Power of Networks: Interconnectedness Drives Change

Our world is beset by societal challenges that are large, complex, dynamic and highly contextual. Networks can play a transformative role in resolving these challenges by sparking an interconnected web of actors and actions. Catalysing networks is key to enabling a sustainable ecosystem with diverse actors who have the capability to sense, synthesise and respond to societal problems by varied means – both normative and descriptive.

Networks are about relationships and interactions between actors in a system. Interactions can be of any type (e.g., consumes data, creates content, conducts workshops, etc.) which allow us to harness natural community responses and bridge the distance between those who need and actors who can.

In this 90 minutes webinar, Sanjay Purohit, Chief Curator – Societal Platform at EkStep Foundation, discussed the Power of Networks and covered:

- The importance of network effects and the view of a network as units of interactions – moving from 1:many interactions to many:many.

- The need to facilitate interactions between and within formal and informal networks, involving state, civil society and markets, to catalyse large-scale systemic change.

- How can digital platforms amplify the impact of these interactions and enable societal change at scale?

Sanjay Purohit, Chief Curator - Societal Platform, EkStep Foundation talks about the Power of Networks.

Originally published at Societal Platform

co-creating pathways for a resilient society

Societal Platform is a community of curators, catalysts, and network weavers. We pool our individual strengths and channel our collective imagination to enable social change leaders to advance their missions.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

6 Tips for Making Online Collaboration More Productive and Engaging

In reflecting on a meeting I helped organize for a multi-organization, multi-stakeholder network, I realized that there’s more to online collaboration than using the right technology and best practices.

In July 2020 a survey was conducted by Collective Impact Forum about how collaboration has changed as a result of the combined effects of COVID-19, a prolonged economic downturn, and racial justice uprisings. Almost half of the challenges most commonly identified involved new ways of working together and relating to each other in an online environment. These included difficulty adapting programs to a physical distancing context, lacking the quality of experience that comes from working together in person, and encountering Zoom fatigue.

For our online meeting, an intimate experience was created by inviting attendees who faced similar challenges. Ground rules were set at the beginning of the meeting to provide a safe space for open dialogue. Network members modeled trust-based vulnerability by sharing pivotal experiences that led to broader change in their organization. Guided small group discussions enabled participants to connect with each other on a deeper level. Through an action learning approach participants gained valuable insights and identified solutions to challenges faced in their work. A break mid-way through the session provided an opportunity for everyone to step away from their electronic devices to rest and re-charge.

It takes a village to create an online community

A successful online meeting takes support. Although we often think of support in terms of tangible elements, like technology and best practices, they are insufficient on their own. There is also a human dimension to support systems that often doesn’t get talked about—unless things go wrong. What ultimately made the difference in this situation was the formation of an online meeting production team whose members were committed to achieving the same goal. Demonstrating effective collaboration behind the scenes contributed to a successful online meeting and a stronger team.

Tips for making online collaboration more productive and engaging

1. Assemble a team and bring them together early on in the planning process

Days before the online meeting the organizers realized they needed a bigger production team. Having good relationships with her co-workers made it easier for the facilitator to quickly bring a few additional people on board and orient them to their roles. Identify the different roles needed for your online meeting in advance and recruit people to fill them. Limit the number of tasks (e.g., facilitation, note taking, time-keeper, managing the technology platform, monitoring the chat, etc.) each person is expected to do so that multi-tasking doesn’t result in important details falling through the cracks. It’s also a good idea to have a back-up person whose primary function is to be ready to step in if a team member needs additional support.

2. Allocate more time for organizing online meetings

Planning for online meetings often takes longer than in-person meetings because of additional factors to be considered. Think through in advance how the meeting will take place, from start to finish, beginning with the purpose. How will you structure the meeting to accomplish your goals? How will you enable participants to actively participate? How will you support the meeting production? Help team members work together instead of assuming they will figure out what needs to happen and how to get it done on their own. This involves making sure people understand their roles and what is expected of them. Provide team members the resources and any training needed to accomplish their tasks. Determine in advance how team members will communicate with each other during the meeting, such as through texts, to share information, address problems, and make decisions.

3. Create a valuable experience for everyone

In addition to creating the content for your meeting, plan in advance the kind of experience you want to create for participants. How will you welcome people as they enter the online meeting room? Greeting each person by name as they arrive can help set a welcoming tone. How will you engage people in the conversation? Some examples are using polls, providing opportunities for people to ask questions, and building time into the agenda for reflection and sharing insights. Mixing people from different industries and sectors in virtual breakout rooms allows for conversations they wouldn’t ordinarily have that can potentially lead to breakthroughs in solving problems. Creating the space for networking, such as by randomly assigning people to breakouts, can foster spontaneous collaboration. Design your meeting so that in addition to advancing collective goals, participants come away with ideas, insights, and resources they can use in their own work.

4. Practice makes better

To ensure your online meeting runs smoothly, create a “run of show” document that explains in detail what will happen from start to finish. This includes estimated times for each section of the agenda, what resources are needed, and what tasks each team member is doing for each segment of the meeting. Organize run throughs for both speakers and the meeting team to help prepare them and test the technology. Run throughs can also foster teamwork by encouraging people to contribute their ideas for improving the meeting as well as giving and receiving help.

5. Invite people to bring their whole selves into the room

Online meetings can also serve as opportunities to engage people in a variety of ways. Design your meeting to offer more than a learning experience. Create the space for people to engage with their hearts (connect with each other on a deeper level by discussing what really matters), hands (make something together, like an action plan), and spirit (align around common goals, action items, or next steps). To learn more about this approach, check out Co-Creative Consulting’s 4 Agendas in Collaborative Innovation.

6. Create the space for learning on multiple levels

After your online meeting organize a debriefing that includes speakers, facilitators, and members of the production team to capture lessons learned about how the meeting went and the experience of working together. This can be as simple as taking turns answering these questions: What worked well? What can be improved upon for next time? Create the space for personal growth by inviting people to share what they learned about themselves from this experience.

My takeaway from working with networks in an online environment is that successful collaboration is as much about what happens behind the video camera as in front of it.

Originally published at See Change

featured image by Chris Montgomery on Unsplash

Kimberley Jutze is a social activist and founder of Shifting Patterns Consulting, a Certified B Corporation that helps changemaker leaders work better together to achieve greater impact. She specializes in helping networks and other collaborative groups increase their productivity and engagement. You can follow her on Twitter at @ShiftPatConsult and LinkedIn

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

A Journey Toward Becoming an Anti-Racist and Multicultural Organization

A note from the editor: This post is a letter sent on April 16th from The Wallace Center at Winrock International to it's friends and colleagues. Network Weaver asked to republish this letter, and the accompanying resource, because, like The Wallace Center, we also see the potential for transformational impact in sharing a story of awakening to organizational inequity and enacting systematic change. The authors write: "By sharing our own story, we might encourage others to interrogate their own blind spots, rebuild new systems and processes that prioritize equity, and shift organizational cultures"

A couple of years ago, our team at the Wallace Center undertook an honest assessment of our organization’s history, values, culture, operations, and programs to determine where we landed on the Continuum on Becoming an Anti-Racist Multicultural Organization. What we realized and learned through that reflection was painful and real, but it marked the beginning of our continuous efforts to learn, grow, and center racial equity in our organization and work.

In the spirit of accountability, vulnerability, and transparency, we want to share the Wallace Center’s Journey Toward Becoming an Anti-Racist and Multicultural Organization.

Unfortunately, the timing of this message coincides with the continued brutality against Black and Brown people at the hands of the police. This week's news reports out of Minneapolis about Daunte Wright's murder and Derek Chauvin's ongoing trial demonstrate the urgency for systems change. We will never achieve economic, environmental, and social justice without first achieving racial justice.

Learning from our past.

For decades, the Wallace Center didn’t acknowledge or address the historic and current racism that underpins our farming and food systems. We sat on the sidelines, and our passivity and complacency reinforced racism and racial inequity in the food system and in the movement to change it. Partners and funders substantiated this hard truth; that we as an organization had a lot of work to do to meaningfully center racial justice and equity in our food systems change work and dismantle white supremacy culture within our team and parent organization, Winrock International.

That reflection marked a turning point for our team. Since 2017 we have been in process to put our intentions of being a racially-just organization into practice. This has been and continues to be both a personal and organizational journey for our staff. As a predominantly white team within a predominantly white organization – historically and today – we undertake this work with a sense of humility and from a position of learning rather than knowing. Institutional inequity and white supremacy is deeply entrenched in our organizational structures and systems and is pervasive in the domestic non-profit field as well as the international development sector we are embedded within at Winrock International. This includes not only our own organization, but also those with whom we affiliate, including those who fund our work.

Moving forward, together.

This document provides a summary of our journey thus far towards centering racial justice and equity in our organization in a meaningful, authentic, and accountable way as embodied in our racial equity commitments. There are many resources linked throughout the document that have been instrumental in fueling our internal work and we hope this will be helpful for others. It is not a “how-to” guide – we are not experts in advancing racial equity in organizations – but rather a perspective of how we’re taking steps to undo racism in our organization. One such example is through the Food Systems Leadership Network’s Network Weavers conversations, in which members virtually connected to discuss ways in which our work could contribute to and advance systems change.

We can’t do this work alone.

Our learning journey has been encouraged and supported by the work of other organizations and leaders who have inspired and challenged us. We have kept much of our process and learning internal to the Wallace Center and our parent organization, Winrock International, which has more recently started the work towards equity. It is our work to do. After the killing of George Floyd last year, followed by the international uprising against institutional and structural racism, we felt that our Wallace Center journey could be a helpful reference for Winrock International and other (mostly white-led) organizations who are reckoning with their own complicity in perpetuating white supremacy and racism. By sharing our own story, we might encourage others to interrogate their own blind spots, rebuild new systems and processes that prioritize equity, and shift organizational cultures. We also agreed that sharing our journey and our commitments publicly would enable others to hold us accountable as we work towards becoming an authentic and explicitly anti-racist organization.

We want to specifically thank The Justice Collective for their partnership and support of our team, and honor the hard work and commitment of each staff member at the Wallace Center who has contributed to our evolution. We are still very much in the thick of it – the journey toward our collective liberation has no endpoint – and invite your feedback, reflections, and questions.

In solidarity,

Susan Schempf and Pete Huff, Co-Directors, Wallace Center

The Wallace Center develops partnerships, pilots new ideas, and advances solutions to strengthen communities through resilient farming and food systems. We serve the growing community of organizations, businesses, and public agencies involved in building a good farming and food system in the United States. Our program work focuses on advancing collaborative, regional efforts to grow and move good food – food that is healthy, regeneratively produced, and recognizes and builds value across the entire supply chain, from producers to farm workers, aggregators, processors, distributors, buyers, and the community based organizations supporting the food ecosystem.

featured image found HERE

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

by Susan Schempf and Pete Huff, Co-Directors, Wallace Center

Patterns of Collective Flight

This article is dedicated to my fellow super-connectors, movement weavers, story activators, and of course, visionary poets and meta-pattern identifiers — all of whom are seeking to create a more just and equitable world. They include: those who design new economies and value exchanges through open innovation and knowledge sharing; those who strategically connect and relation-build; those with balanced local and planetary perspectives; and those who shape regenerative solutions.

We are like the starlings who fly in free flowing formation — though the micro story patterns continuously change, we sense the emergence of a grand unified story field as we learn to cross boundaries, take creative action and fly together in one movement.

Fight or Flight

Murmuration is a great metaphor for social change. Some of the best lessons for collaboration are found in the dynamics of living systems. Who hasn’t been mesmerized by the graceful beauty of a starling murmuration? The metaphor reveals an intuitive sensing of change, both subtle and strong, in our collective heart and mind. Our inward navigation guides us to move with others who are imagining and implementing whole-systems symmetry.

My personal flight paths are often found on the liminal edge, and many of you have graciously drawn me into your circles of flight. You’ve enticed me by your creative systems imagination and welcoming appreciation. Subtly and fluidly, our flight paths flow together to harmonize in story patterns. Our multiple perspectives converge into unified vision. If one clarifies or changes their intentions, even slightly, big shifts in collective flight patterns can change an entire systems trajectory.

Murmuration reveals a dynamic living systems dance. The starling flocks shape-shift in a swirling aerial ballet while maintaining cohesion as a group. In unison, they conduct evasive maneuvers in uncertain environments often sparked by the presence of a predator species.

This dance is achieved by interacting with six or seven of one’s closest neighbors, optimizing the balance between group cohesion and individual effort. If one bird affects its seven closest neighbors, then each of those neighbors’ movements affect their closest seven neighbors through the flock. This is how a swarm becomes an intelligent cloud traveling in many directions, at various velocities.

Murmurations optimize a form of agility, neural transmissions or signals of shared information which elegantly transcend our rigid organizational diagrams attempting to define self-organization. Like passages of time and music, we resonate at deep levels of universal beauty and symmetry, understanding in ways that transcend explanation.

The science of synchronization

But for those who prefer scientific analysis, Jaymi Heimbuch talks about the science of synchronization at Mother Nature Network, “the secret lies in the same systems that apply to anything on the cusp of a shift, like snow before an avalanche, where the velocity of one bird affects the velocity of the rest.” This is known as “scale-free correlation,” and every shift of the murmuration is called a critical transition. Giorgio Parisi, a theoretical physicist at the University of Rome, lead a research team looking into the amazing movement of starlings and published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2010:

“The change in the behavioral state of one animal affects and is affected by that of all other animals in the group, no matter how large the group is. Scale-free correlations provide each animal with an effective perception range much larger than the direct inter-individual interaction range, thus enhancing global response to perturbations.”

Jaymi points out,“Because the size of the flock doesn’t matter, a huge flock is able to respond to a predator attack as effectively and fluidly as a small flock. No matter the size, the system works. If one bird changes speed or direction, so do the others. The question remains, however, how does an individual bird spark a change if all are busy responding to the movement of everyone else? And more importantly, how do they do it so incredibly quickly?”

And for systems geeks

Murmurations are a compelling visual representation of “complex adaptive systems.” They self-organize a spontaneous emergence of new patterns, causing adaptive reorganization. The shapes or outcomes cannot be determined since they are not designed from the “outside” (as are most human systems), but are adaptive to the flock itself.

According to systems scientists, because of their ability to process and create information, complex adaptive systems can change their behavior, co-evolve and adjust to new rules that govern relationships with their surrounding environment. These systems are sensitive enough to undergo rapid and unpredictable transformations while they seek to maintain stability and balance in the midst of internal and external fluctuations.

Murmurations also represent systems known as “edge of chaos systems” which are full of creative novelty and experimentation. These systems react to small changes in unexpected ways, communicate instantaneously, and gracefully maneuver unpredictable shifts in direction when responding to predators or roadblocks.

According to John Cleveland’s Complexity Theory — Basic Concepts and Application to Systems Thinking, “A vibrant democracy is an ‘edge of chaos’ form of governance; a healthy market is an ‘edge of chaos’ form of economics; a flexible and adaptive organization is an ‘edge of chaos’ institution; and a mature, well-developed personality is an ‘edge of chaos’ psyche.” He goes on to explain that many systems involve a closed or rigid order which make them incapable of adaptable systems evolution.

Indeed, complex adaptable systems, like nature’s systems, are abstract and thrive in perpetual motion. To some, these systems pose a threat and need to be controlled, harnessed or exploited. History is rife with tension between hierarchical social control (think mechanistic technologies, monopolies, dictatorships) and decentralized, “edge of chaos” systems.

But the great equalizing force between seemingly incoherent chaos and rigid order ideally meets somewhere in the middle on common ground. This is the sweet spot, where new regenerative systems have the opportunity to tap into the creative force of edge chaos (artists thrive in edge chaos systems btw), causing adaptive systems to grow, learn and evolve.

The open knowledge and story platforms set a table — a feast for resource exchange, cooperation, dreaming and making meaning. The collective flight allows for fluid moving between disciplines, sectors, siloed thinking. We become part of a dynamic “murmurating system” that leverages uncertainty while maintaining a form of consensus; a sublime coordination that consistently transitions from scattered chaos to identifiable patterns. And as we seek to learn and make meaningful connections outside of our immediate flocks, the entire pattern shifts.

Synchronization is poetry, poetry is art. Art has always been a more productive use of energy than the “fight”. The cool news is that living systems cannot be controlled by hierarchies or individual parts. Living systems are adaptable whole-systems that seek symmetry, beauty and balance.

As each of us becomes more adept at processing information that is attuned to deeper universal patterns, we can adapt by intuitively navigating complex system realities. We can not only adapt but fly, riding the air currents to higher heights while weaving new story patterns and harmonizing our aligned efforts.

Originally published at Medium.com

Thea La Grou is a visual communicator who occasionally uses words — a “creative entrepreneur,” artist, media alchemist and producer collaborating with cultural creatives, systems architects, and networked movements. She is Co-founder and Marketing Director at Millennia Music & Media, FPC, Founder and Executive Director at Compathos Foundation and is an Edmund Hillary Fellow. Author, speaker, and event producer — Thea specializes in crafting experiences that harness the shifting nuances of storytelling and bring people together to find meaningful action around the common good. Her latest ventures include TwelfthMuse, IMERSIVstorylab, and Films for the Planet— the best in environmental and social action films on demand.

________________________________________

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Leadership and Community in a Time of Transition

In communal transformation, leadership is about intention, convening, valuing relatedness, and presenting choices. It is not a personality characteristic or a matter of style, and therefore it requires nothing more than what all of us already have. This means we can stop looking for leadership as though it were scarce or lost, or it had to be trained into us by experts. If our traditional form of leadership has been studied for so long, written about with such admiration, defined by so many, worshipped by so few, and the cause of so much disappointment, maybe doing more of all that is not productive. The search for great leadership is a prime example of how we too often take something that does not work and try harder at it.

Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging

As a white man born into a well-off and well-educated family in the US, the idea that I might step into leadership was part of my conditioning. And as someone who has chosen work that involves issues of justice, equity, and inclusion, I find myself challenged to re-evaluate the very definition of leadership. In this, I have found two books to be particularly helpful. Reading Peter Block’s Community: The Structure of Belonging in 2010, I was struck by his declaration that “leadership is convening,” and by the concrete guidance he provides for living into that story. Some years later, I was further inspired by Frederic Laloux’s description in Reinventing Organizations of a new paradigm for governance, his addressing of questions related to hierarchies and self-organizing, and his vision for what might be possible as we continue to evolve our capacities for new forms of organizing. Both authors start from the premise that our conception of leadership in the dominant Western culture is failing us, opening the way to new approaches based on “power with” rather than “power over.”

I was brought up within that dominant culture as one of its most privileged members, and was taught to excel in things like critical analysis and debate. Then in 2010, I found myself called into work inspired by a new possibility that I suddenly recognized: we could make powerful use of our new virtual capacities to convene large groups of people by engaging them in generative dialogue about systemic transformation. I found that my old training did not serve me and was in fact a handicap in many respects. At the same time, I discovered that I had gifts for creating and holding hospitable space, listening deeply, and making meaning out of the diversity of opinions, beliefs, and worldviews that were being expressed in the conversations I helped convene. Block’s work offered both a powerful validation of this new direction and a road map for the journey.

Around the same time that I was reading Community, I had the delightful experience of shifting my story about myself. I had worked with a professional career consultant a few years earlier and had tested as an introvert (INFJ) on the Myers-Briggs personality inventory. Then one day while driving home and mentally preparing for a World Cafe conversation I was about to host online, it struck me that the excited energy I was feeling was characteristic of extroverts. So I immediately called my friend David, a Myers-Briggs maven, and asked him to look up the characteristics of the ENFJ personality. The answer? That people like me are leaders of groups, and that others are drawn to participate in those groups not because of efforts we make to persuade them that they should do so, but simply because of the way we show up. In Block’s words, this is “invitation as a way of being,” where the artist replaces the economist/salesman.

As I reflected on why I might have scored as an introvert, it occurred to me that I had exiled my gifts as a convener of hospitable space. My explanation for having done so was that, throughout my early adulthood, my efforts to show up as a whole person were not well received. So I told myself the story that I preferred my own company and a small set of close relationships, and that being in groups was a challenge for me because of my nature. Accordingly I made my professional world a small one, holding back on what I felt called to most deeply. Reflecting on this anew, it occurred to me that I had intuitively sensed the bankruptcy of the dominant paradigms through which I had been told I was supposed to engage with the world, and that the painful experiences in my work were the result of my rebellion against operating in that context. The discovery of this new way of showing up--as a convener of groups, in service to movements for transformational change-- was utterly liberating.

The other inspiration I drew from Block was the idea that community is required for transformation. It is not enough for us to work on ourselves in isolation. As Thich Nhat Hanh has famously said, “the next Buddha may be a sangha.” And so I embraced the creation of community as a core purpose of my work. I came to see the emergence of social fabric made up of many interwoven relationships as being the most important outcome in any engagement, over and above the conversational content or action planning that often provides the explicit context for a gathering.

The places where we live are failing to provide a strong sense of community for many of us. Other traditional markers such as nationality, ethnicity, gender, political ideologies, extended family structures, etc. also often do not seem sufficient or lack resonance. As a result, we are witnessing the increasing fragmentation of identity, accompanied by a yearning for belonging and connection to replace what we have lost. The dangers of this phenomenon are apparent all around us, most prominently in the political realm, as a product of the broader challenge of simply identifying a shared reality. As we all struggle with the fact that conventional wisdom has shown itself to be incomplete, flawed, and sometimes false, many are choosing to embrace conspiracy theories--a phenomenon that I believe to be toxic. Yet I also see a great opportunity in this unraveling--a chance for humanity to go through a kind of reweaving (or re-wilding) that builds upon what was good and important about our previous stories and forms of identity, yet also transcends the limits they carried with them.

As we co-create new forms of community, we get to try out identities that connect us directly to our gifts. Anthropologists have determined that the natural size for a tribal unit is a little less than 160 people, and that the “gift economy” was the original form of organization that we employed in such groups. I love to imagine what a group that size can do today with the power of our new technologies, if it succeeds in fully bringing forth the gifts of its members and releasing them into the world. And what might be possible if these “tribal groups” learned to connect and collaborate with one another, based on natural alignments in purpose and values? And then what if we learned to do this in a way that reconnected us to the earth as a whole, by linking together our care for each of the places where our feet touch the ground?

This vision of transformational communities requires a good deal of coordination, collaboration, and co-creation both within and among groups. So it is not surprising that the crucial need for wise and effective governance has emerged in my work time and time again. Tom Atlee, my first mentor in the convening work I began in 2010, introduced me to the concept of collective intelligence and to a wide variety of processes that have been developed for tapping into it, including many that relate to governance and decision-making. His new Wise Democracy Pattern Language is a wonderful resource, as is the Co-intelligence Institute website he curates.

The need for governance structures became more tangible for me when I co-launched Occupy Cafe and was exposed to consensus decision-making and Sociocracy. Not long after that, I became part of the core team for the Great Work Cultures initiative and was also introduced to the Future of Work movement, both of which focused on new paradigm approaches to decision-making and sharing power in the workplace. Another influence was the concept from The Circle Way of “a leader in every chair.” And the related idea that movements need to be “leaderful” rather than “leaderless” came from Peggy Holman, whose book Engaging Emergence also taught me practical and inspiring approaches to convening. Then in 2014 I read Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations, which seemed to pull it all together.

Like Block, Laloux presents models for organizing ourselves using “power with” rather than “power over.” In his synthesis based on the study of a wide variety of organizations, he identifies three key innovations: evolutionary purpose, self-organizing, and the welcoming of our whole selves into the spaces where we work. He gives examples of each of these patterns happening in a number of organizations, while also stating that he has yet to see any instance where all three are present in a single one. Since he wrote his book, many people--myself included-- have been inspired by his observations (and those of the many others working on similar visions of “next stage” organizations) to attempt to co-create initiatives that have all three of these elements in their DNA.

One of the interesting patterns I've observed in groups that take up this challenge has to do with hierarchies. Because our old models have failed us so dramatically in so many respects, there is now a deep mistrust of leadership. And because so many voices have been marginalized for so long, there is a need for them to now be heard. How we learn from these experiences in order to create spaces where we thrive can be a tricky thing.

I remember vividly my visit to the Occupy Wall Street encampment in New York City in 2011. I was particularly struck by the general assembly I witnessed that day. There was a problem to deal with: a giant pile of dirty, wet laundry had accumulated as a result of several days of rain. It was beginning to mildew. Someone had already secured a truck and located a laundromat uptown that would welcome them. All that remained was for the group to decide to allocate money for the laundry machines. There were easily 150 people participating in that deliberation. It took over an hour (using the famed “people’s mic”) to hear everyone who wished to speak and to decide that yes, the money should be released so that the laundry could get done. While many might have seen this as something less than good governance, I chose to interpret it as a kind of communal poetry!

It is crucial that we create spaces for collective expression that allow all voices to be heard. Peter Block gives us one model for doing so in a way that weaves community and brings forth our gifts. His approach creates a context of relatedness, trust, commitment, and the safety to dissent. These are crucial precursors to sharing power well, but we also need structures and processes designed to support us in making decisions together in a good way. A key pattern for doing this, as Laloux found in his research, is the empowerment of small groups closest to the work that needs to be done as the vehicle through which authority is allocated. As Block also declares: “the small group is the unit of transformation.”

When needed, small groups can seek input from the whole community or organization, and can also reach out beyond it to all stakeholders, if desired. We have lots of great methods for this kind of "advice process," not to mention talented facilitators who love this kind of work. But it still makes sense in most cases for a small group--people connected to the needs being addressed and the consequences of their choices-- to process that broader input, make an appropriate decision, and then stay engaged and agile in order to respond to what happens as a result. Sociocracy works in this way, and I am very drawn to that methodology, although a full implementation of all its elements may not be the right answer in many cases. Indeed, I don't believe there is a one-size-fits-all solution, and I think that we are still very much in the beginning stages of figuring out how to do this well. This is especially true to the extent that we wish to transcend the organization as the core unit through which work must be done, returning to communities as the way to meet many more (and perhaps even most) of our needs.

The context in which these questions about leadership and community have the most meaning for me is the possibility of near-term civilizational collapse. Though Jem Bendell has become perhaps its most prominent voice today, Meg Wheatley was the thought leader I first paid attention to who was preaching this gospel. After many years of working to support the emergence of a new paradigm for humanity based on the idea that “whatever the problem, community is the answer,” Wheatley had a change of heart, giving up on the idea that we could still “save the world.” In her 2012 book So Far from Home and the subsequent Who Do We Choose to Be? she painted a stark picture of despair among many who, like her, had worked for decades to bring forth a world that works for all beings. Now she spoke instead of the need for leaders to create “islands of sanity” amidst the sea of collapse.

Is Wheatley right? Joanna Macy, the contemporary of hers who popularized the term “the Great Turning” to encompass the magnitude of the civilizational shift they and others were imagining, says that we still don't know whether it is too late for us to midwife that better world or not. I find her view to be compelling as well. This brings me back to Block, who emphasizes that the story we choose to tell ourselves is just that: a story and a choice. And that the choice we make has payoffs and costs.

And so I will close with a story I choose to tell myself. Holding onto it gives me the payoff of validating the community weaving work I feel called to do, and my sense of having found a good way to be a leader. It therefore helps me to minimize the guilt I hold onto for living a privileged life, including not doing more to dismantle the systems of oppression I benefit from, and choosing to have an environmental footprint that is way bigger than my personal fair share.

What are some of the costs of my attachment to the story? One is that I may not be paying attention to other possibilities for making use of my gifts. Another is that my sense of self worth and identity is dependent on outcomes I often cannot see and must take on faith. A third might be that I have fooled myself into believing that I am practicing “power with” when in fact I am perpetuating the old patterns of “power over.” Furthermore, this story leaves me open to the criticism that I am a “virtue signalling” hypocrite because, while I claim to be a stand for the need to transform our ways of doing things so that we reweave rather than unravel our environmental, social, and spiritual life support systems, I am choosing a life of privilege that contributes to that very unraveling.

For now, knowing all that, I am sticking with the story...

There may not be much difference between the work of creating islands of sanity and of reweaving the whole world. It might “simply” be a matter of tens of thousands of transformationally empowered communities, each doing powerful work in their own local domains (be they place-based or virtual) while also supporting one another to bring forth a global shift. For all we know, just as the mycelial mat is hidden from our view and has only recently come to define our basic understanding of how a forest works, a sufficiently dense weaving of relationships, flows of information and resources, and connections to other parts of the transformational ecosystem might already be underway such that tens of thousands of these communities are springing up around the globe, mushroom-like, in order to nourish us, transform our collective consciousness, and cast billions of potent spores to the winds of change.

*Published in the Sharing Corn Journal, Volume 2, available from Joy Generation in print form here and in digital form via Amazon here.

featured image found at WSJ.com

Ben Roberts is a systemic change agent and“process artist,” working in service to what Joanna Macy and others have called "The Great Turning." Inspired since 2010 by the internet’s largely untapped power to convene and support new modalities for participatory dialogue, he has been a pioneer in bringing large group conversational processes into the virtual realm via platforms such as Zoom and Slack, and in blending and creating synergies between virtual and in-person engagement.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

From Nature’s Mutualistic Networks to More Resilient Human Networks

We have been taught to live in a competitive, survival-of-the-fittest world. But what if this has been wrong? What if the natural world, and the humans in it, are much more cooperative than competitive?

The idea of the survival of the fittest originated in Darwin’s Origin of Species, and his theory of natural selection. Sure, natural selection does have a role to play in evolution, but it might not be as important as we had previously thought. In fact, some scientists assign it a weight of just 1 out of 10 concerning the evolution of certain processes, such as the evolution of the anatomy of species[i]. Other scientists suggest that evolution should not be considered in terms of species as separate from its environment, but at the level of the system itself (species + environment). Looking at it from this perspective, they maintain, is much simpler and governed by a much smaller set of laws, than analyzing the evolution of elements by themselves[ii].

We can find examples of mutualism and cooperation all over the natural world, from pollinators and plants, to animals and the microbes living in their guts. And in many cases this cooperation is not merely optional, but essential to life itself. Certain plants will not grow in soils where you cannot find a specific type of fungi, since they need to form a relationship with it in order to survive. Lichens are an association between a bacterium and a fungus. They are an organism that is an association of two different life forms, contradictory as the notion may seem. Trees communicate with each other through a network of mycorrhizae, a fungal structure invisible to the naked eye that connects their roots, transporting nourishment, messages and even teachings (yes, plants have cultural transmission and are able to learn from their neighbors)[iii].

And the human species is no exception. We have more bacteria living in our gut than we have cells in our bodies, and they influence our health, our moods and even our behaviors[iv]. Without them, we cannot survive. (Not to mention the fungi that live basically everywhere and the microscopic mites on our skin.) We are not just a single organism; we are a small cosmos of organisms. And like all other species, we are not meant to just compete, but to cooperate harmoniously with those around us.

What is conspicuous about cooperative interactions in the natural world is that they happen in networks. This a very familiar word in the human lexicon, since we network for just about anything: for business, for trade, for information exchange. What can we learn from these well-functioning natural cooperative networks that we can apply to our human ones, so that they are more resilient?

First of all, if we take a look at mycorrhizal networks in old-growth fir forests[v], we find that young saplings are established within the networks of veteran trees. Usually, the larger the trees (and the more resources they have), the more well-connected they are within the forest network. This highlights the importance of large mature trees in the architecture of the network, which have long life-histories of connection. Greater establishment of young saplings have also been shown when they are linked into the mycorrhizal network of larger trees. The lessons to learn from this are quite simple: if you have more resources, share them, and you will help others flourish. Also, we need multigenerational human networks: elders have a lot of wisdom to impart, and if youngsters are connected to them to “absorb” it, they are more likely to thrive.

The forest networks also have what we call small-world properties, meaning that individuals are closely knit together, and that you do not have to go through many to get from any one individual to another. Simple enough as well, right? Do not isolate yourself, if you connect and collaborate with others, you are also more likely to thrive in your community.

Forest network symbiosis is not just an affair between two or more organisms, but a complex assemblage of fungal and plant individuals that spans multiple generations. In them, fungus species form “living links” connecting trees and allowing them to communicate and exchange resources, and benefitting from the exchange as well. In our networks, human connections do not have to be strictly restricted to flows of information or products, they can be other people (facilitators, teachers, networkers), living links that enable effective exchange of any kind between other people or groups.

Last but not least, these networks are robust to perturbations, but fragile to the targeted removal of the “hubs”, large mature trees. If elders are left out or removed from contributing, the whole ecosystem is more likely to collapse.

So far, we have been looking at relatively simple networks, connecting individuals of a few species only, and belonging to the same forest “group”. Now let’s take it a step further and take a look at networks that involve far larger numbers of species interacting. And at the same time make an analogy with different “species” of organizations trying to cooperate.

There are several types of networks in nature, and they are of two main types: antagonistic (e.g: food webs, parasitism) and mutualistic (e.g: pollination, seed dispersal). A study by Thébault and Fontaine[vi]analyzed several characteristics of both types of networks, focusing on pollination (mutualism) and food webs (antagonism), to find out what made them more persistent and resilient. They found out that the two types of networks behaved quite differently.

While antagonistic networks benefit from being modular (having subgroups that interact heavily amongst themselves and very little with other groups – does that sound familiar?), the cooperative mutualistic networks that we are interested in were strengthened by a nested structure. This means that there are a lot of “specialists” in the network, interacting with subsets of the group that “generalists” interact with. At an organizational level, “generalists” are larger organizations that have several areas and a wide range of action, such as groups focusing on governance and policy, and can interact with many other smaller, grassroots “specialists” focusing on one or two areas of action. How do we ensure the nested structure in a human network? We make sure that there are no local groups that are isolated from the world at large and from larger spheres of power. The smaller grassroots organizations and groups can (and should!) cooperate with each other at a local level, but not without being connected to larger organizations that ensure that they have a voice at a regional, national or global level.

Another study[viii] provides even more lessons to be learned from nestedness: it not only helps to reduce competition and increase the number of coexisting species, but a nested structure like this is likely to arise by itself, as long as new species enter the community at the places where they have the least competitive load. When a new group wants to cooperate, welcome it in the place where it is most needed, where the skills and value it provides are most lacking, and take the best advantage of the complementarity!

Mutualistic networks tend to have one other characteristic in common, which is related to nestedness: they are asymmetric. There are a few “generalists” and a whole lot of “specialists”[ix]. The generalists interact with each other, but also with the specialists. A lot of grassroots activity is good: but so is getting the word out there about your work and spreading local solutions to the global level—”Think Global, Act Local”.

The final two things that increase persistence and resilience of networks are two very simple ones: high diversity and high connectance. Diversity is self-explanatory, and quite obvious. High connectance means that a high percentage of the possible links are materialized, so also at this level, connect and collaborate as much as you can (within reason), and the benefit for all will be increased.

And here is a bonus lesson: a study by Evans et al.[x] that analyzed the interconnectivity of networks on a British farm reached a very interesting conclusion. Two habitats that were not very representative in terms of area were disproportionately important. This gives us a clue that there may be groups out there with skills and areas of action that still tend to be overlooked at the grassroots and even the governance level (tipping my hat to the ethical technology and governance folks), but whose work others will rely immensely upon to be able to keep the integrity of the network.

But this is not the end of it: stay tuned for the multilayer nature of ecological networks and how to apply its lessons to community organizing!

[i] Lewin, Roger (1993) Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos. Phoenix, Orion Books, London

[ii] Lotka, Alfred (1925) The Elements of Physical Biology. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore

[iii] Simmard, S. W. (2018) Mycorrhizal Networks Facilitate Tree Communication, Learning, and Memory. In: Memory and Learning in Plants. Springer International Publishing, AG

[iv] Gilbert, S. F., Sapp, J. & Tauber, A. I. (2012). A Symbiotic View Of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals. Quarterly Review Of Biology 87(4): 325-341

[v] Beiler, K. J. et al. (2010) Architecture of the wood-wide web: Rhizopogon spp. genets link multiple Douglas-fir cohorts. New Phytologist 185: 543–553

[vi] Thébault, E. & Fontaine, C. (2010) Stability of Ecological Communities and the Architecture of Mutualistic and Trophic Networks. Science 329: 853-856

[vii] Palazzi, M. J. et al. (2019) Online division of labour: emergent structures in Open Source Software. Scientific Reports 9(1): 1-11

[viii] Bastolla, U. et al. (2009) The architecture of mutualistic networks minimizes competition and increases biodiversity. Nature 458: 1018-1020

[ix] Bacompte, J. & Jordano, P. (2007) Plant-Animal Mutualistic Networks: The Architecture of Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 38: 567–93

[x] Evans, D. M., Pocock, M. O. J. & Memmott, J. (2013) The robustness of a network of ecological networks to habitat loss. Ecology Letters 16(7): 844-852

Originally published at Systems Change Alliance

Top Photo by veeterzy

Carolina Carvalho is a network ecologist from Portugal who researches the interconnectedness of living beings and how we might apply this knowledge to help the human species live harmoniously within the web of life.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

Funding Successful Collaborations

Professor Wei-Skillern’s decade of research on successful nonprofit collaborations highlights key success factors that closely align with the behavioral changes required for collective impact initiatives to succeed.

In studying successful nonprofit networks, I have found that there are four key operating principles that are critical to collaboration success. These soft skills are the ‘secret sauce’ that differentiates mediocre collaborations from those that achieve transformational change. Surprisingly, the operating principles of funders who have successfully supported networks differ dramatically from common practice in the philanthropic sector.

- Mission not Organization – The Energy Foundation was founded in 1991 as a collaboration among Rockefeller, Pew and McArthur Foundations. With a $100 million commitment over 10 years, the founding donors provided patient capital, agreed that EF should be governed by an expert board rather than large donors, and encouraged the founding executives to be entrepreneurial and let the work of the foundation speak for itself (and to other potential donors) rather than get caught up in building the organization’s infrastructure. Their foresight enabled EF to catalyze the growth of energy philanthropy such that billions are now being committed to the field worldwide, though EF’s own budget has remained relatively modest, amounting to $100 million annually. EF’s goal has always been leveraged impact, not organizational scale. [ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Trust not Control - EF makes grants to regional groups that carry out energy policy work, then helps them coordinate so they can learn and adapt. Sometimes, EF grants to coalitions of nonprofits which are then able to regrant the funding according to how the local nonprofit leaders think the resources can best be utilized across the coalition. EF president, Eric Heitz describes the foundation’s operating philosophy as ‘service to the field.’ He notes, “We believe that people who are closer to the challenges are often in a better position to make the strategic call.” This is the ultimate in unrestricted funding--allowing the grantee full flexibility to use the funds not only internally, but also through its peers.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Humility not Brand - The Energy Foundation actively seeks to give credit to grantees, instead of trying to take the credit for itself. Indeed, I commonly refer to EF as the biggest foundation you’ve never heard of. It has been tremendously skilled at building the broader field of energy philanthropy yet it is little known. Its track record of success was instrumental in attracting multibillion dollar commitments to catalyze a network of similar foundations globally (see www.ClimateWorks.org). To get work done effectively through a network, participants need to build a reputation for making others look good rather than building a brand for its own sake.[ap_spacing spacing_height="10px"]

- Node not Hub - Although EF has no endowment and must fundraise annually for its own operations, it routinely suggests that donors give directly to others in the field if it is not able to add value. Furthermore, EF routinely invests resources toward field building without an expectation of a direct benefit. For example, EF has lent its executive staff for months at a time to peer organizations to develop capacity for working through networks among their counterparts globally. Eric Heitz will often give presentations to educate other donors to give to the energy field, even if funding for EF is not forthcoming. The goal should be to grow the ‘market’ rather than to to be the market leader.

While there are untold numbers of funders who promote collaboration among their grantees, the number of donors who live and breathe these principles in practice and as expectations among their grantees is rather small. If funders really expect to see more collaborative behavior in the field, a good place to start might be with themselves.

originally published at FSG.org

Four Network Principles For Collaboration Success

How are some collaborations able to achieve spectacular results while others fail spectacularly? This article introduces four key operating principles that build a culture for collaboration success.

About Jane Wei-Skillern: Jane Wei-Skillern is an associate adjunct faculty member at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business and a Lecturer at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business where she teaches social entrepreneurship and studies leadership and management of social enterprises. She has examined the topics of nonprofit growth and management of multi-site nonprofits, and for nearly a decade, has been focused on nonprofit networks. Her research on nonprofit networks examines how nonprofit leaders that focus less on building their own institutions and instead invest to build strategic networks beyond their organizational boundaries, can achieve dramatic gains in mission impact with the same or fewer resources.

PLEASE DONATE to help Network Weaver continue in it’s mission to offer free support and resources to networks worldwide.

“Lean Weaving”: Creating Networks for a Future of Resilience and Regeneration

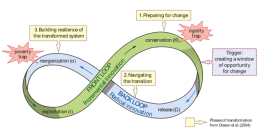

I’m fInishing up David Fleming’s book Surviving the Future, and buzzing with ideas and questions about the role of networks, network weaving and energy network science in these times of “systemic release” (see the adaptive cycle below, and more about the cycle here).

Fleming’s book, a curated collection of essays from the heftier Lean Logic, offers some compelling thinking about the trajectory of globalized and national economies – at best de-coupling, de-growth, and regeneration, and at worst catastrophic collapse – and the ways in which intentional and more localized culture building and reclamation as well as capacity conservation, development and management, might steer communities to healthier and more whole places post-market economy.

One of my favorite quotes from Fleming is that large-scale problems do not require large scale solutions; they require small-scale solutions within a large scale framework. That resonated immediately, even if I didn’t know exactly what he meant when I first read it. Re-reading more carefully, I hear Fleming making the argument that to take on systemic breakdown at scale is a fool’s errand – too massive, too slow, too much rigidity to deal with, too much potential conflict, too abstracted from real places and people.

Instead what is required is more nimble small-scale solutions happening iteratively and quickly (relative to how slow things move at larger levels). This suggests that action for resilience must happen at more local and regional levels, connecting diverse players in place, helping to encourage more robust exchanges of all kinds (including multiple “currencies”) and culture building. David Fleming offers the following definition of the lean economy (as opposed to the taut perpetual growth economy): “an economy held together by richly-developed social capital and culture, and organized around the rediscovery of community.” How might we weave that fabric even as others unravel?

Lean (network) weaving (a new term?) would focus on helping to create more intricate, high quality/high trust and diverse connections as well as facilitating robust, nourishing flows in tighter and more grounded cycles and systems. Part of the lean weaving would entail ensuring that smaller systems remain alert, quick and flexible so as to experiment, learn and adapt. And it would also maintain connection and communication between these smaller systems/clusters (Fleming’s “larger framework”), to facilitate learning and feedback of various kinds between them (not unlike proposed bioregional learning centers).

“The more flexible the sub-systems, the longer the expected life of the system as a whole.”

David Fleming

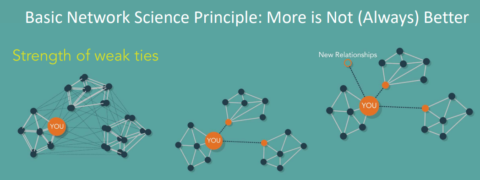

This idea of “lean weaving” also brings to mind the wisdom of network science as taught by Danielle Varda and colleagues at Visible Networks Lab. They make the point that when it comes to creating strong (resilient and regenerative) networks, more can be less in terms of the connections we have. Connectivity, like so much else in our mainstream economy and culture, can be ruled by a relentless growth imperative that is not strategic or sustainable and can cheat us of quality in favor of quantity.

More connections require more energy to manage, meaning there may ultimately be fewer substantive ties if we are spread too thin. Instead, the invitation is to think about how we mindfully maintain a certain number of manageable and enriching strong and weak ties, and think in terms of “structural holes.” For more on this network science view, visit this VNL blog post “We want to let you in on a network science secret – better networking is less networking.”

The COVID19 pandemic along with other mounting challenges may already be presenting the mandate and opportunity to get more keen and lean in our network thinking and weaving, not simply in the spirit of austerity and regression, but to cut an evolutionary path of resilience and regeneration (renewal). Network weavers of all kinds, what are you seeing and doing in this respect?

Originally published at Interaction Institute for Social Change

Curtis Ogden is a Senior Associate at the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC). Much of his work entails consulting with multi-stakeholder networks to strengthen and transform food, education, public health, and economic systems at local, state, regional, and national levels. He has worked with networks to launch and evolve through various stages of development.

This is How #WeGovern

Last year, we witnessed the near collapse of our collective systems—the systems that should be sustaining us when we need them most.

And the truth is, they’ve been failing us for generations. Today, amid a global pandemic, sustained violence against Black lives, brazen attacks by white supremacists, climate catastrophe, and pervasive economic injustice--we can see what Black and Indigenous folx have been saying for generations: these systems were not designed for us.

It is time they were.

We Govern is a roadmap for that creation. This foundational set of agreements were written by a group of predominantly Black, Indigenous, people of color across the US, to guide how we make the decisions that impact all of us--including how we choose to live together, use our resources, and build systems rooted in radical care.

It is an invitation to redefine governance.

Governance is the process by which we determine the norms and rules that guide everyday life and behavior, and we—all of us—have a role in it. Whether it’s through our personal lives as parents, friends, neighbors, caregivers, and stewards; or in our work as leaders and decision-makers—the choices we make each day determine our emergent future.

As our FAQ page says, “Whether deciding if it is worth it to struggle with a kiddo to eat broccoli, facilitating a healing conversation among friends, or creating a spending plan for clean energy in your town, the act of making choices for our collective wellbeing is governance.”

Governance is about making decisions together—at small and large scales—about the things that matter to us and impact our lives.

Today, together, we envision a more just, harmonious, and thriving future that refuses to leave anyone behind. We envision a world where we tend to ourselves and each other knowing that the choices we make each day add up to the world we’re building. We imagine systems of radical care in keeping with our sacred responsibility to care for future generations and the earth we share. The world we want is rooted in mutual care, deep relationship, dignity, and safety — for ourselves, for each other, and for the natural world.

Now, in the early part of 2021, we find ourselves still deep in a pandemic, clambering to stabilize the harms of last year, as we continue moving toward a still uncertain future. In this moment, a vision of another world is more urgent — and more possible — than ever.

By planting the seeds of commitment to collective care, we can create the world we want through the choices we make. WeGovern is an invitation to align our actions with our values—to commit to the foundational agreements we need in order to carve a path toward what’s possible.

The world we want — a world where all beings can thrive — begins with each of us. And it can start now.

To be counted among those who are embracing the sacred responsibility to take action and care for our collective wellbeing, sign on here.

Access the WeGovern Media Toolkit HERE or visit WE-Govern.org directly.

Resonance Network is a national network of people building a world beyond violence.

Appreciate Network Weaver's library of free offerings and resources? DONATE HERE to assist us in continuing the shared vision & collaborative campaign for equity, justice, & transformation.

Can problem-solving itself be problematic?

Intelligence is usually defined in terms of capacities like the ability to learn, to plan, to recognize patterns and to solve problems. So it has been hard for me – as an advocate of collective intelligence – to come to terms with the profound short-comings of problem-solving.

Problem-solving is universally respected and applied: If there’s a situation we don’t like, we believe it needs to be approached as a problem and solved. If the responsible person fails to solve it well, that’s their fault, not the fault of the problem-solving approach, itself.

In this essay I invite you to consider that problem-solving – as a way of handling troubling situations – has more pitfalls than most of us realize. In an ironic nutshell, there are some problems with problem-solving.

I find the very idea shocking. Problem-solving is so embedded in our thinking and language that it is hard to conceive of addressing challenges without trying to solve them as a problem. The problem-solving worldview is ubiquitous in our culture. I now think that that worldview generates a growing shadow for our civilization – a civilization profoundly dependent on the very problem-solving impulse that is making it increasingly vulnerable!

I’ve been considering how many of today’s “issues” and “crises” are rooted in earlier solutions. Consider, for example, what solution-based Progress looks like when we take account of its downsides:

- Better housing insulates us from “the elements”, thereby serving to alienate us from nature, dulling our instincts and capacity to respond with appropriate insight and urgency to environmental degradations unfolding around us. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Advanced medical care and provision of calories “solve” hunger and disease while expanding humanity’s environmental impact and frequently undermining deeper dimensions of individual, communal and environmental health. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Getting efficiently from A to B and acquiring our favorite products has disrupted Earth’s climate, depleted its resources, and generated massive amounts of garbage and toxicity. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Institutions to support people in need have generated systemic dependency and undermined traditional modes of mutual and communal caring and nurturance. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- The efficiency of money, mass production, mass commodification and mass mobility tend to replace relational interdependence, uniqueness, meaning, reciprocity, community and artisanship. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Communication technologies have transplanted us from communities of place to virtual networks of like-minded people far away, decreasing local social capital needed for physical communal resilience.

People are busily working on solutions to all the solution-generated problems noted above, while the whole interconnected body of life and its support systems are coming apart. I’m not saying we shouldn’t do things “to improve people’s lives”. I’m saying it seems wise to take better account of the downsides of our current approaches because, as novelist Phillip K. Dick notes, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” What we don’t take into account usually comes back to haunt us, sooner or later.

PROBLEMS WITH LINEARITY

Most of the shortcomings of our problem-solving worldview are grounded in the fact that it is fundamentally linear and the world is fundamentally non-linear. More often than not, the bigger the situation being addressed, the more nonlinear it is and the harder it is to understand, predict and control it. We can add to that challenge the fact that our “successful” problem-solving at smaller scales (like a decision to travel by jet instead of train) is generating ever-vaster problems at larger scales, thanks to how many of us are led to prefer problematic options.

This is one example of how our problem-solving efforts take us on an A-to-B fantasy trip from identifying the problem to finding a solution that makes the problem disappear. We believe in this simple story, even when evidence suggests it is incomplete and misleading. When things go wrong, we think that we (or someone) didn’t solve the problem correctly. We don’t think that there might be some issues with problem-solving, itself. After all, we see it working so well for small, simple, mechanical (non-living) challenges like fixing a flat tire – and even for complicated challenges like sending someone to the moon. (See my writeup of the Cynefin framework.)

Unfortunately, the linearity of problem-solving becomes troublesome when it is applied to large, complex, nonlinear situations and systems. These are the most common types of situation faced by organizations, communities and societies today. They are extremely messy even to try solving and, more often than not, when we implement such a solution we generate “side effects” which often become problems that demand solutions of their own, ad infinitum, as suggested by the bullet list above.

Problem-solvers even have a name for the most problematic problems. They’re called “wicked problems” because they are virtually unsolvable. The more alive and complex a situation or system is, the more it features interactive moving parts, vast influential contexts, autonomous agents, and evolving demands on the solvers, themselves, to dance and transform in ways that make any “solution” temporary, at best. All this interrelational movement thwarts our efforts to nail down The Problem and arrive at a final Solution that actually makes the problem go away.

The effort to apply problem-solving approaches to messy, wicked problems tends to not only fail to work as expected, but to generate hubris and tunnel vision in us as problem-solvers. We become captivated by the heroic narrative of generating clear solutions and thus reluctant to acknowledge how such complex systemic problems tend to have many tangled causes and how our solutions almost always generate new problems. We are inclined to underappreciate, downplay, or fatally ignore the evolving web of factors that make a satisfying solution so elusive. We hang on to our linear sense of problem-solving success.

IS PROBLEM-SOLVING ACTUALLY APPROPRIATE IN THIS CASE?

If we want to use problem-solving approaches wisely, we need to recognize where they may not be appropriate, and to deeply understand why that is. It also helps to know what approaches to use instead.

I offer below a list of some characteristics of situations, conditions and systems that do not respond well to problem-solving. None of them are cognitive deal-breakers or impediments to productive engagement; there are alternative approaches that can help us work with them. For each characteristic, I’ve included examples of approaches that would probably work better than traditional problem-solving. As with so many of my lists, this one is not to be taken as comprehensive, but rather as a doorway into thinking differently about this remarkably nuanced topic.

- If we encounter significant novelty and surprises in the problem domain, we’ll need to use less problem-solving and more openness, curiosity, exploration, and creative prototyping. As we learn more, we MAY be able to shift into problem-solving mode, but always very judiciously. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Where the problem domain is embedded in contexts – social or natural systems, histories, assumptions, etc., that seem to be in the background but actually shape or are impacted by the problem domain – we can investigate those larger contexts and convene generative conversations among players in them before attempting problem-solving. Often, deeper understanding of the situation and relations among the players will shift the context in ways that cause the original problem to shrink or dissolve entirely. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Where the problem is linked to other problems – e.g., at different scales, places, times, nodes of systemic causality, etc. – we’d be wise (as above) to undertake investigations and conversations about – and among players in – those related problem domains before even thinking of solving the original problem. Unacknowledged and ignored interconnections between problem domains is a major reason why solutions in one domain create problems in other domains. Of course, the more connections we acknowledge, the more complex we realize “the problem domain” actually is, challenging us to use even less linear approaches. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Where we find true complexity – in other words, constant interactivity, change, evolution, and emergence happening among elements within the situation – our responses require openness, diversity, fluidity, resilience, “dancing” with change and “surfing” the waves and rapids of change rather than problem-solving. Literally “solving” something in such a situation is futile because any “target“ for our efforts is always moving and morphing, often in response to whatever we do (and even who we are). Ideally, our level of responsiveness would reflect the level of mutual responsiveness unfolding among the other elements in the system. Improvisational dance might be the best metaphor for a workable approach. We would not see ourselves as separate, fight against the interactive energies, or push a prefigured plan. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- In response to significant but intrinsic uncertainties, it is most appropriate to respond with humility, intuition, appreciation, and exploring multiple perspectives in search of recognizable patterns rather than just trying to deny or solve the uncertainties so we can be certain enough to start problem-solving again. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- If we’re confronted by a polarity whose elements are deeply interdependent parts of a dynamic whole – such as freedom/equality, short term/long term, individual/group, etc. – their tension cannot be “solved” in the usual sense. They need to be managed for greater synergy, short-term situational prioritization (where one or the other side of the polarity is temporarily prioritized), and a long-term balance that is dynamic, not static. [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Predicaments – conditions that simply cannot be solved – challenge us to accept what’s going on, to minimize what harms may be associated with those conditions, to change ourselves as needed[*], and to support each other and the healthy functioning of whatever system the predicament is embedded in. In this, we may find the Serenity Prayer helpful: “God grant me the courage to change what I can change, the serenity to accept what I can’t, and the wisdom to know the difference.” [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Finally, Mystery is always present, inviting us to learn or deepen into the implicit awe-inspiring qualities of life and existence. Such learning and deepening can go on forever. Problem-solving is often a way to skip over that dimension of our experience – but we can always shift into Mystery at any time, simply for its own sake (setting aside the whole problem-solving impulse), or to gain perspective (since certain habits or assumptions can limit our view of what’s important or possible), or to make space for more creativity to help our problem-solving become richer and wiser. This may open the door to some of the less linear approaches listed below….

ALTERNATIVE PROCESSES

Some consultants note that the effort to solve problems can lower a group’s energy – despite the fact that some analytically inclined members of the group may enjoy that mode of thinking. Various exercises – creative, physically active, etc. – can be used make group problem-solving more enjoyable.

But that can make an unhelpful activity bearable. Luckily, there are totally different approaches to deal with undesirable conditions – other than problem-solving. These include the following, which I again offer with all my earlier caveats regarding lists! [Any processes not linked herein can be found here.]

- Active or strategic appreciation. This linked essay lists some process resources for this approach as well as this challenge to our imaginations: “What would happen if we deeply understood what was going on, if we saw and were truly grateful for the positive aspects of it and, in addition, if we used that recognition to help those positive aspects and possibilities become more present and alive in the situations we were addressing?…. [Rather than] pushing what we want to change towards a predetermined outcome… [What if] we’re evoking responses from the aliveness that’s already present or trying to help that aliveness show up more fully among us. As an approach to purposeful action, it’s more aligned to the nonlinear nature of chaos and complexity than traditional problem-solving approaches.” [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Conversation that evokes emergent shared understandings of what’s going on and what makes sense – e.g. Dynamic Facilitation and Convergent Facilitation [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Breakout-based gatherings where multiple perspectives on and dimensions of the situation can be explored with like-minded others – e.g., Open Space Technology, Warm Data Labs, and Ephemeral Group Process [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Creating contexts and awareness of relationship, resonance, reciprocity, and co-creativity not just with each other, but with all the elements of the situation or reality involved – e.g., Nonviolent Communication and Braiding Sweetgrass [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]

- Using the challenges of the situation for psychospiritual development, individually or collectively[*] – e.g., Mindfulness meditation and Bohm Dialogue [ap_spacing spacing_height="5px"]