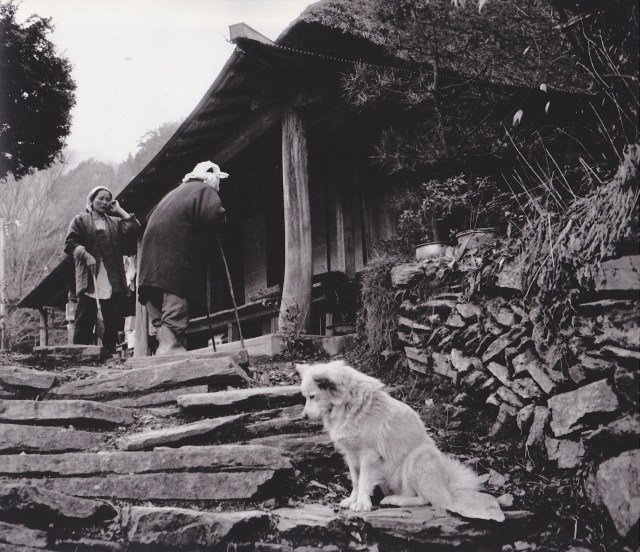

Today, a few thatched roofs remain as tourist destinations in Iya Valley, Japan.

A newly thatched roof can last 25 years. Back in the day, the roughly 25 families in each hamlet gathered every November to harvest enough thatch for one roof, rotating to keep each roof thatched just in time.

In the 1970s, as more and more young people trickled out to Osaka, this economy of collective care began to fall apart. By the time I moved there in 2005, roofs had long been covered in metal. Nearly 40% of jobs were in public works construction. Truckloads of concrete entered the valley, and truckloads of timber left.

This is the paradox of what we call economic growth. Villagers harvesting thatch for each other doesn’t count towards GDP, but when fractured social bonds force the remaining families to cover their roofs with tin, that gets tallied as growth. Growing enough food to share with neighbors doesn’t show in our economic data, but working a construction job to buy food trucked in from a distribution center does. This numerical accounting is what Charles Eisenstein calls converting the gift into money, and what Just Transition movements such as the Green New Deal call an extractive economy.

THE DISEASE OF NOT-ENOUGH, PART 1: FRACTURE

As a toddler in China, I remember grown-ups telling me how fortunate I was that my parents had left for the US. After having lived through poverty and violent revolution, leaving to pursue opportunity must have been an inevitable choice for them, one I might never know in my own experience.

What I have observed from experience, though, is that uprooting from community seems to make hoarding more appealing. When collective care is not reliable, we suddenly need more than we actually need.

Social fracture can encourage worse than a little hoarding. Research finds that the more anonymous we are, the likelier we are to “defect”, choosing to take advantage, betray, or hoard rather than cooperate. Repeated exposure to this can establish a culture of defection—academic lingo, perhaps, for an extractive economy.

It’s clear how extraction has disproportionately harmed BIPOC communities. Student loan debt, private prisons, displacement, and the health impacts of industrial pollution are only subtler when compared with outright slavery and land theft, yet devastating nonetheless. During this pandemic, predatory buyers are already scouring for land deals.

Nobody truly wins in extraction. For the 76% of Americans who rent our homes from landlords or from banks with a mortgage, it’s often economically impossible to slow down, to take a health break, to use a crisis as an opportunity to reconnect with our wisdom and intuition. Even those with stable jobs don’t necessarily find them fulfilling. Meanwhile, the loneliness epidemic has intensified, hitting 61% of Americans last year before social distancing.

The thing is, most of what we accumulate doesn’t help us in a catastrophe. Properties and financial assets are mostly social constructs, buttressed by legal contracts and insurance policies. Our brains and talents are pretty useless alone. What sustains humanity in a crisis are the relationships that we nurture. Rich relationships are the fertile soil in which shared wealth and ideas can flourish.

THE DISEASE OF NOT-ENOUGH, PART 2: GROUPTHINK

As a landlord, I’m learning how easily our extractive culture can override a more intuitive approach to relationships.

In 2012, I bought a small condo right before the market upswing. I eventually moved in with my partner, but the condo had a piece of my heart.

Not ready to sell it, I decided to rent to people who could no longer afford to live in the neighborhood. I’m transparent about finances with tenants, and they agree on what they can pay. When their situation changes, as with COVID-19, we work it out month by month.

What I’m doing isn’t difficult, financially. I’m more than covering my costs. But being a landlord has tested my values.

Since the 1300s, “value” has meant both price (like the value of a house), and worth (like the value of having a place to live). The equivalent “价值” took on this double meaning in China by the 1700s, and in Japan by the 1800s.

This linguistic invention can be a trap when monetary value and emotional value pull in opposite directions. In a society that built high monetary value on land and labor that was stolen through murder, abuse, and betrayal, conflating the two into a single number can feel like systemic gaslighting.

I think this conflation, at a more subtle level, tricks good people into choosing transaction over relationship when they become landlords. When I go against market wisdom, I can feel doubtful and insecure. But if we can escape the trap of conflating monetary value with emotional value, we can then use the gap between costs and “market value” to value relationships and collective care.

Let me be clear: I’m not living cutting-edge non-extraction yet. I’m still claiming a condo built on stolen land, and I’m still collecting rent. What’s more, systems modeling predicts a ceiling to economic growth despite innovation. Factor in the restoration of over-extracted resources and communities, and many thinkers are joining what major religions and philosophers have said: non-extraction doesn’t only mean below-market returns. It can likely mean 0% or negative returns. I’m only just now, researching for this essay, letting this understanding sink in as a landlord.

My point here is exactly this: it’s difficult for institutional power—in my example here, a property deed and relative fluency in real estate finance—to implement justice well. We can think we’re doing well, but power often puts us too close to the assumptions of a failing system.

This is also why change is unlikely to begin in institutions, and why relationships matter. Working across different experiences of power helps us discern wisdom from groupthink.

HEALING WITH RELATIONSHIP

Fractured social bonds played a role in growing this extractive economy, and healed relationships must be on the path to restoring a just economy. Justice must be co-created from the ground up.

Thunder Valley CDC, a regenerative community in the Pine Ridge Reservation, is about reclaiming traditions. “Lakota Community Wealth Building,” writes Stephanie Gutierrez, “is about loyalty to place and to our people, with ownership held by the community, working with each other as one, considering each person and their ability to be part of the economy, and seeing our economy as circular where everything is connected— consciously recreating sustainable communities.”

To zoom in on how they work, consider the design of their chicken coop. Sometimes designs can look different on paper. After construction had already started, a community member noted that the building was looking a little bland, so they added colorful geometric patterns to it. Unremarkable, right? But in hot real estate markets, schedules and budgets have to be tightly accounted for. There’s rarely room for on-the-fly co-creation, so we sacrifice these simple opportunities for a sense of collective ownership.

Locally in Seattle, the Race & Social Equity Task Force began when community groups from Southeast Seattle, Chinatown-International District, and the Central District joined forces in response to displacement risk. One task force member says they’re standing on the shoulders of the Gang of Four, whose legacy of stewardship includes Daybreak Star Center, the Black Student Union of UW, El Centro de la Raza, and InterIm CDA. Larry Gossett, the surviving member of the Gang of Four, continues to uphold the power of cross-cultural solidarity.

As another example of solidarity, Real Rent Duwamish offers a small way for Seattleites to chip in on our impossible debt to the Duwamish Tribe and its ongoing stewardship of these lands, and to support whatever comes next for the tribe.

The Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition is implementing community-led Superfund cleanup that centers environmental stewardship and economic justice. Their work in building community resilience is based in a belief that collective ownership and decision-making is a critical component of resilient development.

Many organizations in Rainier Beach are working together, cross-generationally and systemically, to implement a neighborhood plan intended to fight displacement through a local food economy.

And a group is forming to adapt the Boston Ujima Project’s model locally, a way for communities to invest in collective planning through equitable investment tranches where high-wealth members contribute loan loss funds so that lower-wealth community members can earn higher (3%) returns at the lowest risk.

For more on restorative economics, see this talk by Nwamaka Agbo.

3. HEALING IN THE TIME OF CORONAVIRUS

I’ve only scratched the surface of all that’s happening in BIPOC communities to build a just future. There are experiments in the arts, housing, small business, health, immigration, environment, and more. If you’re inspired, please reach out. I love learning and connecting people with one another.

There’s a lot to hope for. But to be honest, I think we’ll mostly squander the pain that has brought us this close to systemic reckoning.

Here’s what it would take, instead, to capture this moment of opportunity to build our system back stronger.

WITH OUR HEADS: STEER OUR IMAGINATIONS TOWARD A NEW NORMAL, NOT THE OLD NORMAL.

“Our pre-corona existence was not normal other than we normalized greed, inequity, exhaustion, depletion, extraction, disconnection, confusion, rage, hoarding, hate and lack. We should not long to return my friends. We are being given the opportunity to stitch a new garment. One that fits all of humanity and nature.” —Sonya Renee Taylor

When we get a bad cold, we need to first recover, then carry on. When we get heart disease, we must not carry on, but rather reinvent our lives. Like the virus itself, this pandemic represents both: a crippling illness, made catastrophic when combined with our society’s underlying sickness.

If we speak only of the infection, and not of the heart disease, we will take wrong action. If we speak of racial justice only as righting the data, and not re-imagining the system, we will spend time and money resuscitating a dying system—energy better spent grieving, and imagining the new.

People with what we call privilege are often, in fact, a few generations behind in recognizing the gravity of our collective disease. This is why hierarchies of existing power are generally not the ones to know what to do right now. To capture this moment is to pour back resources to support BIPOC communities who best know the system’s failures and opportunities.

Will we seize this moment to admit to all that we don’t know?

WITH OUR HEARTS: SHARE POWER OUT OF GRATITUDE AND LONGING, NOT OUT OF GUILT OR GENEROSITY.

“How do we then use this crisis as an opportunity to figure out how to deeply invest in those communities, those community leaders, that are really trying to figure out how we create an economic model that is actually rooted in justice, equity, and care?” —Nwamaka Agbo

When racial justice work is motivated by guilt or generosity, it can take a backseat during a crisis. To sustain this work, we must see how connected our hurt is.

I’m typing these words as sunlight streams through leaded glass windows to my desk. Soon I’ll tap a button and the words will stream down a digital river to you, a possible stranger. This home was built on Duwamish land, this computer on a stock-market economy. Many of our gifts are tinged with extraction.

In this complexity, we can hold both gratitude and longing. Let’s long to share a sense of plenty, without extracting from each other and from future generations. Let’s long for security of shelter, without claiming ownership of blood land. Let’s long for belonging, without othering.

It’s long been time to share without charity. To capture this moment is to see that our gifts become our property only if we choose to hoard, and hoarding leaves us longing for a more connected way to be.

Will we seize this moment to open to all that we’d forgotten to value?

WITH OUR HANDS: ACT OUT OF INSIGHT, NOT INSTINCT.

“Fast action without sufficient analysis and reflection will lead to reactions to the immediate rather than long term transformation. We need to move fast slowly.” —Marcia Lee, 2017

As we rapidly respond to the bleeding from COVID-19, let’s also remember that our system has been bleeding for centuries. What must be different this time, if we are to succeed?

When we as individuals listen deeply to the parts of ourselves that are most hurt and unheard, we can become more whole. When we as a system surrender to the communities that have carried the heaviest of our collective pain, and let it be our collective pain, we might also finally find the grief, and then the insight, to heal.

But here’s the twist: that path is neither quick nor straight. Our well-worn systemic traumas have preferred to avoid grief, to refuse letting go and instead to clamp down. Institutions would write strategy papers rather than hold space for trying out the unknown. We’d choose, once again, dirty pain over clean pain.

Will we seize this moment to grieve all that we can’t predict and control?

There’s gold in this experience. Profound hunger can make way for authentic nourishment. Profound loss can make way for authentic connection. Many of our ancestors brought trauma to this continent, trauma that we now carry, and we’re here together to heal this for a reason.

As with any trauma, we have a choice. We can try to force the outcome that fear demands. Or, we can let the trauma break our hearts open and change us in ways we can’t imagine.

The Bramble Project : Joyful and conscientious urban development

Bramble consists of Brian & Bo, two Seattle residents in the real estate industry who met as dewy-eyed grad students at the University of Washington.

We are an inevitable part of growth and change, while remaining conflicted about the negative impacts that can come with it.

Friends we love have moved into formerly low-income communities while existing residents are socioeconomically replaced. Where boring new buildings indifferently puncture existing neighborhood fabric, we want to believe that translates to affordable rents, and yet the market compels a dimmer view.

BRAVE QUESTIONS: RECALCULATING PAY EQUITY

Asking Brave Questions

Perhaps it was a gutsy move. The four of us, a multi-racial team of independent consultants for social justice organizations, working with a local food justice nonprofit on values alignment, including pay equity. We sat in a circle in our client’s empty office to negotiate and decide how we wanted to distribute the contract.

A little more context might help you understand how we found ourselves at this conversation in the first place. Our team consists of Richael, Mala, Julia and Rebecca, the four of us are close friends who socialize with each other’s partners and families, we work together on other contracts and professional endeavors, and we support each other’s other vocational work and radical dreams from writing to workshops.

We, Richael and Mala, the authors of this blog, are queer people of color–Richael is a Black, trans-nonbinary folk healer, strategist, lawyer and former organizer who supports many parts of Black, Indigeous and People of Color (BIPOC) movement community; and Mala is South-Asian queer nonprofit strategist and human resources professional who has been thinking about, creating resources, and furthering racial justice lens, within organizational development work for decades.

Our other two friends and colleagues are white and (upper) middle-class folks (who have differences across religious backgrounds, parents immigration histories, regional identifications, and skill-sets) with backgrounds in prison abolition, Central American solidarity, food justice, resource redistribution, and who lead DC-area spaces for white folks to embody their own racial justice values. We each carry deep personal, political, and vocational commitments to racial justice, and we deeply respect one another’s experience and knowledge.

With our deep experience, comes an acute awareness that, especially with the world of organizational development and diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) consulting, how much of a gap can exist between what consultants tell organizations to do, but don’t practice themselves. Namely, as our team was supporting a white-led, multi-racial organization with long-time grievances about titles, advancement, and unequal pay among staff of color, we needed to do our own work to ensure that there was pay equity within our own consultant team. Simply put, we didn’t want to be the hypocrites that we critiqued. We were working with a local food justice org to address pay equity, but we were also facing critical choices about directing money that we were earning that would allow us to feel in integrity–or not.

On one hand, we could have used a couple of standard ways to price projects. Based on our proposal, which estimated $150/hour rate for convenience, we could have calculated our estimated hours per month, assigned the hourly rate, and let our consideration end there. Honestly, this is how a lot of consultant work goes, it’s fairly simple and efficient, and doesn’t require a lot of precious energy or critical thinking.

And, on the other hand, we suspected this standard did not allow us to live our walk. Using a standard hourly rate without examining how we got here or what work we each were holding would simply mirror biased norms. At that singular moment, the convergence of our work came toan opportunity to make a bold decision. We called it out: What are the values we want reflected in this distribution?

Our conversation started, informed by our lives, research, and professional work. We named the factors that represented the values important to us:

- “Historical discrimination1.”

- “Net worth – wealth, not income2.” We ended up taking both wealth and income into account because the data shows both matter when looking at disparities in economic opportunities between black and white households.3 .

- “The number of people you support through this income4.”

- “Emotional labor5.”

- “Monthly expenses6,7.”

- And finally, “distributed and anticipated inheritance8,9,10,11.”

At the end of the conversation we were led to a much more complex set of factors than standard hourly billing could account for, and we recognized, at this stage, we needed to generate a tool to help us identify our individual rates. Our goal was to create a distribution structure that actually felt fair for all of our systemic realities which most compensation systems don’t consider (perhaps intentionally). We came up with a collective ranking and applied that to the total compensation.

To do that, we customized a pay equity process and calculator, developed by our human resources expert, Mala, which reflected each factor that we called out, along with a list of other factors based on basic needs (e.g. minimum and maximum acceptable pay rate). We each had to go through the uncommon process of collecting accurate financial data from our households, businesses, partners, and parents. Once we collected these data, and plugged them into the calculator that Mala developed, we began to use it for billing our client, which we refined with feedback and revisions.

What did we discover?

We found that our white team members significantly underestimated their own net worth and their parents’ net worth by millions, while Richael under-estimated their parents’ liabilities, which had dramatically changed in the last few years. Ultimately, we learned that despite our middle class appearances and racial justice commitments, we were the wealth gap statistics.12

We also found that alongside the statistics were: raw emotional reactions, values, tensions based on our beliefs and systemic locations, and open questions about the echo of meanings within these revelations. And yet, in our team reflection, the Black team member said this was the first time they didn’t feel resentful about their compensation within a group. We were getting closer to equity.

This real-life experiment has shaped how we think about our racial equity organization work, too. When we offered our pay equity process and calculator as an example of what was possible to our client’s staff members, we experienced a range of responses, from flowing tears of a Black program staff member (being recognized for the historical and present-day discrimination and bias she faced and had to overcome to just get a seat at the table), to polite defensiveness of a white director.

We knew immediately that we were tapping a racial equity vein not only at this organization, but within the sector and beyond. What could the life blood within our workplaces and movements feel like if we shifted the payscale and internally strengthened protections? Could social justice organizations be the source of a private reparations movement to make workplaces fairer and more effectively make market corrections?

Many people are under the impression that making public our salaries, our wealth, our access to resources is illegal. Far from it—in fact, labor regulations prohibit retaliation against workers from sharing their salaries with one another, which essentially bars policies that prohibit workers from having salary conversations. Still, many businesses have created personnel policies that prevent salary sharing, even though it’s against the law, because our modern work culture standards are set by corporate America. Income secrecy is a divisive cultural tool that fits Friedman’s free market capitalist logic, because it benefits the 1% and other mega-beneficiaries of the corporatized economy. Simply put, we don’t have to abide.

What we need to do is acknowledge that there is shame and hurt in how much racist policies have privileged some and oppressed others. Let’s not blame ourselves in the 99%. We’ve been pitted against each other long enough. But once we know the impact of these policies–including decision-makers who can make different choices, and those for whom decisions have been made and who are able to advocate and organize toward equity–let’s act.

If you have benefited from these policies, voluntarily redistribute. Voluntarily, because we are all stronger for it. When 25%13,14 of us who have been privileged voluntarily redistribute because it’s the right thing to do, the scales of justice and social pressure will turn people to do the right thing (not because of the law). The last vestige of holdouts will be moved when the law no longer hides their privilege or when their children who inherit their wealth, whose values are more justice-centered, can redistribute for them.

1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2915460/

2 http://www.lchc.org/wp-content/uploads/02_LCHC_EconJustice.pdf

3 https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/2019-economic-commentaries/ec-201903-what-is-behind-the-persistence-of-the-racial-wealth-gap.aspx

4 https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/01/the-number-of-people-in-the-average-u-s-household-is-going-up-for-the-first-time-in-over-160-years/

5 https://hbr.org/2010/09/why-is-it-that-we.html

6 https://results.org/wp-content/uploads/2019-RESULTS-US-Poverty-Racial-Wealth-Inequality-Briefing-Packet-Section-1-Final-2.pdf

7 https://s3.amazonaws.com/oxfam-us/www/static/media/files/bp-reward-work-not-wealth-220118-en.pdf

8 https://academic.oup.com/sf/article/96/4/1411/4735110

9 https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/31206/1001166-wealth-and-economic-mobility.pdf

10 https://equitablegrowth.org/race-and-the-lack-of-intergenerational-economic-mobility-in-the-united-states/

11 https://www.wilsonquarterly.com/stories/why-rich-kids-become-rich-adults-and-poor-kids-become-poor-adults/

12 We see our experiment as a form of inter-personal reparations. Learn more beyond our example. https://wellexaminedlife.com/2016/04/20/the-case-for-inter-personal-reparations/

13 Centola, Damon, et al. Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention. Science. Jun 08, 2018.

14 Centola, Damon. The 25 Percent Tipping Point for Social Change. Psychology Today. May 28, 2019.

Mala Nagarajan (she/he) is an HR consultant that works with small-to-midsize nonprofits in practicing values-based, people-centered, and movement-oriented human resources management. Mala is a systems thinker and strategist; a racial and disabilities justice advocate; and she thrives on working at the edge of innovation, developing custom client-centered tools like the Pay Scale Equity Process and Calculator(TM). As a member of the RoadMap consulting network, she has coordinated their HR/RJ working group, supported their My Healthy Organization and Our Healthy Alliance online assessments tools, and works with multiracial teams to untangle thorny equity issues embedded in organizational culture, structures, and systems.

Richael Faithful (they/them) is a multidisciplinary folk healer, facilitator, strategist, creative and lawyer. Part of their work supports groups that are developing healing culture and practices with analyses of power and systems. Learn more about Richael at: www.richaelfaithful.com

featured image by Micheile Henderson

DECENTRALIZED NETWORKS AND THE BLACK RADICAL TRADITION – PART 1

FROM COLLECTIVE ORGANIZING TO BUILDING BLACK FUTURES

Every second Thursday of the month, Network Weavers Yasmin Yonis, Kiara Nagel and Marie DeMange host a Community of Practice conversation on Zoom. The skill-building space is available for network weavers who want to create connections and to explore questions central to their roles as facilitators, consultants and movement builders.

In March, the Community of Practice session was dedicated to unearthing what the Black Radical Tradition can teach us about how communities are self-organizing under crisis. Digital Strategist, social entrepreneur, and faith-based organizer Jayme Wooten and former organizer and founding member of Black Lives Matter Global Kei Williams, led the session through a riveting presentation that highlighted how network weaving in movement building creates strong, sustainable, and participatory avenues of community engagement.

In this first installation, I’ll be exploring some of the ideas that resonated with me from Jamye Wooten’s presentation. Join us next week for a second blog post on Kei William’s reflections on the difference between a riot and a rebellion, identifying key moments in a movement and power mapping.

What Moves You to Organize?

One of my key takeaways from the conversation was a question Jamye offered up to the group early on: “How do we move beyond react-ivism to a framework that is more wholesome and holistic?” When I think of activism, I think of forward movement, critical response to urgent community needs. What Jamey’s question opened up for me was an opportunity re-examine the impulse to act. Activism often comes out of a reaction to a perceived injustice. That reaction while visceral and binding, while it galvanizes communities towards action also depends on the viscerality of a trauma response for endurance.

Some good questions to ask in community:

Where in our organizing have we mistaken “react-ivism” for “activism”?

What can we offer as a community in its stead?

Is there room in our reaction to great harm for quietude and spaciousness so that we can recover and organize alongside our comrades?

What Kind of Network Makes a Movement?

A robust and inter-related one.

Another great offering from Jamye was an invitation to look closer at the parallels between movement building and Network Weaving. While people might remember Martin Luther King or Phillip Randolph as leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, what made the movement successful were core members like Ella Baker who helped local leaders in southern communities activate talented and capable young folks to self-organize. [1]

At the core of every network is a relationship, Jamye offers, and crucial to that relationship is trust. We often overlook the importance of relationship and trust building in the health and longevity of networks in an effort to make sure more work gets done, and yet, a sustained, years-long trust-building effort is the only way Baker’s could have galvanized as large and loose a coalition throughout the South as she did.

To that end, it’s important to know what each network needs to be able to organize resources to ensure its success. For example, an Action Network is just a collection or clustering of people who are interested in executing similar tasks: fundraising for an event or creating a mutual aid pod. What an Action Network needs to thrive might be different from a Support Network which is likely the comms and evaluations core of any successful self-organizing pod. That being said, a good Action Network is nothing without a robust Support Network, a collection of folks willing to build out systems and stay on top of resources. And a robust Support Network relies on the trust building, collaboration and thoughtful strategies that come out of relationships in intentional networks. Networks are not so much separate pods with a shared core as they are a spider

Are you using a Centralized vs. Decentralized Models?

According to Jamye’s research, successful Networks are not so much spidery pods with a powerful core as they are a starfish with deeply interconnected and communicative limbs. Thinking of the limbs of the Starfish as replicable and healthy parts of a network allow us to see the importance of each part: Circles, The Catalyst, Ideology, Pre-existing Network, The Champion. A healthy network needs all of these parts to be aligned in vision, communication, interlocking values and principles so that they can adequately organize for power.

A great example of such a model in practice are the hashtag based campaigns such as #BMoreUnited in response to the spotlight on Baltimore in the aftermath of Freddie Grey’s shooting at the hands of Baltimore Police. What emerged was a coalition of citizens who operated as a network without any real leadership structure to demand justice and accountability for police shootings in their community. They were able to do so by prioritizing participatory democracy and building out a skills bank to utilize the human and financial resources that came pouring in after the media spotlight.

From Collective Organizing to Building Black Futures

The last and arguably coolest lessons from the session is that it’s possible to use digital spaces to ethically organize on behalf of communities in ways that are participatory and rigorously innovative. Take CLLCTIVLY “a place-based social change ecosystem using an asset-based framework to focus on racial equity, narrative change, and social connectedness.” The most remarkable aspects of CLLCTIVLY: its asset map/directory which aims to amplify and connect community members with multimedia projects, a strategic partnership/marketplace, a social impact institute, and a rotating Black Futures Micro-Grant . Using the seven principles of Kwanza, CLLCTIVELY aims to put old money in service of new values. COLLECTIVELY- create ecosystem to foster collaboration.

Resources:

- Old Money, New Money 2019: A Community of Practice in Three Parts

- Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision by Barbara Ransby

[1]https://time.com/4633460/mlk-day-ella-baker/

Watch the video of the session by downloading the free resource HERE.

About the author:

Sadia Hassan is a facilitator and network weaver who has enjoyed helping organizations use a human-centered design approach to think through inclusive, equitable, and participatory processes for capacity building.

She is especially adept at facilitating conversations around race, power, and sexual violence using storytelling practice as a means of community engagement and strategy building.

She is an MFA candidate in Poetry at the University of Mississippi and has a Bachelor’s degree in African/African-American Studies from Dartmouth College.

DEEPER THAN HAIR DISCRIMINATION: A MOVEMENT TO ADDRESS AND DISMANTLE SYSTEMIC RACISM

When I graduated from Columbia University, I was informed in a professional development workshop at a national conference that my hair should not distract from my excellent credentials. I did not understand how hair that grew naturally out of my scalp could be labelled as a source of barriers. The styles that were mentioned as socially acceptable for professional upward mobility were straight hairstyles that did not reflect the texture of my natural hair.

As co-founder of the CROWN Campaign, a movement founded to end discrimination and injustice of all forms including hair discrimination. I have had lived experiences of hair discrimination which fueled my passion to address systems transformation through a lens that is informed by my interdisciplinary background. CROWN campaign is an interdisciplinary team and growing village of grassroots advocates in academia, business, policy, journalism, research, health, law, the arts, and community who have lived experiences of hair discrimination, know of those impacted by hair discrimination, and have been engaging voices from around the country and globe on experiences with hair discrimination. The CROWN campaign is a labor of love.

1. A few things to know about the CROWN Campaign

The CROWN Campaign was founded to end discrimination and injustice including hair discrimination locally and globally and we do this using a “it takes a village approach”. The CROWN campaign village has shared expertise in research, law, creative arts, journalism, business, virtual and in-person activism and many other areas.

2. My Hair, My Crown, My Freedom

I have recently written and directed a short animation film, entitled “My Hair, My Crown, My Freedom” and brief discussion guide to engage local and global populations on what a diverse, equitable and inclusive world can look like.

The short animation film can be found HERE

3. Journey of the CROWN Campaign

The journey for the CROWN campaign began in February 2019, when the New York City mandate against hair discrimination was announced. I was sitting on the couch as I read the news about the hair ban. Reading the New York City hair ban validated and emboldened my voice and experiences in terms of the discrimination that I faced and I reached out to individuals in my network through a mass chain of emails about tackling this issue from an interdisciplinary lens including reaching out to Shemekka Ebony who would become a co-founder in this movement. It started with many emails. In the initial stages, there were some who said “it is just hair” and the black community has more pressing issues to address in terms of systemic racism.

Those of us who have had lived experiences knew that it is deeper than just hair in terms of impacting educational attainment, employment opportunities, upward mobility, health and well-being. This further emoboldened me to share my experiences and reach out in my networks to get an interdisciplinary team together to provide evidence on the harmful impacts of hair discrimination from a big picture lens as being much deeper than hair.

The individuals I initially engaged then referred other individuals who came to form the core crown campaign team and subsequently the growing village who have contributed their expertise. For example, Shemekka Ebony, co-founder, has been instrumental in developing the network of activist through social media advocacy. Dr. Manka Nkimbeng joined the team bringing in the research lens of the health impacts of discrimination from her dissertation research. Both Shemekka Ebony and I mentored Dr. Manka Nkimbeng as part of the Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Research Program where she expressed an interest in crown campaign’s efforts and wanted to focus her enhanced learning project on the health impacts of hair discrimination. Crystal M Richardson and JB Afoh Manin have focused on the legal and policy angles with JB’s focus being on men and hair discrimination.

4. It’s Deeper than Hair – Black Hair History and perpetuation of systemic racism today

The CROWN Campaign will be launching a global series called deeper than hair to further contextualize the health, economic, social justice, and well being impacts of discrimination. In the black community, hair and hairstyles have strong historical, political, cultural, social, and familial significance in terms of identity. Such hairstyles include afros, braids, bantu knots, locs, African thread styles, twists, fades, and leaving hair in various forms of its natural state.

Unfortunately, individuals have been discriminated against on the basis of the expression of this cultural identity and practice of natural hair/hairstyles. This has resulted in a number of inequities in activities of daily living such as lack of employment opportunities, discrimination in the workplace, discrimination in school settings, job loss, microaggressions and much more. In a number of case studies, individuals have been told to conform to the dominant culture for assimilation and upward mobility further promoting racist stereotypes. There is strong research evidence on the adverse effects of different forms of discrimination on health, social determinants of health, and equity.

Understanding the historical context of black hair helps us to understand how systemic racism has been propagated in policies. Dr. Patricia O’Brien Richardson, one of the CROWN Campaign collaborators in academia provides an in-depth historical context based on her research as follows: “Black people have a rich history with hair beginning in Africa. In the earliest African civilizations, hair was considered a cultural marker and used to indicate age, marital status, wealth, rank, and tribal affiliation. In American society, hair has historically been used as a tool of systemic violence against black men and women who have been socially penalized and stigmatized for their hair. During colonial period and later in the Jim Crow era came to be described as wild, unkempt, messy, sweaty, knotty, dirty, and nappy. Wild, messy hair was often equated with wild behavior, signifying insanity.”

We see similar words, “unkempt” “wild” “messy” “nappy” “unprofessional” perpetuating structuralized and systemic racism in workplace and school grooming policies today.

5. Impact of the CROWN Campaign

Since the vision and inception of CROWN Campaign in February 2019, CROWN Campaign has provided advocacy and presentations around the country, and has a growing list of partners in advocacy, including partnering with Dr. Patricia O’Brien Richardson who envisioned the first ever historic inaugural CROWN Conference in New Jersey. An attendee at this conference, Karla Arroyo, a journalism student, has become our first inaugural CROWN Campaign fellow. She will be completing her capstone as part of the fellowship with a focus on community organizing and uplifting the stories and voices of those impacted. I, along with the CROWN campaign team and crown campaign village, will be mentoring her from an interdisciplinary framework of co-design.

Due to a request from policy makers for research on hair discrimination, CROWN campaign has created a readily accessible starter library in the resource section for evidenced based research on the impacts of hair discrimination because we recognize that it is deeper than hair. We all have lived experiences and have interacted with individuals and communities who have been severely impacted from hair discrimination in terms physically, socially, mentally.

The CROWN campaign team and village contributes expertise in the creative arts including photography, film, scholarly research, journalism, written and spoken word, in person advocacy and educational outreach, as well as social media advocacy. CROWN campaign has developed tools and resources and also curated tools and resources from the growing village that can be found here. In the village, we want everyone to feel empowered to lift their voice and expertise in various forms to dismantle racism. We have seen this manifest beautifully in the village through research, advocacy, poetry, film photography, legal, policy and many other areas. The tools and resources can be found HERE.

6. CROWN Campaign Advocacy Case

CROWN Campaign has been in advocacy for cases of discrimination including most recently two young boys who were deprived of an education within the Tatum Independent School District for natural hair. CROWN Campaign provided expert witness testimony and an advocacy letter.

It truly takes a village to dismantle racism and CROWN campaign with the help of the growing village is taking an interdisciplinary approach to tackle and dismantle racism using a multi-prong approach.

The CROWN Campaign is a team of volunteer advocates that are self-funding this important work across the United States and beyond. We cannot do it alone. We need your help!We are a growing Interdisciplinary collective of community members, professionals, and experts with lived experience that are championing the advocacy and education of the impacts of hair discrimination to natural hair citizens. We need support funding the travels, events, expenses, and labors of love from our team. Donations from those that believe in this work and can identify with the need for change, please donate and share. http://www.crowncampaign.com/donate.html

Learn more about the CROWN Campaign at www.crowncampaign.com

FB IG & Twitter @crowncampaign

Dr. Bernice B. Rumala is Co-Founder for the CROWN Campaign , an effort aimed at ending discrimination and injustice locally and globally, including hair discrimination. With more than 15 years of experience, Dr. Rumala earned a PhD and three masters degrees from Columbia University and served as a Fogarty-Fulbright and Harvard Fellow. She has contributed her interdisciplinary expertise as a change agent in the public, private, academic and international sectors. As a former senior consultant for the United Nations, her areas of interest and expertise include equity, health equity, social justice, diversity, inclusion, discrimination, interdisciplinary-programming, advocacy, community engagement, and systems transformation.

Dr. Rumala has lived experience of the ongoing challenges of severe inequities and the detrimental impacts to individuals and communities, specifically vulnerable communities and communities of color. This is unacceptable to her and should not be the norm. Dr. Rumala also considers herself a global citizen based on international experiences in more than thirty countries. She has had global experiences in stable regions as well as regions impacted by war, conflict, and instability, including Iraq where she worked for the United Nations. She continues to contribute her expertise as a global and local leader, consultant, and, is the Founding CEO of the Change Agent Firm.

A PATH OF LEARNING, RECOGNIZING AND HONOURING TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION

It was the release of the Truth & Reconciliation Commission reports that nudged our organization to read, reflect and better understand how we could both as an organization and network learn our country’s history and advance truth and reconciliation. We had been intentional about recruiting someone to serve on our board of directors from the Indigenous community as we came to realize that our board’s diversity program didn’t take the Indigenous community, the first peoples of this land, into account. We had started to incorporate a land acknowledgement at the outset of our workshops and events; however, we stumbled and didn’t get things quite right and required some education and guidance.

As an organization we are on a journey to listen deeply, engage and be in true dialogue. Because we are uneasy as a sector about misstepping there can be a chill in engaging with truth and reconciliation. We need to create courageous spaces as there is an urgency to this issue and ask ourselves what are we doing each day towards reconciliation. We need to learn from a place of understanding and not place ourselves as hero or saviour. There is an immense amount of work as settlers, immigrants and as a community as a whole that we need to do related to truth and reconciliation and we cannot expect Indigenous people to continually provide emotional labour by educating us, or holding us and our healing.

LEARNING

It starts with learning and understanding the full history, stories and our shared responsibility as settlers. We need to acknowledge the harm and understand the intergenerational trauma and impact of residential schools, the Sixties Scoop and other atrocities towards Indigenous peoples by both settlers and the government.

Many of Pillar’s staff have participated in the Indigneous Cultural Safety program from Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre, an interactive and facilitated online training program that addresses the need for increased Indigenous cultural safety within the system by bringing to light the service provider bias and the legacies of colonization that continue to negatively affect service accessibility and health outcomes for Indigenous people.

Further, our staff team have participated in programs and learning opportunities that have included an Indigenous learning arc including Banff Centre’s Social Innovation Residency and Foundations of Purpose Program; Social Capital Partners (SOCAP18); Ontario Nonprofit Network’s Nonprofit Driven Conference; Imagine Canada Sector Champion Roundtable; Resilient Cities Conference; London Environmental Network’s River Talk Conference and EconoUS.

For our network, board and staff we participated in and held sessions of the KAIROS Blanket Exercise. The exercise is an interactive learning experience that teaches the Indigenous rights history, increases our awareness of Canadian history as it pertains to Indigenous peoples’, promotes empathy, and inspires action towards reconciliation. We first hosted it as a public session at Innovation Works, a shared space for social innovation, and it sold out. Since it evoked much emotion and reflection, we decided to continue running the sessions. The second time we hosted it at an Indigenous based partner Atlohsa Family Healing Services, and this was an example of how connecting and going to an Indigenous organization was a more impactful experience.

Furthermore, we have been hosting decolonization workshops, Indigenous sharing circles and a local Indigenous learning series for the nonprofit sector so that other community members can explore Canada’s shared history, stories and work towards solutions on decolonization to build stronger, more positive relations with Indigenous people.

RECOGNIZING AND HONOURING

Nokee Kwe’s +Positive Voice program supporting urban Indigenous women in creating positive narratives and community connections was the recipient of the 2017 Community Innovation Award for the Pillar Community Innovation Awards. Former Program Coordinator, Summer Thorp remarked, “The wonderful thing about being nominated and receiving the award is the sense of ownership that the Indigenous women in our program feel; this truly is their award. Having their bravery, resilience, and accomplishments recognized by the community on such a large scale is a validating experience that they proudly share when talking about their achievements.”

Like many organizations, Pillar adopted the practice of sharing a land acknowledgement before workshops and events. By making a land acknowledgement you are taking part in an act of reconciliation, honouring the land and Indigenous presence. We started with a fairly brief version and stumbled over the pronunciation. We had an Indigenous colleague come and provide some training in the pronunciation.

ALL CANADIANS MUST NOW DEMONSTRATE THE SAME LEVEL OF COURAGE AND DETERMINATION, AS WE COMMIT TO AN ONGOING PROCESS OF RECONCILIATION. BY ESTABLISHING A NEW AND RESPECTFUL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ABORIGINAL AND NON-ABORIGINAL CANADIANS, WE WILL RESTORE WHAT MUST BE RESTORED, REPAIR WHAT MUST BE REPAIRED, AND RETURN WHAT MUST BE RETURNED.The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Over time we were hearing that land acknowledgments were feeling like a check box and they should be customized and aligned with the intent of the event and we started to personalize each one to the person who was delivering it and the event we were hosting. Still this did not feel right and we met with various Indigeneous colleagues to seek their guidance. Today, we have an elder open with a welcoming or prayer and then we have a settler do the land acknowledgement and share their role in truth and reconciliation. A welcome and land acknowledgement is only a start and organizations need to understand there is much more we can action together.

Pillar encourages and supports those who wish to participate in smudging ceremonies. Smudging is the burning of sacred medicines and is meant to purify, protect, ground and harmonize people and spiritual spaces and is a common practice among Indigenous people. We have had concerns related to allergies and location in our space and therefore we created a smudging policy that states that it is a welcome practice at Innovation Works and it includes notifying our co-tenants of timing and location. Pillar recognizes the spiritual and cultural importance of Indigenous practices, and is committed to creating an inclusive environment for its co-tenants and the wider community.

PARTNERING AND SUPPORTING

Through our social enterprise and nonprofit supports we have worked alongside Yotuni that provides mentoring, guidance, cultural education teachings, workshops and healing circles to provide the tools and life skills for Indigenous children and youth to live positive and healthier lives. Further, Kuwahs^nahawi is a social enterprise that provides consulting, educating and facilitating using Indigenous practices, specializing in teaching truth of Indigenous People and history, and ways we can work together towards healing and reconciliation that Pillar has engaged for several sharing circles and workshops. We have also supported Atlohsa Gifts that sells authentic products from Indigenous artisans throughout Canada to help fund the services of Atlohsa Family Healing Services. We have offered incubation, business planning and market connections. Further, Pillar as part of its social procurement sources the services of these two social enterprises for consulting, workshops and gifts for our speakers and staff.

When developing new partnerships, it is essential to engage Indigenous-led organizations as partners in the development of the project. When we were seeking interest in having Indigenous leaders on nonprofit boards we were reminded that we had made an assumption that they would want to sit on boards. A group of Indigenous leaders have been coming together to explore about what leadership means to them and how that dovetails with nonprofit governance. It had surfaced questions about how nonprofit boards are colonized and whether they are inclusive. Most recently, we have built a partnership at the outset of a new program with Centre for Social Innovation and Nordik Institute for a new provincial program, Women of Ontario Social Enterprise Network funded by the Government of Canada through the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario. This new program is focused on supporting women social entrepreneurs and is based on inclusive design and Indigenous approaches to venture creation.

Through learning, recognizing and honouring our history, Indigenous people and their traditions we are witness to the resilience, courage and determination they have and continue to demonstrate daily.

IDEAS FOR INCORPORATING WORK WITH THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY INTO YOUR ORGANIZATION

- Learn and acknowledge history – Learn the history and acknowledge the harm and atrocities in our shared Canadian history including reading the Truth & Reconciliation reports

- Recognize the urgency – There is an urgency to Truth & Reconciliation because hard and atrocities are still happening today

- Make incremental progress – Ask yourself how you can make progress towards reconciliation each day in your organization

- Follow not lead – Go to Indigenous related organizations, events and training rather than asking Indigenous people to come to you on boards, committees and events

- Recognize power dynamics – Acknowledge power in all interactions and be prepared to give up power

- Build relationships and trust – This is a critical step before jumping to requesting a partnership

- Consider how to redistribute wealth – Look at strategies such as a granting and investments and have the Indigenous community as a priority and focus

- Have the right partners – Pause and ask who is missing in the room and be intentional

- Create a social procurement policy – Consider purchasing from Indigenous-based social enterprises and business

- Go beyond land acknowledgements – If doing them have a welcome from an Indigenous elder and land acknowledgement by a settler to make it meaningful

- Explore Indigenous cultural traditions – Learn about the 7 Sacred Teachings and other Indigenous cultural traditions including the medicine wheel and smudging from a place of learning without appropriating

- Create courageous, safe and open spaces – Make sure your organization and community is inclusive of Indigenous people and all people

Originally published at The Network Approach by Pillar Nonprofit Network

“The Network Approach by Pillar Nonprofit Network shares our evolution as a place-based and impact-focused network as well as our promising practices using the network building principles that have guided us since our inception. Each piece of content on this site showcases a part of our journey towards becoming a thriving network organization, even our logo helps to tell the story as radiant nodes shine outward to represent an expanding network.”