“Entangled” Social Change: From Inter-action to “Intra-Action”

“What is at stake with quantum theory is the very nature of reality. Should reality be understood as something completely impervious to our interventions, or should it be viewed as something responsive to the very existence of human beings?”

Christopher Fuchs (physicist)

A mark of a good book for me is one that challenges my thinking, moves my heart, and also resonates in my body. That has been the case while reading Karen O’Brien’s You Matter More Than You Think: Quantum Social Science for a Thriving World. I want to give a big “thank you” and shout out to Fabian Pfortmüller who made this recommendation to me during a rich conversation a few weeks ago.

O’Brien’s book makes the case for bringing a quantum physics lens to the social sciences and to thinking about social change, even as she acknowledges the doubters and detractors who see this as an inappropriate move. Indeed, in posting about the book on LinkedIn recently, I was a little surprised to see a couple of comments attacking the idea of importing quantum considerations into the human realm. In anticipation of this, O’Brien notes that while quantum and classical physics, as well as the “hard” and social sciences, may have different applications, they are not totally separate from each other. Furthermore she writes:

“… given the nature of global crises, maybe this actually is an appropriate time to consider how meanings, metaphors and methods informed by quantum physics can inspire social change, and in particular our responses to climate change.”

So I have been doing what she invites – playing with these different ideas and concepts from the quantum realm and seeing what they stimulate. One I want to lift up here is the notion of subjectivity versus objectivity, and specifically that we are always participants in the world, never simply “detached observers.” This is not simply meant in an emotional sense, but that our very act of observing is actually an embodied intervention and can change what we see and also how we see the world. This “entanglement” (meant more metaphorically here, rather than in the formal scientific sense) asks us to consider how we are already connected, or part of a larger whole.

O’Brien spends some time exploring beliefs as being central to both what is possible and what is actually realized in our lives and world. If we believe we are completely separate from one another, for example. what do we and don’t we consider possible or worth while? If we believe we are more tied or woven, then what might we be inclined to do? The work of Karen Barad is referenced in this respect, pointing out the difference between talking/thinking about “inter-actions” of separate entities versus “intra-actions” among entangled elements within a larger whole. This is not just about a difference in language, but a difference in perceived and acted upon futures.

What comes to mind is a mantra of sorts that Valarie Kaur puts forward in her justice work focused on addressing the dynamics of othering and oppression, as well as in her book See No Stranger: A Memoir and Manifesto of Revolutionary Love –

“You are a part of me I do not yet know.”

Similar to this spirit, john a. powell offers the following in Racing to Justice: Transforming Our Conceptions of Self and Other to Build an Inclusive Society:

“There is a need for an alternative vision, a beloved community where being connected to the other is seen as the foundation of a healthy self, not its destruction, and where the racial other is seen not as the infinite other, but rather as the other that is always and already a part of us.”

I am also reminded of the peace-building work of John Paul Lederach, and this from his book The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace:

“Time and again, where in small or larger ways the shackles of violence are broken, we find a singular tap root that gives life to the moral imagination: the capacity of individuals and communities to imagine themselves in a web of relationship even with their enemies.”

If we treat the so-called “other” (whether human, other animals, plants … ) as apart from us, or as in some sense fundamentally threatening (“the enemy”), then where does that lead? The point here is that reality is not just “reality out there,” it is also what we make of it. We have a say. We matter. What we believe matters. What we do matters. Embracing “a bigger WE” matters. We can “bring forth worlds,” (to quote Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela’s Santiago Theory of Cognition) at least to a certain extent. And whether this is about imagining or re-membering, acting “as if” we are joined in something larger can seemingly create tangible results, while also acknowledging that dynamics of power and privilege are important to consider in terms of who may be inclined to make first gestures and how these will be received.

“Between me and not-me there is surely a line, a clear distinction, or so it seems. But, now that I look, where is that line?

This fresh apple, still cold and crisp from the morning dew, is not-me only until I eat it. When I eat, I eat the soil that nourished the apple. When I drink, the waters of the earth become me. With every breath I take in I draw in not-me and make it me. With every breath out I exhale me into not-me.

If the air and the waters and the soils are poisoned, I am poisoned. Only if I believe the fiction of the lines more than the truth of the lineless planet, will I poison the earth, which is myself.”

– Donella Meadows, from “Lines in the Mind, Not in the World”

* * * * *

A few years ago I was diagnosed with a benign tumor on my left acoustic and balance nerve (an acoustic neuroma). As the tumor continued to grow, albeit slowly, I made the decision to have radiation treatment two years ago (six months into our new COVID reality). What was presented as a fairly straight-forward outpatient procedure turned into quite an ordeal as I had a strong reaction to the treatment. What followed was dizziness, terrible tinnitus, poor sleep, muscular pain, headaches and occasional “nerve storms” in other parts of my body. After a few months of extreme discomfort I went to see a very adept acupressurist and holistic healer who made the observation that I seemed to be trying to separate myself from that part of my body, tensing against it, rejecting it, and the result was further exacerbation. With her help, over several months, I gradually got reacquainted with that sensitive area (really getting to know it for the first time), and through slow and steady integrative body work, began to relax and reclaim that part of me in a way that has brought greater ease to my overall system and life.

The very energizing thing about that work with this healer is that it has helped not simply to address discomfort in one area of my body, it has positively impacted other parts that I did not even realize were misaligned and/or listless until this crisis occurred. I take it as ontological truth that I am all of my body (though not simply my body), yet for many years (and especially recently) I had not been acting like that (consciously and unconsciously), with real health-related ramifications. Extend this metaphor (separate –> connected, inter-action –> intra-action) to other “bodies” of different sizes. scales and dimensions, and where might that lead?

What excites me here is acknowledging the entanglements that we do not yet know, or cannot possibly hold in our minds alone given the immensity of the world. This is where “thinking and acting in a networked way,” with some faith and conviction, comes into play for me, along with an orientation towards equity. In particular, I think of the encouragement offered in these words from the late long-time community organizer and political educator Grace Lee Boggs:

“We never know how our small activities will affect others through the invisible fabric of our connectedness. In this exquisitely connected world, it’s never a question of ‘critical mass.’ It’s always about critical connections.”

What critical connections and small moves might we make in this intricate, [vast/intimate] and mysterious world that could yield big and needed changes in our communities and lives?

About the Author:

Much of Curtis Ogden's work with IISC entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food public health, education, and economic development systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

featured image by Kevin Dooley, shared under provisions of Creative Commons Attribution license 2.0.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

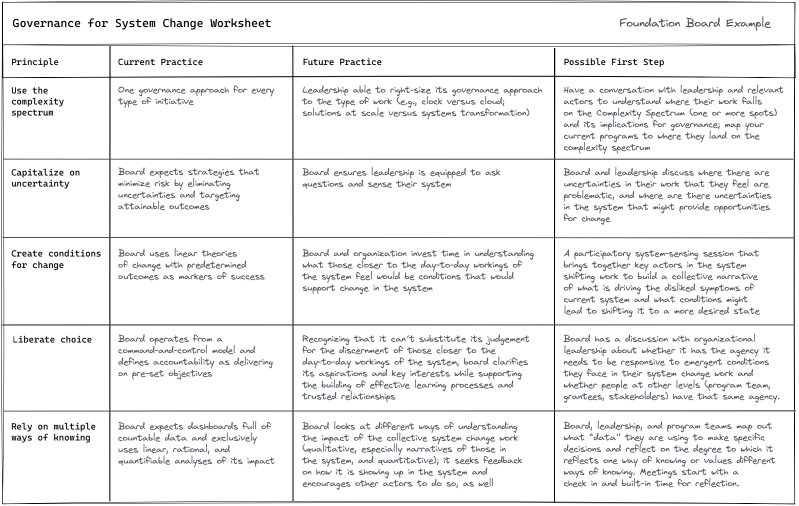

Governance for System Change

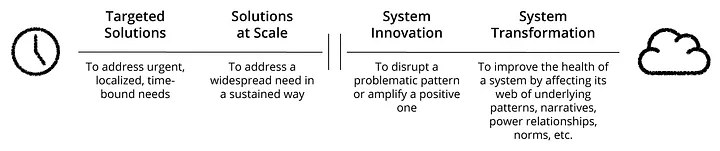

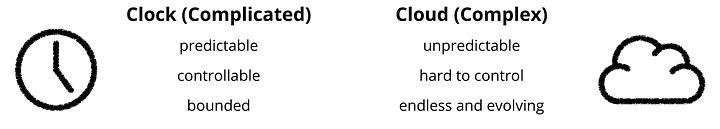

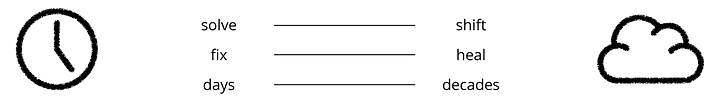

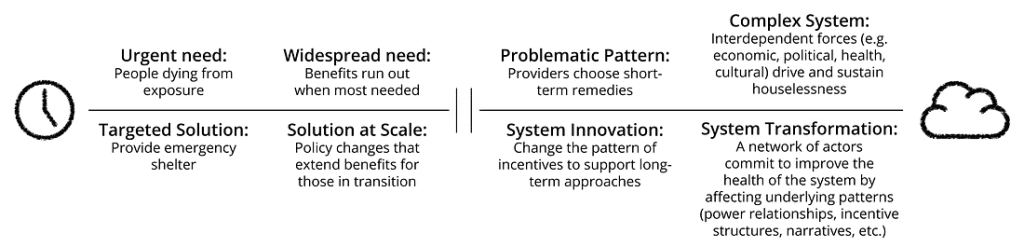

The Complexity Spectrum blog describes how clock and cloud (non-system change and system change) approaches require fundamentally different strategies and tactics. The same goes for the mental models and processes we use to govern system change work.

In fact, governance for system change may not look much like traditional governance at all. Webster’s defines governance as “overseeing the control or direction of something.” Because system change work is emergent, long term and comprised of dispersed and diverse actors, centralized control and oversight is unworkable if not impossible.

Rather, system change work requires distributed decision making in pursuit of a common aspiration and in response to emergent facts on the ground. While centralized control may be impossible, there are ways to bring coherence to this work, increasing the probability of shifting a system to a more desired state.

In this case, governance applies to anyone who makes important decisions that affect the probability of success of a collective system change endeavor, and not just to members of a board of directors.[1] This type of governance is difficult and often requires building a range of new practices over time. Here are a few practices that may help:

- Capitalize on uncertainty to lower risk and increase chances for success.

- Focus on creating the conditions for change over short-term outcomes.

- Liberate choice rather than trying to control it.

- Rely on multiple ways of knowing as you navigate the journey.

Practice #1: Capitalize on Uncertainty

“Uncertainty is an uncomfortable position. But certainty is an absurd one.” -Voltaire

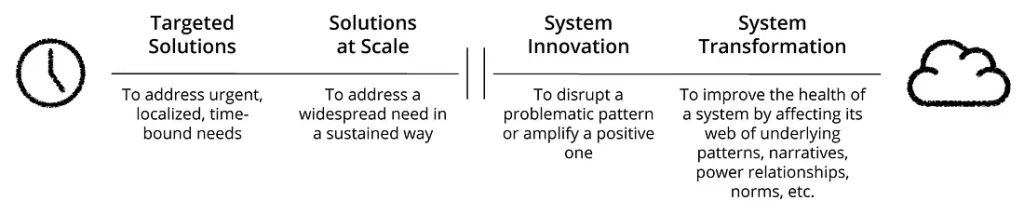

Depending on where you engage on the Complexity Spectrum, uncertainty can be a problem or it can provide a valuable opportunity.

Targeted solutions require a technical approach where you move efficiently along a mostly known pathway from a known problem to a known solution. Take for example a population that has been displaced by a natural disaster. We have experience dealing with this type of situation (known problem) and delivering the targeted solution of emergency shelter (known solution) though various tried and true means (mostly known pathway). In this case, uncertainty can be disruptive because it creates barriers between the problem and the solution.

Solutions at scale usually require an adaptive approach (think Human-Centered Design).

For example, in California many more people were eligible for benefits to alleviate poverty and food insecurity than were applying for them. The reasons why the problem existed were fairly well understood (sufficiently defined problem). In response, Code for America talked to people to understand why they weren’t applying and how they could provide a solution. They built an app, iterated it, and eventually launched a product (GetCalFresh) that greatly increased the number of eligible people applying for benefits (iterated to find a solution that was initially unknown).

An adaptive approach requires a fair level of certainty about the definition of the problem and its causes — enough to support a process of managed uncertainty in which you experiment to find deeper causes and solutions to the problem.

System transformation calls for an emergent approach.[2] In an emergent approach, while you are likely certain about the negative symptoms of the challenge (e.g., high levels of poverty or inequality), the deeper drivers of the problem and reasons for its persistence are mostly unknown or misunderstood. Consequently, the ways to address these drivers are also mostly unknown (or unformed). The key is to nurture the conditions that will support the system healing itself (e.g., understanding the systemic drivers of the challenge and supporting the emergence of ways to address them).

In an emergent approach, uncertainty unlocks opportunity. When complex challenges persist over time despite efforts to address them, there is often a sense of frustration, even despair. However, this can lead to the realization that we don’t have all the answers, which can make us more open to thinking differently.

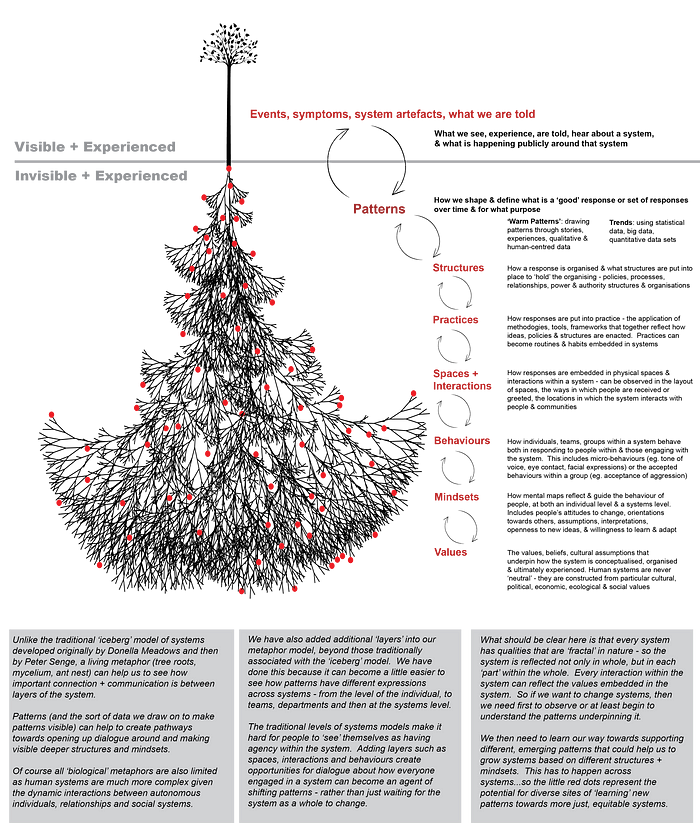

Some forms of systemic analysis, like dynamic system mapping or participatory futures, provide a structured process for thinking in new ways about an all-too-familiar problem. When doing participatory system mapping, aha moments often arise when participants identify a pattern that explains why change has been elusive. It is empowering to see an old problem from a different perspective and find a possible path forward.

Effective system sensing should lead to confidence that you have “good uncertainty” — or trust that there are good questions to explore and a way to experiment and learn more about the system and how to engage it. Think of uncertainty as a gateway to doing things differently and finding ways to unstick a stuck system.

Practice #2: Focus on Creating the Conditions for Change

Uncertainty is uncomfortable because it increases our fear of failure. It makes us anxious. One common but ultimately unhelpful response is to over-rely on short-term substantive outcomes that are a small piece of the ultimate outcome we want to see. [3] For example, if we are looking to end human slavery in global supply chains, we might measure progress by looking for annual percentage reductions in the estimates of slave labor by 5% or so each year.

It is wise to understand the impacts our work is having in the short term, if for no other reason than to detect and mitigate potential negative impacts. However, there is a danger of using pre-defined, substantive outcomes as waypoints to navigate our way on the journey toward long-term system change.

Specifically, there are two key dangers:

- Short-term outcomes dominate our time, attention, and resources and reduce commitment to long-term change. According to neuroscientist Ian Robertson, “success and failure shapes us more powerfully than genetics and drugs.” This means short-term successes can lead people to invest more time, resources, and emotional commitment in concrete short-term outcomes instead of longer-term, hazier systemic shifts. Moreover, grantees often need to trade annual impacts for continued funding, so pre-identified short-term outcomes take priority.

- Short-term impacts can be bad predictors of long-term, systemic impact. In complex systems, impact is not static. What may seem like a good outcome in the near term, might drive negative downstream impacts in the months and years ahead. Basing future investments mostly on short-term outcomes can lead to bad long-term investments.

The implication is an inexorable pull away from making the hard choices and risk tolerance needed for system change. As a result, the pursuit of specific substantive outcomes in the short term may make it more likely a system change effort fails in the long term.

Fortunately there is an alternative. Alice Evans, who in her time at Lankelly Chase helped build their systems practice, said a key enabler of their work was the realization that creating the conditions for system change should be their focus rather than targeting specific outcomes those conditions might produce.

For example, there are a few generic conditions that will apply, in some form, to most system change initiatives. These include the degree to which important system actors can:

- See their context as a complex system and use that shared understanding to inform action and increase the potential coherence of distributed action.

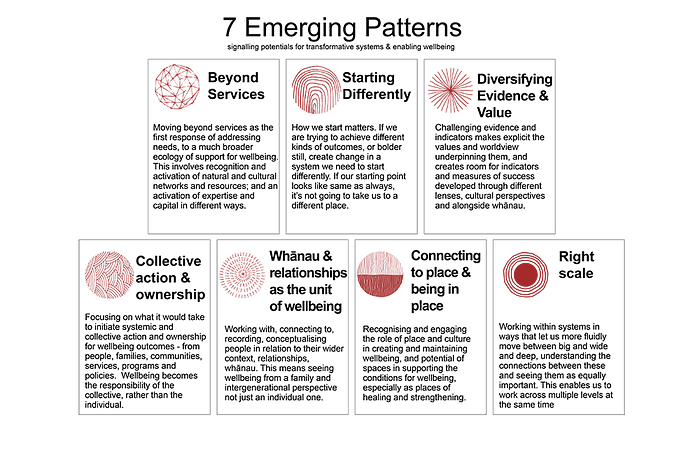

- Identify and engage patterns that people believe will unlock change (e.g., weakening patterns that sustain the problem or strengthen bright spots that can shift the system).

- Build or strengthen connections, networks, and information flows across the system.

- Build an infrastructure for learning and, as Marilyn Darling says, “return that learning to the system.”

Elaborating these and other conditions that might support system change requires a participatory process that prioritizes the voices of those closest to the day-to-day operations of the system.

As we look at the conditions we are trying to cultivate, we must also look at those in ourselves and in our organizations. We are all part of the respective systems we are engaging and it’s critical to contend with power and who is making decisions both within an organization and in a broader system impacted by those decisions. If you haven’t already done work on your own relationship to power and how it impacts your work, now might be a great time to dig in. Consider asking:

- How are we showing up in the system? What feedback are we getting about how we’re showing up? Are we working in a system-informed way? How do others experience our presence?

- What is the quality of our relationships with other key system actors? How have we prioritized the voices of those closest to the context?

- How do we understand our own power in the context we are working in and the people we are working with? How do others perceive it? How can we engage others in an honest conversation about our relative power?

Fortunately, changing how we show up in a system shifting initiative is a condition over which we have the greatest control. Unfortunately, many of us, especially funders, show up in ways that replicate or entrench unhelpful power dynamics that constrain choice and make distributed decision making impossible. This means a critical early condition for system change is understanding and adapting the ways in which our organizations — and even ourselves — work. For more thoughts on internal organizational conditions and how to work toward them, see Building Emergent Organizations.

Practice #3: Liberate Choice

Successful system change requires those closest to the day-to-day operations of the system to be highly adaptive over time in response to emerging realities.[4] However, this is hard to do with traditional governance processes that seek to maximize control and minimize risk.

For example, a standard grant agreement trades funds for outcomes identified by the donor, which replicates the power dynamic of “those with resources call the tune.” This dynamic too often prioritizes donor interests rather than those most impacted by the funding, removes agency from those closest to the context, and creates highly transactional relationships.

If funders behave in ways that reduce the agency of these actors, they inhibit their ability to work for system change.

The alternative to donors limiting choice is to use what Cyndi Suarez calls “liberatory power,” or the ability to “create what we want” by transforming “what one currently perceives as a limitation.”[5] A key question for donors wishing to support system change is, how can we increase the ability of key actors in the system to effectively connect with each other, sense, sense-make, act on, and learn from their system?

Each level of actor in a system change initiative can liberate the choices of actors in the system. Liberating choice is not the same as giving more choices — it requires both the presence of choice and the agency to act on it. A board of directors needs to liberate choice for organizations they oversee; leadership of an organization needs to liberate choice of its program teams; program teams need to liberate choice of grantees and partners; grantees and partners need to liberate choice of stakeholders and community actors; and based on how information flows in the system, stakeholders can liberate choice for program teams, etc.

This is not the same as simply giving money and getting out of the way. Liberating choice does not mean removing all structure. Many argue there is no such thing as structurelessness when it comes to any kind of group activity, especially when one actor is providing significant resources to support the work of other actors.[6] Donors need to provide enough structure to enable choice, but not so much as to prematurely curtail choice.

The key is to create minimally sufficient, helpful structure. For donors supporting system change, there are some key components to creating minimal structure, which include:

- Articulate a common aspiration or guiding star.[7]

- Clarify boundaries by articulating key interests and values.

- Establish an infrastructure for learning.

- Invest time in building trusting relationships among system actors.

Of these four points, clarifying boundaries or guardrails may be the most difficult. An unhelpful but familiar way of doing so is to provide directives to either do or not do something. A more useful approach is the “even-over statement” as developed by Tom Thomison and popularized by Aaron Dignan.

The benefit of even-over statements is that they share how different actors in the system might make tradeoffs between key interests and values. The statement consists of two “good things” and says, “if confronted with a choice, I would choose this good thing over that good thing.” However, it aims to preserve the agency of an actor to make a decision in light of the specific situations that they find themselves in.

Some generic even-over statements that liberate choice for system change include:

- Prioritize responsible, smaller experiments even over concentrating resources on large-scale bets.

- Invest time in building trusting relationships even over delivering on preset timelines.

- Value responsible learning even over clear-cut wins.

- Foster regular, honest feedback across the network of actors even over preserving harmonious relations.

Whatever boundaries you try to set, and however you set them, they will be wrong in some respect. This is where a dynamic learning process is essential. Part of that learning process needs to ask to what degree are the boundaries and common aspiration helpful? In what ways are they affecting people’s thinking and behavior? Are they strengthening agency of system actors or reducing it? What might we do better?

And none of this works if the relationships between actors in a system change initiative are mainly transactional. Because system change work is highly emergent, it requires real time and honest communication and the ability to work in a decentralized way. All of this requires high levels of trust between actors, and this level of trust does not happen unless they invest time in it. This can be particularly difficult for funders who see investing time to build trust as simply increasing overhead.

Practice #4: Rely on Multiple Ways of Knowing

“There is a strong bias in the U.S. dominant culture, one that shows up in the nonprofit sector as well, to value only one way of knowing, the one grounded in data, analysis, logic, and theory — a rationalist’s approach to truth.” -Elissa Sloane Perry and Aja Couchois [8]

Working effectively in complex systems requires strengthening our ability to use multiple ways of knowing. It is essential for implementing the practices described above. Unfortunately, as the quote from Elissa Sloane Perry and Aja Couchois indicates, the default capacity for many in the West is to privilege only one way of knowing — a cognitive, analytic approach.

This is not to say we should devalue rational analysis. Rather, it means putting a high value on the ways others understand their world and make decisions about how to act.

There are various ways to define multiple ways of knowing, from Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences to the model of five minds described by Tyson Yunkaporta.[9] A simple way to look at multiple ways of knowing is: thinking, feeling, and intuiting.[10] At a minimum, it means asking: what do you think about the situation, how does it make you feel, and what is your gut telling you to do? It means listening to how others think, feel, and intuit.

Listening to feelings and intuitions is not the same as following them. Rather, it means understanding how information, situations, and decisions make us and others feel; allowing our intuitions to come to the surface; and not automatically subjugating these to what we might judge as rational or rigorous analysis. It means sitting with differences and uncertainty and valuing the important stories people tell about their system, and not just the numbers they can fit on a spreadsheet.

For many, this is the most disruptive practice for system change governance. It requires us to change how we think about and develop strategy, how we evaluate our effectiveness and that of our grantees, and how we make decisions. It means that good questions are often more useful than seemingly good answers. Fundamentally, it changes how we know what we know (e.g., how we weigh a quantitative analysis versus the lived experiences of partners on the ground).

But as disruptive as it can be, cultivating multiple ways of knowing is worth it. There are several reasons why: from the neuroscience that shows the role of emotions in decision making to the necessity of multiple ways of knowing for advancing equity.

In addition, there are simple, practical arguments for cultivating multiple ways of knowing from a system change perspective:

- If shifting systems involves diverse actors spread across geographies and cultures, different ways of knowing will always exist in the network. This means effective system change work requires the ability to understand and work with those different ways of knowing.

- And, because complex systems are murky and constantly changing, it is naïve to rely on only one way of knowing. Each way of knowing has limits but, together, multiple ways of knowing increase our effectiveness.

- Lastly, multiple ways of knowing are essential because we can’t just reason our way to system change — rather it requires a dynamic connection between head, heart, and gut.

One accessible way to start bringing multiple ways of knowing into your work is to play with meeting structure. Try starting meetings with a check-in question like “how are thinking and feeling coming into the meeting?” Or you could ask something more playful like “what was your favorite movie character as a kid?” A more serious question could be “can you describe a time when you felt truly happy?” Think of it less as an icebreaker and more of a space for people to welcome in their whole selves and deepen relationships. It also helps to build in time for silent reflection in the room, have people journal, or to pair up and process the meeting while taking a walk.

Many people have built more in-depth ways to incorporate multiple ways of knowing. A few I suggest are: the Equitable Evaluation Initiative, for using multiple ways of knowing to build more equitable evaluation processes; Relational Systems Thinking: That’s How Change Is Going to Come, from Our Earth Mother by Melanie Goodchild, for how to realize the benefit of differing world views and ways of knowing; and Theory U by Otto Scharmer, for a comprehensive approach to system change that has multiple ways of knowing at its core.

Next Steps

Learning to use a different frame for how we govern system change is a practice, and it takes time to develop. Devoting time to consciously changing your governance practices is the first challenge you will confront. But remember, systems seldom change on a dime, and neither do we. You might want to start with the system you know best and are closest to — you and your own organization.

One way to start is to use these governance practices as a set of prompts for your own self-reflection and experimentation, such as:

Using the Complexity Spectrum. How are we differentiating among our organization’s approaches along the Complexity Spectrum? Are we developing different mindsets and practices for clock versus cloud initiatives (e.g., solutions at scale versus system innovation or transformation)?

Capitalize on uncertainty. How are we cultivating good uncertainty and capitalizing on it? Are we resisting the urge to create certainty when there is none?

Liberate choice rather than trying to control it. Do those closer to the context feel they are able to make the choices needed to engage the system effectively? How well are our aspirations, guardrails, and learning processes helping us learn from the choices we make? What levels of trust are we able to build?

Focus on creating the conditions for change. What are the conditions that will support change in our organizational system? How well are we supporting them? How might we revise them? How are we understanding what others in the system feel are the conditions that will drive change?

Rely on multiple ways of knowing as you navigate the journey. Are we getting in touch with our own ways of knowing and cultivating openness to others? Are we trying both small and large experiments? (e.g., creating space in meetings for check-ins and reflection time? Building a more equitable evaluation practice or sitting in the tensions between different world views?)

Lastly, give yourself and those around you room and permission to change. Rather than expecting to get it right, focus on getting it better. Together I think we can do just that.

Download a PDF of the blank worksheet

Download a PDF of the example worksheet

Acknowledgement: While I take responsibility for the words used in this blog, the ideas come from dozens of colleagues, hundreds of conversations, and thousands of hours of experimenting and learning by many.

[1] I will often refer to the work of a foundation board because this is the context I know well.

[2] I am using the terms technical, adaptive, or emergent approach instead of technical, adaptive, or emergent strategy to avoid confusion with established writing on these types of strategy. There is a fair amount of commonality of usage of the terms technical, adaptive, and emergent between this piece and earlier works, but there is not 100% overlap and I want to avoid confusion or to imply that I am redefining these types of strategy. For writing on the subject, see the works of Ron Heifetz, Adrienne Marie Brown, and Henry Mintzberg.

[3] In this case, substantive outcomes mean measurable changes to the symptoms of the problem we are concerned with, as opposed to the process by which we work.

[4] This is particularly important when working with complex systems where those closest to the context need the ability to respond to what they are learning. This is what Gen. Stanley McChrystal found in doing counterinsurgency work and wrote about in his book, Team of Teams. McChrystal saw the need to empower choice from units on the ground by creating more distributed decision making.

[5] See The Power Manual by Cyndi Suarez, p. 13.

[6] See The Tyranny of Structurelessness by Jo Freeman who wrote about organizing the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s. Here is a relevant passage: “Contrary to what we would like to believe, there is no such thing as a structureless group. Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power, and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved.”

[7] For guidance on developing a guiding star, see the Systems Practice Workbook.

[8] Multiple Ways of Knowing: Expanding How We Know, April 27, 2017, Non-Profit Quarterly.

[9] Here is a quick description of the five minds.

[10] Here a quick explanation of the science of intuition: “Intuition is a form of knowledge that appears in consciousness without obvious deliberation. It is not magical but rather a faculty in which hunches are generated by the unconscious mind rapidly sifting through past experience and cumulative knowledge.”

Rob Ricigliano is the Systems & Complexity coach at The Omidyar Group, where he supports teams as they engage complex systems to make societal change.

originally publshed at In Too Deep

featured image by kazuend on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

The paradox of transformation: acceptance as a precondition to change

The radical potential of healthy shame... to return us to belonging

This is the paradox: to reach transformation, we must let go of the aspiration for transformation. As psychologist Carl Rogers put it:

The curious paradox is that when I accept myself, just as I am, then I can change.

While I accept this truth intellectually, and it feels doable when it comes to my self-transformation work… I haven’t yet figured out a way to embody it in integrity and authenticity when it comes to my work for social transformation. David Kelleher names the tension I feel:

If you’re going to work with people for change, you have to love them… I’m still stuck with the contradiction of loving someone and making demands on their behavior in the name of justice.

It feels like I’m being asked to let go of my commitment to justice… in order to honor my commitment to justice. I don’t know what to do with that. So today I want to explore a controversial idea: the concept of “healthy shame.”

TL;DR: Toxic shame tells us we don’t belong, and offers no path back to belonging. Healthy shame reminds us that we belong, and warns us when we transgress a social norm that threatens the collective: it invites us to change our behavior, not our core sense of self. We need to cultivate the capacity to heal from toxic shame, and build resilience to tolerate healthy shame… and take action to repair harm and return to belonging. There are four steps: show up with compassion for the other; help them practice self-compassion; co-regulate to feel safe in their bodies; support the practice of new behaviors. To come into right relationship with shame is to exercise power: a tool we can use in service of justice, and to create a world where everyone belongs.

Transform behavior, not people

This feels important to underscore: by virtue of the miracle of our existence, like all beings, humans are perfect exactly as we are. It’s our behavior (at an individual, collective, and systemic level) that needs to change.

When I first started writing this post I paused for a couple days to do another deep-dive into the literature on shame and guilt (building on this post, where I first named the acceptance/transformation paradox, and this one, exploring more collective accountability questions). I want to update/amend my previous conclusions to explore the transformative potential of healthy shame.

To be clear: the way our dominant culture wields shame is incredibly toxic: any shame that contributes to paralysis, that inculcates in its target a fundamental sense of unworthiness harms our goal of enabling transformation. That is NOT what I am talking about here. There is shame that is associated with trauma, and there is shame that is associated with healing and resilience… it is this fraught latter terrain I want to explore today.

Because shame (and guilt) are social emotions that have to do with our sense of (and right to) belong, the core difference that distinguishes healthy shame from toxic shame is whether there exists the possibility of returning to belonging. If the purpose or function of shame is to exclude without offering a path to redemption, it is toxic. If instead the purpose is to illuminate a harm and invite repair… it can serve a healthy function. I appreciate Joseph Burgo’s treatment of the subject, where he explains:

Helpful shame always leaves room for improvement rather than making someone feel fundamentally worthless, with no hope for growth.

This to me is the difference between feeling shamed (you are making me feel something, which may or may not register as fair) and feeling ashamed (I internalize the assessment and agree I have done something I regret; a third party may not need to be present or aware of my transgression in order for me to feel ashamed). Annette Kämmerer explains:

We feel shame when we violate the social norms we believe in.

In this rendering, to feel ashamed is to feel the pain of finding ourselves out of integrity with our own values. As Mark Manson notes:

Our values determine our shames.

Shame defines the conditions of belonging

Shame is a social emotion: it is the enforcement mechanism for belonging. Burgo again:

Human beings developed the ability to feel shame because it helped promote social cohesion.

Social norms define the boundaries of belonging: they are the set of agreements that allow us to function and live in community. In its social expression, shaming alerts community members that they have transgressed a social norm, and invites them to take corrective action, to repair the harm. I love Miki Kashtan’s explanation of how shame functioned in pre-patriarchal societies:

When the behavior of an individual threatens the ongoing cohesion or functioning of the group, and only in those circumstances, that’s when shame emerges as a mechanism for protecting the group from the threat of an individual taking action that might endanger the group.

Burgo agrees:

Our evolutionary ancestors used shaming and shunning to encourage change, to help tribal members reform their transgressive behavior and then reintegrate.

I think of it this way: love is unconditional; belonging is not. Love (for your self as a simultaneously perfect and flawed human) is unconditional; belonging (which includes how you behave in a collective) is conditional on you adopting the pro-social norms and behaviors that allow the collective to thrive. I loved Naava Smolash’s comment on my last post taking up this topic, where she named this tension inherent in the promise of belonging:

The one condition of belonging that makes true belonging possible, is the willingness to excise those who genuinely do not care about others or are unwilling to challenge their own conditioning into dominance.

It is perhaps easiest to understand the value of shame by imagining its absence: to be “shameless” is not a good thing; it’s associated with sociopathy. I’m reminded of that classic line in the McCarthy hearings, which I hear as another way of saying: are you impervious to shame?

Using—and choosing—healthy shame

I believe there is a role for healthy shame to help encourage people to adopt these new norms… but it’s a delicate dance. Take for example the emerging awareness around micro-aggressions: misgendering or deadnaming someone for example, or inadvertently deploying a racist stereotype. I think it’s healthy and necessary to feel that initial sting: it’s to become aware that I have caused harm, and to feel shame. And of course I don’t want to stay in that feeling: it’s deeply uncomfortable. We tend to respond in one of three ways (and let’s assume for the sake of argument that the norm is a positive pro-social norm, as I believe these are):

- Internalize the shame without self-compassion; this transmutes healthy shame into toxic shame: I’m a terrible person, I don’t belong. This not only misses an opportunity for transformation, but it also leaves the harm unrepaired as I retreat into myself and disassociate from the person/people experiencing the impact I caused.

- Reject the new norm and refuse to feel shame: I don’t believe in pronouns, and I refuse to take accountability for my impact. Often this strategy is accompanied by blaming/attacking the person who made visible the transgression: instead of attending to impact, we cast ourselves as victim for not having our intention seen/honored (Jennifer Freyd coined the term DARVO to describe this approach, often used unconsciously). This too misses the opportunity for transformation and for repairing harm. I resonate with Heather Plett’s description of what’s going on here:

People who’ve convinced themselves they are good people… are suddenly sent into spasms when their biases and blindspots are revealed. They can’t fathom the fact that they are capable of causing harm. They haven’t been equipped to hold space for their own shame. Subconsciously, they’re terrified that they will be abandoned and, at worst, banished from the kingdom.

- Accept the new norm, move from feeling shamed to feeling ashamed, and try to do better. To practice self-compassion (now I know, I can do better) and to exercise responsibility for impact (I’m sorry) and accountability to repair (how can I make it better and avoid causing harm in the future?)

Our goal, of course, is to support people in choosing the third path. And: we also want to exercise individual and collective discernment about which norms we want to embrace/internalize, and which we want to rightfully reject.

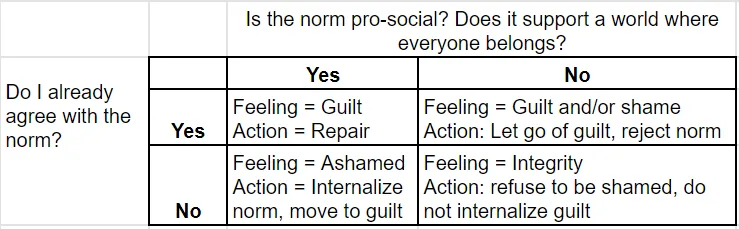

There are many existing social norms that I think are harmful and incompatible with a world where everyone belongs: in those cases, I think it is incumbent upon us to reject the norm and decline to feel the sting of shame. For example, should a man choose to wear a dress, in a world where everyone belongs that’s a perfectly valid and beautiful choice: he should refuse to be shamed for it (and we should refrain from shaming him). Because I’m a nerd, I made up a 2x2 matrix trying to illustrate this.

In this understanding, guilt only occurs when you already accept/agree with a norm: by definition, you can’t feel guilty for something you didn’t know was harmful, because you couldn’t have acted differently. In the case of encountering a new norm, the initial feeling is shame, which you can then transmute into guilt by accepting the norm and committing to repair. Shame researcher Dr. Stephen Finn summarizes his findings:

The goal is to help people tolerate shame and move to guilt… healthy shame is guilt.

Four steps: from shame back to belonging

I love Stephen Finn’s reminder here:

Shame is a social emotion; it can only be healed interpersonally.

If toxic shame tells us we don’t (and will never) belong, then a culture of belonging is one without toxic shame… and one that supports people in processing their healthy shame into guilt and repair and a return to belonging. Matthew Gibson puts it bluntly:

We cannot face our shame alone, certainly not the toxic form of shame that is not ours.

I think there are four steps to supporting transformation, which I want to unpack here.

- Show up with love and compassion: The first step has to do with the motivation and attitude of the supportive partner: if we are sincere about supporting transformation, we must come from a place of love and compassion. Here’s Father Richard Rohr:

What empowers change, what makes you desirous of change is the experience of love. It is that inherent experience of love that becomes the engine of change.

- Practice self-compassion. The purpose of this compassionate witness is to provide a safe environment for them to practice self-compassion. For the vast majority of humans who struggle with self-compassion, the radical act of offering compassion to ourselves is itself the first act of transformation… and those of us who are interested in social change need to support, recognize and celebrate it as such. I credit my wife Jennifer for helping me understand how foundational self-compassion is to the entire enterprise of transformation: it helps us ensure that shame stays healthy and doesn’t turn toxic; it motivates repair instead of paralyzing us into a trauma response. Emily Nagoski is clear on this:

The antidote to shame is self-compassion.

- Feel safe in our bodies: so many of our defenses, particularly around shame, operate at the level of the sub-conscious, and are deeply shamed around trauma. Healing from shame, therefore, is not a cognitive process: it’s somatic. Our bodies need to learn that it is possible to feel safe in the face of shame… to feel at a physical embodied level that there is a path back to belonging. As change agents we can offer the gift of co-regulation: allowing them to experience our own calm nervous systems as an embodied experience of safety. Stephen Porges has a beautiful line here:

If you want to make the world a better place, make people feel safer… the first step is to develop a sense of self compassion in our bodies.

- Practice new behavior. Finally, we need a new strategy to adopt… and it has to be accessible to us. Lisa Lahey had a great two-part interview on Brené Brown’s podcast where she explains:

Motivation is a necessary but insufficient condition to actually change… People won’t make a change unless you find another mechanism to meet the need that the maladaptive behavior is currently serving.

Right. It’s not enough to let go of the old behavior; that is necessary but insufficient. We also need a new behavior to replace it; one capable of meeting the same need. If shame is fundamentally about belonging… this means supporting people in feeling like they belong. Friend and somatic coach Jesse Marshall summarized the research this way, reminding us that this sense of belonging must also be felt in the body:

The body will only let go of the old strategy if it is offered embodied experiences of the safety and efficacy of other strategies.

Mastering shame is a claim to power

Toxic shame is the master’s tool: we must reject it. More: we must work hard to refuse to succumb to it, and to support each other in healing from present and intergenerational trauma and the shame that accompanies it. As Daniel Schmachtenberger notes:

Unhealthy shame has been one of the most powerful tools for systemic control and oppression throughout history.

But healthy shame is one way those with less institutional/structural power can push back: to wield healthy shame skillfully is to exercise power. Jennifer Jacquet contends that shame can be a powerful tool of nonviolent resistance. She explains:

Shame gives the weak greater power.

In researching this piece I found myself returning to the literature (and Buddhist practice) of fierce compassion. The difference between healthy shame and toxic shame (for those of us trying to use shame in service of justice, to challenge entrenched systems of power and oppression) is the target. As Kristin Neff reminds us:

Call out the harm, not the people. Good anger prevents harm; bad anger causes harm.

(I would replace good/bad with healthy/unhealthy, and here anger is the expression of the “fierce” part of compassion that is calling power to account). This is one of our greatest strengths: one I have elsewhere called the righteous anger of hope we feel at injustice. This is to return shame to its pro-social role: as a tool to promote social cohesion in service of the whole, not the narrow interests of those in power (credit to Miki Kashtan for this insight).

One of my favorite contemporary examples that explicitly embraces shame as a tactic is the Swedish-initiated “flying shame” movement. It’s been personally effective in my own life: where even five years ago I wouldn’t have given much thought to air travel and its carbon footprint, now I think about it… and it’s influenced my behavior. I don’t like the sting of shame I feel at the disconnect between my values/beliefs (need to end carbon-intensive industry) and my actions. It’s an example of how a few individuals (including Greta Thunberg) can catalyze individual change by challenging an institutional/systemic practice… by appealing to our own values and exposing our already-existing but not-often-acknowledged dissonance. That feeling of dissonance motivates a reparative impulse. Koshin Paley Ellison explains:

Shame is what we feel when presented with evidence of our own hypocrisy... You’ll never be free until you can feel the pain, feel the sting of the ouch that inspires you to do better.

It also points to a key lesson: we must have alternative ways to meet the underlying need. Flying shame has been far more successful in Europe where there is a well-connected, fast, and reliable rail network… and much less successful in the car and plane-dependent U.S. It’s a fine line to walk: Cathy O’Neil argues that it’s an inappropriate use of shame if it’s not meaningfully possible to change behavior (e.g. shaming rural Americans for using pickup trucks, when they rely on those gas-guzzling vehicles to do heavy work and there aren’t available alternatives). She explains:

The principle is you shouldn’t shame somebody who doesn’t have a choice, and you shouldn’t shame somebody who doesn’t have a voice. If you do one of those things, that’s punching down.

She also cautions us against targeting individuals for systemic problems: the purpose of shame is to transform systems (and yes, the people who make up those systems), to make it easier to live in a world where everyone belongs. Jacquet explains the transformative potential:

Shame’s performance is optimized when people reform their behavior in response to its threat and remain part of the group… Ideally, shaming creates some friction but ultimately heals without leaving a scar.

Co-creating new conditions for belonging

The good news: I think there’s a roadmap to coming into right relationship with shame, to navigating the paradox that kicked off this post. I now feel more grounded: there is a way to show up with love… without letting go of the need for change. I think there is a necessary role for judgment and the skillful wielding of healthy shame: not of people as individuals, but of behavior and systems that are at odds with justice, with the demands of a world where everyone belongs.

Where increasingly I see mindfulness/social justice spaces arguing “stop trying to change people,” I want to offer a more nuanced response. Yes, stop trying to change people… but don’t give up on trying to change behavior. Justice insists that we stay in the struggle, that we continue the difficult work of inviting people—and supporting them—to transform.

The bad news: it’s a tall order. The first step alone may be insurmountable for many of us in the work of social justice: showing up with love and compassion for those whose behavior we wish to transform… is asking a lot. And it reinforces a core truth: we have to show up for ourselves first, and extend the very self-compassion we are inviting others to step into. That is the first act of transformation (I credit this framing to a conversation with Aisha Shillingford).

From that place of self-compassion, we have more agency to transform ourselves and the world. As bell hooks observed in her classic All About Love:

The more we accept ourselves, the better prepared we are to take responsibility in all areas of our lives.

Indeed, this is one definition I like defining the purpose of social change efforts generally, and the invitation to social movements in particular. adrienne maree brown puts it this way:

The invitation to create sanctuary and welcoming movements is to constantly grow people’s responsibility to transform the world for themselves and their people.

We desperately need new norms. Pro-social ways of living and relating that are conducive to a world where everyone belongs. And if we are serious about transformation, this means both co-creating and identifying those news ways of relating… and supporting others (and ourselves!) on the difficult path from here to there. To let go of old norms is to refuse to be shamed by them… to adopt new norms is to feel the sting of shame as we realize we have caused harm.

Of course this all begs an obvious question: how do we decide/agree on these new norms? As friend, collaborator, and parenting expert Jen Lumanlan put it in her in-depth module exploring shame:

If we can’t agree as a society what are the attributes and activities that should be considered shameful, how can we argue in favor of the continued use of shame?

I’ve intentionally sidestepped that question here, because so much of my other writing tackles this question directly (here, e.g.) I wanted to take up shame specifically because so often it is the biggest impediment to the kind of radical imagination I’m longing for. Too often we use it the way it’s been used against us… and it hurts our movements. This post is an invitation to step into right relationship with shame, and therefore to entertain the tantalizing possibility of returning to belonging.

As always, I’d love to hear what lands, what doesn’t, and how you’re making sense of a difficult and fraught topic. I’d love to join you in dialogue around it, in the comments below or in our next subscriber gathering.

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at building belonging

featured image taken by author : "My kids enjoying the bliss of a summer afternoon along a Norwegian fjord"

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Five Calls-to Action from the 2022 Facing Race Conference

What happens when thousands of racial justice leaders and practitioners come together after a pandemic? So much power and knowledge-sharing – and plenty of dancing and hugs, and even a few martinis!

At the 2022 national Facing Race Conference in Arizona, sponsored by Race Forward, participants were graced with gratitude for their work for racial justice, invited to be even bolder in our approaches, and instructed to avoid internal implosions at a time in which our organizations and the movement are needed the most.

I heard five important calls-to-action:

- Backlash Means We’re Winning. Keep Going!

We’re winning! The number of people of color leading and pushing change in institutions is at its highest levels. We see movement wins such as the growing people of color electorate and the halt of the Keystone pipeline. The use of the word “systemic racism” is now commonplace. We were encouraged to keep pressing forward and harder to break through on our biggest ideas. Opening plenary speakers said, “Fight for your impossible idea… and let us dream and fail.”

- Get out of Isolation. It’s Time for Reconnection!

We’ve become accustomed to quarantine and staying close to home but we were encouraged to move out of our comfort zones. Specifically, we were reminded to talk to people at their doors and to bring them back into protests and visible organizing. One speaker said, “we have to retrain people, including ourselves, to interact again, especially in person and in public.” At IISC, our mission is creating skills for collaboration and interaction. We’re exploring how we can enter and hold physical spaces with care while still centering those at risk from COVID through an equity and disability access lens.

- Don’t Underestimate White Nationalism. Expose and Bring it Down!

As distinct from the ideology of white supremacy, white nationalism is coordinated and direct action fueled by hatred and violence. Organization-building to support white racist and anti-semetic attacks and violence is on the rise and getting very sophisticated. From Boston to Michigan and Florida, leaders pointed to overt and well-organized actions in their communities from white nationalist organizations. They encouraged us to work with community organizations, government leaders, and neighbors to develop strategies to prevent their inroads and to frame messaging to drown out their discourse.

- Stop Internal Organizational Implosions. Build Organizations on Soul Work!

We heard a loud and clear call for each person inside an organization to take responsibility for extinguishing the internal fights we are waging against each other so we can focus on the external fights for justice. No organization, person, or leader is perfect so we can’t cast each other to the curb in punitive and harmful ways, stay in victimization, attack each other, and fall into gossip. They asked us to build our organizations so people can do their soul work and be liberated to do work with joy and happiness.

- Move Forward. Live into Possibility!

I was struck that you barely heard the name “Trump” around the conference. The focus was on moving and organizing for what we want and imagine. Not that we don’t pay attention to the war on our democracy and progressive values but that we go in the direction of creating even more conditions for change and living good personal lives as we do it. IISC held a workshop at the conference on fighting the return of the old normal by envisioning and leading for liberatory systems and racial justice transformation. We produced a resource guide to help you and other organizations do that while attending to the current challenges before us. Check it out.

In summary, we have power, we’re winning, and we need to reconnect and get our own house in order. Now that’s a push we at IISC appreciated and definitely needed, and maybe you feel that way, as well. We hope to see you at the next Facing Race conference in 2024.

As president, Kelly Bates (she/her) leads the strategic direction of Interaction Institute of Social Change and supports its dynamic and diverse team of consultants and trainers to meet the organization’s highest aspirations for social change and racial equity.

Kelly is a social changer, nonprofit civic leader, and lawyer who for more than twenty-five years has led advocacy, organizing, racial justice, and women’s organizations promoting collaboration, equity, and civic engagement, both locally and nationally. She strives each day to develop and embody the heart, skills, and mindset of a facilitative leader and civic innovator for progressive movement building across the country and in communities.

originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change on December 13, 2022

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

3 COLLABORATIVE PRACTICES FOR ADVANCING SOCIAL IMPACT

Learning, for me, is more than acquiring knowledge; it’s also about putting it into practice and sharing my experiences so that others can benefit from them. Below are some good practices I’ve been using for bringing people across organizations together to collectively address complex challenges, like inequality and climate change.

1) Know what you’re good at and what your partners can do better. A gathering for members of a network I was involved in sparked an idea for a ground-breaking initiative. Shortly afterwards a couple of members volunteered to take this idea forward. In addition to hosting meetings for this new initiative, network staff contributed their technical expertise. This resulted in the development of a tool institutions can use to assess their impact and prompted industry influencers to comment on its potential to be taken to scale. At the same time, participation of network staff in developing this tool diverted resources from other collaborative efforts. While ‘the juice may have been worth the squeeze’ in terms of impact, my colleagues and I learned a valuable lesson in sticking to what the network does best—catalyzing innovative ideas that members can take forward together – instead of being an implementation partner.

Jane Wei-Skillern, who has spent more than a decade researching successful networks, defines network leadership as “mobiliz[ing] various organizations and resources that together can deliver more impact rather than to become a leading organization first and then engaging in collaboration at the margins.” Communicating the network’s role in supporting collaborative efforts to members has helped maintain positive relationships.

2) Add more value to gatherings by focusing on the most powerful leverage point in the system you’re working to change. My colleagues and I once organized a gathering for industry leaders to discuss addressing a gap in progress by political leaders. Instead of a series of panel discussions about who’s doing what and debating what needs to happen next, we took an unconventional approach. This involved turning the tables on what it means to act with urgency; we invited participants to pause and reflect on their actions and to assess whether the cumulative impact of these actions were collectively adding up to the impact they wanted to make. In this highly participatory meeting, we provided the space for participants learn from their peers and to decide what changes they wanted to make in their day-to-day work as well as in how they wanted to work together.

What made this an especially powerful gathering is that it centered on practical actions that can be taken at the individual level. We challenged everyone to consider: How do I relate to my work and the people I’m working with? According to Donella Meadows, in her influential work, “Dancing with Systems,” the most powerful place to intervene in any system is our mindsets. This is because institutions, societies, and cultures are all based on ideas, and ideas originate from how we perceive the world around us and interact with it. Changing our mindset begins with self-awareness. When we’re aware of our intentions and the impact we want to make, we can consciously choose to act in ways that increase the likelihood of getting desired results.

There was also enjoyment in exploring the irony that sometimes moving faster means taking time out to pause, reflect, and take care of ourselves. If we choose to keep running ahead on the path we’re already on, without pausing now and then to check we’re going in the right direction, we run the risk of losing our way and burning ourselves out in the process. This has been an important lesson for me personally as a leader of a small team that is under continuous pressure to deliver out-sized results. I’m getting more practice in simultaneously navigating the demands of systems change and self-care; I plan to share more on this subject in a future article.

3) Provide the space for failing and learning from it. I co-facilitated a series of dialogues for organizational leaders we convened to discuss opportunities to achieve a common goal they had been working on separately. When groups come together for the first time it’s important to provide the space to get to know each other, provide information about each other’s organizations, develop a shared understanding of the problem to be addressed, decide what to do together, and to build relationships that facilitate moving ideas into action. Accomplishing all of this in a way that leaves people feeling like their time is well-spent on both personal connection and making collective progress is a tall order, and even more so when busy schedules make it hard to meet.

In this situation, I erred on trying to accomplish too much in a short period of time instead of building in more spaciousness for connection and working together over the span of longer meetings or hosting meetings more frequently. As a result, these meetings felt rushed and, unfortunately, didn’t accomplish as much as had been planned. In hindsight, I could have done a better job of communicating expectations up front and also learning more about individuals’ motivations for participating early on.

This experience brings to mind FAIL as an acronym that Abdul Kalam refers to as “first attempt in learning.” This is a helpful reminder that when we’re working on complex challenges, like inequality and climate change, it’s unlikely that we’re going to come up with the perfect solution straight away; and even when there is a good solution, it takes time to experiment with how best to put it into practice and can be taken to scale. Co-creative, a consulting firm that specializes in collaborative innovation, calls for normalizing failure as a natural part of systems change. For more information on mindsets and practices for embracing failure in systems change, check out Co-Creative’s resource.

Redefining fail as first attempt in learning is also a reminder for me to be kinder to myself when things don’t work out the way I planned. I’m also learning to extend graciousness to myself as I do for my colleagues. One of my intentions for 2023 is to be intentional in providing the space for failure within my team and the networks I work with.

Kimberley Jutze is the founder of Shifting Patterns Consulting, a Certified B Corporation that helps changemaker leaders get their colleagues on the same page and put collaborative processes in place to achieve greater impact. Her company applies organizational and human systems processes that enable organizations collaborating at the intersection of social, economic, and environmental justice solve problems that prevent people from working well together in ways that stay solved.

Originally published by SEE Change Magazine

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Creative Freedom for True Equity

Equity is often discussed, but rarely understood in a context that speaks to the core challenges of people who are under-represented in race, religion, gender, socio economic status or who may be geographically excluded and differently abled. In particular, the necessary experiences and spaces for communities within rural Texas are just beginning to receive the attention and resources required to spark conversation and change. Paying homage to deep rooted history and lineage of community members is essential for Black communities in Bastrop County, Texas (and beyond). In Bastrop, home to 13 original Freedom Colonies, the untapped power of equity-for-all lies in the centering of Blackness. In order for our society to evolve, it is imperative to recognize Black America's contributions and sacrifices as a strategy towards equity for everyone. This has been the primary focus of my personal work, which aspires to bring about social change for all.

Grappling with the core roots of exclusion and inequity, Network Weaving helps to build a framework for connection, access, support and consistent learning– a critical necessity for many who have generational ties to this local land. In Central Texas, approaching community organizing from a network weaving paradigm has supported an evolving model of rural mental health equity in many ways by building on existing culture of community-led organizing. By providing resources for gatherings and trainings for local community leaders, network weaving has become a pillar of support for the work already being done by many on-the-ground community members of these rural networks.

As a weaver, the support of this network and the ability to work collectively and autonomously alongside like-minded people has helped me develop the courage to continue down the path of creating safe spaces for Black women and Black boys. While they continue to be challenged by those who rarely experience the feeling of being othered, safe spaces continue to be places where, as Kelsey Gladwell writes, “we can simply be — where we can get off the treadmill of making white people comfortable and finally realize just how tired we are. Valuing and protecting spaces for people of color (PoC) is not just a kind thing that white people can do to help us feel better; supporting these spaces is crucial to the resistance of oppression.”

After the George Floyd Protests, people began coming to us, as community leaders to shoulder the burden of anti racist organizing, but as a mental health clinician, I saw that my community required a more communal approach that centered their mental, spiritual, ancestral and physical health. This led me to co-create a series of social wellness brunches for Black women in central Texas, a podcast about centering community voices in healing, and the Bastrop County Black Boys Collective which aims to nurture their innovation through connection with other boys and men.

Resistance has been the bedrock to creating safe spaces for local black communities, and it has often been misunderstood as an exclusionary act. Finding the courage, self-love and dedication to create from a vulnerable place has been an emancipating experience, making it hard to return back to “business as usual.” My vision and purpose, as I reflect on my life thus far, are to find ways to enhance freedom and liberation for like-minded communities. To get to this creative utopia, I often reflect and ask myself;

- How can I continue to create spaces for renewal, healing, safety, trust and belonging?

- Who understands and can support this desire for creative freedom?

- What are my strategies to unearth the core stories around me that have led to freedom and prosperity for rural Black America?

- How can we as a collective redefine “success” to allow space for our inherent goodness?

- Where and how can I build upon my connections to others dedicated to liberation?

Through my partnership with the network weaving community since 2019, I’ve been able to form lasting relationships to other community organizers, writers, and social change agents who also see a path towards healing for the communities in which they identify. Weavers are a set of individuals looking to bring attention to the causes that they are most passionate about. Working with advocates and activists dedicated to equity initiatives has been confirmation that we have much more work to do but…I am not alone.

As a Black woman, Mother, mental health strategist, and safe space creator, I’ve been able to carve out a path of healing with my community. These experiences have enabled me to have a clear awareness of those around me and the resources needed to build upon a framework of freedom, liberation, reciprocity and resilience while redefining my understanding of self within the totality of my community.

The thought-leaders within the network have remained bold, focused on serving all populations and dedicated to creating a system of social entrepreneurs with the belief that social entrepreneurship which honors the lived-experiences of community leaders and disruptors is the catalyst towards rural social and political change.

We are innovators and creators. My legacy will be the creation of a physical space for healing, freedom, and creativity for the under-represented. As an act of rebellion and love, weaving through my social change work has helped to heal my battle with power by stepping into my potential as a Network Engine, connector and artist. Weaving has become an important aspect of reclaiming my right to connect and create with like-minded individuals. I’ve already begun to witness the shift in our local narrative, relying on the voices, contributions and vast experiences of the black community.

The function, the profoundly serious function, of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, repeatedly, your reason for being. - Toni Morrison

Krystal Grimes, M.S., LPC is the President and Founder of AMMA Empowerment Services, LLC. Krystal is recognized regionally and internationally as a safe space creator and mental health strategist. Through an intrinsic ability and desire to support others, Krystal has positioned herself as a local convener and facilitator for healing and diversity initiatives, supporting the creation of inclusive and brave spaces for dialogue and innovation.

featured image by Alicia W. Brown

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

Ceremony: Reyoking the Sacred with Our Social Justice Work

“Disability is an invitation to relationship…It’s that opening that creates the whole ecosystem.”

– Sophie Strand

“Poetry is the language of the apocalypse.”

– Bayo Akomolafe1

As the newest members of turtle island, two-leggeds have always relied on ceremony for connection with, and for instruction from, older forms of sentience and the divine. Ceremonies are an essential part of all cultures across time. It is the absence of such sacred practices that results in disharmony, imbalance, and collective dis-ease. But what ceremonies and by and for whom? As social justice practitioners who come from a broad range of communities, cultures, and traditions, we often have few, if any, shared approaches for bringing together people, place, and spirit. This challenge has only been compounded during the pandemic, which has shifted so much of our work to a video screen.

While there are a number of rituals—often used by social justice practitioners—to help people connect across the virtual landscape, these tend to have more intellectual and emotional dimensions than spiritual. The increasing attention to somatic practices is expanding how we engage with one another in healthy and embodied ways, but our connection to the sacred, to sentience in its myriad of forms, to place—whether it be turtle island as a whole or a particular place on the carapace of her shell—is largely absent in our cross-cultural social change work. And it is this absence of ceremony that is impeding our ability to radically transform, as people and as a complex and interdependent ecosystem as a whole.

Members of the Change Elemental team and many others have written about the importance of inner work, of attending to the interiority of the intervener. But this work is often done separately, as individuals, or in our own spiritual communities, and not centered as much in our collective change efforts. There are exceptions of course, but these only make more stark the general absence of collective practices.

What is needed, what has always been needed, for transformational change, is ceremony—ceremonies in which we reconnect deeply with each other, with great spirit, with all of creation. In God is Red, Vine Deloria, Jr. describes the importance of ceremony for Native peoples. “The task of the tribal religion, if such a religion could be said to have a task, is to determine the proper relationship that the people of the tribe must have with other living things…” As all of creation is sentient—lizards, rocks, trees—then proper relationship is necessary with everything. And how that relationship is learned, celebrated, and restored, is through ceremony.

The healing of injustices and the restoration of aki, of the earth—including all of the creatures who depend on her and on whom she depends—requires restoring indigeneity—that is a deep connection to place, to its sacredness and interdependencies, to cultural sensibilities that are shaped by these.2 This is an individual, collective, and planetary necessity. The restoration of indigeneity requires reconnecting to indigenous practices, whether those practices are indigenous to the Americas, Africa, Asia, or Europe. For those who are not connected or actively reconnecting, this then is your task—and yes, it can be complicated, painful, and messy. It is an extension of inner work, of cultivating the ability to be present to what is and was and then draw on this ability to help create what will be.

And too, when we come together as change makers, we must hybridize and invent new ceremonies to support our current collection of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic beings—all while centering the primacy of the indigenous world in which we are currently walking. It is a potent task, but not without antecedents.

The evolution, resistance, and resilience of indigenous spirituality in the face of settler colonialism and the middle passage provide some clues for how we might accomplish such transgressive divination. And while these adaptations were the result of subjugation and duress, our current times—the extraordinary amount of injustices we are quite literally buried in—necessitate another sacred leap in order for us to work collectively together.

So, how do a diverse group of social justice practitioners develop and practice ceremonies together? One answer can be found in Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer: