What Is Self Organizing?

Self-organizing is perhaps the most important and least understood aspect of System Shifting Networks.

There are many scientific definitions of self-organizing but they are hard to wade through. After 20 years of helping networks self-organize, I’ve created a definition that is very concrete and practical for getting started with self-organizing.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Self-organizing happens when any individual or group...[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- sees an opportunity to make a change or try something out (idea or opportunity isn’t dictated by anyone else)[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- feels like they can initiate action (self-generated idea and action)[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- finds diverse others from a large network to join with them or collaborate (those who work on the project aren’t dictated by anyone else, people self-select to participate)[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- experiments with small actions[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- accesses the (usually small) resources they need to act[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- spends a lot of time paying attention to what is happening, debriefing, learning from the experience, and analyzing what they did -- all to enable them to take a better next step[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

- shares what is learned with the larger network [ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

A self-organized project has an end - when it ends, all the participants can decide if they want to work with others on their next project or not.

Self-organizing becomes transformative when there are thousands of such projects in a network, and each individual is involved in a number of projects, so that innovations and new ways of looking at problems spread rapidly throughout the network, enabling each new project to be more effective. The spread of the use of zoom.us videoconferencing platform by networks over the last two years is an example of how innovations can spread from project to project virally.

Self-organizing is based on the assumption that we don’t know how to solve most of the problems we are trying to solve. Self-organized projects probe the problem, helping us learn more about it and how to best shift the system that is generating the problem.

Another transformative aspect of self-organizing occurs when participants in self-organized projects come together in communities of practice to share what they have learned from their project, support each other with challenges, and discuss how they can apply what they have learned to future projects. When this is shared with the larger network everyone can benefit.

Here is an excellent video of Tamara Shapiro of Movement Netlab on a Leadership Learning Community (LLC) webinar on Self-organizing in Occupy Sandy. Highly recommended!

Friday, Network Weaver will be posting the Self-organizing Toolkit, which you will be able to download for free in the resources section.

In the coming weeks we will outline the simple steps you can take to jumpstart self-organizing in your network.

How have you experimented with self-organizing in your networks? Please share in the comments section below.

June Holley

Foodshed team learns how to establish consent instead of consensus

In Propositions for Organizing with Complexity: Learnings from the Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP), Nikki D’Adamo-Damery described nine propositions that emerged from the work of the AFP. Proposition #2 was: “Establish Consent instead of Consensus.” The following story describes one of the experiences we had together, when Tracy was facilitating the management team, that led to this proposition.

This story begins when the AFP management team was making decisions about how they were going to award mini-grants to on-the-ground projects that addressed community food security. The team included the principal investigators, graduate students, extension agents, and representatives from community-based organizations, and so reflected some of the diversity of the system within which they were working. The team was using a collaborative decision-making framework, and the basis for decisions was the principle of consent.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

The principle of consent

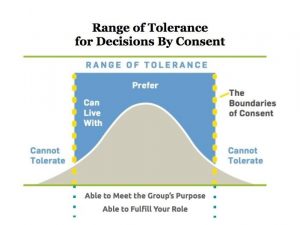

People often think there are only two choices for how we make governance decisions: by majority or consensus. Most people fail to realize that decision-makers have a third option – decision-making by consent – that can be preferable to either of these for governance decisions. The Consent Principle means that a decision has been made when no member of the group has a significant objection to it, or when no one can identify a risk the group cannot afford to take. In other words, the proposal is not out of their Range of Tolerance (see below). Those risks are things that would undermine the purpose, or that would create conditions that would make it very difficult for a member to perform his or her role.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

The test for the management team

The urgency to get the funds out into the field put pressure on the team to make a decision. On the one hand, there was clear value in having these different perspectives at the table as they discussed funding priorities and how to make the application process more accessible. On the other hand, there were conflicting opinions when it came to designing the application. Was it ethical for representatives from community agencies who might apply for the grant funds, to design the actual application? A professor said “no” and a community agency rep said “yes.” There were concerns that the difference of opinion might limit progress.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Consent is grounded in dialogue, not debate

It was through this experience that they learned that, by using consent as the basis for decisions, the team did not have to agree. Instead of debating, they inquired into what was out of the range of tolerance for each of them. They listened to each other’s objections as feedback about potential risks so they could adjust the solution to mitigate those deemed unacceptable.

Here’s what they discovered:

- The professor was actually concerned that there might be a perception about a conflict of interest if the community partners applying for awards were involved in the design of the application questions. That perception was the risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the project’s credibility and trust in the community.

- The non-profit director was concerned about the integrity of inviting community reps into the decision-making process, and then withholding that power when issues got sticky. That power dynamic was a risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the trust within the core team.

Once they discerned the reasons for concern – and chose to respect what was important to each of them – they found a way forward. The decision was to include the community partners in decisions about the application design, as full decision-makers, AND to be fully transparent in all public communications about their participation. As a side note, they were simultaneously clear that, if one of those community-based organizations applied for a grant, they would recuse themselves in the selection of grant recipients.

The grant application design and process went mostly smoothly with no conflict of interest issues. The second round of distribution of mini-grants moved even more quickly, building on the trust that had been built the first time around.

This blog post originally ran on the Virginia Cooperative Extension: Community, Local, and Regional Food Systems blog. and at CircleForward.us

*The Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP) originated in 2011 as a grant funded through the USDA’s Agriculture, Food and Research Initiative (AFRI) grants program (Award Number: 2011-68004-30079). Virginia Tech served as the lead academic institution in partnership with North Carolina State University and West Virginia University for a five-year endeavor to address community food security in western North Carolina, southwest Virginia, and West Virginia.

By Tracy Kunkler, MS – Social Work, professional facilitator, planning consultant, and principal at http://www.circleforward.us/[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Please post any thoughts, comments or stories in the comments section below.

System Shifting Networks

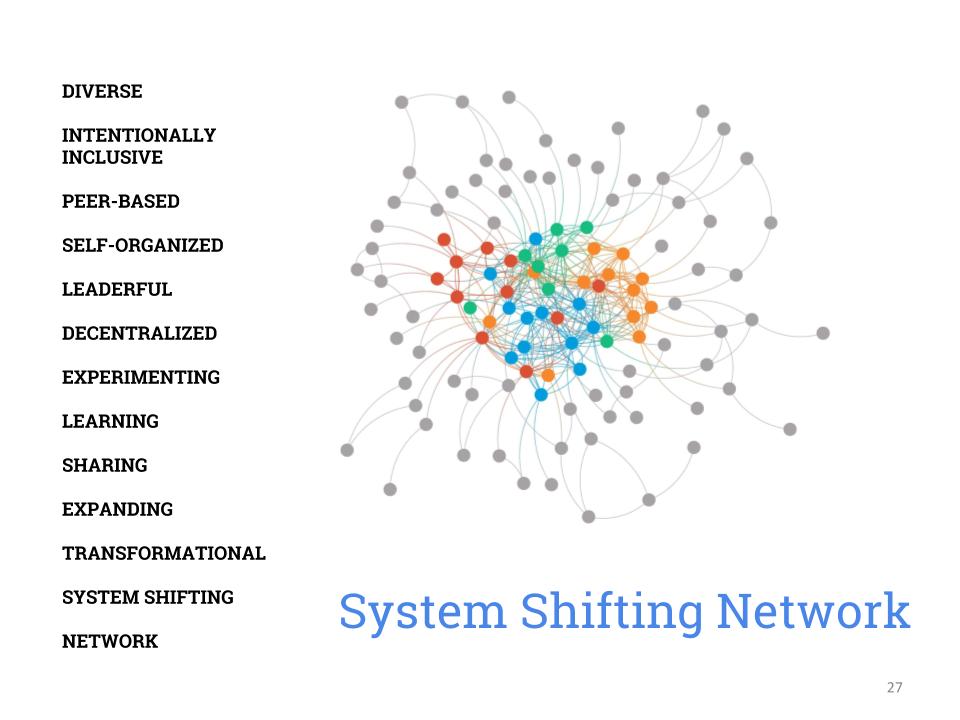

Not all networks are the same! If you are interested in transforming systems so that they are good for everyone, then you are probably helping people co-create a System Shifting Network.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]If you are not familiar with network maps, here is a short guide: [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The circles represent individuals.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The colors represent diversity - you can make maps that show geography, type of organization the individual is part of, race/ethnicity, interests, etc.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The lines represent relationships. You can draw maps where the lines represent different relationships: that the individuals know each other, have worked with each other, or want to work with each other.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The network has a substantial core or center of diverse individuals who know each other or are only a few steps away from others.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The grey dots represent people in the periphery, that is, only one or two people know that individual. People in the periphery are often resource people that can be drawn on as needed, or people from other networks. The periphery should have 3-5 times the number of people in the core.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Here’s what makes a System Shifting Network more powerful in creating change than most types of networks. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Groups of people in System Shifting Networks (SSN's) are continually forming new collaborations to try to learn more about the system they are disrupting and the system they are shifting to. Often SSNs have dozens or even hundreds of these collaborative projects underway at any one time, and many people are in more than one project. Because of this overlap, innovations generated in one collaboration often quickly spread to many other collaborations. Think, for example, about the way the use of zoom.us videoconferencing has spread among people in networks.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- People in System Shifting Networks are continually bringing new people, especially those often under-represented, into their collaborations. These individuals often bring in new perspectives and make people challenge their assumptions, often resulting in much more effective projects.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- In these collaborative projects, people have to scramble to develop new skills and learn new ways of working together. People in these collaboratives work as peers, even though they may identify a coordinator. Everyone in the project learns how to organize and implement a project, and thus there are plenty of new network leaders capable to initiate new projects. So leadership is continually expanding. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Projects are seen as experiments - a way to get more insight into the system they are shifting. They learn what works and do more of it.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- People in projects take time to share what they are learning with others in the network and in other networks so that everyone benefits from every project, whether it was a “failure” or a success.

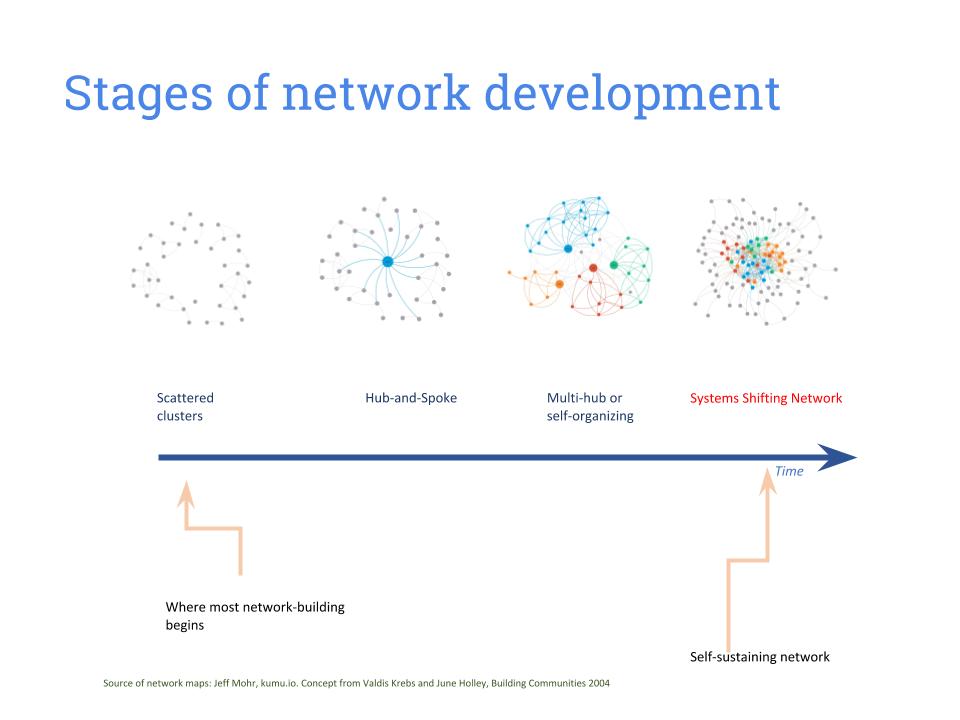

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]But how do we develop System Shifting Networks? Most networks go through 4 stages: [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

STAGE 1: Many networks start as scattered clusters among individuals. Often the relationships in these clusters are informal - people talk to each other in the grocery store and at their child’s soccer game .[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

STAGE 2: Then some individual, organization or group decides to start the formation of an intentional network focused on a particular issue, problem, sector or geography. They become a network hub. They reach out to others they know are interested in the issue and find out about their needs and interests. Often networks stay in this stage, and the hub broadcasts useful information to the interested individuals and has conferences and webinars so network participants can gain new information. However, if a network stays at this stage it loses many of the advantages of networks and will not be capable of changing a system.

STAGE 3: The next stage moves the network to a self-organizing phase. With a lot of support (which we will go into in detail about in future blog posts), individuals or groups in the network start noticing some action that might make a difference and form a collaborative project. Sometimes a network does a system analysis and identifies leverage points and forms working groups to generate experiments in that area. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

STAGE 4: The final stage - a System Shifting Network - emerges when a substantial support structure - communications, learning, restructured money and resources and just-in-time tracking shared with participants - is developed. Projects get larger and have more impact.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]What stage is your network? Please share in the comments section below.

Free Worksheets

We are now offering two network worksheets at no cost.

The first is the Network Weaver Checklist, revised from the NW Handbook version and in an easy to print pdf format. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]This checklist is great to give to people in your network at a face-to-face gathering. Have them spend 5 or so minutes to take the survey. Then have a chart paper (or 2-3 if the group is large). Using a marker, make a line down the center of the the paper and then one horizontally across from side to side. Mark the upper left quadrant with Connector, the upper right quadrant with Facilitator, the lower left quadrant with Project Coordinator, and the final quadrant with Guardian. Then have people put a red dot in the quadrant where they got the most 4s and 5s, and a green dot in the quadrant they would like to learn more about or do more.

Have them pair up with another person and talk about what they learned about themselves as a network weaver and what they would like to learn.

Then have the whole group notice the quadrant(s) where it is strong, and the quadrant(s) where there aren’t many people currently working. Notice which quadrant has lots of green dots - the network may want to do some explicit organizing of training in this are.

To download the Network Weaver Checklist: CLICK HERE

The other free worksheet, Questions for Deep Reflection, is a set of 20 questions that you can use for reflection in your network project follow-up. This list of questions is designed to help you observe what worked and where you might improve.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]To download Question for Deep Reflection: CLICK HERE.

We will be adding new free items each week and will let you know when they are available through our e-newsletter. To sign up for the e-newsletter click on the button below.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

A NETWORK OF NETWORKS

Editor’s note: I’ve become more and more convinced that networks are much more effective when they are also part of networks with other networks, where they can share information, learn, support each other with challenges and organize larger collaborative actions especially policy change. We will have a series of blog posts in the coming weeks about the different types of networks of networks and steps in developing them.

Food system networks have been in the forefront of this development. Here Ken Morse describes the Maine Network of Community Food Councils.[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Higher Level Network of Networks

I co-coordinate the Maine Network of Community Food Councils (MNCFC), made up of a growing number of community councils (currently 12, mostly multi-town) that act as local networks, with the Maine Network knitting these together in a Network of Networks.

For the last year, we have been organizing conversations with many other Maine groups with the idea of weaving together the over 100 groups, networks and non-profits working towards rebuilding Maine’s food supply. So a higher level Network of Networks, or you could almost say a Network of Networks of Networks.

We try to study biological models of organizations, seeing “networks” as a biological approach to social organization, much the way sustainable food systems are a biological alternative to industrial agriculture.

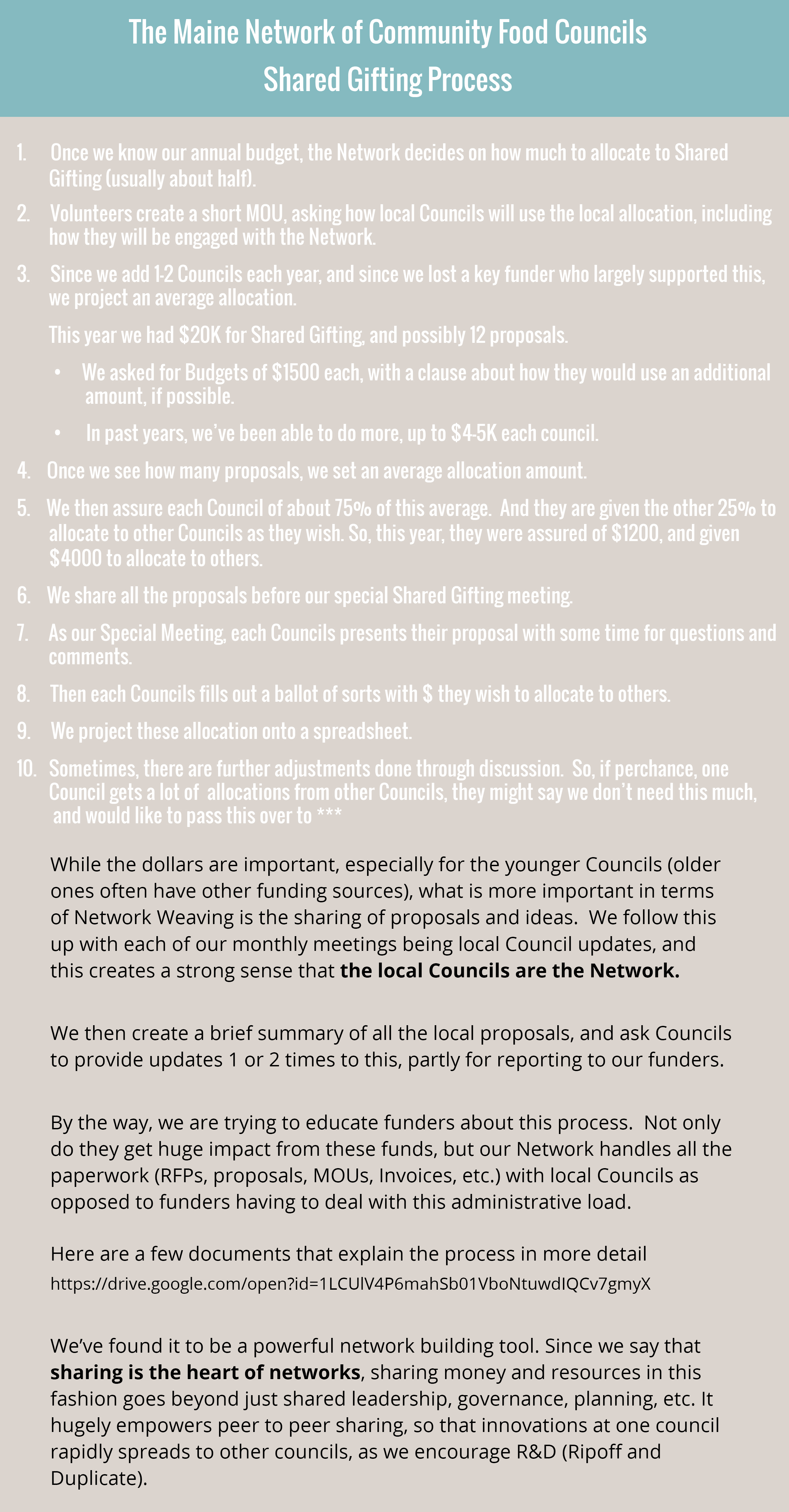

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]The Shared Gifting Process

One tool we have used within MNCFC is our Shared Gifting process. MNCFC is largely grant supported and we devote about half our budget to allocations to local councils, using a Shared Gifting process that we adapted from RSF Finance in California. All Councils submit proposals for this funding, all proposals go out to all Councils, then we have a special Shared Gifting meeting, where each council presents their proposals. Each Council is assured of funding for part of their work, and then have an allocation that they can share with other Councils. [ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]Here are a few documents that explain the process in more detail.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]Enriching Peer to Peer Sharing

This process mightily enriches the peer to peer sharing at the heart of MNCFC. Each Council learns about the work of the others, and then our meetings throughout the year are heavily focused on Community updates. Councils really begin to feel like they are the network, and innovation is greatly accelerated through replication of local initiatives across the Network.

We are interested in other network building tools like this. And in our “networks of networks” work, we are especially interested in questions of structure and communication ecosystems. And stories about how we can help folks who are somewhat stuck in organization or institutional frameworks to make the leap into network mindsets.

So, in any regard, we are delighted to be connecting with you and other national partners to dig deeper into this cutting edge work. [ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Ken Morse

Community Food Strategies

Co-Coordinator, Maine Network of Community Food Councils

Leadership Team, Maine Farm to Institution[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Another wonderful resource Ken shared with me is a video call with four State Food Networks of Networks https://youtu.be/6wgIvqzHs8E. If would like to learn more about statewide food networks, also check out this article by University of Minnesota Extension on Cultivating Collective Action: The Ecology of a Statewide Food Network (2015)