Creative Freedom for True Equity

Equity is often discussed, but rarely understood in a context that speaks to the core challenges of people who are under-represented in race, religion, gender, socio economic status or who may be geographically excluded and differently abled. In particular, the necessary experiences and spaces for communities within rural Texas are just beginning to receive the attention and resources required to spark conversation and change. Paying homage to deep rooted history and lineage of community members is essential for Black communities in Bastrop County, Texas (and beyond). In Bastrop, home to 13 original Freedom Colonies, the untapped power of equity-for-all lies in the centering of Blackness. In order for our society to evolve, it is imperative to recognize Black America's contributions and sacrifices as a strategy towards equity for everyone. This has been the primary focus of my personal work, which aspires to bring about social change for all.

Grappling with the core roots of exclusion and inequity, Network Weaving helps to build a framework for connection, access, support and consistent learning– a critical necessity for many who have generational ties to this local land. In Central Texas, approaching community organizing from a network weaving paradigm has supported an evolving model of rural mental health equity in many ways by building on existing culture of community-led organizing. By providing resources for gatherings and trainings for local community leaders, network weaving has become a pillar of support for the work already being done by many on-the-ground community members of these rural networks.

As a weaver, the support of this network and the ability to work collectively and autonomously alongside like-minded people has helped me develop the courage to continue down the path of creating safe spaces for Black women and Black boys. While they continue to be challenged by those who rarely experience the feeling of being othered, safe spaces continue to be places where, as Kelsey Gladwell writes, “we can simply be — where we can get off the treadmill of making white people comfortable and finally realize just how tired we are. Valuing and protecting spaces for people of color (PoC) is not just a kind thing that white people can do to help us feel better; supporting these spaces is crucial to the resistance of oppression.”

After the George Floyd Protests, people began coming to us, as community leaders to shoulder the burden of anti racist organizing, but as a mental health clinician, I saw that my community required a more communal approach that centered their mental, spiritual, ancestral and physical health. This led me to co-create a series of social wellness brunches for Black women in central Texas, a podcast about centering community voices in healing, and the Bastrop County Black Boys Collective which aims to nurture their innovation through connection with other boys and men.

Resistance has been the bedrock to creating safe spaces for local black communities, and it has often been misunderstood as an exclusionary act. Finding the courage, self-love and dedication to create from a vulnerable place has been an emancipating experience, making it hard to return back to “business as usual.” My vision and purpose, as I reflect on my life thus far, are to find ways to enhance freedom and liberation for like-minded communities. To get to this creative utopia, I often reflect and ask myself;

- How can I continue to create spaces for renewal, healing, safety, trust and belonging?

- Who understands and can support this desire for creative freedom?

- What are my strategies to unearth the core stories around me that have led to freedom and prosperity for rural Black America?

- How can we as a collective redefine “success” to allow space for our inherent goodness?

- Where and how can I build upon my connections to others dedicated to liberation?

Through my partnership with the network weaving community since 2019, I’ve been able to form lasting relationships to other community organizers, writers, and social change agents who also see a path towards healing for the communities in which they identify. Weavers are a set of individuals looking to bring attention to the causes that they are most passionate about. Working with advocates and activists dedicated to equity initiatives has been confirmation that we have much more work to do but…I am not alone.

As a Black woman, Mother, mental health strategist, and safe space creator, I’ve been able to carve out a path of healing with my community. These experiences have enabled me to have a clear awareness of those around me and the resources needed to build upon a framework of freedom, liberation, reciprocity and resilience while redefining my understanding of self within the totality of my community.

The thought-leaders within the network have remained bold, focused on serving all populations and dedicated to creating a system of social entrepreneurs with the belief that social entrepreneurship which honors the lived-experiences of community leaders and disruptors is the catalyst towards rural social and political change.

We are innovators and creators. My legacy will be the creation of a physical space for healing, freedom, and creativity for the under-represented. As an act of rebellion and love, weaving through my social change work has helped to heal my battle with power by stepping into my potential as a Network Engine, connector and artist. Weaving has become an important aspect of reclaiming my right to connect and create with like-minded individuals. I’ve already begun to witness the shift in our local narrative, relying on the voices, contributions and vast experiences of the black community.

The function, the profoundly serious function, of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, repeatedly, your reason for being. - Toni Morrison

Krystal Grimes, M.S., LPC is the President and Founder of AMMA Empowerment Services, LLC. Krystal is recognized regionally and internationally as a safe space creator and mental health strategist. Through an intrinsic ability and desire to support others, Krystal has positioned herself as a local convener and facilitator for healing and diversity initiatives, supporting the creation of inclusive and brave spaces for dialogue and innovation.

featured image by Alicia W. Brown

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Ceremony: Reyoking the Sacred with Our Social Justice Work

“Disability is an invitation to relationship…It’s that opening that creates the whole ecosystem.”

– Sophie Strand

“Poetry is the language of the apocalypse.”

– Bayo Akomolafe1

As the newest members of turtle island, two-leggeds have always relied on ceremony for connection with, and for instruction from, older forms of sentience and the divine. Ceremonies are an essential part of all cultures across time. It is the absence of such sacred practices that results in disharmony, imbalance, and collective dis-ease. But what ceremonies and by and for whom? As social justice practitioners who come from a broad range of communities, cultures, and traditions, we often have few, if any, shared approaches for bringing together people, place, and spirit. This challenge has only been compounded during the pandemic, which has shifted so much of our work to a video screen.

While there are a number of rituals—often used by social justice practitioners—to help people connect across the virtual landscape, these tend to have more intellectual and emotional dimensions than spiritual. The increasing attention to somatic practices is expanding how we engage with one another in healthy and embodied ways, but our connection to the sacred, to sentience in its myriad of forms, to place—whether it be turtle island as a whole or a particular place on the carapace of her shell—is largely absent in our cross-cultural social change work. And it is this absence of ceremony that is impeding our ability to radically transform, as people and as a complex and interdependent ecosystem as a whole.

Members of the Change Elemental team and many others have written about the importance of inner work, of attending to the interiority of the intervener. But this work is often done separately, as individuals, or in our own spiritual communities, and not centered as much in our collective change efforts. There are exceptions of course, but these only make more stark the general absence of collective practices.

What is needed, what has always been needed, for transformational change, is ceremony—ceremonies in which we reconnect deeply with each other, with great spirit, with all of creation. In God is Red, Vine Deloria, Jr. describes the importance of ceremony for Native peoples. “The task of the tribal religion, if such a religion could be said to have a task, is to determine the proper relationship that the people of the tribe must have with other living things…” As all of creation is sentient—lizards, rocks, trees—then proper relationship is necessary with everything. And how that relationship is learned, celebrated, and restored, is through ceremony.

The healing of injustices and the restoration of aki, of the earth—including all of the creatures who depend on her and on whom she depends—requires restoring indigeneity—that is a deep connection to place, to its sacredness and interdependencies, to cultural sensibilities that are shaped by these.2 This is an individual, collective, and planetary necessity. The restoration of indigeneity requires reconnecting to indigenous practices, whether those practices are indigenous to the Americas, Africa, Asia, or Europe. For those who are not connected or actively reconnecting, this then is your task—and yes, it can be complicated, painful, and messy. It is an extension of inner work, of cultivating the ability to be present to what is and was and then draw on this ability to help create what will be.

And too, when we come together as change makers, we must hybridize and invent new ceremonies to support our current collection of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic beings—all while centering the primacy of the indigenous world in which we are currently walking. It is a potent task, but not without antecedents.

The evolution, resistance, and resilience of indigenous spirituality in the face of settler colonialism and the middle passage provide some clues for how we might accomplish such transgressive divination. And while these adaptations were the result of subjugation and duress, our current times—the extraordinary amount of injustices we are quite literally buried in—necessitate another sacred leap in order for us to work collectively together.

So, how do a diverse group of social justice practitioners develop and practice ceremonies together? One answer can be found in Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer:

I knew that in the long-ago times our people raised their thanks in morning songs, in prayer, and the offering of sacred tobacco. But at that time in our family history, we didn’t have sacred tobacco and we didn’t know the songs—they’d been taken away from my grandfather at the doors of the boarding school. But history moves in a circle and here we were, the next generation, back to the loon-filled lakes of our ancestors, back to canoes…. When I first heard in Oklahoma the sending of thanks to the four directions at the sunrise lodge—the offering in the old language of the sacred tobacco…the language was different but the heart was the same…. It was in the presence of the ancient ceremonies that I understood that our coffee offering was not secondhand, it was ours…. That, I think, is the power of ceremony: it marries the mundane with the sacred. The water turns to wine, the coffee to a prayer. The material and the spiritual mingle like grounds mingled with humus, transformed like steam rising from a mug into the morning mist.3

We find ceremony and we create it together. The languages may be different but the heart is the same. And in that collective mingling, we weave relationships with ourselves and each other, with spirit, and with all other sentient beings.

Learning the grammar of animacy [and here this means recognizing the sentience and aliveness of “things”] … reminds us of the capacity of others as teachers, as holders of knowledge, and as guides. Imagine walking through a richly inhabited world of Birch people, Bear people, Rock people, beings we think of and therefore speak of as persons worthy of our respect, of inclusion in a peopled world….imagine the possibilities. Imagine the access we would have to different perspectives, the things we might see through other eyes, and the wisdom that surrounds us. We don’t have to figure out everything by ourselves: there are intelligences other than our own, and teachers all around us.4

We are living in places flush with sentience. Whether we are working together in person and are able to root into the same soil and arc into the same sky, or we are connecting virtually from across the continent, we can be present to place, to plant and animal teachers, to the places and wisdom of our ancestors, as well as to the divine. In either circumstance, what matters is this presencing of sacred relationship, that we make our interconnectivity the space from which we do our social justice work. Not for reasons of emotional stability or creativity—although it does support both—because the problems we are trying to solve cannot be solved by human beings alone. Both Albert Einstein and Audre Lorde have told us this in different words. Einstein informed us that, “you cannot solve a problem with the same mind that created it.” And Lorde located this understanding alongside its concomitant history when she wrote, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Human beings do not, in isolation, have the ability to solve the problems we have created. A recent example of this can be seen by the effect a simple virus—one of the oldest life forms on the planet—has had on every nation across the globe. The response to this virus has been utterly human-centric, and in the US, utterly middle-class, housed, professionalized worker, and male-centric. And it has been to the peril of every social system, which by their design for and maintenance of inequities then resulted in cataclysmic harm to Black, indigenous, brown, immigrant, female-identified, disabled, refugee, poor—the list is endless—communities across the world. All of creation, whether we look to the big bang or to sky woman falling5, teaches us that we are wildly connected and interdependent, and without our devoted attention to this truth, we will, and do, continue to find ourselves tilting precariously over the edge of a cliff.

The way we presence this connection, the way we center its fundamental truth, is through ceremony. Ceremonies born of our disabilities, our differently-abled abilities, which, as Sophie Strand says, create the opening that enables an entire ecosystem to unfold. This opening too is ceremony. Ceremony is the poetry that languages a new way of being and ways of doing such that the apocalypse can utter its death rattle, be composted, and make way for the regenerative growth of the post-apocalyptic, indigenized, recombinant world in which all of creation can face one another, bow, and begin the dance anew.

1Quotes from their shared talk “New Gods at the End of the World” hosted by Science and Nonduality (SAND)

2“Indigeneity assumes a spiritual interconnectedness between all creations, their right to exist and the value of their contributions to the larger whole.” LaDonna Harris, Founder and President of Americans for Indian Opportunity

3Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants.” Milkweed Editions. Minneapolis, MN. 2013. Pg. 36-38

4 Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants.” Milkweed Editions. Minneapolis, MN. 2013. Pg. 58.

5 There are many written versions of this creation story. One of my favorites is `“You’ll Never Believe What Happened” is Always a Great Way to Start’ by Thomas King from his collection The Truth About Stories, House of Anansi Press, Inc. Toronto, Ontario. 2003.

Aja Couchois Duncan (she/her/we) is a San Francisco Bay Area-based leadership coach, organizational capacity builder, and learning and strategy consultant of Ojibwe, French, and Scottish descent. A Senior Consultant with Change Elemental, Aja has worked for 20 years in the areas of leadership, equity, and learning.

Header image credit: Taylor Wright

Originally published at Change Elemental

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Reclaiming Care Beyond Roe v. Wade

When the state cannot guarantee our safety, we turn to community as our ancestors did

On June 24, Roe v. Wade was overturned by the Supreme Court after nearly 50 years as precedent.

Weeks before, in response to the leaked decision, Resonance Network hosted ‘We Are Our Own Medicine,’ a gathering grounded in community, storytelling, and ancestral wisdom. Alongside Black and Indigenous healers of various traditions, we came together knowing what our ancestors have known for generations: the state cannot guarantee our safety — it never has.

In the US, incarcerated, disabled, undocumented, poor, queer and trans folks, and survivors have been denied reproductive rights, bodily autonomy, and care for decades. Because this violence lives in our history — and shared reality — we gathered to learn from and share stories from ancestors — past and present — who’ve lived this experience.

In short, when the state cannot guarantee our safety, we turn to community as our ancestors did.

Below is a constellation of wisdom from ‘We Are Our Own Medicine.’

* * *

Deoné Newell — Women’s Empowerment Coach

Deoné is a Navajo/Black entrepreneur, Breathwork Facilitator and Women’s Life Coach. As a woman who hails from the Navajo Reservation (Window Rock, AZ), and has seen the effects of systemic oppression and generational trauma firsthand, Deoné has dedicated herself to making ancestral healing, and its forgotten wisdom accessible to as many BIPOC women as possible.

Karen Culpepper—Clinical Herbalist/Educator

Karen has been a practitioner and bodyworker for over 14 years, focusing her work on intergenerational trauma and its impact on physiology and womb restoration. Her study of cotton root bark as an abortifacient and source of sovereignty for descendants of captured Africans in the US and beyond offers insight into the role of plant spirit healing in the context of political changes.

Qiddist Ashé—Founder, The Womb Room

Qiddist is a medicine woman and female health educator. Informed by her maternal lineage of Ethiopian midwives and her own work in authentic midwifery, functional health, herbalism, somatics, and spiritual sovereignty, Qiddist merges the science and the spirit of female health, orienting to all the ways we can reclaim agency and responsibility for our bodies and our lives.

Camila Barrera Salcedo—Doula/Midwife/Educator

Camila is a mother of 3, doula, midwife, sexuality therapist, and holotropic breathing and fertility therapist. She delves into the unconscious via the physical body to identify blocks that disrupt the evolution and transformation of individuals. She develops workshops to re-establish the feminine consciousness through acceptance and knowledge about the body and its processes.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

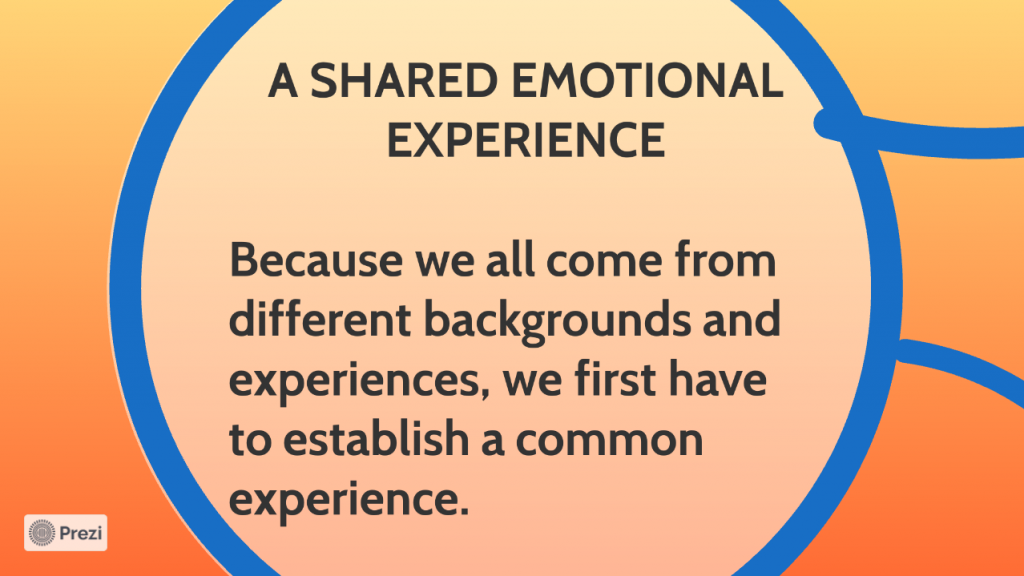

From Learning to Doing

Many years ago I was teaching high school English on a small island in SE Alaska. I asked the class to compare a piece of literature to the story of the Three Little Pigs. Half of the class couldn't do the assignment because they had never heard of the story of the Three Little Pigs. That changed me forever.

Without shared experiences, learning communities often talk past each other. Inevitably there is a judgement on one side or the other. Each learner brings his/her own experiences to a conversation and uses those unique experiences to make sense of things. Coming together as a learning community to sort through what we understood from something new that is introduced to us is sometimes very frustrating because of all the different experiences brought to the table. To help with that issue in almost any learning community, you can initiate a common experience/action for all participants. When an action is experienced together, suddenly there is more justice in the conversation. The playing field is leveled and the real conversation can begin.

This is a depiction of how that process can be set up for any learning community. The condition is that the learning spiral never ends....every round goes higher, higher. The outcome is that participants almost always feel like they can act on their new knowledge and continue the learning cycle on their own.

Click HERE to access the "From Learning to Doing" resource. A slide presentation on how to create shared experience in a community to initiate actionable change.

Click HERE to access the slide show directly at prezi.com

Cindee Karns, a life-long Alaskan, is a retired middle school teacher with a master's in Experiential Learning. She is founder/weaver of the Anchor Gardens Network, which is attempting to bring increased food security to Anchorage. She and her husband live in and steward Alaska's only Bioshelter

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

The illusion of hopelessness

The war in Ukraine is a symptom of something bigger— and within reach

In times of war, we are led to believe we are powerless.

We are told that violence is inevitable, an unfortunate part of the way things are. And that the way things are cannot change.

As world events have transpired over the last two weeks, this illusion has begun to splinter

* * *

Russian military forces invaded a sovereign nation on February 24th. Within days, the United States, the European Union, and other nations announced a series of economic sanctions on Russia. At the same time, countries of the European Union waived visa rules for Ukrainian refugees–allowing those fleeing war to enter the EU without having to seek asylum.

Homes across Europe have opened their doors to Ukrainians fleeing war, and President Biden announced that Ukrainian refugees would be welcome in the US “with open arms.”

These moves were swift and unprecedented. Rules that had long existed were replaced with new ones. Systems changed as people and countries moved together in response to a humanitarian crisis.

How quickly rules can change when we want them to.

How malleable systems can be when we agree on what is right.

* * *

Russia’s attack on Ukraine, like all wars, is a symptom of a worldview of domination and extraction.

Like all wars, it exists amid other symptoms and consequences of this worldview: modern dependence on oil and the interests of the fossil fuel industry; unmistakable racism at the Ukrainian border as Africans were systematically turned away.

And the global coordination to condemn Russia’s attack and support the Ukrainian people was made possible, in part, by white supremacy: Western sensibilities were stirred by seeing white refugees. Meanwhile, escalating humanitarian crises in Afghanistan, Palestine, Yemen, Syria, Somalia, and Ethiopia have not been met with the same swiftness.

Imagine a world where all people in need were met with dignity and humanity. Where violence and harm was met with resounding care.

Imagine systems of governance that hold these values above all others.

* * *

In times of war, we are led to believe we are powerless by those who benefit from our silence. We are led to believe our collective systems cannot change by those who benefit from the way things are. Meanwhile, worldviews of domination and extraction continue to shape our reality and perpetuate harm.

As the war in Ukraine has unfolded, we’ve also seen a wave of dehumanizing legislation against queer and trans young people, increasing threats to reproductive justice, and an alarming epidemic of homelessness continuing in the US, all while COVID cases spike in Europe and Asia.

When we understand that all violence is a symptom with the same cause, we can also see that we are not just spectators to what is happening — in Ukraine or right beside us.

There is hope, and the hope is us.

* * *

“There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation.

The challenge is in the moment; the time is always now.”

~James Baldwin

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Originally published 3.16.22 at Reverb