Into the Matrix and Beyond: The Value of Network Values and Values-Focused Processes

A couple of years after the Food Solutions New England Network officially published the New England Food Vision, and just after the network formally committed to working for racial equity in the food system, it formally adopted a set of four core values. On the FSNE website, a preamble reads: “We collectively believe that the food system we are trying to create must include substantial progress in all these areas, alongside increasing the consumption of regionally produced foods and strengthening our regional food economy and culture.” The four values are:

Democratic Empowerment:

We celebrate and value the political power of the people. A just food system depends on the active participation of all people in New England.

Racial Equity and Dignity for All:

We believe that racism must be undone in order to achieve an equitable food system. Fairness, inclusiveness, and solidarity must guide our food future.

Sustainability:

We know that our food system is interconnected with the health of our environment, our democracy, our economy, and our culture. Sustainability commits us to ensure well-being for people and the landscapes and communities in which we are all embedded and rely upon for the future of life on our planet.

Trust:

We consider trust to be the lifeblood of collaboration and collaboration as the key to our long-term success. We are committed to building connections and trust across diverse people, organizations, networks, and communities to support a thriving food system that works for everyone.

In the last few years, these values have generated a lot of good discussion, both internal to the network and with others, and we are discovering that this really is the point and advantage of having values in the first place. They can certainly serve as a guide for certain decisions, and in some (many?) instances things may not be entirely clear, at least at first. What does racial equity actually look like? Is it possible for a white-led, or white dominant, institution to embody racial equity? Can hierarchical organizations be democratic? Are there thresholds of trust such that people are willing to not be a part of certain decisions in the name of moving things forward when needed?

Recently, FSNE received an email from a Network Leadership Institute alum who now works as a commodity buyer for a wholesale produce distributor in one of the New England states. They reached out to inquire who else in the network might be thinking about high tech greenhouse vegetable production in the region. Specifically their interest was talking about projects that use optics of being “community based,” but are financed by big multinational corporations. “What would a “just transition” framework look like in the context of indoor agriculture,” they wondered, especially in light of undisclosed tax deals happening as the industry rapidly grows.

As it turns out, a public radio editor recently reached out to FSNE Communications Director, Lisa Fernandes, about pretty much the same thing, also referencing other similar projects taking root in different parts of the region. What does FSNE think of these? Part of her response was that there are some good questions that not only the New England Food Vision (currently being updated), but also the Values, can raise to evaluate the potential role of some of these more tech-heavy food system projects and enterprises as the region strives to be more self sufficient in its food production. And this conversation is certainly growing.

These exchanges in our region have had me thinking about work colleagues and I have been doing with food justice advocates in Mississippi. A central part of this also lifts up values as being key to establishing “right relationships” between actors in the food system, and also between advocates and partners (including funders) from outside of the state. I have learned much from Noel Didla (from the Center for Ideas, Equity, and Transformative Change) and her colleagues about the importance of establishing what they call “cultural contracts,” which create a foundation of values-based agreements as a way of exploring possibilities for authentic collaboration. The signing of any contract is just a part of a process of ongoing dialogue and trust building. For more on these contracts and culture building, see the recording of a conversation Karen Spiller and I had with Noel and other Mississippi food system advocates during the FSNE Winter Series earlier this year in a session called “The Power of the Network.”

“Daring leaders who live into their values are never silent about hard things.”

Brene Brown

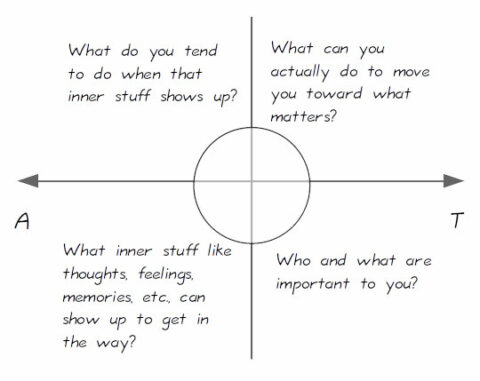

In a different series of workshops with those same Mississippi-based advocates, we introduced a values-focused tool from the PROSOCIAL community. PROSOCIAL is rooted in extensive field research (including the commons-focused work of Nobel Prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom) and evolutionary and contextual behavioral science. PROSOCIAL offers tools and processes to support groups in cultivating collaborative skillfulness and the critical capacity of psychological flexibility, including the application of Acceptance and Commitment Training/Therapy (ACT) techniques.

The ACT Matrix (see below) is something that individuals and groups can use to name what matters most to them (their core values), along with aligned behaviors (what are examples of living out these values?), as a way of laying a foundation for clarity, transparency, agreement, support and accountability. The Matrix also helps people to name and work with resistance found in challenging thoughts and emotions that might move them away from their shared values. The upper left quadrant is a place to explore what behaviors might be showing up that move people away from their stated values. In essence, this helps to both name and normalize resistance and when used with other ACT practices (defusion, acceptance, presence, self-awareness), can encourage more sustainable, fulfilling (over the long-term), and mutually supportive choices.

An additional values-based tool we have lifted up both in New England and in our work in Mississippi is Whole Measures. Whole Measures is a participatory process/planning and measurement framework from the Center for Whole Communities). There is both a generic version of this framework, as well as one specifically focused on community food systems (more information available here). As CWC points out, “How the tool or rubric framework is used, how the community engagement is facilitated, who is represented in the design matters.” Whole Measures is about content, yes, and it is meant to be used for ongoing deep dialogue, especially amidst complexity, diversity and uncertainty, and when faced with the challenge of tracking what matters most that can also be difficult to measure.

When it comes down to it, these times seem be asking us what kind of people we really are and strive to be. As the old saying goes, “If you don’t know what you stand for, you’ll fall for anything.” And so the work of values identification and actualization is of paramount importance. I’ll leave it to the poet William Stafford to appropriately close this post with his poem, “A Ritual to Read to Each Other” (something we often share with social change networks as we launch, especially the first and last stanzas):

If you don’t know the kind of person I am

and I don’t know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the world

and following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,

a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break

sending with shouts the horrible errors of childhood

storming out to play through the broken dike.

And as elephants parade holding each elephant’s tail,

but if one wanders the circus won’t find the park,

I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty

to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.

And so I appeal to a voice, to something shadowy,

a remote important region in all who talk:

though we could fool each other, we should consider—

lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark.

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate at the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC). Much of his work entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food, education, public health, and economic systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

featured image found here

Value and Impact of the Purpose Built Community of Practice

Knowledge Communities, in collaboration with Purpose Built Communities, have released a white paper (that you can download below) telling the story of Purpose Built’s successful and compelling journey to adopt and implement a Community of Practice (CoP) strategy to support neighborhood revitalization and racial equity. Specifically, the paper describes the Purpose Built CoP startup process, the status of the Purpose Built CoP as of early 2021 and success factors to date. Finally, the paper contains an appendix of tips for practitioners who support and manage CoPs and networks.

- Read about how the Purpose Built Community of Practice (PB CoP) successfully supported a network of change makers across the country during COVID and continues to support them on an ongoing basis today.

- Learn some practical strategies you might want to adopt as you build a community of practice.

- Understand why the PB CoP exemplifies best practices from which many can learn.

Communities of Practice bring together professionals who share a common set of challenges (e.g., Purpose Built Network leaders focused on place-based community development) on an ongoing basis to collaboratively solve problems and learn from each other.

Article Summary

Purpose Built Communities brings together Network Members — leaders and staff of organizations working to improve equity and opportunity in neighborhoods across the country — in a networked Community of Practice (CoP) structure. Knowledge sharing and collaboration helps local leaders in the Network tackle the complex challenge of intergenerational poverty to achieve racial equity, improved health outcomes and upward mobility for residents.

In 2019, with the generous support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Purpose Built Communities began moving from a hub-and-spokes structure (with Purpose Built serving as the hub), to a Community of Practice, also known as a networked model.

The Purpose Built Community of Practice stimulates problem recognition, and the creation, exchange and application of innovations to serve place-based neighborhood revitalization that moves people out of poverty.

The CoP’s structure and interactions help Network Members:

- Build stronger relationships with supportive peers

- Accelerate knowledge sharing

- Respond rapidly and flexibly to changes in circumstances

- Shorten learning curves to gain skills and expertise fundamental to Network Member excellence

- Successfully implement the Purpose Built Communities model

- Make informed decisions that create stronger outcomes

For more information, read the full white paper, “Value and Impact of the Purpose Built Community of Practice: 2019-2021″

Access the paper by downloading the resource at Network Weaver HERE or at Knowledge Communities's website HERE.

The mission of Knowledge Communities is to create environments that optimize:

- Trust building

- Collaboration

- Synergy

- Knowledge Sharing

- Generative Behaviors

- Harness the productive dimensions of power and competition in the service of improving lives and bettering the world we live in.

Originally published at Knowledge Communities

Centering equity within networks

Collective Mind hosts regular Community Conversations with our global learning community. These sessions create space for network professionals to connect, share experiences, and cultivate solutions to common problems experienced by networks.

Our April 21, 2021, the Collective Mind Learning Community welcomed Ericka Stallings, Executive Director of Leadership Learning Community, to share her experiences, learnings, and challenges of working with networks to center and operationalize equity within their network practice. Leadership Learning Community is a national learning network that works to transform the way leadership development is understood, practiced, and evaluated in order to advance an equitable and just society, promoting leadership that is equity-based, networked, and collective. The session generated a conversation amongst participants around shared challenges, successes, and experiences based on their efforts to integrate equity within their networks.

Highlights from the conversation

The nature of network practice embodies the principle that a network’s strength is in its diversity. Finding equitable ways to harness that diversity is something most networks strive for. However, equity, both in definition and in practice, is as complex as networks themselves. As highlighted by our co-host’s presentation and through the community conversation, how networks choose to define equity, and how it is moved from concept, theory, and values to embodied and lived actions within a network can be dynamic, difficult, uncomfortable, rewarding, and necessary.

The conversation began with a definitionof equity, and an acknowledgment that it was only one of many ways to define equity. Part of that definition — “the guarantee of fair treatment, access, opportunity, and advancement while at the same time striving to identify and eliminate barriers that have prevented the full participation of some groups” — can, in part, be advanced through a network’s commitment to transparency and communication. However, as highlighted by our co-host’s experience, it should be done in a way that prioritizes people’s understanding and bi-directional communication, rather than overwhelming them with data, information, and updates. A perceived lack of transparency and communication by the network can damage trust and reduce participation, both of which are core to building an equity-centered network.

Another learning was the importance of centering and naming equity as a network value and goal and establishing a culture that centers equity. A network’s culture establishes values, norms, attitudes, and practices of the individuals’ and groups’ behaviors that influence their interactions. It maintains the network’s shared purpose and fosters ongoing collaboration, enabling these constructive dynamics and spaces and ensuring they are embodied in all network undertakings. A network culture centered on equity means shifting the network’s norms and dynamics to support and enable equity across its activities and then also asking if the outcomes achieved are in line with the values that were articulated.

Taking steps to move equity from something that is spoken to something that is operationalized can be uncomfortable, messy, and disruptive. However, much like the overall work of a network manager, it’s important to work with the discomfort, rather than against it. The process of operationalizing equity requires investing in relationships, deep listening, innovation, and experimentation. For example, participants described ways in which they had experimented with how to deepen network engagement such as holding space for formal and informal listening sessions, conducting surveys, creating affinity groups, incorporating consent-based decision-making, and integrating trust-based models. Core to this all is for the network to be willing to go through the process of experimentation and learning. In some cases, efforts may be met with failure, and in others, success. However, the ability of a network to create the space and invest in the efforts will ultimately foster trust in its network relationships, which is critical to its productivity and impact. Trust increases participation and collaboration, and it is only through collaboration that the network is able to achieve something greater than the sum of the parts.

How to authentically and meaningfully operationalize equity within a network parallels many aspects of what it means to be an effective network manager. It may look different for each network depending on its goals, breadth of diversity and composition, its mission, and many other factors. Networks, and a network’s culture, are dynamic, shifting constantly in the face of external and internal changes. Just as network managers and leaders must often accustom themselves to messiness, working with it instead of against it, operationalizing equity means disrupting and deconstructing systems and being open to conflict and discomfort. Having clear values and goals at the outset, and constantly questioning, learning, and assessing can help determine if and how a network’s efforts are progressing and if they are creating disruptive opportunities to increase equity. As mentioned by our co-host, if you’re feeling too comfortable, it may mean something has been missed.

Miss the session? View the recording here.

Thanks again to our co-host, Ericka Stallings from Leadership Learning Community!

Get involved

Have your own experiences with efforts to center equity in network practice? Tell us about it in the comments below.

Join us for the next Community Conversation!

Or email Seema at seema@collectivemindglobal.org to co-host an upcoming session with us. Learn more about co-hosting here.

Collective Mind seeks to build the efficiency, effectiveness, and impact of networks and the people who work for and with them. We believe that the way to solve the world’s most complex problems is through collective action – and that networks, in the ways that they organize people and organizations around a shared purpose, are the fit-for-purpose organizational model to harness resources, views, strengths, and assets to achieve that shared purpose.

Originally published HERE

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Collaborative Funding for a Just Transition

Several months ago I was interviewed by Leslie Meehan and Ben Roberts of Now What?! The topic was Collaborative Funding for a Just Transition and we explored innovative strategies to generate needed financial resources for networks. Some of the topics we discussed were:

- New ways that networks can think about money that help them move out of individualistic approaches to fundraising to network approaches to money and resource generation.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- How networks can lessen the need for external funding by encouraging network participants to meet each other's needs. For example to mentor each other more rather than relying on paid consultants and to work more collaboratively (for example, aggregating orders to get much lower costs for supplies).[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- How networks can set up income generating activities to support their work.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- How to make grants collaborative so that many network partners can access new resource flows.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- How putting grant funds into Innovation Funds (where decisions about the funds are made participatively) creates more democratic structures to control the flow of funding.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Building massive social media and communications networks and using those for fundraising.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- What innovations have you been part of that explore network approaches to resource generation? How might you apply some of the ideas presented in this video?

featured image found HERE

June Holley has been weaving networks, helping others weave networks and writing about networks for over 40 years. She is currently increasing her capacity to capture learning and innovations from the field and sharing what she discovers through blog posts, occasional virtual sessions and a forthcoming book.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

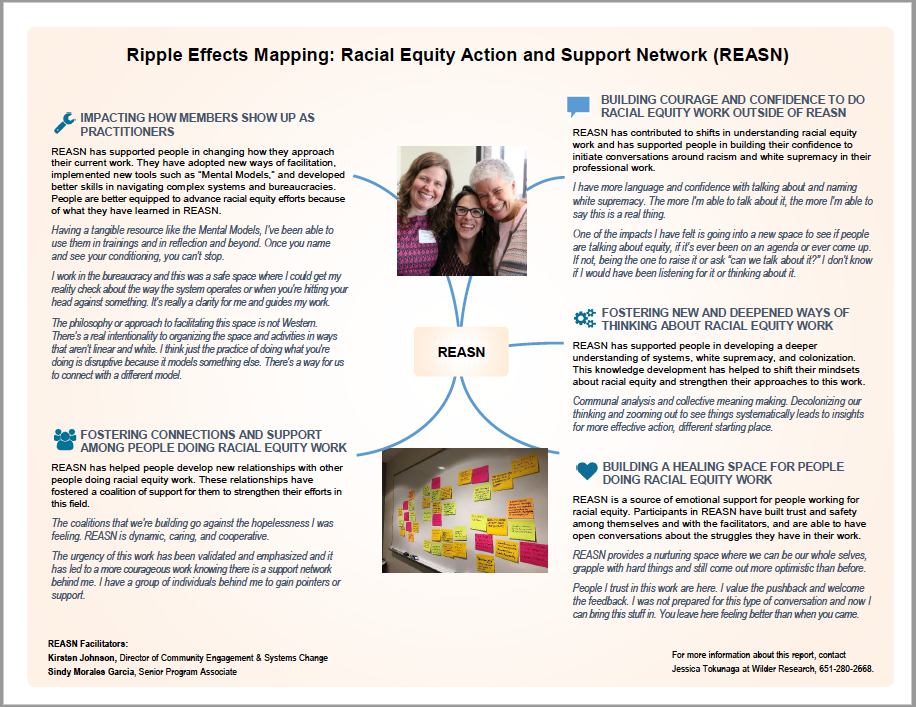

A Network of Support for Racial Equity Leaders

Working to advance racial equity in systems and organizations is challenging and often isolating work. REASN - the Racial Equity Action Support Network - is a network in Minneapolis St. Paul that brings together Minnesota’s racial equity leaders and practitioners, the people whose job it is to design, facilitate and lead the efforts that enable community, nonprofit, and government organizations to advance equity. At REASN, these equity change agents find a space that provides:

- Support for doing the challenging, and often isolating work of creating racial equity

- Action strategies that are more powerful and effective as they are rooted in shared analysis and reflection

While there are many spaces that provide education and skill-building for those who are committed to racial equity, REASN is unique in offering a space for those who are responsible for leading those education, skill-building and systems change efforts. It provides a space of respite, learning and growth for those who are often in the position of hosting and supporting others.

In 2020, REASN could see transition on the horizon as funding and structural changes were underway in the organization that had served as its fiscal host. The network decided it was the opportune moment to invest in an evaluation that would document REASN’s impact over its 6 year history. Network members wanted to be able to tell the story of REASN to those who might support its sustainability. We chose ripple effect mapping as the evaluation tool to support us.

Ripple Effect Mapping

REASN hired a team of facilitators from Wilder Research to lead us through the Ripple Effect Mapping process. Network members worked alongside this team to create the purpose and questions that would guide the process.

Here’s how our evaluation partners at Wilder Research describe the process: Ripple Effect Mapping (REM) is an evaluation tool used to better understand the intended and unintended impacts of a project. It is particularly helpful when evaluating complex initiatives that both influence, and are impacted by, the community. REM is a facilitated discussion with staff and local stakeholders that creates a visual “mind map” during the discussion that shows the linkages between program activities and resulting changes in the community. This approach is intended to help demonstrate the project’s impacts more holistically and to describe the degree to which different types of impacts are observed by project staff and community stakeholders.

Ripple Effect Mapping appealed to us both because we felt it would capture the impact of our network, and because we thought it would expose our members to a new tool they could use in other parts of their work.

REASN Ripple Effect Mapping Process

REASN has about 40-50 actively engaged members in our network and double that number more loosely connected to our work. As we thought about who to include in our REM sessions, we set out to invite people with a range of participation levels in REASN; some who had been a part of the network since its creation and others who were more recent participants. We also wanted to engage a group that represented the diverse lived experiences of our network members. We ended up with a group of fourteen people who represented a variety of professions, races, ages, and gender-identities.

During the REM discussions, participants from REASN gathered to reflect on the impacts of their time in the network. We did our best to make the process transparent so that members could learn about REM while doing it. The questions asked during the REM discussions focused on participants’ personal and professional growth, how REASN supports their racial equity work, and observations about outcomes of their work. Here are some examples of the questions we used:

- What is one important change that you’ve seen or that you’ve experienced personally that has come out of the work of REASN?

- What new or deepened connections have you made with others as a result of REASN?

- How has REASN helped you disrupt the myths of white supremacy and colonization?

- How has REASN sharpened your thinking about advancing racial equity?

- What have you gained from the relationships you’ve developed in REASN?

As we answered these questions, we placed our post-its on the wall, pairs shared out from their conversations and our evaluation partners took thorough notes capturing the impacts we were naming. The process felt very organic and not unlike a discussion we would have at one of our quarterly network gatherings.

The observed impacts were grouped into five main types of changes that had taken place because of participating in REASN:

- Building courage and confidence

- Fostering new ways of thinking

- Building a healing space

- Fostering connections and support

- Impacting how people are as practitioners

A Season of Transition

As we thought might be the case, REASN in now in a period of transition as we explore possibilities for a new fiscal partner and funding sources. Our Ripple Effect Map is serving as a key asset in this process, reminding us of the impact of our network and why it’s worth the work to sustain it and helping us tell the story of our work to potential partners and funders.

featured image found HERE

The Racial Equity Action Support Network (REASN) brings together racial equity champions and advocates from community, nonprofit, and government organizations across Minnesota. Sindy Morales Garcia and Kirsten Johnson of Courageous Change Collective serve as network guardians for REASN.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Power dynamics: A systemic inquiry

Why this article? Purpose and position

The word power keeps popping up wherever I turn. Through my ten years of doing my doctorate action research it was all over my notes and reflections. I kept pushing it out of what I was writing about and feeling scared to even go there as if the power of it itself was too much to face or to look at, as if it was just too complex and unknown. In the end I could not ignore the question and did reflect on what it meant for the work I had been doing. I concluded that the field of systems change did need to really integrate it more into its work. Fast forward a couple of years and the question kept on slapping me in the face, not literally but in the questioning of who you choose to facilitate a session, how you frame the work, make decisions and so forth — saying to me — come one you said it was important to what the hell are you doing about it!

This article therefore is trying to pull together some of the thread of the last four or five years of looking at the journey so far and what I have learnt. I have put off publishing this for eighteen months as if the final answer or way to present it will come, but that I also realise is a putting off — so here is some of the messy journey of stumbling around in the dark.

This article there has a few elements to it.

- Firstly how the issue of power relates to the systemic sustainability challenges we are facing — from climate change, deep inequalities that through the mirror that is our time in Covid has been seen even more acutely and how we might see the way they interrelate and are part of the same issues.

- Secondly exploring the concept of power and how it relates to systems change;

- Thirdly, looking at some of the insights about what makes up the dynamics of power, that are based in both our histories, and wider context as well as how that manifests in us individually and needs work all levels;

- Finally starting to explore some framings of the strategies we might take to work with power.

I am trying to explore this topic from a systemic perspective, by which I mean exploring the dynamics and deeper rooted mental models that affect them and how they play out in the world. In a previous article I explored the multi-dimensional elements of power which I will not repeat here.

I also want to acknowledge that I am a white woman born and living in the UK, I am middle class, went to a private school and have a postgraduate education. I am a Director of a charity and have a comfortable life. I have a huge amount of privilege, rank or social and psychological power. Over the last couple of years I have realised how much of this I still need to understand and do. I am still on a massive journey to explore what this means for me, my work and those I work with and most importantly how we best act on this exploration. I acknowledge that this writing in and of itself addresses the issue through my own lens of knowledge and privilege, intellectualising it, exploring it through tools and approaches that I use. And yet this is the only way I know how to unravel what I have been experiencing and the challenges that we see. I am trying to live life through inquiry, to explore what is emerging in front of me, to actively lean into what is needed, to learn from the experiences, to read and learn from ideas that are out there and to ask myself how might we enact these in practice, for myself, for the work that we do and for the world.

So I invite you readers to enter into this journey of exploring with me and am interested in your own reflections and feedback.

Why power is a systemic challenge; where does it show up and why is it a problem?

There might be many ways to understand this dynamic, we could start with questions of poverty, inequality and all social and environmental challenges. For example exploring the issues of climate justice demonstrates and shows the effects of our current frame of power. The causes of climate change have predominantly been created by those who have used and burnt carbon for their accumulation of wealth and the improvement of their lives. This meant that they drove their dominance in the global economy, from the industrial revolution to the perpetuation of colonialism. Whilst the effects of climate breakdown are being more acutely felt where the most vulnerable live, whose development and ways of life have been hampered and repressed by power dynamics in the past. It raises questions about who has and is benefiting, where is the burden and how can we move to a more equitable and fair world? How might we transition is a way that is just and fair (a just transition)?

At the heart of these issues is dominance — of one society, nation, peoples — where their policies and practices acquire control over another — through literal means — from slavery, use of resources, exploitation, occupying land. It starts from a place of difference, but is acted on from a sense of superiority, exemplified through racism and other oppressive behaviour across all forms of intersection.

The current exploitation of our planet and people are manifest from power dynamics that have been perpetuated and continue to be so in all our systems. Many of the historical drivers of our ecological unsustainability — of extraction, consumption, capitalism — are the other side of the coin of the issues of colonialism, white supremacy, racism. Understanding power therefore might help unlock how we might transition to a world that is not only sustainable but just and regenerative that is has the capacity to keep distributing resources in a fair way. We in the sustainability field can no longer ignore these issues.

This diagram seeks to show how these different ideas and processes relate, how they are all part of the same dynamic. There are historical drivers and trends that have created the current world, a way to frame old power (which I will get to shortly). These manifest in issues that we see today in the world such as racism, under which are structural issues of inequality and privilege. I am proposing that these are all part of deeper power dynamics (that are informed by our perspectives). We are looking to understand how we transition to a future that is equitable and just and has power dynamics (new power) that are fluid, plural and understand life as a process.

How might we understand the concept of power?

Power is a contested term. The way we often use the word it assumes that it is about the power one thing has over another, be it explicit, or covert or unseen.

This first framing of power places it as a process of othering, by which we make others not the same as us, the noticing of difference and in the same breath we place value judgements of who is better, what is better and who has more power than others. This in turn starts to become embedded in our structures and our consciousness, so that structural racism or white supremacy exist.

Power as such though is simply the energy exchange between two things and so a second framing — I would argue a systemic one — starts to look at power through the eyes of our relationships, through the web of societies’ capillaries — that permeate the fabric of our existence. As such it also can be a motivator for what we do and how we do things, and has such power lies within us and can give us a sense of agency to change ourselves and things around us.

“We have the power over our own story” (Rushdie, 1991)

Power as such is not a static concept, it changes, not just who has it but also how we understand it through the course of history. Power operates within a perspective, worldview or paradigm. How we see power affects how we act with, on or from power. So it is vitally important to understand the position and perspective that we are coming from in order to understand power. For this article I will only use two — that of the current or old power of dominance and power over and that of the emerging new power — one that sees it more as the relational systemic flow.

How do we transition from a dynamic between us, now embedded in our structures, from one that has certain people, groups over others and which results in great exploitation of resources to one where we are living with just, fluid, plural, diverse relationships and where people have the sense of agency to also author their own lives?

Power and systems change

If we define systems change as the emergence of a new pattern of organising and power as a relational dynamic not a given state; then changing systems is all about also shifting power dynamics. Then in order to change systems and power dynamics we need to change the nature of our relationships and our ways of relating. As started to describe above, if we are to address issues of inequality, climate change, racism and all forms of social and environmental issues then addressing power dynamics is central to them all.

The current power model — or the pattern of how the system is structured is through coercive hierarchy and structures that are based in dominance, of power over and the relational dynamics we need to move towards is one that is systemic — by that I mean a way of living that recognises that life is change that we live and work in dynamics and fluidity whilst also recognising that this needs to be done justly.

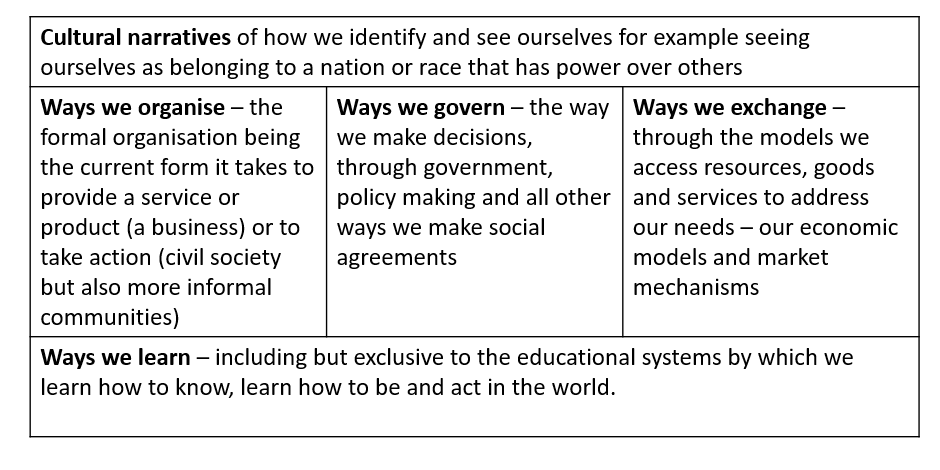

There are many ways we relate in society, where we have created societal structures around — each of which might be a route into addressing power dynamics. In society some of these foundational structures are:

[A note — not all power over is exploitative, for example in many hierarchical organisations, however if we want to address power that is then we also need to model what new relationships of power look like, so as to offer the potential for more healthy and flourishing relationships.]

What questions does it raise?

If I am saying power is an underlying dynamic and my overall inquiry question is — How might we cultivate systemic change? Then the question(s) relating to this exploration might be:

How might we transform society, its power dynamics, from the power over model that permeates today to a just form of relating and organising that is systemic?

- How might we change the nature of our relationships?

- How do we cultivate and be in relationship?

- Who do we work with and how?

What does this mean for us personally? In the projects that we do? What does it mean at how we transform society?

Insights in to what affects power dynamics

After exploring power as an idea and more importantly in practice over the last few years here are some insights into the dynamics of power from these experiences.

Although power is relational, we as individuals also have different positions in the web of social relationships. Having an awareness of your privilege and positionality and therefore any assumptions and bias you bring to any given situation is therefore critical to understanding power.

As we grow in relationships we do not grow straight and perfect. Different experiences and traumas, where unfair use of physical, psychological or social power has been used against you (Mindell, 2014), in our past determine how we grow from the inside out. These traumas are like knots or different shapes that develop in a tree that will continue to determine how it will grow and relate to others. These might be developed from how we are parented to the culture and society we grow within. This inner world, our psychology, plays out in our relationships and therefore can (re)create power dynamics that can perpetuate harm or injustices.

Due to our different awareness's, positions and life experiences we are all on different journeys of both understanding but also being impacted by dynamics of power. I have used the metaphor of yoga to help exemplify this. When we start doing yoga we have only a certain amount of flexibility, we are only so open. The way yoga is practiced is you stretch and move to the edge of what you can do, push in slightly but not too far and then relax, you transcend and integrate. You keep practicing and over time you open up to new movements and ways of doing things. This is the same for our addressing power, everyone has different levels of fluidity, openness, flexibility and ability to deal with these questions. This does not mean we cannot go on a more intensive yoga retreat or practice daily to get better practitioners.

Understanding our position and traumas requires inner work, that is to say working on the things that activate us or trigger us — that is something that might cause us to feel emotional not by the current experience but because it takes you back to something else in your past — that stop or hinders us from moving forward on our journey. Using the yoga metaphor again, if we had a bad angle injury it would affect what moves we could do. Our development of our psyche is the same and affects how we are in relationships, as facilitators and practitioners. Inner work aims to work on these issues and help us move with fluidity and openness.

The environment we find ourselves is also extremely important. Unsafe environments that we are not prepared for can cause more harm than good, be it an organisational or workshop setting. However we also need spaces that provide the conditions for bravery to work with issues that are uncomfortable and hard to address as this is not an easy journey. For this we need facilitators.

If we see facilitators role as bringing awareness to the world, sensing and working with people and their interactions, relationships and other dimensions so as to bring forward what the world needs of us we may look at the practice of “sitting in the fire” to get used to this uncomfortableness.

As a facilitator these environments can be supported by showing both vulnerability, the openness you can display in your own learning to model opening up for others as well as knowing your boundaries and taking accountability for your actions.

Finally all power dynamics are fractals, that is to say that a pattern that is happening at a smaller level will be happening at a wider scale and vice versa. For example a dynamic that is happening between two people might also be seen within the team and then again within a wider network or society as a whole. Therefore if there is a pattern of power that has not been addressed by a facilitator team it will start to play out into the workshop and equally where an organisation is not addressing power issues themselves they are unlikely able to be addressing it in the wider systems they are trying to change.

What does this mean for the work that we do?

So if these dynamics and patterns are playing out at all scales what might some (not all) strategies for how we address the way that we might relate?

Minimise power-over

I am going to start with this framing as I feel it is the hardest one to deal with. Coming from a position of power and privilege it is critical that this does not get side-lined. Donella Meadows in her paper — Leverage points: places to intervene in a system describe how often address a dynamic by looking at solving the problem rather than looking at the dynamic that is perpetuating it. For example anti poverty programmes are weak negative feedback loops, trying to balance out the stronger positive feedback loop of a systems that brings more and more “success to the successful”. In terms of relational dynamics it is far more effective to weaken the positive loops — in this case minimising power-over relationships.

I will risk repeating myself and highlighting the two insights from above and how we must also look at them as strategies for change

- Position awareness — individually, organisationally and at any scale. Acknowledge the power and privileges we have, for example what knowledge we are privileging. Be prepared to be open about it, find ways to talk about it, be humble with what you are doing — practice vulnerability.

- Understand and deal with our triggers and traumas — so that we start the learning journey of not creating harm (again at all levels). Become really comfortable with uncertainty, being uncomfortable so you can turn towards and be centred in challenging situations.

- Be open to having difficult conversations

- Practice letting go — what would it mean for the organisation to not exist, to write its own exit strategy? What if you personally were to live on a lower income, with less consumption? This also means getting out of the way of others.

- Transition power and resources — This means working with those in power and hold decisions over the resources to use their power to shift where and how decisions get made. For example funders hold a lot of power in change systems or policy makers across society.

- It sometimes takes a generation to shift a system as mind-sets and power shift. Consider what the trajectory is for people giving up or more shifting their (supposed) power, support shifts in identity, their sense of who they are in the world. Help them become enablers, elders and play a role with those who have more power then them as part of the transitional process. What are the rituals and ways we might celebrate, acknowledge the journey.

- Change the narrative that helps build this perspective shift, whilst also recognising that language is a form of knowledge and power. This might require doing discourse analysis to support reframing.

- People cannot be coerced, invite people in to develop the collective mandate — start using participatory methods to do this (see next section). I am not however saying that there is not a role for calling out or campaigning where harmful practices are pointed out however we do need to understand them in an ecosystem of changing relationships.

Set the conditions and enable power-with

- If you are facilitating these processes really model behaviour of being open to what might emerge and the way forward. Like above — be acutely aware of your power as holding a space, ensure that you do your inner work.

- Use the power that you do have to demonstrate and use participatory methods for decision making, working together and building coalitions. This means setting the container for working and relating, through being clear about mandates, roles and responsibilities and not assuming everyone knows how to work from the get go. Ensure there is participation in the production of knowledge and learning.

- Creating safe or brave spaces for people to work together. This might be preparing people to be able to be in the room together, investing time so that new ways of relating can be found. Change can only happen at the speed of trust.

- Transparency is critical for this, allowing the process to be seen and be open to be called to account and criticism — actively inviting in alternative views, seeking wisdom in the minority to improve the decisions and processes.

- Create liberating structures, new ways of organising, regenerative cultures and rules that enable self-organisation — there are different examples and literature on these different methods — for example Re-inventing organisations.

Enable power from with-in

Much of this is also a repetition of what has been said above — supporting inner work, addressing trauma and triggers and ensuring resources are put into this work.

- Place high value on lived experience as supposed to learnt experience — which usually manifests in approaches to learning and capacity building that are transactional, delivered to people not with. Value the learning process over the knowledge accumulation.

- Follow the principle with not on. An example of this might be not creating personas of different views and perspectives but actively bringing real people into design and futures processes.

- Work is needed in the liminal spaces, find the people who can be the bridges and give them resources both time, money and safe spaces to support the transition.

- Create transitional decision making forms — for example a shadow board, to build agency to transition power

- Devolve decision making — through the above strategies ensure that the decision happens closest to the impact

- Really understand the process of personal change and what that means societally– and recognise that everyone has their own stretch and time requirements

This list of actions are by no means exhaustive, they also do not address some of the actions needed for addressing some of the specific issues such as racism, but its aim is to start to think about relational strategies that might be beneficial to all these issues. Please do also share with us others you might have and what is missing..

So where does this leave me?

I am still struggling with the process of shifting the dynamics of power on a daily basis, from every interaction I have as a leader, teacher, facilitator, director, white UK woman, parent even, trying to bring awareness to what I am doing. How I have to both step up, use my power, stand up for what I believe in and set the conditions for others and in the same breath step back and get the hell out of the way and just shut up!

How I still feel rage or anger for people not doing enough and how it bubbles over and out as I don’t know where to always put those feeling and yet trying to heed my own insights that its a journey and you cannot undo centuries if not millennia of harm and oppression that has existed in the one moment you have in front of you. And yet you try and do something and then you know every action is just not quite enough or good enough and again you find yourself fumbling around in the dark.

How I also know there is still so much that I do not see, so much of our unconscious so much of that we are all still playing the game of the current system and thinking that we can somehow change it, that its forces and dynamics are still as yet unknown. How we are complicit every day in its powers.

And so one promise I will try and commit to myself is that I will not keep ignoring the calling of this question both in my own learning and in my practice and that of those I work with. That all I do know is that I need to keep coming back to it as in itself it also has an illusive enticing power of intrigue to the flow of life itself and how it has both caused great harm and yet if relationships are also what gives us great joy and a sense of flourishing it also has the potential to bring healing.

Many of the ideas in this article have been influenced by my reading and training in Processwork — including the work of Sitting in the Fire by Mindell. I am also grateful for those those I have been co-inquiring with over the years my colleagues, co-inquirers and funders, at Forum for the Future, School of System Change, Living Change, Boundless Roots and Lankelly Chase Foundation and New Girls Network.

Originally published at School of System Change

Director School of System Change, Forum for the Future

@annasquestions

Anna is passionate about designing and facilitating systems change programmes that support people, communities and organisations to transform their practice.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Trust Emerges Over Time

Imagine a research-intensive organization where scientists should be sharing what they learn, and the official company policy is to share information and expertise among public and private partners. However, the company is ‘downsizing’ and layoffs are based on performance reviews. If one scientist helps a peer develop a patented product, and as a result the peer gets a better annual review, then the former may end up losing their job during the next round of layoffs. This was the situation I found myself in a decade ago.

Sharing knowledge was not a good personal strategy in this work environment even though it was official policy and was the focus of our project. We could not achieve our project objectives because systemic barriers pitted workers against each other in order to remain employed.

In this case, financial rewards for patents impeded learning, and in the end halted any knowledge sharing. In complex systems, the solutions are never simple, but our only hope is learning how to learn better and faster — individually, in teams, as an enterprise, and as a society. If we want to promote learning through knowledge sharing we should first look at what is blocking it.

Stan Garfield recently posted 16 reasons why people don’t share their knowledge. Of these 16 reasons most are due to a lack of information, tools, incentives, or motivation. These are systemic barriers to knowledge sharing. Only a few are due to a lack of skills or knowledge, which could be addressed through formal, informal, or social learning.

In my experience the core issue is trust, which Stan outlines in his second point.

2. They don’t trust others. They are worried that sharing their knowledge will allow other people to be rewarded without giving credit or something in return, or result in the misuse of that knowledge.

When trust is lost, knowledge fails to flow. When knowledge flow is stemmed, trust is lost. This happens in organizations. It also happens at a societal level. Networks of trust are what create value at all levels for human society.

“It is important to stress that we are all connected through a complicated net of trust. It is not as if there is a group of people, the non-experts, who have to trust the experts and the experts do not have to trust anyone. Everyone needs to trust others since human knowledge is a joint effort. The most poisonous effects of social media may not be the spread of disinformation per se but the undermining of trust that comes from anger and division. It is well known that low levels of trust in a society leads to corruption and conflict, but it is easy to forget the very central role that trust plays for knowledge. And knowledge, of course, is essential to the democratic society. As the historian Timothy Snyder has said, post-truth is pre-fascism.” —Why do we resist knowledge?

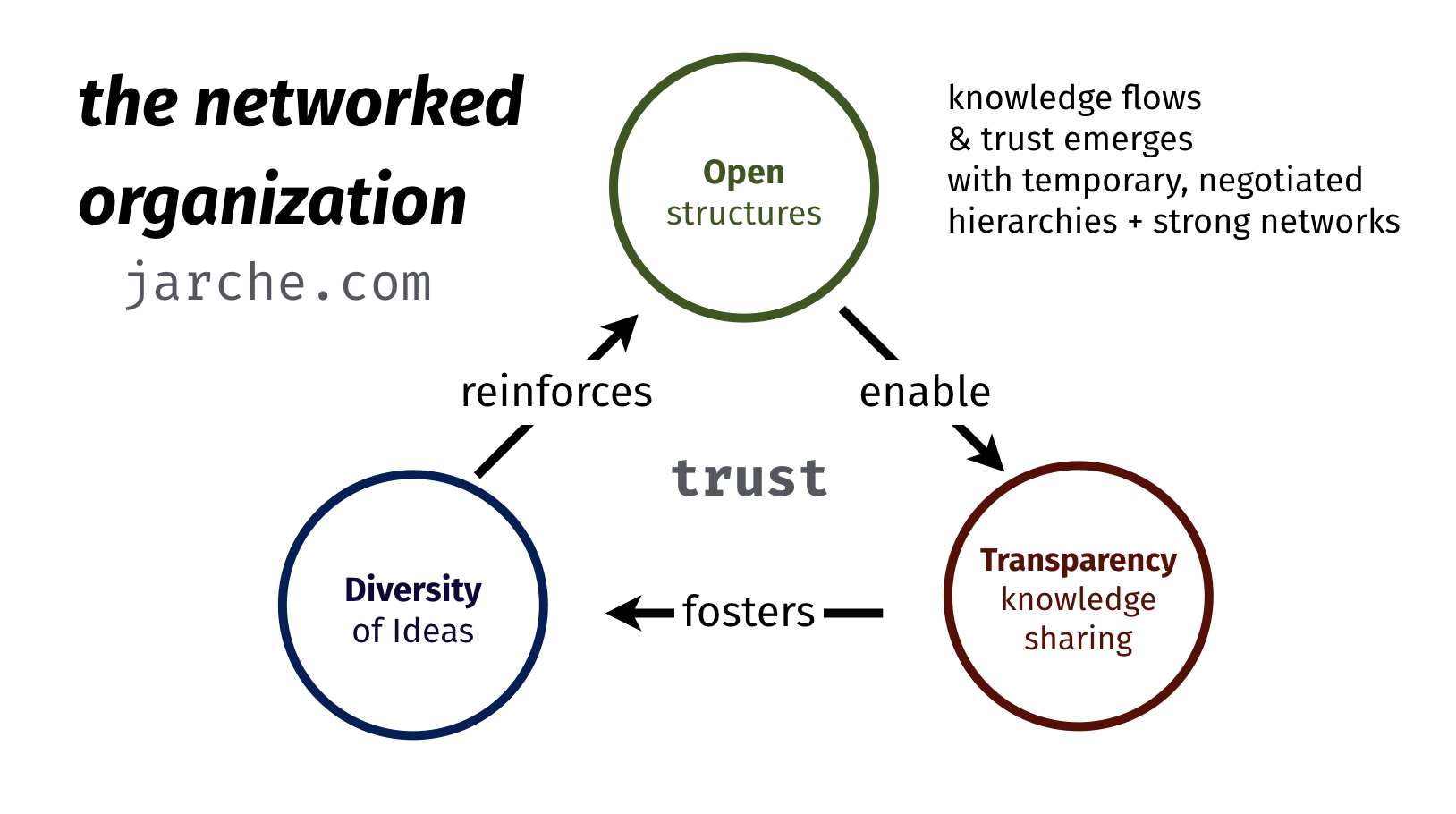

Openness enables transparency and knowledge-sharing, which fosters diversity of opinions, and these reinforce social networks. First we create open structures, more networked than hierarchical, with freedom to move across teams. Then we promote transparency by discouraging gatekeepers and identifying knowledge bottlenecks. This openness can encourage diversity of ideas and people. It is only over time that trust emerges. If knowledge sharing is the issue, take a good look at how the system is blocking it. Only then look at individual capabilities.

Originally published at Jarche.com

Harold Jarche works with individuals, organizations, and public policy influencers to develop practical ways to improve collaboration, knowledge sharing, and sensemaking.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

A Journey Toward Becoming an Anti-Racist and Multicultural Organization

A note from the editor: This post is a letter sent on April 16th from The Wallace Center at Winrock International to it's friends and colleagues. Network Weaver asked to republish this letter, and the accompanying resource, because, like The Wallace Center, we also see the potential for transformational impact in sharing a story of awakening to organizational inequity and enacting systematic change. The authors write: "By sharing our own story, we might encourage others to interrogate their own blind spots, rebuild new systems and processes that prioritize equity, and shift organizational cultures"

A couple of years ago, our team at the Wallace Center undertook an honest assessment of our organization’s history, values, culture, operations, and programs to determine where we landed on the Continuum on Becoming an Anti-Racist Multicultural Organization. What we realized and learned through that reflection was painful and real, but it marked the beginning of our continuous efforts to learn, grow, and center racial equity in our organization and work.

In the spirit of accountability, vulnerability, and transparency, we want to share the Wallace Center’s Journey Toward Becoming an Anti-Racist and Multicultural Organization.

Unfortunately, the timing of this message coincides with the continued brutality against Black and Brown people at the hands of the police. This week's news reports out of Minneapolis about Daunte Wright's murder and Derek Chauvin's ongoing trial demonstrate the urgency for systems change. We will never achieve economic, environmental, and social justice without first achieving racial justice.

Learning from our past.

For decades, the Wallace Center didn’t acknowledge or address the historic and current racism that underpins our farming and food systems. We sat on the sidelines, and our passivity and complacency reinforced racism and racial inequity in the food system and in the movement to change it. Partners and funders substantiated this hard truth; that we as an organization had a lot of work to do to meaningfully center racial justice and equity in our food systems change work and dismantle white supremacy culture within our team and parent organization, Winrock International.

That reflection marked a turning point for our team. Since 2017 we have been in process to put our intentions of being a racially-just organization into practice. This has been and continues to be both a personal and organizational journey for our staff. As a predominantly white team within a predominantly white organization – historically and today – we undertake this work with a sense of humility and from a position of learning rather than knowing. Institutional inequity and white supremacy is deeply entrenched in our organizational structures and systems and is pervasive in the domestic non-profit field as well as the international development sector we are embedded within at Winrock International. This includes not only our own organization, but also those with whom we affiliate, including those who fund our work.

Moving forward, together.

This document provides a summary of our journey thus far towards centering racial justice and equity in our organization in a meaningful, authentic, and accountable way as embodied in our racial equity commitments. There are many resources linked throughout the document that have been instrumental in fueling our internal work and we hope this will be helpful for others. It is not a “how-to” guide – we are not experts in advancing racial equity in organizations – but rather a perspective of how we’re taking steps to undo racism in our organization. One such example is through the Food Systems Leadership Network’s Network Weavers conversations, in which members virtually connected to discuss ways in which our work could contribute to and advance systems change.

We can’t do this work alone.

Our learning journey has been encouraged and supported by the work of other organizations and leaders who have inspired and challenged us. We have kept much of our process and learning internal to the Wallace Center and our parent organization, Winrock International, which has more recently started the work towards equity. It is our work to do. After the killing of George Floyd last year, followed by the international uprising against institutional and structural racism, we felt that our Wallace Center journey could be a helpful reference for Winrock International and other (mostly white-led) organizations who are reckoning with their own complicity in perpetuating white supremacy and racism. By sharing our own story, we might encourage others to interrogate their own blind spots, rebuild new systems and processes that prioritize equity, and shift organizational cultures. We also agreed that sharing our journey and our commitments publicly would enable others to hold us accountable as we work towards becoming an authentic and explicitly anti-racist organization.

We want to specifically thank The Justice Collective for their partnership and support of our team, and honor the hard work and commitment of each staff member at the Wallace Center who has contributed to our evolution. We are still very much in the thick of it – the journey toward our collective liberation has no endpoint – and invite your feedback, reflections, and questions.

In solidarity,

Susan Schempf and Pete Huff, Co-Directors, Wallace Center

The Wallace Center develops partnerships, pilots new ideas, and advances solutions to strengthen communities through resilient farming and food systems. We serve the growing community of organizations, businesses, and public agencies involved in building a good farming and food system in the United States. Our program work focuses on advancing collaborative, regional efforts to grow and move good food – food that is healthy, regeneratively produced, and recognizes and builds value across the entire supply chain, from producers to farm workers, aggregators, processors, distributors, buyers, and the community based organizations supporting the food ecosystem.

featured image found HERE

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

by Susan Schempf and Pete Huff, Co-Directors, Wallace Center

This is How #WeGovern

Last year, we witnessed the near collapse of our collective systems—the systems that should be sustaining us when we need them most.

And the truth is, they’ve been failing us for generations. Today, amid a global pandemic, sustained violence against Black lives, brazen attacks by white supremacists, climate catastrophe, and pervasive economic injustice--we can see what Black and Indigenous folx have been saying for generations: these systems were not designed for us.

It is time they were.

We Govern is a roadmap for that creation. This foundational set of agreements were written by a group of predominantly Black, Indigenous, people of color across the US, to guide how we make the decisions that impact all of us--including how we choose to live together, use our resources, and build systems rooted in radical care.

It is an invitation to redefine governance.

Governance is the process by which we determine the norms and rules that guide everyday life and behavior, and we—all of us—have a role in it. Whether it’s through our personal lives as parents, friends, neighbors, caregivers, and stewards; or in our work as leaders and decision-makers—the choices we make each day determine our emergent future.

As our FAQ page says, “Whether deciding if it is worth it to struggle with a kiddo to eat broccoli, facilitating a healing conversation among friends, or creating a spending plan for clean energy in your town, the act of making choices for our collective wellbeing is governance.”

Governance is about making decisions together—at small and large scales—about the things that matter to us and impact our lives.

Today, together, we envision a more just, harmonious, and thriving future that refuses to leave anyone behind. We envision a world where we tend to ourselves and each other knowing that the choices we make each day add up to the world we’re building. We imagine systems of radical care in keeping with our sacred responsibility to care for future generations and the earth we share. The world we want is rooted in mutual care, deep relationship, dignity, and safety — for ourselves, for each other, and for the natural world.

Now, in the early part of 2021, we find ourselves still deep in a pandemic, clambering to stabilize the harms of last year, as we continue moving toward a still uncertain future. In this moment, a vision of another world is more urgent — and more possible — than ever.

By planting the seeds of commitment to collective care, we can create the world we want through the choices we make. WeGovern is an invitation to align our actions with our values—to commit to the foundational agreements we need in order to carve a path toward what’s possible.

The world we want — a world where all beings can thrive — begins with each of us. And it can start now.

To be counted among those who are embracing the sacred responsibility to take action and care for our collective wellbeing, sign on here.

Access the WeGovern Media Toolkit HERE or visit WE-Govern.org directly.

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources? DONATE HERE to assist us in continuing the shared vision & collaborative campaign for equity, justice, & transformation.

Is Defunding Police Departments Right for Your City?

Is Defunding Police Departments Right for Your City?

Will it Lead to Sustainable Success or Catastrophic Failure?

People around the world are protesting against racism and police brutality. The system is breaking down (or in the throes of self-correction, depending on your point of view). One solution that has been suggested is to defund police departments. It is unclear, however, whether defunding is the best approach for all cities.

Arguments against defunding suggest that it will lead to greater racial inequality and harm to the community as poor neighborhoods organize around criminal gangs. Some fear that removing the devil we know will lead to the arrival of seven that we do not. A wide variety of arguments in favor of defunding range from the relatively simple to the relatively complex. Each of them is claiming that their plan will lead to greater social justice and less violence.

Despite the range of opinions, two things are certain. First, things cannot continue as they are. There must be change and the change must be substantial. Second, the path to change is not clear, there is a veritable cacophony of voices and opinions on which way we should go.

In this article we will briefly explore our chances for successful change based on our existing understanding of the situation. Then, we will suggest a process for moving forward at the local level with a few key points to keep in mind for maximizing our chances for successfully creating communities that are safe, prosperous, and just. The first question is “do we understand the situation?” The short answer is no.

How do we know how much we know?

One warning flag about our lack of knowledge may be found in the halls of academia. A search for scholarly papers on the topic of “defunding police” found only seven publications. Compare that result with a search for papers on “police brutality” which found nearly sixty thousand publications.

Do those thousands of publications provide us with an effective understanding of police brutality? Are we able to eliminate police brutality? Obviously not. So, how do we think that we can solve the more complex problem of defunding police to improve safety and justice in our communities? It seems we have a vast quantity of knowledge, without much quality or usefulness of knowledge.

Of course, the academic world is not the only repository of knowledge. There are several web sites and articles providing suggestions for finding justice by defunding police. These include “For a World Without Police” and “Transform Harm” with more articles published on other sites almost every day. Each is different with alternate suggestions for action ranging from reducing police use of military hardware, to disbanding police departments.

One case that is increasingly mentioned as an example of successful de-funding is Camden, New Jersey. In that situation, however, the police department was disbanded and then re-formed. There is no guarantee that Camden faced the exact same situation as your city or that the Camden solution will prove effective in your city.

While reasonable people might argue forever about the relative merits of the many plans and few examples of success, we cannot argue forever – justice should be swift. However, justice should also be sure. The question becomes, “How can we predict if a plan might work?”

Research in the science of conceptual systems provides a method for evaluating those plans according to their internal logic structures. Let’s look at one, reasonably simple, plan for defunding the police to provide an example of how the structure of our knowledge might be understood. From a recent article we create the following diagram:

Thanks for the free online mapping platform to: https://www.plectica.com

Here, there are seven boxes – each representing a concept that is relevant to the topic of defunding police departments. They are connected by arrows representing causal relationships. For example, the more community patrols in a neighborhood, the less need there will be for police (and, presumably, less violence and more justice for all).

We can measure the structure of this knowledge by first counting the number of “transformative” concepts (those have more than one arrow pointing in to them). Here, the only transformative concept is “Less need for police.” Next, we count the total number of concepts (seven). Then, divide the transformative by the total to get 0.14. Thus, we can say that this knowledge is 14% structured and so has about a 14% chance of success (assuming that each of those causal arrows is supported by good data from previous research).

There is nothing worse than a simple plan.

To have a better plan, representing more useful knowledge, with a better chance of success, we need a map that has more boxes and more connections.

More pragmatically, the structural weakness of this diagram can be seen starting with its “daisy petal” arrangement. Imagine each box is being run by a different organization. All of them competing for funding, each of them ready to take credit for success but point the finger of blame at the other five groups if the plan does not succeed. This arrangement almost guarantees that the many groups will be in conflict with each other instead of cooperating for common and interdependent goals. Because, working in their silos, they are not collaborating as an effective network should.

This kind of “daisy fail” can be avoided by following two parallel paths of developing more structured knowledge on one hand, and by using better tools of government on the other. Both of these require communication and collaboration.

The “tools of government” path means deploying the best approach to find success within each box. For example, to improve our mental healthcare system we might consider providing grants, contracting those services out, mobilizing community volunteers, or any one of many different approaches. The choice of which tool to apply will be based on the appropriateness of that tool to the specific community. That choice, of course, would be made by the careful consideration of a diverse stakeholders. That means reaching out to find an ever-expanding circle of stakeholders and litening carefully to their concerns, insights, and ideas.

The second path is to improve the structure (and so the usefulness) of our knowledge. Here, there are a few basic strategies. First, we want to integrate research from multiple fields of knowledge. As mentioned above, there are untold thousands of research papers available; what we need to do is synthesize them. The second strategy is to access and integrate knowledge from a diverse range of stakeholders (black, white, police, non-profits, government agencies, social workers – more diversity is better). The process of collaborative integration accelerates our shared learning.

While some may see that as a recipe for confusion, their many insights can be integrated effectively using a “practical mapping” approach that has proved effective in creating more structured knowledge. Looking back at the daisy diagram above, we want to understand how all of the boxes may be connected. If we do it right, each organization will be working to support the others; and, will be accountable to the others. In short, creating a collaborative action network.

These parallel paths to success are guided by ongoing research into the “structure of knowledge” that shows how we can develop policies and plans that are more likely to succeed. Also, increasingly researcher are newer “tools of government” that are providing new ways to deal with old problems. Together, these tools, and the knowledge for how they might best be applied in each local situation, suggest a path forward that is likely to have sustainable success.

Instead of advocating for “bandaid” approach devoid of real change, or a “defund the police today” approach of immediate action, we would suggest an approach that is likely to lead to successful change in less than a year as follows:

- Understanding the situation (local facilitators use the practical mapping approach to generate a shared understanding among diverse stakeholder groups and scholarly research).

- Identify where solutions have been found and adapt the appropriate tools for each locality (using the map from step #1, carefully consider the range of tools for each part of the situation and choose the best tool for action).

- Apply solutions in parallel with existing police work (using insights from steps one and two, begin implementing tools being sure to identify how actions of each part will support other parts).

- Evaluate and return to step #1 (this will include tracking measurable results and reporting them with full transparency through community meetings and online dashboards).

With competent leadership, the first two steps should require less than two months each to create an effective map and choose the best tools. With tools in hand and a shared plan, step three may begin almost immediately with activities easily coordinated based on the map. Results may require a few months to manifest; however, they certainly should require less than a year. Data collection will be ongoing. And, with that data, participants can revise the process as needed.

To summarize, we have a great quantity of knowledge but that knowledge is not have a high quality. It is unstructured and so provides only the pretense of understanding. Thus, as it stands, dramatic efforts to defund police have about an 86% chance of failing to reach their goals.

Likewise, it should also be noted, that with less structure and less chance of success also comes greater chance for unanticipated negative consequences. So, the concern about gaining seven devils we don’t know, just to get rid of one we do, seems quite reasonable.

This kind of failure has been seen before. Even policies that are well funded and broadly supported, such as the “war on drugs,” have failed to reach their goals. Worse, they have spawned a variety of new problems such as sending more people to prison which results in increased costs to taxpayers and the destruction of families.

Because action should be taken to advance justice for all, this post has outlined a path of collaborative communication and learning for toward improving knowledge for effective implementation that gives us the best chance for success within a reasonable time frame. The results may not lead to any one group being perfectly satisfied, but they will lead to better, safer, just, and prosperous communities for the benefit of all.

About the Author

Steven E. Wallis, PhD

Director, Foundation for the Advancement of Social Theory (FAST)

Capella University, School of Social and Behavioral Sciences

Researching and consulting on policy, theory, and strategic planning

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5207-603X

Dr. Wallis is a Fulbright alumnus, international visiting professor, award-wining scholar, and Director of the Foundation for the Advancement of Social Theory; researching and consulting on theory, policy, and strategic planning. An interdisciplinary thinker, his publications cover a range of fields including psychology, ethics, science, management, organizational learning, entrepreneurship, policy, and program evaluation with dozens of publications, hundreds of citations, and a growing list of international co-authors. In addition, he supports doctoral candidates at Capella University in the Harold Abel School of Psychology. Following a career in corrosion control engineering, he earned his PhD at Fielding Graduate University and took early retirement to pursue his passion – leveraging innovative insights on the structure of knowledge to accelerate the advancement of the social/behavioral sciences for improved practices and the betterment of the world. His textbook, with Bernadette Wright, “Practical Mapping for Applied Research and Program Evaluation” (Sage Publications) provides unique and effective approaches for developing new knowledge in support of sustainable success for businesses, government, and non-profits programs working to improve measurable results, individual lives, and whole communities.

featured image: DOUG MILLS /NYT