Network Strategies For Your Network

The following video is about 20 minutes long and provides a short overview of network strategies. It was done for the Food Policy Network State Networks, who graciously agreed to let me share it.

The video emphasizes the importance of being part of networks of networks and of catalyzing self-organizing to move us to a more experimental, learning and viral space. Increasingly I’m seeing networks of networks and self-organizing as the key factors needed to shift systems.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="30px"]

Designing Meetings that Do More

Imagine leaving a meeting feeling naturally inspired, energized by new ideas, with enhanced goodwill toward your colleagues, and a shared sense of alignment and clarity for where to go next. In a highly-functioning group, ideas and experiences cross-pollinate, perspectives broaden, assumptions shift, and something new emerges that no one could have discovered alone. Sadly, many people spend a lot of time in meetings, which are boring, routine, frustrating, and do not access the ideas and perspectives of every one in the room.

Here are some of the needs I often hear expressed by people in organizations and those working on positive social change:

- Our work is to ‘siloed’ – people are not aware of what others are doing.

- Insights or lessons learned are not well communicated so others make the same mistakes or reinvent the wheel

- We spent all this time to come up with a plan and now that we are rolling it out, people are resisting and objecting to it – we need better messaging.

- How do we convince people to act? To change? To adopt our goals?

In a world of pressing demands and complex challenges, where people want to have impact, take action, and get outcomes, what gets overlooked is the process of how we get there. The how is all about how people are engaged, brought together in meetings, and how they participate, learn, and think and work together. As Atul Guwande, a surgeon and writer says, “Human interaction is the key force in overcoming resistance and speeding change.”

In over 25 years of work in organizations and collaborative initiatives focused on environmental and social change, I have come to realize that meetings hold more potential than we typically access. I have been blessed to discover some great teachers and had the opportunity to learn, experience and practice new ways of working and organizing meetings to achieve multiple benefits (see end of this blog for credits.) We can design meetings to do more.

Design starts with intent, which means becoming aware of the world view and assumptions that inform our choices. I’ve always been inspired by how one quote or question can shed light on and shift my assumptions and intentions. Here I’d like to share the quotes that inspire how I design meetings:

“Are you lighting a candle or filling a bucket?”

There is a tendency to highly script every minute and fill a meeting or workshop with speakers and presentations, squeezing in a bit of Q&A with the participants. If our aim is to spark people’s motivation, willingness to engage and take action, getting the balance right of presentations with conversation is key.

“It’s a far superior strategy to get all the minds working on what needs to change, rather than to convince each person to do what we think is best.” -Fran Peavey

Inviting a group to consider well-framed strategic questions is a great the way to get all minds working on what needs to change. This engagement, when well designed, is what leads to better thinking overall and an experience of participation and contribution. When people help shape a strategy or plan, there is less need for “messaging” and convincing.

“Nothing about us without us.”

This slogan from South African disability activists is a good reminder to have people in the conversation who are closest to the situations being discussed. Aryanna Pressley, who is the running for Congress from Massachusetts, said it well: “The people closest to the pain should be closest to the power.”

“If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask, for once I know the proper question, I could solve the problem in less than five minutes.” - Albert Einstein

An effective practice for meeting design is to have a design team work ahead of time to consider and distill the most important relevant questions to be considered by the group. As this blog shares, this strategic clarity and investment before the meeting “sets the table” for productive conversations.

“Social learning networks enable better and faster knowledge feedback loops, essential for innovation and creativity…social learning is how we share implicit knowledge and get work done.” – Harold Jarche

Combining a good question with meeting methods that get people talking in small groups and then mixing and cross-pollinating those conversations enables us to access the ‘collective intelligence’ of a group. Methods such as World Café, 1-2-4-All, and Open Space allow many voices to be heard and inform the group’s understanding and development of consensus, as I have written about in other blogs.

On October 11th, I will be hosting a workshop called Designing Meetings that Do More, which will explore more of these ideas. Hope you will join us!

Credits go to (among others):

Art of Hosting, Liberating Structures, World Café, Fran Peavey and strategic questions, Tom Atlee and the Co-Intelligence Institute, Harold Jarche, Time to Think, National Council on Dialogue and Deliberation.

Originally published on October 3, 2018 at New Directions Collaborative

Trust In Networks

Trust in networks is different than trust in organizations or coalitions where it is essential to spend time building trust among everyone because the relationships are likely to be long-term.

However, networks often have hundreds or even thousands of participants and it is not possible for everyone to know everyone else in the network, let alone have the time to build deep relationships. People in self-organizing networks are often involved in a number of collaborative projects at any one time, but these projects are often of short duration with little time to build deep trust, and after the end of the project they may not work with those individuals again.

For this reason, people in networks need to learn how to build swift trust. Swift trust, explored by Debra Meyerson and colleagues, means that the participants of a collaborative project interact as if trust were present.

Several things make establishing swift trust easier. First, when a few of the collaborators have had previous experience working together, they can set the tone or standard of trustworthiness that others buy into. For example, they can model openness, appreciation and other qualities that help everyone be more trustworthy.

Another key to swift trust is the communications ecosystem and values. By agreeing to be transparent and make all their work easy to observe and be accessed by others, it’s easy for all participants to see that others are doing the work they said they would do. That’s why it’s so important to use tools like google docs and set up task and timeline spreadsheets, a place for meeting notes and a budget and expense spreadsheet. Slack is another tool that helps people see what others are doing.

Another essential ingredient of swift trust is taking time to clarify roles in the project based on specific expertise. For example, I am in a collaborative project where one person is responsible for developing content, another for the tech aspects of the virtual sessions, and other for the communications. This doesn’t mean that each person does all the work in their area - in fact, we often work together on content - but one person is responsible for moving that part forward. The clearer the roles are to everyone, the less conflict is likely to occur.

As in any situation, it’s always important to take time to help people know each other: even if the group is working virtually, it’s easy to set up breakout rooms in zoom.us where smaller groups or dyads can share about themselves. If the project has a convener, it’s helpful for them to state values such as “We are all unique, and each of us has quirks or things about ourselves that can affect our work. For example, one person has a child with a chronic illness; another person may be very introverted. We need to get to know people so that we know about these things and realize the parent may be called away from work to care for the child and we need to make sure the introverted person has space to talk.”

Having skills in dealing with a person when they do not do what they have agreed to do is essential. People quickly become more reliable if small infractions are dealt with immediately and directly (often through a one on one conversation).

If someone proves to be difficult to work with or untrustworthy, they will find that they are not included in future network collaborations. This is a powerful incentive for most people to contribute as positively as they can. Word of mouth that occurs in the network means that effective contributors will find they are frequently sought after for projects.

Undergirding swift trust is a set of network values and understandings - things such as openness, transparency, acceptance of difference. Network weavers can help ensure that most network participants are aware of these values.

On Friday we will offer a free Trust Assessment that network weavers can use to increase network participants awareness of these critical elements of trust. [ap_spacing spacing_height="30px"]

How To Increase Participation Through Increased Engagement

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

A new free resource is available in the Resources section of Network Weaver.

Many people ask me "How do I get people to participate more in our network?" This simple worksheet offers tips that you can quickly implement to get network participants interacting with each other. We have found that is one of the best strategies for getting them to invest more time in the network.[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

Many people ask me "How do I get people to participate more in our network?" This simple worksheet offers tips that you can quickly implement to get network participants interacting with each other. We have found that is one of the best strategies for getting them to invest more time in the network.[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]Freeing Up Your Time for Transformation

As was mentioned in Monday's post, the sense of urgency is a major impediment keeping our networks from being transformative. I'd add busyness to that: having endless to do lists that keep us stressed and leave no time for the kind of deep reflection and learning that we need to really make progress on the complex problems we are trying to solve.

Find this worksheet on the Resources page: HERE

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

Self-Organizing Toolkit

A new free resource is available in the Resources section of Network Weaver.

The self-organizing toolkit includes a set of simple actions that you can take to jump start self-organizing in your organization or network.

It includes a clustering activity for meetings to help people find others interested in the same or similar activities and surveys that can be used to help people cluster. In addition, it detailed the three roles that you can take to support self-organizing by being a project coach, setting up a communications system, and setting up a community of practice for projects.

The toolkit also includes sample google docs and spreadsheets that you can use so that projects can stay on track. Finally, the toolkit discusses how to set up an Innovation or Seed Fund to provide financial incentives to self-organized projects.

What Is Self Organizing?

Self-organizing is perhaps the most important and least understood aspect of System Shifting Networks.

There are many scientific definitions of self-organizing but they are hard to wade through. After 20 years of helping networks self-organize, I’ve created a definition that is very concrete and practical for getting started with self-organizing.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Self-organizing happens when any individual or group...[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- sees an opportunity to make a change or try something out (idea or opportunity isn’t dictated by anyone else)[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- feels like they can initiate action (self-generated idea and action)[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- finds diverse others from a large network to join with them or collaborate (those who work on the project aren’t dictated by anyone else, people self-select to participate)[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- experiments with small actions[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- accesses the (usually small) resources they need to act[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- spends a lot of time paying attention to what is happening, debriefing, learning from the experience, and analyzing what they did -- all to enable them to take a better next step[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- shares what is learned with the larger network [ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

A self-organized project has an end - when it ends, all the participants can decide if they want to work with others on their next project or not.

Self-organizing becomes transformative when there are thousands of such projects in a network, and each individual is involved in a number of projects, so that innovations and new ways of looking at problems spread rapidly throughout the network, enabling each new project to be more effective. The spread of the use of zoom.us videoconferencing platform by networks over the last two years is an example of how innovations can spread from project to project virally.

Self-organizing is based on the assumption that we don’t know how to solve most of the problems we are trying to solve. Self-organized projects probe the problem, helping us learn more about it and how to best shift the system that is generating the problem.

Another transformative aspect of self-organizing occurs when participants in self-organized projects come together in communities of practice to share what they have learned from their project, support each other with challenges, and discuss how they can apply what they have learned to future projects. When this is shared with the larger network everyone can benefit.

Here is an excellent video of Tamara Shapiro of Movement Netlab on a Leadership Learning Community (LLC) webinar on Self-organizing in Occupy Sandy. Highly recommended!

Friday, Network Weaver will be posting the Self-organizing Toolkit, which you will be able to download for free in the resources section.

In the coming weeks we will outline the simple steps you can take to jumpstart self-organizing in your network.

How have you experimented with self-organizing in your networks? Please share in the comments section below.

June Holley

Foodshed team learns how to establish consent instead of consensus

In Propositions for Organizing with Complexity: Learnings from the Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP), Nikki D’Adamo-Damery described nine propositions that emerged from the work of the AFP. Proposition #2 was: “Establish Consent instead of Consensus.” The following story describes one of the experiences we had together, when Tracy was facilitating the management team, that led to this proposition.

This story begins when the AFP management team was making decisions about how they were going to award mini-grants to on-the-ground projects that addressed community food security. The team included the principal investigators, graduate students, extension agents, and representatives from community-based organizations, and so reflected some of the diversity of the system within which they were working. The team was using a collaborative decision-making framework, and the basis for decisions was the principle of consent.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

The principle of consent

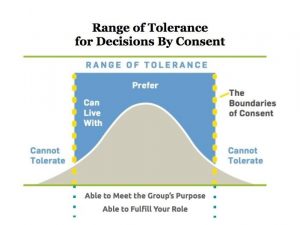

People often think there are only two choices for how we make governance decisions: by majority or consensus. Most people fail to realize that decision-makers have a third option – decision-making by consent – that can be preferable to either of these for governance decisions. The Consent Principle means that a decision has been made when no member of the group has a significant objection to it, or when no one can identify a risk the group cannot afford to take. In other words, the proposal is not out of their Range of Tolerance (see below). Those risks are things that would undermine the purpose, or that would create conditions that would make it very difficult for a member to perform his or her role.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

The test for the management team

The urgency to get the funds out into the field put pressure on the team to make a decision. On the one hand, there was clear value in having these different perspectives at the table as they discussed funding priorities and how to make the application process more accessible. On the other hand, there were conflicting opinions when it came to designing the application. Was it ethical for representatives from community agencies who might apply for the grant funds, to design the actual application? A professor said “no” and a community agency rep said “yes.” There were concerns that the difference of opinion might limit progress.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Consent is grounded in dialogue, not debate

It was through this experience that they learned that, by using consent as the basis for decisions, the team did not have to agree. Instead of debating, they inquired into what was out of the range of tolerance for each of them. They listened to each other’s objections as feedback about potential risks so they could adjust the solution to mitigate those deemed unacceptable.

Here’s what they discovered:

- The professor was actually concerned that there might be a perception about a conflict of interest if the community partners applying for awards were involved in the design of the application questions. That perception was the risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the project’s credibility and trust in the community.

- The non-profit director was concerned about the integrity of inviting community reps into the decision-making process, and then withholding that power when issues got sticky. That power dynamic was a risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the trust within the core team.

Once they discerned the reasons for concern – and chose to respect what was important to each of them – they found a way forward. The decision was to include the community partners in decisions about the application design, as full decision-makers, AND to be fully transparent in all public communications about their participation. As a side note, they were simultaneously clear that, if one of those community-based organizations applied for a grant, they would recuse themselves in the selection of grant recipients.

The grant application design and process went mostly smoothly with no conflict of interest issues. The second round of distribution of mini-grants moved even more quickly, building on the trust that had been built the first time around.

This blog post originally ran on the Virginia Cooperative Extension: Community, Local, and Regional Food Systems blog. and at CircleForward.us

*The Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP) originated in 2011 as a grant funded through the USDA’s Agriculture, Food and Research Initiative (AFRI) grants program (Award Number: 2011-68004-30079). Virginia Tech served as the lead academic institution in partnership with North Carolina State University and West Virginia University for a five-year endeavor to address community food security in western North Carolina, southwest Virginia, and West Virginia.

By Tracy Kunkler, MS – Social Work, professional facilitator, planning consultant, and principal at http://www.circleforward.us/[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Please post any thoughts, comments or stories in the comments section below.

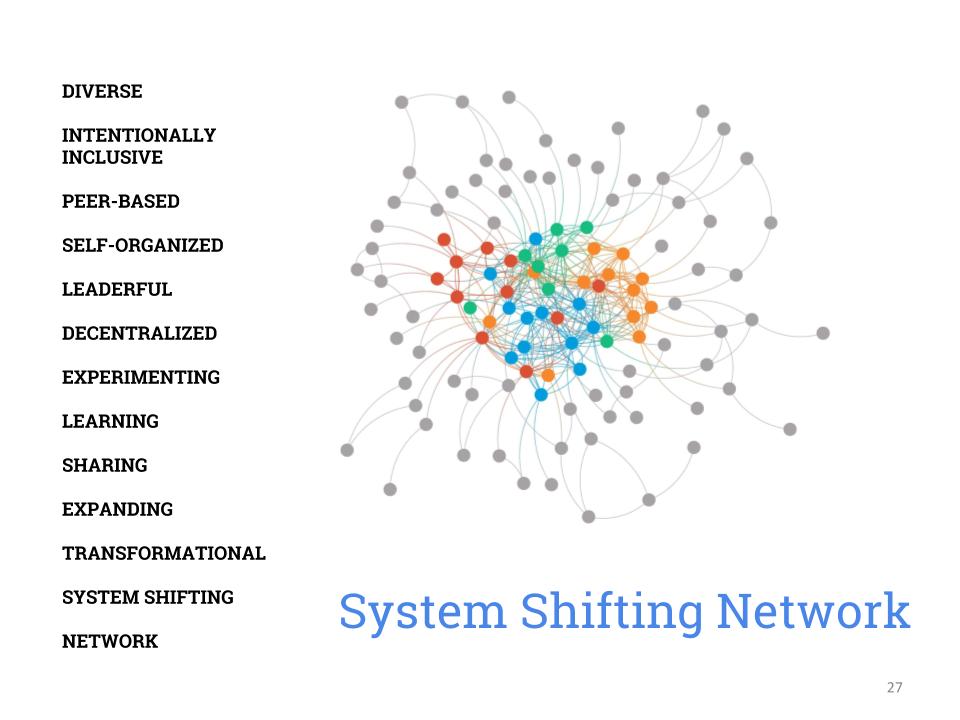

System Shifting Networks

Not all networks are the same! If you are interested in transforming systems so that they are good for everyone, then you are probably helping people co-create a System Shifting Network.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]If you are not familiar with network maps, here is a short guide: [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The circles represent individuals.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The colors represent diversity - you can make maps that show geography, type of organization the individual is part of, race/ethnicity, interests, etc.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The lines represent relationships. You can draw maps where the lines represent different relationships: that the individuals know each other, have worked with each other, or want to work with each other.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The network has a substantial core or center of diverse individuals who know each other or are only a few steps away from others.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The grey dots represent people in the periphery, that is, only one or two people know that individual. People in the periphery are often resource people that can be drawn on as needed, or people from other networks. The periphery should have 3-5 times the number of people in the core.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Here’s what makes a System Shifting Network more powerful in creating change than most types of networks. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Groups of people in System Shifting Networks (SSN's) are continually forming new collaborations to try to learn more about the system they are disrupting and the system they are shifting to. Often SSNs have dozens or even hundreds of these collaborative projects underway at any one time, and many people are in more than one project. Because of this overlap, innovations generated in one collaboration often quickly spread to many other collaborations. Think, for example, about the way the use of zoom.us videoconferencing has spread among people in networks.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- People in System Shifting Networks are continually bringing new people, especially those often under-represented, into their collaborations. These individuals often bring in new perspectives and make people challenge their assumptions, often resulting in much more effective projects.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- In these collaborative projects, people have to scramble to develop new skills and learn new ways of working together. People in these collaboratives work as peers, even though they may identify a coordinator. Everyone in the project learns how to organize and implement a project, and thus there are plenty of new network leaders capable to initiate new projects. So leadership is continually expanding. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Projects are seen as experiments - a way to get more insight into the system they are shifting. They learn what works and do more of it.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- People in projects take time to share what they are learning with others in the network and in other networks so that everyone benefits from every project, whether it was a “failure” or a success.

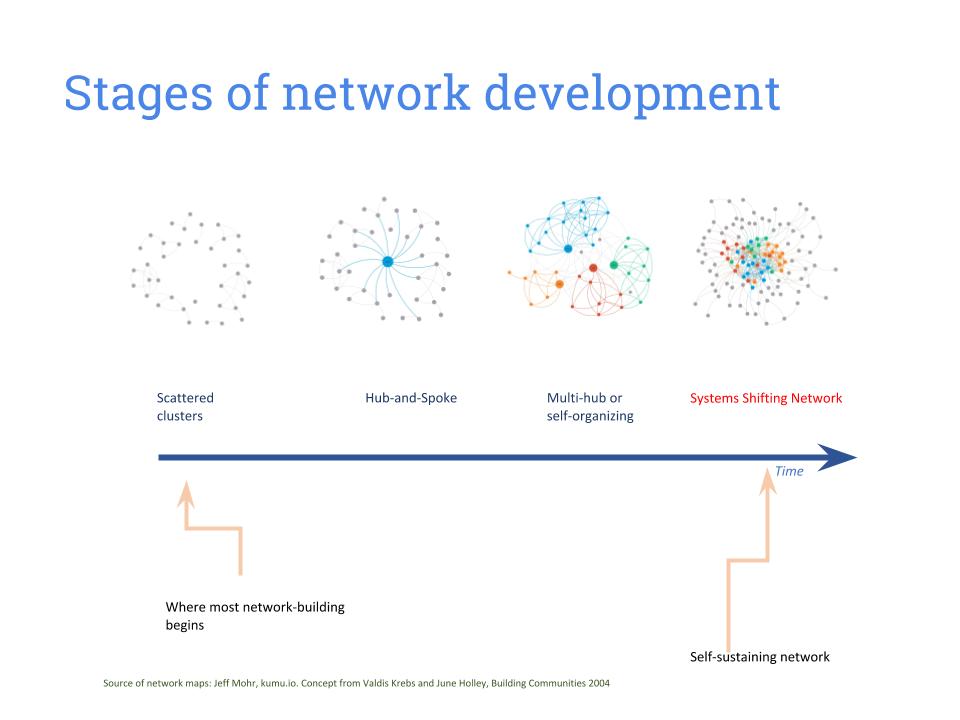

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]But how do we develop System Shifting Networks? Most networks go through 4 stages: [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

STAGE 1: Many networks start as scattered clusters among individuals. Often the relationships in these clusters are informal - people talk to each other in the grocery store and at their child’s soccer game .[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

STAGE 2: Then some individual, organization or group decides to start the formation of an intentional network focused on a particular issue, problem, sector or geography. They become a network hub. They reach out to others they know are interested in the issue and find out about their needs and interests. Often networks stay in this stage, and the hub broadcasts useful information to the interested individuals and has conferences and webinars so network participants can gain new information. However, if a network stays at this stage it loses many of the advantages of networks and will not be capable of changing a system.

STAGE 3: The next stage moves the network to a self-organizing phase. With a lot of support (which we will go into in detail about in future blog posts), individuals or groups in the network start noticing some action that might make a difference and form a collaborative project. Sometimes a network does a system analysis and identifies leverage points and forms working groups to generate experiments in that area. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

STAGE 4: The final stage - a System Shifting Network - emerges when a substantial support structure - communications, learning, restructured money and resources and just-in-time tracking shared with participants - is developed. Projects get larger and have more impact.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]What stage is your network? Please share in the comments section below.

Starting a Self-Organizing Learning Group to Write a Book

It's bothered me for a long time that very few folks in the non-profit sector produce practical materials that others can easily adopt or adapt. I'm a prime example of that. I've been trying to write a book about self-organizing for two years, and haven't made much progress because I’ve been too busy doing the work. But recently I had an interesting thought. Why not model a process for writing a book that embodies the principles of self-organizing, and forces me to integrate reading, thinking and writing about self-organizing into my already crammed schedule?

So first I found someone to help keep the process going --- Susan Rossetti. Besides being a great writer, she’s smart, interested in the subject, and someone who would make a great partner in this emergent process. Together we decided to act on a suggestion from Gigi Barsoum that we start a learning cluster on self-organizing. Not only would the learning-cluster keep us accountable, but as Steven Johnson suggests in his book and TedTalk, “Where Good Ideas Come From,” the collective wisdom and thinking of the learning cluster would be much more likely to yield new, truly innovative ideas about self-organizing than anything I could generate myself.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]How does our learning cluster work?

First, we set up a Google Docs folder that includes the group’s contact list and two working documents: an annotated bibliography, and a document for the group to capture its research and musings on the definition and fundamental characteristics of self-organizing. Susan and I “pre-seeded” both documents, and in the annotated bibliography we included additional columns so the group can track who is reading what, add topic tags and hot links to original sources, and rate the relevance and quality of each reference.

Next we used Doodle to schedule our first video conference, and sent out a short survey using Google Forms to the group to find out what their interests are in participating.

Last week we held our first video conference using Adobe Connect. During the session, we outlined how the learning cluster will work, how we will communicate with each other and share back the learnings from the cluster (what we call our “communications ecosystem”), and we presented our working definition of self-organizing.

In future sessions, members of the group will take turns presenting their findings from their research, and together, we’ll develop an accessible conceptual framework for self-organizing, and identify and test tools and practices that we will share with the field. Be sure to stay tuned as we begin this journey of discovery together!

What has been your experience with learning groups? What can we learn from your experience? Do you know of anyone else trying to write a book this way?