Learning about Change and Transformation

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]Co-Design Series Part 4[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]

Most of you reading this post are involved in what are called social change efforts. We are working on social change because we want the world to be full of communities that are good for everyone. But the reality is that our communities are full of problems - poverty, drugs, intolerance, etc - and most of us are working diligently to try to crack open these problems and find solutions.

What is amazing is how little time we actually spend thinking about change - how it happens, how it can be supported, how to increase it and most importantly, how to make it transformative.

Increasing numbers of us know that what it is going to take is not simple incremental change but transformation - shifting the systems in which these problems are occurring.

Transformation means changing the way our society operates so that it reflects healthy values: this means that all our institutions, our processes, our interactions are open and transparent, inclusive and diverse, innovative and experimental, where power is equally distributed, and we work collaboratively together.

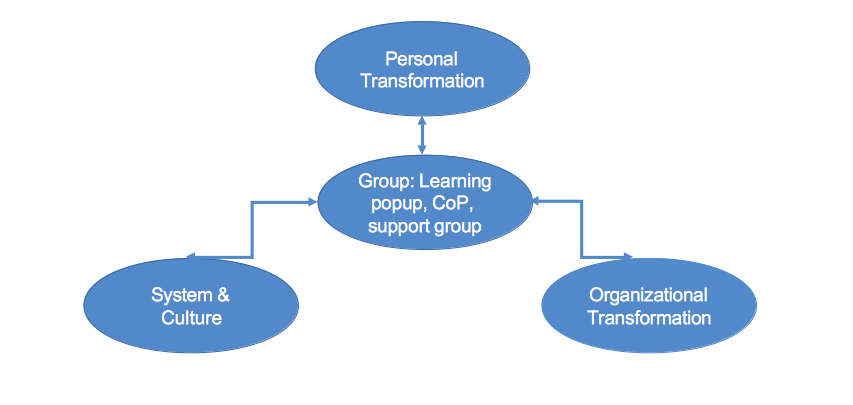

But transformation doesn't just happen on the system level. Transformation needs to occur on every level: at the same time we are working to change institutions such as the prison system we need to be working on personal change and on organizational change.[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Diagram 1. Groups help us change on other levels

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

If we don't change as individuals - our mindset, the way we interact with others and who we interact with - we’re not going to be able to work well with others to shift the systems. And it's only when we begin to interact with others who have different perspectives that we are able to see the hidden assumptions we have been making that have been keeping our efforts from leading to systemic change,

For example, if we are trying to develop strategies to end poverty and we don't have any people who are actually living in poverty in the room with us figuring out the best way to address poverty, we will be unlikely to come up with solutions that will be more than a Band-Aid on the complex and massive problem that poverty represents.

And, we won't get other people in the room with us unless we change and become better listeners, more open to new ideas, and more willing to let go of control.

Another example of why it's so critical that we change as individuals is because our endless “to do lists” are holding us prisoners and keeping our work from being transformative. When June worked with people as an executive coach, they discovered that their to do lists were filled with items that were nonessential. These nonessentials distracted people from spending time on stepping back from their work as a whole. It's only when people learn to scrutinize and prune their to do lists that they have time to reflect on what they're really doing and notice what works and what isn't. (see Worksheet: Freeing up your time for transformation Free in Resources Section)

What keeps us from changing? We need to become more aware of our behavior so that we remember to change. Personal assessments or checklists and then daily journaling are helpful tools for change. How can we encourage more people to incorporate these into their daily lives?

But let’s face it, change is hard to do alone. We need the support of others to help hold us accountable, listen to our challenges, and give us ideas for strategies. Small support groups or learning pop-ups are very beneficial for personal change, and they can support us as we work to change our organizations.

And, when we change ourselves, but don’t simultaneously help our organizations transform, we will continually run up against obstacles in our work. For example, many organizations see time spent on building relationships with those outside the organizations as a waste of time rather than an important step in network building and discourage or forbid their employees to network. Or, our manager insists on getting approval from her/him for the action steps we take in collaborative projects with other organizations, thus slowing down responses to opportunities that arise.

One of the best ways to change both ourselves and our organization is to be part of small groups where people help each other change. These can be support groups, learning pop-ups or communities of practice (monthly sessions where people share skills and provide support for each other around challenges that they face in getting their organizations to shift to a network mindset). In addition, working with others on self-organized projects related to our work can be a powerful way to shift behavior.

Networks can also set up friendly fun systems to enable us to identify where we want to change, help us get ideas for how we can change, and get feedback on those changes.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Read Part 1 of the Co-Design Series HERE

Read Part 2 of the Co-Design Series HERE

Read Part 3 of the Co-Design Series HERE

Appreciative Reflections

I have a number of ‘network friends’ – people I know, online & by video & phone, whom I’ve not yet met in the flesh. People who for one reason or another, reached out to me, or I reached out to them, knowing by our online presence & by our shared connections to others that we had something to learn together.

In this growing field of ‘Network Weaving’, it’s easy to connect quickly & begin to share work, ideas, resources and to bond in a real way, with people we’d normally consider strangers.

One of the women I’ve connected to in this way just shared something with me that she’s been working on. A beautiful contribution to our field that she’s been toiling away on so long she’s lost track, a little bit, of the value & beauty in it. As I affirmed & appreciated her efforts via email, she reflected me back to myself in a way I aspire to, but, honestly, I DO NOT know what causes her to see me in that way. She sees the me I’d like to be, but don’t identify as self.

As I began to write a reply email, saying that I’m honored by how she sees me, even tho I cannot see myself the way she does, this struck me:

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

When we connect & share & trust & honor, we begin to see the strengths, beauty, & potential in one another that we can’t entirely see in ourselves. And when we voice those things we see in one another, we help bring them into being even more.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Her words made me feel SEEN, recognized. Which inspires and en-courages me to be more of what she saw, even if I’m not entirely sure what allowed her to see it.

No doubt this seems elementary to good parents & teachers (I mean, as a parent, that power to bring out the best in my son by simply reflecting him back to himself was awe-inspiring) – but there was a new epiphany in it, for me, today.

So – here’s the part that was striking in the moment – what we see in each other, and call out in one another – becomes the very source of transformation. A greater belief in our gifts increases our ability, willingness & desire to give of them. Seeing one another’s gifts brings about more of those gifts. Feeling valued and recognized also increases our willingness to collaborate, our openness to others, our ability to journey together into the unknown.

System change & saving the world are hard work that many people want to be part of. But over and over, we hear how people are just below their breaking points, stretched to their limits, overwhelmed with how much effort it takes just to maintain. They can’t take on even one more small commitment. But when the efforts that align with our passions or express our deepest selves are met with affirmation & encouragement, what we do becomes a little less effortful, we regain energy faster, we contribute again sooner and more. Recognizing & affirming each other, in a change network, can be one of those small shifts that bring about huge changes.

As a traumatized hyper-vigilant welfare brat, I’ve usually been highly suspicious of compliments or kind words, and have spent much of my life pushing them away.

But lately I’ve been learning, in very tangible ways, how our piling on sincere appreciation & authentic recognition of one another not only heals & encourages at the individual level, it fuels collective transformational ripple effects.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]For Mary Roscoe for inspiring this reflection and for Michael Bischoff, for seeing the true me into being.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]Originally published May 16th, 2016 by Christine Capra at GreaterThanTheSum.com

Criteria For A Design Process Emerging From Network Values

[ap_spacing spacing_height="35px"]Co-Design Series Part 3[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]

First, we wanted to make sure our definition of co-design fit our list of network values.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]1) The co-design process needs to create an alternative to the inevitable unequal power found in a conventional design process. Participants must be peers with the designers not just subjects of inquiry. Designers must recognize, honor, and center the true expertise needed to design the product - that of the participant/user. Participants should have equal weight in designing and determining the end products that the design process creates. Ask, Does everyone feel like their expertise, experiences, and contexts are valued?

Cea and Rimington describe 5 ways to equalize power in a design process:

- define the problem at hand with the others involved

- trust all players with full information about the big picture of the project and the constraints

- support authentic leadership roles and structures for participants

- create an environment that incentivized decentralization of creative input and power

- encourage fluid roles.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]2) To underscore trust and promote deep learning, we think the design process should develop long-term relationships between designers and users. This moves everyone involved from transactional relationships to those that can be transformative. For this to happen, we cultivate relationships that support vulnerability and truth-telling. Furthermore, these deeper, more honest and peer like relationships will strengthen the overall network: any codesign process is a network building process. Ask, “Do people feel comfortable sharing their true opinions of the process and product?”

[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]3) Next the process must have maximum engagement of the participants who will be impacted by the product or who are interested in the design process to develop the product. This suggests moving beyond focus groups to having more rigorous, regular feedback on prototypes; literacy needs to be developed in everyone to understand contexts, technical terms, and experiences. People need to have opportunities to engage in different venues (one-on-ones, small groups, full group convenings). Ask, "Are people excited to engage?”

[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]4) The process must value difference and diversity of perspectives. This means that many different kinds of people - young and old, people from different backgrounds - are included. This is critical because it is diversity that leads us to question our assumptions and think differently about design. We like the term productive conflict. Ask, “How can differences let us see a new way of looking at things?”

[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]5) Everyone involved in the process needs to understand that the product development process is iterative. Any design is in perpetual beta. We need to be continually involved in gathering feedback and using it to transform the products that we co-create. Ask, “Is there energy for continued conversations about the product or process?”

[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]6) In most cases, the initial design team will involve a limited number of participants of the network - even if it uses participative processes. However, part of the design process needs to be strategizing how each design participant can introduce and share the product with others in their network so that the product goes viral. Ask, “Does everyone in the network have a chance to try out the new product to determine usefulness?"

[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]7) The design process is also an opportunity for participants to learn how to conduct co-design processes in their organizations and local networks. Ask, “Does the design process provide time to help participants integrate co-design into all network processes?”[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]

Read Part 1 of the Co-Design Series HERE

Read Part 2 of the Co-Design Series HERE

25 Behaviors That Support Strong Network Culture

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]“Only connect! That was the whole of her sermon. Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer.”

E.M. Forster, from Howard’s End

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]This is an excerpt from the final post in a series of five focused on networks for change in education and learning that have appeared on the Education Week and Next Generation Learning Challenges websites.

In this series on network design and network thinking, I explored the power and promise of networks as residing in how connection and flow contribute to life, liveliness and learning. See, especially, Connection is Fundamental.

In Why Linking Matters, I looked at how certain networks can more optimally create what are known as “network effects,” including small world reach, rapid dissemination, resilience, and adaptation.

I also noted, in Structure Matters in particular, that living systems–including classrooms, schools, school districts, and communities–are rooted in patterns of connection and flow. That’s why shifts in connections–between people, groups, and institutions–as well as flows of various kinds of resources can equate with systemic change, and ideally they can lead to greater health (in other words, equity, prosperity, sustainability).

Networks can also deliver myriad benefits to individual participants, including: inspiration; mutual support; learning and skill development; greater access to information, funding, and other resources; greater systemic or contextual awareness; breaking out of isolation and being a part of something larger; amplification of one’s voice and efforts; and new partnerships and joint projects.

It’s also true, however, that not every network or network activity creates all of these effects and outcomes. The last two posts looked at two factors that contribute to whether networks are able to deliver robust value to individual participants and the whole, including network structure and what form leadership takes. Networks are by no means a panacea to social and environmental issues and can easily replicate and exacerbate social inequities and environmentally extractive practice. So values certainly have a place, as does paying close attention to dynamics of power and privilege.

It is also the case that individual and collective behavior on a day-to-day basis have a lot to say about what networks are able to create.

The following is a list of 25 behaviors for you to consider as part of your network practice as an educator:

- Weave connections and close triangles to create more intricacy in the network. Closing triangles means introducing people to one another, as opposed to networking for one’s own self, essentially a mesh or distributed structure rather than a hub-and-spoke structure.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Create connections across boundaries/dimensions of difference. Invite and promote diversity in the network, which can contribute to resilience and innovation.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Promote and pay attention to equity throughout the network. Equity here includes ensuring everyone has access to the resources and opportunities that can improve the quality of life and learning. Equity impact assessments are one helpful tool on this front.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Name and work with power dynamics and unearned privilege in the direction of equity.

- Be aware of how implicit bias impacts your thinking and actions in the network. Become familiar with and practice de-biasing strategies.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Think, learn, and work out loud, in the company of others or through virtual means. This contributes to the abundance of resources and learning in the network.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Don’t hoard or be a bottleneck. Keep information and other resources flowing in the network.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Identify and articulate your own needs and share them with others. Making requests can bring a network to life as people generally like to be helpful![ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Stay curious and ask questions; inquire of others to draw out common values, explicit and tacit knowledge, and other assets.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Make ongoing generous offers to others, including services, information, connections.

For behaviors 11-25, see this link.

“… Keep reaching out, keep bringing in./This is how we are going to live for a long time: not always,/for every gardener knows that after the digging, after/the planting, after the long season of tending and growth, the harvest comes.”

Marge Piercy, from “The Seven of Pentacles”

Originally published on May 17, 2018 at Interaction Institute for Social Social Change.

Why Dismantling Racism and White Supremacy Culture Unleashes the Benefits of Networks

Before we go any further down the road of this blog, we need to point out that network approaches cannot become transformative unless the network explicitly works on dismantling white supremacy culture and racism.

This is because networks only flourish when people in them are able to interact as peers, valuing everyone’s input and involvement. In addition, many aspects of dominant or white supremacy culture hold us back from reaping the benefits of networks, but are so pervasive as to be hidden from our awareness. Tema Okun has one of the best lists of these cultural characteristics which include (the next two sections are quoted verbatim from her article):[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

1. Perfectionism

- Little appreciation expressed among people for the work that others are doing; appreciation that is expressed usually directed to those who get most of the credit anyway[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- more common is to point out either how the person or work is inadequate - or even more common, to talk to others about the inadequacies of a person or their work without ever talking directly to them[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- mistakes are seen as personal, i.e. they reflect badly on the person making them as opposed to being seen for what they are – mistakes[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- making a mistake is confused with being a mistake, doing wrong with being wrong[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- little time, energy, or money put into reflection or identifying lessons learned that can improve practice, in other words little or no learning from mistakes[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- tendency to identify what’s wrong; little ability to identify, name, and appreciate what’s right[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- often internally felt, in other words the perfectionist fails to appreciate her own good work, more often pointing out his faults or ‘failures,’ focusing on inadequacies and mistakes rather than learning from them; the person works with a harsh and constant inner critic

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

2. Sense of Urgency

- continued sense of urgency that makes it difficult to take time to be inclusive, encourage democratic and/or thoughtful decision-making, to think long-term, to consider consequences[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- frequently results in sacrificing potential allies for quick or highly visible results, for example sacrificing interests of communities of color in order to win victories for white people (seen as default or norm community)[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- reinforced by funding proposals which promise too much work for too little money and by funders who expect too much for too little[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Others are: defensiveness, quantity over quality, worship of the written word, only one right way, paternalism, "either/or" thinking, power hoarding, fear of open conflict, individualism, "I’m the only one", objectivity, and right to comfort.

Please read the entire article here.

As Tema points out,

“[Organizations] who unconsciously use these characteristics as their norms and standards make it difficult, if not impossible, to open the door to other cultural norms and standards. As a result, many of our organizations, while saying we want to be multi-cultural, really only allow other people and cultures to come in if they adapt or conform to already existing cultural norms. Being able to identify and name the cultural norms and standards you want is a first step to making room for a truly multi-cultural organization.” [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Please share experiences you have had or how your organization or network is working to dismantle racism and dominant culture.

The Promise of Co-Design

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]Co-Design Series Part 2[ap_spacing spacing_height="28px"]

THE WHY[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Co-design is a process that guides a group of people through various iterations of coming together to create something. This something might be a product, an activity, a project or a service. In fact, much of what is happening in networks is collaborative invention rather than traditional decision-making. Most decision-making in networks is done in collaborative projects as they are experimenting and creating something new. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Co-Design Is [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- POWERFUL. Co-design is a way of working together that assumes we all have something to contribute. The process distributes power to participants, utilizing each individual’s unique perspectives, expertise, and skills to create something new. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- COLLABORATIVE. Co-design employs processes that bring together many perspectives and capacity levels of participants. The processes are flexible, encourage collaboration, and incorporate reflection, and can change over time as the group’s goals change and adapt.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- TRANSFORMATIVE. Co-design and the culture change it requires can help us toward our bigger goals of social transformation, as we create new ways of engaging with each other and our own communities.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

THE WHAT[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

To get a deeper sense of what co-design is, here are three definitions:

The co-design approach enables a wide range of people to make a creative contribution in the formulation and solution of a problem. … Facilitators provide ways for people to engage with each other as well as providing ways to communicate, be creative, share insights and test out new ideas. John Chisholm -- Senior Research Associate, Design Management, Lancaster University.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Participatory Design (PD) refers to the activity of designers and people not trained in design working together in the design and development process. In the practice of PD, the people who are being served by design are no longer seen simply as users, consumers or customers. Instead, they are seen as the experts in understanding their own ways of living and working. Elizabeth B–N. Sanders

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Our definition: Co-design is a participatory, reflective, and adaptive process used to design and create. By centering participants as experts, it decentralizes decision-making and power, facilitating the transformative power of small groups.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="30px"]

THE HOW[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

When utilizing co-design as a process, we are guided by the following principles as distinguished from conventional design processes:

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Guiding Principles |

|

Conventional design |

Co-design |

Decision-making power |

|

| One person or a small group makes the majority of strategic decisions | Many people are engaged at many levels of a hierarchy (or across a network) in strategic decision-making |

Leadership and experts |

|

| A top-down, expert-led approach is utilized which offers limited opportunities for collaboration | Co-design honors participants as the true experts in their fields, creating many opportunities for collaboration throughout the design process |

Structure |

|

| Rigid structures (eg. a strategic plan) are used that lock the work and/or process in place after a decision is made | Co-design utilizes flexible formations that allow both the content of the work and the process to change over time |

Flexible engagement |

|

| Creates systems that maintain individuals at consistent levels of engagement with the work; individuals tend to be highly involved in design or not at all | Allows for individuals to participate at varying levels that may change over time; for example an individual may participate in the design group weekly, join monthly steering committee calls, or give feedback once in awhile |

Reflection, learning, and adaptation |

|

| Lacks reflection points or reflection is not used to inform growth and adaptation of the work | Reflection is a built-in, frequent process used to adapt strategies and priorities over the lifespan of the project |

Cultural shift |

|

| Promotes a dominant culture that disregards or actively excludes some voices and perspectives | Co-design opens us to new ways of working together by establishing a process that allows multiple individuals to take ownership and step into leadership roles |

Product versus process |

|

| Focuses on the end product and how individuals might interact with it | Co-design centers process (rather than end product) as a way to engage and continue engaging |

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

IN SUM[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Conventional design, decision-making, and creation processes focus power in one individual or a small group, creating a system that is less conducive to innovation and hinders emergence of new leaders.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

We believe the process of co-design shifts these power dynamics, empowering participants to have ownership over the process and product. Because of this, we believe co-design can help networks respond to emergence, become more innovative, and foster transformation at both the individual and network level.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Almost every aspect of network action, operations and governance can benefit by using co-design processes. For example, when people are self-organizing collaborative projects, they can co-design what they are doing. When a network is articulating its purpose, it can do so through a co-design process asking network participants to work in small groups to generate what they would like to see in the purpose statement. When networks are planning a convening, they can do like Leadership Learning Community (LLC) has done and invite anyone who wants to be part of virtual sessions to co-design the gathering.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

Inherent in co-design is the idea that all individuals have perspective, experience, and expertise to bring to the table. This means we’d also love to hear your perspective on co-design! Have you seen co-design techniques used in your network? How could you envision co-design supporting your small group?

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]

Read Part 1 of the Co-Design Series HERE

Three Ways To Foster Education On Complexity Using Network Visualizations

There should be more focus on systems thinking in education, Roland Kupers argues convincingly in the Global Search for Education on the Huffington Post. As complexity always involves interconnectedness between components, I find network visualization particularly useful in my educational practice.

- It creates systemic awareness, because users are forced to think about interrelationships: linear versus non-linear relations; coping with uncertainty; etc.

- It counterbalances the urge to automatically take the reductionistic approach to problems and issues. In other words: next to analysis –quite literally: taking apart to study the components- it makes room for synthesis –zooming out to the constellation on the system level.

- It provides a kickstart for introducing key concepts in a non-technical way.

- It fosters dialogue between students, pupils or stakeholders.

Here, I provide three ways I find promising to explore further.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]1. Promote Network Literacy in primary, secondary and tertiary education simultaneously

I am grateful to the NetSciEd-initiative for having coined the term Network Literacy, to promote the use of network science concepts in primary and secondary education. This could involve the creation of conceptual network visuals, drawn by hand. It could also entail creating more formal networks made with datasets and software.

I am convinced this is an excellent way to build on young people’s innate capacities of exploration, wonder, creativity and sense of interconnectedness.

However, I think it will take some effort to create leverage with teachers in our present day educational system. As Kupers points out, this system is characterized by high degrees of path dependency, with a firm basin of attraction in the reductionistic tradition. From my experience with education in the Netherlands, I agree with him. Therefore, I would also suggest promoting Network Literacy in tertiary educational curricula, to teach the teacher.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]2. Use network visualization to integrate Network Literacy with 21st Century Skills in curricula

I see 21st Century Skills like creativity, critical thinking and effective cooperation getting more and more popular in designing new educational curricula. Through my experiments with network visualizations I discovered that they can help both students and professionals to work on these skills.

I experimented with network visuals in professional education settings, e.g. with journalists and journalism students. This ‘Systemic journalism’ enabled them to create more angles and story ideas, fostered their willingness to share knowledge and enhanced a more future-oriented perspective.

Imagine a class of journalism students, each researching municipal financial policy in relation to construction projects.

In drawing network visuals of interconnected stakeholders, they applied creativity and critical thinking skills. In presenting and discussing their visuals, they tested basic network literacy skills as well as communication and problem solving skills.

Kupers asks, “How can a student pose a question in a physics class, based on an insight gained in a poetry class?”. Using some kind of network visualization could help creating a non-technical common complexity language.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]3. To enhance momentum, visualize the process of change in education itself

Kupers says, “the level of change required is both subtle and profound. In keeping with insights on how systems learn and change, it appears best to experiment widely, connecting and building on pockets of progress.”

Identifying key innovators, hubs and other players in the educational network, and visualizing their interconnectedness can have a profound impact on the pace of change.

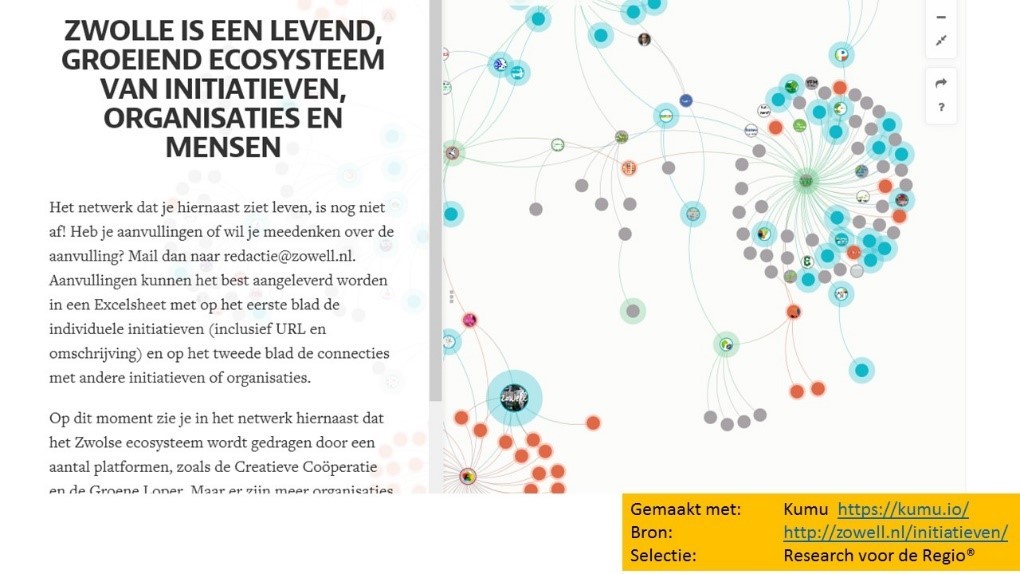

In a similar context, I helped setting up an interactive graphic depicting a ‘city ecosystem of social initiatives’. Using software from Kumu, an overall view looks like this:

Publishing a network visual like this not only helps spreading knowledge, but also triggers people to (inter)act.

Further exploring these three paths to me looks like a promising strategy.

"The task of knowing is to swim in the complex" -David Weinberger

Originally published May 16, 2016 on LinkedIn

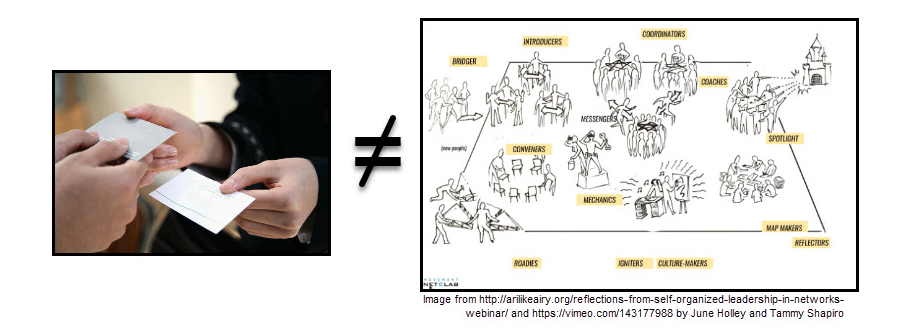

Network-ing Does Not Equal Network WEAVING

Those of us who work with change networks could sometimes do a better job of clarifying the distinction between 'networking' and 'network weaving'. Leaving that distinction un-articulated and merely implied inclines those who are new to the discussion to default their hearing to the generic-mainstream meaning of 'networking'. It leaves much of what is important and different about network weaving either un-said, un-heard, mis-understood, or suspect.

Now don't get me wrong - generic 'networking' is indisputably important. Contrasting something to it doesn't mean devaluing it.

And in reality, there's a world of overlap. Either can merge into becoming the other. You could personally be doing one, in the context of the other. And what you think you're looking at depends on where you fit in the network. There isn’t a bright line. My pretense at precise distinction is merely for the sake of nudging us a little further along the spectrum of what's possible.

Because - there's more power and potential in a social network than we've been taught & have grown accustomed to recognizing. And it's hard to access that 'more', if our words limit our imagination. So this is as much about what we're IMAGINING we're doing while we're doing it, as it is about precisely WHAT we're doing.

For those of us who don't resonate to Harvey McKay's 'Swim With the Sharks' and that ilk - the default, mainstream meaning of 'networking' can be a big turn-off . We've come to understand it as a specific, often self-serving, not-necessarily-authentic, social butterflying kind of activity. To many of us 'networking' is a popularity contest - best left to smarmy salesmen, politicians, corporate CEOs & lobbyists. We get a little queasy just contemplating joining those ranks. And no amount of rosy pep-talk convinces us. For introverts and those who value authenticity ‘Networking’ fires up the wrong imaginings.

But beyond being a potential turn-off, the common usage of the word falls short of the vision and purpose behind network weaving. 'Networking' tells the social butterflies they've arrived (an assessment the rest of us can’t agree with), while it leaves much of a network's deeper potential impact and generativity untapped.

We need different words to signal that we're leaving the default meaning behind and talking about something more. And we have them, we just need to use them.

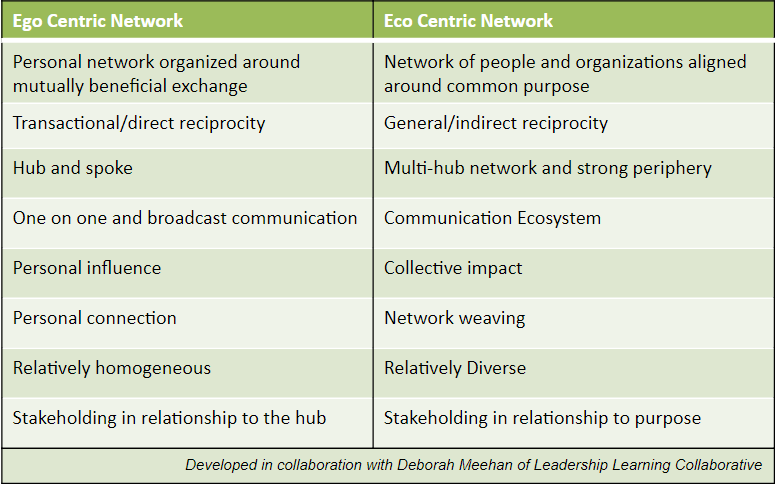

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]A DIFFERENCE RECOGNIZED BY SOCIAL NETWORK SCIENTISTS

Social network scientists have some technical terms that can help us explore this distinction. Terms for different ways of focusing on, or 'scoping' a network for analysis. They are 'ego-networks', 'socio-networks', 'open-networks', and 'eco-networks'.*

I'll say more about 'ego-networks' and 'eco-networks' in a moment, but for the curious, I'll just say this about the other two:

A 'socio-network' is a 'network in a box'. It has clearly-defined, solid boundaries - such as “everyone who works at Company X”, “or everyone who goes to School A” - it only looks at the relationships existing within that boundary - no-one else is relevant.

An 'open-network' is what it sounds like - there are no boundaries. The internet is an open network. Twitter is an open network, Facebook is an open network - anyone can open an account and anyone can be connected to anyone. There is no limit to who might be included in a network map of an open network. In theory, it includes the entire human race (or even further).

*From Understanding Social Networks: Theories, concepts and findings by Charles Kadushin

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]NETWORKING IS TO NETWORK WEAVING WHAT EGO-CENTRIC IS TO ECO-CENTRIC

For our discussion here, the more interesting technical terms are 'ego-network' and 'eco-network', which fit the distinction I'm trying to make almost perfectly. So let's dig in:

An Ego-Network revolves around a core person - it is defined by direct relationships to that central person and doesn't include indirect (2nd degree) relationships or persons unknown to the core person. Sounds a lot like what we get from 'networking', right? It's all about 'me'.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]What's an Ego-Network?

On a network map it looks like a hub with spokes. The relevant connections are to the single node at the center.

In our society, an ego network is generally connected around support of the core person in some way - important career contacts; the politicians a lobbyist cultivates; the network of family, friends and caregivers around someone with a severe illness, or something like the child support network I was gifted with as a young single mom, made up of sage advisors, friends who babysat regularly (or with whom I swapped regular babysitting) so I could work, friends who would drop everything to come get the kid if I had an emergency, and the kid's dad who gave me big chunks of time off. In that case, the connection to me (and the kid) was what was relevant - whether or not any of them knew one another didn't really matter. There was no larger purpose than helping me out or enjoying my kid.

This is the type of network that 'networking' tries to build and leverage. It is often based on direct reciprocity (I scratch your back, you scratch mine), is personally maintained (I work to maintain the relationship - stay in touch, send gifts, etc.), and often requires a direct match between my needs & yours - if there’s no direct match, there’s no relationship. (i.e. if you can’t help me raise my kid, I have far less reason to sustain our relationship, given my limited time and energy). And it's often homophilic ('like attracting to like') or relatively homogenous. My kid-network consisted entirely of older-moms, current-moms, wanna-be moms & one dad.

And because of their relative homogeneity, ego-Networks can easily become echo-chambers.

If the hub of an ego-network goes away the network falls apart. In an ego-network, the person is the purpose, and without that person, the connections are gone. My marriage (wonderful as it is), ended a lovely phase of networked connectedness in my life, because the purpose of our interactions (my need for help with child-raising) ended and the network drifted apart.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Eco-Networks Fit Between Socio-networks & Open Networks

An Eco-Network is a relative newcomer to the network-science labelling game. I don't even know where I got the term from. It's not in the book I pulled the others from, which is what I'd expected. I know I've come across it in a few places over the course of my network reading but haven't been able to re-find them - so if anyone reading this can find them, please share with us!

In any case, an eco-network sits somewhere between a socio-network and an open-network. A socio-network (the 'network in a box') generally has a centrally defined, narrow purpose (think 'mission statement' or 'avoiding organizational bankruptcy'); a clear & precise definition of inclusion (think 'everyone on our payroll' or 'the roll-call list'); a relatively centralized & hierarchical command system; and officially-sanctioned & controlled information and resource flows (balanced by secret, un-sanctioned information flows). Whereas an open network is unbounded, random, directionless and incoherent (think Twitter, FaceBook, Instagram).

So we could think of an eco-network as skirting the boundary between rigid pseudo-control and a free-for-all. In my mind, an eco-network is the social equivalent of that strange attractor within a system that generates ordered patterns out of chaos. To me, an eco-network has the potential to generate a collective path from our current world - a world presently oscillating between destructive authoritarian rigidity and chaotic collapse - to a new world, built on an evolved understanding of order/structure, connection, and thriving.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]What IS an Eco-Network?

But what does all that MEAN, practically speaking?

Well, it helps to think about ecosystems. For one thing, both eco-networks and ecosystems only thrive with ample diversity.

For another - in both cases, flows of resources (whether money, information, skills, trust and shared inspiration or nutrients, shared environmental context, water and sunshine) are complexly reciprocal, as opposed to transactional. In a forest ecosystem, no-one barters with the squirrel to get it to poop out worm & fungi food. And in exchange for the squirrel poop, worms & fungi don't break the elements down fine enough so that plant roots can absorb them because because the trees or the pooping animals pay them to - they do it because that's what they do, it's part of their organic process. The trees & other plants only grow if there are adequate nutrients and water - and when they do, they create food some of the animals need to survive (and poop out), some of which become food for other animals, and it all requires water, water retention, healthy soil - and so on. There is an organically-driven flow of value, based on adequate diversity, that is not directly transactional.

There is no need for direct transactions because each community member's survival depends on the in-flows (food, etc.) and out-flows (poop, etc.) of all the members. Transactions are too small a dynamic to support the complexity and adaptivity of an ecosystem.

The ecosystem forms an interdependent network of a huge variety of life forms, moving a broad range of nutrients freely through a complex system of flows that sustains the whole thing. Pull out too many parts, or just block up too many of the flows from one component to another and the whole thing collapses. And when I say ‘flows’ here, I mean ‘connection’/’relationship’. You could have all the pieces of the system/network, but if they weren’t able to interact, you wouldn’t have a network, let alone a living system.

In an ecosystem, there is also no 'boss', no centralized command & control. The whole thing works because of how the community fits together, not because someone designed it that way. A social eco-network is similar. There may be players with larger impacts and greater input into direction, but that doesn't mean they master-mind and control the whole thing.

Another thing a social eco-network and a ecosystem have in common is boundaries. They may be fuzzy, but they are real and discernable. For instance, there is diversity, but the diversity isn't infinite (like it could be in an open network) and it certainly isn't random. Whales don't occupy forests, butterflies don't do arctics, polar bears don't co-exist well within rainforests.

With ecosystems the boundary is environmental, the community members all thrive within a similar environment. With an eco-network, the boundary is purpose. And the boundary is what holds the community together.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]The Point of an Eco-Network

So - ultimately - the main distinction between an ego-network and an eco-network is this - the eco-network exists to support a purpose, not a person or an organization. It supports a broad purpose that is greater than any of the individuals involved, but which benefits all the individuals involved. It's also a purpose which can't be served nearly as effectively by individuals (or individual organizations) acting on their own, without the diverse & reciprocal flows of support and information that characterizes an ecosystem.

The glue, then, is not ONLY strong personal bonds (as in an ego-network) - tho it won't ever work without a lot of them - it is ALSO an intention that is larger than the personal bonds. It is an intention to be one part of a larger, purposeful, whole. An intention to help develop that whole and the individuals within it in ways that are generative for oneself as well as for the larger purpose.

An eco-network, then, has: a purpose; diverse membership; complex reciprocity; multiple 'centers' with multiple roles; and a robust and free flow of information, resources, capacity and care to where they are needed most. A flow that both includes and transcends the bonds of personal connection, and that emerge from the interactions.

Far from being a popularity contest, an eco-network is a puzzle we can do together. It’s a fun but serious game of learning about fits and flows - about how to amplify the impact of what each member has to offer. It’s a dance between the individual and the collective, an ever-shifting experiment with order emerging from chaos.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]But So What?

Why do I think any of this matters?

I believe it matters because our imaginations matter. All of our actions and behaviors are driven by and reflect our deepest beliefs and values - and these are all gestated in the womb of our imaginations. What we can't imagine, we can't create. And the only way we ever create something new, for which there is no current model, is if we imagine it first. I believe it matters that we pull our imaginations a step past what we already know, do & envision - into a higher level of generative capacity - in a way that affirms and includes everyone, not just the social butterflies.

And I believe that if we tease out a clearer understanding of the values and intent of network weaving, if we tempt our imaginations into this fresh, promising new territory, we go further to affirm and generate the kind of world we want to live in together. We affirm that weaving an impactful and resilient change network:

Is not a contest - it's more about discerning the right network for ourselves (so we don't end up like a polar bear in a rainforest), finding our natural place, supporting the flow of nutrients where they need to go, expressing our unique contribution & helping others do all of that as well.

Means supporting others, whether they're able to support us or not, serves the overall purpose we’re all trying to promote.

Requires a lot of different roles, as well as understanding and appreciating the roles that are different from our own.

Means going beyond developing our own personal relationships, and helping others develop relationships that enhance maximum flow of value throughout the network.

Requires recognizing and acting on the recognition that there is a limit to how much can be accomplished in a transactional context, and that system change is built on an abundance of relationships across differences.

Stimulating this kind of understanding & imagination requires many tools & approaches - Mapping is the tool Tim & I personally contribute to the puzzle. Powerful, adaptive eco-networks are the shift we're trying to support.

What contributions are you interested in making & to which greater purpose? Please join the conversation in the comments section below.

Originally published March 26, 2018 at GreaterThanTheSum.com

Building Communities Through Network Weaving

In 2004, Valdis Krebs and I collaborated on an article that described the stages of network development and introduced the term network weaver.

In 2005 an edited version of this paper was included in the Nonprofit Quarterly.

This article is newly added to our RESOURCES page... and it's FREE!

To download CLICK HERE

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Foodshed team learns how to establish consent instead of consensus

In Propositions for Organizing with Complexity: Learnings from the Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP), Nikki D’Adamo-Damery described nine propositions that emerged from the work of the AFP. Proposition #2 was: “Establish Consent instead of Consensus.” The following story describes one of the experiences we had together, when Tracy was facilitating the management team, that led to this proposition.

This story begins when the AFP management team was making decisions about how they were going to award mini-grants to on-the-ground projects that addressed community food security. The team included the principal investigators, graduate students, extension agents, and representatives from community-based organizations, and so reflected some of the diversity of the system within which they were working. The team was using a collaborative decision-making framework, and the basis for decisions was the principle of consent.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

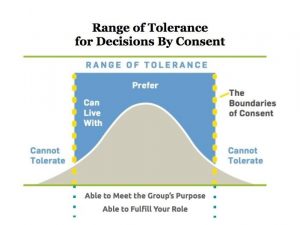

The principle of consent

People often think there are only two choices for how we make governance decisions: by majority or consensus. Most people fail to realize that decision-makers have a third option – decision-making by consent – that can be preferable to either of these for governance decisions. The Consent Principle means that a decision has been made when no member of the group has a significant objection to it, or when no one can identify a risk the group cannot afford to take. In other words, the proposal is not out of their Range of Tolerance (see below). Those risks are things that would undermine the purpose, or that would create conditions that would make it very difficult for a member to perform his or her role.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

The test for the management team

The urgency to get the funds out into the field put pressure on the team to make a decision. On the one hand, there was clear value in having these different perspectives at the table as they discussed funding priorities and how to make the application process more accessible. On the other hand, there were conflicting opinions when it came to designing the application. Was it ethical for representatives from community agencies who might apply for the grant funds, to design the actual application? A professor said “no” and a community agency rep said “yes.” There were concerns that the difference of opinion might limit progress.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Consent is grounded in dialogue, not debate

It was through this experience that they learned that, by using consent as the basis for decisions, the team did not have to agree. Instead of debating, they inquired into what was out of the range of tolerance for each of them. They listened to each other’s objections as feedback about potential risks so they could adjust the solution to mitigate those deemed unacceptable.

Here’s what they discovered:

- The professor was actually concerned that there might be a perception about a conflict of interest if the community partners applying for awards were involved in the design of the application questions. That perception was the risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the project’s credibility and trust in the community.

- The non-profit director was concerned about the integrity of inviting community reps into the decision-making process, and then withholding that power when issues got sticky. That power dynamic was a risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the trust within the core team.

Once they discerned the reasons for concern – and chose to respect what was important to each of them – they found a way forward. The decision was to include the community partners in decisions about the application design, as full decision-makers, AND to be fully transparent in all public communications about their participation. As a side note, they were simultaneously clear that, if one of those community-based organizations applied for a grant, they would recuse themselves in the selection of grant recipients.

The grant application design and process went mostly smoothly with no conflict of interest issues. The second round of distribution of mini-grants moved even more quickly, building on the trust that had been built the first time around.

This blog post originally ran on the Virginia Cooperative Extension: Community, Local, and Regional Food Systems blog. and at CircleForward.us

*The Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP) originated in 2011 as a grant funded through the USDA’s Agriculture, Food and Research Initiative (AFRI) grants program (Award Number: 2011-68004-30079). Virginia Tech served as the lead academic institution in partnership with North Carolina State University and West Virginia University for a five-year endeavor to address community food security in western North Carolina, southwest Virginia, and West Virginia.

By Tracy Kunkler, MS – Social Work, professional facilitator, planning consultant, and principal at http://www.circleforward.us/[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Please post any thoughts, comments or stories in the comments section below.