Communication Ecosystem

A new downloadable free item is up on the Network Weaver Resources page.[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

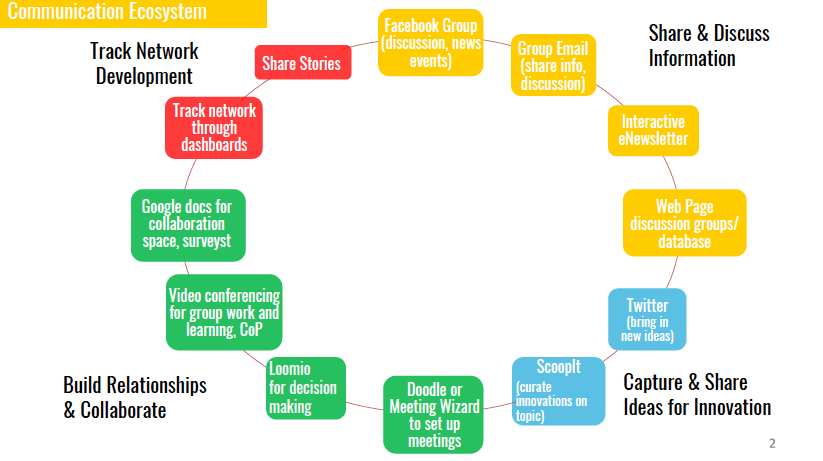

One of the most critical support structures for networks is a well-thought out communications ecosystem - a set of tools and platforms that enable everyone in the network to connect and collaborate directly with anyone else in the network.

This kind of communication system is quite different from the broadcast strategy of many organizations, where the organization sends out information via a newsletter and/or website but has no avenues for people to respond or build connections to each other.

A communication system that supports interaction among network participants needs to fill four functions:

- Provide spaces and places for discussing ideas and for sharing what has been learned. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Ensure that everyone has access to new ideas and innovations from other communities and networks.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Many places for network participants to get to know each other and deepen relationships, and to work together collaboratively.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Ways to track network development (network leadership, network values, collaboration and collaborative skills, stages of network development, development of network support structures, network stories, etc) and use this data to enable the network to move more rapidly to a system shifting networks. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]You can use the free handout in the Resources section to engage participants in your network in a process to help co-design your network's communication ecosystem. Share the handout with any network participants who are interested and begin to fill out the page with blank boxes

NENAD MALJKOVIC

CLICK HERE to download Communication Ecosystem handout.

Three Ways To Foster Education On Complexity Using Network Visualizations

There should be more focus on systems thinking in education, Roland Kupers argues convincingly in the Global Search for Education on the Huffington Post. As complexity always involves interconnectedness between components, I find network visualization particularly useful in my educational practice.

- It creates systemic awareness, because users are forced to think about interrelationships: linear versus non-linear relations; coping with uncertainty; etc.

- It counterbalances the urge to automatically take the reductionistic approach to problems and issues. In other words: next to analysis –quite literally: taking apart to study the components- it makes room for synthesis –zooming out to the constellation on the system level.

- It provides a kickstart for introducing key concepts in a non-technical way.

- It fosters dialogue between students, pupils or stakeholders.

Here, I provide three ways I find promising to explore further.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]1. Promote Network Literacy in primary, secondary and tertiary education simultaneously

I am grateful to the NetSciEd-initiative for having coined the term Network Literacy, to promote the use of network science concepts in primary and secondary education. This could involve the creation of conceptual network visuals, drawn by hand. It could also entail creating more formal networks made with datasets and software.

I am convinced this is an excellent way to build on young people’s innate capacities of exploration, wonder, creativity and sense of interconnectedness.

However, I think it will take some effort to create leverage with teachers in our present day educational system. As Kupers points out, this system is characterized by high degrees of path dependency, with a firm basin of attraction in the reductionistic tradition. From my experience with education in the Netherlands, I agree with him. Therefore, I would also suggest promoting Network Literacy in tertiary educational curricula, to teach the teacher.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]2. Use network visualization to integrate Network Literacy with 21st Century Skills in curricula

I see 21st Century Skills like creativity, critical thinking and effective cooperation getting more and more popular in designing new educational curricula. Through my experiments with network visualizations I discovered that they can help both students and professionals to work on these skills.

I experimented with network visuals in professional education settings, e.g. with journalists and journalism students. This ‘Systemic journalism’ enabled them to create more angles and story ideas, fostered their willingness to share knowledge and enhanced a more future-oriented perspective.

Imagine a class of journalism students, each researching municipal financial policy in relation to construction projects.

In drawing network visuals of interconnected stakeholders, they applied creativity and critical thinking skills. In presenting and discussing their visuals, they tested basic network literacy skills as well as communication and problem solving skills.

Kupers asks, “How can a student pose a question in a physics class, based on an insight gained in a poetry class?”. Using some kind of network visualization could help creating a non-technical common complexity language.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]3. To enhance momentum, visualize the process of change in education itself

Kupers says, “the level of change required is both subtle and profound. In keeping with insights on how systems learn and change, it appears best to experiment widely, connecting and building on pockets of progress.”

Identifying key innovators, hubs and other players in the educational network, and visualizing their interconnectedness can have a profound impact on the pace of change.

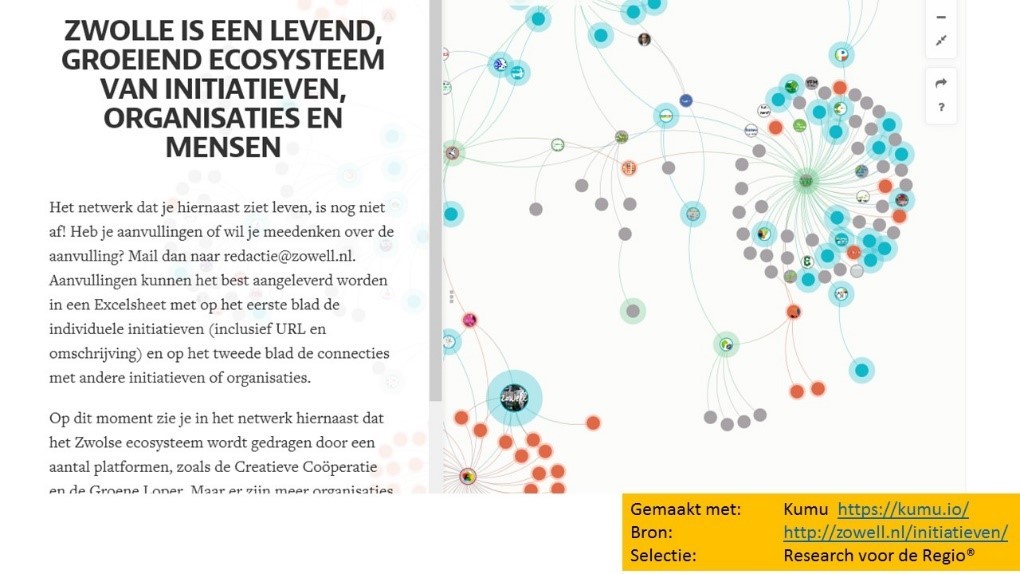

In a similar context, I helped setting up an interactive graphic depicting a ‘city ecosystem of social initiatives’. Using software from Kumu, an overall view looks like this:

Publishing a network visual like this not only helps spreading knowledge, but also triggers people to (inter)act.

Further exploring these three paths to me looks like a promising strategy.

"The task of knowing is to swim in the complex" -David Weinberger

Originally published May 16, 2016 on LinkedIn

Foodshed team learns how to establish consent instead of consensus

In Propositions for Organizing with Complexity: Learnings from the Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP), Nikki D’Adamo-Damery described nine propositions that emerged from the work of the AFP. Proposition #2 was: “Establish Consent instead of Consensus.” The following story describes one of the experiences we had together, when Tracy was facilitating the management team, that led to this proposition.

This story begins when the AFP management team was making decisions about how they were going to award mini-grants to on-the-ground projects that addressed community food security. The team included the principal investigators, graduate students, extension agents, and representatives from community-based organizations, and so reflected some of the diversity of the system within which they were working. The team was using a collaborative decision-making framework, and the basis for decisions was the principle of consent.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

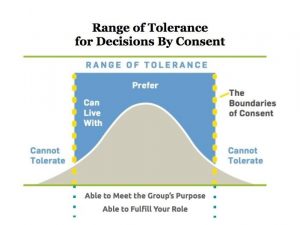

The principle of consent

People often think there are only two choices for how we make governance decisions: by majority or consensus. Most people fail to realize that decision-makers have a third option – decision-making by consent – that can be preferable to either of these for governance decisions. The Consent Principle means that a decision has been made when no member of the group has a significant objection to it, or when no one can identify a risk the group cannot afford to take. In other words, the proposal is not out of their Range of Tolerance (see below). Those risks are things that would undermine the purpose, or that would create conditions that would make it very difficult for a member to perform his or her role.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

The test for the management team

The urgency to get the funds out into the field put pressure on the team to make a decision. On the one hand, there was clear value in having these different perspectives at the table as they discussed funding priorities and how to make the application process more accessible. On the other hand, there were conflicting opinions when it came to designing the application. Was it ethical for representatives from community agencies who might apply for the grant funds, to design the actual application? A professor said “no” and a community agency rep said “yes.” There were concerns that the difference of opinion might limit progress.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Consent is grounded in dialogue, not debate

It was through this experience that they learned that, by using consent as the basis for decisions, the team did not have to agree. Instead of debating, they inquired into what was out of the range of tolerance for each of them. They listened to each other’s objections as feedback about potential risks so they could adjust the solution to mitigate those deemed unacceptable.

Here’s what they discovered:

- The professor was actually concerned that there might be a perception about a conflict of interest if the community partners applying for awards were involved in the design of the application questions. That perception was the risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the project’s credibility and trust in the community.

- The non-profit director was concerned about the integrity of inviting community reps into the decision-making process, and then withholding that power when issues got sticky. That power dynamic was a risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the trust within the core team.

Once they discerned the reasons for concern – and chose to respect what was important to each of them – they found a way forward. The decision was to include the community partners in decisions about the application design, as full decision-makers, AND to be fully transparent in all public communications about their participation. As a side note, they were simultaneously clear that, if one of those community-based organizations applied for a grant, they would recuse themselves in the selection of grant recipients.

The grant application design and process went mostly smoothly with no conflict of interest issues. The second round of distribution of mini-grants moved even more quickly, building on the trust that had been built the first time around.

This blog post originally ran on the Virginia Cooperative Extension: Community, Local, and Regional Food Systems blog. and at CircleForward.us

*The Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP) originated in 2011 as a grant funded through the USDA’s Agriculture, Food and Research Initiative (AFRI) grants program (Award Number: 2011-68004-30079). Virginia Tech served as the lead academic institution in partnership with North Carolina State University and West Virginia University for a five-year endeavor to address community food security in western North Carolina, southwest Virginia, and West Virginia.

By Tracy Kunkler, MS – Social Work, professional facilitator, planning consultant, and principal at http://www.circleforward.us/[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Please post any thoughts, comments or stories in the comments section below.

Free Worksheets

We are now offering two network worksheets at no cost.

The first is the Network Weaver Checklist, revised from the NW Handbook version and in an easy to print pdf format. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]This checklist is great to give to people in your network at a face-to-face gathering. Have them spend 5 or so minutes to take the survey. Then have a chart paper (or 2-3 if the group is large). Using a marker, make a line down the center of the the paper and then one horizontally across from side to side. Mark the upper left quadrant with Connector, the upper right quadrant with Facilitator, the lower left quadrant with Project Coordinator, and the final quadrant with Guardian. Then have people put a red dot in the quadrant where they got the most 4s and 5s, and a green dot in the quadrant they would like to learn more about or do more.

Have them pair up with another person and talk about what they learned about themselves as a network weaver and what they would like to learn.

Then have the whole group notice the quadrant(s) where it is strong, and the quadrant(s) where there aren’t many people currently working. Notice which quadrant has lots of green dots - the network may want to do some explicit organizing of training in this are.

To download the Network Weaver Checklist: CLICK HERE

The other free worksheet, Questions for Deep Reflection, is a set of 20 questions that you can use for reflection in your network project follow-up. This list of questions is designed to help you observe what worked and where you might improve.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]To download Question for Deep Reflection: CLICK HERE.

We will be adding new free items each week and will let you know when they are available through our e-newsletter. To sign up for the e-newsletter click on the button below.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]