We need to talk about leadership

Visionary collective leadership to build a world where everyone belongs

What is the quality of leadership we need to build a world where everyone belongs?

I’m specifically interested in that ineffable quality of visionary collective leadership: the rare capacity to inspire and transform a collective to whom you are not in direct relationship. I think here of social movements, especially those which transcend borders: the universal emerging from the particular (Occupy, the Arab Spring, #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, etc.).

It feels so important to me that we get this “right.” While there has been talk of a leadership crisis for decades, I’m particularly concerned with the contemporary manifestation that is undermining our movements for justice. In Moe Mitchell’s ground-breaking diagnosis last year he cited “anti-leadership attitudes” as a core impediment to the transformation we seek. We desperately need bold leaders capable of caring for the whole… what does that quality of leadership look like? How can we cultivate it?

Here’s where I’m coming out (TL;DR): Visionary leadership is the capacity to take responsibility for using power to care for the whole. It is the relational capacity to offer an embodied invitation and a unifying narrative, in accountability to the whole.

To exercise leadership is to offer a gift: a gift that seeks to unlock and channel the gifts of others. To offer that gift is to assume responsibility for the whole, and therefore to accept accountability to the whole.

“Leadership is connecting what was separated”

I love this definition from Marcella Bremer, channeling Otto Scharmer. This feels like a great starting point for leadership that builds belonging, which in my understanding is about restoring connection and returning to wholeness. This provides the prism through which I want to explore leadership today, and the central metaphor through which I understand this work: it’s about building bridges.

In sifting through the literature on leadership for a definition that resonates with how I understand it, I came across this from Kevin Kruse:

Leadership is a process of social influence, which maximizes the efforts of others, towards the achievement of a goal.

I think this definition offers a solid foundation for our inquiry, and it’s worth unpacking; I’m including here some parenthetical notes about how this definition lands with me and the direction I want to take it:

- leadership is a process (not just what but how)

- of influence (it’s about power)

- it is relational (in service of a collective)

- it is about inspiring others to do their best (unlocking gifts)

- and it is in service of an outcome (pointing the way forward)

I will unpack each of these components in turn before offering four additional aspects that feel important to how I understand this quality of visionary leadership:

- not leading followers, but inviting co-creators

- leading as an embodied invitation

- offering a collective narrative

- in accountability to the whole

Admittedly, a definition of visionary leadership that includes nine components may be a little bold: too many ornaments on the tree, I fear. The point in enumerating them, for me, is to illuminate different domains of practice. I aspire to be the kind of leader who builds belonging, but I have so few models of what that looks like in practice that I often feel like I’m floundering in the dark. This is an effort to provide some light.

Visionary leadership is about process… and product

I struggled with this point for awhile, before finally arriving at this distinction: there is process leadership, and there is outcome leadership. They are different qualities, and each important in their own right; but the quality of visionary leadership I’m talking about requires both. [To be clear: there are many other types of leadership, all of which are vitally important; Alanna Irving offers a helpful overview here. For the purposes of today’s post, I’m focusing specifically on visionary leadership, as distinct from these other forms.]

Process leadership is goal agnostic; the goal is the process. This is facilitation, or mediation; Patricia Wilson defines it as a core attribute of the practice of Deep Democracy:

Process leaders create the container for building trust and shared understanding amid diversity and difference.

This work is necessary, but insufficient: we also need goal-oriented leadership. As Ericka Stallings recently put it:

Leadership is taking responsibility for getting things done.

This outcome focused definition to me is more akin to what I think of as management, or implementation. Also vitally important… but incomplete. Visionary leadership, as I understand it, must include both.

And: the means and ends must align. How we get to our goal is essential to getting there: we can’t strike the rock and hope to make it to the promised land.

Leadership is the right use of power

All definitions of leadership speak to influence: the ability to get people to do something. To me this is about wielding power. Cedar Barstow, who wrote a book on the “right use of power,” defines it like this:

Any use of power that does any or all of the following: prevents harm, reduces harm, repairs harm… to evolve relationships and promote sustainable well-being for all.

So that’s our baseline (power to a pro-social end, as distinct from power as domination). But the right use of power in visionary leadership I think requires four other components:

- It is about using your power as a leader to increase the total amount of power available. Power is not zero-sum: a core function of leadership is to generate new power, to unlock latent discretionary energy in individuals and the system. (I love Eric Liu’s work on the idea of power as abundant). This is the core work of organizing.

- It is about addressing how systems of oppression impact the existing power available to people. Oppressive systems harm both marginalized people by denying their intrinsic power, and dominant groups by granting them a toxic form of “power-over.” This is the core practice of what Change Elemental calls “deep equity”: working with privileged people to relinquish power-over, and supporting marginalized people to step into their personal power. Hahrie Han put it beautifully:

At the core of organizing is not just getting people to take action but instead it’s engaging people in a transformative process through which they develop their own leadership and their own capacity to make change.

- It is about channeling this unlocked power. Power is potential: nothing changes until that power is applied in service of something. This is where vision comes in, and direction (discussed below).

- It is about relinquishing your power. Ah, here’s the paradox: there comes a point where for the leader to continue to hold onto power can be a drag on the total power available in the system. Because once others have accessed their own power, they now need to influence the direction: they are no longer “followers” but co-creators… and the original “leader” needs to shift into a new role (not letting go of leadership, for which I think there is always a need, but for letting go of power as initially practiced). More on this below. I’ve been sitting with this line from Laszlo Bock, commenting on what it means to lead in the 21st century:

What’s critical to be an effective leader in this environment is you have to be willing to relinquish power.

Leadership is relational and collective

This is an obvious but under-emphasized point: to lead is to be in relationship to whomever you are purporting to lead. As the West Wing famously noted (I’m sad this video clip isn’t on YouTube, and HBO won’t let me upload it):

You know what you call a leader with no followers? Just a guy going for a walk.

Celine Schillinger goes so far as to describe leadership as a “collective capacity.” I take her point: all leadership is relational and shaped by the context we find ourselves in. And: the quality of leadership I’m focused on here is an individual capacity enacted in a collective context.

There are two extremes I’m reacting to here: one is the Western aggrandizement of the individual leader, the cult of personality that is the opposite of what I think is needed (see Musk, Elon). This approach to leadership centers the “I” of the leader (often in dangerously egocentric form), and the expression of that “I” through the organization they’ve founded… and either ignores or deprioritizes the needs of other people in the organization/world. But the other extreme is the often-lauded concept of servant leadership; the oppositional response the the apotheosis of the “I.” Where traditional American dominant culture leadership centers the “I,” servant leadership centers others, or the collective. Robert Greenleaf, who coined the term, explains:

The servant-leader puts the needs of others first.

The quality of relational leadership I’m seeking declines to accept this false binary. I don’t think we can be effective leaders if we aren’t in touch with our own needs and desires. Both because we will burn out (self-sacrifice is not sustainable), and because we are depriving the collective of our vision: we forget that “I” is part of “We.” Paradoxically, to not speak for our needs (servant leadership) is to undermine the collective. And of course we can’t be effective leaders if we are only in touch with our needs, without caring for others or the whole: that isn’t leadership, that’s narcissism.

I aspire to a form of leadership that is interdependent. It’s no surprise that our colonial language has words for selfish and selfless… but not self-full: the very idea of interdependence under systems of oppression is in a literal sense inconceivable. The quality of leadership I long for instead seeks to simultaneously meet the needs of everyone: what in Building Belonging we call I, We, World. In this understanding we don’t put anyone’s needs “first”; rather, we hold them all as equally important and not opposed. As nonviolent communication reminds us: needs are universal, and never in conflict.

Leadership is about unlocking gifts

This to me has always been the core of how I understand leadership. It’s related but different to the point around power: it’s not just supporting others into tapping into their power…. it’s about helping people identify and share their gifts. This to me is the subtle but important difference between “servant leadership” (which subjugates the self) and leadership that is of service: grounded in the I, connected to the We and the World. Rachel Naomi Remen has my favorite treatment of this distinction, explaining:

We can only serve that to which we are profoundly connected… Serving makes us aware of our wholeness and its power. The wholeness in us serves the wholeness in others and the wholeness in life.

The key point here: we actually can’t be of authentic service (we can’t lead) if we aren’t deeply connected to ourselves… grounded in the “I.” Dominic Barter’s exquisite meditation on empathy really captures this idea for me (thanks to Miki Kashtan for introducing me to his work). The whole thing is worth a watch: so much wisdom and insight packed into a few short minutes. The definition of empathy I want to highlight here:

Lending my sense of them back to them... that helps them connect to themselves in a deeper way… That inner connection is within myself, and that inner connection allows me to engage with someone else without me being submissive to them or attempting to dominate them.

I would echo Dominic and go further: we need others to help us identify and share our gifts. I don’t think—especially as we are socialized into cultures of domination—that we can fully grasp our own gifts without them being refracted back to us through someone else’s lens. Indeed, it is this act of what Dominic calls empathy and Rachel calls service that I consider the foundational act of leadership. It is to offer the first gift: to give others the radical gift of being seen and celebrated. I love Robin Wall Kimmerer’s writing on the power of gift:

Leaders are the first to offer their gifts... leadership is rooted not in power and authority, but in service and wisdom… This is our work, to discover what we can give. Isn't this the purpose of education, to learn the nature of your own gifts and how to use them for good in the world?

Yes. Building on my last post: it is to make others feel like they belong. It is that felt sense of belonging (which includes safety) that allows people to unfurl, to blossom, to acknowledge to themselves and share with others their gifts. Thinking about this post I was pleased last week when picking up my kids from elementary school to see this poster in the cafeteria:

Yes. And it is a fundamental task of leadership to help people identify their unique gift and contribution.

Leadership points the direction…

Unlocking gifts is necessary but insufficient. To unlock gifts is the work of an educator. A leader goes a step farther, and channels those gifts in service of the whole. It is this aspect that distinguishes visionary leadership from process or facilitative leadership.

But: to lead in a direction is not to direct; there is a quality in visionary leadership that is distinct from the “goal leadership” of traditional management structures. I like this nuance from Simon Sinek:

I also like the implication here: it’s not about a destination (a defined outcome), it’s about a direction. There is something important about the ability to chart a course through complexity, to navigate uncertainty… a quality that some have called “emergent leadership.” This is the “visionary” part of visionary leadership: it is seeing a path that others do not yet see. In my last post focused on visionary leadership, I talked about visionary leaders as “human signposts” (following Vincent Harding): illuminating the path forward without necessarily defining where it ultimately leads.

There’s something important here about humility: the kind of groundedness that comes from embodied presence and clarity of vision… paired with the recognition that of course the “leaders” doesn’t have all the answers. Adam Grant calls this “confident humility.”

…and invites others to shape the path (co-creators, not followers)

We’re now expanding the definition of leadership that we started with. I’ve unpacked and added nuance to the five elements Kevin Kruse named, and now want to introduce four other ideas to complete my inquiry into the qualities of visionary leadership that build belonging. The first concept I want to offer here is the invitation to co-creation: it is the piece I struggle with the most.

True visionary leaders recognize that leadership is not about seeking followers, but about inviting others to share and shape the vision… and the direction. The goal is to build a movement, not an empire (a line I first heard from john a. powell). Visionary leaders may point us in the right direction, but ultimately we must walk the path. We cannot stay in the follower role. As Gloria Anzaldúa reminds us: “we make the bridge by walking.”

This was the struggle I took up in my last post wrestling with visionary leadership: it’s that perennial tension between holding on (right use of power as leader to catalyze collective action: illuminating the path) and letting go (relinquishing that power to relax into co-holding and co-creating: joining others in walking that path, and together creating the bridge). Let go too soon, and no one sees the path, or feels emboldened to commence the journey into the unknown. Hold on too long, and people never develop the capacity to build the bridge and shape where it goes. And of course, the visionary leader cannot alone determine the destination; in this I differ from the Source work that Tom Nixon has been synthesizing, building on Peter Koenig (though I find it insightful!)

I recently came across a couple ideas that feel like they get at the quality I’m seeking here. I haven’t found a name for it, which is part of what makes it so hard to describe: it’s not quite co-visioning, but it’s something like that. adrienne maree brown recently explained:

There is a difference between inviting you to join my imagination, and sharing your own imagination to see where we might meet.

Yes. Richard Rohr expressed a similar sentiment in sharing his vision for the world, and for building transformative movements. I love this distinction between followers and fellow travelers:

Not people who love me, but people who love what I love.

I’ve had the experience a couple times now where the audacity of my vision is not only welcomed but reciprocated by fellow bridge-builders… and it’s nothing short of delightful. Where I can offer the fullest expression of my gifts, and experience the power of others offering theirs. This is Norma Wong’s invitation in action:

How do we stay in relationship with each other's gifts?

To do so well is an artform (work in progress for me!), and simultaneously incredibly difficult and incredibly liberating. This is what I think Miki Kashtan was getting at when she observed:

The deepest form of human wisdom is mutual influencing.

Visionary leaders tell a good story

The second thing I want to add to Kruse’s definition is the importance of telling a good story. Jay Van Bavel names this explicitly:

One of the most important roles of leaders is creating a narrative.

Yes: humans learn through story; we make sense of the world through narratives. Jacqui Lewis cites Howard Gardner’s foundational work, explaining:

Good leaders tell compelling stories that change the stories in the minds of followers.

Here Lewis conceives of storytelling as an act of transformation: it is the invitation into a new worldview, a new way of making sense of the world and our role in it.

I’ve come to believe that there are three components to an effective narrative, which guide my work in Building Belonging. First, it must aid with sensemaking: it must help the listener/audience understand the world as it is AND their role in it. Second, it must include an invitation to imagination: to temporarily cast off the shackles of the status quo to situate ourselves in a different and better future. It is to remind them (and ourselves!) of Paulo Coelho’s radical truth:

People are capable, at any time in their lives, of doing what they dream of.

Third, it must offer a path from here to there: a bridge from painful present to delightful future. Writing on my personal blog way back in 2012 in an extended reflection on moral leadership, I said this:

A successful leader builds a narrative both around what is wrong (problem definition) and a path to a solution.

To build a narrative is to build a world: it invites people into a different understanding of reality. And most importantly: it invites them into agency around creating that new world and reality. I like this line from former IBM CEO Ginni Rometty:

Building belief is about moving people to embrace an alternate reality for themselves and others, and then to willingly participate in creating it. It’s the first major step if you want people to change, because they have to understand and believe in the change. (emphasis in original)

Leadership embodies the invitation

The third thing I want to add to Kruse’s definition combines two ideas. The first is to conceive of leadership as an act of invitation: if we are serious about building a world without coercion, we must practice it from the beginning… by inviting people into choice. I love Richard Bartlett’s simple offering here:

Leadership is the capacity to make a compelling invitation.

This to me is the central capacity of generating new power in the system, of what I think of as positive-sum leadership. Alanna Irving, a collaborator with Richard in the Enspiral project that has birthed so many lessons on emergent leadership, explains:

Invitations to responsibility can create space for others to achieve.

Second, that invitation must be embodied. This is so often what separates good leaders from great leaders, and remains a source of deep aspiration for me personally. I understand the need intellectually to embody the invitation. But as always, my cognitive understanding is far faster than my body’s capacity to integrate and embody… sigh, work in progress. Reviewing Howard Gardner’s work, Warren Bennis notes that one of the four distinctive qualities of leadership is:

A relationship between the stories leaders tell and the traits they embody.

Right. Humans have a deep and visceral ability to attune to body language and detect incongruence. This is why we are so drawn to magnetic figures like Barack Obama, whose public narrative was so powerfully embodied in his own story and body. This is the art of embodied leadership, and thankfully we’re slowly waking up to how fundamental this is to the entire enterprise. Places like the Strozzi Institute or generative somatics, and new offerings like Prentis Hemphill’s Embodiment Institute are seeking to meet this emerging demand.

To exercise leadership is to be accountable

One final idea here before I close. This to me is the natural companion to the notion that leadership is collective: to act on behalf of the whole is to be accountable to that whole. So often in dominant culture renderings of leadership there is no accountability, or if there is it only flows from those on the bottom to those on the top: did you meet your deliverables, did you do the thing I asked (or told!) you to do. To me leadership properly understood is mutual and accountable: the leader invites from a place of noncoercion, and in accepting responsibility accepts accountability.

This is partly why leadership is terrifying for so many: in our punitive carceral culture, we don’t have practice with accountability inside of interdependence. I loved this whole interview with Nwamaka Agbo, but this line in particular continues to resonate:

We don't know what it means to lead, until we have to make difficult decisions and take accountability and responsibility for the consequences of those decisions.

Here’s how I see the flow: first, to have a gift is to have responsibility to offer that gift. As Robin Wall Kimmerer reminds us:

Duties and gifts are two sides of the same coin… A gift is also a responsibility.

Second, because all gifts properly understood are in service of the whole, to offer that gift is to take responsibility for the whole. Miki Kashtan sees this as the defining characteristic of leadership:

The willingness to take responsibility for and care for the whole in interdependent relationship with others.

Third, to take responsibility is to invite accountability: in serving the whole, we become accountable to the whole. Peter Block calls this the foundation of accountability, explaining:

Accountability is the willingness to care for the whole.

Laureen Golden helped inspired this reflection in me with a recent post, where she offers this definition:

Leadership is a quality of presence that enables us to be responsible and response-able; it's a capacity to connect with and be guided by the animating force of Life. (emphasis in original)

This is subtle stuff: we are accountable both to the We (the collective to whom we are offering our gift of leadership), and to the World… in service of life itself. Ideally these are integrated and the same thing… but of course we humans have our own traumas, shadows, projections. So we must learn to discern between the invitation to appropriate accountability (in touch with source, attentive to impact) and the faux accountability that we rightly critique in “cancel culture.”

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at building belonging

featured art by Paul Akiiki: We Belong Together

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Coaching for Awareness-Based Systems Change

In the fall of 2019, a few of the founders of the Illuminate network (including CoCreative, Garfield Foundation, McConnell Foundation, and Academy for Systems Change) collaboratively hosted a gathering of systems change “capacity-builders” who work as independent consultants or in small collectives as facilitators and advisors, from the US, Canada, Mexico, UK, EU, and First Nations. This was the first time these practitioners had been invited to meet together with peers to share their perspectives on the state of the field. The North American contingent of the group continued on through the upheavals of the pandemic, meeting virtually in 2020 and 2021 to explore themes of equity and integrating health and healing into systems change practice, as well as launching a pilot pairing senior and emerging practitioners to explore what systems-centric approach to leadership coaching might look like.

CLICK HERE to learn more about this unique systems coaching pilot or visit the Network Weaver resource page to download the full article.

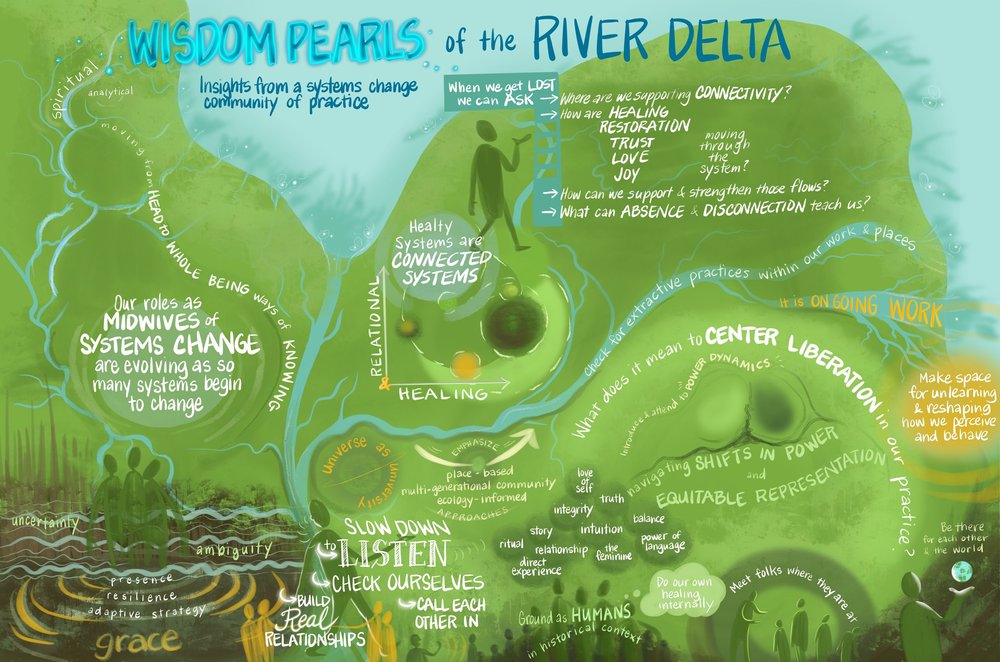

Check out the infographic below for some of the key insights from their COVID-era dialogues on the state of the field of systems change.

Learn more about the wisdom pearls HERE

You can also download a pdf with a link to this information to save to your personal library by visiting the Network Weaver Resource Page.

Katy Mamen is passionate about participatory change-making approaches that account for the complexity of multiple, interconnectedness crises and diverse lived experiences. She brings thoughtful and committed partnership to social sector clients advancing transformative systems change, drawing on expertise in social change strategy, facilitation and group process, systems theory, collaborative networks, and organizational development. In addition to process expertise, her work is informed by a strong background in economic justice, food & farming, water issues, and rural equity.

Brooking Gatewood helps leaders and groups clarify and enact the change they want in themselves, in their workplace, and in our shared world. At heart, her work is about co-liberation from systems of ‘power over’ and moving toward systems of ‘power with’ that honor individual agency as well as collective interests and wisdom. In practice, her coaching and consulting focuses on transformation across levels - from individual and team mindsets and behaviors to large-scale policy and systems change.

Originally published at IlluminateSystems.org

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Experimenting Towards Liberated Governance

Over a year ago, Vu Le published an article about the current models for nonprofit boards. The title “The default nonprofit board model is archaic and toxic; let’s try some new models” doesn’t bury the lede. Of the current models, Le writes:

“Over the years, we have developed a learned helplessness, thinking that this model is the only one we have. So we put up with it, grumbling to our colleagues and working to mitigate our challenges, for instance figuring out ways to bring good board members on to neutralize bad ones or having more trainings or meetings to increase ‘board engagement.’”

At Change Elemental, we have been experimenting with some new governance models, informed by the work of our clients, partners, and many others in the field who are trying out new structures and ways of governing. For example, Vanessa LeBourdais at DreamRider Productions has shared principles and practices of “evolutionary governance”, and Tracy Kunkler at Circle Forward has supported our learning about consent-based decision making. Countless other groups who have continued to uphold and practice historic, ancestral, Indigenous, and intergenerational structures of governance—and have informed these other values-aligned governance models—have catalyzed our learning.

Here, we offer a specific window on the evolution of our board, including some practices we’ve dreamed up, borrowed, and re-remembered to align governance with our values in a nonprofit system set up to default to white supremacy, paternalism, power over, and other oppressive habits.

The following questions have formed the basis of our governance and leadership evolution (we’ve shared more about our leadership evolution in recent blog posts here and here):

- How might we realize deep equity and liberation in leadership and governance?

- How might we evolve leadership and governance structures to share power and work in more networked ways?

- How might we align leadership and governance practices and culture with our values?

Our journey began a few years ago when our board and core staff team began to get curious about what it might look like to think about our board as mycelium. Mycelium are fungal networks that spread across great distances within soil (and sometimes underwater) and process nutrients from the environment to catalyze plant growth, supporting ecosystems to thrive. In our context, we use mycelium to refer to the powerful network of tendrils and roots that connect our board and core team to other people, groups, and organizations, enabling us to turn toxins into nutrients and nourish ourselves through our relationships to ensure collective thriving and care.

Here is what we’ve learned so far in our governance evolution (from the core team perspective—more from our governance team coming soon!):

Shifting language from “board” to “governance team” helped us reframe the governance team’s role.

Early on we shifted from referring to our board as “a board of directors” to a “governance team.” Tracy Kunkler of Circle Forward offered this definition in a small group experiment on governance we facilitated:

“Every culture (in a family, a business, etc.) produces governance — the processes of interaction and decision-making and the systems by which decisions are implemented. Governance is how we set up systems to live our values, and leads to the creation, reinforcement, or reproduction of social norms and institutions. Governance systems give form to the culture’s power relationships. It becomes the rules for who makes the rules and how.”

Shifting language supported us to shift our mindsets about governance. This language guided us towards greater clarity about our own governance team’s role: co-creating systems and practices that can support and catalyze us to live our values. It also deeply shifted how we both hold and reimagine the boundaries between the 12 people on our governance team, our core team (staff), and other partners to be more porous and center collaboration, emergence, and our interconnectedness.

However, because shifting mindsets requires shifting patterns and practice, this switch in language isn’t simple. We have noticed that we sometimes revert to using the term “board” rather than “governance team” when we are talking about potential barriers that the board may present or “traditional” board responsibilities such as fiduciary oversight. This is a work in progress and when we find ourselves reverting to old language, it is a signal that we might be in older practices, patterns, or ways of thinking about our relationship to the governance team and its role that are no longer serving us or our work.

Practicing liberatory governance is having one foot on land and one in the sea.

Getting clearer on our governance team’s role deepened our sense of what it might look like to realize deep equity and liberation in governance. We began to understand what “liberatory governance” could look like for us—a governance team that partners with us to bridge between current reality and the future we’re building by: moving the organization towards greater alignment with our values; and co-creating liberatory systems and ways of working together that can transform the larger oppressive systems we’re operating within. We talk about this internally as “having one foot on land and one on water,” a metaphor Hub member Elissa Sloan Perry shared from Alexis Pauline Gumbs. Gumbs hears best with “one foot in the water, one foot in the sand.”

In our organizational context, the “water foot” attends to things like our vision, uninhibited aspirations, values alignment, and acting today in ways that prefigure the world we want to see. The “foot on land” takes into account the world as it is, such as the requirements and legal constraints of our 501.c.3 tax designation, and current financial realities and access to other resources, where trust-based relationships can sometimes become transactional or even litigious. Our governance model values both “feet” in its awareness and decision-making. When we make decisions, the “water foot” leads with the “land foot” as a valued, supporting, and crucial partner.

Creating multiple, fluid points of connection across the staff and governance team helps build the relationships and trust necessary for shared leadership and power.

Building trust and mutual accountability are at the heart of our evolving governance structures and practices, just as we have found it to be in building toward shared power and leadership at the staff level. This work is more time-consuming than conventional governance models so we needed to build our collective capacity for sensing what is actually too much time. We also needed to strengthen our skill and capacity for generative conflict including discerning when to: enter into conflict and tension; sit with it so that we can reflect and discuss later; and/or intentionally let it go. This has meant getting more comfortable with sitting in discomfort when conflict can’t (or shouldn’t) be resolved immediately.

Some simple structures and systems support us in developing these capacities and discerning what is needed to build trust and move through conflict. For example, we wanted more interaction between our core team (staff) and the governance team, but didn’t want to necessarily add more large group meetings—we wanted connections to be deep and purposeful. To create purposeful connections, where a broad range of staff and governance team members could develop relationships and bring their unique gifts, we opted to have governance team co-chairs work with a staff liaison. The staff liaison partners with different staff, bringing different people into conversations with the co-chairs and other governance team members where their experience, wisdom, and gifts are critical. The co-chairs and other governance team members then connect together and separately into different areas of work based on their interests, skills, and what is needed.

We also evolved our governance team meeting structure to have staff members join for key sections of the meeting. We share the agenda in advance and offer some guidance to help staff decide when they might join or when they might opt out of a meeting. Additionally, staff and governance team members now caucus separately at the end of each governance team meeting to debrief and raise unresolved issues with the intention of sharing back what needs the full group’s attention. The caucuses support greater truth-telling across the governance team and core team, deepen our understanding of each other’s perspectives and help us dig into conflict with love and rigor.

Grounding in shared values is critical for practicing liberatory governance.

If you were to review the specifics of our governance team’s role, you might not find anything surprising or “new.” The difference is in how the governance team carries out these responsibilities – with a rooting in shared values with staff and commitment to working through differences in values when they show up.

In recruiting and engaging governance team members, we haven’t just sought out individuals who conceptually agree with our values (which were reflected in our recruitment criteria), but people who are game to experiment on what it looks like to make decisions rooted in those values. People who already embrace and practice inner work, multiple ways of knowing, experimentation, and emergent strategy—and who are looking to upend traditional governance team models and create and remember anew.

Even with the perfect container, structure, and systems, it’s the people who make up our core team (our staff) and governance team – their own values as well as their willingness to be in the generative tension that helps support shared values – who have accelerated our work in shared power and leadership both on the core and governance teams. Together, we are living into our vision and deepening our practices of shared leadership and shared power to shift conditions towards love, dignity, and justice.

Look out for more learning from these experiments in liberatory governance in the new year!

Natalie Bamdad (she/her/hers), joined Change Elemental in 2017. She is a queer and first-gen Arab-Iranian Jew, whose people are from Basra and Tehran. She is a DC-based facilitator and rabble-rouser working to strengthen leadership, organizations, and movement networks working towards racial equity and liberation of people and planet.

Mark Leach (he/him/his) has over thirty years of experience as a researcher and management consultant. Mark has a particular interest in strategy, leadership development and transition, and issues of equity and inclusion in organizations.

Originally published at Change Elemental

Banner Photo Credit: Kirill Ignatyev | Flickr

THE TAPESTRY: Weaving Life Stories

You are invited to listen to The Tapestry Podcast.

The podcast is about bringing people together to explore the rich, woven textures of our narratives. Our stories are impactful and in listening to the stories of others, we learn more about our own power, claim our purpose and pursue our passion. The fabric of our lives as women is strong, resilient and when we come together, we can make a beautiful piece of work to inspire, support and sustain our personal and professional lives. Although designed for women 50 and above, the wisdom shared is ageless. Join us as we share, laugh hysterically, cry, and keep it real all at the same time.

Some of The Tapestry's most recent episodes include:

THE STORIES BEHIND THE DATA - Meme Styles

In 2015, Meme Styles founded MEASURE to promote the use of evidence-based projects and tools to tell real-life stories behind the numbers. As a catalyst for systems change, MEASURE has grown to a fully operational nonprofit social enterprise that provides free data support to Powerful Black and Brown-led communities. So far the organization has provided over 3000 free data support hours to Black and Brown - led organizations.

CREATING A PERSONAL NETWORK FOR TRANSFORMATION -- June Holley

June Holley has been weaving networks - and helping other learn to weave networks – for over 40 years. Much that she learned is included in The Network Weaver Handbook, 400 pages of simple activities and resources for Network Weavers. She also created www.dev.networkweaver.com, a site with many free resources and a blog authored by over 40 network weavers.

BOUNDARIES IN BUSINESS AND IN LIFE FOR 2022 - Kimberly Oneil

Kimberly O'Neil is an award-winning professor, executive leader, and social good expert. She was the youngest serving African American woman City Manager in the United States. As a veteran senior government and nonprofit executive, Kimberly has used her voice to impact policy decisions while lobbying in New York City and on Capitol Hill. She now works within the social sector and leads Giving Blueprint, a consulting company with a mission to impact social change through the development of strategic partnerships and growth plans within the social sector.

CRITICAL CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RACE - Amber Sims

Amber currently serves as the Executive Director of Young Leaders Strong City, a nonprofit focused on youth development, leadership, and racial equity. She was formerly the Director of Regional Impact for Leadership for Educational Equity, an educational nonprofit focused on leadership pathways in civic engagement. Previously, Amber led workforce development at Workforce Solutions Greater Dallas Opportunity Center. Her theory of change was to emphasize the connection between education, workforce, and dual generation impact.

Other guests have included:

- Dallas Maverick CEO and President Cynt Marshall

- Leah Frazier , 2-Time Emmy Award-Winning and 10-Time ADDY Award-Winning entrepreneur

- Paula Stone Williams, internationally known speaker on issues of gender equity, LGBTQ advocacy, and religious tolerance

- Rafia Zakaria, author of Against White Feminism (W.W. Norton, 2021) and Veil (Bloomsbury, 2017) and a writer for the Guardian, Boston Review, The New Republic, The New York Times Book Review and Al Jazeera America

- Gretchen Bauer, Luxury handbag manufacturer

Find all The Tapestry episodes HERE

Dr. Froswa’ Booker-Drew is a Partnership Broker. Relational Leadership Junkie. Connector. Author/Speaker/Trainer. Co-Founder, HERitage Giving Circle. Currently, the Vice President of Community Affairs of the State Fair of Texas, she has been quoted and profiled in Forbes, Ozy, Bustle, Huffington Post and other media outlets around the world. In addition, she has been asked to speak on a variety of topics such as social capital and networking, leadership, diversity, and community development to national and international audiences. This included serving as a workshop presenter at the United Nations in 2013 on the Access to Power.

featured image found HERE

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Businesses without Bosses: from hard-nosed leadership to sustainable, self-managing systems

As many of you know, I’m very passionate about helping people understand and experiment with self-organizing.

Joella Bruckshaw and Julian Saipe are executive coaches who have a wonderful podcast series called ‘Behind The Screen’ where they share leadership insights with high profile leaders. In this series of impromptu discussions, Joella and Julian, along with their invited guests, discuss success, the characteristics we choose to reveal, and those we choose to keep behind the screen - engaging thoughts on leadership, performance, authenticity and having fun.

In Episode 12 of the podcast series, Joella and Julian talked with me about Self-Organization.

Our conversation explored how “businesses without bosses” can thrive, just as nature’s own eco-systems do. We also discussed how coaching could facilitate a transition from hard-nosed leadership to sustainable, self-managing systems, where purposefulness itself is the outcome.

Access the interview on Behind the Screen podcast at: iTunes/Apple HERE & Amazon Music HERE

June Holley has been weaving networks, helping others weave networks and writing about networks for over 40 years. She is currently increasing her capacity to capture learning and innovations from the field and sharing what she discovers through blog posts, occasional virtual sessions and a forthcoming book.

featured image found HERE

Understanding Movements

What follows is an excerpt from the Understanding Movements report, researched by Kapil Dawda, commissioned by Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies. You can access the full report and the accompanying Understanding Movements deck at the bottom of this post.

A movement in its simplest form is an act or process of moving. For example, an object moving from point A to point B embodies a movement.

In the context of social change, there are multiple ways to move from point A to point B. The most commonly encountered approach in the modern world is a programmatic one. It is employed by social and private sector organisations and governments through scale programs, like the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan. There are also collective-impact-based approaches, which have a more distributed and networked way of approaching change. Lastly, there are movements, a particular kind of collective impact.

In the context of social change, a movement has:

- A diverse collective of people and organisations coming together as participants

- The shared intention to create wide-scale, transformational change focused on a social, economic, environmental, or political problem that guides the collective direction

- Distributed, shared and bottom-up action by multiple participants, including those at the grassroots

Many famous movements emerged in the face of pressing crises. Some examples are the

Quit India Movement or Civil Rights Movement of the past and contemporary movements like the Arab Spring or #MeToo. However, movements are not limited to those that arise in response to a crisis that escalates through triggering incidents. Many others address latent, not urgent problems by applying the same principles. For example, Service Space is a global movement to unleash the innate spirit of generosity in people. YouthXYouth is another example of a worldwide movement focused on bringing back the agency of young people in their learning experience!

Movements are more than collective, confrontational action against oppressors in power. This view over-simplifies the complexity and leads us to think in terms of just bilateral dynamics. Many lasting movements take a more systemic view. To view movements more holistically, we must observe the relationships between the leaders, the participants, the organisations and the stakeholder groups involved. It is also worth examining who the leaders are, what they do, how they lead and most importantly, why they do it. It enables us to appreciate how movements work with a diverse collective to bring social, environmental or political change.

In their book New Power, Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms define New Power as “a current. It is made by many. It is open, participatory, and peer-driven. It uploads, and it distributes. Like water or electricity, it is most forceful when it surges. The goal of ‘new power’ is not to hoard but to channel.” By this definition, movements are a form of new power focused on bringing societal change.

Access the Understanding Movements Report and Presentation Deck HERE at NetworkWeaver and HERE at Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

This resource explores:

- What are movements?

- What is their relevance in social change?

- What are some of their defining features?

- How do they differ from programs or collective impact?

Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies (RNP) supports ideas, individuals and institutions doing ground-breaking work that enables a strong samaaj (society). The areas of work constitute a wide range spanning Access to Justice to Water. RNP has identified Active Citizenship, Climate and Biodiversity and Young Men and Boys as priorities.

Kapil Dawda is the Co-Initiator of the Wellbeing Movement, a Team Member at Viridus Social Impact Solutions and an active member of the Weaving Lab and Presencing communities. He is keen on tapping into the power of many to enable everyone, especially youth and children, to lead thriving lives

Originally published at Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

by Kapil Dawda, commissioned by Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

The Web of Change

Creating Impact Through Networks

The following post is excerpted from the introduction of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change, now available in print, as an audiobook, and as an ebook.

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

— Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Since the beginning of our species, humans have formed networks. Our social networks grow whenever we introduce our friends to each other, when we move to a new town, or when we congregate around a shared set of beliefs. Social networks have shaped the course of history. Historian Niall Ferguson has noted that many of the biggest changes in history were catalyzed by networks—in part, because networks have been shown to be more creative and adaptable than hierarchical systems.[1]

Ferguson goes on to assert that “the problem is that networks are not easily directed towards a common objective. . . . Networks may be spontaneously creative but they are not strategic.”[2] This is where we disagree. While networks are not inherently strategic, they can be designed to be strategic.

When deliberately cultivated, networks can forge connections across divides, spread information and learning, and spark collaborative action. As a result, they can “address sprawling issues in ways that no individual organization can, working toward innovative solutions that are able to scale,” write Anna Muoio and Kaitlin Terry Canver of Monitor Institute by Deloitte.[3] Networks can be powerful vehicles for creating change.

Of course, networks can have positive as well as negative effects. Economic inequality and the advantages and disadvantages of social class, race, ethnicity, gender, and other aspects of individual identity are in large part the result of network effects: certain types of people form bonds that increase their social capital, typically at significant social expense to those in other groups. Much of the world has become acutely aware of the harmful network effects arising from social media and the internet. This includes the proliferation of online echo chambers that feed people what they want to hear, even when it means rapidly spreading misinformation.

In our globally connected and interdependent society, it is imperative that we understand the network dynamics that influence our lives so that we can create new networks to foster a more resilient and equitable world. The choice in front of us is clear: either we can let networks form according to existing social, political, and economic patterns, which will likely leave us with more of the same inequities and destructive behaviors, or we can deliberately and strategically catalyze new networks to transform the systems in which we live and work.

A case in point is the RE-AMP Network, a collection of more than 140 organizations and foundations working across sectors to equitably eliminate greenhouse gas emissions across nine mid- western states by 2050. From the time it was formed in 2015, RE-AMP has helped retire more than 150 coal plants, implement rigorous renewable energy and transportation standards, and re-grant over $25 million to support strategic climate action in the Midwest. RE-AMP’s work is necessary in part because other powerful networks are also at play to maintain the status quo or to enrich the forces that profit from pollution and inequality.

We can look to the field of education for another example of a network creating significant impact. 100Kin10 is a massive collaborative effort that is bringing together more than three hundred academic institutions, nonprofits, foundations, businesses, and government agencies to train and support one hundred thousand science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) teachers across the United States in ten years. Founded in 2011, 100Kin10 is well on track to achieve its ambitious goal and has expanded its aim to take on the longer-term systemic challenges in STEM education.

The Justice in Motion Defender Network is a collection of human rights defenders and organizations in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua that have joined together to help migrants quickly obtain legal assistance across borders. Throughout the ongoing family separation crisis created by US immigration policies during the Trump administration, this network has been essential in locating deported parents in remote regions of Central America and coordinating reunification with their children.

Or consider a network whose impact spans the globe, the Clean Electronics Production Network (CEPN). CEPN brings together many of the world’s top technology suppliers and brands with labor and environmental advocates, governments, and other leading experts to move toward elimination of workers’ exposure to toxic chemicals in electronics production. Since forming in 2016, the network has defined shared commitments, developed tools and resources for reducing workers’ exposure to toxic chemicals, and standardized the process of collecting data on chemical use.

Networks like RE-AMP, 100Kin10, the Defender Network, and CEPN—along with many others you will learn about in this book—were not spontaneous or accidental; rather, they were formed with clear intent. These networks deliberately connect people and organizations together to promote learning and action on an issue of common concern. We call them impact networks to highlight their intentional design and purposeful focus, and to contrast them with the organic networks formed as part of our social lives.[4]

We think of impact networks as a combination of a vibrant community and a healthy organization. At the core they are relational, yet they are also structured. They are creative, and they are also strategic. Impact networks build on the life force of community—shared principles, resilience, self-organization, and trust— while leveraging the advantages of an effective organization, including a common aim, an operational backbone, and a bias for action. Through this unique blend of qualities, impact networks increase the flow of information, reduce waste, and align strategies across entire systems—all while liberating the energy of multiple actors operating at a variety of scales.

All around the world, impact networks are being cultivated to address complex issues in the fields of health care, education, science, technology, the environment, economic justice, the arts, human rights, and others. They mark an evolution in the way humans are organizing to create meaningful change.

To learn more about what impact networks are, how they work, and what it takes to cultivate and sustain them, check out the new book Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change.

[1]: Niall Ferguson, The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power (London: Penguin Books, 2018), xix.

[2]: Ferguson, The Square and the Tower, 43.

[3]: Anna Muoio and Kaitlin Terry Canver, Shifting a System, Monitor Institute by Deloitte, accessed December 17, 2020, https://www2.deloitte.com /content/dam/insights/us/articles/5139_shifting-a-system/DI_ Reimagining-learning.pdf.

[4]: June Holley has called them “intentional networks” in Network Weaver Handbook: A Guide to Transformational Networks (Athens, Ohio: Network Weaver Publishing, 2012). Peter Plastrik, Madeleine Taylor, and John Cleveland have called them “generative social impact networks” in Connecting to Change the World: Harnessing the Power of Networks for Social Impact (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2014).

Originally published at Converge

David Ehrlichman is a catalyst and coordinator of Converge and author of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change. With his colleagues, he has supported the development of dozens of impact networks in a variety of fields, and has worked as a network coordinator for the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network, Sterling Network NYC, and the Fresno New Leadership Network. He speaks and writes frequently on networks, finds serenity in music, and is completely mesmerized by his newborn daughter.ehrlichman@converge.net

How to build your network skills and approaches

Collective Mind is on a mission – to equip network leaders and managers with the skills and approaches to make their networks effective and impactful.

We exist because we believe in the power of networks to foster collective action, especially in support of systems change and addressing hard, complex problems. We also know from our firsthand experience that operating within a network environment requires different strategies, approaches, skills, and tools than those we use in more traditional organizations.

In our discussions with network leaders and managers, they’ve told us that they seek support, connections, and tools. Previous research told us that network managers don’t always come to their roles with network experience and that limited professional development opportunities exist to improve understanding and build skills.

Our goal is to fill these gaps by creating learning opportunities for network practitioners to improve their practice.

Collective Mind’s Virtual Summer Camp is a major opportunity to build your skills and approaches, with thoughtful, comprehensive frameworks to understand networks, access to experts and in-depth discussions on network topics, and peer connections through learning circles and networking opportunities.

Virtual Summer Camp runs over three weeks starting July 12th. The schedule is designed to accommodate busy schedules and workloads, and campers can choose to join the first two core weeks or all three weeks. Building on the experience of our inaugural camp in 2020, this year’s camp promises to be an incredible opportunity for participants to learn, connect, and improve their practice.

Collective Mind seeks to build the efficiency, effectiveness, and impact of networks and the people who work for and with them. We believe that the way to solve the world’s most complex problems is through collective action – and that networks, in the ways that they organize people and organizations around a shared purpose, are the fit-for-purpose organizational model to harness resources, views, strengths, and assets to achieve that shared purpose.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Leadership and Community in a Time of Transition

In communal transformation, leadership is about intention, convening, valuing relatedness, and presenting choices. It is not a personality characteristic or a matter of style, and therefore it requires nothing more than what all of us already have. This means we can stop looking for leadership as though it were scarce or lost, or it had to be trained into us by experts. If our traditional form of leadership has been studied for so long, written about with such admiration, defined by so many, worshipped by so few, and the cause of so much disappointment, maybe doing more of all that is not productive. The search for great leadership is a prime example of how we too often take something that does not work and try harder at it.

Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging

As a white man born into a well-off and well-educated family in the US, the idea that I might step into leadership was part of my conditioning. And as someone who has chosen work that involves issues of justice, equity, and inclusion, I find myself challenged to re-evaluate the very definition of leadership. In this, I have found two books to be particularly helpful. Reading Peter Block’s Community: The Structure of Belonging in 2010, I was struck by his declaration that “leadership is convening,” and by the concrete guidance he provides for living into that story. Some years later, I was further inspired by Frederic Laloux’s description in Reinventing Organizations of a new paradigm for governance, his addressing of questions related to hierarchies and self-organizing, and his vision for what might be possible as we continue to evolve our capacities for new forms of organizing. Both authors start from the premise that our conception of leadership in the dominant Western culture is failing us, opening the way to new approaches based on “power with” rather than “power over.”

I was brought up within that dominant culture as one of its most privileged members, and was taught to excel in things like critical analysis and debate. Then in 2010, I found myself called into work inspired by a new possibility that I suddenly recognized: we could make powerful use of our new virtual capacities to convene large groups of people by engaging them in generative dialogue about systemic transformation. I found that my old training did not serve me and was in fact a handicap in many respects. At the same time, I discovered that I had gifts for creating and holding hospitable space, listening deeply, and making meaning out of the diversity of opinions, beliefs, and worldviews that were being expressed in the conversations I helped convene. Block’s work offered both a powerful validation of this new direction and a road map for the journey.

Around the same time that I was reading Community, I had the delightful experience of shifting my story about myself. I had worked with a professional career consultant a few years earlier and had tested as an introvert (INFJ) on the Myers-Briggs personality inventory. Then one day while driving home and mentally preparing for a World Cafe conversation I was about to host online, it struck me that the excited energy I was feeling was characteristic of extroverts. So I immediately called my friend David, a Myers-Briggs maven, and asked him to look up the characteristics of the ENFJ personality. The answer? That people like me are leaders of groups, and that others are drawn to participate in those groups not because of efforts we make to persuade them that they should do so, but simply because of the way we show up. In Block’s words, this is “invitation as a way of being,” where the artist replaces the economist/salesman.

As I reflected on why I might have scored as an introvert, it occurred to me that I had exiled my gifts as a convener of hospitable space. My explanation for having done so was that, throughout my early adulthood, my efforts to show up as a whole person were not well received. So I told myself the story that I preferred my own company and a small set of close relationships, and that being in groups was a challenge for me because of my nature. Accordingly I made my professional world a small one, holding back on what I felt called to most deeply. Reflecting on this anew, it occurred to me that I had intuitively sensed the bankruptcy of the dominant paradigms through which I had been told I was supposed to engage with the world, and that the painful experiences in my work were the result of my rebellion against operating in that context. The discovery of this new way of showing up--as a convener of groups, in service to movements for transformational change-- was utterly liberating.

The other inspiration I drew from Block was the idea that community is required for transformation. It is not enough for us to work on ourselves in isolation. As Thich Nhat Hanh has famously said, “the next Buddha may be a sangha.” And so I embraced the creation of community as a core purpose of my work. I came to see the emergence of social fabric made up of many interwoven relationships as being the most important outcome in any engagement, over and above the conversational content or action planning that often provides the explicit context for a gathering.

The places where we live are failing to provide a strong sense of community for many of us. Other traditional markers such as nationality, ethnicity, gender, political ideologies, extended family structures, etc. also often do not seem sufficient or lack resonance. As a result, we are witnessing the increasing fragmentation of identity, accompanied by a yearning for belonging and connection to replace what we have lost. The dangers of this phenomenon are apparent all around us, most prominently in the political realm, as a product of the broader challenge of simply identifying a shared reality. As we all struggle with the fact that conventional wisdom has shown itself to be incomplete, flawed, and sometimes false, many are choosing to embrace conspiracy theories--a phenomenon that I believe to be toxic. Yet I also see a great opportunity in this unraveling--a chance for humanity to go through a kind of reweaving (or re-wilding) that builds upon what was good and important about our previous stories and forms of identity, yet also transcends the limits they carried with them.

As we co-create new forms of community, we get to try out identities that connect us directly to our gifts. Anthropologists have determined that the natural size for a tribal unit is a little less than 160 people, and that the “gift economy” was the original form of organization that we employed in such groups. I love to imagine what a group that size can do today with the power of our new technologies, if it succeeds in fully bringing forth the gifts of its members and releasing them into the world. And what might be possible if these “tribal groups” learned to connect and collaborate with one another, based on natural alignments in purpose and values? And then what if we learned to do this in a way that reconnected us to the earth as a whole, by linking together our care for each of the places where our feet touch the ground?

This vision of transformational communities requires a good deal of coordination, collaboration, and co-creation both within and among groups. So it is not surprising that the crucial need for wise and effective governance has emerged in my work time and time again. Tom Atlee, my first mentor in the convening work I began in 2010, introduced me to the concept of collective intelligence and to a wide variety of processes that have been developed for tapping into it, including many that relate to governance and decision-making. His new Wise Democracy Pattern Language is a wonderful resource, as is the Co-intelligence Institute website he curates.

The need for governance structures became more tangible for me when I co-launched Occupy Cafe and was exposed to consensus decision-making and Sociocracy. Not long after that, I became part of the core team for the Great Work Cultures initiative and was also introduced to the Future of Work movement, both of which focused on new paradigm approaches to decision-making and sharing power in the workplace. Another influence was the concept from The Circle Way of “a leader in every chair.” And the related idea that movements need to be “leaderful” rather than “leaderless” came from Peggy Holman, whose book Engaging Emergence also taught me practical and inspiring approaches to convening. Then in 2014 I read Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations, which seemed to pull it all together.

Like Block, Laloux presents models for organizing ourselves using “power with” rather than “power over.” In his synthesis based on the study of a wide variety of organizations, he identifies three key innovations: evolutionary purpose, self-organizing, and the welcoming of our whole selves into the spaces where we work. He gives examples of each of these patterns happening in a number of organizations, while also stating that he has yet to see any instance where all three are present in a single one. Since he wrote his book, many people--myself included-- have been inspired by his observations (and those of the many others working on similar visions of “next stage” organizations) to attempt to co-create initiatives that have all three of these elements in their DNA.

One of the interesting patterns I've observed in groups that take up this challenge has to do with hierarchies. Because our old models have failed us so dramatically in so many respects, there is now a deep mistrust of leadership. And because so many voices have been marginalized for so long, there is a need for them to now be heard. How we learn from these experiences in order to create spaces where we thrive can be a tricky thing.

I remember vividly my visit to the Occupy Wall Street encampment in New York City in 2011. I was particularly struck by the general assembly I witnessed that day. There was a problem to deal with: a giant pile of dirty, wet laundry had accumulated as a result of several days of rain. It was beginning to mildew. Someone had already secured a truck and located a laundromat uptown that would welcome them. All that remained was for the group to decide to allocate money for the laundry machines. There were easily 150 people participating in that deliberation. It took over an hour (using the famed “people’s mic”) to hear everyone who wished to speak and to decide that yes, the money should be released so that the laundry could get done. While many might have seen this as something less than good governance, I chose to interpret it as a kind of communal poetry!

It is crucial that we create spaces for collective expression that allow all voices to be heard. Peter Block gives us one model for doing so in a way that weaves community and brings forth our gifts. His approach creates a context of relatedness, trust, commitment, and the safety to dissent. These are crucial precursors to sharing power well, but we also need structures and processes designed to support us in making decisions together in a good way. A key pattern for doing this, as Laloux found in his research, is the empowerment of small groups closest to the work that needs to be done as the vehicle through which authority is allocated. As Block also declares: “the small group is the unit of transformation.”

When needed, small groups can seek input from the whole community or organization, and can also reach out beyond it to all stakeholders, if desired. We have lots of great methods for this kind of "advice process," not to mention talented facilitators who love this kind of work. But it still makes sense in most cases for a small group--people connected to the needs being addressed and the consequences of their choices-- to process that broader input, make an appropriate decision, and then stay engaged and agile in order to respond to what happens as a result. Sociocracy works in this way, and I am very drawn to that methodology, although a full implementation of all its elements may not be the right answer in many cases. Indeed, I don't believe there is a one-size-fits-all solution, and I think that we are still very much in the beginning stages of figuring out how to do this well. This is especially true to the extent that we wish to transcend the organization as the core unit through which work must be done, returning to communities as the way to meet many more (and perhaps even most) of our needs.

The context in which these questions about leadership and community have the most meaning for me is the possibility of near-term civilizational collapse. Though Jem Bendell has become perhaps its most prominent voice today, Meg Wheatley was the thought leader I first paid attention to who was preaching this gospel. After many years of working to support the emergence of a new paradigm for humanity based on the idea that “whatever the problem, community is the answer,” Wheatley had a change of heart, giving up on the idea that we could still “save the world.” In her 2012 book So Far from Home and the subsequent Who Do We Choose to Be? she painted a stark picture of despair among many who, like her, had worked for decades to bring forth a world that works for all beings. Now she spoke instead of the need for leaders to create “islands of sanity” amidst the sea of collapse.

Is Wheatley right? Joanna Macy, the contemporary of hers who popularized the term “the Great Turning” to encompass the magnitude of the civilizational shift they and others were imagining, says that we still don't know whether it is too late for us to midwife that better world or not. I find her view to be compelling as well. This brings me back to Block, who emphasizes that the story we choose to tell ourselves is just that: a story and a choice. And that the choice we make has payoffs and costs.

And so I will close with a story I choose to tell myself. Holding onto it gives me the payoff of validating the community weaving work I feel called to do, and my sense of having found a good way to be a leader. It therefore helps me to minimize the guilt I hold onto for living a privileged life, including not doing more to dismantle the systems of oppression I benefit from, and choosing to have an environmental footprint that is way bigger than my personal fair share.

What are some of the costs of my attachment to the story? One is that I may not be paying attention to other possibilities for making use of my gifts. Another is that my sense of self worth and identity is dependent on outcomes I often cannot see and must take on faith. A third might be that I have fooled myself into believing that I am practicing “power with” when in fact I am perpetuating the old patterns of “power over.” Furthermore, this story leaves me open to the criticism that I am a “virtue signalling” hypocrite because, while I claim to be a stand for the need to transform our ways of doing things so that we reweave rather than unravel our environmental, social, and spiritual life support systems, I am choosing a life of privilege that contributes to that very unraveling.

For now, knowing all that, I am sticking with the story...

There may not be much difference between the work of creating islands of sanity and of reweaving the whole world. It might “simply” be a matter of tens of thousands of transformationally empowered communities, each doing powerful work in their own local domains (be they place-based or virtual) while also supporting one another to bring forth a global shift. For all we know, just as the mycelial mat is hidden from our view and has only recently come to define our basic understanding of how a forest works, a sufficiently dense weaving of relationships, flows of information and resources, and connections to other parts of the transformational ecosystem might already be underway such that tens of thousands of these communities are springing up around the globe, mushroom-like, in order to nourish us, transform our collective consciousness, and cast billions of potent spores to the winds of change.

*Published in the Sharing Corn Journal, Volume 2, available from Joy Generation in print form here and in digital form via Amazon here.

featured image found at WSJ.com

Ben Roberts is a systemic change agent and“process artist,” working in service to what Joanna Macy and others have called "The Great Turning." Inspired since 2010 by the internet’s largely untapped power to convene and support new modalities for participatory dialogue, he has been a pioneer in bringing large group conversational processes into the virtual realm via platforms such as Zoom and Slack, and in blending and creating synergies between virtual and in-person engagement.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Funding Successful Collaborations

Professor Wei-Skillern’s decade of research on successful nonprofit collaborations highlights key success factors that closely align with the behavioral changes required for collective impact initiatives to succeed.

In studying successful nonprofit networks, I have found that there are four key operating principles that are critical to collaboration success. These soft skills are the ‘secret sauce’ that differentiates mediocre collaborations from those that achieve transformational change. Surprisingly, the operating principles of funders who have successfully supported networks differ dramatically from common practice in the philanthropic sector.

- Mission not Organization – The Energy Foundation was founded in 1991 as a collaboration among Rockefeller, Pew and McArthur Foundations. With a $100 million commitment over 10 years, the founding donors provided patient capital, agreed that EF should be governed by an expert board rather than large donors, and encouraged the founding executives to be entrepreneurial and let the work of the foundation speak for itself (and to other potential donors) rather than get caught up in building the organization’s infrastructure. Their foresight enabled EF to catalyze the growth of energy philanthropy such that billions are now being committed to the field worldwide, though EF’s own budget has remained relatively modest, amounting to $100 million annually. EF’s goal has always been leveraged impact, not organizational scale. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Trust not Control - EF makes grants to regional groups that carry out energy policy work, then helps them coordinate so they can learn and adapt. Sometimes, EF grants to coalitions of nonprofits which are then able to regrant the funding according to how the local nonprofit leaders think the resources can best be utilized across the coalition. EF president, Eric Heitz describes the foundation’s operating philosophy as ‘service to the field.’ He notes, “We believe that people who are closer to the challenges are often in a better position to make the strategic call.” This is the ultimate in unrestricted funding--allowing the grantee full flexibility to use the funds not only internally, but also through its peers.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]