Building Trust Through Grantee Feedback

A Conversation with Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies

In CEP’s recent publication, New Attitudes, Old Practices: The Provision of Multiyear General Operating Support, nearly all interviewed foundation leaders emphasized the importance of trust between funders and grantees. Moreover, CEP found that foundation leaders who provide more multiyear general operating support made an intentional choice to do so based on their belief that it will build trust, strengthen relationships, and increase impact.

When Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies (RNP), a foundation located in Bangalore, India, gathered feedback from its grantees through the Grantee Perception Report (GPR) in 2020, RNP was rated in the top 1 percent of CEP’s overall comparative dataset for perceptions of trust. Simultaneously, RNP grantees rated in the bottom 1 percent of the dataset for the amount of pressure they felt to modify their organization’s priorities in order to receive funding from the foundation.

How did RNP achieve this? To what practices does the foundation’s team adhere to build trust with grantees in their interactions? How do they think about trust-based philanthropy?

For answers to these questions, we recently talked to members of RNP’s leadership team: Founder-Chairperson Rohini Nilekani (who, with her husband Nandan Nilekani, has signed the Giving Pledge), Director of Strategy Gautam John, and Associate Director Natasha Joshi.

The team explains their approach in this new video:

Here are some more thoughts from Nilekani, John, and Joshi on several key elements of centering trust in their approach:

Starting with Trust is Important

Rohini Nilekani (RN): We’ve all been on the other side (of the funding table) and know how hard it is. Things change so quickly on the ground. We need to be agile and can’t be stuck with budget lines or line items that we have to stick to. Of course, you have to do due diligence, but if you don’t start off assuming the right intent and methodology on the other side, then what are you going to do? Then you must take over and do it yourself. When you’ve found the right leaders and institutions, you have to let them do what they believe in. Because passion and commitment are what drive this sector.

Just like you can’t tell Picasso to use a little less red or blue when you commission a painting from him, you can’t tell civil society organizations, “Okay fine, but just do it my way a little more.” It won’t work! Starting with trust, after basic due diligence, seems to me not just a moral but also a strategic imperative. We have to first try trust — always.

Gautam John (GJ): I’ve spent 10 years working as a grantee trying to raise money from foundations. And in my experience, you can’t co-create by saying, “Do it my way.” That’s not co-creation, that’s called convincing. Our goal is to create something together. Co-creation is difficult because it means letting go of some degree of control — and that’s hard to do.

The Need for Humility

RN: If you keep chasing attribution, you become your own chokepoint. In philanthropy, it’s more important to recognize contribution, rather than seeking attribution. I can’t see how you can achieve the philanthropic goal behind what you want to achieve by chasing attribution. You have to hold your goal close to heart and be willing to trust others. Nobody can go at it alone.

Honestly, none of us know how change really happens. We only have some theories about it. I try to walk back from too much certainty; to occupy the grey and occupy doubt; to think, “My ideas may not be right”; to not allow myself to say, “I am right”; to keep a mirror in front of myself. Yes, there may be occasions where your perspectives may be understood and absorbed. But if you insist on doing things your way, you’ll only get a service provider, not a partner. You’ll end up with a contractor or vendor relationship, rather than with a partner who you can walk with.

GJ: Philanthropists usually wake up in the morning saying, “We know all the answers,” when really, we should be waking up with questions. Because the idea of co-creation comes from being willing to let go of some amount of control and to act from a place of humility and curiosity. Humility is rare in the philanthropic sector. “We don’t always know — you do, and we might be able to learn something from you” is what we need more of.

More Long-term, Flexible, Unrestricted Funding

Natasha Joshi (NJ): Rohini Nilekani deliberately chose not to set up a registered foundation. We were afraid of creating too much bureaucracy because sometimes, too much bureaucracy can make it hard to be flexible and responsive in your giving.

GJ: High-quality civil society organizations deliver high-quality outcomes. You can’t have one without the other, so one needs to be willing to invest in their organizations, their people, and attract talent.

Strangely, many philanthropists don’t behave with their nonprofit partners the way they do in their businesses. How people see for-profit companies versus nonprofits can be very different; the very same person can have completely different views on how capital should be used. I legitimately struggle with this and I don’t know where it comes from. In India, perhaps, it’s because the idea of ‘service’ has a long and deep history. On the other hand, I hear philanthropists bemoaning the lack of talent in the civil society sector. But you can’t have it all without being willing to invest in organization building by committing to long-term, unrestricted funding.

RN: Some philanthropists are nervous about trusting civil society organizations. In India, at the onset of Independence, and 60 years later still, many civil society organizations were Marxist and left leaning. Businessmen, who are usually philanthropists because they are the ones with access to capital, are usually more market leaning. This creates a political ideology divide. As a result, philanthropists in India don’t even get into trust modus. Rather, they create their own independent implementation arms. This means that you don’t have to trust anybody. The question of trust can be bypassed because you can do it all by yourself.

Of course, when trust is broken, you can pull back and create more rules. There are things that we can do. But when you have a car accident, it also doesn’t mean you never get in the car again.

But like I said, in order for real social change to happen, nobody can go at it alone. One has to always try trust first.

About the author:

Charlotte Brugman is manager, assessment and advisory services, at CEP. If you’d like to learn more about understanding and improving your relationships with grantees, including through collecting grantee feedback via the Grantee Perception Report (GPR), contact Charlotte, who is based in Amsterdam and leads CEP’s work with global funders, at charlotteb[at]cep.org.

originally published at CEP.org

featured image found HERE

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

Reclaiming Choice and Agency in a Networked World

Welcome! We are happy you chose to open this blog post! In this article we will explore:

- The difference between choice and decision; and why awareness of choice matters - as a (fundamental) way to engage with life.

- Different levels of networks & systems and how to navigate the levels with agency.

- How to choose with your whole being - as a means to align your deeper values and actions.

- Exercises and prompts to practice choice as a capacity.

We believe that it can be of use to change agents, social innovators, system entrepreneurs, and curious minds. Most importantly: We invite you to choose to fully engage with the article and share your reflections with us. We have laid out some opportunities to do so on the way :)

So let’s dive right in!

Choosing to Decide

Each day we make numerous decisions, from what we consume, such as food and media, to how we respond to others and to our environments, and beneath all of these decisions are choices. Yet, what is the difference between a choice and a decision? A decision often implies reaching a conclusion you can act upon, in this process something is determined. While a choice implies an act of choosing between two or more possibilities. In this way, ‘choosing’ is a practice of continually aligning toward various decisions. If we zoom out we may see that choices are how we navigate through life and how we arrive at decisions. Let’s take a moment to ponder this.

What was the most important decision you made today?

And what was the underlying choice you made that led you to that decision?

Choosing and deciding are related processes, yes, but they are fundamentally different in their nature. Choosing is relational, it is a process of orienting ourselves towards something of importance, such as our personal values, and what we hold dear. Choices lay out possible paths and open up fields of opportunities. While, deciding is directional; decisions are the concrete steps we take on that path.

If we shift from considering the individual level of choice to the collective level, we can see that human actions are a dominant driving force for what’s happening, and going to happen, on this planet. From this perspective our actions may look insignificant at a larger scale.

But an easily overlooked perspective is that we are not passive consumers or bystanders in the course of history. There is choice and agency everywhere, in the seemingly small moments of our daily lives, in the conversations we have with loved ones, or in choosing, or changing, our careers. Each moment holds an underlying choice we can engage if we choose to.

Now, a common argument is that the challenges we are facing are so grand and complex - that it doesn’t really matter what I intend, do or think.

In this article we will flip this argument around: In a networked world, there is nothing that matters more than what you do. Not only for you and your immediate environment, but also for the world at large. What you do, in turn, is deeply embedded in the choices you make, as your choices shape your orientation toward life.

Engaging with choice can also foster your sense of agency. Agency refers to the ability to direct your own actions in a meaningful way. In the field of systems impact, agency is often the precursor to creating change within our immediate environment or the larger social context we exist within and care about. As we reclaim our sense of choice, we inhabit more of our agency, which in turn enables us to have a greater impact.

Before we unpack this more and dive deeper into the exploration on how to reclaim choice and agency, we invite you to do a little exercise with us, to connect with what supports your sense of choice and agency.

You can follow the steps below or use this mentimeter survey for guidance: https://www.menti.com/txm61jx7f7

(if you use the survey, we will anonymously keep track of the responses - and you can also read through the results of others for inspiration)

- Think of a current situation that frustrates you - where you feel you don’t have choice or agency. This can be something in your immediate environment - or a larger social issue. How would you describe that situation? What emotions are present for you? What is the root cause of your frustration?

- Now, think of a moment in the past where you felt similar, but then experienced some sort of breakthrough - a moment where new opportunities emerged. Enter that moment now. Take a few deep breaths and observe what shows up for you - in terms of images, emotions or intuitions.

- Now consider, what made that breakthrough, that shift, possible? Note down a few words, lines or images.

We will return to this exercise at a later stage in this article.

Agency in a Networked World

We all exist in webs of relationships, which are the most basic form of networks. Networks exist within and around us. In nature we see networks of mycelium, mushrooms and fungi; the internet is a network of networks consisting of computers, routers and webpages. If we consider our bodies we can see that even our brain is made up of neural networks and synapses. Networks show us that it is important to focus on the individual elements as well as the relationships between them.

In essence, referring to our world as “networked” mainly means four things:

(1) We are part of more networks than ever before. Just count the number of initiatives, groups and organisations you are connected to - and compare it to the generation before you.

(2) the networks we are part of are larger in scope than they have ever been. Technology, mainly the internet, has made it possible to decouple social connections from physical proximity, at least to a certain degree.

(3) The networks themselves are connected. what happens within one network impacts others, for example a traffic jam or delayed trains in a transport system can lead to people being late to work.

(4) The networks we are part of, or deliberately not part of, shape our identity and actions. In turn, we also shape the identity and possible actions of these networks, yet usually to a lesser degree.

Let’s explore one aspect further: having agency within a networked world. To distill things a bit, we can say that there are three major levels of networks. For simplicity's sake, moving forward, we will use the terms “network” and “system” interchangeably.

- Individuals: Human beings in their full complexity and wholeness

- Intermediary institutions: Systems we can belong to and that we can shape, e.g. a family, sports club, impact network, or organisation.

- Societal systems / institutions: governments, the financial sector, etc.

Now, there are connections within each system, e.g. between coworkers of an organisation; between systems of the same level, e.g. organisations within an alliance; and between systems of different levels, e.g. an activist group trying to influence a policy.

We each will have varying degrees of agency in relation to the three levels of networks mentioned above. For example, personally fighting financial injustice, individual level, by ignoring letters from the financial department, societal level, is not the most promising strategy. As individuals, we usually have very little leverage over societal institutions and matters. However, joining an organisation, an intermediary institution, that creates financial literacy among disadvantaged groups and lobbies for policy changes, might actually work.

With an awareness of each level it becomes easier to choose which level and interaction you say yes to and no to. Choices are an opportunity to lean in and engage with the networks within and around us. Yet we may often jump to decisions without being aware of the choices that are available to us. This awareness, from our perspective, is the first step towards reclaiming choice and agency.

Choice for Impact

In engaging choice for creating systemic impact, a key question is: What’s the issue or vision I want to contribute to? To achieve that, what is the relevant system that I want to change, and in which direction do I want to change it? Let’s apply what we’ve learned so far, by drawing on the concepts of choice and agency as well as the three levels of systems. To make this more tanglible, you can bring to mind the situation that frustrates you from the initial exercise, and take a moment to think about the societal issues that underlies it.

To move from inertia to agency, we see four levels of choice.

The first choice is about living into your values and allowing yourself to take your inner compass and drive for social change seriously. This can be in relation to a social issue or external “trigger”, such as observing environmental destruction or diversity loss in your area.

The second choice is to think systemically and be strategic, asking the question: what is the relevant societal system I can engage with in relation to this topic? This choice is context dependent and will vary depending on where you live, the resources you have access to, and which systems may be standing in the way of it becoming a reality. For example, there may be a larger societal system that needs to be shifted, such as the energy supply system with its given sources of energy and the extraction of these resources.

The third choice is to engage my agency and seek intermediary institutions to engage in. It’s a choice to be proactive about changing the status quo with an attitude of both realism, “we should do something or else..”, and optimism, “there is something I / we can do”. Taking the example of climate justice, this might result in joining an energy coop or an activist group to influence politics.

Lastly, the fourth choice is to remember the choices above and embody them with joy and a sense of optimism. We can only be effective change agents if, to paraphrase Gandhi, “our lives are our message”.

Our modern day and age provide us with the unique opportunity to use network effects on a global level to contribute to causes we care about. The Four Levels of Choice can serve as a general orientation, acknowledging that it’s rather circular and interdependent than linear in its application.

Another way we can understand the levels of choice is through imagining an iceberg. Part of the iceberg is above water yet the majority of the iceberg exists beneath the water's surface. The part below the surface represents our values, beliefs and mental models, while the part above the surface represents our behavior and actions. Choice is how we align what is beneath the surface, with what is above the surface, therefore aligning our values with our behavior and actions.

We invite you to go back to your personal situation and example, either for yourself or in the mentimeter survey: How can you relate differently to move from frustration to agency? What are the underlying choices you have?

To give the topic more depth, there are two additional perspectives we’d like to explore, starting with ourselves and the choices we have within.

Choices within

Choice is in essence a process of alignment. At the deepest level choice can be seen as aligning with life, both in a general sense and in the present moment. Through choice we can also engage the intelligence of our body, our senses, organs and our imagination, in noticing what arises in response to a particular direction. Upon waking up in the morning, you can ask yourself ‘what am I choosing today?’ and then notice what arises, not only in the realm of thought, but also through sensations, images, textures, sounds and other experiences. Over time, by cultivating an awareness of how we respond to a given direction, we become able to choose more fully from our whole being and find greater alignment in our subsequent decisions.

At one level these choices within are momentary. They can arise through what we give our attention to, how much we open ourselves to experience something, and how much context to bring in and share with another. Choices can also span time and serve as a north star. For example, choice can manifest through a sense of calling, something we choose again and again that moves us closer to a dream we have for the world. As such, choice becomes the fuel for moving forward. Choice in that sense is an ongoing journey. As we pursue our calling we can reflect on the values we are choosing to enact and the principles we are choosing to embody in service of those values.

Here are some guiding questions to work with choice as an ongoing journey and a calling:

- What is so dear to you that you are willing to choose it over and over again?

- What is choosing you? What are themes you repeatedly run into?

As stated earlier on, our choices reveal our basic attitudes, beliefs and feelings toward life.

Choices underlie our decisions; they move us from thought into action.

Choices in Impact Networks

Yet there is still another dimension of choice, namely within networks or intermediary institutions. We can see these choices through the levels we outlined above as well as in any context where we exist in relation to other beings. An example of this kind of intermediary institution is an impact network, a network that is intentionally created...

Here we can see that there are two fundamental dynamics at play.

In the first dimension such a network coordinates and synergizes individual actions around shared principles and a collective purpose that individuals have chosen to participate in. The purpose of the network may not mirror the individuals’ purpose, however there is usually a synergy between the individuals’ purpose and the purpose of the network.

In the second dimension, impact networks support and carry out collaborative action and learning for deliberative change on social and environmental issues.

Choice shows up in each of the two dimensions within an impact network:

Dimension 1 is about choosing how to create the best possible conditions to engage network members. This requires the network to provide incentives to individuals to actively engage, and at the same time recognise the overall purpose and strategy of the network. For example, establishing rules around membership and criteria for internal decision making.

Dimension 2 is about choosing how to relate proactively to the societal issue and its related system(s). Impact networks, therefore, are an ideal testing ground to practise agency and choice in an intentional way.

Practicing Choice

We’ve seen that the decisions we make are often preceded by an underlying choice we’ve made at a conscious or subconscious level. When we connect with the dimensions of choice we can connect with a greater sense of agency in our immediate context and within the larger systems we are a part of. This awareness, in turn, supports us to become more intentional and impactful in the decisions we make and actions we take.

Choosing is also a capacity that we can cultivate through practice. Throughout each day we can notice the choices available to us and choose to engage our choices consciously. Awareness is the first step. We can practice recognizing the choices we have in the moment as well as the different dimensions that we can engage our choice in. Choosing deliberately increases our agency - the ability to direct our own actions in a meaningful way.

Choices help us to orient ourselves towards the world we wish to create- with all its complex challenges.

It’s a practice, like building a muscle or learning a new skill.

With this article we hope to provide an accessible framework to rethink and reclaim choice & agency, to invite each of us to begin to practice engaging the choices we have, from the large, to the seemingly mundane or small.

The following worksheets are designed to support you in that practice:

- Choosing for impact (4 steps)

- Choosing with my whole being

- Choosing and being chosen: exploring our north star

Download all 3 worksheets in one package HERE

Happy choosing! All worksheets are under a creative commons license, so feel encouraged to invite friends, colleagues and whoever comes to mind into the practice.

About Elsa & Jannik - the authors

This article is a co-creation in the truest sense. We noticed early on in our explorative conversations that we share interests and perspectives on many topics, such as impact networks, creating and evaluating systemic change, and capacity development. We also recognised our complementary backgrounds.

Elsa Henderson is a practitioner at the Converge Network and faculty at the Metavision Institute. She moves between the roles of network consultant, facilitator and educator supporting individuals and groups to deepen their capacity to collaborate for systems impact and find meaning even in the midst of uncertainty. Her background is in process-oriented psychology and anthropology, with an interest in phenomenology, systems thinking and consciousness studies.

Jannik Kaiser is co-founder of Unity Effect, where he leads the area of Systemic Impact Evaluation, grounded in the knowledge that evaluation can be participatory, meaningful and energising. His background is in sociology, with a continuous passion for complexity science, phenomenology and asking fundamental big questions about life.

In our conversations, we also allowed our minds to wander and our intuition to speak. In the end, it felt more like the topic of choice ‘chose’ us. And we could feel the depth and richness in it that is calling for further explorations.

To give one example: The image of the iceberg and choice as a process to align our values and principles and translate them into action. This aligns with the three levels of reality process-oriented psychology, namely (1) consensus reality, (2) Dreamland (inner worlds & imaginations) and the (3) Essence level (the non-dual pre-manifest field of ‘implicate order' as coined by Bohm. It also fits with Ken Wilber’s AQAL model, according to which each system has an interior (invisible) and exterior (visible) dimension.

An interesting exploration could be how individual and collective choices are connected. The iceberg is swimming in a vast ocean of water. Similarly, our individual choices are embedded in what we could call consensus reality or culture. Yet this consensus reality is currently being questioned, and the topic of choice could inform how we transition between such collective realities.

So stay tuned, there might be more coming up.

originally published at Unity Effect

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

Return on Relationships: Four Ingredients of Trust

Trust has become something of a buzzword. Most people will acknowledge that it’s important, yet many see it as a byproduct of other activities, rather than something that should be cultivated deliberately.

On the contrary, the web of connections that develops between participants is the invisible structure that holds all types of collaborative communities together, including working groups, networks, and DAOs. A failure to cultivate trusting relationships is where many communities fall short.

Trust is the element that makes possible all of a community’s other virtues and accomplishments. Specifically:

Trust creates cohesion while a community’s more formal structures and processes are being formed. Nascent communities are unlikely to have many formal agreements in the early stages of their evolution. During this time, it may be difficult for some participants to sit with the ambiguity. Trusting in each other and in the group helps people to be more comfortable with emergence—to explore, experiment, reflect, and self-correct in real time. People also become more willing to share information and take risks. Trust is the glue that keeps a group together as participants develop additional structures for organizing themselves.

Trust increases the group’s collective intelligence and avoids the pitfalls of conformism and groupthink. Under the right conditions, groups are capable of thoughtful discernment and collective intelligence greater than that of any single individual. Lack of openness to others’ perspectives is arguably the greatest obstacle to a group's ability to think and act intelligently. Our tendency, in the absence of trust, is to believe that our assumptions and projections are valid, that we know what others are thinking and feeling without asking them, and that maybe we are the only sane person in the room. Trust increases the likelihood that participants will listen with care, try on new perspectives, and engage with people they might consider to be very different from themselves.

Trust expands the range of possible conversations. People who trust each other are more forthright, more likely to share information, and more likely to show creativity in how they collaborate. With sufficient trust, people are better able to navigate through uncomfortable conversations and test each other’s assumptions without fear of harm. As a result, new perspectives are considered, and conflict becomes generative rather than destructive. The group’s ability to engage in constructive dialogue and make informed decisions grows as people feel free to speak their mind and acknowledge difficult realities or controversial points of view.

This shift has been critical to the success of the Clean Electronics Production Network (CEPN), a program of Green America’s Center for Sustainability Solutions, which has been supported by both Converge and the CoCreative consulting group. Participants of the CEPN include many major technology brands and environmental NGOs that are working together to address an issue that no single organization can solve on its own: moving toward zero exposure of workers to toxic chemicals in the electronics manufacturing process. Relationships between the electronics brands and NGOs were initially tense when the network launched in 2016. But over the past few years, “members have gotten to a point where they have enough trust to where they’re willing to share what’s working, what’s not working, and where they need help,” shares Pamela Brody-Heine, director of the CEPN. “Relationships have been transformed, and the communication between them is much more productive.”

Although it is widely accepted that trusting relationships are beneficial when it comes to collaboration, the common assumption is that trust is a byproduct of other activities and that it takes a long time to develop. Rather than deliberately building trust, the norm is to focus on getting to action and letting relationships develop naturally over time.

However, we have consistently found that trust is the single most important factor behind successful collaboration; communities move at the speed of trust. Therefore, trust should be deliberately nurtured from the outset of a community’s development. When working in collaboration with others, the time you spend cultivating relationships of trust is the greatest investment you can make—consider it a “return on relationships.”

Ingredients of Trust

Trust isn’t just a noun, it’s also a verb—it is something you do. It’s a choice people can make. We either choose to trust someone or choose not to trust them (or we can let our implicit biases make the choice for us). While trust takes time to deepen, we’ve found that it is possible to develop a foundational level of trust in a relatively short time.

Trusting another person requires an initial leap of faith, as it’s impossible to know exactly how things will turn out. The unfortunate reality is that by choosing to trust, you expose yourself to being burned. Nearly everyone has been betrayed at some point in their lives, and it can hurt, a lot. It hurts so badly that we might even put up a barrier between ourselves and others so it will never happen again. For some people who have been oppressed or experienced trauma, including intergenerational trauma, trust cannot be easily given—it has to be earned.

And yet, it’s hard to work with people you don’t trust. People collaborate based on relationships, not solely on ideas. Communities run on trust.

There are four primary ingredients that increase the likelihood that people will choose to trust one another, despite all the uncertainty that relationships bring:

- Reliability

- Openness

- Care

- Appreciation

Reliability

Choosing to trust people is, in part, a judgment that they will be true to their word and follow through on their commitments. Trust grows through action. When people help each other by offering support or contributing to a project, it builds a foundation of goodwill. And when people prove their reliability time and time again by continuing to show up, stick around, and follow through, trust grows to a level of resilience that can withstand significant disruption.

Reliability doesn’t mean that people always have to respond positively to a request for support. It’s important that people feel free to decline when they don’t have the ability or capacity to help. Without space for “no,” there is no weight behind “yes.” Being reliable just means that when you say “yes,” you will do your best to follow through and keep others informed if something goes wrong. On the flip side, reliability also means that when you decline, others will respect and hold you accountable to that “no” as well.

Openness

Inevitably, in any relationship, miscommunications and moments of tension will arise. People may strongly disagree with one another about what to do next. Without sufficient trust, these disruptions can derail the relationship and stall action. Overcoming these rocky periods requires openness—the willingness to be honest and share what’s on your mind, as well as the ability to listen deeply and consider new perspectives.

In the absence of openness, our true emotions and opinions are often guarded or hidden under a professional mask. We also remain closed to new information, stubbornly holding on to past beliefs and closing off new possibilities. To be open is to be willing to share honest thoughts and feelings, even if it’s uncomfortable. By being open, we acknowledge interdependence and invite reciprocity. It’s sometimes assumed that being open with one another comes later, after trust has been developed, but openness is also a great catalyst of trust.

At times, being open may simply be too risky. This is particularly true for those who have been oppressed or experienced significant trauma. They know firsthand that people can and do use their power to exploit others for personal gain rather than collective good. For this reason, make sure to allow people the space they need to engage or not, and to honor distance where appropriate. When openness is not yet possible, a mutual commitment to care may be a first step.

Care

For many, trust does not come easily, because past transgressions have revealed time and time again that people are not to be trusted. Often, the first step toward choosing trust comes when people recognize that others hold a mutual concern for something they care about. Even if it’s hard to trust another person directly, it might be easier to trust the love that someone has for their community or region, or for the network.

Critically, demonstrating care also involves acknowledging and then repairing harm. This may mean creating opportunities for those who have been harmed to share their experiences of past harms, and for those who have historically benefited from resources, unjust laws, and the displacement of others to listen, acknowledge the reality of those harmed, take action to repair the harm, and be accountable for doing whatever is necessary to ensure that harm will not be committed again.

Appreciation

To appreciate one another is to accept people as they are and to value different ways of being, knowing, and doing. People often come to networks with very different backgrounds, identities, experiences, and beliefs. A prerequisite to building trust between diverse groups is that diversity is recognized as a critical part of what makes networks thrive; after all, so much of the potential of network building comes from bridging connections across divides.

In practice, a culture of appreciation is one where many different styles and skills are valued and integrated. Deep trust is possible only when people are able to bring their whole selves to the network and contribute their gifts in whatever way they choose. To create a space where all participants are able to contribute fully, it is necessary to ensure that the dominant culture’s norms are not centered to the exclusion of others—in the United States, this means decentering whiteness such that other ways of being, knowing, and doing can flourish.

At an individual level, sharing appreciations also helps to get people out of their heads and into a heart-centered space, creating room for deeper connections to form. This is why we often have people offer appreciations at the end of a convening, asking them to reflect on “who or what are you appreciating right now?” Sharing appreciations in this way serves to reinforce the prosocial behaviors that the network wants to promote.

Trust creates a foundation of mutual respect upon which participants can hold whatever conversations they need to have to begin working together. In forming a community, we don’t build trust so that people will like each other or agree with each other. Rather, we build trust so that people can hold the tension through disagreement and conflict, find common ground, and work together to achieve mutual goals.

David Ehrlichman is a catalyst and coordinator of Converge, a network of practitioners who build and support impact networks. He is also author of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change and producer of the documentary Impact Networks: Creating Change in a Complex World. With his colleagues, he has helped form dozens of impact networks in a variety of fields, and was a founding coordinator for networks in the fields of environmental stewardship, economic mobility, urban revitalization, and Web3. He lives in the Pacific Northwest, finds serenity in music, and is completely mesmerized by his 10-month old daughter.

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

From Learning to Doing

Many years ago I was teaching high school English on a small island in SE Alaska. I asked the class to compare a piece of literature to the story of the Three Little Pigs. Half of the class couldn't do the assignment because they had never heard of the story of the Three Little Pigs. That changed me forever.

Without shared experiences, learning communities often talk past each other. Inevitably there is a judgement on one side or the other. Each learner brings his/her own experiences to a conversation and uses those unique experiences to make sense of things. Coming together as a learning community to sort through what we understood from something new that is introduced to us is sometimes very frustrating because of all the different experiences brought to the table. To help with that issue in almost any learning community, you can initiate a common experience/action for all participants. When an action is experienced together, suddenly there is more justice in the conversation. The playing field is leveled and the real conversation can begin.

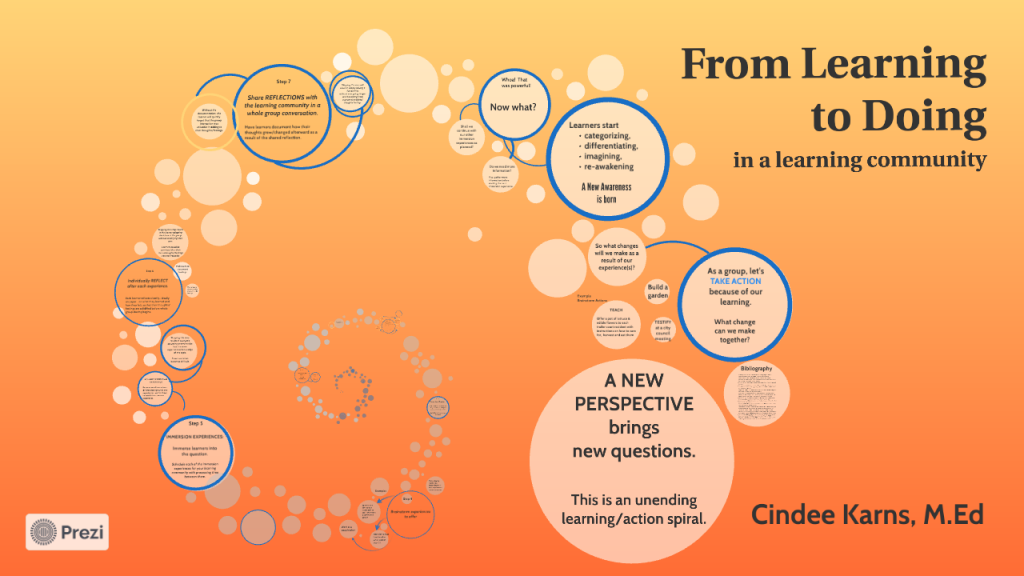

This is a depiction of how that process can be set up for any learning community. The condition is that the learning spiral never ends....every round goes higher, higher. The outcome is that participants almost always feel like they can act on their new knowledge and continue the learning cycle on their own.

Click HERE to access the "From Learning to Doing" resource. A slide presentation on how to create shared experience in a community to initiate actionable change.

Click HERE to access the slide show directly at prezi.com

Cindee Karns, a life-long Alaskan, is a retired middle school teacher with a master's in Experiential Learning. She is founder/weaver of the Anchor Gardens Network, which is attempting to bring increased food security to Anchorage. She and her husband live in and steward Alaska's only Bioshelter

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

The Angel's Mafia: elements to be addressed in peacebuilding governance

Our Better Angels need to get their act together.

I find myself looking back at five years working in peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Almost as long as I spent working as a mechanical engineer in the aerospace field. The business of designing and building spacecraft has one commonality with the “business” of building peace: they both involve people getting together and doing stuff. I used to be weary of the term peace-building as it implies the linear construction of something which can be described as an emergent property of a complex system. What is peace anyway? No, I’m not going down this rabbit hole now, but I leave the open question here for you to entertain yourself with.

You can’t really build peace the same way you build a Falcon 9 rocket. You can’t build the relationships between people the same way you build a clock but you can create the conditions for relationships to emerge, to strengthen and evolve. You can build the scaffolding that makes peace a more likely outcome than violent conflict. A Falcon 9 is just a very complicated clock. Peace is more like a cloud that emerges out of thin, moist air.

Back to my point: I left my engineering career in pursuit of a revelation. And that revelation has come back to haunt me, five years later.

Whether you’re building rockets or building peace, people have to come together and coordinate efforts to accomplish a Mission.

People have to get themselves organized. If it’s the rocket they’re building, the way of organizing is pretty straight forward. It’s a linear process. We’ve been building rockets for quite some time now and have learned a lot about how to do that efficiently. There are still some hiccups every now and then. When these happen, it’s up to the skills and mastery of the project manager (PM) and systems engineers (SE) to make sure they don’t compromise the Mission. The Mission is sacred. You may be an expert planner but as a PM, you’ll be judged by how creative you are when dealing with the hiccups: a delayed supplier, a volcano eruption, a failed test, a new requirement, a pandemic or a world war. The best PM’s I have met in my previous life were those that knew that you need to be ready to deal with contingencies and uncertainty. This is where a good governance system comes in handy. Running the day to day operation of an engineering team requires discipline, practice, expertise and structure. You’re inside a bubble of control. When this bubble bursts and the outside world comes barging in, you need something different. You’re operating in a different regime. The outside world is complex. Full of interconnections and invisible, mysterious forces. Enter the Law of Requisite Complexity which states that “In order to be efficaciously adaptive, the internal complexity of a system must match the external complexity it confronts.” And this was my revelation back in the day: management is different from governance! Management is all about the plan. Governance is about dealing with situations where the plan that you had is no longer the plan that is needed.

With the exception of perhaps the mafia or terrorist neworks, we don’t know how to organize in an enviroment of complexity and uncertainty. Since we enter kindergarten (and perhaps even earlier through models unconsciously passed on by our parents), we are conditioned to think that someone else, a parent, a teacher, a headmaster, a boss, a political leader, a country, a government, an institution, an NGO, you name it, must have The Answer. someone must have The Plan. Someone must have An Understanding of what is going on. Someone will manage it!

When faced with problems that, by definition, have no well defined problem-statement, no boundaries, no solution, we revert to this very rudimentary, almost medieval governance system where a few (typically old, white) men call the shots for all of us. I have nothing against old experienced men calling the shots sometimes (they may have some clever ideas), but I am against this being the only form of social organization in complex environments.

The peacebuilding world has taught me a lot about what it takes to thrive in a complex and ambiguous environment. If you survived a civil war and are engaged in local peacebuilding, you’re pretty much an expert in the Vuca World. I struggled to find my voice in this field. After all, what do I know about peace? I have never heard an AK47 fire.

I found my voice in the overarching theme of social organization and governance. When complexity and uncertainty (aka real life) bursts through your control bubble, that’s when investing in a governance system that obeys the law of requisite complexity makes it or breaks it. After five years witnessing the efforts of 24 South Sudanese Angels coming together for peace, here are a few elements I believe should be addressed when thinking about governance systems.

Communication, language and meetings

Communication is the essence of human social organization. For better and for worse, we’re doomed to use language to communicate and coordinate with one another. The pandemic zoom years have shown us that, while it is possible to keep in touch and even do management decisions remotely, there are times when a face to face meeting is unreplaceable. Whoever feels like a peloton bike is a full replacement of a regular bike has probably never experienced the bliss of a bike ride by the beach in a warm, spring morning.There are moments in the life of a peacebuilder when you literally need to see eye to eye. Feel the energy in the room, let your body speak and listen. There’s simply no virtual replacement for this. The same holds true for any team. There’s simply no replacement for a well facilitated face to face meeting when what’s at stake is the future of the Mission.

Non-violent communication, skillful facilitation of meetings, hosting space for convening, trust building and sharing, are all necessary groundworks for building a solid governance system. The groundwork needs to be in place and ritualized before going into the hard and messy part.

Sense-making, meaning-making, decision-making (SMDm)

What just happened?

If you’re convening a governance meeting, chances are, something happened. Because everyone on the team is so focused on his or her own subsystem, trying to draw a complete picture may be challenging. Typically, we jump too fast to conclusions here. This is where systems thinking comes into play. Every person in the room will contribute with his / her own perspective on the system and so it’s really important to facilitate a sense-making session that casts a wider, systemic lens on the issue. Whatever happened is the result of a system. Whether you’re aware of it or not, it’s 100% guaranteed that there’s an underlying system moving the pieces. The aim of this sense-making session is to flesh out the elements of this system and move to the next phase of the discussion by asking “What does this mean for the Mission?”

For the engineer working on Falcon 9, it’s relatively straightforward to answer this question. It may take some research, modeling and forecasting but it should be possible to figure out what a delay in the delivery of a component means for the whole mission. Remember, it’s just a very complicated clock, not a cloud.

This is not the case for peacebuilding. The meaning of whatever just happened is deeply related to your own individual meaning making structures and how it is shared with the collective. Collective meaning making in social complex systems is impossible to do without some agreement of what reality is. Without this agreement (or “epistemic commons” if you will) how do we know what we know about the social reality and how do we co-create a shared social imaginary? You need to have a shared dream or shared goal to work towards. Without this shared dreamland, collective meaning making becomes impossible.

If sense and meaning are shared (easier said than done), proposition crafting and refinement should easily flow out of the previous steps. What?, So What?, Now What? This is the way many Western philanthropies and organizations talk about learning and adapting “and governance” itself is a very Western word with all sorts of unintended connotations. However, this is a universal human concept. Every culture has a way of making decisions. We in the Global North tend to sometimes forget that every day all over the world, people in communities come together to come up with proposals to solve problems. Working in smaller teams or networks could prove to be extremely creative and effective if it is coupled with a decision making process, such as consent decision making to fast track good ideas into actionable prototypes and have a basic foundation for what to do when you do not agree or the plan goes sideways.

Finally, the governance process should answer two cornerstone questions: accountability and legitimacy. Whatever comes out of the process must be accompanied by a clear statement of accountability (who has skin in the game?) and legitimacy. In Western contexts, charters, MoU, constitutions, manuals, contracts, can play a role here. But these can overcomplicate the real work. What I have found in my time in peacebuilding is that the deepening of relationships and agreement for action can start with three questions. What do we want to do together? How will we make decisions? What do we do when we don’t agree? In short, how do we want to show up together? This is one area where I think there’s a lot to innovate in civil society movements. Peacebuilders can learn from movement activists how to set the foundation for adapting quickly while keeping a focus on the desired goal.

Organizing for Peace

Kurt Vonnegut knew it: “There is no reason why good cannot triumph as often as evil. The triumph of anything is a matter of organization. If there are such things as angels, I hope that they are organized along the lines of the Mafia.”

I believe that our perennial mission is to organize. We do that so elegantly with clock problems. Now it’s time to complement that toolset with other rituals that help us organize around cloud problems, too. I hope Pinker’s Better Angels take a lesson or two from the Mafia, but outrage or hope alone won’t cut it. I believe there’s a lot to be done to help peacebuilders around the world get organized in a way which creates, not a rigid, but an emergent order that is able to sense and respond to the challenges posed by the destructive forces of violence and war.

Pedro Portela is the Founder of the Hivemind Institute, a think tank and action research organization in Portugal dedicated exclusively to prototype new models of local organization, advocating for more systems literacy and proposing networked approaches to complex social problems.

Originally published at The HiveMind

featured image found HERE

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources?

Donate below or click here

thank you!

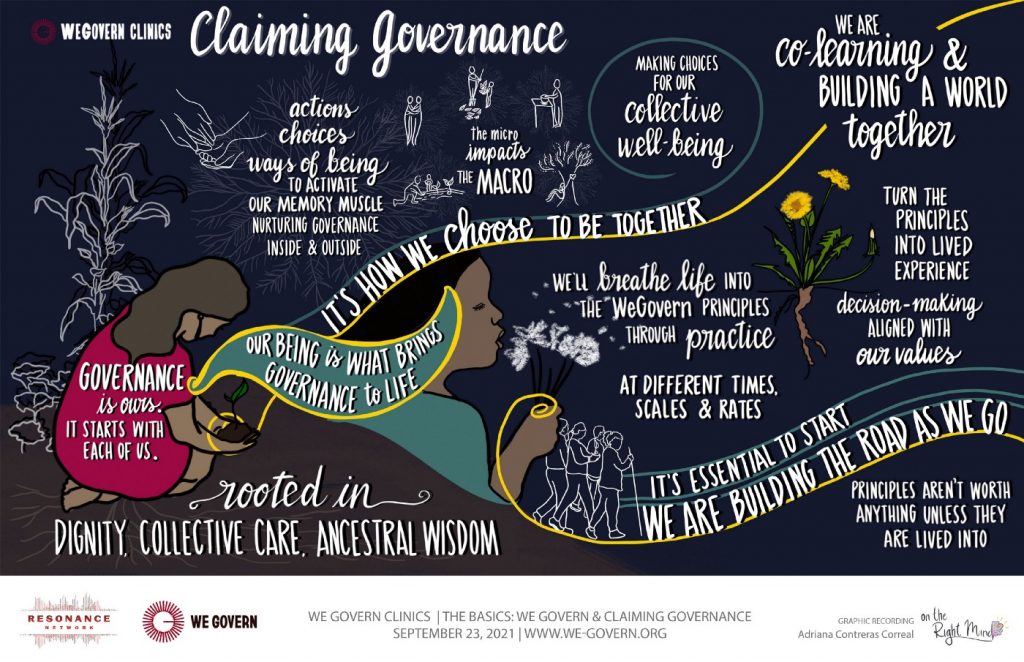

Governance is how we choose to be together

An illustrated story of liberatory governance practice

Storytelling — like governance — can take many forms.

When choosing new ways of being together, we begin with ourselves — in our bodies, hearts, spirits. The choice to be in governance rooted in mutual care is an embodied one. Once it rests within us, the practice begins.

Accordingly, the story of governance practice is a multi-sensory one. It takes shape in the colors, textures, voices, sounds, and sensations of our beloved communities — it is multi-dimensional.

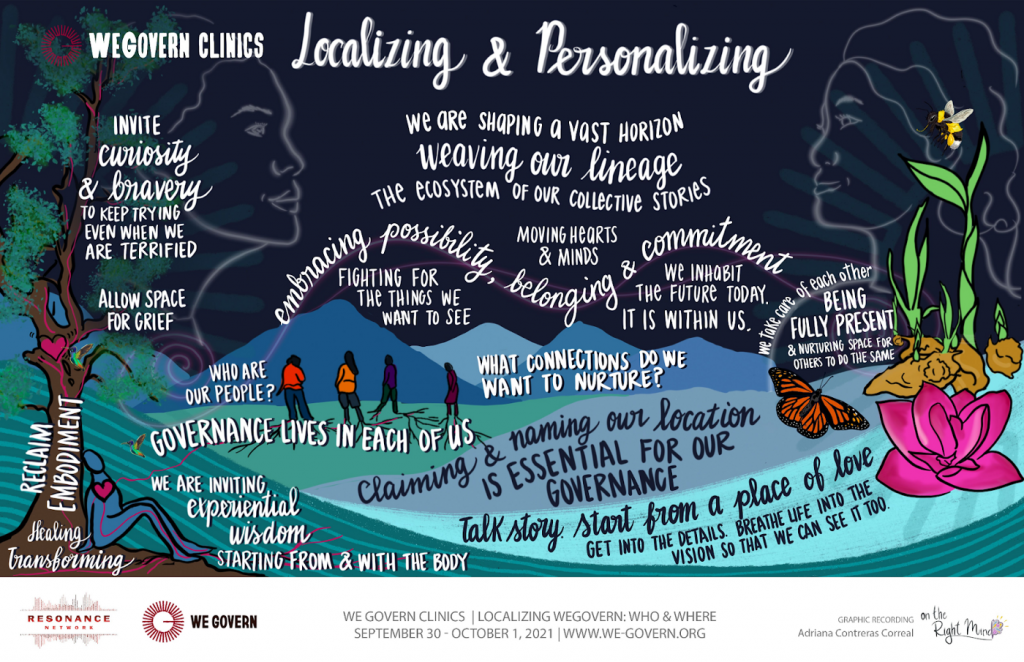

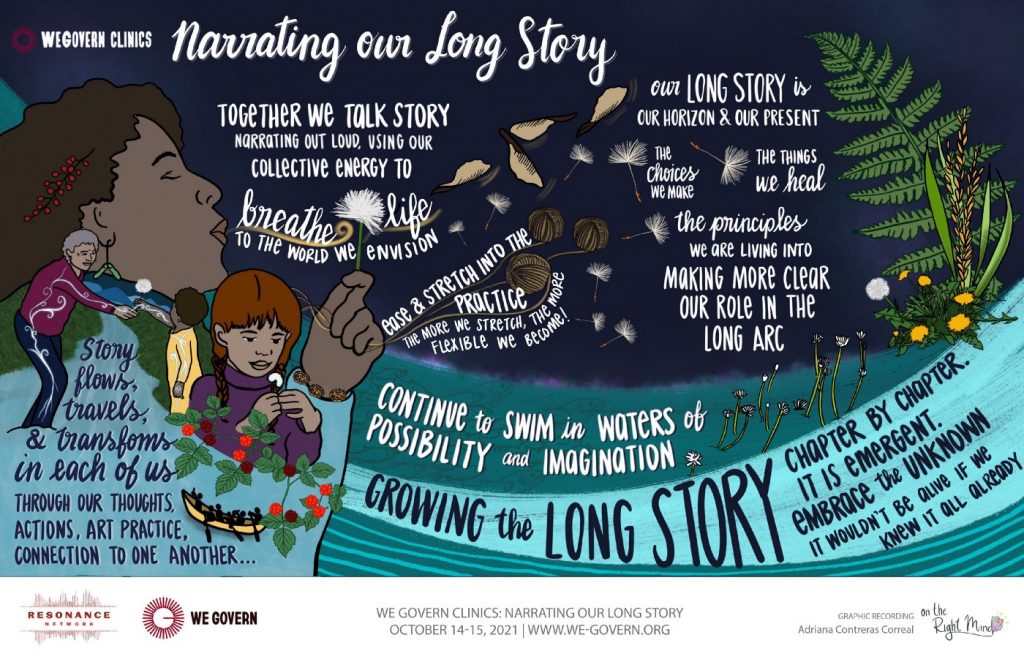

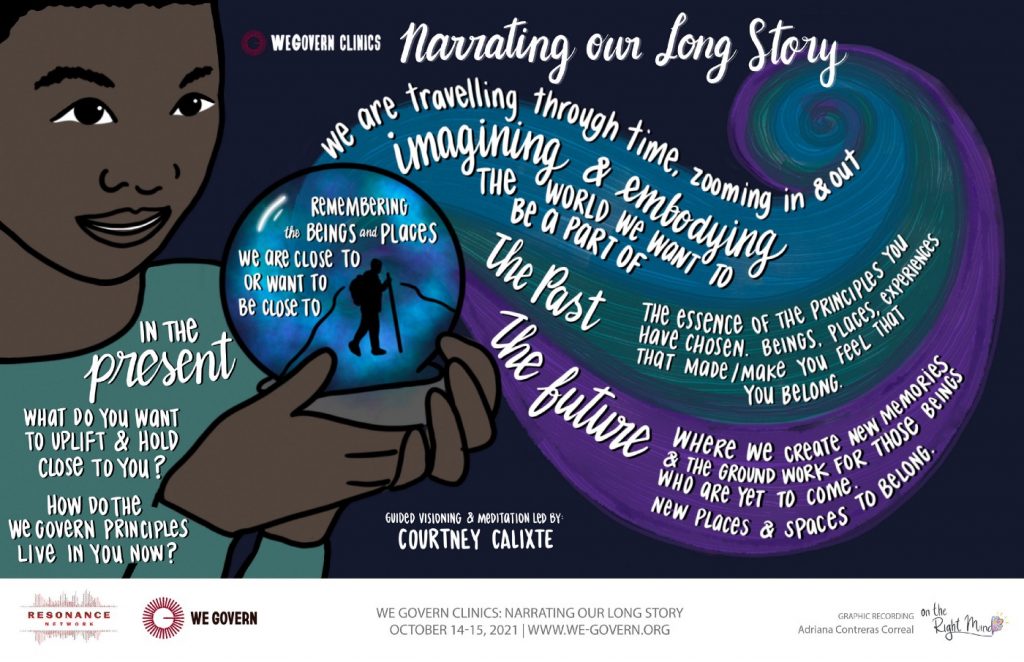

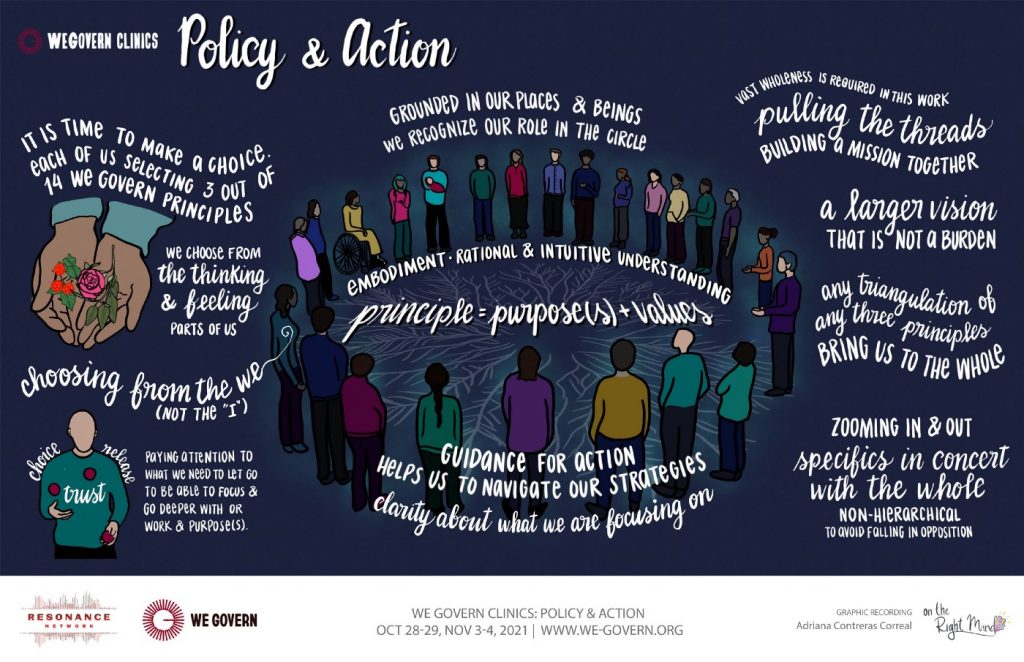

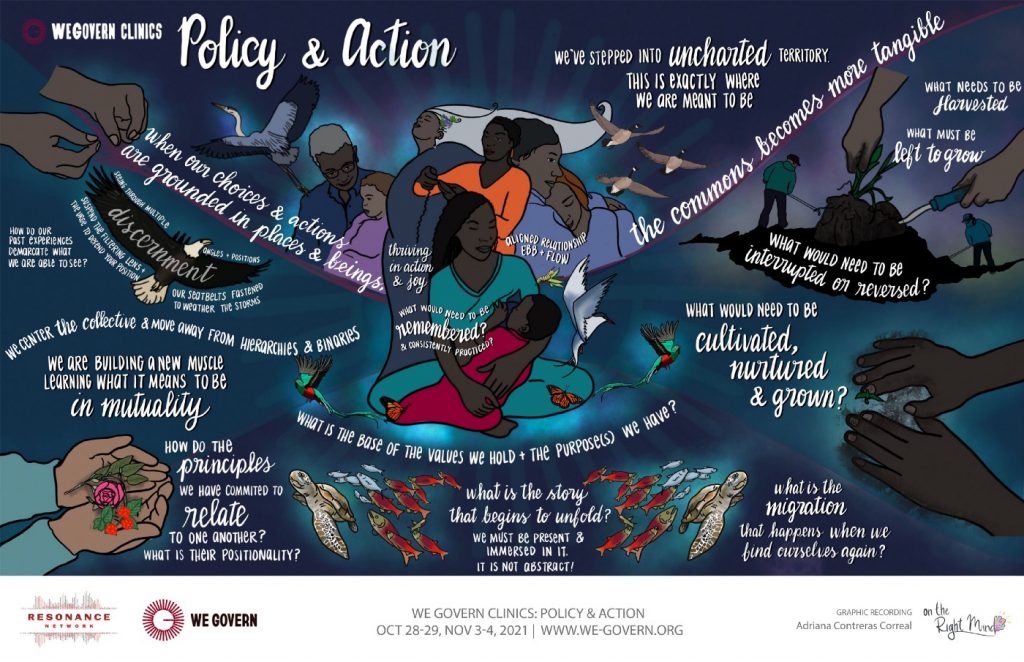

Last year, a group of worldbuilders came together with a shared commitment to collective liberation — and the governance principles we’ll need to bring it into being. Together, we moved through a series of clinics to deepen our collective governance practice.

What follows is a constellation of words, images, and musical offerings to describe this journey into liberatory governance. These images are the work of our beloved Adriana Contreras Correal of On the Right Mind. Deep gratitude to Adriana for sharing her gifts with us.

We invite you to enjoy our practice playlist and delve into the story below…

Collective governance begins with a choice: to commit to the ways of being that enable all beings to thrive:

Transformation begins when it’s personal: once we’ve committed to collective governance, we begin by grounding in place. Our work begins at home:

As our practice takes root, we continue illuminating the path toward what is possible, by narrating our visions for our communities into story:

Holding close to our stories of liberatory futures, we focus in on policies and actions we will need to sustain a world beyond violence — a world where all beings can thrive:

Originally published at Reverb

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

MAKING LARGE EVENTS PARTICIPATORY

This blog was originally published in October, 2019, when we couldn’t foresee that most large events would cease. As we anticipate meeting again in person, I hope the approaches here give you ideas. You might like to check out my new meeting design coaching services.

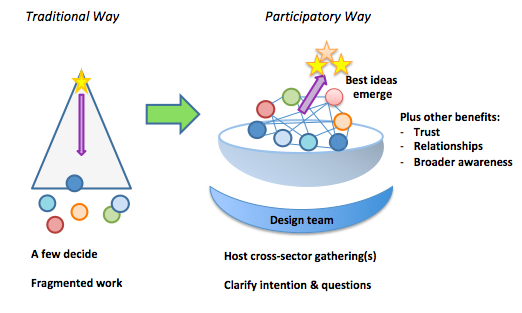

It’s possible to make large events participatory and interactive. Here we share our latest inspiration and approaches, from recent work with events from 50 people to over 200 people. The topics and audiences vary, yet the desire to inspire and connect people, enhance learning, build connections, and advance work beyond the meeting is the same. Here’s what goes into our secret sauce for creating a participatory, inspiring event:

Participation starts in design: Working with a design team that includes representatives of the people who will be participating in the event helps ensure the event format is relevant and effective. This group can:

- Bring varied perspectives to clarify the context and conversations that are needed now. For example, with a state-wide food network that’s been underway for five years, we landed on this strategic question: How can the structure and approaches of the network galvanize and support action and momentum at the local, regional, and state levels? It took some thinking and conversation to get clear that this was the most powerful question for this moment. We brought in case studies to spark the conversations.

- Provide input on the format of the meeting and who to invite and how, e.g., you can access the broader social and professional networks of those in the room to learn about other people, organizations, and initiatives who could be invited.

- Serve as ambassadors for the vision and the meeting/initiative, spreading the word, helping with invitations, and sharing feedback they are hearing.

For example, we co-facilitated the annual meeting of the Greater Nashua Public Health Network, with a focus on building a trauma-informed community. The design team helped us get a sense of how much training had been done so we could tailor the content of the training portions. We agreed on a clear set of desired outcomes and went through several rounds of an agenda design, tailoring and improving it each time, based on their feedback.

At the event, start with stories: Getting people sharing stories early in the day builds relationships and creates a warm, welcoming environment. Our approach is inspired by an exercise called Radical Acceptance, which I learned from taking improv classes with Boynton Improv Education in Portsmouth, NH. This simple exercise builds a sense of emotional safety and encouragement for everyone to speak up. I modified it slightly by doing the following:

- At round tables, invite each person to introduce themselves and share one brief story of something going well in their work. Invite everyone to respond with a “yes!” or any other enthusiastic positive response. Then the next person goes and the group does the same. Across the room you hear “yes!” and clapping and laughter, and see fist bumps.

- In another variation at the Nashua meeting, we asked each person to share one thing they appreciate about Nashua/the region and put it on a post it note. We used the same process I mentioned and then collected these and had a graphic facilitator make a poster of the themes.

This only takes 10-15 minutes. Sometimes people pick up on the “yes!” and bring that positive response into other parts of the day, often with a shared laugh.

Offer inspiration/new ideas and new voices: Beyond the standard keynote presentations and skill-building workshops, consider having shorter TED-talk type or PechaKucha presentations (presenter has about 7 minutes to talk with 20 image slides) and featuring voices beyond “experts,” e.g., youth, those with lived experience, people from marginalized identities or communities.

Host cross-pollinating small group conversations: The World Café process taps the ideas of everyone in the room and allows people to make new connections and learn from each other. At an anti-racism gathering of 200+ people from Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, we invited people to talk in a group of four with people from their state about what is working in anti-racism work. In the second round, they mixed to a new group of four with people from other states, sharing themes from the previous conversation, and then talking about what more was needed. With 200 people, this meant we had 50 four-person conversations each round (100 total), which is a lot of learning and information exchange…and fertile ground for new relationships and collaborations to form.

Allow space for self-organized deeper dive conversations: All of the conversations and ideas percolating through the first part of an event can be given a space to land and deepen if you design space for that. Inspired by the process of Open Space, here’s an example of how we organized this at the event with 200 people:

- During the morning sessions, we asked people to submit topics they’d like to discuss with others at an Open Space/deeper dive conversation session that afternoon.

- Over lunch, we grouped these into about 16 overall topics. I made folded table tents with a table number and name of the topic and put these out on the round tables. I sketched a chart showing table numbers and topics, took a photo, and put it up on a slide.

- When that session began, I invited people to join the topic they’d like to discuss and walked around with a roving microphone to introduce the topics and show which table was where, with the slide image as another guide.

- We asked for a note-taker at each table. For topics where lots of people showed up, we invited them to split into several tables. At the end, we heard brief highlights from the table conversations.

At another event, we had time for people to rotate to a second topic table, while some people stayed at the first one, building in another layer of connection and cross-pollinating.

The range of topics that were suggested were far beyond what our design team would have thought of, and we learned which areas had the most interest. People had the freedom to initiate or join conversations and connect with others with similar ideas, concerns, and questions.

I wish I could somehow visualize and learn all the seeds that got planted at these events. We offered the fertile ground – so time will tell what grows!

Beth Tener is a leadership trainer and coach who helps social change leaders live their values as they address complex challenges, such as transitioning to a clean energy economy, disrupting racism, and revitalizing communities. She is passionate about bringing people together in ways that unlock and ignite personal, group, and community potential. She is the founder of New Directions Collaborative, based in Portsmouth, NH, and has worked with over 200 organizations and collaborative networks.

originally published at New Directive Collaborative

featured image found here

Adapting a network’s theory of change

Collective Mind hosts regular Community Conversations with our global learning community. These sessions create space for network professionals to connect, share experiences, and cultivate solutions to common problems experienced by networks.

On September 22nd, 2021 we met with Carri Munn from Context for Action and Amelia Pape from Converge for our first Community Conversation of the fall. Carri and Amelia shared their experiences collaborating with network teams to adapt Converge’s theory of change to their networks and the process and successes of co-creating a shared theory of change with network leaders.

Highlights from the conversation

Complex problems are by nature nonlinear and typically must be addressed from many angles at once. This is why networks, in their ability to connect and facilitate collective action between people and organizations, can be successful and impactful in creating system change in complex environments. As defined by our co-hosts, a theory of change describes how a network can create systemic change by harnessing the interdependence of the network system – its members.

The way networks create system change – or their theory of change — can often emerge in phases. The conversation outlined these phases, beginning with connecting the actors within the network system, working towards building trusting relationships and an understanding of members’ contexts. This is the foundation necessary to reach the coordination phase, when regular communication and coordination starts to occur between people within the network, people are supporting the work and each other, silos are starting to break down, and information, value, and learnings begin to flow from the connections that have been created. From here, the collaboration phase emerges and members begin to recognize a shared purpose within the larger system and opportunities to collaborate within it. It is these emergent collaborations that begin to create and perpetuate more and new collaborations and, eventually, system change and impact at scale.

This phased framework is a way to talk broadly about a network’s theory of change. However, network leaders often need a specific and contextual theory of change to effectively communicate to and strengthen the network. Our co-hosts shared an example of using this framework to support a network interested in transforming a broad theory of change to one that represented their network’s specific activities, as a means to communicate and collaborate more effectively with its members and stakeholders.

Using the phased theory of change framework — connection, coordination, and collaboration — our co-hosts described their process, which started with using surveys and conversations to gather information from the network about the challenges, barriers, and opportunities that existed within the network system in its current state, and to describe the optimal system impact, or the realized vision, they hoped to achieve. These became inputs for a virtual Mural storyboard session where they facilitated a smaller group of network participants to articulate what they hoped to create and achieve in each phase and how they viewed their roles and relationships within these phases. The storyboarding exercise was a way to help the network articulate how they would create the conditions for impact and collaboration to emerge that would be considered those of a healthy network and then use those outcomes as a tool to communicate with and bond the network.

What also emerged from this conversation was the critical role of network coordinators in theory of change processes. Coordinators are often the catalyst in orienting networks to see the bigger picture. As facilitators of a complex system, it often falls to them both, by necessity and design, to engage members in conversations about how they see themselves as part of a larger whole and how to contribute to transformational change in the network system.

Miss the session? View the recording here.

Sign up for the Collective Mind newsletter to receive these in your inbox!

Thanks again to our co-hosts, Carri Munn and Amelia Pape!

Get involved

Have your own experiences developing a theory of change? Tell us about it in the comments below.

Join us for the next Community Conversation!

Or email Seema at seema@collectivemindglobal.org to co-host an upcoming session with us.

original article published HERE

Experimenting Towards Liberated Governance

Over a year ago, Vu Le published an article about the current models for nonprofit boards. The title “The default nonprofit board model is archaic and toxic; let’s try some new models” doesn’t bury the lede. Of the current models, Le writes:

“Over the years, we have developed a learned helplessness, thinking that this model is the only one we have. So we put up with it, grumbling to our colleagues and working to mitigate our challenges, for instance figuring out ways to bring good board members on to neutralize bad ones or having more trainings or meetings to increase ‘board engagement.’”

At Change Elemental, we have been experimenting with some new governance models, informed by the work of our clients, partners, and many others in the field who are trying out new structures and ways of governing. For example, Vanessa LeBourdais at DreamRider Productions has shared principles and practices of “evolutionary governance”, and Tracy Kunkler at Circle Forward has supported our learning about consent-based decision making. Countless other groups who have continued to uphold and practice historic, ancestral, Indigenous, and intergenerational structures of governance—and have informed these other values-aligned governance models—have catalyzed our learning.

Here, we offer a specific window on the evolution of our board, including some practices we’ve dreamed up, borrowed, and re-remembered to align governance with our values in a nonprofit system set up to default to white supremacy, paternalism, power over, and other oppressive habits.

The following questions have formed the basis of our governance and leadership evolution (we’ve shared more about our leadership evolution in recent blog posts here and here):

- How might we realize deep equity and liberation in leadership and governance?

- How might we evolve leadership and governance structures to share power and work in more networked ways?

- How might we align leadership and governance practices and culture with our values?

Our journey began a few years ago when our board and core staff team began to get curious about what it might look like to think about our board as mycelium. Mycelium are fungal networks that spread across great distances within soil (and sometimes underwater) and process nutrients from the environment to catalyze plant growth, supporting ecosystems to thrive. In our context, we use mycelium to refer to the powerful network of tendrils and roots that connect our board and core team to other people, groups, and organizations, enabling us to turn toxins into nutrients and nourish ourselves through our relationships to ensure collective thriving and care.

Here is what we’ve learned so far in our governance evolution (from the core team perspective—more from our governance team coming soon!):

Shifting language from “board” to “governance team” helped us reframe the governance team’s role.

Early on we shifted from referring to our board as “a board of directors” to a “governance team.” Tracy Kunkler of Circle Forward offered this definition in a small group experiment on governance we facilitated:

“Every culture (in a family, a business, etc.) produces governance — the processes of interaction and decision-making and the systems by which decisions are implemented. Governance is how we set up systems to live our values, and leads to the creation, reinforcement, or reproduction of social norms and institutions. Governance systems give form to the culture’s power relationships. It becomes the rules for who makes the rules and how.”

Shifting language supported us to shift our mindsets about governance. This language guided us towards greater clarity about our own governance team’s role: co-creating systems and practices that can support and catalyze us to live our values. It also deeply shifted how we both hold and reimagine the boundaries between the 12 people on our governance team, our core team (staff), and other partners to be more porous and center collaboration, emergence, and our interconnectedness.

However, because shifting mindsets requires shifting patterns and practice, this switch in language isn’t simple. We have noticed that we sometimes revert to using the term “board” rather than “governance team” when we are talking about potential barriers that the board may present or “traditional” board responsibilities such as fiduciary oversight. This is a work in progress and when we find ourselves reverting to old language, it is a signal that we might be in older practices, patterns, or ways of thinking about our relationship to the governance team and its role that are no longer serving us or our work.

Practicing liberatory governance is having one foot on land and one in the sea.

Getting clearer on our governance team’s role deepened our sense of what it might look like to realize deep equity and liberation in governance. We began to understand what “liberatory governance” could look like for us—a governance team that partners with us to bridge between current reality and the future we’re building by: moving the organization towards greater alignment with our values; and co-creating liberatory systems and ways of working together that can transform the larger oppressive systems we’re operating within. We talk about this internally as “having one foot on land and one on water,” a metaphor Hub member Elissa Sloan Perry shared from Alexis Pauline Gumbs. Gumbs hears best with “one foot in the water, one foot in the sand.”

In our organizational context, the “water foot” attends to things like our vision, uninhibited aspirations, values alignment, and acting today in ways that prefigure the world we want to see. The “foot on land” takes into account the world as it is, such as the requirements and legal constraints of our 501.c.3 tax designation, and current financial realities and access to other resources, where trust-based relationships can sometimes become transactional or even litigious. Our governance model values both “feet” in its awareness and decision-making. When we make decisions, the “water foot” leads with the “land foot” as a valued, supporting, and crucial partner.

Creating multiple, fluid points of connection across the staff and governance team helps build the relationships and trust necessary for shared leadership and power.

Building trust and mutual accountability are at the heart of our evolving governance structures and practices, just as we have found it to be in building toward shared power and leadership at the staff level. This work is more time-consuming than conventional governance models so we needed to build our collective capacity for sensing what is actually too much time. We also needed to strengthen our skill and capacity for generative conflict including discerning when to: enter into conflict and tension; sit with it so that we can reflect and discuss later; and/or intentionally let it go. This has meant getting more comfortable with sitting in discomfort when conflict can’t (or shouldn’t) be resolved immediately.

Some simple structures and systems support us in developing these capacities and discerning what is needed to build trust and move through conflict. For example, we wanted more interaction between our core team (staff) and the governance team, but didn’t want to necessarily add more large group meetings—we wanted connections to be deep and purposeful. To create purposeful connections, where a broad range of staff and governance team members could develop relationships and bring their unique gifts, we opted to have governance team co-chairs work with a staff liaison. The staff liaison partners with different staff, bringing different people into conversations with the co-chairs and other governance team members where their experience, wisdom, and gifts are critical. The co-chairs and other governance team members then connect together and separately into different areas of work based on their interests, skills, and what is needed.

We also evolved our governance team meeting structure to have staff members join for key sections of the meeting. We share the agenda in advance and offer some guidance to help staff decide when they might join or when they might opt out of a meeting. Additionally, staff and governance team members now caucus separately at the end of each governance team meeting to debrief and raise unresolved issues with the intention of sharing back what needs the full group’s attention. The caucuses support greater truth-telling across the governance team and core team, deepen our understanding of each other’s perspectives and help us dig into conflict with love and rigor.

Grounding in shared values is critical for practicing liberatory governance.

If you were to review the specifics of our governance team’s role, you might not find anything surprising or “new.” The difference is in how the governance team carries out these responsibilities – with a rooting in shared values with staff and commitment to working through differences in values when they show up.

In recruiting and engaging governance team members, we haven’t just sought out individuals who conceptually agree with our values (which were reflected in our recruitment criteria), but people who are game to experiment on what it looks like to make decisions rooted in those values. People who already embrace and practice inner work, multiple ways of knowing, experimentation, and emergent strategy—and who are looking to upend traditional governance team models and create and remember anew.

Even with the perfect container, structure, and systems, it’s the people who make up our core team (our staff) and governance team – their own values as well as their willingness to be in the generative tension that helps support shared values – who have accelerated our work in shared power and leadership both on the core and governance teams. Together, we are living into our vision and deepening our practices of shared leadership and shared power to shift conditions towards love, dignity, and justice.

Look out for more learning from these experiments in liberatory governance in the new year!

Natalie Bamdad (she/her/hers), joined Change Elemental in 2017. She is a queer and first-gen Arab-Iranian Jew, whose people are from Basra and Tehran. She is a DC-based facilitator and rabble-rouser working to strengthen leadership, organizations, and movement networks working towards racial equity and liberation of people and planet.

Mark Leach (he/him/his) has over thirty years of experience as a researcher and management consultant. Mark has a particular interest in strategy, leadership development and transition, and issues of equity and inclusion in organizations.

Originally published at Change Elemental

Banner Photo Credit: Kirill Ignatyev | Flickr

The Art of Measuring Change

What are your associations with words such as “measurement”, “evaluation” or “indicator”? For many people these words sound annoying at best, and there are good reasons for it. Yet - given the fact that you clicked on this article - it’s also very likely that you are motivated to contribute to social change, and the main intention of this article is to share about the beauty and collaborative power of attempting to measure it. What I am not doing is offering quick solutions, the same way art is not a solution to a problem. Rather, it is an invitation to step back, look at the nuanced process of change with curiosity and an inquisitive mind, and maybe discover something new. The article is also available as a dynamical systems map.

In a nutshell

There are two ways of reading this article:

- Exploration mode: Use the systems map provided above and use the visual representation to navigate through the article more flexibly.

- Focussed mode: Stay here and follow the flow of the article.

Here already a quick overview of the main points and arguments:

- There is a good reason to be skeptical of impact measurement. If the approach taken is too simplistic and/or mainly serves to validate a perspective (e.g. of the donor), it’s almost impossible to measure what truly matters. Rather, such an approach further perpetuates existing power imbalances and puts beneficiaries at risk. (section: The dangers of linearity)

- The measurement of social phenomena has to pay justice to the intricacies and complexities of a project, a program, or any given action. This requires understanding, which puts empathy, listening and collaboration at the centre of an empowering approach to measuring change. (section: About potluck dinners and “power with”)

- Meaningful indicators serve as building blocks in the attempt to capture social change. An indicator is meaningful when it not only follows the SMART principles, but is also systemic and relevant, shared (understood and supported by all stakeholders) and inclusive (aware of power relationships). (section: Indicators that matter)

- Complexity science can provide an alternative scientific paradigm to understand and make sense of our world and, hence, to measure change. (section: Coming back to complexity)

- It’s time to equally distribute power, namely the ability to influence and shape “the rules of the game”, or potentially even the kind of game that is being played in the first place. A crucial step towards this is describing and defining what desired social change is and how we go about measuring it in a collaborative way. (section: Synthesis)

The starting point

I have been working in the field of impact evaluation and measuring social change for around 6 years now. I’ve interviewed cocoa farmers in Ghana, developed surveys and frameworks, crunched Excel tables of different sizes and qualities, mapped indicators, and held workshops on tracking change in networks. Doing all of this is way more than a job to me. I have met wonderful people on this path, have been part of impactful projects and really had the feeling of being able to contribute in a meaningful way.