Understanding Movements

What follows is an excerpt from the Understanding Movements report, researched by Kapil Dawda, commissioned by Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies. You can access the full report and the accompanying Understanding Movements deck at the bottom of this post.

A movement in its simplest form is an act or process of moving. For example, an object moving from point A to point B embodies a movement.

In the context of social change, there are multiple ways to move from point A to point B. The most commonly encountered approach in the modern world is a programmatic one. It is employed by social and private sector organisations and governments through scale programs, like the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan. There are also collective-impact-based approaches, which have a more distributed and networked way of approaching change. Lastly, there are movements, a particular kind of collective impact.

In the context of social change, a movement has:

- A diverse collective of people and organisations coming together as participants

- The shared intention to create wide-scale, transformational change focused on a social, economic, environmental, or political problem that guides the collective direction

- Distributed, shared and bottom-up action by multiple participants, including those at the grassroots

Many famous movements emerged in the face of pressing crises. Some examples are the

Quit India Movement or Civil Rights Movement of the past and contemporary movements like the Arab Spring or #MeToo. However, movements are not limited to those that arise in response to a crisis that escalates through triggering incidents. Many others address latent, not urgent problems by applying the same principles. For example, Service Space is a global movement to unleash the innate spirit of generosity in people. YouthXYouth is another example of a worldwide movement focused on bringing back the agency of young people in their learning experience!

Movements are more than collective, confrontational action against oppressors in power. This view over-simplifies the complexity and leads us to think in terms of just bilateral dynamics. Many lasting movements take a more systemic view. To view movements more holistically, we must observe the relationships between the leaders, the participants, the organisations and the stakeholder groups involved. It is also worth examining who the leaders are, what they do, how they lead and most importantly, why they do it. It enables us to appreciate how movements work with a diverse collective to bring social, environmental or political change.

In their book New Power, Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms define New Power as “a current. It is made by many. It is open, participatory, and peer-driven. It uploads, and it distributes. Like water or electricity, it is most forceful when it surges. The goal of ‘new power’ is not to hoard but to channel.” By this definition, movements are a form of new power focused on bringing societal change.

Access the Understanding Movements Report and Presentation Deck HERE at NetworkWeaver and HERE at Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

This resource explores:

- What are movements?

- What is their relevance in social change?

- What are some of their defining features?

- How do they differ from programs or collective impact?

Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies (RNP) supports ideas, individuals and institutions doing ground-breaking work that enables a strong samaaj (society). The areas of work constitute a wide range spanning Access to Justice to Water. RNP has identified Active Citizenship, Climate and Biodiversity and Young Men and Boys as priorities.

Kapil Dawda is the Co-Initiator of the Wellbeing Movement, a Team Member at Viridus Social Impact Solutions and an active member of the Weaving Lab and Presencing communities. He is keen on tapping into the power of many to enable everyone, especially youth and children, to lead thriving lives

Originally published at Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

by Kapil Dawda, commissioned by Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

Being a strange attractor

This article forms the first in an intended series of articles. The main theme of that series is to reflect on a new language for social transformation. For me, language goes beyond words, concepts or metaphors. Essentially, it is the filter through which we look on life, perceive our environment and plan our actions. Changing our language, therefore, is a powerful way towards personal and collective transformation.

Every article of the series is dedicated to a specific theme or concept. Yet, rather than enriching your vocabulary, it is much more the shift in perspective underneath the concept that I want to contribute to. In our case, strange attractors are a concept from chaos theory. Exploring strange attractors are therefore a gateway into the world of chaos, dynamical systems and complexity. And what is a strange attractor?

Well… there is no simple answer. But I have an idea where to start.

To enable non-linear reading I visualised the article on kumu as a dynamical map:

The starting point

Life puzzles me. Partly my own. Even more so fundamental questions like how life emerged? Or human sense-making: how on earth is it even possible that we can communicate? I jot down these black & white symbols on a keyboard, they appear on a screen and you can understand what I am trying to say.

In a similar way: given the goodness and well-intendedness of many of us, how are we able to create phenomena like environmental destruction? What social and psychological principles are at play in our daily lives that enable outcomes we don’t want?

The reasons for asking myself these questions are twofold: I have a genuine curiosity to go to the bottom of things, wanting to understand the root causes rather than superficial appearances. Understanding for its own sake so to speak.

And then there is this undeniable desire to drive social change. I came here for a reason. Not to accept what is happening around me, but to play an active role in co-creating our future. This part of me is highly intentional, using knowledge to identify leverage points for personal and social transformation. More specifically, I am eager to learn and embody how I can contribute to meaningful change.

In the past years, those motivations (or better: driving forces) lead me down some rabbit holes, both in theory and practice.

Embarking on a journey into strange lands

Due to my fascination for social change, it is not such a surprise that I studied sociology. There, most approaches and (meta) theories are relatively systematic, with the ambition to explain and the tendency to categorise. It is difficult to speak about the diverse field of sociology in general terms. Yet what I often found was theories and methods that made sense of events once they happened. Categorising the past and projecting it into the future. And then making those events fit the theory. It reminded me of the story of the little prince, visiting the king on his planet*:

Little prince: “Sire–over what do you rule?”

King: “Over everything,” said the king, with magnificent simplicity.

[…] Little prince: “And the stars obey you?”

King: “Certainly they do,” the king said. “They obey instantly. I do not permit insubordination.”

Little prince: “I should like to see a sunset … Do me that kindness … Order the sun to set…”

King: “You shall have your sunset. I shall command it. But, according to my science of government, I shall wait until conditions are favorable.”

Little prince: “When will that be?” inquired the little prince.

King: “Hum! Hum!” replied the king; and before saying anything else he consulted a bulky almanac. “Hum! Hum! That will be about– about– that will be this evening about twenty minutes to eight. And you will see how well I am obeyed.”

I was curious to find out if there is more. My backpack filled with Weber & Elias, Luhmann & Habermas, Foucault & Bourdieu, Berger & Luckmann I expanded my search for answers; and wandered off into the strange lands of complexity science, chaos theory and fractal geometry. For me, those excursions have not only been fascinating from an academic perspective, but also insightful for my life as a social entrepreneur. I invite you to come with me and discover those strange lands. And I promise that I will guide you back at the end.

What’s the weather like over there?

Welcome in the world of complexity! As with most other foreign places, things work a bit differently here. Let’s start with a quick introduction first: As James Gleick in his groundbreaking book “Chaos. Making a new Science” put it:

“the act of playing the game has a way of changing the rules”

If you want it or not: as soon as we arrive at the shores, we are not merely passive visitors. We are active agents and influence what is happening here. A complex system, therefore, is dynamic and adaptable. It responds to its environment yet has its own “agenda”. The question, then, is what provides orientation for the behaviour of the system and the actors within it? The answer: Strange attractors!

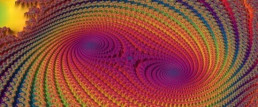

Some of us may be familiar with pictures like those:

CC BY-SA 3.0.

It shows the so-called Lorenz attractor. It describes visually how a dynamical system behaves, in this particular case the flow of fluid under certain conditions. The attractor itself is “the whole thing”, the space that spans all potential behaviour. We can see that there are two central attractor points around which the system seems to rotate. The strange thing is that – despite having knowledge about all relevant parameters – it is impossible to predict how the system will evolve over time. This is called nonlinearity. Caused by those weirdly arranged attractors.

As an analogy, you can imagine the weather: Weather with all its components (temperature, air pressure, humidity etc.) is the system. If we measure those components and visualise them, we get our (visualised) attractor of the system; most likely indicating us certain central points. In most geographical locations, there are two main states, summer (dry season) or winter (rainy season). Let’s say “summer” is the attractor state on the left, “winter” on the right. Any day of the year constitutes a point. Usually, we know if it’s summer or winter, and how the next days will roughly be like. Yet any precise prediction beyond 10 days is almost impossible. And at some point, the system will shift. We know it will happen, yet we don’t know the exact day. No matter how much information we have at hand.

As our nerdy friends would say: The weather is a chaotical & nonlinear system. Its behaviour rotates around two central attractor states. This leads to the fact that the system is locally unstable yet globally stable. That’s quite strange, yes. But what does that have to do with social transformation?

To me it seems that societies, communities, families (put any social system you like here) rotate around certain states as well. Conservative or liberal, open or closed to “outsiders”, free markets or state-centred economies. Those systems experience periods of prolonged stability (economic growth with prosperity), followed by a rapid & sometimes unexplainable “switch” (the dotcom or housing bubble bursting). Looking with that lens on my environment has helped me a lot to understand social change. Order and chaos should not be seen

“as antagonistic and fixed states but rather as stages in a process of dynamic and transformational becoming”.

― Elisabeth Garnsey and James McGlade

The same accounts for any dynamical system with more than one equilibrium, more than one attractor state so to speak.

The dance between polarities

Butterflies have two wings. We have winter and summer (or rainy and dry season). There is life and there is death. Following those examples, polarities seem to unite stability and movement. In that sense, opposites are not really opposing each other. They create space for life to happen in between.

“The only way to make sense out of change is to plunge into it, move with it, and join the dance.”

― Alan Watts

We tend to care about what happens around us; and oftentimes have the desire to influence it in a certain way or direction. Joining in the dance does not mean to accept everything that happens. Rather, it means to understand that it is the underlying rhythm that moves us. To change the dance, we have to change the music (or the polarities in our case).

Taking the principle of nonlinearity into account, there are ways to make a certain behaviour (of a system) more likely, orientating it towards a (desired) attractor state. Yet, despite our best efforts, we can never know what will actually happen. Life is unpredictable. But life is not random either.

And we have a true super-power on our side. Social systems differ from the weather in one important aspect: the attractor states are social constructions. They are based on language and culture, on individual and collective agency. And what was constructed once by people can be changed. In other words: We have the capacity to create and establish new attractors.

The attractors of our time

“Grown-ups love figures… When you tell them you’ve made a new friend they never ask you any questions about essential matters. They never say to you “What does his voice sound like? What games does he love best? Does he collect butterflies? ” Instead they demand “How old is he? How much does he weigh? How much money does his father make? ” Only from these figures do they think they have learned anything about him.”

― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Translated into a social context, we can see an attractor state as a shared set of beliefs and internalised symbols and habits. A fix point within a certain system like family or economy. The word “purpose” comes relatively close to it. Let’s examine what the current attractor states of our society are. For the sake of length and digestibility, we will keep it short, unscientific and subjective.

Western thought is highly influenced by the idea of a mechanical universe (Newton) and mind (Freud). It emphasises the difference between an individual and its environment, and the differences between people. The centre of this worldview, then, is the autonomous and isolated individual.

“I, a stranger and afraid

In a world I never made.”

― A.E. Housman, Last Poems

As we know, attractors stabilise behaviour. The attractors emerging out of this particular worldview are economic growth & meritocracy as well as the attempt to control our environment (which includes both our natural and social environment). It is a paradigm of competition, of “me/us against”. As a consequence, we usually only focus on one side of the polarity; the side that we prefer and desire. And we pathologize the other side. Economic growth is good, de-growth is bad. Being happy is desired, depression is something we have to treat with medication. It’s like wanting to breath in all the time, judging all the outbreaths.

Still, orienting our behaviour towards those states brought enormous prosperity (for some) and stability. We live in an era of unseen peace, economic wealth, scientific discovery and global interconnectedness. Yet something is off. It feels like our own inner attractors (our personal purpose, our desire for integration and wellbeing) pull us away from society’s inner attractors. The tricky thing is that both types of attractors – individual and collective – are usually invisible. Usually.

“And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

From opposition to integration

We are still in the land of complexity, remember? We learned that here, attractors of a system are not seen as opposites. On summer follows winter, follows summer, follows winter. The system is healthy when it shifts between both states. This leaves us with the question:

What are healthy polarities for us as society?

Let’s look at an example that some of us (me for sure) struggle with: balancing working and resting / free time. An alternative way to phrase it could be: Creating something specific (for others) vs. taking care of yourself only. The current paradigm likes to phrase that as “work-life balance”, one of the most horrible terms I know. As if working would not be part of my life. The underlying polarity is “being productive vs. allowing yourself time to be unproductive”. In a more mechanistic view to drive the point home: running the machine vs. oiling the machine. (with the addition that even “unproductive” time is often turned into a product – like consuming advertisement).

That’s not a healthy attractor to me. And I see myself falling into this polarity if I am not careful and attentive. An alternative way of phrasing it would be: I am enjoying my time either creating something meaningful for other people (a.k.a. working) or I enjoy to just do things for their own sake. In this way, the mechanistic attractor (work vs. life) is replaced by a more wholesome attractor (meaningful and intentional action & enjoying things simply for themselves). It’s still two polarities, yet they don’t oppose each other.

In a similar fashion, we can look at our climate crisis. We live on the expense of our environment. And this challenge cannot be solved with simplistic regulations or public claims that keep the idea of economic growth alive. No, the paradigm of economic growth is not compatible with environmental survival. It does not work to simply include nature into this growth-logic (calling it sth. like green technology). We need new polarities, new attractor states to address this challenge. An economic attractor that allows certain elements to be outside of the linear growth logic. What this could be I leave up for your imagination.

Sounds idealistic? Well, I would call it pragmatic imagination. As all we see around us was an image in our heads first, then turned into “reality”. One invitation I see here is to move away from a paradigm of needing to know and control, rather framing the attractor around a central question. How can we integrate work and free-time into a fulfilling life? How can we assure both our material wellbeing and the wellbeing of the nature that surrounds us? It’s OK to not have the answers (attractor states) yet. But we can (re)frame the attractor around them.

In this, the world desperately needs individuals who are capable of transcending the worldview of opposites, black and white, gain and loss, good and bad. A world of scarcity and competition. Not just conceptually, but with our actual behaviour and actions.

“We but mirror the world. All the tendencies present in the outer world are to be found in the world of our body. If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. We need not wait to see what others do.”

― Mahatma Gandhi

Strange attractors of this world, unite!

Are you seeking to create a future for yourself and others that is different from the present? As an activist, social entrepreneur, philanthropist, parent, consumer …? Then I would consider you as a change agent, or strange attractor. Somebody who inspires and motivates themselves and others to act on a worthy ideal. A strange attractor in that sense can be any individual, but also an idea, a startup or a movement we represent.

We may be far out in the old paradigm, and it is frustrating from time to time. But we can constitute the centre points in the new paradigm. We are the ones to create new attractor states for our common future.

So how can we do that?

I see two crucial steps to make this happen. And you may have guessed already: Number one is to be the strange attractor yourself. Be the space and inspiration for others. Embody a new path for action. Number two is to team up and create (new) social systems jointly. Both steps are courageous and bold. And here is why:

Embodiment is not only an intellectual exercise. Here I speak out of tough personal experience: Stating that I want to achieve something (e.g. to be a humble and inspiring leader) often created distance. Rather than motivating me, it made me (subconsciously) believe that I am not there yet. Doing the inner work is required. Knowing and accepting ourselves. Embracing our inner beauty, shadows and power. And there are no quick fixes or shortcuts.

Teaming up is even more delicate. It requires us to find each other, create thriving teams, organisations and networks. In short: institutionalise new attractors. Probably this will cause opposition. From others and from within. As it requires us to let go of our individual dreams to form collective ones.

My answer to that is: yes, that’s quite a task, but what else should we do? What else are we here for?

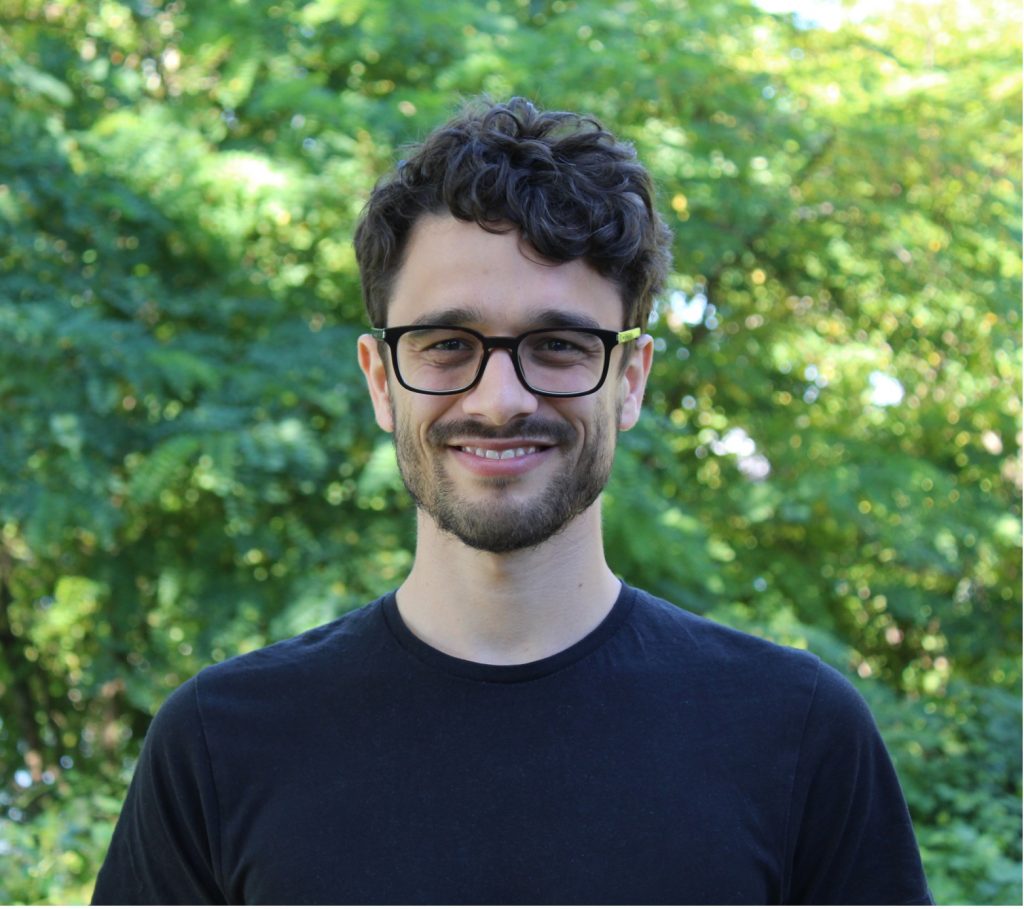

Jannik Kaiser is co-founder of Unity Effect, where he is leading the area of Systemic Impact. His desire to co-create systemic social change led him down the rabbit holes of complexity science, human sense-making (e.g. phenomenology), asking big questions (just ask “why” often enough…) and personal healing. Having worked in the NGO sector, academia and now social entrepreneurship

Originally published at UnityEffect.net

Energy Network Literacy: On Care-full Dis-Connection, Dis-Entanglement and Regenerative Flow Management

“i think of movements as intentional worlds, or perhaps more accurately as worlds designed by and for intentional people, those who are able to feel the world not as an unfolding accident of random occurrences, but rather as a massive weaving of intention. you can be tossed about, you can follow someone else’s pattern, or you can intentionally begin to weave and shape existence. and yes, the makeup of your web is the same matter as all that already exists, but your direction and pattern can be new, unexpected, agitating new growth. what results from your efforts depends on your intention.”

– adrienne maree brown

I recently returned from a week-long vacation with family to the so-called Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, and a particular location that is deeply nourishing and meaningful for its landscape, its link to family history on my wife’s side and (perhaps for these times) an unusual sense of community. I count myself privileged to have had the time and the opportunity to be in that place with those loving people, with that sense of multi-generational connection.

Heading back “home,” I could feel the tension mounting as my wife and I talked about re-entry. Before thought, my body tightened in anticipation of the return to the mundane daily tasks, to-do lists and un-answered emails/phone messages. The morning after our return, I somewhat absent-mindedly dipped toes into social media and felt my blood pressure rise. “What am I doing?” I wondered, even as I continued to wade in, pulled by questions about what happened while we were away and what new opportunities might be presenting themselves – FOMO (“fear of missing out”) in full effect. When I closed the laptop, perhaps 30 minutes later, I was aware of my stiff neck, shallow breathing, hunched shoulders, and whirling brain. Saved by a 12 year old daughter almost yelling, “Dad, c’mon, let’s get outside and play ball!”

As much of a proponent as I am of collaboration and networks, I am struck by how I can get a bit caught in the approach/avoid loop of connection, and mired in questions of “How to connect?” and “How much is enough connection?” and “What kinds of connection do I really need?” As I engage with others, I realize that these are pretty fundamental ponderings for navigating a more viscerally entangled world.

“When our ancestors spoke about a web of life, they were describing what Western science calls quantum entanglement. They understood that we all originated from the same seed of life, and when that seed exploded and carried life across our universe, we remained connected. Quantum entanglement tells us that any matter once connected physically can never be disconnected energetically (or spiritually).”

– Sherri Mitchell (Weh’na Ha’mu’ Kwasset, “She Who Brings Light)

More and more is being written, spoken and (re)-presented about the fundamentally interconnected nature of our lives, and of Life writ large. In a beautiful essay in Emergence Magazine (“When You Meet the Monster, Anoint Its Feet”) , which weaves connections between climate change, race, racism, evolutionary biology, ecology, myth and narrative, Bayo Akomolafe offers …

“Perhaps most important about this time is that the image of the human is being composted—or, we are experiencing great difficulty determining where the nonhuman stops and the human begins. Everything touches everything else in the Anthropocene—an observation that is supported by, say, current thinking about ‘holobionts,’ assemblages of bodies within bodies within bodies, or intersecting communities that toss out notions of separable individuality. We are holobionts. We live and are lived through; we are composite beings, companion species, emerging within and among assemblages.”

And, as Akomolafe later shares from his indigenous and experiential knowledge, bodies and beings transcend time. More recent research into intergenerational trauma (see the work of Resmaa Menakam and Thomas Hubl) shows that our bodies indeed know the score, not only of our own individual pain, but the suffering passed through our ancestral lines. Husband and wife, and astrophysicist and physician, team Karel and Iris Schriyver, in their book “Living With the Stars,” add that our bodies are always in dynamic exchange with … the wider universe! Our cells die and are replaced by new ones, renewing our entire biological makeup, using food and water as both fuel and construction material. This rebuilding happens by using elements captured in our surroundings and cycled through geological processes, all extensions of galactic explosions and ripples and atoms that formed through collisions with our planet’s atmosphere eons ago.

We are entangled in a multiplicity of ways, containing and residing within multi-dimensional multi-scalar multitudes. I find this simultaneously liberating, dizzying, humbling and dumbfounding. Knowing that everything is interconnected can inspire a profound sense of belonging and ease, yes, and sometimes it can make it a bit hard for me to plan or get through the day!

And so here we are, exquisitely entwined, and yet also individuals, or at least bounded organisms with a sense of individuality, of distinction, of the need to preserve the integrity and dignity of something called “me” or “self.” And the question of these times would appear to be how we can honor a healthy sense of self/individual, whole communities, and Life, all at once.

“To allow oneself to be carried away by a multitude of conflicting concerns, to surrender to too many demands, to commit oneself to too many projects, to want to help everyone in everything, is to succumb to violence. The frenzy of our activity neutralizes our work for peace. It destroys our own inner capacity for peace. It destroys the fruitfulness of our own work, because it kills the root of inner wisdom which makes work fruitful.”

– Thomas Merton

While there have been understandable and important pushes to get beyond the individualistic and atomistic view, I have the feeling that some of this emphasis, as with all pendulum swings, can go a bit too far. Seeing the world as profoundly interconnected might drive a strong desire to reclaim a kind of forgotten birthright, and in my experience, it can also result in getting lost, especially if it is guided by an underlying desire to fully understand, grasp and/or control it all (colonial mindset?). Or if that drive is purely to belong to something, anything, no matter its underlying values, to spare the pain of felt/perceived separation.

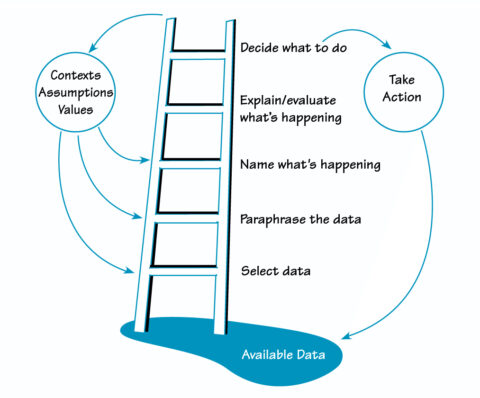

A certain view in contemporary physics holds that the world, the universe, is entirely made up of an infinite amount of information, a vast expanse of sensory inputs that all taken together would be utterly overwhelming to our individual apparatus. And so we have our human senses as filters to sift through, make sense and identify/assemble what is most … useful, interesting, advantageous. The point is, there is always more than meets (or at least is taken in by) our eyes, ears, nose, tastebuds, touch, etc. This calls to mind the ladder of inference, a framework we teach at IISC that helps people remember that we are often recycling conclusions we have drawn from a very partial understanding of reality, and that it might behoove us to expand our “view” to reach more helpful (just, prosocial, sustainable) conclusions and actions.

That said, simply taking in more, or making more connections, may not lead to a better place, if it results in overwhelming nervous systems. So it seems there is a balancing act here. Just as we often can’t do something new without letting go of something old, there is a need to modulate what one takes in – news, ideas, people, and possibilities. Connection and flow management. Energetic discernment. Intentional dis-connection and dis-entanglement.

What might this look like in this networks upon networks networked world? A few thoughts …

“Between you and me, now there is a line. No other line feels more certain than that one. Sometimes it seems not a line but a canyon, a yawning empty space, across which I cannot reach.

“Yet you keep reappearing in my awareness. Even when you are far away, something of you surfaces constantly in my wandering thoughts. When you are nearby, I feel your presence, I sense your mood. Even when I try not to. Especially when I try not to. . . .”

– Donella Meadows

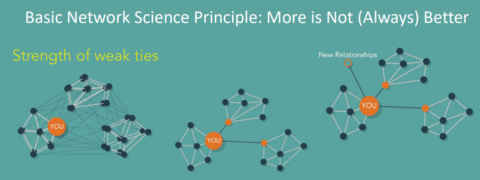

In a previous post, I shared some of the wisdom of network science as taught by Danielle Varda and colleagues at Visible Networks Lab. They make the point that when it comes to creating strong (resilient and regenerative) networks, more can be less in terms of the connections a person has. Connectivity and related flows can be ruled by a relentless growth imperative(capitalism?)that is not strategic or sustainable. More connections require more energy to manage, meaning there may ultimately be fewer substantive ties if one is spread too thin. Instead, the invitation is to think about how to mindfully maintain a certain number of manageable and enriching strong and weak ties, and think in terms of “structural holes.” For more on this social network science view, visit this VNL blog post “We want to let you in on a network science secret – better networking is less networking.”

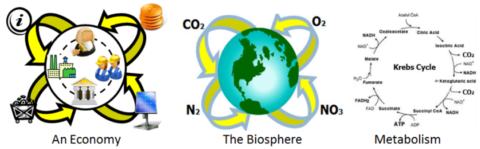

Over the last several years, I have been playing with a set of about a dozen principles (give or take) for network thinking and action. One that seems quite helpful here is the saying, “Do what you do best and connect to the rest.” As ecosystems become more robust and complex, individual participants are invited to carve out more specific niches, and be oriented towards synergistic and supportive relationships with others. In other words – stop trying to do it all, or connect to it all! It’s not possible, it can create unnecessary competition, overwhelm and inhibit “collaborative efficiencies.” This also aligns with a metric of energy network and systems science (see below), which focuses on the importance of a diversity of roles in healthy living systems. Share and spread the wealth!

As just alluded to, the emerging field of “energy systems science” points to a number of different factors or indicators that contribute to long-term living system (including human systems) health and thriving. Four of these indicators fall under the heading of “measures of flow.” Thinking about how these apply to our own and/or collective in-take and sharing of information/energy might be helpful for knowing what is “sufficient:”

- Robust cross-scale circulation: How rapidly (too fast?/too slow?) and well do a variety of resources reach all parts of an individual/social body?

- Regenerative return flows: To what extent does the individual/social body recycle resources into building and maintaining its internal capacities? Is there too little (depletion)? Is there excess (hoarding)?

- Reliable inputs: How much risk and uncertainty is there for critical (health promoting) resources upon which the individual/social body depends?

- Healthy outflows: What impacts do the individual/social body’s outflows have externally?

On a more personal tip, I have been married for almost 20 years. What has perhaps been one marriage from the outsider’s perspective has been many from the inside, as other long-standing intimate partners can surely appreciate. We have learned and grown over the years. One important lesson has been knowing when we are too enmeshed and need to separate for some time. There is a point of diminishing returns in many of our heated discussions/ arguments, and if we do not dis-entangle or dis-connect, we have learned, we can do damage to the relationship.

Along the same lines, two of our daughters are identical twins, now twelve-years old. What we have observed about them is what we have heard about many twins – they are truly uniquely connected. There are many times when we quietly watch with fascination as they, seated on opposite ends of the room, engage in similar gestures (scratching their heads with the same hand at the same time, for example) seemingly without direct awareness. Quantum entanglement in full effect! And they can get themselves enmeshed at times and in ways that drive each of them, and the entire family system, to the edge. They are learning that they need and how to differentiate and take space, even as they have a natural gravitational pull to their other half.

Knowing when to create a bit of a boundary (what Buckminster Fuller once called, “a useful bit of fiction”), a separate amniotic sack if you will, and when it is optimal to connect more fully often requires attention and discernment, for all kinds of relationships.

“Beware of the stories you read or tell; subtly, at night, beneath the waters of consciousness, they are altering your world.”

– Ben Okri

The movie The Social Dilemma and the work of Douglas Ruskhoff (see Team Human) both point to the perils of getting caught up in our increasingly socially mediatized world. The algorithms behind these powerful tools are designed to capture our attention, pressing our buttons oriented towards hedonism (“likes”) and fear/outrage. A recent article in The Atlantic Monthly (“You Really Need to Quit Twitter”) points to how difficult it can be to break this habit. This is not to say that these tools are inherently bad or evil. They are certainly formidable, and require considerable attention and intention. Social media fasts and limited dips can help, as well as being mindful about what and why we are both sharing and consuming (see this other recent post for some considerations on this – The Wisdom of W.A.I.T.ing: Mindful Sharing in a Network Age.

If dis-engagement is not an option or ideal, there are a number of practices I have been learning and using that can help to manage energy exchanges, both in-person and virtual:

- From the Rockwood Leadership Program, I learned the practice of imagining that my body is like meshwork (think a fishing net), when something intense is coming at me, so that it can pass through me, and I don’t use too much energy resisting or having it get stuck in my body/psyche.

- From a couple of local trauma therapist who focuses on racialized trauma, I have learned the practice of using imaginative “shields” (in my mind’s eye) on the outside and inside of my body, to allow for energy coming in or going out. Silver shields on the exterior repel unwanted energy, and on the inside they keep precious energy in. Grey shields allow some energy in or out.

- From a number of practitioners, I have learned the practice of slowing my breath to manage energy flow, in-take and circulation.

- From Qigong Master Robert Peng I have learned how to use a “circuit breaker” for the life force (or “chi”) moving through me by enclosing my thumbs with the fingers on each hand, which can diminish intense energy flows when engaged with others.

- From The Weston Network/Respectful Confrontation community, I have learned the practice of being aware of my own personal space, surrounding my body, and respecting that boundary when engaged with others.

- Also from The Weston Network, I have learned about the practice of embodied energetic balance when reaching out to make contact with others, while not over-extending, and also maintaining a firm sense of grounding and dynamic flexibility. I have also been reminded, helpfully, that balance is never static. We are constantly in motion, if we are alive, and when “most balanced,” are actually able to recover quickly from being extended or engaged in some way. So a question to carry is “What supports my ongoing ability to recover?”

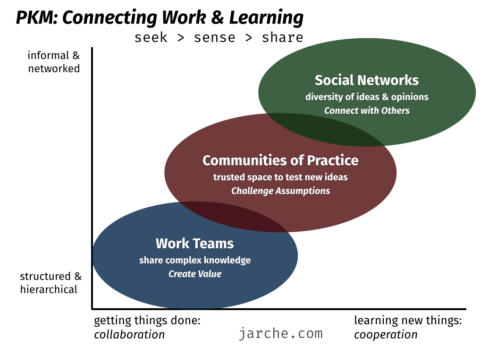

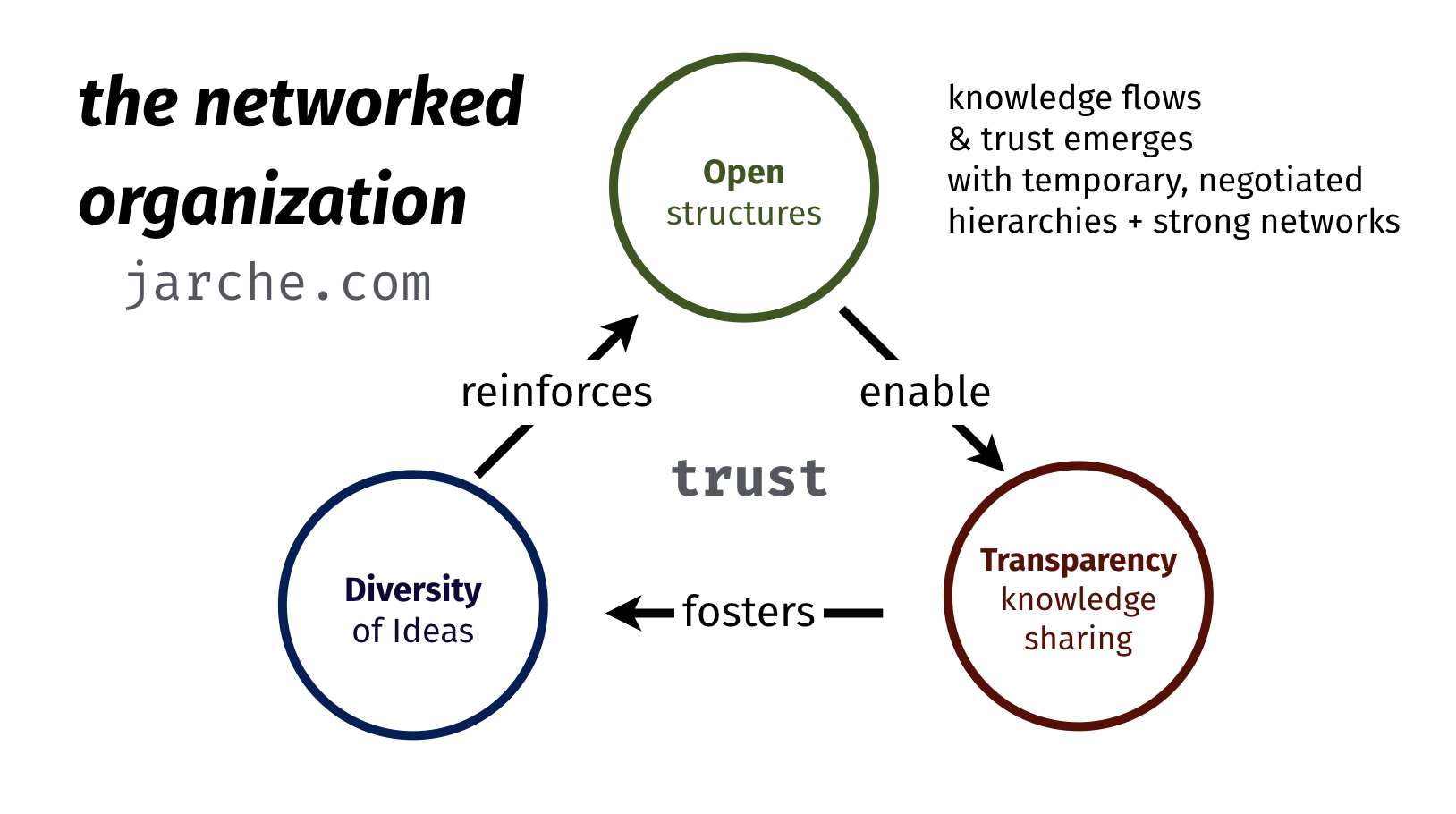

- From Harold Jarche, I have learned many ways of managing personal knowledge development through mindful connection to different networks in ways that ideally make them all “smarter” and don’t simply ask them/me/us to work “harder.” Of particular help is knowing what one can reasonably expect in terms of energetic flow and return from work teams versus communities of practice versus one’s wider social networks (see image above).

- Especially in work that may be emotionally challenging and draining, I have learned from both Acceptance and Commitment Therapy/Training, as well as teacher Tara Brach, the idea of “tending and befriending” otherwise unwelcome feelings that inevitably come up, so that rigid resistance does not make those emotional visitors stronger.

- And in general, I am embracing and making space for more silence, solitude and stillness, challenging some of my deep seated anxieties about losing connection and a sense of belonging in the world (what some would say FOMO is really about – for more about this, see this informative talk by Tara Brach).

And there are SO MANY teachers out there and much wisdom to glean that I certainly welcome others to share! It is my hope that many more of us can become adept energy and flow scientists/artists/healers/workers as we intentionally weave patterns that are the basis of the better world we sense is possible and know is necessary.

“The point of solitude is to give yourself time to grow in your own way, while the ultimate goal remains the difficult task of love and connection.”

– Damion Searls (from the introduction to a new translation of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet)

oringially published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate at the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC). Much of his work entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food, education, public health, and economic systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

The Web of Change

Creating Impact Through Networks

The following post is excerpted from the introduction of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change, now available in print, as an audiobook, and as an ebook.

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

— Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Since the beginning of our species, humans have formed networks. Our social networks grow whenever we introduce our friends to each other, when we move to a new town, or when we congregate around a shared set of beliefs. Social networks have shaped the course of history. Historian Niall Ferguson has noted that many of the biggest changes in history were catalyzed by networks—in part, because networks have been shown to be more creative and adaptable than hierarchical systems.[1]

Ferguson goes on to assert that “the problem is that networks are not easily directed towards a common objective. . . . Networks may be spontaneously creative but they are not strategic.”[2] This is where we disagree. While networks are not inherently strategic, they can be designed to be strategic.

When deliberately cultivated, networks can forge connections across divides, spread information and learning, and spark collaborative action. As a result, they can “address sprawling issues in ways that no individual organization can, working toward innovative solutions that are able to scale,” write Anna Muoio and Kaitlin Terry Canver of Monitor Institute by Deloitte.[3] Networks can be powerful vehicles for creating change.

Of course, networks can have positive as well as negative effects. Economic inequality and the advantages and disadvantages of social class, race, ethnicity, gender, and other aspects of individual identity are in large part the result of network effects: certain types of people form bonds that increase their social capital, typically at significant social expense to those in other groups. Much of the world has become acutely aware of the harmful network effects arising from social media and the internet. This includes the proliferation of online echo chambers that feed people what they want to hear, even when it means rapidly spreading misinformation.

In our globally connected and interdependent society, it is imperative that we understand the network dynamics that influence our lives so that we can create new networks to foster a more resilient and equitable world. The choice in front of us is clear: either we can let networks form according to existing social, political, and economic patterns, which will likely leave us with more of the same inequities and destructive behaviors, or we can deliberately and strategically catalyze new networks to transform the systems in which we live and work.

A case in point is the RE-AMP Network, a collection of more than 140 organizations and foundations working across sectors to equitably eliminate greenhouse gas emissions across nine mid- western states by 2050. From the time it was formed in 2015, RE-AMP has helped retire more than 150 coal plants, implement rigorous renewable energy and transportation standards, and re-grant over $25 million to support strategic climate action in the Midwest. RE-AMP’s work is necessary in part because other powerful networks are also at play to maintain the status quo or to enrich the forces that profit from pollution and inequality.

We can look to the field of education for another example of a network creating significant impact. 100Kin10 is a massive collaborative effort that is bringing together more than three hundred academic institutions, nonprofits, foundations, businesses, and government agencies to train and support one hundred thousand science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) teachers across the United States in ten years. Founded in 2011, 100Kin10 is well on track to achieve its ambitious goal and has expanded its aim to take on the longer-term systemic challenges in STEM education.

The Justice in Motion Defender Network is a collection of human rights defenders and organizations in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua that have joined together to help migrants quickly obtain legal assistance across borders. Throughout the ongoing family separation crisis created by US immigration policies during the Trump administration, this network has been essential in locating deported parents in remote regions of Central America and coordinating reunification with their children.

Or consider a network whose impact spans the globe, the Clean Electronics Production Network (CEPN). CEPN brings together many of the world’s top technology suppliers and brands with labor and environmental advocates, governments, and other leading experts to move toward elimination of workers’ exposure to toxic chemicals in electronics production. Since forming in 2016, the network has defined shared commitments, developed tools and resources for reducing workers’ exposure to toxic chemicals, and standardized the process of collecting data on chemical use.

Networks like RE-AMP, 100Kin10, the Defender Network, and CEPN—along with many others you will learn about in this book—were not spontaneous or accidental; rather, they were formed with clear intent. These networks deliberately connect people and organizations together to promote learning and action on an issue of common concern. We call them impact networks to highlight their intentional design and purposeful focus, and to contrast them with the organic networks formed as part of our social lives.[4]

We think of impact networks as a combination of a vibrant community and a healthy organization. At the core they are relational, yet they are also structured. They are creative, and they are also strategic. Impact networks build on the life force of community—shared principles, resilience, self-organization, and trust— while leveraging the advantages of an effective organization, including a common aim, an operational backbone, and a bias for action. Through this unique blend of qualities, impact networks increase the flow of information, reduce waste, and align strategies across entire systems—all while liberating the energy of multiple actors operating at a variety of scales.

All around the world, impact networks are being cultivated to address complex issues in the fields of health care, education, science, technology, the environment, economic justice, the arts, human rights, and others. They mark an evolution in the way humans are organizing to create meaningful change.

To learn more about what impact networks are, how they work, and what it takes to cultivate and sustain them, check out the new book Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change.

[1]: Niall Ferguson, The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power (London: Penguin Books, 2018), xix.

[2]: Ferguson, The Square and the Tower, 43.

[3]: Anna Muoio and Kaitlin Terry Canver, Shifting a System, Monitor Institute by Deloitte, accessed December 17, 2020, https://www2.deloitte.com /content/dam/insights/us/articles/5139_shifting-a-system/DI_ Reimagining-learning.pdf.

[4]: June Holley has called them “intentional networks” in Network Weaver Handbook: A Guide to Transformational Networks (Athens, Ohio: Network Weaver Publishing, 2012). Peter Plastrik, Madeleine Taylor, and John Cleveland have called them “generative social impact networks” in Connecting to Change the World: Harnessing the Power of Networks for Social Impact (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2014).

Originally published at Converge

David Ehrlichman is a catalyst and coordinator of Converge and author of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change. With his colleagues, he has supported the development of dozens of impact networks in a variety of fields, and has worked as a network coordinator for the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network, Sterling Network NYC, and the Fresno New Leadership Network. He speaks and writes frequently on networks, finds serenity in music, and is completely mesmerized by his newborn daughter.ehrlichman@converge.net

Reimagining a Regenerative Future — Part 1

Navigating radical uncertainty with radical tenderness…

MATURITY is the ability to live fully and equally in multiple contexts; most especially, the ability, despite our grief and losses, to courageously inhabit the past, the present and the future all at once. The wisdom that comes from maturity is recognized through a disciplined refusal to choose between or isolate three powerful dynamics that form human identity: what has happened, what is happening now and what is about to occur.

~Anais Nin (quoted in brainpickings; italics mine)

Never has there been the need to inhabit multiple contexts more than now — “to courageously inhabit the past, the present and the future”. The start of 2020 presaged chaos, collapse, and terror. In January, the megafires of Australia. In February, megafloods. In March, a deadly pandemic. No respite! The machineries of the world has collapsed and laid bare their fractures and fissures in the face of Covid-19 highlighting the appalling inequality, failed governments, spurious economic policies, failing and flailing nation-states, the exploitation, extortion, and extraction that runs the economy, the dehumanization of humans, and utter disregard for this fragile and beautiful planet.

2021 began with vaccines, which could and should have brought nations together with humanity prevailing over all surface differences to face a global challenge. Instead this degenerated into “vaccine apartheid” with wealthy nations like the USA and Britain opposing India and South Africa’s bid to waive Covid-19 vaccine patents. Vaccine hoarding is another game being played: “… though rich nations represent just 14% of the world’s population, they have bought up 53% of the most promising vaccines so far.” Rich countries hoarding Covid vaccines, says People’s Vaccine Alliance. What could have been a defining moment of compassion, connection, and care in the civilizational narrative turned into repulsive power play, politics, profiteering, and a show of brute strength and shocking neocolonial racism.

The dual traps of neocolonialism and neoliberal capitalism blinded leaders and nations to the most crucial lesson that the pandemic taught us. The infallible truth of our inextricable interconnectedness and interdependence with all sentient beings and this Planet. We cannot survive, let alone thrive, as long as a vast majority of the planet remains oppressed, disregarded, and disavowed. “All the catastrophes we face now are byproducts of a feeble, decrepit industrial-capitalist economy. All that is what capitalism really is — exploitation of you, me, the planet, life on it, democracy, and the future, by organizations wealthier than countries, with legal superpowers, whose only goal is to maximize profit, at any cost. How are we to cohere, prosper, survive, endure — grow?” ~ Umair Haque. One would have thought that the pandemic must have driven this lesson home when a microscopic zoonotic virus jumped species and ravaged the world. Apparently not!

The pandemic, nonetheless, was a point of discontinuity — a rupture in the seams of the already fraying civilizational narrative of universal and never-ending growth and development, the utopia of technology as savior, and the myth of the West leading the rest of the world on an onward march of progress. There have been many moments of disruption, but none spanned the globe with such a visible and terrifying impact bringing mighty nation-states to their knees and halting the juggernaut of the ostensibly unstoppable machinery of global economy. This rift threw up with blinding clarity the brokenness that lay hidden just beneath the surfaces of society, politics, and other machineries and machinations of civilization. The simultaneous collapse of essential systems across the globe — from healthcare and economics to politics and education — are visible evidence of an obsolescing and degenerating civilizational narrative. The depravity and decadence underlying the world order revealed themselves in all their shame.

2020 became an inflection point in the trajectory of the Anthropocene catapulting us directly into the liminal space of radical uncertainty for which we had no script. A space without stories to anchor us, a space of incongruities and paradoxes, of death and decay — a seemingly yawning chasm of obscurity. We were left grappling to make sense. In this interregnum, the questions we ask are crucial acting as compasses in an essentially map-less territory of radical uncertainty.

What if we could navigate radical uncertainty with fierce compassion and radical tenderness — for ourselves, for each other, for all sentient beings, for this beautiful, fragile Planet?

What would those choices and decisions made from a place of fierce compassion look like?

How would we envision our collective future from a place of radical tenderness?

In a 2015 Manifesto called Radical Tenderness, Dani d’Emilia and Daniel B. Chávez writes: “radical tenderness is to not collapse in the face of our contradictions… is to have peripheral vision; to believe in what cannot be seen.” The words are hauntingly evocative, prophetic, and profound. The chaos and conflicts threatening us daily are overwhelming, and it is easy to sink into despair and a desperate yearning for some semblance of stability and certainty. The pandemic can be a portal towards a regenerative future inviting us to hospice what no longer works, and to midwife the new. If only we can “believe in what cannot be seen”.

How can we collectively hold space for the new shoots to emerge from the debris and decay of this collapsing world?

How can we be stewards of those narratives that have been disowned and denied for centuries — those unheard, unseen, unacknowledged ways of being, seeing, sensing, and knowing which can be our salvation towards a regenerative future?

We know in our guts that there is no going back to the “old normal” if we want to survive as a species on this Planet we call home. We can also feel the quiet, ephemeral presence of the more beautiful world our hearts know is possible. “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing,” wrote Arundhati Roy.

The hegemonic narrative of growth, development, and modernity imposed through the imperial project of colonization — Eurocentric and Western — has not only been running the show for centuries but has sterilized and homogenized all other ways of being and relating on this planet. Donna Haraway called it “playing the god trick”. Now this “god trick” has spectacularly failed as it must. The ineffectuality of this monocultural worldview in a diverse and pluricultural planet is starkly visible.

By excluding, delegitimizing, and disavowing myriad ways of being, seeing, learning, and knowing that did not subscribe or partake in the mainstream, hegemonic, civilizational narrative, we failed to make sense of an inconceivably diverse world. The arrogance of this primarily Western cosmology and ontology being the only meaning-making device available to humanity is astounding in its presumption.

The pandemic is clearly an inflection point. The breakdown of the old order and its edifices are asking us to slow down, to connect with our inner wisdom, to lean into this liminal space of uncertainty and ambiguity, to widen our peripheral vision, and listen to Earth’s invitation to co-create a thriving, flourishing Planet — “a world where many worlds fit”. And maybe, just maybe — we will catch a glimpse of the shoots of the possible futures amidst the debris and decay of the dying.

Let us slow down and listen to the unheard, unnoticed, unappreciated voices and narratives signaling to us from the peripheries, from the edges of “civilization”. Voices and stories that have for centuries been marginalized, demonized, invisibilized — the oppressed, brutalized, and systematically persecuted voices of the human and the more-than-human. The sidelining was part of the project of colonization resulting in immeasurable loss, disconnection, and untethering for millions in the Global South. Global South is not a geographical location but a metaphorical identity that enfolds the unseen and the unheard, the disowned and the disavowed, the delegitimized, invisibilized, and demonized billions. Global South exists in the peripheries and margins everywhere. We become aware of them in movements like #BlackLivesMatter, #IndiaFarmersProtest, and many other local movements of dissidence and resistance that fly under the radar, are never reported, often brutally quelled — in short, effectively and methodically made invisible.

Why is it crucial to integrate the unheard, unseen, unfamiliar narratives into the new civilizational narrative of a regenerative future?

What is the essence of a world that contains multitudes of narratives — a world where many worlds fit?

How do we reimagine a regenerative future — a world where many worlds fit?

What are the founding principles and values of a Pluriverse?

When we acknowledge with humility that we can never know it all — that our knowledge will always be situated, contextual, and partial stemming from the land and its culture can we step into the emergent space of radical uncertainty with hope and humility. What we can do is listen with fierce compassion and co-create containers for fearless dialogues of possibilities.

Dialogues offer us opportunities to intertwine and interweave the myriad ways of being, seeing, and knowing. And dialogues also save us from the dangers of a single story. Dialogues offer us spaces for co-sensing and listening to each other.

~TEDx, The Story of the Global South

In the next part of the post, I explore the concepts of Pluriverse, and why is this necessary to shift the civilizational meta-narrative to one that is inclusive, compassionate, pluri-cultural, and regenerative. None of us have the answer, but we can collectively re-imagine a regenerative future by coming together in fearless dialogues — dialogues revolving around our hurts, our hopes, and our healings.

Article originally published here in The Age of Emergence

Sahana Chattopadhyay —Sahana Chattopadhyay is a global Speaker, Writer, Master Facilitator, Organization Development Consultant, and Coach. She works at the intersection of Complexity, Human Potential, Organizational Transformation, Systems Thinking, and Emergence. Her passion is to enable organizations to develop the capacities, skills, and mindsets to become “thrivable” in the face of uncertainty and ambiguityr, writer, facilitator, and story-seeker. (https://linktr.ee/sahana2802)

I am a part of the Possible Futures collective. I deeply acknowledge the many fearless dialogues here that have helped me shape my thoughts and birthed new ones.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

From Learning to Doing

How do more of us help create a world that is good for all of us? Many of us have been attending at least a few of the hundreds of enticing webinars that have been available during the last pandemic year, but somehow have not been able to actually apply what we have learned in our communities.

The first challenge has been that most of these webinars are what I call “talking heads:” one individual or a panel of experts share new ideas with us for the entire session. At the end we may realize that we have a million questions and have no idea how we might proceed. But we immediately move back into our workflow and the memory of the webinar content quickly fades.

I’ve even been part of sessions that are more interactive, where we are put into breakout rooms after the presentation and have a chance to reflect on the information provided. But somehow this, too, is not quite enough.

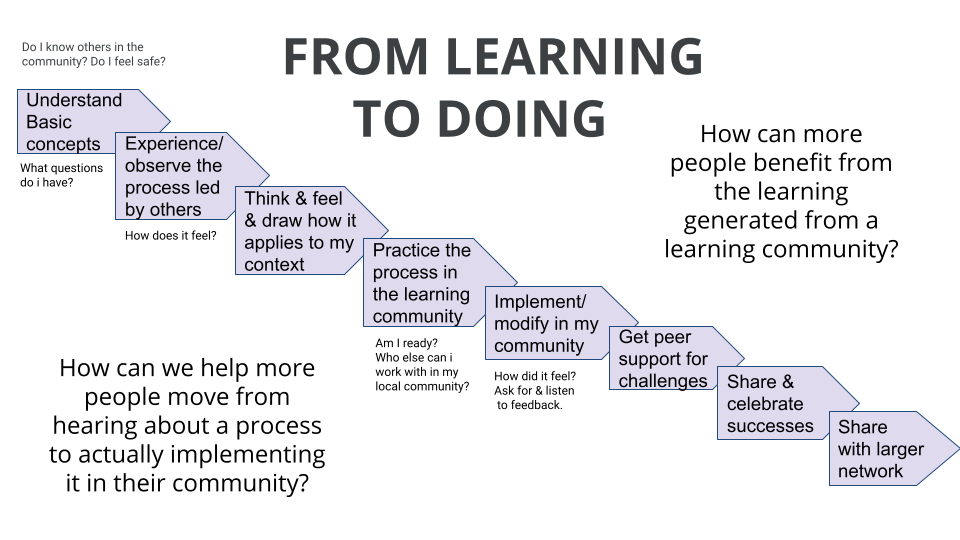

As a result, I thought about times when I , or people I knew, had actually managed to apply a new idea to their community. The very crude chart (would love some graphics assistance on this!) below shows that there are many small steps that need to be taken (and supported by capacity builders) for learning to move to doing.

Let’s go through the steps:

Create a learning community.

First, I think learning communities are the best place to be introduced to new ideas. A learning community is simply a group of people (using zoom such groups could actually be very large if good use is made of breakout rooms) who commit to meeting regularly (usually monthly) to support each other’s learning and doing. It’s wonderful if you can have skilled, paid facilitation of such a group but they work amazingly well with informal groups who share the facilitation role. Most learning communities have some sort of focus to their learning, i.e. they may be people who want to learn more about systems strategies or network weaving or food access.

An important part of successful learning communities is that people in them feel safe to share their concerns or challenges. This means that learning community facilitators will need to include relationship building activities in every session where people get to know each other more deeply.

Hear information about a new process, skill or strategy and have space to ask questions and reflect.

I have found that listening to something new is often overwhelming, so I recommend that presenters limit their talk to 10-15 increments. If the topic is complex, you might want to have two 10 minute presentations each followed by a breakout session of 5 minutes. People can generate questions during the breakouts that are captured on a jamboard or Miro board - and answered by the presenter(s) as they are written.

Do a demonstration.

It’s often very useful for presenters to demonstrate the new skill or process with an individual or small group, with the rest of the participants observing.

Practice in the learning community.

The next step is to actually practice the process in the learning community, or in some cases, you may want to set up a smaller popup session for practice.

Thinking/feeling about application.

It’s often useful, especially for introverts, to have some time by themselves processing their reaction to the process. Participants can be encouraged to notice how the process feels to them? Might it be a good fit with their community? Does the process seem hard or simple/ is it scary to think about doing something like this in their community? They can write notes or be encouraged to draw.

You might also give participants time to discuss potential application in a breakout room. Here they might answer questions such as, “How might this work in my community? Who else could work with me on implementing this process? Could I try it first with a small group of people? What is a meeting coming up where I could try this?

Participants then (if they plan to go ahead) make a commitment to try out the process or skill in the coming month.

Applying in your community.

Participants hopefully have worksheets etc to help them take the information back to their community. They also need to be encouraged to find one or two others to work with them on the application. An important part of their planning process needs to be thinking about how the process may need to be modified for their specific context.

An essential part of any process will be to allocate time for the groups’ reflection on the process.

Other worksheets can encourage the facilitation group to spend time after to reflect on the process: what worked well? What would we need to change? What challenges did we encounter that we didn’t expect?

Get peer support for challenges.

When the learning group next meets, ask if anyone experienced any challenges in applying the practice. If there are several, you might want to have each person with a challenge go into a breakout room with others to support them. Then share the peer assist process to help them think how to work with the challenge.

As facilitator, you will need to frame the request for challenges with the importance of seeing challenges as a way to deeper learning. This embracing of so called mistakes is a key part of the mindset shift we all need to make.

Celebrate successes and harvest to share with other networks.

Encourage one or two participants to share successes they had with the process - encourage them to share pictures to make their success come alive for others.

You may want to facilitate a knowledge harvesting process. Some people have had success using jamboard, Miro or a google doc where everyone can add what they learned from implementing the process, suggestions for changes or improvements, key factors for success and so forth. Encourage one or two participants to take this input and craft into a post or handout that can be shared by participants with all their networks and social media connections. They may want to include video snippets of the process or people sharing how useful it was.

Share with other networks.

If the learning community is part of a specific network with a communications ecosystem, encourage the information to be shared through newsletters and social media. You might also want to turn the information into a resource or handout, as we are doing with this blog post!

If there is a good response to the sharing of the information, you might want to set up a popup for others outside of the learning community on how to use the process in their settings.

Big Picture

What is this chart suggesting about training? It’s saying that if we want our training to lead to change in communities, we need to reconceptualize training to make it more interactive and supportive of all the steps that are needed to move from learning to doing. We will get so much more impact if we shift the emphasis from content (and this is very hard because we as teachers, presenters and experts almost always LOVE our content and feel people need to have access to every bit of it! You can still share a longer video or article with participants so they can dig in deeper) to an emphasis on support for application of new practices.

Next steps

I would love for people to comment on this article, add additional ideas, edit it - in other words, make it better! Please just click on this link and it will take you to a google doc where you can comment or edit. This blog post can be so much better with your thoughts added. Once we have collected and edited those new thoughts, I’ll revise this blog post.

I’d also love to hear how you share this post with others in your networks. Was it useful? Did you take any steps to shift your webinars so they are more interactive?

June Holley has been weaving networks, helping others weave networks and writing about networks for over 40 years. She is currently increasing her capacity to capture learning and innovations from the field and sharing what she discovers through blog posts, occasional virtual sessions and a forthcoming book.

featured image found here

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

The Wisdom of W.A.I.T.ing: Mindful Sharing in a Network Age

“We have two ears and one mouth, so we should listen more than we say.”

— Zeno of Citium

The other day I was reminded of the group working agreement “W.A.I.T.” (which stands for, “Why am I talking?”) as a guideline for people to be mindful of sharing air time in discussions. Since then I have been taking fresh note of my own inclinations and motives to not only talk in discussions, but also to share on social media. And as I have done this, I have also been more curious about what motivates others to share, verbally, in written and other forms. What are they thinking? Are they thinking about other people? If so, who? Have they thought through possible impacts? What do they care about?

I am a big fan of and subscriber to The Christian Science Monitor, which publishes a weekly digest of updates and perspectives on things happening around the globe, including (perhaps radical for these times) “bright spots” and “points of progress.” The editors and writers of Monitor articles also have a wonderful practice of publishing a little blurb for each offering under the heading “Why we wrote this.” How refreshing! What if all “news outlets” were to do this, or at least pause and ask this before writing and publishing/speaking?

And what if we were to do this in our different networks and communities? Might this help to break some of the spirals of othering and outrage (not to mention challenge the algorithms behind our growing social dilemma)? And shy of this, might the practice of W.A.I.T.ing or mindful and intentional sharing (viewed perhaps more generatively as “nourishing”) help people deliver on the promise of “network effects” to take communities and societies in a more prosocial direction?

I am currently working with two organizations over the course of 2021 to help staff and partners develop more networked ways of thinking and acting/being. Recently we had a discussion about how to keep the staff more up to date with respect to one another’s network weaving activities (connections made, crucial take-aways, immediate next steps) and also share other interesting content and connections. Trying to strike the right balance between radio silence and deluge, we started exploring how implementing the W.A.I.T/S. (Why am I talking/sharing?) prime might help. Along the way, a couple of people said that W.A.I.T/S. might also stand for “Why aren’t I talking/sharing?” and encourage the otherwise less inclined (for various reasons) to reconsider. This is stimulating rich conversation about how to tend and modulate important flows in various systems (organizational, community, school, etc.) to support learning, resilience, alignment, equity, emergence, coordinated action …

All this to say, whatever our goal(s) may be, it could be important to … W.A.I.T for it. This is how less conscious and helpful sharing (and silence) might become a practice of care-full curation (making thoughtful offers to and requests – sharing and caring can also include asking questions! – of one’s communities).

originally published at Innovation Interaction for Social Change

featured image found here

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate at the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC). Much of his work entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food, education, public health, and economic systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Thinking Like an Octopus (and With a Collaborative Heart): Evolving and Interlocking Networks

“You’ve got to keep asserting the complexity and the originality of life, and the multiplicity of it, and the facets of it.”

Toni Morrison

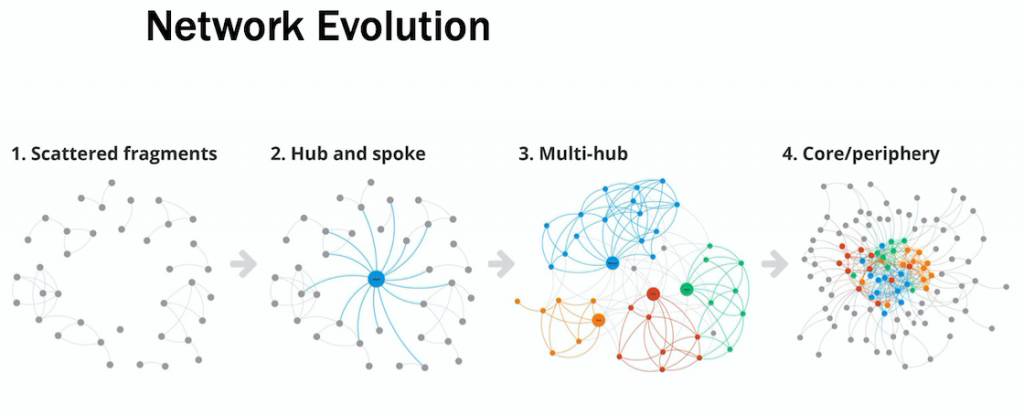

A network that I have been a part of for a number of years is seeing the emergent proliferation and strengthening of other related networks (some more adjacent than others) in its shared geographic and issue spaces. While this is welcomed overall, and sets up the potential for a more robust movement network and core-periphery structure (see image below), there are also some discussions within the network about how this proliferation constitutes an opportunity versus a looming threat or conflict.

There is plenty being written about the power of collaboration to solve complex problems and shift undesirable patterns, and one of the persistent barriers to collaboration is the default competitive and protective instinct found in individuals and groups. There are good and long-standing evolutionary reasons for “watching out for number one,” so this impulse can be fairly baked in. And there are also good reasons for understanding and leaning into “collaborative advantage” (see, for example, the work of evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson on multi-level selection).

“One step is to recognize that ‘ideologies extolling individualism, competition, untrammeled free markets, and conversely, disparaging cooperation and equality’ (as Turchin puts it) have no scientific justification. An unregulated organism is a dead organism, for the body politic no less than our own bodies.”

David Sloan Wilson

And of course, there are plenty of examples of “taking the high road” only to have someone else take advantage of this, which can leave us feeling like we are living in the prisoner’s dilemma. So what is a network to do? Well, if your values include collaboration and justice, then you do your best to lead by example. Which is where a recent network stewardship team conversation left us. And as often happens with this group, things continued to marinate and then one of our members sent the following beautiful email, reminding us of her experiences in a related network of networks.

“The dynamics we discussed reminded me a lot of what we have experienced at our organization since 2009, so if you’ll indulge me for a few minutes I’ll try to lay it out here. In late 2007, we piloted a new cooperative venture and launched the FL Collaborative in 2009. Our vision and aspirations were to bring a cross sector of people and organizations together to address the root causes of the problems facing our sector and relevant communities.

One of the first things the FL Collaborative really wanted to focus on was replicating the cooperative model, and our organization was tasked with doing that. And we did. Pretty soon it became clear that we couldn’t both do that and hold the bigger vision and aspirations. But to be honest, I didn’t want to admit that.

By 2011, the LC Network started to emerge from the FL Collaborative. My first reaction was that we have competition. But very soon it became clear that the LC Network was serving a role our staff and the FL Collaborative couldn’t serve. The LC Network was beginning to pull together elements of what it takes to shift the supply chain from one that is value-less to one that is value-full. The kind of technical support the sector and visionaries needed began to emerge through the LC Network.

By 2014, the SF Network (another network) began to percolate out of the FL Collaborative. And again I found myself triggered by the potential competition. What the SF Network was beginning to offer was the ‘social’ space. When our organization and the FL Collaborative were hosting a series of community gatherings and various social events that allowed us to have a public facing part, SF was emerging as being able to offer that. Another thing we could take off of our staff’s plate so we can focus on our bigger vision and aspirations.

The FL Collaborative, in the meanwhile, began to morph into the political and advocacy space. That’s where we think through policy shifts, organizing opportunities, connectivity, and alignment around the broader vision of what the future of the sector and larger system can look like and what it might take to get us there. Those who are engaged in each of these networks are doing things that they can easily wrap their heads around and inspires them most.

Today, I talk about these three networks as three tentacles of an octopus with our organization holding the space of the head of the octopus. Because our staff was not liberated to focus more fully on the shared values, bigger vision, the bigger story, connectivity, etc., all these three networks are interlocked by a shared set of values, a common vision, and organizing strategies.

Our staff are the ones who are asking the bigger questions of each of these networks when they seem to go off track. We are the ones who are finding the resources needed to get them to think about how racial equity is or isn’t showing up there (and we get most of that from [the network for which the readers of the email are the stewardship team]). So without sounding too egotistical, our staff is tasked with holding the moral center of all of this work whether it comes to the connections, strategies, resources, stories, organizing, etc. There is probably a better word than the moral center, but that’s the only thing that is coming to me right now.

More tentacles might emerge, and I hope they do as we identify gaps in this work. And I hope I can remain humble enough to not see them as competition but as a valuable addition to the family.“

It takes work, real intention and effort, to stay grounded and humble, to practice discernment and to keep perspective, to keep asserting the larger picture of complexity, to honor the need for deeper collaboration and more allies, to have faith in the possibilities that we cannot yet see through the growing entanglement of intersections. Even better when you can depend on others to help you out with this! With #gratitude to so many.

“Weave real connections, create real nodes, build real houses.

Live a life you can endure: Make love that is loving.

Keep tangling and interweaving and taking more in,

a thicket and bramble wilderness to the outside but to us

interconnected with rabbit runs and burrows and lairs.Live as if you liked yourself, and it may happen:

reach out, keep reaching out, keep bringing in.

This is how we are going to live for a long time: not always,

for every gardener knows that after the digging, after

the planting,

after the long season of tending and growth, the harvest comes.”

Marge Piercy, from her poem “Seven of Pentacles”

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Featured Image from Giulian Frisoni

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate at the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC). Much of his work entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food, education, public health, and economic systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Trust Emerges Over Time

Imagine a research-intensive organization where scientists should be sharing what they learn, and the official company policy is to share information and expertise among public and private partners. However, the company is ‘downsizing’ and layoffs are based on performance reviews. If one scientist helps a peer develop a patented product, and as a result the peer gets a better annual review, then the former may end up losing their job during the next round of layoffs. This was the situation I found myself in a decade ago.

Sharing knowledge was not a good personal strategy in this work environment even though it was official policy and was the focus of our project. We could not achieve our project objectives because systemic barriers pitted workers against each other in order to remain employed.