Strengthening Social Connection and Opportunities in Rural Communities

This brief describes an unfolding learning journey intended to strengthen social connection, resident voice, and agency to address inequities in rural health and well-being. Along the way, we have come to realize the important lessons for each of our institutions and ways in which we are better off for having taken this approach to our work.

At St. David’s Foundation, we believe that realizing health equity to minimize the consequences of poverty and racism reflected in the social determinants of health is foundational in our work in Central Texas. Rural communities are dramatically under-represented in philanthropic investments nationwide and in Texas, and the Foundation’s own balance of investments skews toward initiatives that serve urban populations. When philanthropic dollars are invested in rural communities, they are typically directed to the few established nonprofits and local government entities that implement programs or provide services to residents. Community members, especially people experiencing vulnerability and isolation, are rarely asked what they need to improve their health and quality of life and how they may utilize the power inherent in their communities to contribute to those improvements. The most common observation from the philanthropic sector is that “these residents” are rarely poised to receive and control funds to work on the issues they believe are most important for the health and well-being of their own community. Listening and enabling capacity can change that.

Listening to our Rural Neighbors

After a sustained period of building deeper ties and stronger relationships in our rural communities surrounding Austin and Travis County, the Foundation learned that many of our rural neighbors felt disconnected from and ignored by the Foundation and local decisionmakers in their communities who decide how resources are prioritized and distributed to address community needs. Residents from the surrounding rural counties of Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays, and eastern Williamson County expressed an interest in working with the Foundation and their peers on priority concerns including youth, mental health and substance use and misuse, food insecurity, and affordable housing.

Community Capacity Building and Enabling as Rural Strategy

In partnership with The Strategy Group (TSG), a national consulting firm with expertise in catalyzing resident-led community networks focused on health and well-being, the Foundation invested in community capacity building (CCB) strategies to engage interested residents in working collaboratively on issues of importance to community members and enable their inherent power to participate in problem solving.

Informed by residents, the Foundation and TSG co-designed an approach that incorporated key community capacity building outcomes so that residents could develop their own solutions to pressing self-identified community health concerns. TSG also offered a process for the Foundation to build its own capacity to invest differently in rural communities— an approach that invested in network infrastructure, resident leadership development, nonprofit leadership to partner with and support community networks, and connected people experiencing vulnerability and lack of connection to opportunities for community development.

The Foundation’s rural strategy centered social impact networks (Plastrik et al 2014), network weaving (Holley 2012), and sustained community engagement to create an expanding, diverse, inclusive resident-led network focused on health and wellbeing -inequities often reinforced by historical and structural legacies of exclusion and privilege. Stuart (2014) notes, “this is one of those cases where a commitment to social justice is crucial. It is important to consider who is included in the “community” that is leading the process. Who is excluded from community leadership? Whose voices are missing from community debate? Whose interests are being served?”

And if the community is driving decisions about their own development, what does that mean for how the Foundation should be investing in community?

Centering Equity and Equitable Opportunity

As St. David’s Foundation has embraced and prioritized health equity, rural investments evolved to become more place-based and community-focused. How the Foundation showed up in the community (and how frequently), how grant opportunities were presented, and how funds were distributed when CCB was the overarching purpose changed the nature of the relationship between funder and community. In our rural work, the Foundation recognized that a portion of our rural investment needed to give the community control over decisions and resources to determine what resources were needed to spur or make lasting change.

Bringing it all Together in Central Texas

The community network approach in Central Texas prioritizes:

- Centering the voices and lived experiences of rural BIPOC residents (equitable opportunity);

- Seeding a network of interested resident leaders who have a deep understanding of their and their neighbors’ needs to direct their own community development work; creating new relationships; and offering new ways of working, thinking and leading in community; (i.e., social impact networks);

- Engaging and supporting local residents to organize themselves to work on projects that move the community from talking about problems to taking action on problems (i.e., self-organizing);

- Supporting residents who want to develop the leadership skills to engage other residents to work together in a resident-led network focused on health and wellbeing (i.e., network weavers); and

- Putting a pool of resources into the hands of those who have the lived experiences of health inequity, poverty, social isolation; are closest to community problems; and who want to work with their peers to improve community health and wellbeing from a solidarity stance.

What are Networks and Network Weavers?

Social impact networks (like the ones emerging in Central Texas) are constellations of people, organizations, and communities connected by a shared purpose to make change. In the Central Texas network, there is a high-level purpose to improve the health and wellbeing of residents in the region.

Network weavers are residents in the Foundation’s rural service area who have chosen to be a leader in the network; they are the “engines” of our regional network. Weavers strategically connect other residents, convene groups of interested residents, coordinate small projects aligned with resident interests and needs, and work to grow the network and the projects the network is interested in pursuing. Holley (2012) describes a network weaver as “someone who is aware of the networks around them and explicitly works to make them healthier. Network weavers do this by helping people identify their interests and challenges, connecting people strategically where there’s potential for mutual benefit, and serving as a catalyst for self-organizing groups.”

The Foundation provides operating support for TSG as well as funds to support network infrastructure (e.g., communications, evaluation, training, storytelling), stipends for weaver leaders, and shared gifting circles. To date, over 100 residents have been trained to be network weavers in Central Texas.

Building Community Leadership

The Foundation’s investment in community capacity building by catalyzing resident-led networks and training residents to become network weavers is designed to engage and support residents to contribute their time and talents (i.e., community leadership) to solve pressing self-determined health and wellbeing challenges in their own communities. Residents also participate in monthly peer assist sessions which enable real-time feedback and advice from peers as they practice their leadership skills.

Participatory Grantmaking

Using participatory grantmaking processes and resources, network weavers are supported to identify local problems and then work collaboratively with other residents to co-design and test solutions. Shared gifting emerged as an important participatory grantmaking tool to support weavers during the second year of project implementation. We asked ourselves: “how can a small pool of grant funds be used to foster connection across different communities and authentic collaboration, rather than competition?” Shared gifting allows residents to decide what the most urgent community needs are, rather than the Foundation, and then to grant dollars to community projects they wish to support. There are no required outcomes of the process other than what is determined by the participants during the shared gifting process.

From participant reports of the shared gifting process, we were excited to learn that a shift in control of grant funds from the Foundation to the group of network weavers (residents) created an environment of social connection, equity, encouragement and support, feelings of abundance, and community. The typical grantmaking experience of competition and scarcity often experienced by potential grantees when responding to competitive grant opportunities was not reported by participants. Instead, weavers were excited to make new connections with other weavers, hear about new projects happening in their community, extend offers of time, talent, and treasure to other weavers, and expressed pride to be able to support those projects with the resources they controlled.

Conclusion

Residents who have participated in network weaving and participatory grantmaking have shared a common experience of personal and professional transformation, social connection, empowerment, and awareness of new possibilities and promise for their communities. The Foundation’s experience of investing in rural communities and its people by creating opportunities for resident decision making about how resources should be directed to pressing issues in their communities has revealed new possibilities for grantmaking and use of our social capital to advance the health and wellbeing of rural residents in Central Texas. Further, the experience with weavers as grantmakers underscores the importance and urgency of integrating community voice consistently in the Foundation’s equity-driven journey.

Voices and Learnings

Network weavers were invited to share their thoughts on how weaving has influenced their personal and professional lives. The themes found in their comments were that network weaving:

- Offers both professional and personal value to persons.

- Provides a framework that is valuable to tackle complex community issues.

- Facilitates making connections that create change in the community.

- Allows the use of shared gifting as a unique learning, connecting, and growing experience.

- Fosters among network weavers a desire to build new skills and capacities to continue to strengthen their work within their own communities.

- Encourages persons who had existing networks to make those networks more effective, efficient, and stronger by implementing what they learned in the Network Weaving learning opportunity.

“Weaving has tremendous value as it has empowered me to create with others outside of my usual network, helping to expand my reach and capacity to support others.“

“Throughout the past few years, in a mid-COVID society, Network Weaving has proven to be a skill set and collective necessity to maintain community collaboration. As work-life has evolved and more individuals experience isolation, Network Weaving has made the ability to connect (in-person or virtual) a go-to process for me in my personal and work life.“

Krystal Grimes, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Ultimately, all of us have the same end goal of building a better community. We all are here for the same reason; we’re all doing this work because we have a passion for community building. And network weaving has really given us that opportunity.”

“It has given me a really clear framework for what I’m doing. It’s not something that lives in my brain. Now. it’s an actual process and an actual framework that I can utilize to share information.”

Elizabeth Marzec, 2021, Organizational Leader, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Helping the community that you live in, helps you, it helps your children and helps your grandchildren. So, I think that is the point in the future that weaving really impacts.”

Linda Quiroz, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Bringing leaders together, making community change, and having people who never thought of themselves as a leader know that they can all make a difference. I love that.”

Kathleen Moore, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Prior to network weaving, I had no idea how to get this passion, this idea realized . . . I’m trying to be involved in the community. But I needed direction. I needed ideas, I needed strategies. And so, when I was invited [to learn about network weaving], it gave me what really felt like a breath of fresh air, because I’m going to be around peers that can help me along the way. And then also for me to help others.”

Sonya Hosey, 2021, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“I think about the word power. And that power is shared. It doesn’t belong to one person or group . . . and I love that about network weaving,”

“I have watched the whole design of network weaving just open this road for people to speak and share and dream, and nothing is impossible”

Maureen Stanek, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

References

Holley, J. (2012). Network weaver handbook: A guide to transformational networks. Athens, OH: Network Weaving Publishing.

Moore, W. P., Klem, A.M., Holmes, C.L., Holley, J. and Houchen, C. (2016). Community innovation network framework: A model for reshaping community identity, The Foundation Review, 8(3). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1311.

Plastrik, P., Taylor, M., and Cleveland, J. (2014). Connecting to change the world: Harnessing the power of networks for social impact. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Stuart, G. (Apr 10, 2014). What is Community Capacity Building? Impact Initiative.

Abena Asante has over twenty years’ experience in philanthropy, public health, and the nonprofit sector. A senior program officer at St David’s Foundation, she leads efforts that catalyze community action around issues and opportunities that align with the Foundation’s firm commitment to achieve health equity.

Dr. William Moore is Principal at The Strategy Group, a Kansas City-based international consulting firm supporting nonprofits, foundations, and communities. Bill is a Senior Fellow at the Midwest Center for Nonprofit Leadership at the University of Missouri – Kansas City, Senior Associate for Rural Health at the Texas Health Institute, and is the rural health advisor to the St. David’s Foundation.

originally published at gih.org

A in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and studied at Sciences Po, Paris as an Erasmus scholar.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Community engagement: How to create meaningful connections in an age of distrust

Community engagement is a term applied in various contexts, often meaning different things to different audiences. It is sometimes used interchangeably with other concepts such as community outreach or community consultation. For the purpose of this article, we utilise the term community engagement to describe a process where local government, charities, and funders collaborate meaningfully with the communities that they serve.

The insights presented in the following text are informed by our experiences working with the above groups. We hope this article is particularly useful to those who are hoping to build stronger and better-informed relationships with their communities.

Community engagement

Community engagement is a key part of any project or programme that seeks to directly enhance the lives of the public. When providing services that affect people belonging to a defined area or group, building relationships within that community is a non-negotiable. Whether you’re a charity, funder or government authority, understanding what communities are thinking and feeling, and taking those thoughts and feelings seriously, is the only road to a legitimate and meaningful partnership.

What is community engagement?

Why is community engagement important?

How should I approach community engagement?

Download The Community Engagement Canvas [Free Resource]

What is community engagement?

Community engagement is all about supporting communities to take ownership of the resources that are available to them. This means taking an active role in creating partnerships between the institution that is providing those resources, such as a local council or charity, and the communities that will be receiving them. Grassroots, voluntary and faith organisations as well as mutual aid groups are deeply embedded in their communities and have a great understanding of local dynamics. This is what makes them such important partners for service providers.

In the simplest sense, community engagement is likely to involve connecting with community leaders and facilitating conversations about what they would like to see happen in their communities. This might look like restoring public spaces such as libraries or a community garden, engaging in discussions around improving housing standards or planning and programming a community event.

Why is community engagement important?

Over the last two decades, trust in ‘big’ institutions has been in a state of flux. Historical events such as Brexit and more recently COVID-19 have shifted our understanding of public life and how we relate to the institutions and organisations that shape it. The latest British Social Attitudes Survey reported that only 23% of people trust the government to put the needs of the nation before the interests of their party. So, how can those with institutional power begin to build back trust with the communities that they serve?

An approach gathering momentum in the US termed ‘earned legitimacy‘ puts forward the argument that it is the role of public institutions to build bridges with communities who have lost faith in their ability to serve. More specifically, it suggests that a public institutions’ legitimacy hangs directly on how much their community trusts them to act justly on their behalf.

Government might be a useful example to illustrate the meaning of earned legitimacy, but we believe that this approach is a solid one for any organisation that has the power, resource and will to engage communities in their activities. In short, it’s on you to put the work in.

How should I approach community engagement?

1. Get real about the role of history

When you work for a long-established organisation with substantial control over wealth and resource, people are likely to have pre-existing ideas about what you do and how you do it. Historically, many communities have been underserved and even harmed by powerful institutions. We see examples of this frequently in the news, whether it’s black individuals being more likely to be subject to stop and search or international charities such as Oxfam’s failure in preventing abuses of power. It makes sense that some communities are sceptical to work with those that have represented racism, mistreatment and harm to them in the past.

‘What are your concerns about this organisation and is there anything we can do to reassure you?’

The Centre for Public Impact recently released a report on how they went about restoring trust between Americans and local government by working with local communities in four different parts of the US. This involved “acknowledging past wrongs and showing a commitment to confront[ing] present-day […] issues.” The report highlights how important it is for historical tensions to be addressed with openness and honesty, especially in the early stages of relationship-building. This may involve asking community members questions such as ‘How do you feel about working with us?’ or ‘What are your concerns about this organisation and is there anything we can do to reassure you?’ before embarking on a shared venture.

2. Recognise that expertise exists within communities

The starting point for community engagement should almost always be that nobody understands what a community wants and needs better than the people belonging to the defined group. Big institutions often work with experts and consultants to problem solve and generate solutions. The Social Change Agency believe that the answers exist within communities and it’s really about creating safe spaces where those insights can be shared. If you are engaging communities in a consultation process, it’s worth considering that individuals should be paid for their time. They’re the real experts.

3. Getting to know each other is work too

With deadlines, budget restraints and the pressure to demonstrate outcomes, we often want to skip small talk and get right to the finished product. If you have the power to write ‘getting to know each other’ time into your project plan, this could really support relationship-building with your community and will almost definitely make things more efficient in the long run. Taking the time to visit the people you’re hoping to engage with and really understanding what motivates them can help to create the conditions for a durable partnership.

4. Communication, communication, communication

Whether it’s email, Slack, WhatsApp or Facebook, the way we interact often shifts depending on audience and urgency. This is no different when we are engaging with community networks. If barriers to communication emerge, it can drastically affect your relationship and slow down the pace of delivery. At the very beginning of your community engagement endeavour, ask community members how they would like to be contacted and what is most convenient for them. Make it as easy as possible to connect but create boundaries around how often and when is appropriate to communicate. This will give you a solid vehicle via which collaboration can flourish.

5. Defining success together

What success looks like to communities and what success looks like to funders, governments and charities are often two entirely things. Success to a local authority might be engaging 20 different community groups in a consultation process before opening a new digital community hub. Community members may visualise success as guaranteeing this space is free to use for certain age groups.

A way of define shared success might be creating an accessible and affordable digital hub designed by and for the community. It’s worth having a conversation about what both of your ambitions are for working together and creating a sense of shared purpose in your collaboration. Establishing a common goal is likely to keep you connected as you move through the logistics of delivery.

originally published at Social Change Agency

Maisie Palmer 's interests lie in social innovation, education, and supporting community-led movements. Prior to joining our consultancy team, she was National Programme Lead for Education at The Roots Programme where she designed and delivered an exchange programme tackling social division amongst British youth. Maisie founded Mxogyny an online and print publication for marginalised creatives. She has also worked for the Secretary of State for Scotland and the International Criminal Court. Maisie holds an MA in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and studied at Sciences Po, Paris as an Erasmus scholar.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Reclaiming Care Beyond Roe v. Wade

When the state cannot guarantee our safety, we turn to community as our ancestors did

On June 24, Roe v. Wade was overturned by the Supreme Court after nearly 50 years as precedent.

Weeks before, in response to the leaked decision, Resonance Network hosted ‘We Are Our Own Medicine,’ a gathering grounded in community, storytelling, and ancestral wisdom. Alongside Black and Indigenous healers of various traditions, we came together knowing what our ancestors have known for generations: the state cannot guarantee our safety — it never has.

In the US, incarcerated, disabled, undocumented, poor, queer and trans folks, and survivors have been denied reproductive rights, bodily autonomy, and care for decades. Because this violence lives in our history — and shared reality — we gathered to learn from and share stories from ancestors — past and present — who’ve lived this experience.

In short, when the state cannot guarantee our safety, we turn to community as our ancestors did.

Below is a constellation of wisdom from ‘We Are Our Own Medicine.’

* * *

Deoné Newell — Women’s Empowerment Coach

Deoné is a Navajo/Black entrepreneur, Breathwork Facilitator and Women’s Life Coach. As a woman who hails from the Navajo Reservation (Window Rock, AZ), and has seen the effects of systemic oppression and generational trauma firsthand, Deoné has dedicated herself to making ancestral healing, and its forgotten wisdom accessible to as many BIPOC women as possible.

Karen Culpepper—Clinical Herbalist/Educator

Karen has been a practitioner and bodyworker for over 14 years, focusing her work on intergenerational trauma and its impact on physiology and womb restoration. Her study of cotton root bark as an abortifacient and source of sovereignty for descendants of captured Africans in the US and beyond offers insight into the role of plant spirit healing in the context of political changes.

Qiddist Ashé—Founder, The Womb Room

Qiddist is a medicine woman and female health educator. Informed by her maternal lineage of Ethiopian midwives and her own work in authentic midwifery, functional health, herbalism, somatics, and spiritual sovereignty, Qiddist merges the science and the spirit of female health, orienting to all the ways we can reclaim agency and responsibility for our bodies and our lives.

Camila Barrera Salcedo—Doula/Midwife/Educator

Camila is a mother of 3, doula, midwife, sexuality therapist, and holotropic breathing and fertility therapist. She delves into the unconscious via the physical body to identify blocks that disrupt the evolution and transformation of individuals. She develops workshops to re-establish the feminine consciousness through acceptance and knowledge about the body and its processes.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

What do we mean by “community”?

Since the inception of Building Belonging, we’ve wrestled internally with this question: what are we? On our homepage we say we are:

A home for people committed to building a world where everyone belongs… We are a community of people working toward transformation and liberation: of ourselves, our societies, and the world.

And yet our gathering place is on Mighty Networks; so clearly we see ourselves at some level as a network as well.

So we’re a home. And a community. And a network. What does that mean, exactly? How do we organize ourselves? How do we make decisions? And as money flows through the system and we face the legal/financial imperative to adopt a structure… are we also an organization?

I don’t want to speak for Building Belonging here; we are in the middle of our second interim Stewardship Process, precisely to take a collective perspective on questions like this. But I did want to share my own intentions in case it’s helpful to others wrestling with these questions in their own communities/networks/organizations; I see this question as a key point of differentiation in the social change ecosystem that feels important to name.

1. I am interested in building a community, not an organization. I love this definition from

Aaron Goggans and team at Wildseed Society (which I see as a kindred initiative to BB):

We define community as a group of people with such important or valuable interrelationships that it is easier to have the difficult conversations than walk away. It’s a space where we agree to labor together to root out domination from our praxis and replace it with more liberatory ways of meeting our needs.

2. The kind of community I’m interested in co-creating is synonymous with the concept of “political home.” That is, it must contain two components. A “home”: a space of nourishment, resilience, support, safety, deep commitment to each other, and comfort. And it must also be “political,” meaning we are gathering in order to transform: ourselves, each other, and the world. It’s a space of stretch, of intentionally pushing ourselves to change material conditions in our community (as a fractal) and in the world.

There are other communities that are only or primarily about “home,” and communities that are only or primarily about “political.” Building Belonging — for me — is an effort to co-create a political home. Both things are essential. I resonate with how adrienne maree brown describes it:

Political home…is a place where we ideate, practice and build futures we believe in, finding alignment with those we are in accountable relationships with, and growing that alignment through organizing and education.

Yes! This is what I mean when I talk about Building Belonging as a “future dojo”: it’s a place to practice in the present… the future we long for. It’s prefigurative.

3. Communities require shared cultural norms. Absent direct deep relationships among all the members (which becomes impossible with growth beyond a certain point), structure is what codifies those norms: structure provides guidance on how we “be” together. It is the walls and furniture and doors that help people know how to navigate the community, where to sit, how we cook and clean together, etc. This is the space around “liberatory governance” that I find so compelling. And if we want to have any hope of co-creating the self-organizing future we long for… liberating structures are essential.

4. Communities require active leadership (I prefer the term stewardship). I love

Vanessa C. Mason’s reflections here:

Communities don’t just happen. They are intentionally built and stewarded by official and unofficial community weavers.

Yes: weavers inside and across communities. This echoes the core insights that

Fabian Pfortmüller has so beautifully captured in his work. Which means we will need people (in dynamic roles!) who are taking responsibility for stewardship. If we see Building Belonging as a commons, a fractal of the whole, than stewarding the commons is both a collective/universal responsibility, and a specific defined responsibility.

We aspire to self-organization, but it’s a long way from here to there. Humans aren’t yet a murmuration of starlings; we have to remember those skills, cultivate the capacity that’s been stolen from us. Until then, we depend on the contributions of stewards to create the conditions for everyone to step fully into community.

Alanna Irving is blunt on this point. She says:

There’s no such thing as self-organization. There’s only unseen, unacknowledged, and unaccountable leadership.

I love Parker Palmer’s 13 ways of looking at community (hat tip to Building Belonging member Sara Huang for pointing me to them):

Community requires leadership, and it requires more leadership, not less, than bureaucracies.

5. The kind of communities I’m interested in are also networks: people connected in diverse ways around a shared purpose. In this I’m drawn to the insights emerging from the network weaving community around how we cultivate connections;

David Ehrlichman’s new book on Impact Networks is a great overview of the field.

6. Community is a place to share gifts and needs; to thrive, everyone has to contribute. We all make community real in different ways. My gift might be for synthesis, for distilling and naming patterns amid complexity. Someone else’s gift might be holding space for conflict or big emotions; someone else might have a gift for art, music, or film: these are all equally welcome. Part of my hope for Building Belonging is to be able to create the conditions (norms, structures, culture, ways of relating) to enable people to step fully into their gifts; we aren’t there yet. I love

Deepa Iyer’s work here naming different roles in social change.

7. Community is the only sustainable form of support. I love this line from Esther Perel, commenting on this global moment of polycrisis and accelerated change, when our dominant systems are collapsing and we find ourselves unmoored:

Community is the only thing we have at this point… real life embodied experiences where people come together.

I’ve been thinking about this provocative line from Tyson Yunkaporta:

The only sustainable way to store [information] long term is within relationships.

I might expand that sentiment: it’s the only sustainable way to do anything. Buildings will crumble; the power grid will fail; the supply chain will break. The only thing we have to turn to, reliably… is each other.

Anyway, obviously lots more to say here, but wanted to put out some initial thoughts. I’d love to hear what resonates for others, what doesn’t, and how you’re making sense of this in your own lives and work.

In community (political home :-),

Brian

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at medium.com

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Into the Matrix and Beyond: The Value of Network Values and Values-Focused Processes

A couple of years after the Food Solutions New England Network officially published the New England Food Vision, and just after the network formally committed to working for racial equity in the food system, it formally adopted a set of four core values. On the FSNE website, a preamble reads: “We collectively believe that the food system we are trying to create must include substantial progress in all these areas, alongside increasing the consumption of regionally produced foods and strengthening our regional food economy and culture.” The four values are:

Democratic Empowerment:

We celebrate and value the political power of the people. A just food system depends on the active participation of all people in New England.

Racial Equity and Dignity for All:

We believe that racism must be undone in order to achieve an equitable food system. Fairness, inclusiveness, and solidarity must guide our food future.

Sustainability:

We know that our food system is interconnected with the health of our environment, our democracy, our economy, and our culture. Sustainability commits us to ensure well-being for people and the landscapes and communities in which we are all embedded and rely upon for the future of life on our planet.

Trust:

We consider trust to be the lifeblood of collaboration and collaboration as the key to our long-term success. We are committed to building connections and trust across diverse people, organizations, networks, and communities to support a thriving food system that works for everyone.

In the last few years, these values have generated a lot of good discussion, both internal to the network and with others, and we are discovering that this really is the point and advantage of having values in the first place. They can certainly serve as a guide for certain decisions, and in some (many?) instances things may not be entirely clear, at least at first. What does racial equity actually look like? Is it possible for a white-led, or white dominant, institution to embody racial equity? Can hierarchical organizations be democratic? Are there thresholds of trust such that people are willing to not be a part of certain decisions in the name of moving things forward when needed?

Recently, FSNE received an email from a Network Leadership Institute alum who now works as a commodity buyer for a wholesale produce distributor in one of the New England states. They reached out to inquire who else in the network might be thinking about high tech greenhouse vegetable production in the region. Specifically their interest was talking about projects that use optics of being “community based,” but are financed by big multinational corporations. “What would a “just transition” framework look like in the context of indoor agriculture,” they wondered, especially in light of undisclosed tax deals happening as the industry rapidly grows.

As it turns out, a public radio editor recently reached out to FSNE Communications Director, Lisa Fernandes, about pretty much the same thing, also referencing other similar projects taking root in different parts of the region. What does FSNE think of these? Part of her response was that there are some good questions that not only the New England Food Vision (currently being updated), but also the Values, can raise to evaluate the potential role of some of these more tech-heavy food system projects and enterprises as the region strives to be more self sufficient in its food production. And this conversation is certainly growing.

These exchanges in our region have had me thinking about work colleagues and I have been doing with food justice advocates in Mississippi. A central part of this also lifts up values as being key to establishing “right relationships” between actors in the food system, and also between advocates and partners (including funders) from outside of the state. I have learned much from Noel Didla (from the Center for Ideas, Equity, and Transformative Change) and her colleagues about the importance of establishing what they call “cultural contracts,” which create a foundation of values-based agreements as a way of exploring possibilities for authentic collaboration. The signing of any contract is just a part of a process of ongoing dialogue and trust building. For more on these contracts and culture building, see the recording of a conversation Karen Spiller and I had with Noel and other Mississippi food system advocates during the FSNE Winter Series earlier this year in a session called “The Power of the Network.”

“Daring leaders who live into their values are never silent about hard things.”

Brene Brown

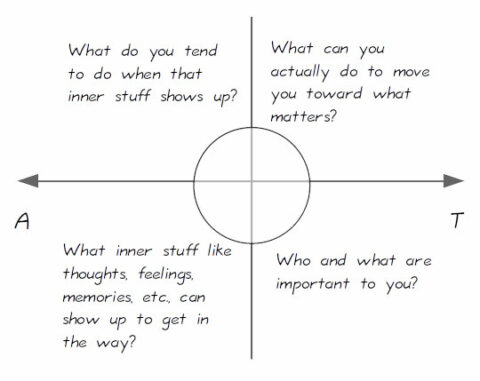

In a different series of workshops with those same Mississippi-based advocates, we introduced a values-focused tool from the PROSOCIAL community. PROSOCIAL is rooted in extensive field research (including the commons-focused work of Nobel Prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom) and evolutionary and contextual behavioral science. PROSOCIAL offers tools and processes to support groups in cultivating collaborative skillfulness and the critical capacity of psychological flexibility, including the application of Acceptance and Commitment Training/Therapy (ACT) techniques.

The ACT Matrix (see below) is something that individuals and groups can use to name what matters most to them (their core values), along with aligned behaviors (what are examples of living out these values?), as a way of laying a foundation for clarity, transparency, agreement, support and accountability. The Matrix also helps people to name and work with resistance found in challenging thoughts and emotions that might move them away from their shared values. The upper left quadrant is a place to explore what behaviors might be showing up that move people away from their stated values. In essence, this helps to both name and normalize resistance and when used with other ACT practices (defusion, acceptance, presence, self-awareness), can encourage more sustainable, fulfilling (over the long-term), and mutually supportive choices.

An additional values-based tool we have lifted up both in New England and in our work in Mississippi is Whole Measures. Whole Measures is a participatory process/planning and measurement framework from the Center for Whole Communities). There is both a generic version of this framework, as well as one specifically focused on community food systems (more information available here). As CWC points out, “How the tool or rubric framework is used, how the community engagement is facilitated, who is represented in the design matters.” Whole Measures is about content, yes, and it is meant to be used for ongoing deep dialogue, especially amidst complexity, diversity and uncertainty, and when faced with the challenge of tracking what matters most that can also be difficult to measure.

When it comes down to it, these times seem be asking us what kind of people we really are and strive to be. As the old saying goes, “If you don’t know what you stand for, you’ll fall for anything.” And so the work of values identification and actualization is of paramount importance. I’ll leave it to the poet William Stafford to appropriately close this post with his poem, “A Ritual to Read to Each Other” (something we often share with social change networks as we launch, especially the first and last stanzas):

If you don’t know the kind of person I am

and I don’t know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the world

and following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,

a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break

sending with shouts the horrible errors of childhood

storming out to play through the broken dike.

And as elephants parade holding each elephant’s tail,

but if one wanders the circus won’t find the park,

I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty

to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.

And so I appeal to a voice, to something shadowy,

a remote important region in all who talk:

though we could fool each other, we should consider—

lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark.

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate at the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC). Much of his work entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food, education, public health, and economic systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

featured image found here