For years in conversations in organizations, within advocacy groups, and social change initiatives, I have heard variations of these themes:

- “We know we have to move beyond top-down approaches – how do we get more bottom up input and ideas?”

- “How do we get more diverse voices to the table? We need the input of the grassroots in the room.”

- “How do you engage the people on the ground with lived experience?”

Notice the images within these statements: they imply a vertical hierarchy where there is a top and bottom (e.g., grassroots, on the ground). Hierarchical thinking is so ingrained in our mindsets and how our organizations are set up that it can be hard to imagine another way. Yet, these vertical images are a conceptual overlay on reality. In Donella Meadows’ landmark article Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in System, she described 12 ways to intervene in a system, in increasing order of effectiveness, starting with #12 as the least. Near the top, #2 on her list is: The mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises. She writes: “The shared idea in the minds of society, the great big unstated assumptions—un-stated because unnecessary to state; everyone already knows them—constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works.” #1 is: The power to transcend paradigms.

What happens when we choose different orienting metaphors? I recently had the opportunity to be part of a global learning gathering in Sierra Leone to see first hand a change initiative that intentionally uses specific metaphors and images to orient its work. Seeing these alternatives helped me discover what is possible when we create structures that arise and work from a different paradigm.

Sierra Leone is in West Africa, a country of six million people that endured a brutal civil war. John Caulker was a human rights advocate in Sierra Leone who was involved with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) after the war. In addition to the TRC, Sierra Leone had a Special Court, a hybrid national/international judicial process that indicted 13 people for war crimes. He saw a need for reconciliation work to mend the broken bonds of community – at the community level. John met Libby Hoffman, a US funder with Catalyst for Peace, who had a similar interest in supporting community-level healing and development in a systemic and sustained way. They created a partnership that has worked together for 12 years through a non-profit in Sierra Leone called Fambul Tok, which means ‘family talk.’

Inside-Out Peacebuilding and Development

As a country that had been colonized and then was subjected to aid and development initiatives sent in from the outside or “rolled down” from government, aid agencies, and non-profits, the communities in Sierra Leone had rarely been asked what they needed. To explain how this method of providing aid was actually not helpful, Fambul Tok and Catalyst for Peace developed a new metaphor, as Libby shared at our gathering:

“Imagine a community as like a bowl. Humanitarian aid, whether for peacebuilding, health, education, economic development or any other purpose is like a bottle of water. When there is a crisis, resources get poured into the bowl — but they just go right through. The bowl is cracked. And if you keep pouring water into a cracked container, it widens the cracks and can damage it further — while also depleting the supply of water. Not a healthy cycle for anyone. The community container itself is invisible in the system, and the work of repairing the cracks completely absent. An inside-out approach to peace is not about pouring water into a community. The work is about repairing the container. When the cracks in the bowl are fixed — when a community is healed and whole — it holds water, and the community’s own resources flow over.”

They call this “inside out peace and development.” Fambul Tok’s process was to “go to” and “walk with” communities, listening and building their capacity to plan and implement their own reconciliation and then development programs. The outsider’s role is to encourage, hold space, and accompany, not direct. Forgiving the Unforgiveable is a TED talk by Libby that shares the story of their early work. On Fambul Tok’s web site, they highlight their underlying philosophy: “Our approach is rooted not in western concepts of crime and punishment but in communal African sensibilities that emphasize the need for communities to be whole – with each and every member playing a role.” I encourage you to watch this film about the reconciliation phase of the work.

At the learning gathering I attended, they hosted 100 people from 15 countries for a five-day event, which included visiting villages to see first-hand how the work and spirit had taken root over 12 years. We divided into groups and each group visited one of ten different communities. Each group experienced an unbelievable welcome with singing, dancing and drumming, and warm hospitality. We sat in on their community meetings, led by women’s groups called Peace Mothers that use micro-enterprises to pool resources and generate more wealth with their own local resources. Some began community farm enterprises, while others are doing soap-making. There was a quality of ownership, locally-led initiative, and collaboration toward a shared purpose that moved us all. And there was a real sense of dignity. People spoke of the “mended cup” and said “we are united.”

One of the participants who visited a village said, “I saw the power of metaphor —the way the community explained to us what they are doing was through the story of the broken cup. If you can find a way to explain what you’re doing that is simple and powerful, I saw how extraordinary that can be.”

In communities across the country, they discovered that when the focus and supports were there to allow local people to ensure the “cup was mended,” there was a release of initiative, energy, and resources. The reconciliation work was a foundation that then evolved into vehicles for people-led economic and community development, women’s leadership, and an inclusive people-led planning and governance process. That local planning process is now being adopted nationally in a new framework for inclusive governance and rural planning.

Outside-In vs. Inside Out Approach

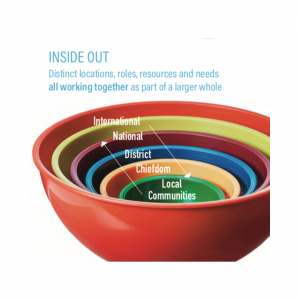

A related visual metaphor helps everyone to see how parts of a system can work in ways that encourage health and responsiveness at each level. In an “outside in” approach, aid and direction are separate and not coordinated/driven by the target community.

This report provides an excellent summary of the philosophy and partnership: Building Peace from the Inside Out In it, Libby writes: “In a system that is whole, the varied levels of aid and support are not fragmented and separate from each other and from the target community (an outside-in system), but rather are nested all together as parts of a larger, interconnected whole. Each level is its own bowl—a ‘container’ that holds the highest purpose and potential of that sector or level.

The role of the bowl within (the ‘insider’) is to draw together in honest conversation with peers about needs, goals, challenges, desires, even when that means having ‘frank talk’ about difficult things; to name and claim their own agenda, and to work togeth

er to achieve it.

The role of an external ‘bowl’ (the ‘outsider’) is to hold the space to see, invite and magnify the voice, leadership and capacity of the level within.”

These two metaphors of mending the cup and nested systems can be adopted in many places. For example, in education, how do we shift to seeing a classroom at the center, with the quality and health of that experience being the focus, and other parts of the system supporting that? This view of nested systems is how nature works, and is a similar model emerging in businesses using self-organizing teams, in networked collaborations, and in regenerative design approaches.

For those ready to transcend paradigms of top-down/bottom up ways of working, the model and example of what has emerged in Sierra Leone is an inspiring example to learn from. They are living a new way:

“We are not trying to change the system as if peace and development is something ‘out there.’ We want to live into the system the way we think it should be.”– Libby Hoffman

Originally published at New Directives Collaborative on May 4, 2019.

Photo by NordWood Themes on Unsplash