Building Communities Through Network Weaving

In 2004, Valdis Krebs and I collaborated on an article that described the stages of network development and introduced the term network weaver.

In 2005 an edited version of this paper was included in the Nonprofit Quarterly.

This article is newly added to our RESOURCES page... and it's FREE!

To download CLICK HERE

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Foodshed team learns how to establish consent instead of consensus

In Propositions for Organizing with Complexity: Learnings from the Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP), Nikki D’Adamo-Damery described nine propositions that emerged from the work of the AFP. Proposition #2 was: “Establish Consent instead of Consensus.” The following story describes one of the experiences we had together, when Tracy was facilitating the management team, that led to this proposition.

This story begins when the AFP management team was making decisions about how they were going to award mini-grants to on-the-ground projects that addressed community food security. The team included the principal investigators, graduate students, extension agents, and representatives from community-based organizations, and so reflected some of the diversity of the system within which they were working. The team was using a collaborative decision-making framework, and the basis for decisions was the principle of consent.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

The principle of consent

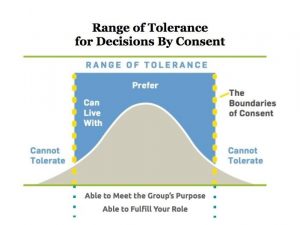

People often think there are only two choices for how we make governance decisions: by majority or consensus. Most people fail to realize that decision-makers have a third option – decision-making by consent – that can be preferable to either of these for governance decisions. The Consent Principle means that a decision has been made when no member of the group has a significant objection to it, or when no one can identify a risk the group cannot afford to take. In other words, the proposal is not out of their Range of Tolerance (see below). Those risks are things that would undermine the purpose, or that would create conditions that would make it very difficult for a member to perform his or her role.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

The test for the management team

The urgency to get the funds out into the field put pressure on the team to make a decision. On the one hand, there was clear value in having these different perspectives at the table as they discussed funding priorities and how to make the application process more accessible. On the other hand, there were conflicting opinions when it came to designing the application. Was it ethical for representatives from community agencies who might apply for the grant funds, to design the actual application? A professor said “no” and a community agency rep said “yes.” There were concerns that the difference of opinion might limit progress.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Consent is grounded in dialogue, not debate

It was through this experience that they learned that, by using consent as the basis for decisions, the team did not have to agree. Instead of debating, they inquired into what was out of the range of tolerance for each of them. They listened to each other’s objections as feedback about potential risks so they could adjust the solution to mitigate those deemed unacceptable.

Here’s what they discovered:

- The professor was actually concerned that there might be a perception about a conflict of interest if the community partners applying for awards were involved in the design of the application questions. That perception was the risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the project’s credibility and trust in the community.

- The non-profit director was concerned about the integrity of inviting community reps into the decision-making process, and then withholding that power when issues got sticky. That power dynamic was a risk the project could not afford to take — because it would undermine the trust within the core team.

Once they discerned the reasons for concern – and chose to respect what was important to each of them – they found a way forward. The decision was to include the community partners in decisions about the application design, as full decision-makers, AND to be fully transparent in all public communications about their participation. As a side note, they were simultaneously clear that, if one of those community-based organizations applied for a grant, they would recuse themselves in the selection of grant recipients.

The grant application design and process went mostly smoothly with no conflict of interest issues. The second round of distribution of mini-grants moved even more quickly, building on the trust that had been built the first time around.

This blog post originally ran on the Virginia Cooperative Extension: Community, Local, and Regional Food Systems blog. and at CircleForward.us

*The Appalachian Foodshed Project (AFP) originated in 2011 as a grant funded through the USDA’s Agriculture, Food and Research Initiative (AFRI) grants program (Award Number: 2011-68004-30079). Virginia Tech served as the lead academic institution in partnership with North Carolina State University and West Virginia University for a five-year endeavor to address community food security in western North Carolina, southwest Virginia, and West Virginia.

By Tracy Kunkler, MS – Social Work, professional facilitator, planning consultant, and principal at http://www.circleforward.us/[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Please post any thoughts, comments or stories in the comments section below.

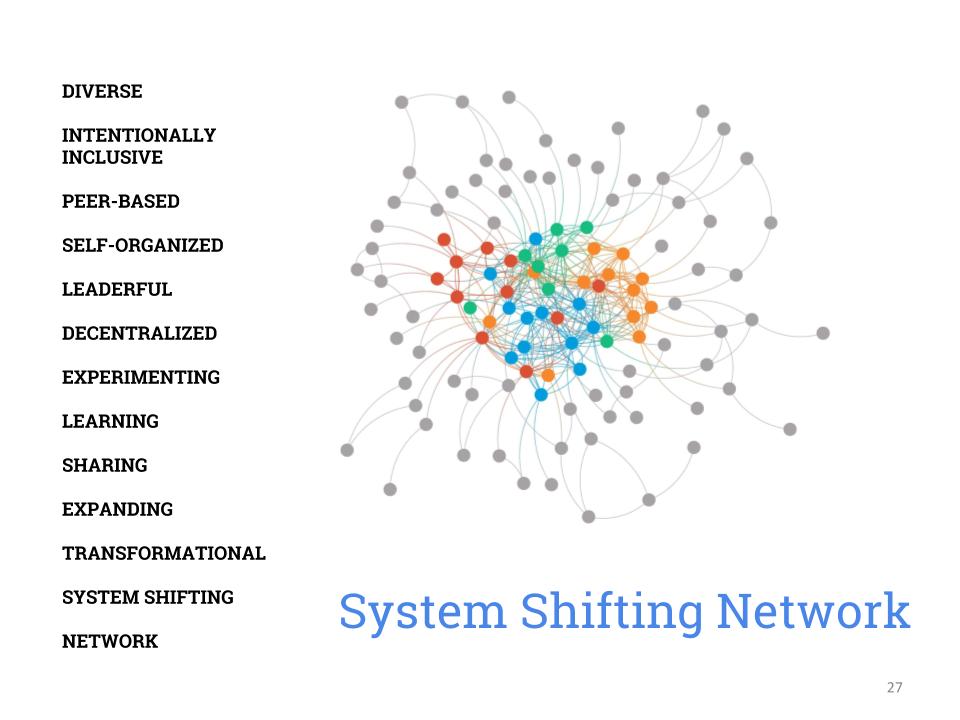

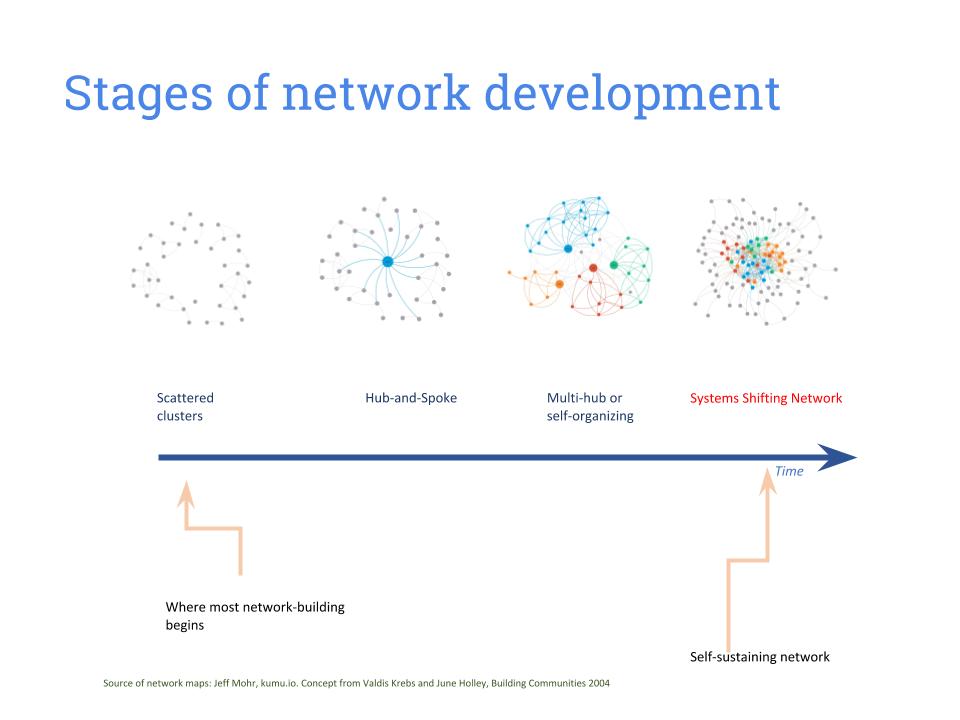

System Shifting Networks

Not all networks are the same! If you are interested in transforming systems so that they are good for everyone, then you are probably helping people co-create a System Shifting Network.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]If you are not familiar with network maps, here is a short guide: [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The circles represent individuals.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The colors represent diversity - you can make maps that show geography, type of organization the individual is part of, race/ethnicity, interests, etc.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The lines represent relationships. You can draw maps where the lines represent different relationships: that the individuals know each other, have worked with each other, or want to work with each other.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The network has a substantial core or center of diverse individuals who know each other or are only a few steps away from others.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- The grey dots represent people in the periphery, that is, only one or two people know that individual. People in the periphery are often resource people that can be drawn on as needed, or people from other networks. The periphery should have 3-5 times the number of people in the core.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]Here’s what makes a System Shifting Network more powerful in creating change than most types of networks. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Groups of people in System Shifting Networks (SSN's) are continually forming new collaborations to try to learn more about the system they are disrupting and the system they are shifting to. Often SSNs have dozens or even hundreds of these collaborative projects underway at any one time, and many people are in more than one project. Because of this overlap, innovations generated in one collaboration often quickly spread to many other collaborations. Think, for example, about the way the use of zoom.us videoconferencing has spread among people in networks.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- People in System Shifting Networks are continually bringing new people, especially those often under-represented, into their collaborations. These individuals often bring in new perspectives and make people challenge their assumptions, often resulting in much more effective projects.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- In these collaborative projects, people have to scramble to develop new skills and learn new ways of working together. People in these collaboratives work as peers, even though they may identify a coordinator. Everyone in the project learns how to organize and implement a project, and thus there are plenty of new network leaders capable to initiate new projects. So leadership is continually expanding. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- Projects are seen as experiments - a way to get more insight into the system they are shifting. They learn what works and do more of it.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

- People in projects take time to share what they are learning with others in the network and in other networks so that everyone benefits from every project, whether it was a “failure” or a success.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]But how do we develop System Shifting Networks? Most networks go through 4 stages: [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

STAGE 1: Many networks start as scattered clusters among individuals. Often the relationships in these clusters are informal - people talk to each other in the grocery store and at their child’s soccer game .[ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

STAGE 2: Then some individual, organization or group decides to start the formation of an intentional network focused on a particular issue, problem, sector or geography. They become a network hub. They reach out to others they know are interested in the issue and find out about their needs and interests. Often networks stay in this stage, and the hub broadcasts useful information to the interested individuals and has conferences and webinars so network participants can gain new information. However, if a network stays at this stage it loses many of the advantages of networks and will not be capable of changing a system.

STAGE 3: The next stage moves the network to a self-organizing phase. With a lot of support (which we will go into in detail about in future blog posts), individuals or groups in the network start noticing some action that might make a difference and form a collaborative project. Sometimes a network does a system analysis and identifies leverage points and forms working groups to generate experiments in that area. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

STAGE 4: The final stage - a System Shifting Network - emerges when a substantial support structure - communications, learning, restructured money and resources and just-in-time tracking shared with participants - is developed. Projects get larger and have more impact.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]What stage is your network? Please share in the comments section below.

Welcome to the Network Weaving Blog

There are over 1.4 million tax-exempt non-profits in the United States, many of them working on the hard-to-shift systemic problems of our society, such as racism, poverty, immigrant rights, access to food and healthcare, inequitable education systems, and climate change.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]Systems change and networks

But many of those organizations have realized these problems are extraordinarily complex. Solving these problems requires shifting entire systems, something that is not possible for a single organization to accomplish.

We are seeing a rapid increase in the number of networks forming to work on problems collaboratively.

As a result, we are seeing a rapid increase in the number of networks forming to work on problems collaboratively. Many of these are having truly impressive results:

Increasing local food access and sustainability through networked policy councils

Increasing access to healthcare

Stopping new coal-fired power plants in the Midwest

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]Network Practice is underdeveloped

The problem, as I see it, is that the field of network practice has not kept up with this dramatic increase in networks.

The field of network practice has not kept up with this dramatic increase in networks.

All too many networks are floundering, struggling with knowing how best to support network leadership, how to structure their network, and how to organize action. Too many try to adapt an organizational frame and find that network growth and innovation are inhibited.

An organization is an organization is an organization. There are ample books, associations, training programs and consultants available, so that setting up a new nonprofit is fairly straightforward.

But networks come in many shapes and sizes, and recipe books aren’t as useful for this type of entity. There are only a handful of network consultants in the entire country, only a few books on network formation, and little research has been done on the most effective structures and operations for networks. Add to this the fact that only a few foundations are supporting networks, and even fewer are supporting the development of the field.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="25px"]Let’s support networks together!

Over the course of the coming year, I hope to gather a group of individuals and foundations who understand the extraordinary potential of networks and care passionately about developing the support and knowledge that is needed so that all networks can be transformational and system shifting.

I plan to write blog posts at least weekly about every aspect of network practice I work on and send these posts out via an enewsletter. I hope I can convince some of you to contribute to this blog as well. Just respond to this post and I will explain how this can be done.

I also will be developing and offering a wide range of free materials and low-cost modules (will usually include a video, powerpoint, and activity sheets) during the coming months.

I am hoping that you will help think through the development of a platform that encourages networks everywhere to share what they have learned and where people interested in learning collaboratively can find each other.

Let us know what challenges you have faced in forming and operating a network and what would help you with those challenges.

I invite you to respond to this post with your thoughts, comments and expressions of interest in this project. Let us know what challenges you have faced in forming and operating a network and what would help you with those challenges. What would you like to learn? Explore with others?

We can only make progress on this together!

June Holley

Free Worksheets

We are now offering two network worksheets at no cost.

The first is the Network Weaver Checklist, revised from the NW Handbook version and in an easy to print pdf format. [ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]This checklist is great to give to people in your network at a face-to-face gathering. Have them spend 5 or so minutes to take the survey. Then have a chart paper (or 2-3 if the group is large). Using a marker, make a line down the center of the the paper and then one horizontally across from side to side. Mark the upper left quadrant with Connector, the upper right quadrant with Facilitator, the lower left quadrant with Project Coordinator, and the final quadrant with Guardian. Then have people put a red dot in the quadrant where they got the most 4s and 5s, and a green dot in the quadrant they would like to learn more about or do more.

Have them pair up with another person and talk about what they learned about themselves as a network weaver and what they would like to learn.

Then have the whole group notice the quadrant(s) where it is strong, and the quadrant(s) where there aren’t many people currently working. Notice which quadrant has lots of green dots - the network may want to do some explicit organizing of training in this are.

To download the Network Weaver Checklist: CLICK HERE

The other free worksheet, Questions for Deep Reflection, is a set of 20 questions that you can use for reflection in your network project follow-up. This list of questions is designed to help you observe what worked and where you might improve.[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]To download Question for Deep Reflection: CLICK HERE.

We will be adding new free items each week and will let you know when they are available through our e-newsletter. To sign up for the e-newsletter click on the button below.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

A NETWORK OF NETWORKS

Editor’s note: I’ve become more and more convinced that networks are much more effective when they are also part of networks with other networks, where they can share information, learn, support each other with challenges and organize larger collaborative actions especially policy change. We will have a series of blog posts in the coming weeks about the different types of networks of networks and steps in developing them.

Food system networks have been in the forefront of this development. Here Ken Morse describes the Maine Network of Community Food Councils.[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Higher Level Network of Networks

I co-coordinate the Maine Network of Community Food Councils (MNCFC), made up of a growing number of community councils (currently 12, mostly multi-town) that act as local networks, with the Maine Network knitting these together in a Network of Networks.

For the last year, we have been organizing conversations with many other Maine groups with the idea of weaving together the over 100 groups, networks and non-profits working towards rebuilding Maine’s food supply. So a higher level Network of Networks, or you could almost say a Network of Networks of Networks.

We try to study biological models of organizations, seeing “networks” as a biological approach to social organization, much the way sustainable food systems are a biological alternative to industrial agriculture.

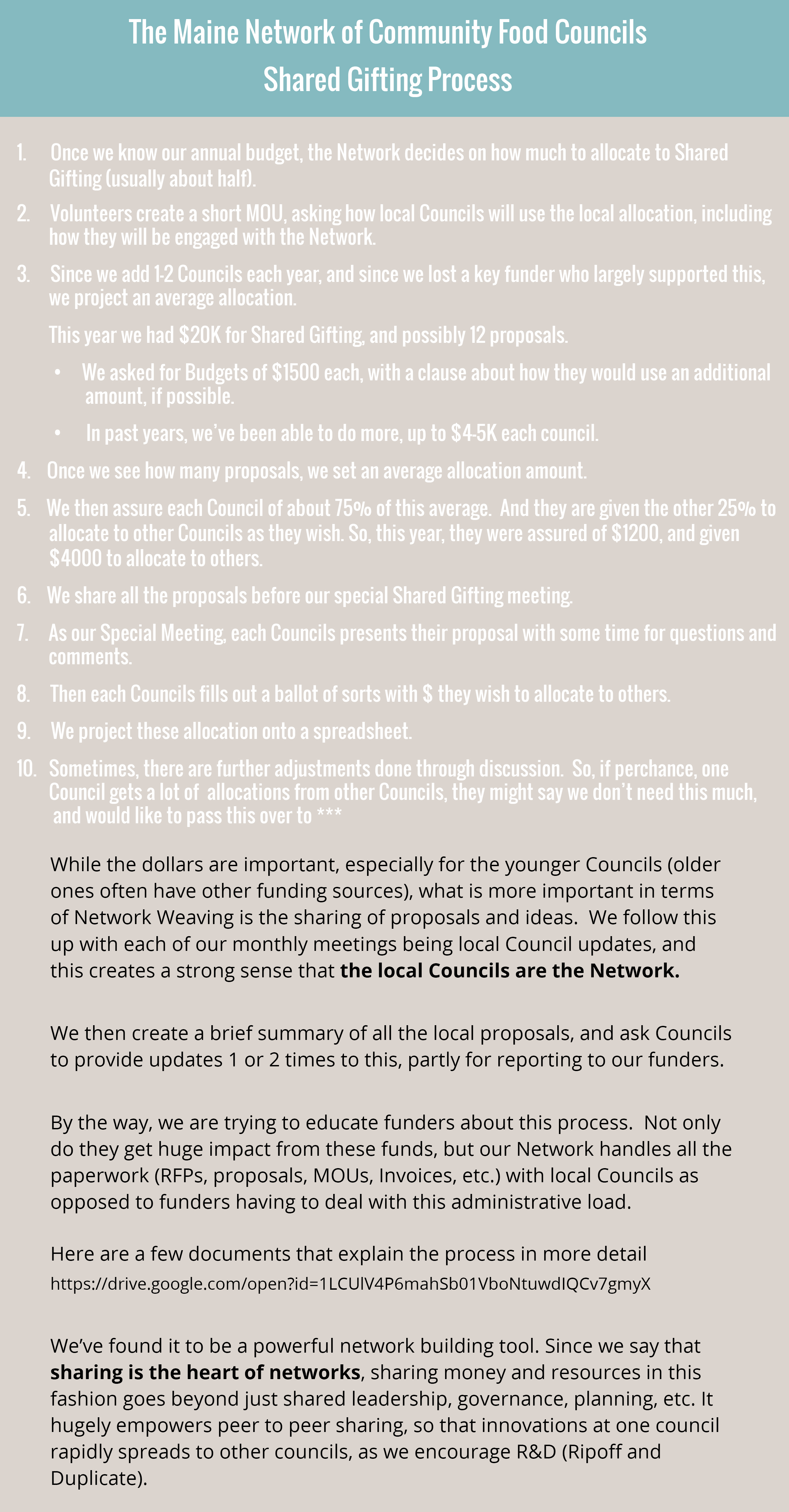

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]The Shared Gifting Process

One tool we have used within MNCFC is our Shared Gifting process. MNCFC is largely grant supported and we devote about half our budget to allocations to local councils, using a Shared Gifting process that we adapted from RSF Finance in California. All Councils submit proposals for this funding, all proposals go out to all Councils, then we have a special Shared Gifting meeting, where each council presents their proposals. Each Council is assured of funding for part of their work, and then have an allocation that they can share with other Councils. [ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]Here are a few documents that explain the process in more detail.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]Enriching Peer to Peer Sharing

This process mightily enriches the peer to peer sharing at the heart of MNCFC. Each Council learns about the work of the others, and then our meetings throughout the year are heavily focused on Community updates. Councils really begin to feel like they are the network, and innovation is greatly accelerated through replication of local initiatives across the Network.

We are interested in other network building tools like this. And in our “networks of networks” work, we are especially interested in questions of structure and communication ecosystems. And stories about how we can help folks who are somewhat stuck in organization or institutional frameworks to make the leap into network mindsets.

So, in any regard, we are delighted to be connecting with you and other national partners to dig deeper into this cutting edge work. [ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]

Ken Morse

Community Food Strategies

Co-Coordinator, Maine Network of Community Food Councils

Leadership Team, Maine Farm to Institution[ap_spacing spacing_height="15px"]

Another wonderful resource Ken shared with me is a video call with four State Food Networks of Networks https://youtu.be/6wgIvqzHs8E. If would like to learn more about statewide food networks, also check out this article by University of Minnesota Extension on Cultivating Collective Action: The Ecology of a Statewide Food Network (2015)

Starting a Self-Organizing Learning Group to Write a Book

It's bothered me for a long time that very few folks in the non-profit sector produce practical materials that others can easily adopt or adapt. I'm a prime example of that. I've been trying to write a book about self-organizing for two years, and haven't made much progress because I’ve been too busy doing the work. But recently I had an interesting thought. Why not model a process for writing a book that embodies the principles of self-organizing, and forces me to integrate reading, thinking and writing about self-organizing into my already crammed schedule?

So first I found someone to help keep the process going --- Susan Rossetti. Besides being a great writer, she’s smart, interested in the subject, and someone who would make a great partner in this emergent process. Together we decided to act on a suggestion from Gigi Barsoum that we start a learning cluster on self-organizing. Not only would the learning-cluster keep us accountable, but as Steven Johnson suggests in his book and TedTalk, “Where Good Ideas Come From,” the collective wisdom and thinking of the learning cluster would be much more likely to yield new, truly innovative ideas about self-organizing than anything I could generate myself.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]How does our learning cluster work?

First, we set up a Google Docs folder that includes the group’s contact list and two working documents: an annotated bibliography, and a document for the group to capture its research and musings on the definition and fundamental characteristics of self-organizing. Susan and I “pre-seeded” both documents, and in the annotated bibliography we included additional columns so the group can track who is reading what, add topic tags and hot links to original sources, and rate the relevance and quality of each reference.

Next we used Doodle to schedule our first video conference, and sent out a short survey using Google Forms to the group to find out what their interests are in participating.

Last week we held our first video conference using Adobe Connect. During the session, we outlined how the learning cluster will work, how we will communicate with each other and share back the learnings from the cluster (what we call our “communications ecosystem”), and we presented our working definition of self-organizing.

In future sessions, members of the group will take turns presenting their findings from their research, and together, we’ll develop an accessible conceptual framework for self-organizing, and identify and test tools and practices that we will share with the field. Be sure to stay tuned as we begin this journey of discovery together!

What has been your experience with learning groups? What can we learn from your experience? Do you know of anyone else trying to write a book this way?

RE-AMP's Pool of Funds

One of the issues for networks is how to determine priorities and have sufficient funding to support a set of innovative, experimental projects. RE-AMP, a climate change network of around 125 organizations and foundations in the Upper Midwest, has had tremendous success with a pooled fund with funding from a group of funders combined into one fund with joint decision-making. In my interview with Rick Reed from the Garfield Foundation (which has been the catalyst for this network), he explains how the pooled fund works.

When RE-AMP was first formed, Garfield Foundation made a conscious decision not to set up a pooled fund right away. They felt that building trust and giving funders experience collaborating needed to the first on the agenda.

However, they did ask other foundations to support the infrastructure of the network by contributing $50,000 to cover the costs of a well-run network: a network facilitator, gatherings, mileage and so forth. The argument was that if the network worked well their investments in member non-profits would result in greater impact.

They recruited the Rockefeller Family Fund, which is a 501c3 endowed fund, to be the fiduciary agent. Any 501c3 can play this role if it has the internal capacity to receive invoices and write checks and is willing to do so, often for a small percentage of the total amount deposited. After a number of years RE-AMP began to use the Michigan Environmental Council for infrastructure expenses because they were willing to write many small checks needed for travel and gatherings.

The infrastructure budget (which now includes stipends for working group coordinators and other staff, communications, and the annual meeting) went from $350,000 the first year to its current $900,000.

During the first 3 years (before the pooled fund), RE-AMP working groups came up with priorities. Funders who were part of the network then took these seriously and used the priorities to determine the focus for their funds. In addition, the foundation working group looked at these priorities and was able to use them to recruit new foundations to the network. As a result, funds from any single foundation were increasingly leveraged. This early strategy still allowed funders to have considerable control over their funds. During these three years, funders attended annual meetings and working groups where they were able to build relationships of trust with other network members and could see how the network and the working groups operated. This increased their confidence in the network, and helped them move to the next stage.

After three years, Garfield saw that that money needed to move faster and be more focused so they decided to start a pooled fund. The idea was for a set of funders to put money into a single fund, where decisions for all the money would be made by a funding group composed of funders and working group coordinators. A pooled funding approach could support a more bottom up, state-based prioritization process that was more in touch with real opportunities and needs.

Initially, only Garfield put in funds. But six months later a second foundation matched Garfield’s funds, and then shortly after 2 more foundations each put in a million dollars. After that growth of the fund was rapid.

So it takes one foundation willing to lead and take the first step, then asking others to join them.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"] 1. The prioritization and decision-making process

In state based meetings, the member organizations identify opportunities for impact: this is what we can do in our state given current politics, public sentiment, etc. These priorities generally fall under the rubric of one of the working groups (which are quite broad areas of focus).

So one state might send in 5 ideas, of them 2 go into one working group, 3 in another. If the topic combines two areas, then it goes to both working groups. The funding group (composed of all funders who contribute dollars and the working group coordinators) meets to make strategic decisions. They may know that action in one state could leverage change in all the states, so put resources there rather than spread it around. They piece together a portfolio that is really going to make a difference for the whole region.

Then collaborations of organizations go back and write proposals. Each working groups leader picks a partner from the set of foundations to help them review the set of proposals received, and then make a recommendation to whole funding committee. Working Group leaders tend to have a broad sense of what is happening in the region so the discussions have considerable collective intelligence! Much better decisions are made because recommendations are given a reality check by the other working group coordinators.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"] 2. The reporting and accountability system

The most important aspect of reporting for RE-AMP and its funders is that what is reported helps everyone learn and adapt. Reporting is not so much for checking to see if grantees did what they said. Everyone agrees RE-AMP wants impacts; but they put an equal emphasis and seek to reward learning.

RE-AMP has an online system for reporting (password protected for members only). It also has a knowledge manager (originally called a learning and progress manager) who helps come up with the questions in the reports so that they really capture learning that will be valuable to others. Reporting of mistakes is encouraged so that everyone can learn from that.

Financial reporting is only shared with the foundations. Much of the way accountability works in RE-AMP is through peer accountability. People on the funding committee know a lot about all the organizations involved and how they are doing. This might be harder in a national network.

If grants are not working out, Garfield will often have a talk with the organization. Also, if a grant is given and the organization gets very fast results, the money is not returned but repurposed. They don’t penalize success.

Reporting is organized by working group or leverage points. Grantees are asked to report every six months on their most important accomplishments.

Reporting shows allocation of funds, and interpretation of why allocations were focused the way they were. For example, initially 2/3 of the money was going into stopping new coal plants from construction. Then in 2009 most plants were shut down, so shifted to retiring existing coal plants and increasing policy to support alternative energy.

Rockefeller still does the fiduciary for the large grants. Garfield makes a grant agreement with Rockefeller, then Rockefeller subcontract. Garfield does all the due diligence to make sure money being spent appropriately so Rockefeller only does the financial reporting. (Takes high level of trust) Still trying to figure out how to give organizations general operating support which can make them more flexible.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON RE-AMP see Transformer by the Monitor Institute

Best Practices for Communities of Practice/ Learning Networks

How do you develop a dynamic learning cluster or community of practice, with engaged members who are generous in sharing their knowledge and experience?

These practices comes from my experience creating several communities of practices and a world-class professional network for leadership and organizational development consultants, the Boston Facilitators Roundtable.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]1. Identify Community Guidelines

Set guidelines to support connection based on mutual learning and support, that encourage sharing of information and that discourage people from marketing to each other. Mutual learning also means coming together to learn with and from one another, without a need to have all the answers.

Additional guidelines: interactive meetings with some presentation and a lot of conversation, in small and large groups, and community building.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]2. Format and size of the cluster

- If relevant, the conveners should determine the ideal number of participants; there is often a benefit to keeping the group small if people are going to disclose their learning edge or challenges in their work.

- For some organizations, diversity of participants is desired, so the conveners should determine the characteristics of participants (diversity of organizations, regions, race, ethnicity, etc.)

- Decide if this will be an open or closed group; this relates to the size, as stated. If it’s an open group, have participants identify ways to integrate newcomers into the group.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]3. The first meeting

- Identify the shared learning objectives

- Start the cluster with each individual identifying his/her learning objectives, and then identify those objectives that are shared by most people.

- Identify topics for discussion (you might choose one of these for the first meeting)

- Spend the bulk of the first meeting on content, not on logistics or on technology. People are eager to hear “what’s this group about” and “how do I connect to this topic and to this group?” Attend to logistics and technology towards the end of the meeting.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]4. Format of meetings

The convener should solicit topics of interest from the group, either at the end of each meeting or prior to the next meeting. Once the agenda is set, send a reminder 1-2 days before the meeting with logistical information – date, time, website, conference call number. People often misplace these messages if you send them earlier than that ;) For the first 1-2 meetings, invite people to join the session 10 minutes early to check their connections, their audio and video, access to the website, as necessary. That way you can start the meeting on time.

For the meeting itself:

- It’s nice to start with a check-in – what’s something exciting that happened to you in the last week/month; what are you looking forward to next month; or, what are you hoping to get out of today's meeting? [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Announce the agenda with time estimates. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Facilitate the content. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Conduct a brief evaluation. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Plan for the next meeting: what's the topic, who's going to present a case or lead the discussion, what materials will be sent in advance, what's the date and time.

The evaluation give you a feel for the value that participants are getting out of the group, and to make improvements or adjustments that will enrich their experience. It can be a Plus/Delta – what worked well and what can we improve; it can be a “Continue/ Stop/ Start” – what should we continue, stop and start doing.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]5. Participants own the group

This comes from the self-organizing principle of adult learning – adults know what they want/need to learn and they can take responsibility for their learning. The degree to which participants organize the topics may depend on the nature of the group. In many cases, it's up to the participants to identify topics for conversation, and rotate the roles of presenting a topic, choosing a book to read and discuss, generating cases for discussion. Peer-assists can also be very valuable. A participant who has questions about a project s/he is working on can present it to the group to get their suggestions.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]6. Foster Communication between participants

Participants want to be able to communicate with each other between meetings. Build a platform for multi-directional communication for the purpose of networking, potential collaboration and for people to learn who they can call on with future questions. This builds the density of connections and strengthens the group for the long run.

[ap_spacing spacing_height="20px"]7. Technology

There are many platforms to use for virtual meetings with audio, and some with video components. Some platforms are free; you have to pay for advanced features. Some things to consider:

- Do people need/want to see one another? Look at Adobe Connect, Zoom, Google Hangout. Check the capacity for the maximum number of webcams. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Will you want to have breakout sessions? Look at StartMeeting, AnyMeeting, Maestro Conferencing. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Do you need to share your screen? Adobe Connect, StartMeeting, Google Hangout. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Share documents? GoogleDocs, GoogleDrive.

With any of these platforms you’ll want to check on the features, the ease of use, and the support. And always test them before the live session, because Murphy’s Law sometimes catches you off-guard: If something can go wrong, it will ;)

Questions? Contact me: abby@skillfulfacilitation.com

GOOD LUCK!

Abby