EXPLORING THE COLLABORATION CYCLE

Below is an excerpt from the full article which can be downloaded here or at the bottom of this post. This article a part of the Tamarack Institutes Collaborative Governance and Leadership series.

The Collaborative Context

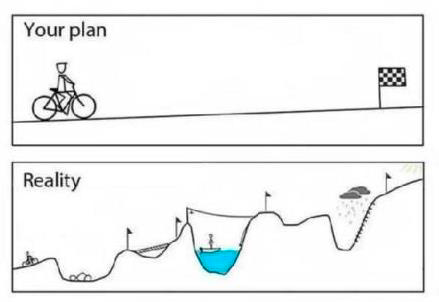

Many enter into collaboration thinking that the shared work is a linear and flat process from start to end. One of the favourite images describing collaboration that is often included in Tamarack power points is this image of plan versus reality. It captures the reality of collaboration including the twists and turns that collaborative efforts face as they move from start to completion. It can include obstructions like boulders and choppy waters and other challenges which are found obstructing the path along the way. This image always receives a small chuckle because individuals in the room have experienced these challenges.

However, the reality image still conveys a relatively linear, if upward, and challenging experience. This image is relevant for collaborative efforts seeking to achieve a result that is more defined such as the exchange of ideas, or development of a new program or service.

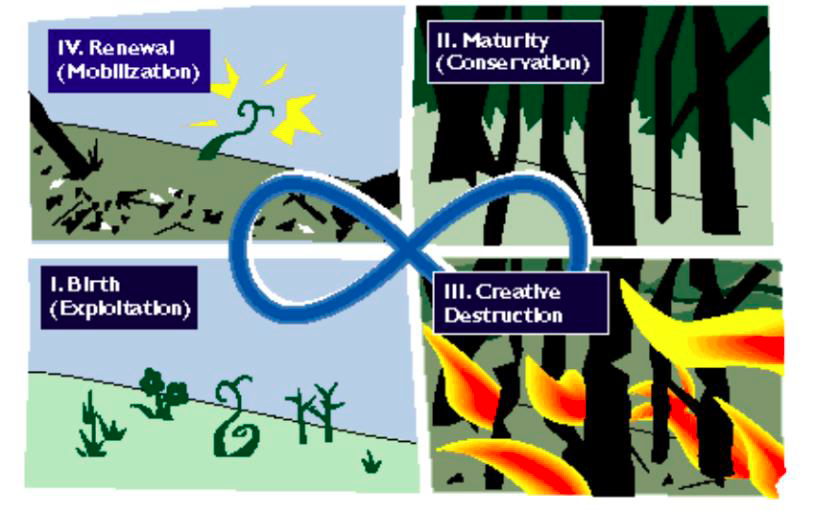

For more significant community change efforts, a different approach was introduced to Tamarack by Brenda Zimmerman of The Plexus Institute. Zimmerman described community change as a more cyclical process mirroring phases of development found in ecology.

The ecocycle concept is used in biology and depicted as an infinity loop. In this case, the S curve of the business school life cycle model is complemented by a reverse S curve. It is the reverse S curve, shown below with the dotted line, that represents the death and conception of living systems. In our depiction of the model, we call these stages creative destruction and renewal. The importance of the infinity loop is that it shows there is no beginning or end. The stages are all connected to each other. Hence renewal and destruction are part of an ongoing process.

Being an infinity cycle, there is no obvious start or end to the cycle. Let us begin our examination of the stages at the beginning of the traditional S curve. We will begin each phase by using the biological example of a forest and then look at the analogous phase in human organizations.(i)

The four phases of the ecocycle, as described by Zimmerman and the Plexus Institute follow the traditional (and linear) growth curve from birth to maturity. However, it also considers a renewal loop. The renewal loop includes a creative destruction phase and a renewal phase.

The image from the Plexus Institute website displays and describes the ecological cycle of a forest which starts with a variety of different plant growth (birth) which leads to increasing density as the forest grows to maturity. At maturity, the forest becomes increasingly vulnerable because of the density of growth. It can experience rot through invasive moths or pests or be ruined because of a forest fire. The creative destruction phase creates the space for renewal and regrowth. It is often the results of decay that enable the regrowth or renewal to seed.

Using the Ecocycle to Inform Our Practice

The ecocycle has been adapted by many organizations over the last several years to describe a better way of understanding community change and collaboration cycles. Tamarack has used the ecocycle to inform our practice of supporting communities tackling complex issues like ending poverty, building youth futures, deepening community, and navigating climate transitions. Tamarack, influenced in our early years by Brenda Zimmerman, recognizes that communities are dynamic and responsive. Even as collaborative tables begin to intervene in community change efforts, the community begins to respond, grow, and change. The ecocycle approach can be useful to collaborative tables to help understand and navigate dynamic change recognizing that change is not linear but rather exists in phases and cycles.

From Ecocycle to Collaboration Cycle

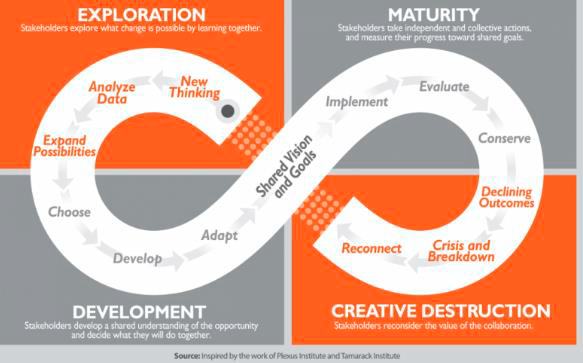

There have been many articles written about the Ecocycle and adaptations to this approach. One useful adaptation of the ecocycle was developed by Chris Thompson, Collaboration – A Handbook from the Fund for our Economic Future. (ii) In this handbook, Thompson adapts the ecocycle to a collaboration cycle approach. Thompson builds of the Plexus Institute ecocycle framework and Tamarack’s approach to adapting the ecocycle to community change efforts. Thompson uses the phases language of development, maturity, creative destruction, and exploration.

Thompson describes three elements which are vital to impactful collaboration: capacity, process, and leadership. The collaboration cycle is useful to focus on the process of collaboration.

This cycle serves as a roadmap for the diverse players who are along for the collaboration journey. It is invaluable to new participants joining an existing collaboration, as it can be used to help them understand where the partners are on the journey. Advocates of collaborations, particularly those performing the key collaboration functions, also should take the time to help each partner assess where they are on the cycle. Not every partner travels through the cycle at the same pace. (Thompson. Page 29) Thompson provides useful steps in each of the phases such as developing new thinking, analyzing data, and expanding possibilities in the exploration phase

In the development phase, the steps include choosing strategies, developing approaches, and adapting as the collaboration moves forward. The maturity phase includes implementation, evaluation and in some cases conserving to build on successful results. The creative destruction phase is initiated by declining outcomes, crisis, or breakdown and reconnecting.

Access the full article HERE

Liz Weaver is the Co-CEO of Tamarack Institute and leading the Tamarack Learning Centre. The Tamarack Learning Centre advances community change efforts by focusing on five strategic areas including collective impact, collaborative leadership, community engagement, community innovation and evaluating community impact. Liz is well-known for her thought leadership on collective impact and is the author of several popular and academic papers on the topic. She is a co-catalyst partner with the Collective Impact Forum.

Liz is passionate about the power and potential of communities getting to impact on complex issues. Prior to her current role at Tamarack, Liz led the Vibrant Communities Canada team assisting place-based collaborative tables to move their work from idea to impact.

featured image found here

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

3 COLLABORATIVE PRACTICES FOR ADVANCING SOCIAL IMPACT

Learning, for me, is more than acquiring knowledge; it’s also about putting it into practice and sharing my experiences so that others can benefit from them. Below are some good practices I’ve been using for bringing people across organizations together to collectively address complex challenges, like inequality and climate change.

1) Know what you’re good at and what your partners can do better. A gathering for members of a network I was involved in sparked an idea for a ground-breaking initiative. Shortly afterwards a couple of members volunteered to take this idea forward. In addition to hosting meetings for this new initiative, network staff contributed their technical expertise. This resulted in the development of a tool institutions can use to assess their impact and prompted industry influencers to comment on its potential to be taken to scale. At the same time, participation of network staff in developing this tool diverted resources from other collaborative efforts. While ‘the juice may have been worth the squeeze’ in terms of impact, my colleagues and I learned a valuable lesson in sticking to what the network does best—catalyzing innovative ideas that members can take forward together – instead of being an implementation partner.

Jane Wei-Skillern, who has spent more than a decade researching successful networks, defines network leadership as “mobiliz[ing] various organizations and resources that together can deliver more impact rather than to become a leading organization first and then engaging in collaboration at the margins.” Communicating the network’s role in supporting collaborative efforts to members has helped maintain positive relationships.

2) Add more value to gatherings by focusing on the most powerful leverage point in the system you’re working to change. My colleagues and I once organized a gathering for industry leaders to discuss addressing a gap in progress by political leaders. Instead of a series of panel discussions about who’s doing what and debating what needs to happen next, we took an unconventional approach. This involved turning the tables on what it means to act with urgency; we invited participants to pause and reflect on their actions and to assess whether the cumulative impact of these actions were collectively adding up to the impact they wanted to make. In this highly participatory meeting, we provided the space for participants learn from their peers and to decide what changes they wanted to make in their day-to-day work as well as in how they wanted to work together.

What made this an especially powerful gathering is that it centered on practical actions that can be taken at the individual level. We challenged everyone to consider: How do I relate to my work and the people I’m working with? According to Donella Meadows, in her influential work, “Dancing with Systems,” the most powerful place to intervene in any system is our mindsets. This is because institutions, societies, and cultures are all based on ideas, and ideas originate from how we perceive the world around us and interact with it. Changing our mindset begins with self-awareness. When we’re aware of our intentions and the impact we want to make, we can consciously choose to act in ways that increase the likelihood of getting desired results.

There was also enjoyment in exploring the irony that sometimes moving faster means taking time out to pause, reflect, and take care of ourselves. If we choose to keep running ahead on the path we’re already on, without pausing now and then to check we’re going in the right direction, we run the risk of losing our way and burning ourselves out in the process. This has been an important lesson for me personally as a leader of a small team that is under continuous pressure to deliver out-sized results. I’m getting more practice in simultaneously navigating the demands of systems change and self-care; I plan to share more on this subject in a future article.

3) Provide the space for failing and learning from it. I co-facilitated a series of dialogues for organizational leaders we convened to discuss opportunities to achieve a common goal they had been working on separately. When groups come together for the first time it’s important to provide the space to get to know each other, provide information about each other’s organizations, develop a shared understanding of the problem to be addressed, decide what to do together, and to build relationships that facilitate moving ideas into action. Accomplishing all of this in a way that leaves people feeling like their time is well-spent on both personal connection and making collective progress is a tall order, and even more so when busy schedules make it hard to meet.

In this situation, I erred on trying to accomplish too much in a short period of time instead of building in more spaciousness for connection and working together over the span of longer meetings or hosting meetings more frequently. As a result, these meetings felt rushed and, unfortunately, didn’t accomplish as much as had been planned. In hindsight, I could have done a better job of communicating expectations up front and also learning more about individuals’ motivations for participating early on.

This experience brings to mind FAIL as an acronym that Abdul Kalam refers to as “first attempt in learning.” This is a helpful reminder that when we’re working on complex challenges, like inequality and climate change, it’s unlikely that we’re going to come up with the perfect solution straight away; and even when there is a good solution, it takes time to experiment with how best to put it into practice and can be taken to scale. Co-creative, a consulting firm that specializes in collaborative innovation, calls for normalizing failure as a natural part of systems change. For more information on mindsets and practices for embracing failure in systems change, check out Co-Creative’s resource.

Redefining fail as first attempt in learning is also a reminder for me to be kinder to myself when things don’t work out the way I planned. I’m also learning to extend graciousness to myself as I do for my colleagues. One of my intentions for 2023 is to be intentional in providing the space for failure within my team and the networks I work with.

Kimberley Jutze is the founder of Shifting Patterns Consulting, a Certified B Corporation that helps changemaker leaders get their colleagues on the same page and put collaborative processes in place to achieve greater impact. Her company applies organizational and human systems processes that enable organizations collaborating at the intersection of social, economic, and environmental justice solve problems that prevent people from working well together in ways that stay solved.

Originally published by SEE Change Magazine

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

6 Reasons Why Liberatory Leaders Need to Take Play Seriously

When was the last time you played, did something just because it was fun and felt good? Did you finish feeling enlivened, relaxed, energized, or something similar? Leadership Learning Community has been exploring the roles of fun and play in our activities. This exploration didn’t start out super intentional, but rather as a reaction to the pandopalypse we’ve all been living in. Over time LLC began discussing play in relation to our work, referring to aspects of our work as “playful” or describing meetings and convenings as “play spaces.” For us, this isn’t a cutesy communications strategy. As LLC began to turn our attention to play, we realized that play, when grounded in collective purpose and steeped in values, can be a liberatory act.

Here are six reasons why we believe play can help leaders embrace liberatory practice.

Fuel Ideation

- Play can be described as “something that’s imaginative, self-directed, intrinsically motivated and guided by rules that leave room for creativity.” By creating space for creativity and imagination, play helps to quiet the self-conscious, judgemental inner critic. This voice discourages deviations from the known norm and makes trying on new things feel too risky. Without that voice, perhaps there is room for a little bit of magic to invite in new possibilities. Taking a playful stance allows us to adopt a child-like or beginner's mind, and helps us to develop mental plasticity and adaptability while simultaneously reminding us that our options aren’t all pre-determined and that there is space for the not yet known. This opening of possibility is critical as liberatory transformative efforts are dreaming and imagining into being something that does not currently exist. To do that, we have to stretch our imagination muscles.

- Practice: Start the meeting with a playful check-in question like, “If you could go back in time (or to the future), who would you want to meet?” or pick a favorite zoom filter to start the meeting with. Check out more of our check-in questions here.

Nurture, Healing & Wellness

- Play is an effective way to manage stress and can be a tool of both self and collective care. Play helps us to be in the moment, similar to meditation. In contrast to oppressive practices, which are confining and restrictive, sapping our spiritual and figurative energy; the enlivening nature of playful activities may help to heal these wounds.

- Practice: Host meetings near a park, the ocean, or in nature. Take a walk. Find new analogies for the work we do.

Create New Models of Strategic Thinking

- Playing makes things real, during play we don’t just imitate we also imagine and embody (something). Trying on liberation in play spaces/playful ways allows us to feel the benefit of liberation in the moment while we are learning more than we currently know. This focus on liberation now means that during play liberation doesn’t just have to be a future goal. In addition, some studies suggest that play supports memory and thinking skills, so play may literally help us think our way to freedom.

- Practice: Do some creative writing. Some of us have and are taking a writing course with Dara Joyce Lurie. She shares a quote from Edward de Bono, “Rightness is what matters in vertical thinking. Richness is what matters in lateral thinking. Vertical thinking selects a pathway by excluding other pathways. Lateral thinking does not select but seeks to open up other pathways. With lateral thinking one generates as many alternative approaches as one can. With vertical thinking one is trying to select the best approach, but with lateral thinking one is generating different approaches for the sake of generating them.”

Expand Leadership Opportunities

- Because play utilizes “creative rules” that are distinct from the rules and restrictions of regular life, in play, there exists the opportunity, though not the requirement, to separate capacity from expertise. All of a sudden, players “can” do things even if they aren’t experts at said activity. So you can play at being a pilot without actually knowing how to fly a plane. In playful spaces more people can function as leaders, meaning more people can be actively involved in imagining liberatory practice into being.

- Practice: Acting and improvisation exercises like “Questions Only” where you act out a scene given to you with only questions.

Build Community:

- Play offers us the opportunity to connect. When we create safe play spaces there is little risk to engaging. People can show up with a less performative stance. BIPOC leaders frequently find themselves under a spotlight or a microscope. The labor of being forced to code-switch or deal with being othered is exhausting so I imagine that BIPOC leaders especially are eager for safe spaces to be themselves. Where showing up as one’s whole self is an invitation and a demand, and for the purpose of supporting the BIPOC leader not to be of utility to others. Often BIPOC leaders are told to show up as their full self because observing BIPOC leaders is good for an observer, not for the benefit of the BIPOC leader.

- Practice: Shorten the strategic side of the meeting, and incorporate the karaoke, fun, and games as part of the meeting, not just extra at the end.

An Invitation to Wholeness:

- By allowing us to focus on pleasure and fun rather than objectives and outputs, play encourages us to be more than what we can produce. Perhaps play is akin to rest in that way, and maybe we can view embracing the revolutionary possibility of play in the same way that we have begun to respect how rest can be resistance. This need for play spaces may prove to be especially important for BIPOC leaders given that kids of color are often adultified early, and deprived of the space to play freely. By recapturing play, as we have attempted to reclaim rest, we may enliven our work and find new paths toward liberation.

- Practice: Make space for play at every meeting whether it’s a check-in, the location, the activities, or the bonding event. Make play and joy part of your community agreements so they show up intentionally during your work.

Ericka Stallings is the Co-Executive Director of the Leadership Learning Community (LLC) a learning network of people who run, fund and study leadership development. LLC challenges traditional thinking about leadership and supports the development of models that are more inclusive, networked and collective. Prior to LLC, Ericka was the Deputy Director for Capacity Building and Strategic Initiatives at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD), supporting organizing and advocacy and leading ANHD’s community organizing capacity building work.

Nikki Dinh is the daughter of boat people refugees who instilled in her the importance of being in community. Though she grew up in a California county that was founded by the KKK, her family’s home was in an immigrant enclave. Her neighborhood taught her about resistance, resilience, joy and love.

originally published at Leadership Learning Community

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

by Ericka Stallings and Nikki Dinh, co-executive directors of Leadership Learning Community

Strengthening Social Connection and Opportunities in Rural Communities

This brief describes an unfolding learning journey intended to strengthen social connection, resident voice, and agency to address inequities in rural health and well-being. Along the way, we have come to realize the important lessons for each of our institutions and ways in which we are better off for having taken this approach to our work.

At St. David’s Foundation, we believe that realizing health equity to minimize the consequences of poverty and racism reflected in the social determinants of health is foundational in our work in Central Texas. Rural communities are dramatically under-represented in philanthropic investments nationwide and in Texas, and the Foundation’s own balance of investments skews toward initiatives that serve urban populations. When philanthropic dollars are invested in rural communities, they are typically directed to the few established nonprofits and local government entities that implement programs or provide services to residents. Community members, especially people experiencing vulnerability and isolation, are rarely asked what they need to improve their health and quality of life and how they may utilize the power inherent in their communities to contribute to those improvements. The most common observation from the philanthropic sector is that “these residents” are rarely poised to receive and control funds to work on the issues they believe are most important for the health and well-being of their own community. Listening and enabling capacity can change that.

Listening to our Rural Neighbors

After a sustained period of building deeper ties and stronger relationships in our rural communities surrounding Austin and Travis County, the Foundation learned that many of our rural neighbors felt disconnected from and ignored by the Foundation and local decisionmakers in their communities who decide how resources are prioritized and distributed to address community needs. Residents from the surrounding rural counties of Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays, and eastern Williamson County expressed an interest in working with the Foundation and their peers on priority concerns including youth, mental health and substance use and misuse, food insecurity, and affordable housing.

Community Capacity Building and Enabling as Rural Strategy

In partnership with The Strategy Group (TSG), a national consulting firm with expertise in catalyzing resident-led community networks focused on health and well-being, the Foundation invested in community capacity building (CCB) strategies to engage interested residents in working collaboratively on issues of importance to community members and enable their inherent power to participate in problem solving.

Informed by residents, the Foundation and TSG co-designed an approach that incorporated key community capacity building outcomes so that residents could develop their own solutions to pressing self-identified community health concerns. TSG also offered a process for the Foundation to build its own capacity to invest differently in rural communities— an approach that invested in network infrastructure, resident leadership development, nonprofit leadership to partner with and support community networks, and connected people experiencing vulnerability and lack of connection to opportunities for community development.

The Foundation’s rural strategy centered social impact networks (Plastrik et al 2014), network weaving (Holley 2012), and sustained community engagement to create an expanding, diverse, inclusive resident-led network focused on health and wellbeing -inequities often reinforced by historical and structural legacies of exclusion and privilege. Stuart (2014) notes, “this is one of those cases where a commitment to social justice is crucial. It is important to consider who is included in the “community” that is leading the process. Who is excluded from community leadership? Whose voices are missing from community debate? Whose interests are being served?”

And if the community is driving decisions about their own development, what does that mean for how the Foundation should be investing in community?

Centering Equity and Equitable Opportunity

As St. David’s Foundation has embraced and prioritized health equity, rural investments evolved to become more place-based and community-focused. How the Foundation showed up in the community (and how frequently), how grant opportunities were presented, and how funds were distributed when CCB was the overarching purpose changed the nature of the relationship between funder and community. In our rural work, the Foundation recognized that a portion of our rural investment needed to give the community control over decisions and resources to determine what resources were needed to spur or make lasting change.

Bringing it all Together in Central Texas

The community network approach in Central Texas prioritizes:

- Centering the voices and lived experiences of rural BIPOC residents (equitable opportunity);

- Seeding a network of interested resident leaders who have a deep understanding of their and their neighbors’ needs to direct their own community development work; creating new relationships; and offering new ways of working, thinking and leading in community; (i.e., social impact networks);

- Engaging and supporting local residents to organize themselves to work on projects that move the community from talking about problems to taking action on problems (i.e., self-organizing);

- Supporting residents who want to develop the leadership skills to engage other residents to work together in a resident-led network focused on health and wellbeing (i.e., network weavers); and

- Putting a pool of resources into the hands of those who have the lived experiences of health inequity, poverty, social isolation; are closest to community problems; and who want to work with their peers to improve community health and wellbeing from a solidarity stance.

What are Networks and Network Weavers?

Social impact networks (like the ones emerging in Central Texas) are constellations of people, organizations, and communities connected by a shared purpose to make change. In the Central Texas network, there is a high-level purpose to improve the health and wellbeing of residents in the region.

Network weavers are residents in the Foundation’s rural service area who have chosen to be a leader in the network; they are the “engines” of our regional network. Weavers strategically connect other residents, convene groups of interested residents, coordinate small projects aligned with resident interests and needs, and work to grow the network and the projects the network is interested in pursuing. Holley (2012) describes a network weaver as “someone who is aware of the networks around them and explicitly works to make them healthier. Network weavers do this by helping people identify their interests and challenges, connecting people strategically where there’s potential for mutual benefit, and serving as a catalyst for self-organizing groups.”

The Foundation provides operating support for TSG as well as funds to support network infrastructure (e.g., communications, evaluation, training, storytelling), stipends for weaver leaders, and shared gifting circles. To date, over 100 residents have been trained to be network weavers in Central Texas.

Building Community Leadership

The Foundation’s investment in community capacity building by catalyzing resident-led networks and training residents to become network weavers is designed to engage and support residents to contribute their time and talents (i.e., community leadership) to solve pressing self-determined health and wellbeing challenges in their own communities. Residents also participate in monthly peer assist sessions which enable real-time feedback and advice from peers as they practice their leadership skills.

Participatory Grantmaking

Using participatory grantmaking processes and resources, network weavers are supported to identify local problems and then work collaboratively with other residents to co-design and test solutions. Shared gifting emerged as an important participatory grantmaking tool to support weavers during the second year of project implementation. We asked ourselves: “how can a small pool of grant funds be used to foster connection across different communities and authentic collaboration, rather than competition?” Shared gifting allows residents to decide what the most urgent community needs are, rather than the Foundation, and then to grant dollars to community projects they wish to support. There are no required outcomes of the process other than what is determined by the participants during the shared gifting process.

From participant reports of the shared gifting process, we were excited to learn that a shift in control of grant funds from the Foundation to the group of network weavers (residents) created an environment of social connection, equity, encouragement and support, feelings of abundance, and community. The typical grantmaking experience of competition and scarcity often experienced by potential grantees when responding to competitive grant opportunities was not reported by participants. Instead, weavers were excited to make new connections with other weavers, hear about new projects happening in their community, extend offers of time, talent, and treasure to other weavers, and expressed pride to be able to support those projects with the resources they controlled.

Conclusion

Residents who have participated in network weaving and participatory grantmaking have shared a common experience of personal and professional transformation, social connection, empowerment, and awareness of new possibilities and promise for their communities. The Foundation’s experience of investing in rural communities and its people by creating opportunities for resident decision making about how resources should be directed to pressing issues in their communities has revealed new possibilities for grantmaking and use of our social capital to advance the health and wellbeing of rural residents in Central Texas. Further, the experience with weavers as grantmakers underscores the importance and urgency of integrating community voice consistently in the Foundation’s equity-driven journey.

Voices and Learnings

Network weavers were invited to share their thoughts on how weaving has influenced their personal and professional lives. The themes found in their comments were that network weaving:

- Offers both professional and personal value to persons.

- Provides a framework that is valuable to tackle complex community issues.

- Facilitates making connections that create change in the community.

- Allows the use of shared gifting as a unique learning, connecting, and growing experience.

- Fosters among network weavers a desire to build new skills and capacities to continue to strengthen their work within their own communities.

- Encourages persons who had existing networks to make those networks more effective, efficient, and stronger by implementing what they learned in the Network Weaving learning opportunity.

“Weaving has tremendous value as it has empowered me to create with others outside of my usual network, helping to expand my reach and capacity to support others.“

“Throughout the past few years, in a mid-COVID society, Network Weaving has proven to be a skill set and collective necessity to maintain community collaboration. As work-life has evolved and more individuals experience isolation, Network Weaving has made the ability to connect (in-person or virtual) a go-to process for me in my personal and work life.“

Krystal Grimes, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Ultimately, all of us have the same end goal of building a better community. We all are here for the same reason; we’re all doing this work because we have a passion for community building. And network weaving has really given us that opportunity.”

“It has given me a really clear framework for what I’m doing. It’s not something that lives in my brain. Now. it’s an actual process and an actual framework that I can utilize to share information.”

Elizabeth Marzec, 2021, Organizational Leader, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Helping the community that you live in, helps you, it helps your children and helps your grandchildren. So, I think that is the point in the future that weaving really impacts.”

Linda Quiroz, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Bringing leaders together, making community change, and having people who never thought of themselves as a leader know that they can all make a difference. I love that.”

Kathleen Moore, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“Prior to network weaving, I had no idea how to get this passion, this idea realized . . . I’m trying to be involved in the community. But I needed direction. I needed ideas, I needed strategies. And so, when I was invited [to learn about network weaving], it gave me what really felt like a breath of fresh air, because I’m going to be around peers that can help me along the way. And then also for me to help others.”

Sonya Hosey, 2021, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

“I think about the word power. And that power is shared. It doesn’t belong to one person or group . . . and I love that about network weaving,”

“I have watched the whole design of network weaving just open this road for people to speak and share and dream, and nothing is impossible”

Maureen Stanek, 2019, Shared Gifting Grantee/Grantmaker

References

Holley, J. (2012). Network weaver handbook: A guide to transformational networks. Athens, OH: Network Weaving Publishing.

Moore, W. P., Klem, A.M., Holmes, C.L., Holley, J. and Houchen, C. (2016). Community innovation network framework: A model for reshaping community identity, The Foundation Review, 8(3). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1311.

Plastrik, P., Taylor, M., and Cleveland, J. (2014). Connecting to change the world: Harnessing the power of networks for social impact. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Stuart, G. (Apr 10, 2014). What is Community Capacity Building? Impact Initiative.

Abena Asante has over twenty years’ experience in philanthropy, public health, and the nonprofit sector. A senior program officer at St David’s Foundation, she leads efforts that catalyze community action around issues and opportunities that align with the Foundation’s firm commitment to achieve health equity.

Dr. William Moore is Principal at The Strategy Group, a Kansas City-based international consulting firm supporting nonprofits, foundations, and communities. Bill is a Senior Fellow at the Midwest Center for Nonprofit Leadership at the University of Missouri – Kansas City, Senior Associate for Rural Health at the Texas Health Institute, and is the rural health advisor to the St. David’s Foundation.

originally published at gih.org

A in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and studied at Sciences Po, Paris as an Erasmus scholar.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Community engagement: How to create meaningful connections in an age of distrust

Community engagement is a term applied in various contexts, often meaning different things to different audiences. It is sometimes used interchangeably with other concepts such as community outreach or community consultation. For the purpose of this article, we utilise the term community engagement to describe a process where local government, charities, and funders collaborate meaningfully with the communities that they serve.

The insights presented in the following text are informed by our experiences working with the above groups. We hope this article is particularly useful to those who are hoping to build stronger and better-informed relationships with their communities.

Community engagement

Community engagement is a key part of any project or programme that seeks to directly enhance the lives of the public. When providing services that affect people belonging to a defined area or group, building relationships within that community is a non-negotiable. Whether you’re a charity, funder or government authority, understanding what communities are thinking and feeling, and taking those thoughts and feelings seriously, is the only road to a legitimate and meaningful partnership.

What is community engagement?

Why is community engagement important?

How should I approach community engagement?

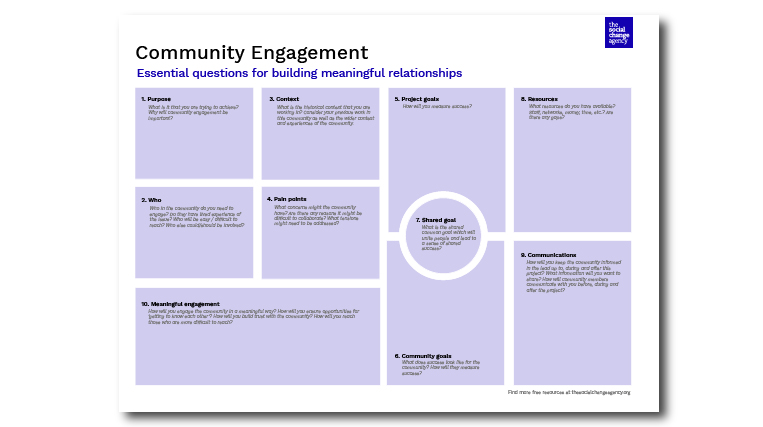

Download The Community Engagement Canvas [Free Resource]

What is community engagement?

Community engagement is all about supporting communities to take ownership of the resources that are available to them. This means taking an active role in creating partnerships between the institution that is providing those resources, such as a local council or charity, and the communities that will be receiving them. Grassroots, voluntary and faith organisations as well as mutual aid groups are deeply embedded in their communities and have a great understanding of local dynamics. This is what makes them such important partners for service providers.

In the simplest sense, community engagement is likely to involve connecting with community leaders and facilitating conversations about what they would like to see happen in their communities. This might look like restoring public spaces such as libraries or a community garden, engaging in discussions around improving housing standards or planning and programming a community event.

Why is community engagement important?

Over the last two decades, trust in ‘big’ institutions has been in a state of flux. Historical events such as Brexit and more recently COVID-19 have shifted our understanding of public life and how we relate to the institutions and organisations that shape it. The latest British Social Attitudes Survey reported that only 23% of people trust the government to put the needs of the nation before the interests of their party. So, how can those with institutional power begin to build back trust with the communities that they serve?

An approach gathering momentum in the US termed ‘earned legitimacy‘ puts forward the argument that it is the role of public institutions to build bridges with communities who have lost faith in their ability to serve. More specifically, it suggests that a public institutions’ legitimacy hangs directly on how much their community trusts them to act justly on their behalf.

Government might be a useful example to illustrate the meaning of earned legitimacy, but we believe that this approach is a solid one for any organisation that has the power, resource and will to engage communities in their activities. In short, it’s on you to put the work in.

How should I approach community engagement?

1. Get real about the role of history

When you work for a long-established organisation with substantial control over wealth and resource, people are likely to have pre-existing ideas about what you do and how you do it. Historically, many communities have been underserved and even harmed by powerful institutions. We see examples of this frequently in the news, whether it’s black individuals being more likely to be subject to stop and search or international charities such as Oxfam’s failure in preventing abuses of power. It makes sense that some communities are sceptical to work with those that have represented racism, mistreatment and harm to them in the past.

‘What are your concerns about this organisation and is there anything we can do to reassure you?’

The Centre for Public Impact recently released a report on how they went about restoring trust between Americans and local government by working with local communities in four different parts of the US. This involved “acknowledging past wrongs and showing a commitment to confront[ing] present-day […] issues.” The report highlights how important it is for historical tensions to be addressed with openness and honesty, especially in the early stages of relationship-building. This may involve asking community members questions such as ‘How do you feel about working with us?’ or ‘What are your concerns about this organisation and is there anything we can do to reassure you?’ before embarking on a shared venture.

2. Recognise that expertise exists within communities

The starting point for community engagement should almost always be that nobody understands what a community wants and needs better than the people belonging to the defined group. Big institutions often work with experts and consultants to problem solve and generate solutions. The Social Change Agency believe that the answers exist within communities and it’s really about creating safe spaces where those insights can be shared. If you are engaging communities in a consultation process, it’s worth considering that individuals should be paid for their time. They’re the real experts.

3. Getting to know each other is work too

With deadlines, budget restraints and the pressure to demonstrate outcomes, we often want to skip small talk and get right to the finished product. If you have the power to write ‘getting to know each other’ time into your project plan, this could really support relationship-building with your community and will almost definitely make things more efficient in the long run. Taking the time to visit the people you’re hoping to engage with and really understanding what motivates them can help to create the conditions for a durable partnership.

4. Communication, communication, communication

Whether it’s email, Slack, WhatsApp or Facebook, the way we interact often shifts depending on audience and urgency. This is no different when we are engaging with community networks. If barriers to communication emerge, it can drastically affect your relationship and slow down the pace of delivery. At the very beginning of your community engagement endeavour, ask community members how they would like to be contacted and what is most convenient for them. Make it as easy as possible to connect but create boundaries around how often and when is appropriate to communicate. This will give you a solid vehicle via which collaboration can flourish.

5. Defining success together

What success looks like to communities and what success looks like to funders, governments and charities are often two entirely things. Success to a local authority might be engaging 20 different community groups in a consultation process before opening a new digital community hub. Community members may visualise success as guaranteeing this space is free to use for certain age groups.

A way of define shared success might be creating an accessible and affordable digital hub designed by and for the community. It’s worth having a conversation about what both of your ambitions are for working together and creating a sense of shared purpose in your collaboration. Establishing a common goal is likely to keep you connected as you move through the logistics of delivery.

originally published at Social Change Agency

Maisie Palmer 's interests lie in social innovation, education, and supporting community-led movements. Prior to joining our consultancy team, she was National Programme Lead for Education at The Roots Programme where she designed and delivered an exchange programme tackling social division amongst British youth. Maisie founded Mxogyny an online and print publication for marginalised creatives. She has also worked for the Secretary of State for Scotland and the International Criminal Court. Maisie holds an MA in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and studied at Sciences Po, Paris as an Erasmus scholar.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Weaving at Work

Over the past few years, I have been increasingly influenced by the concept of “weaving” — what for me means connecting people, ideas, and projects to foster more collaborative social change.

Weaving is a skill, a mindset, and a way of being. More art than science, it requires deep listening, being responsive to interests and needs, and “sensing” opportunities to bring people or projects together.

In many ways, it’s synonymous with other terms we use like facilitation, collaboration, networking, community building, relational leadership, etc.

I find weaving to be an incredibly powerful tool for fostering collaboration, decentralizing ownership, and sparking wide-scale impact.

But weaving often clashes with our traditional workplace habits and structures

One of the things I’ve been struggling with lately is how to make weaving a regular and consistent part of our team.

In the network I run, despite multiple attempts weaving still doesn’t show up in our to-do’s or our impact tracking system. When our time is limited (which is almost always), it quickly becomes a “nice to have”.

Often, we work in systems that are linear, logical, and task-based—from project management, to communication and coordination, to data analysis. Weaving is by nature more intuitive, emergent, and relationship-focused, and sometimes just doesn’t seem to fit.

As a result, weaving can be hard to integrate into our task lists, to coordinate across our team members, and to openly report on. And because our managers and supporters usually don’t see or experience it themselves, it can go unnoticed and misunderstood.

So how can weaving become a core activity that we regularly practice and valorize in our workplaces?

Last week, June Holley and I hosted a brainstorming session with the Weaving Lab around this question. Here are some of the ideas that came up:

- Weave everywhere, all the time — and explicitly state that you’re doing it. For example, in interviews you can cluster small groups of people who don’t know each other and tell them relationship building is a core goal of the interview. In team meetings you can leave time for storytelling and explain why this is important for building trust. In large group events you can integrate simple getting-to-know-you activities, and explain how connections are the core of any collaborative work.

- Explicitly write weaving in our daily task lists. Be they digital or analogue, try to make sure weaving is written down as a regularly-occurring task (e.g. weekly) for each team member. So even when a direct opportunity for weaving doesn’t show up to you, your job is to “find” one.

- Enable weaving through a light-touch database system. Keep an updated list of your team and community members’ needs, interests, gifts, skills, fields of work, engagement level, etc. Make it simple, so it’s easy to skim. And use your weekly task to actively “identify” new opportunities for weaving (don’t expect community members to do this themselves!). For example: find 3 people who haven’t met but you think would get along and introduce them to each other. Or, share a funding opportunity with 4 people working in a similar field of interest. By the way, CRM systems aren’t set up for this, so consider using a flexible tool like Asana or AirTable, or a network mapping tool like Kumu.

- Don’t weave alone or in isolation — weave with others. Mark “weaving opportunities” as a fixed item in your team meeting agenda. This helps you better coordinate to avoid overlap, be creative in finding weaving opportunities, and be accountable to making it happen, while also building a culture of weaving. One note:make sure your team has diverse weaving capacities so you can complement each other.

- Document and share weaving through simple and regular processes. Integrating weaving updates into your team meetings—e.g. “what relationships have we build this week” — so you capture and share things you may not have recalled. Have a simple “checklist” for immediately logging when weaving occurs (make it super easy, 15–30 seconds to open, log, and close). And do annual surveys and check-ins with your community to see what impact weaving has had over time.

- Help people whose support you need (e.g. bosses, funders) to “get” it. Use common concepts and metaphors that can make weaving easier to understand. Collect stories of weaving and share those with them. Invite them to to engage directly in weaving practices (e.g. a peer-to-peer problem-solving session where they can get support on a challenge they face and experience weaving in practice). And hold multiple meetings with them where you let them can ask you questions and get to know the practice better.

What would you add?

Brendon Johnson is a seasoned changemaker with a passion for strategies and models around networks, communities, participatory organizing, and collaborative action

Originally published at Medium

Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Applying regenerative practice to systems beyond place — some thoughts

By way of introduction: spiky fruit

It’s the first of October, and I’ve been writing this piece for over half a year! Yesterday this cactus caught my eye. The spiky leaves and the ripe fruit spoke to me of the necessity to take these unpolished thoughts and offer them up. If handled carefully and peeled, the juicy prickly pear can make a great salad. It’s painstaking and potentially irritating work. The flesh is not as flavorsome as other fruit, but it’s what grows and abounds here and now. So perhaps you can enjoy the thoughts that follow in that spirit!

Rising to the challenge

Our societies and our living planet are struggling to survive with the threat of climate change, mass extinction of species, depletion of the living resources of soil on all our continents — the list goes on. In the face of this regenerative work offers the hope of enabling the extraordinary capacities of living systems to adapt and create the conditions conducive to life.

There is an active community of regenerative practitioners supporting change-makers the world over to work from the principles of living systems in order to revive and evolve the places and the systems they are working with. Living systems are grounded in places, adapting to local conditions and contexts, evolving strategies to thrive in the myriad diversity of environments, from hot deep sea vents, to estuaries where sea and land intermingle, to cloud forests of the tropics, to green ‘deserts’ of grassland. The source of regenerative practice is found in the dynamic relationship of life and place, and the inevitable relationship of people to and within other living entities. People, human societies, are living systems, and as such we are deeply connected to the places we live and depend upon.

However, as human societies have evolved over the last few hundred years into a global civilization, and many of the challenges we face are playing out on the scale of the whole planet, regenerative practitioners are called to find ways to apply our living systems approaches to activities that seem disconnected from “place”. When we look to change international business supply chains, when we design digital services, when we think about what sustainability means for huge global retail corporations, how can we bring regenerative practice to bear? In an age where the shift to online working has been accelerated through the Covid-19 pandemic, and I write this from a co-working space in the south of France as part of a team with people across four continents, how can the potential of life-regenerating work step into and beyond hyper-local “place” as a contribution to a societal shift so needed this decade?

What follows are a few thoughts, deeply influenced by my work and dialogues with Regenesis, Future Stewards and other regenerative practitioners. These thoughts have formed as I apply this practice to the School of System Change, an international endeavour to support change-makers navigate the field and practice of systems change, growing their capacity to work with complexity and uncertainty, and to contribute to great shifts in business, civil society, government, communities and philanthropy.

Disconnected from place?

I deliberately speak of activities that seem disconnected from place. Our human capacity to understand ourselves as disconnected from nature, from living systems, from place, has been honed over several hundred years of Western mechanistic thinking. Those of us who have learnt to understand our world in this way continually develop constructs — both physical and conceptual — that reinforce this premise of separation or non-dependence on life. We build global digital platforms with remote-working teams. We manage supply chains from warehouse to container to truck to logistic platform to supermarket in a complicated chain through multiple built environments made of concrete, metal, tarmac. We speak of dematerialised banking, and have decoupled finance from the “real” economy. We manage agricultural production through sterile seeds and petrochemical fertilisers.

I have learnt to see how all of these activities are nested within the living systems of our planet. The people working behind their screens or their steering wheels are alive, they need food to nourish them that is alive too (or at least was recently!). Our businesses, communities and cities are complex living systems with the same needs and metabolic functions as a forest ecosystem: nourishment for energy, clean water, purification of waste, temperature control… The people and places impacted by “dematerialised” activities may be widespread and seeminging disconnected, however they are indubitably alive, and in many contexts in need of activating their regenerative potential to tackle increasingly difficult issues of physical and mental health, pollution, soil degradation, and adversity.

Pretending that a human activity has no grounding in living systems and places — because of its digital or global nature, because it involves commodities sourced via intermediaries and their warehouses — carries a high risk of creating harmful externalities to the living systems that are inextricably linked to these activities but remain invisible in our designs. This decoupling of our activities from the living systems we operate within perpetuates the deep-seated pattern that has led to the crises we are living into today, from climate change to the global pandemic.

Putting living systems back in the equation isn’t easy work, but it is possible, and deeply rewarding. Where might we start?

I am offering three sets of practices that can support a regenerative outlook, even when working with systems that seem disconnected with place:

- Seeing life in everything

- Working with specificity not generic outcomes

- Starting with the care we hold for our fellow living beings

Seeing life in everything

The first set of three practices are helping me develop my ability to see living entities — people, organisations, places — as alive.

Working with qualities of aliveness

One of the ways I have learned to do this is through noticing three qualities of aliveness (from Regenesis):

- evolution — organic development and unfolding, where things aren’t going to plan, but are moving and adapting to uncertainty and complexity, and there is no going back!

- viability — relational dynamics that are necessary to survival over time, relationships to wider ecosystems, be they food webs or markets or fields of shared endeavour; and

- vitality — the spontaneous expression of life force, uniqueness, purpose and energy that can be felt when a person or an organisation is flourishing

These qualities are interrelated — the vitality of a living system needs nourishment to be viable over time, and continuously adapts and evolves as the world changes around us.

Noticing these qualities helps me engage with living systems — including human systems seemingly disconnected from the living world — as inherently alive. It is also a way into identifying which capacities might need enhancing to ensure ongoing life in these systems.

Changing metaphors

Our mechanistic ways of thinking are deeply anchored in metaphors we use all the time! So I practice changing the metaphors and looking for life-sourced images to describe what’s going on. How might we grow capacity rather than build it? How might we look for nodal interventions rather than leverage points (a node refers to a place in a living entity where many flows come together, whereas a lever is a component in a machine)? How might we seek evolution not scale?

Sometimes the more ecological or metabolic metaphors can seem a bit too hippie, and I don’t always adopt them, however the conscious practice of identifying which paradigm I’m thinking from through the language I employ is very insightful. I have noticed how comfortable it is to revert to terms that imply predictability and the ability to control outcomes! (building capacity, driving change, measuring impact — just some examples) Adopting life-sourced metaphors implies leaning into uncertainty, working with what is emerging, and thinking of what I do as a contribution to wider work.

Looking for connection to place

The third exercise is trying to ground the systems I’m working on in place — even if these places are multiple and seemingly disconnected, like across a supply chain. Reminding myself that life is rooted. That even hydroponic agriculture relies on nutrients that have come from the living earth — somewhere! Our office sites have footprints on the ground, and are situated in complex ecosystems.

Envisaging the ways in which our activities are connected to and dependent upon living places, and then questioning the impacts on the vitality, viability and evolution of these places — at multiple scales — can yield insights both devastating and full of opportunity for change. Devastating because we might notice how much life has been destroyed as we create an inert built environment for ourselves, for example pouring concrete over the earth so that the microorganisms beneath will be disconnected from the flows of water from rain and nutrients and energy released into the soil through plant roots. Full of opportunity because we can amplify the extraordinary qualities of life which will continue to evolve and regenerate, through multitudes of human innovations that work in symbiosis with the living world.

Looking for this connection to place in the history of the organisation is often a good place to start, as the identity and culture — however international in its operations — may well be imbued with the unique characteristics of the ground it sprang up from in the beginning.

Working with specificity not generic outcomes

This set of practices is helping me work with the unique characteristics of the systems I’m involved with to identify differentiated and coherent strategies for action, producing unique and positive outcomes.

I often hear the ask for a definition or catalogue of what might be “regenerative outcomes”. In the face of the crises we’re experiencing, and with the best will in the world to effect positive change, people and organisations want answers, and clear how-tos. I hear the urgency, and the need for simple, actionable responses. However, I am learning to first respond with a set of questions to reach differentiated answers — as living systems are differentiated and there is no one-size-fits-all. The set of questions below can quite quickly lead to answers that in turn will be much more powerful in unlocking life-regenerating processes.

The overarching starting question here is What is the essential characteristic or nature of what we’re working with?

Some of the ways into this question are

- What is the unique purpose of this business or endeavour (which may be deceptively different from the mission statement, being more what is alive in the business as a whole, it’s core pattern that repeats across scales from teams to international operations, and configures this organisation’s contribution to a wider sphere)

- What is the core property of the material / commodity / species we’re working with? How might we work with the inherent properties of aluminum, or cotton, or soap — for example — to work out how these can be expressed in service of life?

- What are living systems like round here? How have they — people, plants, animals, micro-organisms — adapted to the specific living conditions of this place? What might we learn from these strategies?

Starting with the essential characteristics of what we’re working with is a route to seeing the potential that could be expressed if we lifted these up to serve a living world. It can help us be open and curious. We can move beyond the generic plan to “plant trees”, to question which essences, which combination of context-appropriate species, we might encourage in this particular place.

We can go further to understand that if we’re a clothing company, for example, planting trees is all very well but it doesn’t harness the potential of the core of what we do — the living materials, people and identity that are at the centre of our activity. The regenerative contribution of a luxury brand will be distinctly different from that of a high-street clothing brand. Recognising our unique approach, and going beyond market differentiation to putting this in service of the living systems we’re involved with, will highlight practical actions we can take leading to powerful regenerative outcomes.

Starting with the care we hold for our fellow living beings

One of my recent insights about regenerative work is that it stems from a deep care about the world, which taps into vulnerability, and therefore requires a certain kind of intimacy and attention. When we care, we are in relationship being to living being. We can be curious about what is specific about what is happening here and now, we can be empathetic — feeling from the place of the other, we can work with emotional and intellectual intelligence together, bringing our whole selves to the situation at hand.

It’s difficult to talk about how much we care for the living world in situations where everything around us (our office space, the board room, our managerial practices, our scheduling habits) are designed from mechanistic assumptions and “man-made” materials. Paying attention to what is alive, even in these contexts, can require a shift in how we show up and what we are giving our attention to. Put another way, it’s about being as much as doing.

This leads to a new set of questions around the enabling conditions for some of this work:

- How might we let ourselves see our fellow workers, customers, citizens as whole people striving to live nourishing lives?

- How do we move from concern for a statistic (e.g. numbers of mental health-related emergency calls) or worry about a trend (e.g. decreasing yields from ever poorer soils) to care about the living beings — the people, the ecosystems of microorganisms in the soil — we’re so interconnected to?

- What are the qualities of space we might need to tap into this other way of knowing and deciding what to do in the face of the overwhelming challenges we’re facing?

Bringing regenerative practice home

I know I’m a conversational learner, and I thrive in deep conversations and spaces of inquiry around these sorts of questions. I can see how through these collective moments my thinking about the world is evolving, and informing my work in the long term. I also practice micro-experiments to take my thinking into my daily life in a shorter timescale — these range from spending a whole summer without killing a single mosquito as an experiment in respecting the equivalence of life-forms, to fermenting kimchi in my kitchen, to applying the vitality-viability-evolution framework to all sorts of projects, situations and relationships at work and at home through five-minute sketches.

This may not be your way of connecting with aliveness. At an online team meeting a few months back I was struck by the beautiful diversity of situations when people feel most alive — from on a sea shore, to being in crowded public transport. If you invite yourself into a space of caring for the living world for a moment, what is it you notice? And how might you carry that with you into the big, wide world, as a root to help you with your very unique contribution to systems change?

originally published at School of Systems Change

Laura Winn is head of the School of System Change at Forum for the Future. She works to develop the School as a networked organisation that supports change-makers from diverse backgrounds and contexts, providing them with new capabilities to tackle an increasingly complex set of sustainability challenges. Laura's own practice stems from living systems and regenerative approaches, learnt and applied across multiple small-scale and large-scale projects.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

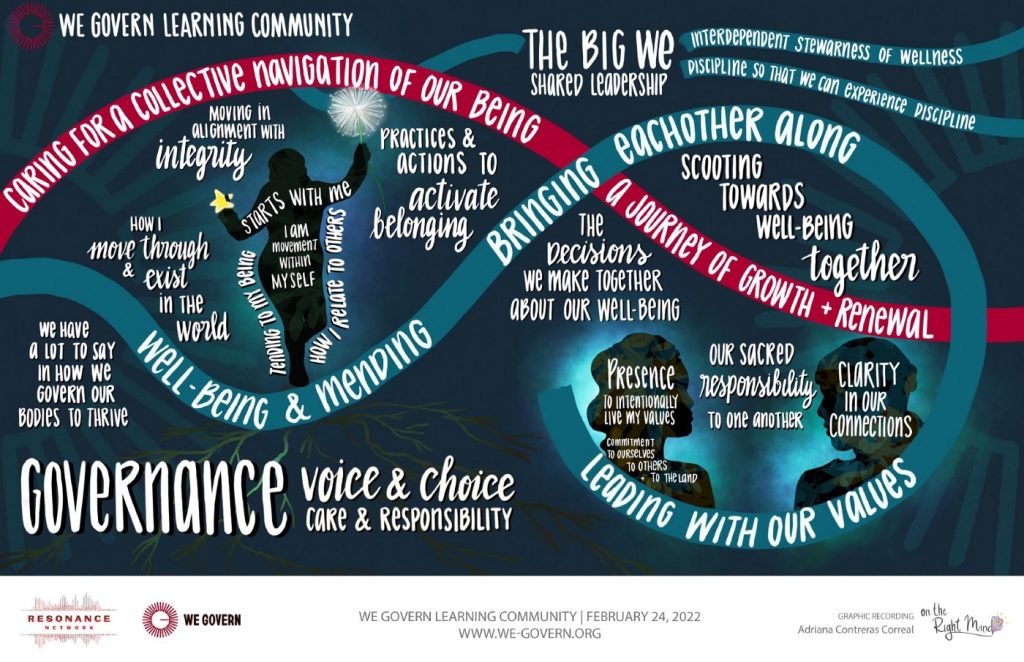

Being in the humanity of governance, with all its messiness and joy

Reflections from the WeGovern Learning Community

How do we build ways of being that uplift the collective dignity, wholeness, and thriving of one another and the lands we inhabit?

How do we build ways of being where our collective wellbeing is carried by community?

How do we create opportunities to live a happy life? To find joy?

WeGovern Learning Community participants are exploring these questions together–discovering what it takes to live into the WeGovern principles today, in our current realities and communities.

This is collective governance, and it takes practice.

* * *

In phase two of the WeGovern Learning Community, a cohort of new and returning participants came together with a shared commitment to collective governance–in practice, embodiment, and reflection. In their first gathering, cohort members delved into what governance means to them, and how it shows up in their lives. Here are some highlights from that conversation:

“I am a movement within myself.” ~ Monique Tú Nguyen

- I used to think there wasn’t a clear rhythm to the way I make choices–that it just sort of happened as things came up. But when I reflected on it, I realized I have a methodical way of making decisions–with myself, choosing who I spend time with and what I spend time doing, and how I care for myself and use my resources emotionally, physically, spiritually, and financially. That’s governance, and there is power in that clarity.

- At work, we have to be clear about documentation; there are clear pathways and decision making protocols–but how are we clarifying, for ourselves, the pathways toward decision making in our own lives, and in our interpersonal relationships?

We are stepping into the sacred responsibility of tending to our own being-ness

- If we are going to be in relationship and connection with others, we have a responsibility to tend to our own being–our own healing, our own growth. Everything else comes from that place–our practices, our placemaking, how we cultivate belonging, and how we become aware of our needs–and make choices to make sure those needs are met.

- It is the values and choices that I practice every day, in all the unfolding moments. I am choosing wholeness and listening and vulnerability

“When I think about the ways I engage with governance the most, it’s in the relationships I touch every day–my relationship with myself, my relationship with my dog, my relationship with my partner, and in my caregiving relationship with my mom, who has dementia.”

-Alexis Flanagan

There is power in visibilizing our governance practice(s)

- And it’s important to name governance as governance — to visibilize our practice, so we can bring people along

- We are cultivating a sense of responsibility for the way we move through the world. From the moment we get out of bed in the morning, how are we living our values? It’s so easy to let that process be invisible, but so important to bring it to light.

Governance is the gas pedal on the tractor

- If I imagine my life as driving a tractor, what’s accelerating me forward is my own choices. I want to move forward in alignment and with integrity, so that my thoughts and feelings and actions are all in harmony with each other. And I feel right with myself.

- Meanwhile, it’s important to make sure that I am being transparent about my choices in the world–because it’s not enough for me personally to just do the thing. If I don’t voice the value I’m living into, people may see what I’m doing but not understand why. We have a responsibility to bring people along.

“We are scootin’ toward the interdependent stewardship of wellness” -Aaron Spriggs

- Governance is about the big ‘we’. When we understand we as ‘all of us together,’ we consider the moves we make–and the way we impact each other–differently

- Governance is stewardship; it’s caring for the collective navigation of our beingness.

- Our decision making together brings in every part of us, and all of the ecosystems around us into how we’re making every single choice, how we’re moving through our days.

“I am honoring and orienting towards wellness and nourishment–and I practice that in how I speak internally to myself, how I choose to speak in a shared place, how I choose to navigate things like making food in my kitchen–all the choices I make that are interconnected with other people, that impact me and the people around me are all part of that building out into the world we want to live in.”

-Reese Hart

Collective governance is a discipline we choose, so that all people may experience dignity

- We are building strategies to prevent future harm while also taking time to imagine what governance looks like outside of the current structure we live in, that continues to cause harm

- To govern, you need to think about what breaks your heart. And also what you love–and that’s going to help you be who you are in the world. — Rose Elizondo

Governance is a lifelong journey

- Just as in nature’s rhythm of seasons, we are renewing ourselves constantly–our needs are not the same, moment to moment; our bodies are not asking for the same things

- Being able to be open and responsive in the natural ebbs and flows is part of governance practice–it is an ongoing journey of renewal and growth

Governance is the restoration of birthright

- All of us are part of a lineage–we are coming back into ourselves and our humanity, choosing and creating the life we want to live, with the people and beings we want to be with. Almost like we are revisiting our childhoods and getting to raise ourselves–we are deciding who we are, who we want to be, and how we want to relate to (and with) others. How we want to be seen.

- And the capacity for this is something we’re all born with–we don’t have to achieve or acquire; our capacity for governance is already within us. And the more we can see that, the less alone we feel.

“This enormous world I’m part of is always going to be big enough for whatever I evolve into.” -Yesenia Veamatahau

The stance, self care, investment, and spaciousness to be present to what’s happening around us. To step into the choices, in each moment, that enable us to live our values, we need to be present to connections, community, and portals–like the land. Land connects us to today, tomorrow, yesterday. We need to breathe into compassion, boundaries, and love.

We are learning to really be with ourselves–and witnessing the ripple effect that has on others.

Collective governance is rooted in Indigenous peacemaking and restorative justice practices, incorporating laws of nature and spirit.

Forrest Landry says that love is that which enables choice. And perhaps the same is true for governance that Dr. Cornel West says about justice–that it’s what love looks like in public. Governance is ultimately a collective practice–one we are delving into in times of deep uncertainty, isolation, and struggle. We are building when we need to most, the kind of governance we know is possible. Beginning with the choices we make today.

* * *

The reflections in this post were shared during the first gathering of the WeGovern Learning Community Phase 2. Just as the governance we practice, this discussion was a collective endeavor. Deep gratitude to all participants for their presence and contributions: Benjamin Carr, Reese Hart, Monique Tu Ngúyen, Crystal Harris, Ed Heisler, Sarah Curtiss, Leta Harris Neustaedter, Aaron Spriggs, Judith LeBlanc, Lonnie Provost, Brittany Eltringham, Heidi Notario, David Hsu, Adriana Contreras, Estefania Mondragon, Jenni Rangel, Ruby Mendez-Mota, Jovida Ross, Shizue Roche Adachi, Alexis Flanagan, Aparna Shah, Doris Dupuy, Kassamira Carter-Howard, Megan Shimbiro, Yesenia Veamatahau, Karen Tronsgard-Scott, Anne Smith, and LaToria White.

originally published at The Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Coaching for Awareness-Based Systems Change

In the fall of 2019, a few of the founders of the Illuminate network (including CoCreative, Garfield Foundation, McConnell Foundation, and Academy for Systems Change) collaboratively hosted a gathering of systems change “capacity-builders” who work as independent consultants or in small collectives as facilitators and advisors, from the US, Canada, Mexico, UK, EU, and First Nations. This was the first time these practitioners had been invited to meet together with peers to share their perspectives on the state of the field. The North American contingent of the group continued on through the upheavals of the pandemic, meeting virtually in 2020 and 2021 to explore themes of equity and integrating health and healing into systems change practice, as well as launching a pilot pairing senior and emerging practitioners to explore what systems-centric approach to leadership coaching might look like.

CLICK HERE to learn more about this unique systems coaching pilot or visit the Network Weaver resource page to download the full article.

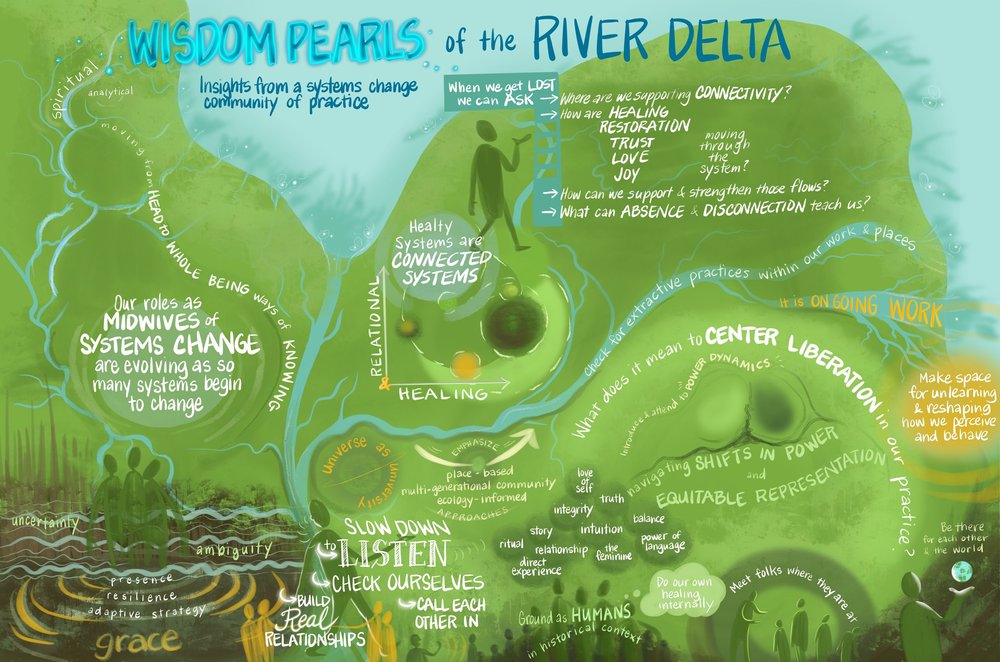

Check out the infographic below for some of the key insights from their COVID-era dialogues on the state of the field of systems change.

Learn more about the wisdom pearls HERE

You can also download a pdf with a link to this information to save to your personal library by visiting the Network Weaver Resource Page.

Katy Mamen is passionate about participatory change-making approaches that account for the complexity of multiple, interconnectedness crises and diverse lived experiences. She brings thoughtful and committed partnership to social sector clients advancing transformative systems change, drawing on expertise in social change strategy, facilitation and group process, systems theory, collaborative networks, and organizational development. In addition to process expertise, her work is informed by a strong background in economic justice, food & farming, water issues, and rural equity.

Brooking Gatewood helps leaders and groups clarify and enact the change they want in themselves, in their workplace, and in our shared world. At heart, her work is about co-liberation from systems of ‘power over’ and moving toward systems of ‘power with’ that honor individual agency as well as collective interests and wisdom. In practice, her coaching and consulting focuses on transformation across levels - from individual and team mindsets and behaviors to large-scale policy and systems change.

Originally published at IlluminateSystems.org

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

On Collective Liberation and Natural Networks: an Interview with LLC’s Nikki Dinh and Ericka Stallings