The radical potential of healthy shame… to return us to belonging

This is the paradox: to reach transformation, we must let go of the aspiration for transformation. As psychologist Carl Rogers put it:

The curious paradox is that when I accept myself, just as I am, then I can change.

While I accept this truth intellectually, and it feels doable when it comes to my self-transformation work… I haven’t yet figured out a way to embody it in integrity and authenticity when it comes to my work for social transformation. David Kelleher names the tension I feel:

If you’re going to work with people for change, you have to love them… I’m still stuck with the contradiction of loving someone and making demands on their behavior in the name of justice.

It feels like I’m being asked to let go of my commitment to justice… in order to honor my commitment to justice. I don’t know what to do with that. So today I want to explore a controversial idea: the concept of “healthy shame.”

TL;DR: Toxic shame tells us we don’t belong, and offers no path back to belonging. Healthy shame reminds us that we belong, and warns us when we transgress a social norm that threatens the collective: it invites us to change our behavior, not our core sense of self. We need to cultivate the capacity to heal from toxic shame, and build resilience to tolerate healthy shame… and take action to repair harm and return to belonging. There are four steps: show up with compassion for the other; help them practice self-compassion; co-regulate to feel safe in their bodies; support the practice of new behaviors. To come into right relationship with shame is to exercise power: a tool we can use in service of justice, and to create a world where everyone belongs.

Transform behavior, not people

This feels important to underscore: by virtue of the miracle of our existence, like all beings, humans are perfect exactly as we are. It’s our behavior (at an individual, collective, and systemic level) that needs to change.

When I first started writing this post I paused for a couple days to do another deep-dive into the literature on shame and guilt (building on this post, where I first named the acceptance/transformation paradox, and this one, exploring more collective accountability questions). I want to update/amend my previous conclusions to explore the transformative potential of healthy shame.

To be clear: the way our dominant culture wields shame is incredibly toxic: any shame that contributes to paralysis, that inculcates in its target a fundamental sense of unworthiness harms our goal of enabling transformation. That is NOT what I am talking about here. There is shame that is associated with trauma, and there is shame that is associated with healing and resilience… it is this fraught latter terrain I want to explore today.

Because shame (and guilt) are social emotions that have to do with our sense of (and right to) belong, the core difference that distinguishes healthy shame from toxic shame is whether there exists the possibility of returning to belonging. If the purpose or function of shame is to exclude without offering a path to redemption, it is toxic. If instead the purpose is to illuminate a harm and invite repair… it can serve a healthy function. I appreciate Joseph Burgo’s treatment of the subject, where he explains:

Helpful shame always leaves room for improvement rather than making someone feel fundamentally worthless, with no hope for growth.

This to me is the difference between feeling shamed (you are making me feel something, which may or may not register as fair) and feeling ashamed (I internalize the assessment and agree I have done something I regret; a third party may not need to be present or aware of my transgression in order for me to feel ashamed). Annette Kämmerer explains:

We feel shame when we violate the social norms we believe in.

In this rendering, to feel ashamed is to feel the pain of finding ourselves out of integrity with our own values. As Mark Manson notes:

Our values determine our shames.

Shame defines the conditions of belonging

Shame is a social emotion: it is the enforcement mechanism for belonging. Burgo again:

Human beings developed the ability to feel shame because it helped promote social cohesion.

Social norms define the boundaries of belonging: they are the set of agreements that allow us to function and live in community. In its social expression, shaming alerts community members that they have transgressed a social norm, and invites them to take corrective action, to repair the harm. I love Miki Kashtan’s explanation of how shame functioned in pre-patriarchal societies:

When the behavior of an individual threatens the ongoing cohesion or functioning of the group, and only in those circumstances, that’s when shame emerges as a mechanism for protecting the group from the threat of an individual taking action that might endanger the group.

Burgo agrees:

Our evolutionary ancestors used shaming and shunning to encourage change, to help tribal members reform their transgressive behavior and then reintegrate.

I think of it this way: love is unconditional; belonging is not. Love (for your self as a simultaneously perfect and flawed human) is unconditional; belonging (which includes how you behave in a collective) is conditional on you adopting the pro-social norms and behaviors that allow the collective to thrive. I loved Naava Smolash’s comment on my last post taking up this topic, where she named this tension inherent in the promise of belonging:

The one condition of belonging that makes true belonging possible, is the willingness to excise those who genuinely do not care about others or are unwilling to challenge their own conditioning into dominance.

It is perhaps easiest to understand the value of shame by imagining its absence: to be “shameless” is not a good thing; it’s associated with sociopathy. I’m reminded of that classic line in the McCarthy hearings, which I hear as another way of saying: are you impervious to shame?

Using—and choosing—healthy shame

I believe there is a role for healthy shame to help encourage people to adopt these new norms… but it’s a delicate dance. Take for example the emerging awareness around micro-aggressions: misgendering or deadnaming someone for example, or inadvertently deploying a racist stereotype. I think it’s healthy and necessary to feel that initial sting: it’s to become aware that I have caused harm, and to feel shame. And of course I don’t want to stay in that feeling: it’s deeply uncomfortable. We tend to respond in one of three ways (and let’s assume for the sake of argument that the norm is a positive pro-social norm, as I believe these are):

- Internalize the shame without self-compassion; this transmutes healthy shame into toxic shame: I’m a terrible person, I don’t belong. This not only misses an opportunity for transformation, but it also leaves the harm unrepaired as I retreat into myself and disassociate from the person/people experiencing the impact I caused.

- Reject the new norm and refuse to feel shame: I don’t believe in pronouns, and I refuse to take accountability for my impact. Often this strategy is accompanied by blaming/attacking the person who made visible the transgression: instead of attending to impact, we cast ourselves as victim for not having our intention seen/honored (Jennifer Freyd coined the term DARVO to describe this approach, often used unconsciously). This too misses the opportunity for transformation and for repairing harm. I resonate with Heather Plett’s description of what’s going on here:

People who’ve convinced themselves they are good people… are suddenly sent into spasms when their biases and blindspots are revealed. They can’t fathom the fact that they are capable of causing harm. They haven’t been equipped to hold space for their own shame. Subconsciously, they’re terrified that they will be abandoned and, at worst, banished from the kingdom.

- Accept the new norm, move from feeling shamed to feeling ashamed, and try to do better. To practice self-compassion (now I know, I can do better) and to exercise responsibility for impact (I’m sorry) and accountability to repair (how can I make it better and avoid causing harm in the future?)

Our goal, of course, is to support people in choosing the third path. And: we also want to exercise individual and collective discernment about which norms we want to embrace/internalize, and which we want to rightfully reject.

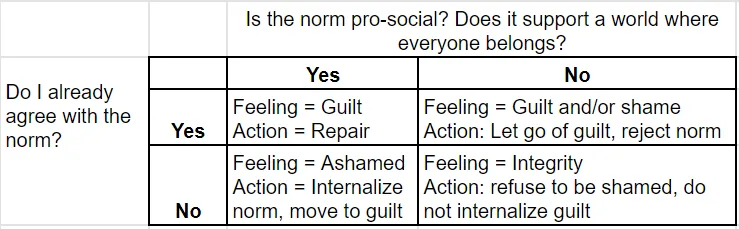

There are many existing social norms that I think are harmful and incompatible with a world where everyone belongs: in those cases, I think it is incumbent upon us to reject the norm and decline to feel the sting of shame. For example, should a man choose to wear a dress, in a world where everyone belongs that’s a perfectly valid and beautiful choice: he should refuse to be shamed for it (and we should refrain from shaming him). Because I’m a nerd, I made up a 2×2 matrix trying to illustrate this.

In this understanding, guilt only occurs when you already accept/agree with a norm: by definition, you can’t feel guilty for something you didn’t know was harmful, because you couldn’t have acted differently. In the case of encountering a new norm, the initial feeling is shame, which you can then transmute into guilt by accepting the norm and committing to repair. Shame researcher Dr. Stephen Finn summarizes his findings:

The goal is to help people tolerate shame and move to guilt… healthy shame is guilt.

Four steps: from shame back to belonging

I love Stephen Finn’s reminder here:

Shame is a social emotion; it can only be healed interpersonally.

If toxic shame tells us we don’t (and will never) belong, then a culture of belonging is one without toxic shame… and one that supports people in processing their healthy shame into guilt and repair and a return to belonging. Matthew Gibson puts it bluntly:

We cannot face our shame alone, certainly not the toxic form of shame that is not ours.

I think there are four steps to supporting transformation, which I want to unpack here.

- Show up with love and compassion: The first step has to do with the motivation and attitude of the supportive partner: if we are sincere about supporting transformation, we must come from a place of love and compassion. Here’s Father Richard Rohr:

What empowers change, what makes you desirous of change is the experience of love. It is that inherent experience of love that becomes the engine of change.

- Practice self-compassion. The purpose of this compassionate witness is to provide a safe environment for them to practice self-compassion. For the vast majority of humans who struggle with self-compassion, the radical act of offering compassion to ourselves is itself the first act of transformation… and those of us who are interested in social change need to support, recognize and celebrate it as such. I credit my wife Jennifer for helping me understand how foundational self-compassion is to the entire enterprise of transformation: it helps us ensure that shame stays healthy and doesn’t turn toxic; it motivates repair instead of paralyzing us into a trauma response. Emily Nagoski is clear on this:

The antidote to shame is self-compassion.

- Feel safe in our bodies: so many of our defenses, particularly around shame, operate at the level of the sub-conscious, and are deeply shamed around trauma. Healing from shame, therefore, is not a cognitive process: it’s somatic. Our bodies need to learn that it is possible to feel safe in the face of shame… to feel at a physical embodied level that there is a path back to belonging. As change agents we can offer the gift of co-regulation: allowing them to experience our own calm nervous systems as an embodied experience of safety. Stephen Porges has a beautiful line here:

If you want to make the world a better place, make people feel safer… the first step is to develop a sense of self compassion in our bodies.

- Practice new behavior. Finally, we need a new strategy to adopt… and it has to be accessible to us. Lisa Lahey had a great two-part interview on Brené Brown’s podcast where she explains:

Motivation is a necessary but insufficient condition to actually change… People won’t make a change unless you find another mechanism to meet the need that the maladaptive behavior is currently serving.

Right. It’s not enough to let go of the old behavior; that is necessary but insufficient. We also need a new behavior to replace it; one capable of meeting the same need. If shame is fundamentally about belonging… this means supporting people in feeling like they belong. Friend and somatic coach Jesse Marshall summarized the research this way, reminding us that this sense of belonging must also be felt in the body:

The body will only let go of the old strategy if it is offered embodied experiences of the safety and efficacy of other strategies.

Mastering shame is a claim to power

Toxic shame is the master’s tool: we must reject it. More: we must work hard to refuse to succumb to it, and to support each other in healing from present and intergenerational trauma and the shame that accompanies it. As Daniel Schmachtenberger notes:

Unhealthy shame has been one of the most powerful tools for systemic control and oppression throughout history.

But healthy shame is one way those with less institutional/structural power can push back: to wield healthy shame skillfully is to exercise power. Jennifer Jacquet contends that shame can be a powerful tool of nonviolent resistance. She explains:

Shame gives the weak greater power.

In researching this piece I found myself returning to the literature (and Buddhist practice) of fierce compassion. The difference between healthy shame and toxic shame (for those of us trying to use shame in service of justice, to challenge entrenched systems of power and oppression) is the target. As Kristin Neff reminds us:

Call out the harm, not the people. Good anger prevents harm; bad anger causes harm.

(I would replace good/bad with healthy/unhealthy, and here anger is the expression of the “fierce” part of compassion that is calling power to account). This is one of our greatest strengths: one I have elsewhere called the righteous anger of hope we feel at injustice. This is to return shame to its pro-social role: as a tool to promote social cohesion in service of the whole, not the narrow interests of those in power (credit to Miki Kashtan for this insight).

One of my favorite contemporary examples that explicitly embraces shame as a tactic is the Swedish-initiated “flying shame” movement. It’s been personally effective in my own life: where even five years ago I wouldn’t have given much thought to air travel and its carbon footprint, now I think about it… and it’s influenced my behavior. I don’t like the sting of shame I feel at the disconnect between my values/beliefs (need to end carbon-intensive industry) and my actions. It’s an example of how a few individuals (including Greta Thunberg) can catalyze individual change by challenging an institutional/systemic practice… by appealing to our own values and exposing our already-existing but not-often-acknowledged dissonance. That feeling of dissonance motivates a reparative impulse. Koshin Paley Ellison explains:

Shame is what we feel when presented with evidence of our own hypocrisy… You’ll never be free until you can feel the pain, feel the sting of the ouch that inspires you to do better.

It also points to a key lesson: we must have alternative ways to meet the underlying need. Flying shame has been far more successful in Europe where there is a well-connected, fast, and reliable rail network… and much less successful in the car and plane-dependent U.S. It’s a fine line to walk: Cathy O’Neil argues that it’s an inappropriate use of shame if it’s not meaningfully possible to change behavior (e.g. shaming rural Americans for using pickup trucks, when they rely on those gas-guzzling vehicles to do heavy work and there aren’t available alternatives). She explains:

The principle is you shouldn’t shame somebody who doesn’t have a choice, and you shouldn’t shame somebody who doesn’t have a voice. If you do one of those things, that’s punching down.

She also cautions us against targeting individuals for systemic problems: the purpose of shame is to transform systems (and yes, the people who make up those systems), to make it easier to live in a world where everyone belongs. Jacquet explains the transformative potential:

Shame’s performance is optimized when people reform their behavior in response to its threat and remain part of the group… Ideally, shaming creates some friction but ultimately heals without leaving a scar.

Co-creating new conditions for belonging

The good news: I think there’s a roadmap to coming into right relationship with shame, to navigating the paradox that kicked off this post. I now feel more grounded: there is a way to show up with love… without letting go of the need for change. I think there is a necessary role for judgment and the skillful wielding of healthy shame: not of people as individuals, but of behavior and systems that are at odds with justice, with the demands of a world where everyone belongs.

Where increasingly I see mindfulness/social justice spaces arguing “stop trying to change people,” I want to offer a more nuanced response. Yes, stop trying to change people… but don’t give up on trying to change behavior. Justice insists that we stay in the struggle, that we continue the difficult work of inviting people—and supporting them—to transform.

The bad news: it’s a tall order. The first step alone may be insurmountable for many of us in the work of social justice: showing up with love and compassion for those whose behavior we wish to transform… is asking a lot. And it reinforces a core truth: we have to show up for ourselves first, and extend the very self-compassion we are inviting others to step into. That is the first act of transformation (I credit this framing to a conversation with Aisha Shillingford).

From that place of self-compassion, we have more agency to transform ourselves and the world. As bell hooks observed in her classic All About Love:

The more we accept ourselves, the better prepared we are to take responsibility in all areas of our lives.

Indeed, this is one definition I like defining the purpose of social change efforts generally, and the invitation to social movements in particular. adrienne maree brown puts it this way:

The invitation to create sanctuary and welcoming movements is to constantly grow people’s responsibility to transform the world for themselves and their people.

We desperately need new norms. Pro-social ways of living and relating that are conducive to a world where everyone belongs. And if we are serious about transformation, this means both co-creating and identifying those news ways of relating… and supporting others (and ourselves!) on the difficult path from here to there. To let go of old norms is to refuse to be shamed by them… to adopt new norms is to feel the sting of shame as we realize we have caused harm.

Of course this all begs an obvious question: how do we decide/agree on these new norms? As friend, collaborator, and parenting expert Jen Lumanlan put it in her in-depth module exploring shame:

If we can’t agree as a society what are the attributes and activities that should be considered shameful, how can we argue in favor of the continued use of shame?

I’ve intentionally sidestepped that question here, because so much of my other writing tackles this question directly (here, e.g.) I wanted to take up shame specifically because so often it is the biggest impediment to the kind of radical imagination I’m longing for. Too often we use it the way it’s been used against us… and it hurts our movements. This post is an invitation to step into right relationship with shame, and therefore to entertain the tantalizing possibility of returning to belonging.

As always, I’d love to hear what lands, what doesn’t, and how you’re making sense of a difficult and fraught topic. I’d love to join you in dialogue around it, in the comments below or in our next subscriber gathering.

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at building belonging

featured image taken by author : “My kids enjoying the bliss of a summer afternoon along a Norwegian fjord“

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here