EXPLORING THE COLLABORATION CYCLE

Below is an excerpt from the full article which can be downloaded here or at the bottom of this post. This article a part of the Tamarack Institutes Collaborative Governance and Leadership series.

The Collaborative Context

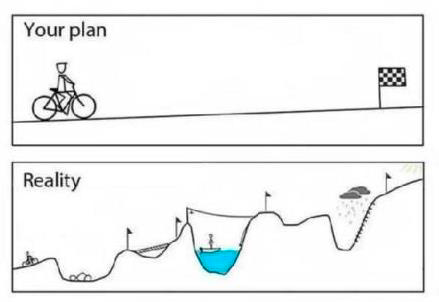

Many enter into collaboration thinking that the shared work is a linear and flat process from start to end. One of the favourite images describing collaboration that is often included in Tamarack power points is this image of plan versus reality. It captures the reality of collaboration including the twists and turns that collaborative efforts face as they move from start to completion. It can include obstructions like boulders and choppy waters and other challenges which are found obstructing the path along the way. This image always receives a small chuckle because individuals in the room have experienced these challenges.

However, the reality image still conveys a relatively linear, if upward, and challenging experience. This image is relevant for collaborative efforts seeking to achieve a result that is more defined such as the exchange of ideas, or development of a new program or service.

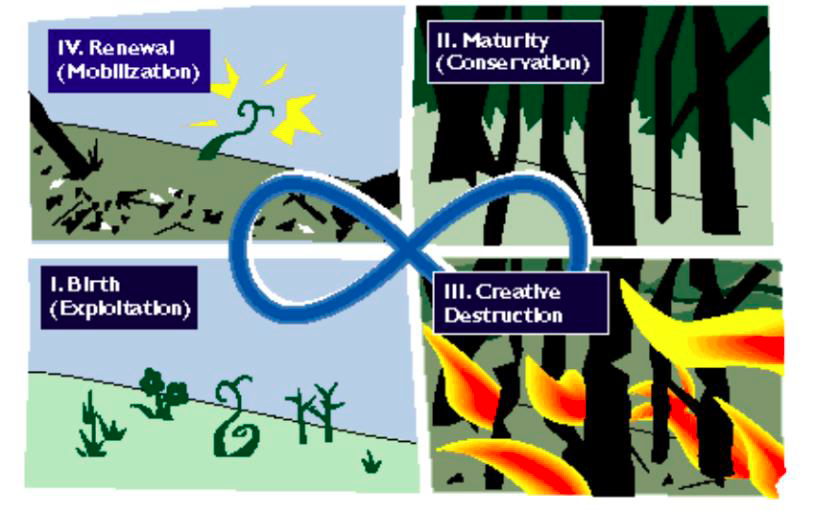

For more significant community change efforts, a different approach was introduced to Tamarack by Brenda Zimmerman of The Plexus Institute. Zimmerman described community change as a more cyclical process mirroring phases of development found in ecology.

The ecocycle concept is used in biology and depicted as an infinity loop. In this case, the S curve of the business school life cycle model is complemented by a reverse S curve. It is the reverse S curve, shown below with the dotted line, that represents the death and conception of living systems. In our depiction of the model, we call these stages creative destruction and renewal. The importance of the infinity loop is that it shows there is no beginning or end. The stages are all connected to each other. Hence renewal and destruction are part of an ongoing process.

Being an infinity cycle, there is no obvious start or end to the cycle. Let us begin our examination of the stages at the beginning of the traditional S curve. We will begin each phase by using the biological example of a forest and then look at the analogous phase in human organizations.(i)

The four phases of the ecocycle, as described by Zimmerman and the Plexus Institute follow the traditional (and linear) growth curve from birth to maturity. However, it also considers a renewal loop. The renewal loop includes a creative destruction phase and a renewal phase.

The image from the Plexus Institute website displays and describes the ecological cycle of a forest which starts with a variety of different plant growth (birth) which leads to increasing density as the forest grows to maturity. At maturity, the forest becomes increasingly vulnerable because of the density of growth. It can experience rot through invasive moths or pests or be ruined because of a forest fire. The creative destruction phase creates the space for renewal and regrowth. It is often the results of decay that enable the regrowth or renewal to seed.

Using the Ecocycle to Inform Our Practice

The ecocycle has been adapted by many organizations over the last several years to describe a better way of understanding community change and collaboration cycles. Tamarack has used the ecocycle to inform our practice of supporting communities tackling complex issues like ending poverty, building youth futures, deepening community, and navigating climate transitions. Tamarack, influenced in our early years by Brenda Zimmerman, recognizes that communities are dynamic and responsive. Even as collaborative tables begin to intervene in community change efforts, the community begins to respond, grow, and change. The ecocycle approach can be useful to collaborative tables to help understand and navigate dynamic change recognizing that change is not linear but rather exists in phases and cycles.

From Ecocycle to Collaboration Cycle

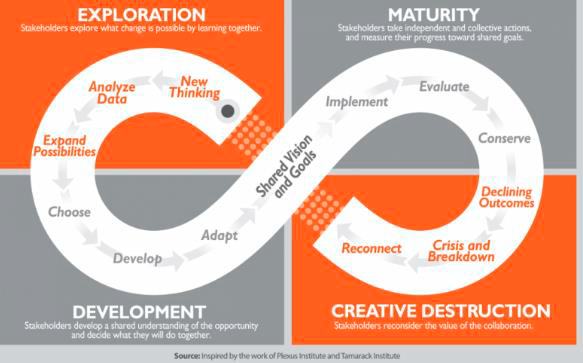

There have been many articles written about the Ecocycle and adaptations to this approach. One useful adaptation of the ecocycle was developed by Chris Thompson, Collaboration – A Handbook from the Fund for our Economic Future. (ii) In this handbook, Thompson adapts the ecocycle to a collaboration cycle approach. Thompson builds of the Plexus Institute ecocycle framework and Tamarack’s approach to adapting the ecocycle to community change efforts. Thompson uses the phases language of development, maturity, creative destruction, and exploration.

Thompson describes three elements which are vital to impactful collaboration: capacity, process, and leadership. The collaboration cycle is useful to focus on the process of collaboration.

This cycle serves as a roadmap for the diverse players who are along for the collaboration journey. It is invaluable to new participants joining an existing collaboration, as it can be used to help them understand where the partners are on the journey. Advocates of collaborations, particularly those performing the key collaboration functions, also should take the time to help each partner assess where they are on the cycle. Not every partner travels through the cycle at the same pace. (Thompson. Page 29) Thompson provides useful steps in each of the phases such as developing new thinking, analyzing data, and expanding possibilities in the exploration phase

In the development phase, the steps include choosing strategies, developing approaches, and adapting as the collaboration moves forward. The maturity phase includes implementation, evaluation and in some cases conserving to build on successful results. The creative destruction phase is initiated by declining outcomes, crisis, or breakdown and reconnecting.

Access the full article HERE

Liz Weaver is the Co-CEO of Tamarack Institute and leading the Tamarack Learning Centre. The Tamarack Learning Centre advances community change efforts by focusing on five strategic areas including collective impact, collaborative leadership, community engagement, community innovation and evaluating community impact. Liz is well-known for her thought leadership on collective impact and is the author of several popular and academic papers on the topic. She is a co-catalyst partner with the Collective Impact Forum.

Liz is passionate about the power and potential of communities getting to impact on complex issues. Prior to her current role at Tamarack, Liz led the Vibrant Communities Canada team assisting place-based collaborative tables to move their work from idea to impact.

featured image found here

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

The Art of Collaborative Facilitation

“An effective facilitator is often what makes the difference between success and failure,” write Paul W. Mattessich and Kirsten M. Johnson, authors of Collaboration: What Makes It Work. “Facilitation isn’t magic, but it is multifaceted, challenging, and essential.”

If design is the framework or skeleton of a meeting, facilitation is what brings it to life. The work of a facilitator is to sense and respond to the needs of the group, while simultaneously guiding the network toward meaningful shared outcomes.

The crux of good facilitation, according to Adam Kahane, author of Facilitating Breakthrough, is not to get people to work together, but to remove the obstacles to connection and collaboration—obstacles like disconnection, debilitating conflict, and other forms of “stuckness.”13 After all, the Latin translation of the word facilitate is “to make easier.”

Picture a river: while you can’t push a river to move in a certain direction, you can remove rocks and logs impeding its path to allow the water to flow by itself. Good facilitators do not force things forward; they hold space for all points of view to be acknowledged while helping the conversation to flow.

Facilitating in collaborative contexts has a lot in common with good facilitation in any setting. As with any facilitation, it’s important to set the context for the gathering, ask good questions, and invite divergent perspectives. Facilitators also need to be able to acknowledge and disrupt harmful power dynamics to ensure that people have maximum agency to contribute.

In addition to these fundamentals, facilitating in a collaborative environment calls for operating with a network mindset. This means trusting the group rather than trying to control it, embracing emergence, inspiring self-organization, and naming dynamic tensions as they arise. It means embodying the norms they wish to see in the group. In many ways, the group will mirror the energy of the facilitator.

Facilitators are also tasked with demonstrating a comfort with ambiguity, with not knowing. The job of a facilitator is not to have all the answers. Instead, it is to ask good questions and help participants navigate the inherent complexities of life.

Drawing from experiences facilitating countless meetings with colleagues over the past ten years, we see the following as fundamental practices of good facilitation:

- Show up with your whole self

- Frame the context

- Hold space

- Invite divergence

- Stay emergent with intention

- Lead with humility

Show Up with Your Whole Self

As a facilitator, you have a specific job to do. But you’re also a complex, multifaceted human being. Bring the many sides of yourself to each convening as a way to model wholeness for the group. You do not need to be perfect. You will make mistakes, just like everyone else. Use humor and laughter to break moments of ten- sion and acknowledge shared imperfections and humanity.

Reveal emotion. Be open. Show the soul behind the role. It can make all the difference in the world. As you invite people to share why they have decided to participate, don’t be afraid to reveal why the work matters to you, as well.

Frame the Context

Imagine the very beginning of a convening. Everyone is gathered together, some for the first time. There you stand, ready to begin the session. What are the first words you will say? Think carefully, as they are vitally important. While it may be tempting to jump into the work of the day and blow by the opening, don’t miss this powerful moment. The opening to a convening is not a mere formality. “When we optimally prepare people for the form, function, and purpose of our gathering, they will be present in a way that greatly improves the chances of our purpose being actualized,” write Craig Neal and Patricia Neal in The Art of Convening.

Though the opening is a particularly significant moment, it’s also necessary to frame the context throughout the convening, including whenever you launch groups into a new activity or dis- cussion, as well as at the end of each day. Think of framing as the essential practice of clarifying the state of the moment and preparing the group for the work ahead. The best frames integrate what you heard from participants and contextualize the purpose of the convening or a particular session in a way that will increase engagement in the activities that follow.

Hold Space

There will inevitably be moments in convenings when the temperature in the room starts to rise. These are times when the conversation gets tense, people feel on edge, and nobody wants to openly acknowledge it. At this moment, many people will be tempted to retreat into what Robert Solomon and Fernando Flores call “cordial hypocrisy”—nice, polite conversations where real issues are swept under the rug.

The facilitator’s role here is to acknowledge what’s happening, invite people to take a breath, and then hold space so that the real issues can be worked through. Acknowledging what is happening can take the sting out of it, reducing the anxiety that the discomfort brings. Reminding people to stay present in the conversation may help them avoid falling into a stress response of “fight, flight, or freeze.” These are the moments of truth, the times when groups can either fall back into what’s comfortable or sit in the tension long enough to acknowledge unspoken realities and address critical issues.

Invite Divergence

Collaborative facilitators invite divergent perspectives, rather than avoid them. This is what enables participants to think creatively together, even when they disagree. When addressing an important issue, people may make statements so emotionally charged that they risk being isolated or labeled by others. At that moment, facilitators may feel the urge to move past the dissenting input and get back to the task at hand. What happens next can change the course of the group’s collective culture.

As a facilitator, instead of avoiding the disruption, turn to that person with your full attention and ask them to elaborate. Then, check to see if others feel similarly. If nobody does, you still need to validate that person’s perspective. It doesn’t matter if you agree or disagree with their opinion; what matters is making the room a safe place for different perspectives to be shared and honored. I learned this practice from Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff, creators of the Future Search process, and it’s served us more than a few times. By validating that person’s perspective, you make them feel heard, which allows the person to relax and rejoin the flow of the conversation.

Then, consider inviting people to share their own perspectives. This opens the space for people to offer contrasting opinions in a way that is respectful. These moments can dramatically shift the way in which participants interact with one another by creating a sense of psychological safety and appreciation for diverse points of view.

If you become stuck when something is going on in the room and you’re not sure what to do, put your faith in small groups or pairs. Quickly break the participants into groups of two to four, and ask them to discuss what’s happening in the room and what they think needs to happen next. Reflections can then be shared in the full group, which may give you a clue as to how to proceed (this might be a great time for a break as you quickly redesign the agenda!). This is one of Peter Block’s favorite tactics. “In doing this,” he writes, “we ask the community to take responsibility for the success of this gathering and express faith in their goodwill, even if they are frustrated with what is happening. . . . Doing this is an acknowledgment that critical wisdom resides in the community.”

Stay Emergent with Intention

No agenda is likely to survive contact with reality. As a facilitator, you have to be ready to adapt on your feet, sensing into where the energy is and what needs to happen next. At the same time, your facilitation shouldn’t be so loose that conversations are scattered. It’s a delicate balance of being open to emergence while being deliberate about closing conversations to move things forward.

In Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, Sam Kaner points out that groups in conversation typically need to move through a process of generating divergent and creative ideas before converging and arriving at a decision point. As facilitators, we give groups the space to sense their way through these conversations and the autonomy to shift from one conversation to the next. But before moving on to a new topic, we check to see if the first conversation can be closed with clarity—which may simply be a next step. If a conversation cannot be closed, we have the group acknowledge that they are purposefully shifting the focus of the discussion.

Lead with Humility

The role of the facilitator has inherent power. Facilitators usually have the final say over the agenda, they orchestrate the flow of the conversation, and they can influence who speaks and when. The act of facilitating is an act of exercising power. Facilitators use that power thoughtfully to make the gathering as welcoming, equitable, and open to shared leadership as possible.

As a facilitator, first examine your own privilege and implicit biases and acknowledge the power that comes with the role. Then, invite participants to provide candid feedback if they recognize opportunities to make the space more inclusive. If you come from a dominant cultural group, it is especially important to consider other cultural frames in the meeting design phase as well as in real time during a convening. Otherwise, you run the risk of unconsciously reinforcing dominant group norms that can alienate or even cause harm to some members of the group. When facilitators are too passive, they fail to fulfill some of the critical responsibilities of the role. “Far from purging a gathering of power,” passivity creates a power vacuum that others can fill “in a manner inconsistent with your gathering’s purpose,” writes Priya Parker.

Instead, I recommend practicing what Parker calls “generous authority”: lead the meeting confidently but also with humility, owning the power you’ve been entrusted with while using that power in service to others and to the group as a whole. Rather than using power over others to shut people down or control the conversation, emphasize power with, among, and within, to increase shared leadership across the group and guide the meeting toward life-affirming outcomes.

This piece is dedicated to David Sawyer, one of the best facilitators I’ve ever known.

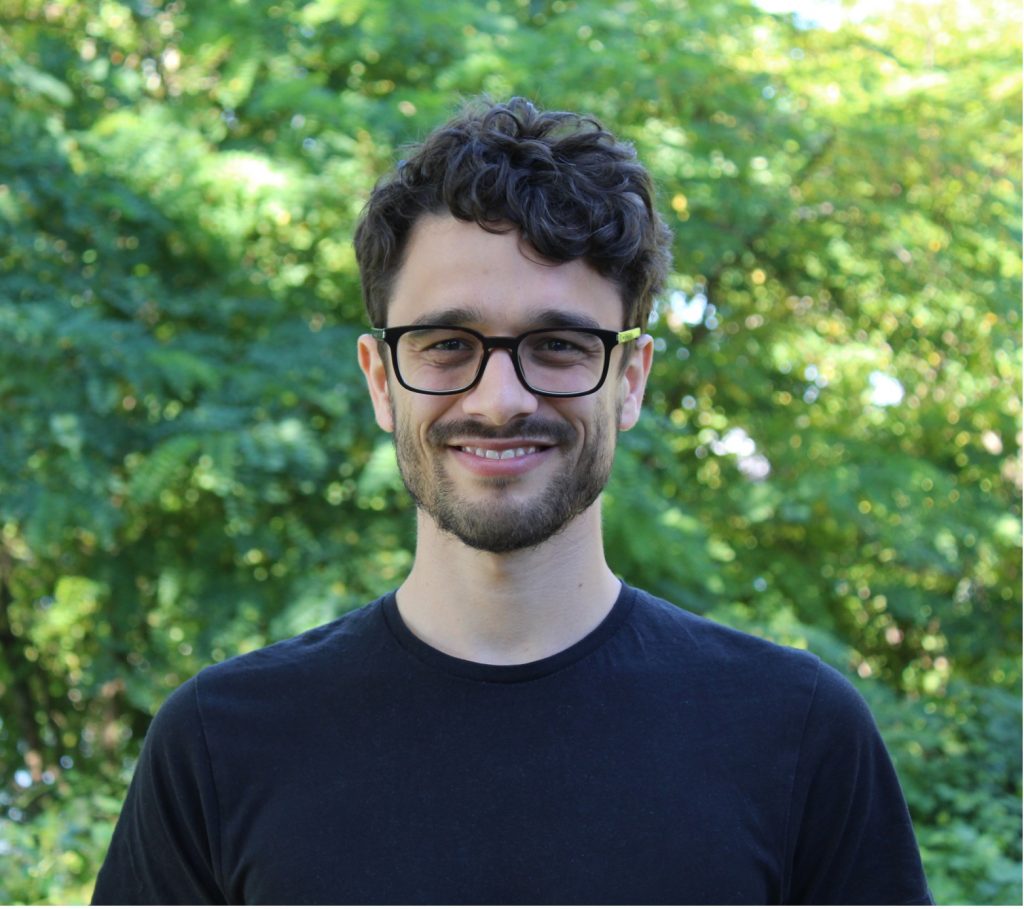

David Ehrlichman is author of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change (impactnetworks.xyz). He is currently working as cofounder and ecosystem lead of Hats Protocol (bit.ly/structurewithoutcapture), working to unlock a new paradigm of human coordination. From 2013-2023 David was cofounder and coordinator of Converge (converge.net), a network of practitioners who build and support impact networks.

David has helped form dozens of impact networks in a variety of fields, and was a founding coordinator for networks in the fields of environmental stewardship, economic mobility, access to science, civic revitalization, and web3. He speaks and writes frequently on networks and the future of coordination, finds serenity in music, and is completely mesmerized by his 1.5-year old daughter. Find his podcasts, writings, and other projects at davidehrlichman.com.

featured photo by kazuend on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

Understanding network strategy

Every organization needs an effective strategy. Strategy can refer to an overarching strategic plan at the organizational level or a strategy towards achieving specific organizational needs and goals. A strategy will set the way forward for an organization in alignment with its overarching vision and mission. It will articulate the priorities and directions the organization should take as well as convey the “what”, “why”, and “how” to accomplish its goals, often within a given period, by clearly defining the pathways towards achieving them.

At Collective Mind, we’ve learned a number of lessons through our work with networks developing strategies and strategic plans.

Context matters

Strategy for networks is different than strategy for more traditional organizational models. Networks are a unique type of organization with a complex operating model. They are different in how they’re organized, who’s involved, and how they get things done.

First, networks are horizontal, flat structures: they are not top-down, hierarchical, or directive. They are loosely controlled, with multiple mechanisms for collaboration and without any mechanisms for command and control.

Second, networks are comprised of members — without members, you don’t have a network — and the complexity of that membership typically matches the complexity of the network’s issue area. As such, the network must meaningfully integrate a wide diversity of people and/or organizations in an equitable fashion. It must be flexible and agile enough to capture the emergence that arises from such diversity and the interconnections across it.

Finally, because of these characteristics, networks operate differently. They seek to harness the collective intelligence within them, dispersing leadership and sharing decision-making. They typically don’t procure deliverables but focus on stimulating activities by their members, who are responsible for creating the outputs of the network. This relationship between members and the network is typically voluntary and about creating shared value, not premised on a contractual relationship. Consequently, the network’s staff (if there is a staff) aims to support its members by helping facilitate the production of outputs, rather than directly implementing and delivering those themselves.

How networks are different influences strategy

Within this unique and complex operating environment of networks, we can consider strategy differently in at least three ways: process, content, and implementation.

Process: we must ensure that the process to develop the strategy or strategic plan empowers members and any other stakeholders and establishes their ownership of it. This requires a participatory, inclusive process with mixed methods for inclusive, meaningful participation. An iterative and adaptive process should build from one step to the next toward the final strategy. The steps of the process should ensure ongoing triangulation and validation of key ideas, needs, priorities, and pathways with stakeholders as they are developed.

Content: we must ensure that the strategy or strategic plan represents a collective effort. It should set collective priorities and determine the collaborative paths to achieve them by facilitating consensus-building throughout the process. The plan’s priorities and goals should be grounded in the needs, interests, and capacities of the membership. The substance of the plan must reflect the goals, expectations, and motivations of the members.

Implementation: we must clarify and define who will implement the strategy. As explained above, in the context of a network, it must be its members that produce the outputs with support from the network staff. We must clarify how this can be done realistically and right-size the strategy to ensure the feasibility of that implementation (for example, recognizing the limitations on members’ capacity, time, etc.). We must ensure that the plan supports the network to align energy, resources, and stakeholders for collective impact.

A clear and effective strategy will define in what direction the network and its membership will move forward. It will reflect and align with the needs and interests of its members, defining initiatives and activities through which members can participate and collaborate. Consequently, it will clearly articulate the unique added value that the network as a collective can create that is greater than the sum of those parts.

Interested to hear more about how we approach strategy development with networks and how we can support you? Contact Kerstin Tebbe at kerstin@collectivemindglobal.org.

Kerstin Tebbe has almost 20 years of experience supporting networks and multi-stakeholder collaboration. Kerstin founded Collective Mind in late 2019 after many years of independent study and research on networks. With Collective Mind, she has supported networks from local to global on a wide range of challenges. Kerstin has lived and worked in New York, Buenos Aires, Paris, Nairobi, Geneva, and Washington DC. When she’s not thinking about networks, she’s dancing.

originally published at Collective Mind

Illustration by Patrick Hruby, found HERE

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

On Collective Liberation and Natural Networks: an Interview with LLC’s Nikki Dinh and Ericka Stallings

I was able to meet with the Co-Executive Directors of the Learning Leadership Community, an organization I’ve long admired for their commitment to a community-focused transformative leadership practice. This past year, LLC was able to return to a co-Executive Director model which has freed up both Nikki Dinh and Ericka Stallings to focus on shifting LLC towards a more liberatory transformative leadership model. Part of this shift involves supporting the ongoing work of Network Weaver as it provides tools and resources to scale up access to weaver spaces and serve as a platform that amplifies the impact of BIPOC weavers and leadership practitioners on their communities. More deep-rooted shifts involve the difficult work of making even more room for thinking about and practicing liberatory frameworks that make equity work within this system sustainable for people who come from othering backgrounds.

“We look at leadership as a tool for transformation. To say that we are “equitable” within this current system, which is in and of itself inequitable is not necessarily our goal. Racial Equity being a path towards liberation, that's the change that we're trying to seek.”

– Ericka Stallings

In this interview, we talk a little bit about both Nikki and Ericka’s vision for LLC, liberatory processes, how community is the first network we come into, and why the work LLC is doing matters right now. Nikki and Ericka’s responses have been edited for clarity, but all effort has been made to maintain the integrity and spirit of their words.

* * *

Can you talk to us a bit about liberatory processes?

Nikki: “Liberatory” is a why, but it's also a how for me, because it's not a destination. It’s not like race equity, where you can measure your way to a certain point in the data and then it switches over to being more equitable for certain communities. Liberation, collective liberation, co-liberation, however you want to see it, is going to be a forever journey. We’ve seen what it does to our community members when non-profits focus only on getting the data or policy right—there’s a disconnect. And so how we do it really matters to people. Ericka and I always talk about what it takes to make a movement or network whole. How do we get to just work in just ways? It's not the technical titles like executive director and weaver, though we need those too, but what we know from our experiences is that we need everybody--we need somebody like Ericka’s mom who will nurture you, and we need an aunt who is always keeping an eye out for all the resources and trying to connect people to them. The “how” stems from a deep love for people. We’re trying to bring some of that back, some of that love and care for each other while we're doing this really difficult work.

What's one thing that that Network Weaver, or even LLC is doing differently, to transform the field of leadership?

Ericka: We are shifting towards a different lens that asks: what does a collective liberation look like? What does it mean when we free ourselves and each other? That’s one change. We are also getting clear about what these questions around equity, liberation and transformation mean in different contexts. LLC is mostly domestic, whereas Network Weaver is international and therefore has a broader reach. Networks are not just interesting tools, but they actually result in change. How can we explore what a change ecosystem looks like and the role leadership plays in that? How can really thinking about the needs of varying stakeholders, and not just being focused on terms and buzzwords that are exciting, help us capture all the work that goes into the change process? How do we support the leadership of all of those other folks who are in that ecosystem? Holding space for those questions and others is one way I think we’re committed to doing things differently.

What is your vision for Network Weaver?

Nikki: Network Weaver is a tool and resource. Ericka and I have this analogy about pollination. In areas where bees and butterflies and all the natural super pollinators are dying off, there are efforts to self-pollinate or find other ways to pollinate. And that's why Network Weaver is so valuable to me. It's like an artificial butterfly. It’s trying to help solve a crucial short-term problem until we can get that butterfly population back up. It’s a useful tool to scale when we need to scale, but how can we also pay attention to what makes bees and butterflies thrive in the natural habitats because the goal always is to have natural networks. Growing up in a refugee community, we had a large cultural network and within that so many alternate systems to meet the needs of the community. You need to borrow money? You need prescription pills? There were people doing that for each other! I envision us also zooming out to see and appreciate a natural network of weavers that continue to connect and build alongside the Network Weaver space.

What's your vision for LLC?

Ericka: Oh, we have lots of ideas and hopes and dreams for LLC! Something that I hope doesn't change is that LLC is very relational. LLC is very people-focused, we care about people. It’s also a space that welcomes joy. And that's something we want to grow into. A vision that I have for LLC is that it is a space where people who want to lead in liberatory ways, and folks who want to support leadership that is transformational and liberatory, can collaborate. We are a space of experimentation, innovation, and community. I hope as a consequence of our work, that there are stronger movements for justice.

One of the things that I appreciate about LLC is that we are eco-centric rather than egocentric, which is something that our founder, my predecessor, used to say frequently, and I really value not having to make sure everyone knows that “it's us.” It’s more important that the work happened, rather than the credit be attributed to us. That focus on the communal, the collective, the ecosystem is something that remains part of the vision that I have for LLC. Our work has not just been about products and deliverables, but liberatory processes, and that has made the work fulfilling and joyful.

What’s a commitment you made to yourself during the pandemic that you intend to keep?

Nikki: I have made a commitment to root for me. It’s still a journey. I am surrounded by people like my sisters, my partner and my children, my collaborator Ericka, who think I'm so great. And I want to take on some of that energy and be like, I'm going to do it for me. And that's what has really emboldened me to be like, alright, look, we're doing liberatory work, we're gonna go there, because, you know, I was a lawyer—I know you can’t undo that kind of systems thinking overnight. I’ve had to work on this and believe in valuing this. And I've also known, because of my upbringing, that we can do better. So rooting for me is rooting for all folx entrenched in systems, for us to be a bit freer.

Ericka: One, I mean I have one commitment that I've made that is unexpected. And it's a group of women that I have coffee with, like virtual check ins with weekly.. We've been doing it since the beginning of the pandemic. The funny thing is we were not intimate friends before. We started this gathering to have regular conversations with agendas and learning goals and things like that, and they evolved or de-volved, depending on how you think about it, into very, very rich, deep emotional connections. I'm very proud and happy that I've continued to commit to these weekly check ins and also to those relationships.

Is there anything that you're like most excited for this year?

Nikki: We're doing some longer-term strategy work. In the next three to five years we will go bold with liberatory programming. Our lens for Network Weaver, for example, will be situated under the liberatory program side of the house. Everything we do will have to bring a kind of outside-the-system thinking which includes bringing in the perspectives and interests of people who are typically excluded from our systems. That said, I'm really excited to work with more people who are from other backgrounds, like refugees and trans folks, and queer folks, and people with disabilities. I have learned so much from people outside of our systems that I'm really excited for others to get that wisdom too.

Why LLC? Why Donate Now?

Ericka: One of my favorite quotes is: “if you give me a fish, you have fed me for a day. If you teach me to fish, you have fed me until the river is contaminated or the shoreline seized for development. But if you teach me to organize, then whatever the challenge, I can join together with my peers and we will fashion our own solution.”

With that in my mind, my hopes for the ongoing work of LLC and Network Weaver are in that vein; of prioritizing the people who are addressing issues in their communities and how folks in this space are supporting them. I'm hoping that the blog series we hope to launch soon will address how people are affirmatively and explicitly stepping back so that the people directly impacted come to the forefront. And I'm hoping these stories about the material, communal, and spiritual transformation that's happening help us see the real impact people are having on the communities they care about.

donate in the box above or click here

Ericka Stallings is the Co-Executive Director of the Leadership Learning Community (LLC) a learning network of people who run, fund and study leadership development. LLC challenges traditional thinking about leadership and supports the development of models that are more inclusive, networked and collective. Prior to LLC, Ericka was the Deputy Director for Capacity Building and Strategic Initiatives at the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD), supporting organizing and advocacy and leading ANHD’s community organizing capacity building work. Ericka also directed ANHD’s Center for Community Leadership (CCL) which provides comprehensive support for neighborhood-based organizing in New York City. At ANHD she formerly directed the Initiative for Neighborhood and Citywide Organizing (INCO), a program designed to strengthen community organizing in the local neighborhoods. Before working at ANHD she served as the Housing Advocacy Coordinator at the New York Immigration Coalition (NYIC), managing its Immigrant Housing Collaborative. In addition, Ericka co-coordinated the NYIC’s Immigrant Advocacy Fellowship Program, an initiative for emerging leaders in immigrant communities. She received her undergraduate degree from Smith College, studied International and Intercultural Communications at the University of Denver and Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University.

Nikki Dinh is the daughter of boat people refugees who instilled in her the importance of being in community. Though she grew up in a California county that was founded by the KKK, her family’s home was in an immigrant enclave. Her neighborhood taught her about resistance, resilience, joy and love.

Her lived experiences led her to a career in social justice and advocacy. As a legal aid attorney, she learned from and represented families in cases involving immigration, domestic violence, human trafficking, and elder abuse. Later, she joined the philanthropic sector where she learned from and invested in local leaders, networks and organizations throughout California. At Leadership Learning Community, she is excited that her work will continue to be guided by the belief that the people in communities we seek to serve are best positioned to identify and create solutions for their community.

About the Author

Sadia Hassan is a writer, organizational consultant and network weaver who enjoys using a human-centered approach to think through inclusive, equitable, and participatory processes for capacity building. She is especially adept at facilitating conversations around race, power, and sexual violence using storytelling practice as a means of community engagement and strategy building. She has received a Masters in Fine Arts, Poetry at the University of Mississippi and a Bachelor of Arts in African/African-American Studies from Dartmouth College. You can read more of her work at Longreads, American Academy of Poets, and The Boston Review. https://sadiahassan.com

feature photo by Lee 琴 on Unsplash

Inside philanthropy and networks

Collective Mind hosts regular Community Conversations with our global learning community. These sessions create space for network professionals to connect, share experiences, and cultivate solutions to common problems experienced by networks.

In July 2021, Collective Mind hosted a unique Community Conversation panel discussion about philanthropy and networks. The session featured experts who work across the philanthropic space and have deep experience with networks ranging from global and national to hyper-local levels and across the gambit of social causes. The panel included Heather Hamilton, Executive Director of the Elevate Children Funders Group; Hilesh Patel, Leadership Investment Program Officer of the Field Foundation; and Katie Davies, Manager of Strategic Networks Initiatives with Ignite Philanthropy.

Together, the panelists explored the most urgent topics on their minds as funders and funder organizers for social impact, and talked about the trends they’re observing within philanthropy as it evolves toward more progressive causes and systems-change work. The panel helped elucidate some of the mysteries behind philanthropic decision-making and strategy, and sparked conversation among participants about how networks can reimagine their approach to and relationships with donors.

Highlights from the conversation

Understanding the decision-making structures of philanthropies helps network practitioners see their work through a donor’s lens and ask themselves the questions donors need to have answered. According to the panel, grant seekers commonly overlook the disconnect between program officers (POs) and where high-level funding decisions are made. POs are engaged on the ground, hearing directly from leaders and impacted communities, and have a current view of how the field is evolving to help advise on strategy. But ultimately, the Board of Directors controls the purse strings and sets the strategic agenda, with POsimplementing their decisions. Boards often prioritize questions of financial risk when making strategy and investment decisions, as well as the potential for fiscal return or reward. Among the range of types of foundations, POs will also have different levels of autonomy and instruction and at times won’t have a lot of flexibility in what they can fund. For networks, this can be particularly challenging as the work and value of networks can be amorphous and long-term, presenting more perceived risk from a business point of view.

Furthermore, networks may not necessarily fall into the framework of how traditional Boards think of how change happens. By design, networks work collectively toward a goal or contribute to a solution, rather than being able to specifically claim impact as their own, which makes their value proposition less straightforward and tangible than programmatic outputs and numbers. To demonstrate impact for donors and stakeholders, groups will sometimes overclaim and attribute wins to their own efforts, which misrepresents the work and can undermine the notion of a shared purpose. This can muddle the message of how collective impact happens and its value. It is therefore both on networks to be thoughtful, effective storytellers and have strong mission clarity, and on donors to educate and challenge themselves on their conceptions of the role and value of networks to affect systems change and foster an enabling environment where change happens.

Effective philanthropy requires more and better Board education. At its roots, philanthropy assumes a binary between those doing work on the ground and seeking funds and support, and those with resources who make big decisions on behalf of social change work but have limited practical knowledge or experience of it. This dynamic is challenging to navigate and also problematic. More and more, POs are working to educate Boards, which are often composed of wealthy individuals, about social change and to create change within foundations on the inside. There is emerging interest in the philanthropic space to learn from and with communities of change and to become more responsive and accountable across leadership and decision-making. Networks can help POs in their efforts to push and educate leaders within foundations to understand more about movements, collectives, and networks, and how donors can be more effective partners for change.

One way this can be done is through measurement methods that are more true to life and the work of social change. Donors often miss that funding networks means that progress won’t always be linear or explicit. Not only can fixed metrics and reporting requirements put a burden on grantees and have undue influence on the work, but limiting impact work to spreadsheets and formulaic processes can drive artificial outcomes and stifle the chance to glean real learning and value. For some foundations, there’s a new effort to pivot traditional reporting requirements and formats to be more flexible, conversational, and focused on multi-directional learning. These processes reframe accountability to center what grantees and donors can learn from each other about how the field is evolving, what role they all play, and what progress is being made. Doing the work to understand why networks and coalitions are important leads to understanding the nature of networks and systems change.

Donors are also starting to embrace how the image and dynamics of leadership are shifting through the work of networks and movements. Whereas traditional leadership is marked by an individual with certain, often normative characteristics and the vision and actions they represent, networks and movements center the leadership of groups and shared efforts. In networks, there is often no one leader: leaders are pulled from different sections to be part of broader work, and the model and mission doesn’t prioritize individuals as leaders. These challenges to traditional notions of what leadership looks like both mirrors and goes beyond how the face of leadership is already changing generationally. Understanding networks for how they upend traditional leadership is another way to educate philanthropic Boards about collective action and collaborative leadership.

Miss the session? View the recording here.

Thanks again to our amazing panelists!

Emily is a seasoned nonprofit and social impact expert with 14 years of experience leading social justice organizations and programs from community to global levels. She specializes in program innovation and design, strategy and leadership, facilitation, and peer learning. Among Emily’s career highlights, she has served as Executive Director of a grassroots women’s rights and anti-violence organization in British Columbia, Canada; spearheaded global peer exchange networks and innovative women’s leadership programming; and designed cutting-edge participatory research about GBV in remote and Native communities.

Originally published at Collective Mind

Featured image found here

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

From Learning to Doing

Many years ago I was teaching high school English on a small island in SE Alaska. I asked the class to compare a piece of literature to the story of the Three Little Pigs. Half of the class couldn't do the assignment because they had never heard of the story of the Three Little Pigs. That changed me forever.

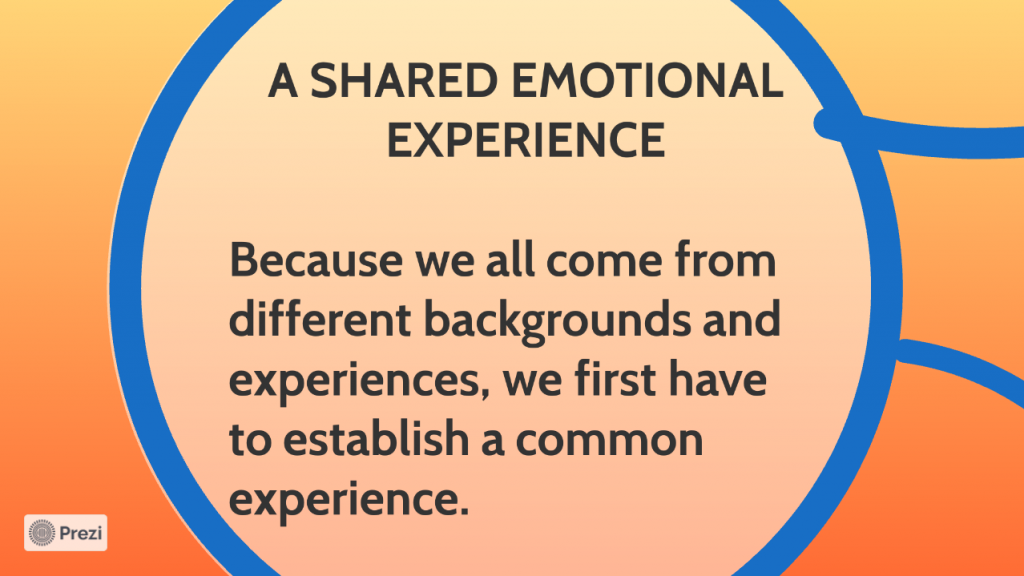

Without shared experiences, learning communities often talk past each other. Inevitably there is a judgement on one side or the other. Each learner brings his/her own experiences to a conversation and uses those unique experiences to make sense of things. Coming together as a learning community to sort through what we understood from something new that is introduced to us is sometimes very frustrating because of all the different experiences brought to the table. To help with that issue in almost any learning community, you can initiate a common experience/action for all participants. When an action is experienced together, suddenly there is more justice in the conversation. The playing field is leveled and the real conversation can begin.

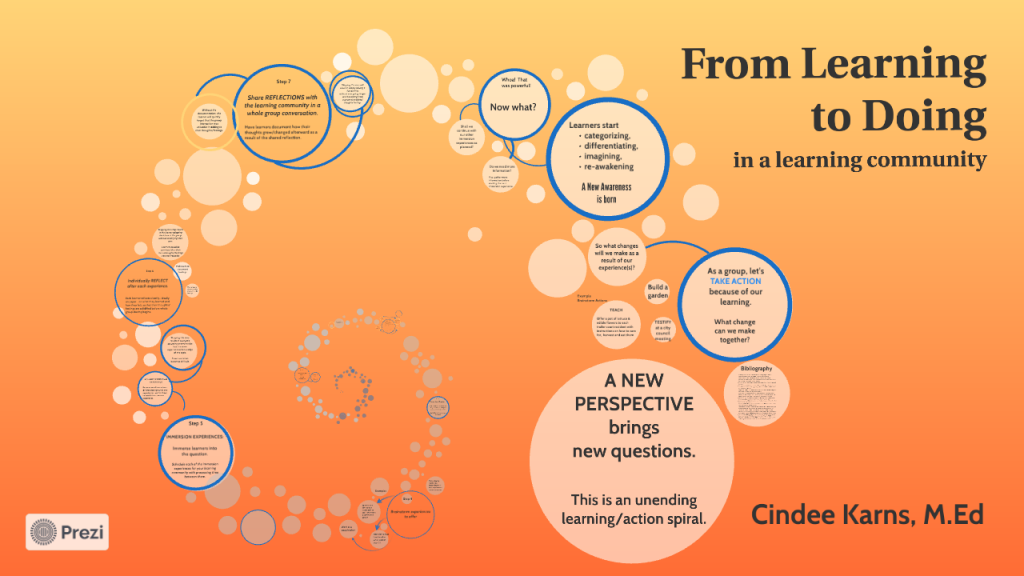

This is a depiction of how that process can be set up for any learning community. The condition is that the learning spiral never ends....every round goes higher, higher. The outcome is that participants almost always feel like they can act on their new knowledge and continue the learning cycle on their own.

Click HERE to access the "From Learning to Doing" resource. A slide presentation on how to create shared experience in a community to initiate actionable change.

Click HERE to access the slide show directly at prezi.com

Cindee Karns, a life-long Alaskan, is a retired middle school teacher with a master's in Experiential Learning. She is founder/weaver of the Anchor Gardens Network, which is attempting to bring increased food security to Anchorage. She and her husband live in and steward Alaska's only Bioshelter

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

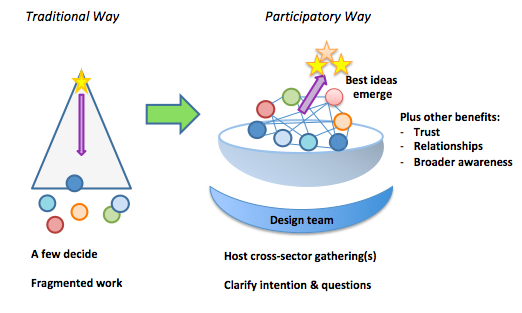

MAKING LARGE EVENTS PARTICIPATORY

This blog was originally published in October, 2019, when we couldn’t foresee that most large events would cease. As we anticipate meeting again in person, I hope the approaches here give you ideas. You might like to check out my new meeting design coaching services.

It’s possible to make large events participatory and interactive. Here we share our latest inspiration and approaches, from recent work with events from 50 people to over 200 people. The topics and audiences vary, yet the desire to inspire and connect people, enhance learning, build connections, and advance work beyond the meeting is the same. Here’s what goes into our secret sauce for creating a participatory, inspiring event:

Participation starts in design: Working with a design team that includes representatives of the people who will be participating in the event helps ensure the event format is relevant and effective. This group can:

- Bring varied perspectives to clarify the context and conversations that are needed now. For example, with a state-wide food network that’s been underway for five years, we landed on this strategic question: How can the structure and approaches of the network galvanize and support action and momentum at the local, regional, and state levels? It took some thinking and conversation to get clear that this was the most powerful question for this moment. We brought in case studies to spark the conversations.

- Provide input on the format of the meeting and who to invite and how, e.g., you can access the broader social and professional networks of those in the room to learn about other people, organizations, and initiatives who could be invited.

- Serve as ambassadors for the vision and the meeting/initiative, spreading the word, helping with invitations, and sharing feedback they are hearing.

For example, we co-facilitated the annual meeting of the Greater Nashua Public Health Network, with a focus on building a trauma-informed community. The design team helped us get a sense of how much training had been done so we could tailor the content of the training portions. We agreed on a clear set of desired outcomes and went through several rounds of an agenda design, tailoring and improving it each time, based on their feedback.

At the event, start with stories: Getting people sharing stories early in the day builds relationships and creates a warm, welcoming environment. Our approach is inspired by an exercise called Radical Acceptance, which I learned from taking improv classes with Boynton Improv Education in Portsmouth, NH. This simple exercise builds a sense of emotional safety and encouragement for everyone to speak up. I modified it slightly by doing the following:

- At round tables, invite each person to introduce themselves and share one brief story of something going well in their work. Invite everyone to respond with a “yes!” or any other enthusiastic positive response. Then the next person goes and the group does the same. Across the room you hear “yes!” and clapping and laughter, and see fist bumps.

- In another variation at the Nashua meeting, we asked each person to share one thing they appreciate about Nashua/the region and put it on a post it note. We used the same process I mentioned and then collected these and had a graphic facilitator make a poster of the themes.

This only takes 10-15 minutes. Sometimes people pick up on the “yes!” and bring that positive response into other parts of the day, often with a shared laugh.

Offer inspiration/new ideas and new voices: Beyond the standard keynote presentations and skill-building workshops, consider having shorter TED-talk type or PechaKucha presentations (presenter has about 7 minutes to talk with 20 image slides) and featuring voices beyond “experts,” e.g., youth, those with lived experience, people from marginalized identities or communities.

Host cross-pollinating small group conversations: The World Café process taps the ideas of everyone in the room and allows people to make new connections and learn from each other. At an anti-racism gathering of 200+ people from Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, we invited people to talk in a group of four with people from their state about what is working in anti-racism work. In the second round, they mixed to a new group of four with people from other states, sharing themes from the previous conversation, and then talking about what more was needed. With 200 people, this meant we had 50 four-person conversations each round (100 total), which is a lot of learning and information exchange…and fertile ground for new relationships and collaborations to form.

Allow space for self-organized deeper dive conversations: All of the conversations and ideas percolating through the first part of an event can be given a space to land and deepen if you design space for that. Inspired by the process of Open Space, here’s an example of how we organized this at the event with 200 people:

- During the morning sessions, we asked people to submit topics they’d like to discuss with others at an Open Space/deeper dive conversation session that afternoon.

- Over lunch, we grouped these into about 16 overall topics. I made folded table tents with a table number and name of the topic and put these out on the round tables. I sketched a chart showing table numbers and topics, took a photo, and put it up on a slide.

- When that session began, I invited people to join the topic they’d like to discuss and walked around with a roving microphone to introduce the topics and show which table was where, with the slide image as another guide.

- We asked for a note-taker at each table. For topics where lots of people showed up, we invited them to split into several tables. At the end, we heard brief highlights from the table conversations.

At another event, we had time for people to rotate to a second topic table, while some people stayed at the first one, building in another layer of connection and cross-pollinating.

The range of topics that were suggested were far beyond what our design team would have thought of, and we learned which areas had the most interest. People had the freedom to initiate or join conversations and connect with others with similar ideas, concerns, and questions.

I wish I could somehow visualize and learn all the seeds that got planted at these events. We offered the fertile ground – so time will tell what grows!

Beth Tener is a leadership trainer and coach who helps social change leaders live their values as they address complex challenges, such as transitioning to a clean energy economy, disrupting racism, and revitalizing communities. She is passionate about bringing people together in ways that unlock and ignite personal, group, and community potential. She is the founder of New Directions Collaborative, based in Portsmouth, NH, and has worked with over 200 organizations and collaborative networks.

originally published at New Directive Collaborative

featured image found here

Being a strange attractor

This article forms the first in an intended series of articles. The main theme of that series is to reflect on a new language for social transformation. For me, language goes beyond words, concepts or metaphors. Essentially, it is the filter through which we look on life, perceive our environment and plan our actions. Changing our language, therefore, is a powerful way towards personal and collective transformation.

Every article of the series is dedicated to a specific theme or concept. Yet, rather than enriching your vocabulary, it is much more the shift in perspective underneath the concept that I want to contribute to. In our case, strange attractors are a concept from chaos theory. Exploring strange attractors are therefore a gateway into the world of chaos, dynamical systems and complexity. And what is a strange attractor?

Well… there is no simple answer. But I have an idea where to start.

To enable non-linear reading I visualised the article on kumu as a dynamical map:

The starting point

Life puzzles me. Partly my own. Even more so fundamental questions like how life emerged? Or human sense-making: how on earth is it even possible that we can communicate? I jot down these black & white symbols on a keyboard, they appear on a screen and you can understand what I am trying to say.

In a similar way: given the goodness and well-intendedness of many of us, how are we able to create phenomena like environmental destruction? What social and psychological principles are at play in our daily lives that enable outcomes we don’t want?

The reasons for asking myself these questions are twofold: I have a genuine curiosity to go to the bottom of things, wanting to understand the root causes rather than superficial appearances. Understanding for its own sake so to speak.

And then there is this undeniable desire to drive social change. I came here for a reason. Not to accept what is happening around me, but to play an active role in co-creating our future. This part of me is highly intentional, using knowledge to identify leverage points for personal and social transformation. More specifically, I am eager to learn and embody how I can contribute to meaningful change.

In the past years, those motivations (or better: driving forces) lead me down some rabbit holes, both in theory and practice.

Embarking on a journey into strange lands

Due to my fascination for social change, it is not such a surprise that I studied sociology. There, most approaches and (meta) theories are relatively systematic, with the ambition to explain and the tendency to categorise. It is difficult to speak about the diverse field of sociology in general terms. Yet what I often found was theories and methods that made sense of events once they happened. Categorising the past and projecting it into the future. And then making those events fit the theory. It reminded me of the story of the little prince, visiting the king on his planet*:

Little prince: “Sire–over what do you rule?”

King: “Over everything,” said the king, with magnificent simplicity.

[…] Little prince: “And the stars obey you?”

King: “Certainly they do,” the king said. “They obey instantly. I do not permit insubordination.”

Little prince: “I should like to see a sunset … Do me that kindness … Order the sun to set…”

King: “You shall have your sunset. I shall command it. But, according to my science of government, I shall wait until conditions are favorable.”

Little prince: “When will that be?” inquired the little prince.

King: “Hum! Hum!” replied the king; and before saying anything else he consulted a bulky almanac. “Hum! Hum! That will be about– about– that will be this evening about twenty minutes to eight. And you will see how well I am obeyed.”

I was curious to find out if there is more. My backpack filled with Weber & Elias, Luhmann & Habermas, Foucault & Bourdieu, Berger & Luckmann I expanded my search for answers; and wandered off into the strange lands of complexity science, chaos theory and fractal geometry. For me, those excursions have not only been fascinating from an academic perspective, but also insightful for my life as a social entrepreneur. I invite you to come with me and discover those strange lands. And I promise that I will guide you back at the end.

What’s the weather like over there?

Welcome in the world of complexity! As with most other foreign places, things work a bit differently here. Let’s start with a quick introduction first: As James Gleick in his groundbreaking book “Chaos. Making a new Science” put it:

“the act of playing the game has a way of changing the rules”

If you want it or not: as soon as we arrive at the shores, we are not merely passive visitors. We are active agents and influence what is happening here. A complex system, therefore, is dynamic and adaptable. It responds to its environment yet has its own “agenda”. The question, then, is what provides orientation for the behaviour of the system and the actors within it? The answer: Strange attractors!

Some of us may be familiar with pictures like those:

CC BY-SA 3.0.

It shows the so-called Lorenz attractor. It describes visually how a dynamical system behaves, in this particular case the flow of fluid under certain conditions. The attractor itself is “the whole thing”, the space that spans all potential behaviour. We can see that there are two central attractor points around which the system seems to rotate. The strange thing is that – despite having knowledge about all relevant parameters – it is impossible to predict how the system will evolve over time. This is called nonlinearity. Caused by those weirdly arranged attractors.

As an analogy, you can imagine the weather: Weather with all its components (temperature, air pressure, humidity etc.) is the system. If we measure those components and visualise them, we get our (visualised) attractor of the system; most likely indicating us certain central points. In most geographical locations, there are two main states, summer (dry season) or winter (rainy season). Let’s say “summer” is the attractor state on the left, “winter” on the right. Any day of the year constitutes a point. Usually, we know if it’s summer or winter, and how the next days will roughly be like. Yet any precise prediction beyond 10 days is almost impossible. And at some point, the system will shift. We know it will happen, yet we don’t know the exact day. No matter how much information we have at hand.

As our nerdy friends would say: The weather is a chaotical & nonlinear system. Its behaviour rotates around two central attractor states. This leads to the fact that the system is locally unstable yet globally stable. That’s quite strange, yes. But what does that have to do with social transformation?

To me it seems that societies, communities, families (put any social system you like here) rotate around certain states as well. Conservative or liberal, open or closed to “outsiders”, free markets or state-centred economies. Those systems experience periods of prolonged stability (economic growth with prosperity), followed by a rapid & sometimes unexplainable “switch” (the dotcom or housing bubble bursting). Looking with that lens on my environment has helped me a lot to understand social change. Order and chaos should not be seen

“as antagonistic and fixed states but rather as stages in a process of dynamic and transformational becoming”.

― Elisabeth Garnsey and James McGlade

The same accounts for any dynamical system with more than one equilibrium, more than one attractor state so to speak.

The dance between polarities

Butterflies have two wings. We have winter and summer (or rainy and dry season). There is life and there is death. Following those examples, polarities seem to unite stability and movement. In that sense, opposites are not really opposing each other. They create space for life to happen in between.

“The only way to make sense out of change is to plunge into it, move with it, and join the dance.”

― Alan Watts

We tend to care about what happens around us; and oftentimes have the desire to influence it in a certain way or direction. Joining in the dance does not mean to accept everything that happens. Rather, it means to understand that it is the underlying rhythm that moves us. To change the dance, we have to change the music (or the polarities in our case).

Taking the principle of nonlinearity into account, there are ways to make a certain behaviour (of a system) more likely, orientating it towards a (desired) attractor state. Yet, despite our best efforts, we can never know what will actually happen. Life is unpredictable. But life is not random either.

And we have a true super-power on our side. Social systems differ from the weather in one important aspect: the attractor states are social constructions. They are based on language and culture, on individual and collective agency. And what was constructed once by people can be changed. In other words: We have the capacity to create and establish new attractors.

The attractors of our time

“Grown-ups love figures… When you tell them you’ve made a new friend they never ask you any questions about essential matters. They never say to you “What does his voice sound like? What games does he love best? Does he collect butterflies? ” Instead they demand “How old is he? How much does he weigh? How much money does his father make? ” Only from these figures do they think they have learned anything about him.”

― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Translated into a social context, we can see an attractor state as a shared set of beliefs and internalised symbols and habits. A fix point within a certain system like family or economy. The word “purpose” comes relatively close to it. Let’s examine what the current attractor states of our society are. For the sake of length and digestibility, we will keep it short, unscientific and subjective.

Western thought is highly influenced by the idea of a mechanical universe (Newton) and mind (Freud). It emphasises the difference between an individual and its environment, and the differences between people. The centre of this worldview, then, is the autonomous and isolated individual.

“I, a stranger and afraid

In a world I never made.”

― A.E. Housman, Last Poems

As we know, attractors stabilise behaviour. The attractors emerging out of this particular worldview are economic growth & meritocracy as well as the attempt to control our environment (which includes both our natural and social environment). It is a paradigm of competition, of “me/us against”. As a consequence, we usually only focus on one side of the polarity; the side that we prefer and desire. And we pathologize the other side. Economic growth is good, de-growth is bad. Being happy is desired, depression is something we have to treat with medication. It’s like wanting to breath in all the time, judging all the outbreaths.

Still, orienting our behaviour towards those states brought enormous prosperity (for some) and stability. We live in an era of unseen peace, economic wealth, scientific discovery and global interconnectedness. Yet something is off. It feels like our own inner attractors (our personal purpose, our desire for integration and wellbeing) pull us away from society’s inner attractors. The tricky thing is that both types of attractors – individual and collective – are usually invisible. Usually.

“And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

From opposition to integration

We are still in the land of complexity, remember? We learned that here, attractors of a system are not seen as opposites. On summer follows winter, follows summer, follows winter. The system is healthy when it shifts between both states. This leaves us with the question:

What are healthy polarities for us as society?

Let’s look at an example that some of us (me for sure) struggle with: balancing working and resting / free time. An alternative way to phrase it could be: Creating something specific (for others) vs. taking care of yourself only. The current paradigm likes to phrase that as “work-life balance”, one of the most horrible terms I know. As if working would not be part of my life. The underlying polarity is “being productive vs. allowing yourself time to be unproductive”. In a more mechanistic view to drive the point home: running the machine vs. oiling the machine. (with the addition that even “unproductive” time is often turned into a product – like consuming advertisement).

That’s not a healthy attractor to me. And I see myself falling into this polarity if I am not careful and attentive. An alternative way of phrasing it would be: I am enjoying my time either creating something meaningful for other people (a.k.a. working) or I enjoy to just do things for their own sake. In this way, the mechanistic attractor (work vs. life) is replaced by a more wholesome attractor (meaningful and intentional action & enjoying things simply for themselves). It’s still two polarities, yet they don’t oppose each other.

In a similar fashion, we can look at our climate crisis. We live on the expense of our environment. And this challenge cannot be solved with simplistic regulations or public claims that keep the idea of economic growth alive. No, the paradigm of economic growth is not compatible with environmental survival. It does not work to simply include nature into this growth-logic (calling it sth. like green technology). We need new polarities, new attractor states to address this challenge. An economic attractor that allows certain elements to be outside of the linear growth logic. What this could be I leave up for your imagination.

Sounds idealistic? Well, I would call it pragmatic imagination. As all we see around us was an image in our heads first, then turned into “reality”. One invitation I see here is to move away from a paradigm of needing to know and control, rather framing the attractor around a central question. How can we integrate work and free-time into a fulfilling life? How can we assure both our material wellbeing and the wellbeing of the nature that surrounds us? It’s OK to not have the answers (attractor states) yet. But we can (re)frame the attractor around them.

In this, the world desperately needs individuals who are capable of transcending the worldview of opposites, black and white, gain and loss, good and bad. A world of scarcity and competition. Not just conceptually, but with our actual behaviour and actions.

“We but mirror the world. All the tendencies present in the outer world are to be found in the world of our body. If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. We need not wait to see what others do.”

― Mahatma Gandhi

Strange attractors of this world, unite!

Are you seeking to create a future for yourself and others that is different from the present? As an activist, social entrepreneur, philanthropist, parent, consumer …? Then I would consider you as a change agent, or strange attractor. Somebody who inspires and motivates themselves and others to act on a worthy ideal. A strange attractor in that sense can be any individual, but also an idea, a startup or a movement we represent.

We may be far out in the old paradigm, and it is frustrating from time to time. But we can constitute the centre points in the new paradigm. We are the ones to create new attractor states for our common future.

So how can we do that?

I see two crucial steps to make this happen. And you may have guessed already: Number one is to be the strange attractor yourself. Be the space and inspiration for others. Embody a new path for action. Number two is to team up and create (new) social systems jointly. Both steps are courageous and bold. And here is why:

Embodiment is not only an intellectual exercise. Here I speak out of tough personal experience: Stating that I want to achieve something (e.g. to be a humble and inspiring leader) often created distance. Rather than motivating me, it made me (subconsciously) believe that I am not there yet. Doing the inner work is required. Knowing and accepting ourselves. Embracing our inner beauty, shadows and power. And there are no quick fixes or shortcuts.

Teaming up is even more delicate. It requires us to find each other, create thriving teams, organisations and networks. In short: institutionalise new attractors. Probably this will cause opposition. From others and from within. As it requires us to let go of our individual dreams to form collective ones.

My answer to that is: yes, that’s quite a task, but what else should we do? What else are we here for?

Jannik Kaiser is co-founder of Unity Effect, where he is leading the area of Systemic Impact. His desire to co-create systemic social change led him down the rabbit holes of complexity science, human sense-making (e.g. phenomenology), asking big questions (just ask “why” often enough…) and personal healing. Having worked in the NGO sector, academia and now social entrepreneurship

Originally published at UnityEffect.net

The Web of Change

Creating Impact Through Networks

The following post is excerpted from the introduction of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change, now available in print, as an audiobook, and as an ebook.

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

— Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Since the beginning of our species, humans have formed networks. Our social networks grow whenever we introduce our friends to each other, when we move to a new town, or when we congregate around a shared set of beliefs. Social networks have shaped the course of history. Historian Niall Ferguson has noted that many of the biggest changes in history were catalyzed by networks—in part, because networks have been shown to be more creative and adaptable than hierarchical systems.[1]

Ferguson goes on to assert that “the problem is that networks are not easily directed towards a common objective. . . . Networks may be spontaneously creative but they are not strategic.”[2] This is where we disagree. While networks are not inherently strategic, they can be designed to be strategic.

When deliberately cultivated, networks can forge connections across divides, spread information and learning, and spark collaborative action. As a result, they can “address sprawling issues in ways that no individual organization can, working toward innovative solutions that are able to scale,” write Anna Muoio and Kaitlin Terry Canver of Monitor Institute by Deloitte.[3] Networks can be powerful vehicles for creating change.

Of course, networks can have positive as well as negative effects. Economic inequality and the advantages and disadvantages of social class, race, ethnicity, gender, and other aspects of individual identity are in large part the result of network effects: certain types of people form bonds that increase their social capital, typically at significant social expense to those in other groups. Much of the world has become acutely aware of the harmful network effects arising from social media and the internet. This includes the proliferation of online echo chambers that feed people what they want to hear, even when it means rapidly spreading misinformation.

In our globally connected and interdependent society, it is imperative that we understand the network dynamics that influence our lives so that we can create new networks to foster a more resilient and equitable world. The choice in front of us is clear: either we can let networks form according to existing social, political, and economic patterns, which will likely leave us with more of the same inequities and destructive behaviors, or we can deliberately and strategically catalyze new networks to transform the systems in which we live and work.

A case in point is the RE-AMP Network, a collection of more than 140 organizations and foundations working across sectors to equitably eliminate greenhouse gas emissions across nine mid- western states by 2050. From the time it was formed in 2015, RE-AMP has helped retire more than 150 coal plants, implement rigorous renewable energy and transportation standards, and re-grant over $25 million to support strategic climate action in the Midwest. RE-AMP’s work is necessary in part because other powerful networks are also at play to maintain the status quo or to enrich the forces that profit from pollution and inequality.

We can look to the field of education for another example of a network creating significant impact. 100Kin10 is a massive collaborative effort that is bringing together more than three hundred academic institutions, nonprofits, foundations, businesses, and government agencies to train and support one hundred thousand science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) teachers across the United States in ten years. Founded in 2011, 100Kin10 is well on track to achieve its ambitious goal and has expanded its aim to take on the longer-term systemic challenges in STEM education.

The Justice in Motion Defender Network is a collection of human rights defenders and organizations in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua that have joined together to help migrants quickly obtain legal assistance across borders. Throughout the ongoing family separation crisis created by US immigration policies during the Trump administration, this network has been essential in locating deported parents in remote regions of Central America and coordinating reunification with their children.

Or consider a network whose impact spans the globe, the Clean Electronics Production Network (CEPN). CEPN brings together many of the world’s top technology suppliers and brands with labor and environmental advocates, governments, and other leading experts to move toward elimination of workers’ exposure to toxic chemicals in electronics production. Since forming in 2016, the network has defined shared commitments, developed tools and resources for reducing workers’ exposure to toxic chemicals, and standardized the process of collecting data on chemical use.

Networks like RE-AMP, 100Kin10, the Defender Network, and CEPN—along with many others you will learn about in this book—were not spontaneous or accidental; rather, they were formed with clear intent. These networks deliberately connect people and organizations together to promote learning and action on an issue of common concern. We call them impact networks to highlight their intentional design and purposeful focus, and to contrast them with the organic networks formed as part of our social lives.[4]

We think of impact networks as a combination of a vibrant community and a healthy organization. At the core they are relational, yet they are also structured. They are creative, and they are also strategic. Impact networks build on the life force of community—shared principles, resilience, self-organization, and trust— while leveraging the advantages of an effective organization, including a common aim, an operational backbone, and a bias for action. Through this unique blend of qualities, impact networks increase the flow of information, reduce waste, and align strategies across entire systems—all while liberating the energy of multiple actors operating at a variety of scales.

All around the world, impact networks are being cultivated to address complex issues in the fields of health care, education, science, technology, the environment, economic justice, the arts, human rights, and others. They mark an evolution in the way humans are organizing to create meaningful change.

To learn more about what impact networks are, how they work, and what it takes to cultivate and sustain them, check out the new book Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change.

[1]: Niall Ferguson, The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power (London: Penguin Books, 2018), xix.

[2]: Ferguson, The Square and the Tower, 43.

[3]: Anna Muoio and Kaitlin Terry Canver, Shifting a System, Monitor Institute by Deloitte, accessed December 17, 2020, https://www2.deloitte.com /content/dam/insights/us/articles/5139_shifting-a-system/DI_ Reimagining-learning.pdf.

[4]: June Holley has called them “intentional networks” in Network Weaver Handbook: A Guide to Transformational Networks (Athens, Ohio: Network Weaver Publishing, 2012). Peter Plastrik, Madeleine Taylor, and John Cleveland have called them “generative social impact networks” in Connecting to Change the World: Harnessing the Power of Networks for Social Impact (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2014).

Originally published at Converge

David Ehrlichman is a catalyst and coordinator of Converge and author of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change. With his colleagues, he has supported the development of dozens of impact networks in a variety of fields, and has worked as a network coordinator for the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network, Sterling Network NYC, and the Fresno New Leadership Network. He speaks and writes frequently on networks, finds serenity in music, and is completely mesmerized by his newborn daughter.ehrlichman@converge.net

Critical support for network leaders and managers