A Journey Toward Becoming an Anti-Racist and Multicultural Organization

A note from the editor: This post is a letter sent on April 16th from The Wallace Center at Winrock International to it's friends and colleagues. Network Weaver asked to republish this letter, and the accompanying resource, because, like The Wallace Center, we also see the potential for transformational impact in sharing a story of awakening to organizational inequity and enacting systematic change. The authors write: "By sharing our own story, we might encourage others to interrogate their own blind spots, rebuild new systems and processes that prioritize equity, and shift organizational cultures"

A couple of years ago, our team at the Wallace Center undertook an honest assessment of our organization’s history, values, culture, operations, and programs to determine where we landed on the Continuum on Becoming an Anti-Racist Multicultural Organization. What we realized and learned through that reflection was painful and real, but it marked the beginning of our continuous efforts to learn, grow, and center racial equity in our organization and work.

In the spirit of accountability, vulnerability, and transparency, we want to share the Wallace Center’s Journey Toward Becoming an Anti-Racist and Multicultural Organization.

Unfortunately, the timing of this message coincides with the continued brutality against Black and Brown people at the hands of the police. This week's news reports out of Minneapolis about Daunte Wright's murder and Derek Chauvin's ongoing trial demonstrate the urgency for systems change. We will never achieve economic, environmental, and social justice without first achieving racial justice.

Learning from our past.

For decades, the Wallace Center didn’t acknowledge or address the historic and current racism that underpins our farming and food systems. We sat on the sidelines, and our passivity and complacency reinforced racism and racial inequity in the food system and in the movement to change it. Partners and funders substantiated this hard truth; that we as an organization had a lot of work to do to meaningfully center racial justice and equity in our food systems change work and dismantle white supremacy culture within our team and parent organization, Winrock International.

That reflection marked a turning point for our team. Since 2017 we have been in process to put our intentions of being a racially-just organization into practice. This has been and continues to be both a personal and organizational journey for our staff. As a predominantly white team within a predominantly white organization – historically and today – we undertake this work with a sense of humility and from a position of learning rather than knowing. Institutional inequity and white supremacy is deeply entrenched in our organizational structures and systems and is pervasive in the domestic non-profit field as well as the international development sector we are embedded within at Winrock International. This includes not only our own organization, but also those with whom we affiliate, including those who fund our work.

Moving forward, together.

This document provides a summary of our journey thus far towards centering racial justice and equity in our organization in a meaningful, authentic, and accountable way as embodied in our racial equity commitments. There are many resources linked throughout the document that have been instrumental in fueling our internal work and we hope this will be helpful for others. It is not a “how-to” guide – we are not experts in advancing racial equity in organizations – but rather a perspective of how we’re taking steps to undo racism in our organization. One such example is through the Food Systems Leadership Network’s Network Weavers conversations, in which members virtually connected to discuss ways in which our work could contribute to and advance systems change.

We can’t do this work alone.

Our learning journey has been encouraged and supported by the work of other organizations and leaders who have inspired and challenged us. We have kept much of our process and learning internal to the Wallace Center and our parent organization, Winrock International, which has more recently started the work towards equity. It is our work to do. After the killing of George Floyd last year, followed by the international uprising against institutional and structural racism, we felt that our Wallace Center journey could be a helpful reference for Winrock International and other (mostly white-led) organizations who are reckoning with their own complicity in perpetuating white supremacy and racism. By sharing our own story, we might encourage others to interrogate their own blind spots, rebuild new systems and processes that prioritize equity, and shift organizational cultures. We also agreed that sharing our journey and our commitments publicly would enable others to hold us accountable as we work towards becoming an authentic and explicitly anti-racist organization.

We want to specifically thank The Justice Collective for their partnership and support of our team, and honor the hard work and commitment of each staff member at the Wallace Center who has contributed to our evolution. We are still very much in the thick of it – the journey toward our collective liberation has no endpoint – and invite your feedback, reflections, and questions.

In solidarity,

Susan Schempf and Pete Huff, Co-Directors, Wallace Center

The Wallace Center develops partnerships, pilots new ideas, and advances solutions to strengthen communities through resilient farming and food systems. We serve the growing community of organizations, businesses, and public agencies involved in building a good farming and food system in the United States. Our program work focuses on advancing collaborative, regional efforts to grow and move good food – food that is healthy, regeneratively produced, and recognizes and builds value across the entire supply chain, from producers to farm workers, aggregators, processors, distributors, buyers, and the community based organizations supporting the food ecosystem.

featured image found HERE

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

by Susan Schempf and Pete Huff, Co-Directors, Wallace Center

Leadership and Community in a Time of Transition

In communal transformation, leadership is about intention, convening, valuing relatedness, and presenting choices. It is not a personality characteristic or a matter of style, and therefore it requires nothing more than what all of us already have. This means we can stop looking for leadership as though it were scarce or lost, or it had to be trained into us by experts. If our traditional form of leadership has been studied for so long, written about with such admiration, defined by so many, worshipped by so few, and the cause of so much disappointment, maybe doing more of all that is not productive. The search for great leadership is a prime example of how we too often take something that does not work and try harder at it.

Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging

As a white man born into a well-off and well-educated family in the US, the idea that I might step into leadership was part of my conditioning. And as someone who has chosen work that involves issues of justice, equity, and inclusion, I find myself challenged to re-evaluate the very definition of leadership. In this, I have found two books to be particularly helpful. Reading Peter Block’s Community: The Structure of Belonging in 2010, I was struck by his declaration that “leadership is convening,” and by the concrete guidance he provides for living into that story. Some years later, I was further inspired by Frederic Laloux’s description in Reinventing Organizations of a new paradigm for governance, his addressing of questions related to hierarchies and self-organizing, and his vision for what might be possible as we continue to evolve our capacities for new forms of organizing. Both authors start from the premise that our conception of leadership in the dominant Western culture is failing us, opening the way to new approaches based on “power with” rather than “power over.”

I was brought up within that dominant culture as one of its most privileged members, and was taught to excel in things like critical analysis and debate. Then in 2010, I found myself called into work inspired by a new possibility that I suddenly recognized: we could make powerful use of our new virtual capacities to convene large groups of people by engaging them in generative dialogue about systemic transformation. I found that my old training did not serve me and was in fact a handicap in many respects. At the same time, I discovered that I had gifts for creating and holding hospitable space, listening deeply, and making meaning out of the diversity of opinions, beliefs, and worldviews that were being expressed in the conversations I helped convene. Block’s work offered both a powerful validation of this new direction and a road map for the journey.

Around the same time that I was reading Community, I had the delightful experience of shifting my story about myself. I had worked with a professional career consultant a few years earlier and had tested as an introvert (INFJ) on the Myers-Briggs personality inventory. Then one day while driving home and mentally preparing for a World Cafe conversation I was about to host online, it struck me that the excited energy I was feeling was characteristic of extroverts. So I immediately called my friend David, a Myers-Briggs maven, and asked him to look up the characteristics of the ENFJ personality. The answer? That people like me are leaders of groups, and that others are drawn to participate in those groups not because of efforts we make to persuade them that they should do so, but simply because of the way we show up. In Block’s words, this is “invitation as a way of being,” where the artist replaces the economist/salesman.

As I reflected on why I might have scored as an introvert, it occurred to me that I had exiled my gifts as a convener of hospitable space. My explanation for having done so was that, throughout my early adulthood, my efforts to show up as a whole person were not well received. So I told myself the story that I preferred my own company and a small set of close relationships, and that being in groups was a challenge for me because of my nature. Accordingly I made my professional world a small one, holding back on what I felt called to most deeply. Reflecting on this anew, it occurred to me that I had intuitively sensed the bankruptcy of the dominant paradigms through which I had been told I was supposed to engage with the world, and that the painful experiences in my work were the result of my rebellion against operating in that context. The discovery of this new way of showing up--as a convener of groups, in service to movements for transformational change-- was utterly liberating.

The other inspiration I drew from Block was the idea that community is required for transformation. It is not enough for us to work on ourselves in isolation. As Thich Nhat Hanh has famously said, “the next Buddha may be a sangha.” And so I embraced the creation of community as a core purpose of my work. I came to see the emergence of social fabric made up of many interwoven relationships as being the most important outcome in any engagement, over and above the conversational content or action planning that often provides the explicit context for a gathering.

The places where we live are failing to provide a strong sense of community for many of us. Other traditional markers such as nationality, ethnicity, gender, political ideologies, extended family structures, etc. also often do not seem sufficient or lack resonance. As a result, we are witnessing the increasing fragmentation of identity, accompanied by a yearning for belonging and connection to replace what we have lost. The dangers of this phenomenon are apparent all around us, most prominently in the political realm, as a product of the broader challenge of simply identifying a shared reality. As we all struggle with the fact that conventional wisdom has shown itself to be incomplete, flawed, and sometimes false, many are choosing to embrace conspiracy theories--a phenomenon that I believe to be toxic. Yet I also see a great opportunity in this unraveling--a chance for humanity to go through a kind of reweaving (or re-wilding) that builds upon what was good and important about our previous stories and forms of identity, yet also transcends the limits they carried with them.

As we co-create new forms of community, we get to try out identities that connect us directly to our gifts. Anthropologists have determined that the natural size for a tribal unit is a little less than 160 people, and that the “gift economy” was the original form of organization that we employed in such groups. I love to imagine what a group that size can do today with the power of our new technologies, if it succeeds in fully bringing forth the gifts of its members and releasing them into the world. And what might be possible if these “tribal groups” learned to connect and collaborate with one another, based on natural alignments in purpose and values? And then what if we learned to do this in a way that reconnected us to the earth as a whole, by linking together our care for each of the places where our feet touch the ground?

This vision of transformational communities requires a good deal of coordination, collaboration, and co-creation both within and among groups. So it is not surprising that the crucial need for wise and effective governance has emerged in my work time and time again. Tom Atlee, my first mentor in the convening work I began in 2010, introduced me to the concept of collective intelligence and to a wide variety of processes that have been developed for tapping into it, including many that relate to governance and decision-making. His new Wise Democracy Pattern Language is a wonderful resource, as is the Co-intelligence Institute website he curates.

The need for governance structures became more tangible for me when I co-launched Occupy Cafe and was exposed to consensus decision-making and Sociocracy. Not long after that, I became part of the core team for the Great Work Cultures initiative and was also introduced to the Future of Work movement, both of which focused on new paradigm approaches to decision-making and sharing power in the workplace. Another influence was the concept from The Circle Way of “a leader in every chair.” And the related idea that movements need to be “leaderful” rather than “leaderless” came from Peggy Holman, whose book Engaging Emergence also taught me practical and inspiring approaches to convening. Then in 2014 I read Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations, which seemed to pull it all together.

Like Block, Laloux presents models for organizing ourselves using “power with” rather than “power over.” In his synthesis based on the study of a wide variety of organizations, he identifies three key innovations: evolutionary purpose, self-organizing, and the welcoming of our whole selves into the spaces where we work. He gives examples of each of these patterns happening in a number of organizations, while also stating that he has yet to see any instance where all three are present in a single one. Since he wrote his book, many people--myself included-- have been inspired by his observations (and those of the many others working on similar visions of “next stage” organizations) to attempt to co-create initiatives that have all three of these elements in their DNA.

One of the interesting patterns I've observed in groups that take up this challenge has to do with hierarchies. Because our old models have failed us so dramatically in so many respects, there is now a deep mistrust of leadership. And because so many voices have been marginalized for so long, there is a need for them to now be heard. How we learn from these experiences in order to create spaces where we thrive can be a tricky thing.

I remember vividly my visit to the Occupy Wall Street encampment in New York City in 2011. I was particularly struck by the general assembly I witnessed that day. There was a problem to deal with: a giant pile of dirty, wet laundry had accumulated as a result of several days of rain. It was beginning to mildew. Someone had already secured a truck and located a laundromat uptown that would welcome them. All that remained was for the group to decide to allocate money for the laundry machines. There were easily 150 people participating in that deliberation. It took over an hour (using the famed “people’s mic”) to hear everyone who wished to speak and to decide that yes, the money should be released so that the laundry could get done. While many might have seen this as something less than good governance, I chose to interpret it as a kind of communal poetry!

It is crucial that we create spaces for collective expression that allow all voices to be heard. Peter Block gives us one model for doing so in a way that weaves community and brings forth our gifts. His approach creates a context of relatedness, trust, commitment, and the safety to dissent. These are crucial precursors to sharing power well, but we also need structures and processes designed to support us in making decisions together in a good way. A key pattern for doing this, as Laloux found in his research, is the empowerment of small groups closest to the work that needs to be done as the vehicle through which authority is allocated. As Block also declares: “the small group is the unit of transformation.”

When needed, small groups can seek input from the whole community or organization, and can also reach out beyond it to all stakeholders, if desired. We have lots of great methods for this kind of "advice process," not to mention talented facilitators who love this kind of work. But it still makes sense in most cases for a small group--people connected to the needs being addressed and the consequences of their choices-- to process that broader input, make an appropriate decision, and then stay engaged and agile in order to respond to what happens as a result. Sociocracy works in this way, and I am very drawn to that methodology, although a full implementation of all its elements may not be the right answer in many cases. Indeed, I don't believe there is a one-size-fits-all solution, and I think that we are still very much in the beginning stages of figuring out how to do this well. This is especially true to the extent that we wish to transcend the organization as the core unit through which work must be done, returning to communities as the way to meet many more (and perhaps even most) of our needs.

The context in which these questions about leadership and community have the most meaning for me is the possibility of near-term civilizational collapse. Though Jem Bendell has become perhaps its most prominent voice today, Meg Wheatley was the thought leader I first paid attention to who was preaching this gospel. After many years of working to support the emergence of a new paradigm for humanity based on the idea that “whatever the problem, community is the answer,” Wheatley had a change of heart, giving up on the idea that we could still “save the world.” In her 2012 book So Far from Home and the subsequent Who Do We Choose to Be? she painted a stark picture of despair among many who, like her, had worked for decades to bring forth a world that works for all beings. Now she spoke instead of the need for leaders to create “islands of sanity” amidst the sea of collapse.

Is Wheatley right? Joanna Macy, the contemporary of hers who popularized the term “the Great Turning” to encompass the magnitude of the civilizational shift they and others were imagining, says that we still don't know whether it is too late for us to midwife that better world or not. I find her view to be compelling as well. This brings me back to Block, who emphasizes that the story we choose to tell ourselves is just that: a story and a choice. And that the choice we make has payoffs and costs.

And so I will close with a story I choose to tell myself. Holding onto it gives me the payoff of validating the community weaving work I feel called to do, and my sense of having found a good way to be a leader. It therefore helps me to minimize the guilt I hold onto for living a privileged life, including not doing more to dismantle the systems of oppression I benefit from, and choosing to have an environmental footprint that is way bigger than my personal fair share.

What are some of the costs of my attachment to the story? One is that I may not be paying attention to other possibilities for making use of my gifts. Another is that my sense of self worth and identity is dependent on outcomes I often cannot see and must take on faith. A third might be that I have fooled myself into believing that I am practicing “power with” when in fact I am perpetuating the old patterns of “power over.” Furthermore, this story leaves me open to the criticism that I am a “virtue signalling” hypocrite because, while I claim to be a stand for the need to transform our ways of doing things so that we reweave rather than unravel our environmental, social, and spiritual life support systems, I am choosing a life of privilege that contributes to that very unraveling.

For now, knowing all that, I am sticking with the story...

There may not be much difference between the work of creating islands of sanity and of reweaving the whole world. It might “simply” be a matter of tens of thousands of transformationally empowered communities, each doing powerful work in their own local domains (be they place-based or virtual) while also supporting one another to bring forth a global shift. For all we know, just as the mycelial mat is hidden from our view and has only recently come to define our basic understanding of how a forest works, a sufficiently dense weaving of relationships, flows of information and resources, and connections to other parts of the transformational ecosystem might already be underway such that tens of thousands of these communities are springing up around the globe, mushroom-like, in order to nourish us, transform our collective consciousness, and cast billions of potent spores to the winds of change.

*Published in the Sharing Corn Journal, Volume 2, available from Joy Generation in print form here and in digital form via Amazon here.

featured image found at WSJ.com

Ben Roberts is a systemic change agent and“process artist,” working in service to what Joanna Macy and others have called "The Great Turning." Inspired since 2010 by the internet’s largely untapped power to convene and support new modalities for participatory dialogue, he has been a pioneer in bringing large group conversational processes into the virtual realm via platforms such as Zoom and Slack, and in blending and creating synergies between virtual and in-person engagement.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

This is How #WeGovern

Last year, we witnessed the near collapse of our collective systems—the systems that should be sustaining us when we need them most.

And the truth is, they’ve been failing us for generations. Today, amid a global pandemic, sustained violence against Black lives, brazen attacks by white supremacists, climate catastrophe, and pervasive economic injustice--we can see what Black and Indigenous folx have been saying for generations: these systems were not designed for us.

It is time they were.

We Govern is a roadmap for that creation. This foundational set of agreements were written by a group of predominantly Black, Indigenous, people of color across the US, to guide how we make the decisions that impact all of us--including how we choose to live together, use our resources, and build systems rooted in radical care.

It is an invitation to redefine governance.

Governance is the process by which we determine the norms and rules that guide everyday life and behavior, and we—all of us—have a role in it. Whether it’s through our personal lives as parents, friends, neighbors, caregivers, and stewards; or in our work as leaders and decision-makers—the choices we make each day determine our emergent future.

As our FAQ page says, “Whether deciding if it is worth it to struggle with a kiddo to eat broccoli, facilitating a healing conversation among friends, or creating a spending plan for clean energy in your town, the act of making choices for our collective wellbeing is governance.”

Governance is about making decisions together—at small and large scales—about the things that matter to us and impact our lives.

Today, together, we envision a more just, harmonious, and thriving future that refuses to leave anyone behind. We envision a world where we tend to ourselves and each other knowing that the choices we make each day add up to the world we’re building. We imagine systems of radical care in keeping with our sacred responsibility to care for future generations and the earth we share. The world we want is rooted in mutual care, deep relationship, dignity, and safety — for ourselves, for each other, and for the natural world.

Now, in the early part of 2021, we find ourselves still deep in a pandemic, clambering to stabilize the harms of last year, as we continue moving toward a still uncertain future. In this moment, a vision of another world is more urgent — and more possible — than ever.

By planting the seeds of commitment to collective care, we can create the world we want through the choices we make. WeGovern is an invitation to align our actions with our values—to commit to the foundational agreements we need in order to carve a path toward what’s possible.

The world we want — a world where all beings can thrive — begins with each of us. And it can start now.

To be counted among those who are embracing the sacred responsibility to take action and care for our collective wellbeing, sign on here.

Access the WeGovern Media Toolkit HERE or visit WE-Govern.org directly.

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources? DONATE HERE to assist us in continuing the shared vision & collaborative campaign for equity, justice, & transformation.

Is Defunding Police Departments Right for Your City?

Is Defunding Police Departments Right for Your City?

Will it Lead to Sustainable Success or Catastrophic Failure?

People around the world are protesting against racism and police brutality. The system is breaking down (or in the throes of self-correction, depending on your point of view). One solution that has been suggested is to defund police departments. It is unclear, however, whether defunding is the best approach for all cities.

Arguments against defunding suggest that it will lead to greater racial inequality and harm to the community as poor neighborhoods organize around criminal gangs. Some fear that removing the devil we know will lead to the arrival of seven that we do not. A wide variety of arguments in favor of defunding range from the relatively simple to the relatively complex. Each of them is claiming that their plan will lead to greater social justice and less violence.

Despite the range of opinions, two things are certain. First, things cannot continue as they are. There must be change and the change must be substantial. Second, the path to change is not clear, there is a veritable cacophony of voices and opinions on which way we should go.

In this article we will briefly explore our chances for successful change based on our existing understanding of the situation. Then, we will suggest a process for moving forward at the local level with a few key points to keep in mind for maximizing our chances for successfully creating communities that are safe, prosperous, and just. The first question is “do we understand the situation?” The short answer is no.

How do we know how much we know?

One warning flag about our lack of knowledge may be found in the halls of academia. A search for scholarly papers on the topic of “defunding police” found only seven publications. Compare that result with a search for papers on “police brutality” which found nearly sixty thousand publications.

Do those thousands of publications provide us with an effective understanding of police brutality? Are we able to eliminate police brutality? Obviously not. So, how do we think that we can solve the more complex problem of defunding police to improve safety and justice in our communities? It seems we have a vast quantity of knowledge, without much quality or usefulness of knowledge.

Of course, the academic world is not the only repository of knowledge. There are several web sites and articles providing suggestions for finding justice by defunding police. These include “For a World Without Police” and “Transform Harm” with more articles published on other sites almost every day. Each is different with alternate suggestions for action ranging from reducing police use of military hardware, to disbanding police departments.

One case that is increasingly mentioned as an example of successful de-funding is Camden, New Jersey. In that situation, however, the police department was disbanded and then re-formed. There is no guarantee that Camden faced the exact same situation as your city or that the Camden solution will prove effective in your city.

While reasonable people might argue forever about the relative merits of the many plans and few examples of success, we cannot argue forever – justice should be swift. However, justice should also be sure. The question becomes, “How can we predict if a plan might work?”

Research in the science of conceptual systems provides a method for evaluating those plans according to their internal logic structures. Let’s look at one, reasonably simple, plan for defunding the police to provide an example of how the structure of our knowledge might be understood. From a recent article we create the following diagram:

Thanks for the free online mapping platform to: https://www.plectica.com

Here, there are seven boxes – each representing a concept that is relevant to the topic of defunding police departments. They are connected by arrows representing causal relationships. For example, the more community patrols in a neighborhood, the less need there will be for police (and, presumably, less violence and more justice for all).

We can measure the structure of this knowledge by first counting the number of “transformative” concepts (those have more than one arrow pointing in to them). Here, the only transformative concept is “Less need for police.” Next, we count the total number of concepts (seven). Then, divide the transformative by the total to get 0.14. Thus, we can say that this knowledge is 14% structured and so has about a 14% chance of success (assuming that each of those causal arrows is supported by good data from previous research).

There is nothing worse than a simple plan.

To have a better plan, representing more useful knowledge, with a better chance of success, we need a map that has more boxes and more connections.

More pragmatically, the structural weakness of this diagram can be seen starting with its “daisy petal” arrangement. Imagine each box is being run by a different organization. All of them competing for funding, each of them ready to take credit for success but point the finger of blame at the other five groups if the plan does not succeed. This arrangement almost guarantees that the many groups will be in conflict with each other instead of cooperating for common and interdependent goals. Because, working in their silos, they are not collaborating as an effective network should.

This kind of “daisy fail” can be avoided by following two parallel paths of developing more structured knowledge on one hand, and by using better tools of government on the other. Both of these require communication and collaboration.

The “tools of government” path means deploying the best approach to find success within each box. For example, to improve our mental healthcare system we might consider providing grants, contracting those services out, mobilizing community volunteers, or any one of many different approaches. The choice of which tool to apply will be based on the appropriateness of that tool to the specific community. That choice, of course, would be made by the careful consideration of a diverse stakeholders. That means reaching out to find an ever-expanding circle of stakeholders and litening carefully to their concerns, insights, and ideas.

The second path is to improve the structure (and so the usefulness) of our knowledge. Here, there are a few basic strategies. First, we want to integrate research from multiple fields of knowledge. As mentioned above, there are untold thousands of research papers available; what we need to do is synthesize them. The second strategy is to access and integrate knowledge from a diverse range of stakeholders (black, white, police, non-profits, government agencies, social workers – more diversity is better). The process of collaborative integration accelerates our shared learning.

While some may see that as a recipe for confusion, their many insights can be integrated effectively using a “practical mapping” approach that has proved effective in creating more structured knowledge. Looking back at the daisy diagram above, we want to understand how all of the boxes may be connected. If we do it right, each organization will be working to support the others; and, will be accountable to the others. In short, creating a collaborative action network.

These parallel paths to success are guided by ongoing research into the “structure of knowledge” that shows how we can develop policies and plans that are more likely to succeed. Also, increasingly researcher are newer “tools of government” that are providing new ways to deal with old problems. Together, these tools, and the knowledge for how they might best be applied in each local situation, suggest a path forward that is likely to have sustainable success.

Instead of advocating for “bandaid” approach devoid of real change, or a “defund the police today” approach of immediate action, we would suggest an approach that is likely to lead to successful change in less than a year as follows:

- Understanding the situation (local facilitators use the practical mapping approach to generate a shared understanding among diverse stakeholder groups and scholarly research).

- Identify where solutions have been found and adapt the appropriate tools for each locality (using the map from step #1, carefully consider the range of tools for each part of the situation and choose the best tool for action).

- Apply solutions in parallel with existing police work (using insights from steps one and two, begin implementing tools being sure to identify how actions of each part will support other parts).

- Evaluate and return to step #1 (this will include tracking measurable results and reporting them with full transparency through community meetings and online dashboards).

With competent leadership, the first two steps should require less than two months each to create an effective map and choose the best tools. With tools in hand and a shared plan, step three may begin almost immediately with activities easily coordinated based on the map. Results may require a few months to manifest; however, they certainly should require less than a year. Data collection will be ongoing. And, with that data, participants can revise the process as needed.

To summarize, we have a great quantity of knowledge but that knowledge is not have a high quality. It is unstructured and so provides only the pretense of understanding. Thus, as it stands, dramatic efforts to defund police have about an 86% chance of failing to reach their goals.

Likewise, it should also be noted, that with less structure and less chance of success also comes greater chance for unanticipated negative consequences. So, the concern about gaining seven devils we don’t know, just to get rid of one we do, seems quite reasonable.

This kind of failure has been seen before. Even policies that are well funded and broadly supported, such as the “war on drugs,” have failed to reach their goals. Worse, they have spawned a variety of new problems such as sending more people to prison which results in increased costs to taxpayers and the destruction of families.

Because action should be taken to advance justice for all, this post has outlined a path of collaborative communication and learning for toward improving knowledge for effective implementation that gives us the best chance for success within a reasonable time frame. The results may not lead to any one group being perfectly satisfied, but they will lead to better, safer, just, and prosperous communities for the benefit of all.

About the Author

Steven E. Wallis, PhD

Director, Foundation for the Advancement of Social Theory (FAST)

Capella University, School of Social and Behavioral Sciences

Researching and consulting on policy, theory, and strategic planning

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5207-603X

Dr. Wallis is a Fulbright alumnus, international visiting professor, award-wining scholar, and Director of the Foundation for the Advancement of Social Theory; researching and consulting on theory, policy, and strategic planning. An interdisciplinary thinker, his publications cover a range of fields including psychology, ethics, science, management, organizational learning, entrepreneurship, policy, and program evaluation with dozens of publications, hundreds of citations, and a growing list of international co-authors. In addition, he supports doctoral candidates at Capella University in the Harold Abel School of Psychology. Following a career in corrosion control engineering, he earned his PhD at Fielding Graduate University and took early retirement to pursue his passion – leveraging innovative insights on the structure of knowledge to accelerate the advancement of the social/behavioral sciences for improved practices and the betterment of the world. His textbook, with Bernadette Wright, “Practical Mapping for Applied Research and Program Evaluation” (Sage Publications) provides unique and effective approaches for developing new knowledge in support of sustainable success for businesses, government, and non-profits programs working to improve measurable results, individual lives, and whole communities.

featured image: DOUG MILLS /NYT

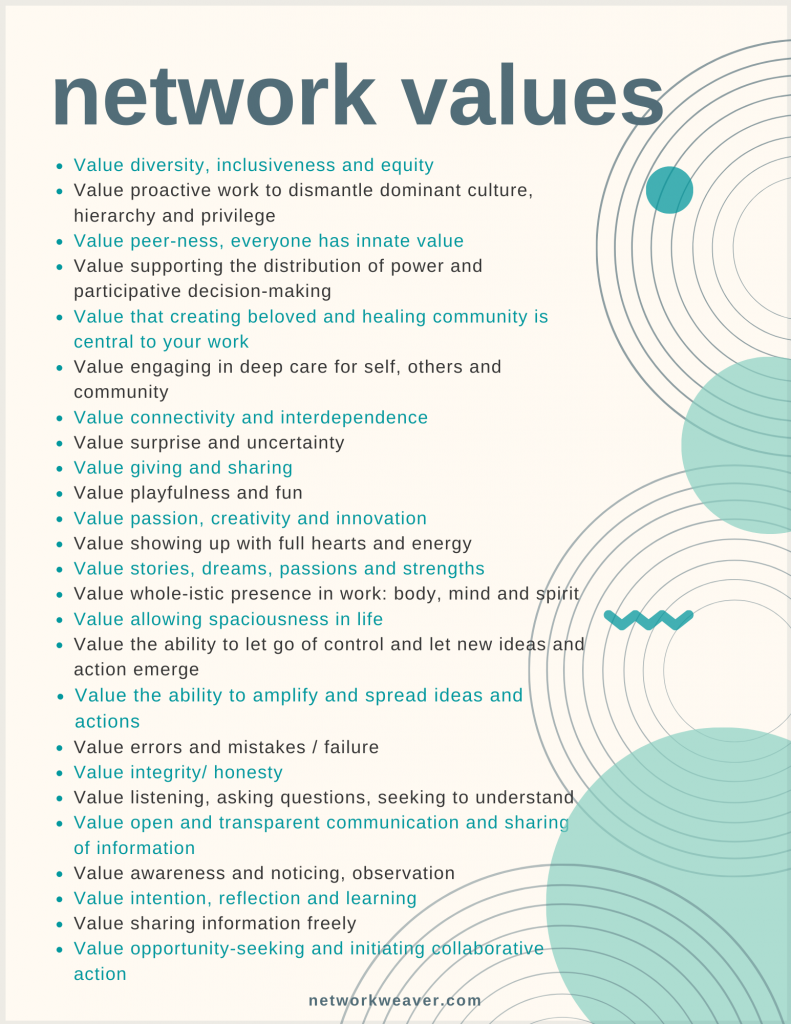

NETWORK VALUES

Having a group or network take a values survey raises awareness of the values and behaviors that enable networks to be system shifting or transformational.

Network Weaver has published a Network Values Module. Within this module are links to two web-based network values surveys, along with instructions. Also included are printable versions of the network values surveys and a printable flyer of a compiled list of Network Values.

Download the free module HERE

PURPOSE OF NETWORK VALUES SURVEYS

The purpose of having a group or network take a values survey is that it raises awareness of the values and behaviors that enable networks to be system shifting or transformational. It also gives clear information about the specific value areas where they need to work together to help each other shift to more network ways of being. People take the survey, immediately see the aggregated results, and work together to develop strategies for shifting challenge areas.

It’s extremely valuable for groups of networks to take the survey every six months (or even more often at first) so that they can see the progress they have made in shifting to network values and identify areas that still need attention.

There are two values surveys in this module.

- #1 Network Values Checklist

- #2 Network Values Dashboard (for individuals and organizations)

The first one is for individuals. It is used to help individuals identify the areas where they are already behaving from network values. You can have the group aggregate the results of everyone who took the survey so that they can see to what degree they as a group or network have shifted to network values and behaviors.

The second survey has two versions of each question. The first asks the individual about their values. The second asks the individual to rate how their organization ranks in reflecting this value or behavior. Usually the participants will score higher than their organizations. This survey helps people recognize that they cannot simply shift their own values, but need to work with their organizations to shift the entire organizational culture – if they want to be transformative in their impact.

Download the Networks Value Module HERE

DECENTRALIZED NETWORKS PART II: THE REVOLUTION WILL BE BUILT ON TRUST

Read PART I: Decentralized Networks And The Black Radical Tradition: From Collective Organizing to Building Black Futures. HERE

In this month’s feature, Kei Williams shares their “activating moment,” touches on movement building tools and shares their admiration for structural networks that are not only principles-based but continue to grow and meet the needs of the community. Material for this blog was compiled and transcribed by Sadia Hassan from the Decentralized Networks and the Black Radical Tradition community of practice gathering in March, 2020. You can find the video of this presentation HERE.

Kei is a queer transmasculine identified designer, writer and public speaker. A founding member of Black Lives Matter Global Network, Kie’s work is to transform global culture towards the systemic analysis of structural racism. As Movement Net Lab’s StrategicNetwork Mobilizer, Kei creates powerful conceptual and practical tools that factor in the growth and effort of the most dynamic and emerging social movements of our time. Kei is also the Lead organizer for Safety Beyond Policing, Swipe it Forward, and Trans Liberation Tuesday.

Kei aims to use their platform to center communities who identify as queer, trans, gender non-conforming, and those living with mental illness. Before the lockdown, Kei was active in engaging communities in the Black Gotham Experience, an immersive visual project exploring the impact of the African Diaspora on New York City.

ACTIVATING MOMENT: HOT SUMMER OF 2014

Every organizer has an activating moment, a political event that pulls them out of the mundane rituals of everyday life into a political awakening. For Kei, it was the Ferguson Rebellion. A rebellion which spanned months and sparked protests in other cities. The rebellion, which resulted from the state sanctioned murder of Michael Brown, was the first time Kei saw America attacking its citizens in a hyper-militant way in response to young folks rebelling against police shootings.

LANGUAGE MATTERS: REBELLION VS RIOT

Ferguson is often called an uprising or a riot, reducing the well-organized and strategic collective actions of protestors to the haphazard and agent-less language of “violent unrest.” For Kei, the word rebellion honors the risk of organizers who choose to build community under surveillance as they continue to fight in the street against the state. Historically, the state has considered the rebellions of enslaved BIPOC people as disconnected from the systemic violence they endure in their everyday lives. One reason the Black Gotham Experience has been so important to Kei is precisely because it connects the struggles of enslaved folks who rebelled in 1712 and 1741 against the institution of slavery and Wall Street to the current collective struggle for Black liberation, what Marc Lamont Hill calls “a principled, righteous rebellion.”

COLLECTIVE ORGANIZING IS A BLACK RADICAL TRADITION

Ferguson benefitted so much from organizing that was already being done by local Black Lives Matter chapters operating loosely in various cities in response to police shootings in 2012/2013 (Trayvon Martin, Rekia Boyd, Shereese Francis). What Kei saw in the three to four years of organizing with the Black Lives Matter Global Network was that movements have to be guided by principles, strive to create cultural change, and bear a rallying cry (Black Lives Matter, 99% vs 1%) that appeals to communities under attack. As a young organizer, Kei has appreciated stepping into the radical traditions that were developed by Black Lives Matter and the lessons learned from the Occupy Movement, chiefly that it’s important to foreground what is being fought for as much as what is being fought against.

Questions to ask as you lean into organizing:

- What exists beyond the moment?

- What does it mean to be in solidarity with each other?

- What are we fighting for/towards that’s gonna be a transformative system?

THE FUTURE OF THE DECENTRALIZED NETWORK

BLM NYC Chapter helped create a lot of the structural webbing for the Global Network. People like Allen Frimpong, Arielle Newton, Monica Dennis had been working with June and other decentralized Network Organizers to determine what the structure of the Global Network was going to look like and what was power going to look like in all of these different places. We have a history of hierarchical structures in organizations but it takes radical imagination to have a decentralized network that is uniform but can grow to scale.

Questions to ask when building decentralized networks:

- What does a decentralized structure look like?

- What needs to be done differently?

- How can we grow it to scale?

- How will we know when to keep it localized?

- What is power going to look like?

- Where am I? Where am I going?

- Where do I/my skillsets fit in?

ORGANIZING HAPPENS THROUGH RELATIONSHIPS

You have to have trust and good relationships for any organizing effort to work.

In 2014, organizers learned that detainees in the Federal detention center (MDC) didn’t have heat and were being kept in their freezing cells in the middle of a polar vortex. Two close friends called Kie and asked them to come down. Kei felt compelled to show up as a movement organizer and friend because of the relationships they had built. Over fifty people joined the action and occupied the parking lot, staying for 3 weeks. People slept in tents with propane heaters. Medics signed up to wake folks up every thirty minutes.

What came out of that small occupation was a sense of solidarity and a network build-out of medics, emergency responders, family and friends who continued to organize for detainees at MDC. People were brought in based on how they fit, what skills they offered, who they were connected to and could support.

Some principles of Decentralized Networks that create cultural shifts and community action:

- Relationship & Culture of Trust

- Looks like: building a culture around trust and communication

- Self-Organizing:

- Looks like: a culture of empowerment, self-determined and innovative work flows

- Structure and support:

- Looks like: twitter hashtags, cultivating alternate/virtual convening spaces (slack, mighty networks, etc), liberating structures, learning pods

NO NEW JAILS NYC CAMPAIGN:

BLM NYC and a lot of other collectives came together and created a de-centralized, multiracial, intergenerational network. First order of business was to create a network mapping to map the people who were in the room and what they wanted to see.

One of the accomplishments of No New Jails NYC is the conversation about abolishing jails and releasing incarcerated people that have become amplified during the pandemic. The demand came from decades of organizing as black and brown people and is abolitionist in principle. The current campaign that brings them all together is the Free Them All for Public Health campaign. Culturally, there was already a framework and a cultural language that influenced the Free Them All for Public Health campaign which began with #CLOSErikers in response to Khalief Browder’s death and now in response to Covid19.

Free Them All is going global, to focus on incarcerated people worldwide. The first thing it did when the pandemic began was lead a soap drive with jail and prison abolition networks. They understood how covid19 was going to face huge risks because the state of the jails are inhumane. Decentralized organizing means trying to look at things as a hub of demands and circles of support. It’s important to get plugged into mutual aid but as network and movement builders we have to lean in and build other movements. We have to find the scaffolding where movements overlap and maximize impact.

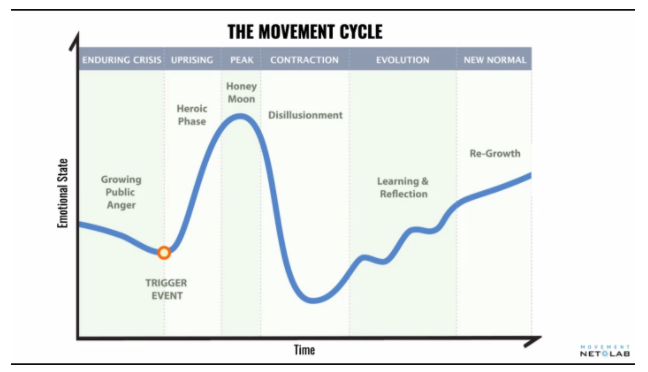

KNOW YOURSELF, KNOW THE CYCLE

As “networked social movements” continue to transform the political landscape, Kei emphasizes that Movement Net Lab has grounded their language, curriculum, design sense, and style in how they approach decentralization. Here is a map they’ve provided that illustrates the flow of a movement cycle so we can better map our interventions alongside it’s ebbs and flows.

It’s important to know the constant flow of a movement cycle.

1. Urgency overlaps with a sense of history → Trigger moment: Eric Garner → Heroic Phase: we’re gonna win → Honey Moon: action, in the streets/protesting, sweet moment where anything feels possible→ Disillusionment: didn’t get the demand → Reflection: what we learned, who we worked with, shouldn’t work with → Regrowth: what now?

2. Movement cycles allows us to map and build off of legacies that have existed for a long time

3. Knowing the movement cycle helps clarify where our skills best fit and where interventions can be most effective

If you have any questions, concerns or corrections, or to pitch a blog post please email us at networkweaverblog.com.

watch the video of the session by downloading the free resource HERE.

About the author:

Sadia Hassan is a facilitator and network weaver who has enjoyed helping organizations use a human-centered design approach to think through inclusive, equitable, and participatory processes for capacity building.

She is especially adept at facilitating conversations around race, power, and sexual violence using storytelling practice as a means of community engagement and strategy building.

She is an MFA candidate in Poetry at the University of Mississippi and has a Bachelor’s degree in African/African-American Studies from Dartmouth College.

BRAVE QUESTIONS: RECALCULATING PAY EQUITY

Asking Brave Questions

Perhaps it was a gutsy move. The four of us, a multi-racial team of independent consultants for social justice organizations, working with a local food justice nonprofit on values alignment, including pay equity. We sat in a circle in our client’s empty office to negotiate and decide how we wanted to distribute the contract.

A little more context might help you understand how we found ourselves at this conversation in the first place. Our team consists of Richael, Mala, Julia and Rebecca, the four of us are close friends who socialize with each other’s partners and families, we work together on other contracts and professional endeavors, and we support each other’s other vocational work and radical dreams from writing to workshops.

We, Richael and Mala, the authors of this blog, are queer people of color–Richael is a Black, trans-nonbinary folk healer, strategist, lawyer and former organizer who supports many parts of Black, Indigeous and People of Color (BIPOC) movement community; and Mala is South-Asian queer nonprofit strategist and human resources professional who has been thinking about, creating resources, and furthering racial justice lens, within organizational development work for decades.

Our other two friends and colleagues are white and (upper) middle-class folks (who have differences across religious backgrounds, parents immigration histories, regional identifications, and skill-sets) with backgrounds in prison abolition, Central American solidarity, food justice, resource redistribution, and who lead DC-area spaces for white folks to embody their own racial justice values. We each carry deep personal, political, and vocational commitments to racial justice, and we deeply respect one another’s experience and knowledge.

With our deep experience, comes an acute awareness that, especially with the world of organizational development and diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) consulting, how much of a gap can exist between what consultants tell organizations to do, but don’t practice themselves. Namely, as our team was supporting a white-led, multi-racial organization with long-time grievances about titles, advancement, and unequal pay among staff of color, we needed to do our own work to ensure that there was pay equity within our own consultant team. Simply put, we didn’t want to be the hypocrites that we critiqued. We were working with a local food justice org to address pay equity, but we were also facing critical choices about directing money that we were earning that would allow us to feel in integrity–or not.

On one hand, we could have used a couple of standard ways to price projects. Based on our proposal, which estimated $150/hour rate for convenience, we could have calculated our estimated hours per month, assigned the hourly rate, and let our consideration end there. Honestly, this is how a lot of consultant work goes, it’s fairly simple and efficient, and doesn’t require a lot of precious energy or critical thinking.

And, on the other hand, we suspected this standard did not allow us to live our walk. Using a standard hourly rate without examining how we got here or what work we each were holding would simply mirror biased norms. At that singular moment, the convergence of our work came toan opportunity to make a bold decision. We called it out: What are the values we want reflected in this distribution?

Our conversation started, informed by our lives, research, and professional work. We named the factors that represented the values important to us:

- “Historical discrimination1.”

- “Net worth – wealth, not income2.” We ended up taking both wealth and income into account because the data shows both matter when looking at disparities in economic opportunities between black and white households.3 .

- “The number of people you support through this income4.”

- “Emotional labor5.”

- “Monthly expenses6,7.”

- And finally, “distributed and anticipated inheritance8,9,10,11.”

At the end of the conversation we were led to a much more complex set of factors than standard hourly billing could account for, and we recognized, at this stage, we needed to generate a tool to help us identify our individual rates. Our goal was to create a distribution structure that actually felt fair for all of our systemic realities which most compensation systems don’t consider (perhaps intentionally). We came up with a collective ranking and applied that to the total compensation.

To do that, we customized a pay equity process and calculator, developed by our human resources expert, Mala, which reflected each factor that we called out, along with a list of other factors based on basic needs (e.g. minimum and maximum acceptable pay rate). We each had to go through the uncommon process of collecting accurate financial data from our households, businesses, partners, and parents. Once we collected these data, and plugged them into the calculator that Mala developed, we began to use it for billing our client, which we refined with feedback and revisions.

What did we discover?

We found that our white team members significantly underestimated their own net worth and their parents’ net worth by millions, while Richael under-estimated their parents’ liabilities, which had dramatically changed in the last few years. Ultimately, we learned that despite our middle class appearances and racial justice commitments, we were the wealth gap statistics.12

We also found that alongside the statistics were: raw emotional reactions, values, tensions based on our beliefs and systemic locations, and open questions about the echo of meanings within these revelations. And yet, in our team reflection, the Black team member said this was the first time they didn’t feel resentful about their compensation within a group. We were getting closer to equity.

This real-life experiment has shaped how we think about our racial equity organization work, too. When we offered our pay equity process and calculator as an example of what was possible to our client’s staff members, we experienced a range of responses, from flowing tears of a Black program staff member (being recognized for the historical and present-day discrimination and bias she faced and had to overcome to just get a seat at the table), to polite defensiveness of a white director.

We knew immediately that we were tapping a racial equity vein not only at this organization, but within the sector and beyond. What could the life blood within our workplaces and movements feel like if we shifted the payscale and internally strengthened protections? Could social justice organizations be the source of a private reparations movement to make workplaces fairer and more effectively make market corrections?

Many people are under the impression that making public our salaries, our wealth, our access to resources is illegal. Far from it—in fact, labor regulations prohibit retaliation against workers from sharing their salaries with one another, which essentially bars policies that prohibit workers from having salary conversations. Still, many businesses have created personnel policies that prevent salary sharing, even though it’s against the law, because our modern work culture standards are set by corporate America. Income secrecy is a divisive cultural tool that fits Friedman’s free market capitalist logic, because it benefits the 1% and other mega-beneficiaries of the corporatized economy. Simply put, we don’t have to abide.

What we need to do is acknowledge that there is shame and hurt in how much racist policies have privileged some and oppressed others. Let’s not blame ourselves in the 99%. We’ve been pitted against each other long enough. But once we know the impact of these policies–including decision-makers who can make different choices, and those for whom decisions have been made and who are able to advocate and organize toward equity–let’s act.

If you have benefited from these policies, voluntarily redistribute. Voluntarily, because we are all stronger for it. When 25%13,14 of us who have been privileged voluntarily redistribute because it’s the right thing to do, the scales of justice and social pressure will turn people to do the right thing (not because of the law). The last vestige of holdouts will be moved when the law no longer hides their privilege or when their children who inherit their wealth, whose values are more justice-centered, can redistribute for them.

1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2915460/

2 http://www.lchc.org/wp-content/uploads/02_LCHC_EconJustice.pdf

3 https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/2019-economic-commentaries/ec-201903-what-is-behind-the-persistence-of-the-racial-wealth-gap.aspx

4 https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/01/the-number-of-people-in-the-average-u-s-household-is-going-up-for-the-first-time-in-over-160-years/

5 https://hbr.org/2010/09/why-is-it-that-we.html

6 https://results.org/wp-content/uploads/2019-RESULTS-US-Poverty-Racial-Wealth-Inequality-Briefing-Packet-Section-1-Final-2.pdf

7 https://s3.amazonaws.com/oxfam-us/www/static/media/files/bp-reward-work-not-wealth-220118-en.pdf

8 https://academic.oup.com/sf/article/96/4/1411/4735110

9 https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/31206/1001166-wealth-and-economic-mobility.pdf

10 https://equitablegrowth.org/race-and-the-lack-of-intergenerational-economic-mobility-in-the-united-states/

11 https://www.wilsonquarterly.com/stories/why-rich-kids-become-rich-adults-and-poor-kids-become-poor-adults/

12 We see our experiment as a form of inter-personal reparations. Learn more beyond our example. https://wellexaminedlife.com/2016/04/20/the-case-for-inter-personal-reparations/

13 Centola, Damon, et al. Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention. Science. Jun 08, 2018.

14 Centola, Damon. The 25 Percent Tipping Point for Social Change. Psychology Today. May 28, 2019.

Mala Nagarajan (she/he) is an HR consultant that works with small-to-midsize nonprofits in practicing values-based, people-centered, and movement-oriented human resources management. Mala is a systems thinker and strategist; a racial and disabilities justice advocate; and she thrives on working at the edge of innovation, developing custom client-centered tools like the Pay Scale Equity Process and Calculator(TM). As a member of the RoadMap consulting network, she has coordinated their HR/RJ working group, supported their My Healthy Organization and Our Healthy Alliance online assessments tools, and works with multiracial teams to untangle thorny equity issues embedded in organizational culture, structures, and systems.

Richael Faithful (they/them) is a multidisciplinary folk healer, facilitator, strategist, creative and lawyer. Part of their work supports groups that are developing healing culture and practices with analyses of power and systems. Learn more about Richael at: www.richaelfaithful.com

featured image by Micheile Henderson

DECENTRALIZED NETWORKS AND THE BLACK RADICAL TRADITION – PART 1

FROM COLLECTIVE ORGANIZING TO BUILDING BLACK FUTURES

Every second Thursday of the month, Network Weavers Yasmin Yonis, Kiara Nagel and Marie DeMange host a Community of Practice conversation on Zoom. The skill-building space is available for network weavers who want to create connections and to explore questions central to their roles as facilitators, consultants and movement builders.

In March, the Community of Practice session was dedicated to unearthing what the Black Radical Tradition can teach us about how communities are self-organizing under crisis. Digital Strategist, social entrepreneur, and faith-based organizer Jayme Wooten and former organizer and founding member of Black Lives Matter Global Kei Williams, led the session through a riveting presentation that highlighted how network weaving in movement building creates strong, sustainable, and participatory avenues of community engagement.

In this first installation, I’ll be exploring some of the ideas that resonated with me from Jamye Wooten’s presentation. Join us next week for a second blog post on Kei William’s reflections on the difference between a riot and a rebellion, identifying key moments in a movement and power mapping.

What Moves You to Organize?

One of my key takeaways from the conversation was a question Jamye offered up to the group early on: “How do we move beyond react-ivism to a framework that is more wholesome and holistic?” When I think of activism, I think of forward movement, critical response to urgent community needs. What Jamey’s question opened up for me was an opportunity re-examine the impulse to act. Activism often comes out of a reaction to a perceived injustice. That reaction while visceral and binding, while it galvanizes communities towards action also depends on the viscerality of a trauma response for endurance.

Some good questions to ask in community:

Where in our organizing have we mistaken “react-ivism” for “activism”?

What can we offer as a community in its stead?

Is there room in our reaction to great harm for quietude and spaciousness so that we can recover and organize alongside our comrades?

What Kind of Network Makes a Movement?

A robust and inter-related one.

Another great offering from Jamye was an invitation to look closer at the parallels between movement building and Network Weaving. While people might remember Martin Luther King or Phillip Randolph as leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, what made the movement successful were core members like Ella Baker who helped local leaders in southern communities activate talented and capable young folks to self-organize. [1]

At the core of every network is a relationship, Jamye offers, and crucial to that relationship is trust. We often overlook the importance of relationship and trust building in the health and longevity of networks in an effort to make sure more work gets done, and yet, a sustained, years-long trust-building effort is the only way Baker’s could have galvanized as large and loose a coalition throughout the South as she did.

To that end, it’s important to know what each network needs to be able to organize resources to ensure its success. For example, an Action Network is just a collection or clustering of people who are interested in executing similar tasks: fundraising for an event or creating a mutual aid pod. What an Action Network needs to thrive might be different from a Support Network which is likely the comms and evaluations core of any successful self-organizing pod. That being said, a good Action Network is nothing without a robust Support Network, a collection of folks willing to build out systems and stay on top of resources. And a robust Support Network relies on the trust building, collaboration and thoughtful strategies that come out of relationships in intentional networks. Networks are not so much separate pods with a shared core as they are a spider

Are you using a Centralized vs. Decentralized Models?

According to Jamye’s research, successful Networks are not so much spidery pods with a powerful core as they are a starfish with deeply interconnected and communicative limbs. Thinking of the limbs of the Starfish as replicable and healthy parts of a network allow us to see the importance of each part: Circles, The Catalyst, Ideology, Pre-existing Network, The Champion. A healthy network needs all of these parts to be aligned in vision, communication, interlocking values and principles so that they can adequately organize for power.

A great example of such a model in practice are the hashtag based campaigns such as #BMoreUnited in response to the spotlight on Baltimore in the aftermath of Freddie Grey’s shooting at the hands of Baltimore Police. What emerged was a coalition of citizens who operated as a network without any real leadership structure to demand justice and accountability for police shootings in their community. They were able to do so by prioritizing participatory democracy and building out a skills bank to utilize the human and financial resources that came pouring in after the media spotlight.

From Collective Organizing to Building Black Futures

The last and arguably coolest lessons from the session is that it’s possible to use digital spaces to ethically organize on behalf of communities in ways that are participatory and rigorously innovative. Take CLLCTIVLY “a place-based social change ecosystem using an asset-based framework to focus on racial equity, narrative change, and social connectedness.” The most remarkable aspects of CLLCTIVLY: its asset map/directory which aims to amplify and connect community members with multimedia projects, a strategic partnership/marketplace, a social impact institute, and a rotating Black Futures Micro-Grant . Using the seven principles of Kwanza, CLLCTIVELY aims to put old money in service of new values. COLLECTIVELY- create ecosystem to foster collaboration.

Resources:

- Old Money, New Money 2019: A Community of Practice in Three Parts

- Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision by Barbara Ransby

[1]https://time.com/4633460/mlk-day-ella-baker/

Watch the video of the session by downloading the free resource HERE.

About the author:

Sadia Hassan is a facilitator and network weaver who has enjoyed helping organizations use a human-centered design approach to think through inclusive, equitable, and participatory processes for capacity building.

She is especially adept at facilitating conversations around race, power, and sexual violence using storytelling practice as a means of community engagement and strategy building.

She is an MFA candidate in Poetry at the University of Mississippi and has a Bachelor’s degree in African/African-American Studies from Dartmouth College.

WHO AM I

Adhel Arop is a two time award winning filmmaker from Vancouver, Canada. She has been a poet since the age of eight, writing poems for conferences and school assemblies. She has always gravitated to poetry as a way to express and explore emotions.

Adhel’s documentary “Who am I?” weaves together her experience settling into Canada as a refugee with her family and her mother’s experience as a child soldier in South Sudan. We are excited to share two of Adhel’s poems, Sudan’s Echo and SPLA Song and a short interview with the artist about her influences and hope for her work.

PART I.

(This is the translated song that my mother and I sing at the end of the documentary.)

Sudan’s Echo

By: Adhel Arop

The sky weeps

my country screams

I watch in agony

the eyes of the people I love dearly tell stories of sadness

they are children

who have become broken adults

Now their children inherit that hurt

trauma becomes Sudan’s

greatest

Legacy

I remember the music that played in the background of my childhood

my mother seeking solace in the things that destroyed her

I would look into her eyes

Seeing the reflection of the skies

she once looks up to

her face

crying out as muffled voices screeches from the radio

eyes fading into an expression I could not understand.

We were strangers

she was strength

yet in her power I saw weakness

every day

I heard these muffled voices

Hopeful screams

they were my mother’s sense of home

she gave up her childhood for her country

within that exchange

her eyes stopped forming tears

while her soul drowned in agony

What has become of the person she wished to be?

I remember hearing the muffled voice of men

seeping out of the radio

the sounds lingered in the air

longer then the silent stares we exchange

I would whisper

“are you ok?”

She looked at me

our hearts exchanged words our mouths could not

never understood why these cassettes meant so much to her

How was I to know she had been a child soldier

These muffled voices of men screaming

were the songs that once kept her alive

at a time she wasn’t sure if she wanted live

I weep for her

because I know

she has lost her ability to shed tears for

herself….

SPLA War Song

South Sudan wo yay

SPLA wo yay

Karyom wo yay

Madeer dan wa

Leaders of Wau

Madeer Wau (region in Sudan)

Leaders of Wau

Meedeer dan Wau

Leaders of Wau

Ran Wau

People of Wau

Madder dan Malakal wandeed ku juba

Leaders of Malakal l And Juba

Loy by ka de ken pel a by

What are we doing to our country

bogou thiem chin te de e ya chol

You’ve left our country in shambles and have nowhere to call home

Maye maye maye

My god, My god

Maye maye maye

My god, My god

Meerder yat kwon acha keg pwol

You’ve homes, your province

Ke dom ke lwoy che by la tweng

and taken on jobs that wont help the country develop

E ke reg a de

What a terrible thing

Wed kwan Sudan

Children of Sudan

Howne a thiow thar a che la mang

That sounds of gunfire is going

Keg jej a Nemir

off as the soldier fight against us

Sonke sonke A mane a Nemir jol ke moge a choge

Nemir will hate it but we will take our country back

Bunge Kwan yin kej waii kuwa teng

Governor Haven’t you seen us we are dying

pinge by Sudan a riag bange da

Our Country is in shambles

pinge bwog liew

We can’t move forward

kowo che jur Maraleen Jok Kwa nhin win a Bol

we can’t take back our country when most of us have died

The arabs have chased us out

Kwa Nhin son of Bol

Name of Leader

Maye maye

my God, My Gd

Leke John Karang Leke John Karang bwog loy ke de Na ye piang da

Tell John Karang how will we take back our land,

Bunge Kwa nin kej wei kwa teng binge by Sudan a riag bange da

Governor Kwanin haven’t you seen us, haven’t you seen our country we are dying

pinge bwog liew kowo che jur

How will we take back our country when many of us have been killed by soldiers

Maraleen Jok Kwa nhin win a Bol

Tell us

Maya maya maye

My God, My god

Leke John Karang bwog loy ke de Na ye piang da

Tell John Garang what will we do to get back our land?

Nhwen a thow bwog rod nyia wei

When it comes our land We will die for it

Ghwen a thow wed kwan e two

You will only take our country over our dead bodies

Gwen a thow wed kwan Janub

We choose death, our life is our country

Biange john garang ina choge mouthe mathu biange da

John Ganag we salute you,

Ka pae ka dianhg owa nug neen jwij

its been 3 month we’ve been walk and we are tired

PART II.

Interview

Sadia Hassan: Adhel, I just watched your moving documentary. It is so full of love for your mother and you all’s shared language and common history. I grew up in Clarkston, GA where my family and I were resettled as refugees in the mid 90’s. I had lots of friends from Sudan and Gambia. Your documentary reminded me so much of what it was like (and honestly, still like) to grow in that middling place of multiple identities.

What of your work in the world inspired these poems?

Adhel Arop: My documentary “Who Am I” is the film to my poetry, I wrote these poems while creating my first film, I used them to hire collaborators, the set the tone for all my present work, I learned to translate Dinka (my native tongue) I got a deeper for my language, opening me up to a whole new world of stories, the history of my country South Sudan and my mother and aunts apart of the liberation movement, this feminine power in the face of war gave me courage to explore my mothers trauma.

SH: What do you hope readers will walk away with?

AA: I hope they hear the hope that echoes through time, the songs that my mother sang as a child soldier are now interweaved into my artistic platform raising my success as a filmmaker while honouring my roots. These types of stories are not unique. War and displacement have affected many countries and their development is intergenerational trauma something we all can connect to one way or another.

SH: In the age of climate change, what do you feel the world owes Sudan?

AA: I wont say the world owes Sudan anything, war owes Sudan peace. Centuries of fighting with the division between the majority Islamic North and a Christian South, one that led to two civil wars, leading to a referendum in 2009; these issues birthed a new nation called South Sudan, the newest country to join the UN, A country that has been plagued by civil war and continues the unrest after the referendum. These two nations, Sudan and South Sudan, are going to be heavily affected by the climate change.

The South is still on a first wave of industrial revolutions. I hope the world will aid Sudan and South Sudan in exploring solar energy for infrastructure building. As a human rights activist, I believe that at-risk countries need our support. They are behind on technology because of on-going war and with climate change and their effects will take have some concerning repercussions for at risk countries and Sub-Saharan Africa, the world should aid Sudan & South Sudan on their Sustainable Development Goals and infrastructure building through the use sustainable options such as Solar Energy, I hope the countries will be offered a voice and connected in the fight for Climate change as leaders.

SH: Can you tell us a little about a community practice you have that has inspired your art-making?

AA: I have been a volunteer mediation instructor on the downtown eastside, Karma teachers is a non-profit studio and teacher training school. Volunteering for the past eight months has provided an inside look at what goes into running a yoga studio the community that gathers. We all volunteer our time and help one another, It’s inspired my art to be involved in a community, my art has grown significantly through the developing love of all the communities I’ve been a part of. My art is to raise people’s voices that were once silenced through multiple digital mediums.

SH: What was your experience translating Dinka with your mom and what do you think the world of translation can do for us in terms of empathy and connecting with each other?

AA: Translating was definitely difficult when I originally took on the task, I translated over 40,000 words from Dinka to English. I would call my mom and ask her to re-pronounce certain words or songs. Dinka has several accents and I spoke/understood one certain accent, but after hours and hours of listening to different people speaking the language, I managed to have an easier time. I think that understanding breeds empathy and connection because it allows us the ability to understand each other. Learning Dinka more intensely has made me feel more connected to my mother. It gave us something to do together. People from my community have really been happy with my interest in exploring the culture and language, providing me with opportunities within the community to learn to speak and translate the language.

SH: Sudan’s Echo is entirely in English while SPLA Song almost feels like a call and response between English and Dinka. What feelings were you trying to evoke with each poem? Are they in conversation with each other?