MEASURING LOVE in the JOURNEY for JUSTICE

Below is the preface to this week's featured resource: Measuring Love in the Journey for Justice. Find the link to download this Brown paper at the end of this post.

MEASURING LOVE

Preface: A Sovereign Perspective

As this is a Brown—not white—Paper, we want to give some perspectives before you dig in. In a sovereign, self-determining perspective, we see Two Spirit people as sacred gifts. Children are treasured. Elders are respected and privileged. Womyn are beloved and respected and have power and voice. Fathers, sons, and boys are lifted up as the warriors, believers, and loyal friends that they are. Mothers, daughters, and girls are as valued as life itself, seen and treated as blessings. And all relations are sacred.

To be sovereign and free, our people need policies made of love, forgiveness, and connections.

As oppressed, exploited people of color in this work of social and racial justice, we have seen — and are seeing—children separated from their caregivers, caged in concentration camps. We are living in another era of the systemic denial of democratic civil rights. To be sovereign and free, our people need policies made of love, forgiveness, and connections. Our communities deserve health and educational equity; land and housing justice; economic independence; living wages (as in universal minimum income). Our people want restorative justice practices to replace punishment and lockup. Our communities want community organizing and advocacy, block by block. Our people need community controlled governance and accountability systems. We want civic leadership everywhere, as the right to vote goes with the rights to drive, assemble, drink, and travel.

This Brown Paper flips the script of what is acceptable as a “Paper” on its head. It is not a “formal,” research-based, finished product of the traditional type. It comes from the heart and is meant to be used—like love. It is meant to spark dialogue and provoke.

In it, we are asking ourselves, “Are we loving bravely enough?”

And “How much am I loving?” “What else I can do to be in community from a place of love?” and “How am I wielding power fused with love?”

These are the essential questions posed in our brown paper. We are excited to bring this out into the world to provoke, connect, and build with you.

We have so much to love. We love YOU because we know if you’re reading this paper, you know what it’s like to be powerless and not feel loved—and are working on bringing about more justice in the world.

We release our intentions into the universe. We want to know what your reactions are. We thank you for honoring us by your comments and discussion.

Spread your love. And, we know we are rising as one.

Download Measuring Love in the Journey for Justice HERE

Shiree Teng has worked in the social sector for 40+ years as a social and racial justice champion – as a front line organizer, network facilitator, capacity builder, grantmaker, and evaluator and learning partner. Shiree brings to her work a lifelong commitment to social change and a belief in the potential of groups of people coming together to create powerful solutions to entrenched social issues.

*After the Measuring Love Brown paper was released, Shiree's co-author was arrested on allegations of child molestation. She addresses this in a "Letter to Beloveds" - an excerpt from her next collaborative paper, Healing Love into Balance. (which will be highlighted at NW in the coming weeks.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

We need to talk about leadership

Visionary collective leadership to build a world where everyone belongs

What is the quality of leadership we need to build a world where everyone belongs?

I’m specifically interested in that ineffable quality of visionary collective leadership: the rare capacity to inspire and transform a collective to whom you are not in direct relationship. I think here of social movements, especially those which transcend borders: the universal emerging from the particular (Occupy, the Arab Spring, #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, etc.).

It feels so important to me that we get this “right.” While there has been talk of a leadership crisis for decades, I’m particularly concerned with the contemporary manifestation that is undermining our movements for justice. In Moe Mitchell’s ground-breaking diagnosis last year he cited “anti-leadership attitudes” as a core impediment to the transformation we seek. We desperately need bold leaders capable of caring for the whole… what does that quality of leadership look like? How can we cultivate it?

Here’s where I’m coming out (TL;DR): Visionary leadership is the capacity to take responsibility for using power to care for the whole. It is the relational capacity to offer an embodied invitation and a unifying narrative, in accountability to the whole.

To exercise leadership is to offer a gift: a gift that seeks to unlock and channel the gifts of others. To offer that gift is to assume responsibility for the whole, and therefore to accept accountability to the whole.

“Leadership is connecting what was separated”

I love this definition from Marcella Bremer, channeling Otto Scharmer. This feels like a great starting point for leadership that builds belonging, which in my understanding is about restoring connection and returning to wholeness. This provides the prism through which I want to explore leadership today, and the central metaphor through which I understand this work: it’s about building bridges.

In sifting through the literature on leadership for a definition that resonates with how I understand it, I came across this from Kevin Kruse:

Leadership is a process of social influence, which maximizes the efforts of others, towards the achievement of a goal.

I think this definition offers a solid foundation for our inquiry, and it’s worth unpacking; I’m including here some parenthetical notes about how this definition lands with me and the direction I want to take it:

- leadership is a process (not just what but how)

- of influence (it’s about power)

- it is relational (in service of a collective)

- it is about inspiring others to do their best (unlocking gifts)

- and it is in service of an outcome (pointing the way forward)

I will unpack each of these components in turn before offering four additional aspects that feel important to how I understand this quality of visionary leadership:

- not leading followers, but inviting co-creators

- leading as an embodied invitation

- offering a collective narrative

- in accountability to the whole

Admittedly, a definition of visionary leadership that includes nine components may be a little bold: too many ornaments on the tree, I fear. The point in enumerating them, for me, is to illuminate different domains of practice. I aspire to be the kind of leader who builds belonging, but I have so few models of what that looks like in practice that I often feel like I’m floundering in the dark. This is an effort to provide some light.

Visionary leadership is about process… and product

I struggled with this point for awhile, before finally arriving at this distinction: there is process leadership, and there is outcome leadership. They are different qualities, and each important in their own right; but the quality of visionary leadership I’m talking about requires both. [To be clear: there are many other types of leadership, all of which are vitally important; Alanna Irving offers a helpful overview here. For the purposes of today’s post, I’m focusing specifically on visionary leadership, as distinct from these other forms.]

Process leadership is goal agnostic; the goal is the process. This is facilitation, or mediation; Patricia Wilson defines it as a core attribute of the practice of Deep Democracy:

Process leaders create the container for building trust and shared understanding amid diversity and difference.

This work is necessary, but insufficient: we also need goal-oriented leadership. As Ericka Stallings recently put it:

Leadership is taking responsibility for getting things done.

This outcome focused definition to me is more akin to what I think of as management, or implementation. Also vitally important… but incomplete. Visionary leadership, as I understand it, must include both.

And: the means and ends must align. How we get to our goal is essential to getting there: we can’t strike the rock and hope to make it to the promised land.

Leadership is the right use of power

All definitions of leadership speak to influence: the ability to get people to do something. To me this is about wielding power. Cedar Barstow, who wrote a book on the “right use of power,” defines it like this:

Any use of power that does any or all of the following: prevents harm, reduces harm, repairs harm… to evolve relationships and promote sustainable well-being for all.

So that’s our baseline (power to a pro-social end, as distinct from power as domination). But the right use of power in visionary leadership I think requires four other components:

- It is about using your power as a leader to increase the total amount of power available. Power is not zero-sum: a core function of leadership is to generate new power, to unlock latent discretionary energy in individuals and the system. (I love Eric Liu’s work on the idea of power as abundant). This is the core work of organizing.

- It is about addressing how systems of oppression impact the existing power available to people. Oppressive systems harm both marginalized people by denying their intrinsic power, and dominant groups by granting them a toxic form of “power-over.” This is the core practice of what Change Elemental calls “deep equity”: working with privileged people to relinquish power-over, and supporting marginalized people to step into their personal power. Hahrie Han put it beautifully:

At the core of organizing is not just getting people to take action but instead it’s engaging people in a transformative process through which they develop their own leadership and their own capacity to make change.

- It is about channeling this unlocked power. Power is potential: nothing changes until that power is applied in service of something. This is where vision comes in, and direction (discussed below).

- It is about relinquishing your power. Ah, here’s the paradox: there comes a point where for the leader to continue to hold onto power can be a drag on the total power available in the system. Because once others have accessed their own power, they now need to influence the direction: they are no longer “followers” but co-creators… and the original “leader” needs to shift into a new role (not letting go of leadership, for which I think there is always a need, but for letting go of power as initially practiced). More on this below. I’ve been sitting with this line from Laszlo Bock, commenting on what it means to lead in the 21st century:

What’s critical to be an effective leader in this environment is you have to be willing to relinquish power.

Leadership is relational and collective

This is an obvious but under-emphasized point: to lead is to be in relationship to whomever you are purporting to lead. As the West Wing famously noted (I’m sad this video clip isn’t on YouTube, and HBO won’t let me upload it):

You know what you call a leader with no followers? Just a guy going for a walk.

Celine Schillinger goes so far as to describe leadership as a “collective capacity.” I take her point: all leadership is relational and shaped by the context we find ourselves in. And: the quality of leadership I’m focused on here is an individual capacity enacted in a collective context.

There are two extremes I’m reacting to here: one is the Western aggrandizement of the individual leader, the cult of personality that is the opposite of what I think is needed (see Musk, Elon). This approach to leadership centers the “I” of the leader (often in dangerously egocentric form), and the expression of that “I” through the organization they’ve founded… and either ignores or deprioritizes the needs of other people in the organization/world. But the other extreme is the often-lauded concept of servant leadership; the oppositional response the the apotheosis of the “I.” Where traditional American dominant culture leadership centers the “I,” servant leadership centers others, or the collective. Robert Greenleaf, who coined the term, explains:

The servant-leader puts the needs of others first.

The quality of relational leadership I’m seeking declines to accept this false binary. I don’t think we can be effective leaders if we aren’t in touch with our own needs and desires. Both because we will burn out (self-sacrifice is not sustainable), and because we are depriving the collective of our vision: we forget that “I” is part of “We.” Paradoxically, to not speak for our needs (servant leadership) is to undermine the collective. And of course we can’t be effective leaders if we are only in touch with our needs, without caring for others or the whole: that isn’t leadership, that’s narcissism.

I aspire to a form of leadership that is interdependent. It’s no surprise that our colonial language has words for selfish and selfless… but not self-full: the very idea of interdependence under systems of oppression is in a literal sense inconceivable. The quality of leadership I long for instead seeks to simultaneously meet the needs of everyone: what in Building Belonging we call I, We, World. In this understanding we don’t put anyone’s needs “first”; rather, we hold them all as equally important and not opposed. As nonviolent communication reminds us: needs are universal, and never in conflict.

Leadership is about unlocking gifts

This to me has always been the core of how I understand leadership. It’s related but different to the point around power: it’s not just supporting others into tapping into their power…. it’s about helping people identify and share their gifts. This to me is the subtle but important difference between “servant leadership” (which subjugates the self) and leadership that is of service: grounded in the I, connected to the We and the World. Rachel Naomi Remen has my favorite treatment of this distinction, explaining:

We can only serve that to which we are profoundly connected… Serving makes us aware of our wholeness and its power. The wholeness in us serves the wholeness in others and the wholeness in life.

The key point here: we actually can’t be of authentic service (we can’t lead) if we aren’t deeply connected to ourselves… grounded in the “I.” Dominic Barter’s exquisite meditation on empathy really captures this idea for me (thanks to Miki Kashtan for introducing me to his work). The whole thing is worth a watch: so much wisdom and insight packed into a few short minutes. The definition of empathy I want to highlight here:

Lending my sense of them back to them... that helps them connect to themselves in a deeper way… That inner connection is within myself, and that inner connection allows me to engage with someone else without me being submissive to them or attempting to dominate them.

I would echo Dominic and go further: we need others to help us identify and share our gifts. I don’t think—especially as we are socialized into cultures of domination—that we can fully grasp our own gifts without them being refracted back to us through someone else’s lens. Indeed, it is this act of what Dominic calls empathy and Rachel calls service that I consider the foundational act of leadership. It is to offer the first gift: to give others the radical gift of being seen and celebrated. I love Robin Wall Kimmerer’s writing on the power of gift:

Leaders are the first to offer their gifts... leadership is rooted not in power and authority, but in service and wisdom… This is our work, to discover what we can give. Isn't this the purpose of education, to learn the nature of your own gifts and how to use them for good in the world?

Yes. Building on my last post: it is to make others feel like they belong. It is that felt sense of belonging (which includes safety) that allows people to unfurl, to blossom, to acknowledge to themselves and share with others their gifts. Thinking about this post I was pleased last week when picking up my kids from elementary school to see this poster in the cafeteria:

Yes. And it is a fundamental task of leadership to help people identify their unique gift and contribution.

Leadership points the direction…

Unlocking gifts is necessary but insufficient. To unlock gifts is the work of an educator. A leader goes a step farther, and channels those gifts in service of the whole. It is this aspect that distinguishes visionary leadership from process or facilitative leadership.

But: to lead in a direction is not to direct; there is a quality in visionary leadership that is distinct from the “goal leadership” of traditional management structures. I like this nuance from Simon Sinek:

I also like the implication here: it’s not about a destination (a defined outcome), it’s about a direction. There is something important about the ability to chart a course through complexity, to navigate uncertainty… a quality that some have called “emergent leadership.” This is the “visionary” part of visionary leadership: it is seeing a path that others do not yet see. In my last post focused on visionary leadership, I talked about visionary leaders as “human signposts” (following Vincent Harding): illuminating the path forward without necessarily defining where it ultimately leads.

There’s something important here about humility: the kind of groundedness that comes from embodied presence and clarity of vision… paired with the recognition that of course the “leaders” doesn’t have all the answers. Adam Grant calls this “confident humility.”

…and invites others to shape the path (co-creators, not followers)

We’re now expanding the definition of leadership that we started with. I’ve unpacked and added nuance to the five elements Kevin Kruse named, and now want to introduce four other ideas to complete my inquiry into the qualities of visionary leadership that build belonging. The first concept I want to offer here is the invitation to co-creation: it is the piece I struggle with the most.

True visionary leaders recognize that leadership is not about seeking followers, but about inviting others to share and shape the vision… and the direction. The goal is to build a movement, not an empire (a line I first heard from john a. powell). Visionary leaders may point us in the right direction, but ultimately we must walk the path. We cannot stay in the follower role. As Gloria Anzaldúa reminds us: “we make the bridge by walking.”

This was the struggle I took up in my last post wrestling with visionary leadership: it’s that perennial tension between holding on (right use of power as leader to catalyze collective action: illuminating the path) and letting go (relinquishing that power to relax into co-holding and co-creating: joining others in walking that path, and together creating the bridge). Let go too soon, and no one sees the path, or feels emboldened to commence the journey into the unknown. Hold on too long, and people never develop the capacity to build the bridge and shape where it goes. And of course, the visionary leader cannot alone determine the destination; in this I differ from the Source work that Tom Nixon has been synthesizing, building on Peter Koenig (though I find it insightful!)

I recently came across a couple ideas that feel like they get at the quality I’m seeking here. I haven’t found a name for it, which is part of what makes it so hard to describe: it’s not quite co-visioning, but it’s something like that. adrienne maree brown recently explained:

There is a difference between inviting you to join my imagination, and sharing your own imagination to see where we might meet.

Yes. Richard Rohr expressed a similar sentiment in sharing his vision for the world, and for building transformative movements. I love this distinction between followers and fellow travelers:

Not people who love me, but people who love what I love.

I’ve had the experience a couple times now where the audacity of my vision is not only welcomed but reciprocated by fellow bridge-builders… and it’s nothing short of delightful. Where I can offer the fullest expression of my gifts, and experience the power of others offering theirs. This is Norma Wong’s invitation in action:

How do we stay in relationship with each other's gifts?

To do so well is an artform (work in progress for me!), and simultaneously incredibly difficult and incredibly liberating. This is what I think Miki Kashtan was getting at when she observed:

The deepest form of human wisdom is mutual influencing.

Visionary leaders tell a good story

The second thing I want to add to Kruse’s definition is the importance of telling a good story. Jay Van Bavel names this explicitly:

One of the most important roles of leaders is creating a narrative.

Yes: humans learn through story; we make sense of the world through narratives. Jacqui Lewis cites Howard Gardner’s foundational work, explaining:

Good leaders tell compelling stories that change the stories in the minds of followers.

Here Lewis conceives of storytelling as an act of transformation: it is the invitation into a new worldview, a new way of making sense of the world and our role in it.

I’ve come to believe that there are three components to an effective narrative, which guide my work in Building Belonging. First, it must aid with sensemaking: it must help the listener/audience understand the world as it is AND their role in it. Second, it must include an invitation to imagination: to temporarily cast off the shackles of the status quo to situate ourselves in a different and better future. It is to remind them (and ourselves!) of Paulo Coelho’s radical truth:

People are capable, at any time in their lives, of doing what they dream of.

Third, it must offer a path from here to there: a bridge from painful present to delightful future. Writing on my personal blog way back in 2012 in an extended reflection on moral leadership, I said this:

A successful leader builds a narrative both around what is wrong (problem definition) and a path to a solution.

To build a narrative is to build a world: it invites people into a different understanding of reality. And most importantly: it invites them into agency around creating that new world and reality. I like this line from former IBM CEO Ginni Rometty:

Building belief is about moving people to embrace an alternate reality for themselves and others, and then to willingly participate in creating it. It’s the first major step if you want people to change, because they have to understand and believe in the change. (emphasis in original)

Leadership embodies the invitation

The third thing I want to add to Kruse’s definition combines two ideas. The first is to conceive of leadership as an act of invitation: if we are serious about building a world without coercion, we must practice it from the beginning… by inviting people into choice. I love Richard Bartlett’s simple offering here:

Leadership is the capacity to make a compelling invitation.

This to me is the central capacity of generating new power in the system, of what I think of as positive-sum leadership. Alanna Irving, a collaborator with Richard in the Enspiral project that has birthed so many lessons on emergent leadership, explains:

Invitations to responsibility can create space for others to achieve.

Second, that invitation must be embodied. This is so often what separates good leaders from great leaders, and remains a source of deep aspiration for me personally. I understand the need intellectually to embody the invitation. But as always, my cognitive understanding is far faster than my body’s capacity to integrate and embody… sigh, work in progress. Reviewing Howard Gardner’s work, Warren Bennis notes that one of the four distinctive qualities of leadership is:

A relationship between the stories leaders tell and the traits they embody.

Right. Humans have a deep and visceral ability to attune to body language and detect incongruence. This is why we are so drawn to magnetic figures like Barack Obama, whose public narrative was so powerfully embodied in his own story and body. This is the art of embodied leadership, and thankfully we’re slowly waking up to how fundamental this is to the entire enterprise. Places like the Strozzi Institute or generative somatics, and new offerings like Prentis Hemphill’s Embodiment Institute are seeking to meet this emerging demand.

To exercise leadership is to be accountable

One final idea here before I close. This to me is the natural companion to the notion that leadership is collective: to act on behalf of the whole is to be accountable to that whole. So often in dominant culture renderings of leadership there is no accountability, or if there is it only flows from those on the bottom to those on the top: did you meet your deliverables, did you do the thing I asked (or told!) you to do. To me leadership properly understood is mutual and accountable: the leader invites from a place of noncoercion, and in accepting responsibility accepts accountability.

This is partly why leadership is terrifying for so many: in our punitive carceral culture, we don’t have practice with accountability inside of interdependence. I loved this whole interview with Nwamaka Agbo, but this line in particular continues to resonate:

We don't know what it means to lead, until we have to make difficult decisions and take accountability and responsibility for the consequences of those decisions.

Here’s how I see the flow: first, to have a gift is to have responsibility to offer that gift. As Robin Wall Kimmerer reminds us:

Duties and gifts are two sides of the same coin… A gift is also a responsibility.

Second, because all gifts properly understood are in service of the whole, to offer that gift is to take responsibility for the whole. Miki Kashtan sees this as the defining characteristic of leadership:

The willingness to take responsibility for and care for the whole in interdependent relationship with others.

Third, to take responsibility is to invite accountability: in serving the whole, we become accountable to the whole. Peter Block calls this the foundation of accountability, explaining:

Accountability is the willingness to care for the whole.

Laureen Golden helped inspired this reflection in me with a recent post, where she offers this definition:

Leadership is a quality of presence that enables us to be responsible and response-able; it's a capacity to connect with and be guided by the animating force of Life. (emphasis in original)

This is subtle stuff: we are accountable both to the We (the collective to whom we are offering our gift of leadership), and to the World… in service of life itself. Ideally these are integrated and the same thing… but of course we humans have our own traumas, shadows, projections. So we must learn to discern between the invitation to appropriate accountability (in touch with source, attentive to impact) and the faux accountability that we rightly critique in “cancel culture.”

Brian Stout is a systems convener, network weaver, and initiator of the Building Belonging collaborative. His background is in international conflict mediation, serving as a diplomat with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in Washington and overseas. He also worked in philanthropy with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, before leaving in early 2016 to organize in response to the global rise of authoritarianism and far-right nationalism. He recently returned to his hometown in rural southern Oregon, where he lives with his wife and two children.

originally published at building belonging

featured art by Paul Akiiki: We Belong Together

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

donate in the box above or click here

EXPLORING THE COLLABORATION CYCLE

Below is an excerpt from the full article which can be downloaded here or at the bottom of this post. This article a part of the Tamarack Institutes Collaborative Governance and Leadership series.

The Collaborative Context

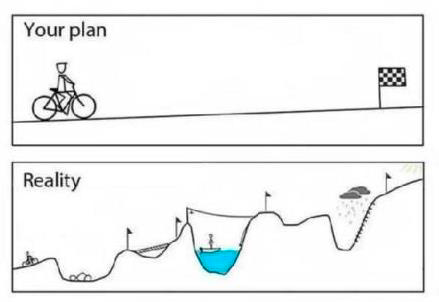

Many enter into collaboration thinking that the shared work is a linear and flat process from start to end. One of the favourite images describing collaboration that is often included in Tamarack power points is this image of plan versus reality. It captures the reality of collaboration including the twists and turns that collaborative efforts face as they move from start to completion. It can include obstructions like boulders and choppy waters and other challenges which are found obstructing the path along the way. This image always receives a small chuckle because individuals in the room have experienced these challenges.

However, the reality image still conveys a relatively linear, if upward, and challenging experience. This image is relevant for collaborative efforts seeking to achieve a result that is more defined such as the exchange of ideas, or development of a new program or service.

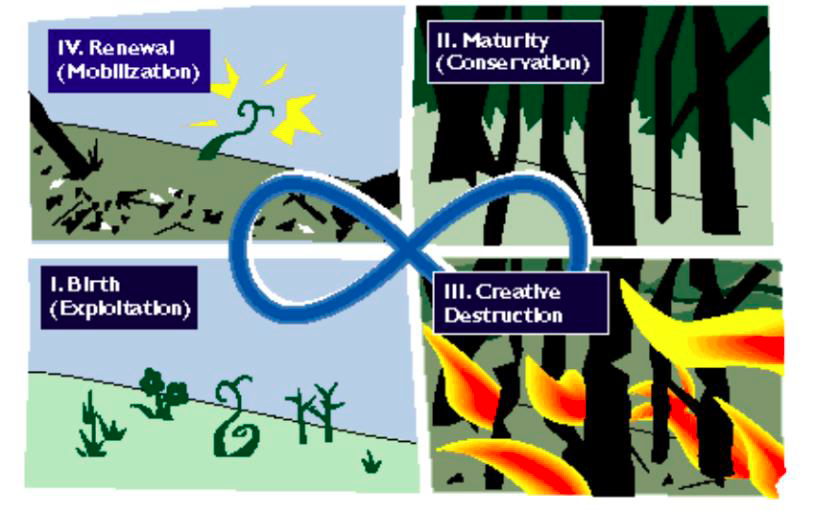

For more significant community change efforts, a different approach was introduced to Tamarack by Brenda Zimmerman of The Plexus Institute. Zimmerman described community change as a more cyclical process mirroring phases of development found in ecology.

The ecocycle concept is used in biology and depicted as an infinity loop. In this case, the S curve of the business school life cycle model is complemented by a reverse S curve. It is the reverse S curve, shown below with the dotted line, that represents the death and conception of living systems. In our depiction of the model, we call these stages creative destruction and renewal. The importance of the infinity loop is that it shows there is no beginning or end. The stages are all connected to each other. Hence renewal and destruction are part of an ongoing process.

Being an infinity cycle, there is no obvious start or end to the cycle. Let us begin our examination of the stages at the beginning of the traditional S curve. We will begin each phase by using the biological example of a forest and then look at the analogous phase in human organizations.(i)

The four phases of the ecocycle, as described by Zimmerman and the Plexus Institute follow the traditional (and linear) growth curve from birth to maturity. However, it also considers a renewal loop. The renewal loop includes a creative destruction phase and a renewal phase.

The image from the Plexus Institute website displays and describes the ecological cycle of a forest which starts with a variety of different plant growth (birth) which leads to increasing density as the forest grows to maturity. At maturity, the forest becomes increasingly vulnerable because of the density of growth. It can experience rot through invasive moths or pests or be ruined because of a forest fire. The creative destruction phase creates the space for renewal and regrowth. It is often the results of decay that enable the regrowth or renewal to seed.

Using the Ecocycle to Inform Our Practice

The ecocycle has been adapted by many organizations over the last several years to describe a better way of understanding community change and collaboration cycles. Tamarack has used the ecocycle to inform our practice of supporting communities tackling complex issues like ending poverty, building youth futures, deepening community, and navigating climate transitions. Tamarack, influenced in our early years by Brenda Zimmerman, recognizes that communities are dynamic and responsive. Even as collaborative tables begin to intervene in community change efforts, the community begins to respond, grow, and change. The ecocycle approach can be useful to collaborative tables to help understand and navigate dynamic change recognizing that change is not linear but rather exists in phases and cycles.

From Ecocycle to Collaboration Cycle

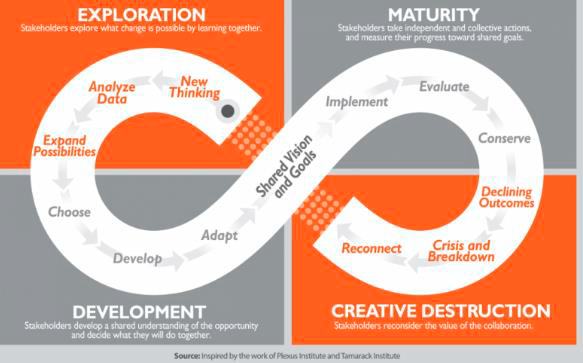

There have been many articles written about the Ecocycle and adaptations to this approach. One useful adaptation of the ecocycle was developed by Chris Thompson, Collaboration – A Handbook from the Fund for our Economic Future. (ii) In this handbook, Thompson adapts the ecocycle to a collaboration cycle approach. Thompson builds of the Plexus Institute ecocycle framework and Tamarack’s approach to adapting the ecocycle to community change efforts. Thompson uses the phases language of development, maturity, creative destruction, and exploration.

Thompson describes three elements which are vital to impactful collaboration: capacity, process, and leadership. The collaboration cycle is useful to focus on the process of collaboration.

This cycle serves as a roadmap for the diverse players who are along for the collaboration journey. It is invaluable to new participants joining an existing collaboration, as it can be used to help them understand where the partners are on the journey. Advocates of collaborations, particularly those performing the key collaboration functions, also should take the time to help each partner assess where they are on the cycle. Not every partner travels through the cycle at the same pace. (Thompson. Page 29) Thompson provides useful steps in each of the phases such as developing new thinking, analyzing data, and expanding possibilities in the exploration phase

In the development phase, the steps include choosing strategies, developing approaches, and adapting as the collaboration moves forward. The maturity phase includes implementation, evaluation and in some cases conserving to build on successful results. The creative destruction phase is initiated by declining outcomes, crisis, or breakdown and reconnecting.

Access the full article HERE

Liz Weaver is the Co-CEO of Tamarack Institute and leading the Tamarack Learning Centre. The Tamarack Learning Centre advances community change efforts by focusing on five strategic areas including collective impact, collaborative leadership, community engagement, community innovation and evaluating community impact. Liz is well-known for her thought leadership on collective impact and is the author of several popular and academic papers on the topic. She is a co-catalyst partner with the Collective Impact Forum.

Liz is passionate about the power and potential of communities getting to impact on complex issues. Prior to her current role at Tamarack, Liz led the Vibrant Communities Canada team assisting place-based collaborative tables to move their work from idea to impact.

featured image found here

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

The DNA of Organizational Transformation—Structure, Relationships & Shared Purpose

In my role as an organizational well-being officer at IBSS Corporation, I was given a unique opportunity. As part-scientist, part-community builder, and part-alchemist, I was able to bring my personal and felt understanding of well-being and investigate the work environment to see what was missing and create experiments to address the gaps. With great interest and enthusiasm, I explored all facets of employee well-being and built, reverse engineered and validated those conditions and components that were needed for well-being to thrive.

I was excited and curious to learn how an organization would look and function that put the well-being first of its employees, customers, suppliers, community, and even the earth.

- How would people feel going to work? How would that impact customer relationship and loyalty?

- What would that mean to suppliers who work with the organization and would they begin to absorb some of that well-being into how they operate?

- How would the organization be viewed by local and other communities? Would they consider the organization part of the community or just another name on a building they see as they walk by?

During my 3-year tenure, I investigated and experimented constantly. At the end of that window, I finally began to uncover the key fundamentals an organization needs to support the well-being of its employees. Then the pandemic hit. I don’t know if it was all the medical talk about vaccines and DNA or that I just had more alone time than usual to contemplate organizational well-being and transformation, but about six months later I had an aha moment! My insight involved genetics—specifically, the DNA of an organization.

“Double helix” is the biological term for the instantly recognizable structure of DNA. Often visualized as a twisted ladder or spiral staircase, the double helix consists of two strands of DNA wound around one another. Each of these strands holds different information that, when combined, form the language of the genetic code. I applied the double helix analogy to an organization’s structure, starting with the idea that these two DNA strands represent the building blocks for deep change and transformation.

- Structure: I call one strand the structure. This is the backbone of an organization, and it consists of all the operating procedures and workflows that are used to create internal change such as policies, processes, strategies, org charts, IT systems, etc. These are often used as levers to create change in an organization because they are typically measurable, tangible, and easy to see.

- Relationships The second strand, I call relationships This strand encompasses the individual work relationships employees have with the dozens of other employees they regularly interact with and the quality of those relationships.. Unlike structural elements, relationships aren’t something easily seen or measured, but it can be felt. It’s very similar to when a good facilitator can feel the group, or a performer can feel the crowd.

- The double helix’s twisted DNA strands are connected in the center by hydrogen bonding. This was the critical piece I soon realized was missing. The golden thread binding structure and relationships together is shared purpose. From an organizational standpoint, this third component may be the most important.

Aristotle famously said: “…the totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is something besides the parts…” When the raw materials of structure, relationships, and shared purpose bond together they transmute into something very different, something far greater. This new harmonious state or way of functioning is experienced as emergence or flow. To achieve effective organizational change, all three of these fundamental building blocks must be present and working together.

I call this powerful trio of structure, relationships, and shared purpose the DNA of Transformation. It provides the unique genetic code that each group or organization needs to become a place of well-being, connection, care, compassion, empathy, and love while fulfilling its purpose. In my experience, this model can affect change on all levels—with people, teams, organizations, and systems. When organizations change at a DNA level the transformation becomes so deep that going back to the old ways of operating is just not possible. It’s like a butterfly trying to get back into its cocoon to become a caterpillar again—it just doesn’t happen! Does your organization know the right keys to nurture successful change and unlock well-being?

Derick Carter is a heart-centered facilitator, trainer, coach, and leadership consultant who guides organizations, communities, and emerging leaders to create social and organizational change, enhance well-being, and build togetherness. Having worked as a well-being officer for an award-winning government contractor, Derick is passionate about empowering organizational transformation, health, and wellness through his DNA Change Model, which binds structure and relationships with shared purpose. Derick also works at the forefront of heart-centered leadership development and is committed to collaboration and growing organic action from collective wisdom. With over 25 years of experience, Derick’s broad client base includes Fortune 500 companies to mid-size and small businesses, government agencies, non-profits, social enterprises and communities, and public works organizations. Additionally, Derick is a certified Feldenkrais Awareness Through Movement instructor, Functional Integration practitioner, and Heart-Centered Meditation guide.

www.buildwithderick.com / email: derick@buildwithderick.com

featured image found here

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

Making “risky” business our business

Bridging the gap between funders and the needs of grassroots groups

In previous blogs we have talked about the need for grassroots movements vs. funder’s resistance to risk, and questioned the meaning of the word in this context. Next in our exploring risk in funding series, we wanted to look at the role that we, The Social Change Nest, play in all this. How do we make sure that we’re walking the walk as opposed to just talking the talk?

It is clear that there is a disconnect between how risk is perceived by funders and the reality of what it looks like for communities. The panellists from our Risky Business event have already said it better than I could, so I’ll pass the metaphorical mic over to them:

“Everyday people in communities are balancing bigger risks than you’ve ever considered” – Caroline Mawer, Camden Giving

“It’s absurd that funders are holding grassroots organisers to account when they are held to account by their own communities.” – Jo Wells, various social sector advisory roles

What came up when we surfaced this conversation was that there needs to be a change of mindset. Instead of asking ‘what is the risk of giving this money,’ funders need to be asking themselves, ‘what is the risk of not giving this money?’

As another of our panellists Nonhlanhla Makuyana (Decolonising Economics) said, “giving a little bit doesn’t create the sustainability needed to build strong movements that take us to the future we want to get to.” If we believe in funding grassroots groups, having seen the important role they play in social change, we need to be giving enough resources for them to not only survive, but thrive.

To get there, we need something to bridge the gap between where the funders are, and the needs of grassroots groups. This is where The Social Change Nest comes in. Our deep understanding of the two sides has allowed us to build frameworks and services to help navigate this disconnect. Acting as a kind of ‘social change scaffolding’, we aim to offer services that close the gap between funders and grassroots groups, whilst sharing the resources and advocating for longer-term systemic change.

In addition to holding spaces for discussion such as our Risky Business event, we are guiding funders through processes to enable a smooth transition to embracing risk. We also offer vital support to grassroots groups to enable them to build out the capacity needed so they are ready to thrive as they get the funding they so deserve.

social change is slow and takes time – well, less time if you fund the grassroots groups and movements at the forefront of social change

Supporting funders through this change process makes it an easier shift for them to fund grassroots organisations directly in the future – we are playing the long game here. After all, true social change is slow and takes time – well, less time if you fund the grassroots groups and movements at the forefront of social change…

Much like any kind of scaffolding, the end goal is for us to step away, take the temporary structure down, and find behind two well-connected metaphorical buildings – one representing the funders, and the other the communities they serve. In the meantime, we’ll be here talking to and guiding funders and empowering and strengthening community groups.

Grace Sodzi-Smith,

Partnerships Manager at The Social Change Nest

A solution enabling funders to fund movements, networks and changemakers

Don’t let bureaucracy become the oppressor. At the core of The Social Change Nest, is a desire to provide a solution which enables funders to be able to fund movements, networks and changemakers without adding to their problems.

All of the funders we work with see the value in community led change. They approach us wanting to find a way to send funding to grassroots groups that involves minimal administrative work for the groups and allows them to work with the funding in a way that suits them.

Funders come to us frustrated with their internal systems and we step in to lift this barrier

However, some of the funders we work with come to us in a position where their current way of distributing funds involves navigating a heavily bureaucratic system of getting funding signed off. The systems that a lot of funders work within limit the pace at which they can deliver funds to grassroots groups in the timelines that the groups need it. This then causes missed opportunities for grassroots groups to receive the funding at all which, you might say, defeats the point.

Funders come to us frustrated with their internal systems and we step in to lift this barrier. We do this in part, by providing the opportunity for groups to be fiscally hosted by us on the Open Collective platform, where they can see and manage their funding transparently and collaboratively.

Granting to grassroots groups inherently involves microgranting, which is more admin than managing bigger grants, and a lot of funders don’t (yet) have the infrastructure or the time to invest in building the systems to navigate it. We enable funders to distribute small grants at a quicker rate than big grants, which tend to happen once in a blue moon. This then means grassroots groups get to work continuously as opposed to waiting for ages to get started and so potentially losing out on taking on time-bound projects.

funding doesn’t have to involve a series of hierarchical hurdle jumps

Transparency, trust and communication is central to our process; we build relationships with both funders and groups so that everyone involved understands what our process is and can feel supported throughout. This helps to demystify the world of funding and receiving grants by both showing groups how they can manage their funding easily and transparently, and also showing funders that funding doesn’t have to involve a series of hierarchical hurdle jumps. Funding then emerges as something much more doable and in their control than both sides had originally thought.

In evaluating our impact, we found that 80% of funders* said working with The Social Change Nest has encouraged them to make deeper shifts to their funding policies or models. Lankelly Chase are one of these and have changed their policies through their board. Joe Doran reflected on this by stating “It’s been heartening, and heartbreakingly obvious, to see how changing the plumbing of funding (the ancient, fixed and hidden pipework that dictates flow and direction and was built by people removed from current realities) has allowed capital to be redistributed in different ways to different groups”.

It has demonstrated how out of touch, unfit for purpose and power hungry the philanthropic world

He goes on to say that “this is one of the great and enduring benefits of The Social Change Nest. The shadow side is that The Social Change Nest highlights how much of an irredeemable failure the current system is. It has demonstrated how out of touch, unfit for purpose and power hungry the philanthropic world is that it has to find workarounds to its own processes.”

Despite all of the work we are doing to try to alleviate the risk for funders and to bridge the disconnect in more specific ways, it is also important to remember that this is a temporary solution to an issue that is dynamic and what should be considered as part of examining how power and controls flows through ‘resource’ (money, time people) management. This is why creating spaces such as Risky Business are so important and highlights the ever-crucial need to continue to learn together.

*who responded to the survey

Becca Bolton,

Project Manager at The Social Change Nest

If you’re interested in learning more about getting funding to grassroots groups, email us at hello@thesocialchangenest.org.

At The Social Change Nest, we’re radically transforming the funding landscape. We nurture grassroots groups and enable funders to support frontline social action.

As a community interest company (CIC), we’re the non-profit sister to The Social Change Agency.

In 2022 we were honoured to have The Social Change Nest listed among the Top 100 Social Enterprises in the UK.

Our vision is to build a vibrant and thriving civil society where social change happens from the ground up and the power to create change is open to all.

originally published at The Social Change Agency

featured photo by Sammie Chaffin on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

The Art of Collaborative Facilitation

“An effective facilitator is often what makes the difference between success and failure,” write Paul W. Mattessich and Kirsten M. Johnson, authors of Collaboration: What Makes It Work. “Facilitation isn’t magic, but it is multifaceted, challenging, and essential.”

If design is the framework or skeleton of a meeting, facilitation is what brings it to life. The work of a facilitator is to sense and respond to the needs of the group, while simultaneously guiding the network toward meaningful shared outcomes.

The crux of good facilitation, according to Adam Kahane, author of Facilitating Breakthrough, is not to get people to work together, but to remove the obstacles to connection and collaboration—obstacles like disconnection, debilitating conflict, and other forms of “stuckness.”13 After all, the Latin translation of the word facilitate is “to make easier.”

Picture a river: while you can’t push a river to move in a certain direction, you can remove rocks and logs impeding its path to allow the water to flow by itself. Good facilitators do not force things forward; they hold space for all points of view to be acknowledged while helping the conversation to flow.

Facilitating in collaborative contexts has a lot in common with good facilitation in any setting. As with any facilitation, it’s important to set the context for the gathering, ask good questions, and invite divergent perspectives. Facilitators also need to be able to acknowledge and disrupt harmful power dynamics to ensure that people have maximum agency to contribute.

In addition to these fundamentals, facilitating in a collaborative environment calls for operating with a network mindset. This means trusting the group rather than trying to control it, embracing emergence, inspiring self-organization, and naming dynamic tensions as they arise. It means embodying the norms they wish to see in the group. In many ways, the group will mirror the energy of the facilitator.

Facilitators are also tasked with demonstrating a comfort with ambiguity, with not knowing. The job of a facilitator is not to have all the answers. Instead, it is to ask good questions and help participants navigate the inherent complexities of life.

Drawing from experiences facilitating countless meetings with colleagues over the past ten years, we see the following as fundamental practices of good facilitation:

- Show up with your whole self

- Frame the context

- Hold space

- Invite divergence

- Stay emergent with intention

- Lead with humility

Show Up with Your Whole Self

As a facilitator, you have a specific job to do. But you’re also a complex, multifaceted human being. Bring the many sides of yourself to each convening as a way to model wholeness for the group. You do not need to be perfect. You will make mistakes, just like everyone else. Use humor and laughter to break moments of ten- sion and acknowledge shared imperfections and humanity.

Reveal emotion. Be open. Show the soul behind the role. It can make all the difference in the world. As you invite people to share why they have decided to participate, don’t be afraid to reveal why the work matters to you, as well.

Frame the Context

Imagine the very beginning of a convening. Everyone is gathered together, some for the first time. There you stand, ready to begin the session. What are the first words you will say? Think carefully, as they are vitally important. While it may be tempting to jump into the work of the day and blow by the opening, don’t miss this powerful moment. The opening to a convening is not a mere formality. “When we optimally prepare people for the form, function, and purpose of our gathering, they will be present in a way that greatly improves the chances of our purpose being actualized,” write Craig Neal and Patricia Neal in The Art of Convening.

Though the opening is a particularly significant moment, it’s also necessary to frame the context throughout the convening, including whenever you launch groups into a new activity or dis- cussion, as well as at the end of each day. Think of framing as the essential practice of clarifying the state of the moment and preparing the group for the work ahead. The best frames integrate what you heard from participants and contextualize the purpose of the convening or a particular session in a way that will increase engagement in the activities that follow.

Hold Space

There will inevitably be moments in convenings when the temperature in the room starts to rise. These are times when the conversation gets tense, people feel on edge, and nobody wants to openly acknowledge it. At this moment, many people will be tempted to retreat into what Robert Solomon and Fernando Flores call “cordial hypocrisy”—nice, polite conversations where real issues are swept under the rug.

The facilitator’s role here is to acknowledge what’s happening, invite people to take a breath, and then hold space so that the real issues can be worked through. Acknowledging what is happening can take the sting out of it, reducing the anxiety that the discomfort brings. Reminding people to stay present in the conversation may help them avoid falling into a stress response of “fight, flight, or freeze.” These are the moments of truth, the times when groups can either fall back into what’s comfortable or sit in the tension long enough to acknowledge unspoken realities and address critical issues.

Invite Divergence

Collaborative facilitators invite divergent perspectives, rather than avoid them. This is what enables participants to think creatively together, even when they disagree. When addressing an important issue, people may make statements so emotionally charged that they risk being isolated or labeled by others. At that moment, facilitators may feel the urge to move past the dissenting input and get back to the task at hand. What happens next can change the course of the group’s collective culture.

As a facilitator, instead of avoiding the disruption, turn to that person with your full attention and ask them to elaborate. Then, check to see if others feel similarly. If nobody does, you still need to validate that person’s perspective. It doesn’t matter if you agree or disagree with their opinion; what matters is making the room a safe place for different perspectives to be shared and honored. I learned this practice from Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff, creators of the Future Search process, and it’s served us more than a few times. By validating that person’s perspective, you make them feel heard, which allows the person to relax and rejoin the flow of the conversation.

Then, consider inviting people to share their own perspectives. This opens the space for people to offer contrasting opinions in a way that is respectful. These moments can dramatically shift the way in which participants interact with one another by creating a sense of psychological safety and appreciation for diverse points of view.

If you become stuck when something is going on in the room and you’re not sure what to do, put your faith in small groups or pairs. Quickly break the participants into groups of two to four, and ask them to discuss what’s happening in the room and what they think needs to happen next. Reflections can then be shared in the full group, which may give you a clue as to how to proceed (this might be a great time for a break as you quickly redesign the agenda!). This is one of Peter Block’s favorite tactics. “In doing this,” he writes, “we ask the community to take responsibility for the success of this gathering and express faith in their goodwill, even if they are frustrated with what is happening. . . . Doing this is an acknowledgment that critical wisdom resides in the community.”

Stay Emergent with Intention

No agenda is likely to survive contact with reality. As a facilitator, you have to be ready to adapt on your feet, sensing into where the energy is and what needs to happen next. At the same time, your facilitation shouldn’t be so loose that conversations are scattered. It’s a delicate balance of being open to emergence while being deliberate about closing conversations to move things forward.

In Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, Sam Kaner points out that groups in conversation typically need to move through a process of generating divergent and creative ideas before converging and arriving at a decision point. As facilitators, we give groups the space to sense their way through these conversations and the autonomy to shift from one conversation to the next. But before moving on to a new topic, we check to see if the first conversation can be closed with clarity—which may simply be a next step. If a conversation cannot be closed, we have the group acknowledge that they are purposefully shifting the focus of the discussion.

Lead with Humility

The role of the facilitator has inherent power. Facilitators usually have the final say over the agenda, they orchestrate the flow of the conversation, and they can influence who speaks and when. The act of facilitating is an act of exercising power. Facilitators use that power thoughtfully to make the gathering as welcoming, equitable, and open to shared leadership as possible.

As a facilitator, first examine your own privilege and implicit biases and acknowledge the power that comes with the role. Then, invite participants to provide candid feedback if they recognize opportunities to make the space more inclusive. If you come from a dominant cultural group, it is especially important to consider other cultural frames in the meeting design phase as well as in real time during a convening. Otherwise, you run the risk of unconsciously reinforcing dominant group norms that can alienate or even cause harm to some members of the group. When facilitators are too passive, they fail to fulfill some of the critical responsibilities of the role. “Far from purging a gathering of power,” passivity creates a power vacuum that others can fill “in a manner inconsistent with your gathering’s purpose,” writes Priya Parker.

Instead, I recommend practicing what Parker calls “generous authority”: lead the meeting confidently but also with humility, owning the power you’ve been entrusted with while using that power in service to others and to the group as a whole. Rather than using power over others to shut people down or control the conversation, emphasize power with, among, and within, to increase shared leadership across the group and guide the meeting toward life-affirming outcomes.

This piece is dedicated to David Sawyer, one of the best facilitators I’ve ever known.

David Ehrlichman is author of Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic Change (impactnetworks.xyz). He is currently working as cofounder and ecosystem lead of Hats Protocol (bit.ly/structurewithoutcapture), working to unlock a new paradigm of human coordination. From 2013-2023 David was cofounder and coordinator of Converge (converge.net), a network of practitioners who build and support impact networks.

David has helped form dozens of impact networks in a variety of fields, and was a founding coordinator for networks in the fields of environmental stewardship, economic mobility, access to science, civic revitalization, and web3. He speaks and writes frequently on networks and the future of coordination, finds serenity in music, and is completely mesmerized by his 1.5-year old daughter. Find his podcasts, writings, and other projects at davidehrlichman.com.

featured photo by kazuend on Unsplash

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

The Dots From Your Heart And Hand: Breathing Through Art

Like the fast-moving cars in cities, the fast-thinking minds of children throw smiles to my lips.

Building cars are complex – it takes a lot of creativity and expertise. On the flip side, kids crush complexities and build simple car toys that move – yet it takes their creative hands and expert minds to create.

So, what does it take to create the space for anyone anywhere to have the freedom to sparkle through their skills, gifts, stories and talents? Curiosity! The desire to see, think, hug, dance and work differently.

In the last 10 years, thinking about my network weaving journey – from dining with grassroots communities in African countries to virtually shaking hands with changemakers from 5 other continents of the world – one thing stands out: Humans are dynamic, gifts are uncountable, stories are limitless and creativity is endless.

I have seen the bright giggle, the reflective laughter, the inspiring aroma and spontaneous creations that people make in seconds, minutes and hours through their skills, stories and connecting with others.

Is that possible in an online space? You bet. Every word weaves into sentences, every silence makes sounds meaningful, every hello creates new possibilities.

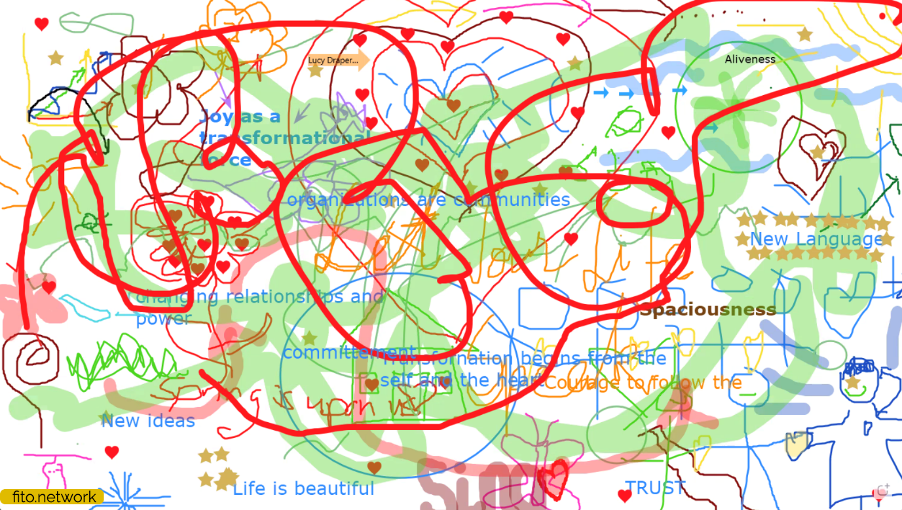

Here’s an example. Sometime in April 2023 I facilitated a session about transformation with June Holley and Brendon Johnson, where we had over 30 people, mostly meeting each other for the first time, come together to use the zoom whiteboard to bring back their childhood painting power.

Everyone had just come back from a breakout room where they shared their personal or professional stories of transformation with 2 or 3 other people.

I gave an easy question: “what does transformation mean to you?” and turned on some gentle background music.

Participant could only reply by drawing, painting, colouring, building or breaking. Here’s the result, after 5 mins:

How did they do this in 5 minutes, turning an empty, plain canvas on Zoom to an amazing painting that reflects how we feel about transformation? I caught some words there: ‘Joy, spaciousness, courage, trust, new, aliveness’

It was a messy and intriguing experience that left everyone feeling inspired.

The whiteboard canvas became a piece of art – coming from the dots in people’s hearts, that ran to their hands and it popped as a beautiful design. Art accommodates all of us, despite being from different disciplines, communities, and networks.

This creation led us into many other conversations -- building relationships, exploring systems change, social innovation, complexity, indigenous practices, exchanging ideas, and learning from one another.

Read some of the reflection of participants:

Lucy Draper-Clarke: “It looks to me like the real, the humanizing qualities like joy, there was commitment, the heart and beauty, using those as the energy for transformation. So rather than focusing so much on what needs to be transformed where the problems are, it's like channeling the best of human qualities. into the process. So that's what came up for me through the stories and through all the hearts on the screen.”

Andy Stoll: “Well, it's messy. I think that's when you think about transformation. It's not a linear, easy one, two, three, four. Lots of different hands create a very emergent property of. No one had a plan for our picture, but here we are.

In communities, families, networks and life, there are several dots, in different forms, shapes, sizes, colors, contexts, carrying different potentials.

There are many tiny dots of sand supporting the ocean floor. The gentle kiss of the sand is part of the fun at the beach, in that same way, the small talk to build trust may lead to building a network edifice.

Everyone in a network has a need and we bring the gifts of our heart and hands to paint each other’s life with meaning.

For example, there are several dots of scrap metal that make a gigantic car. Beyond the money that engineers make, they put their hearts and hands to creating magic that helps us travel millions of miles.

Just as important, the dot of a smile can inspire a hopeless heart and that smile can cause a catalytic and daring embrace to a weak soul.

It was a dot – a curious step you took – to read this blog, but it may just lead to truckloads of ideas and opportunities.

There are multiple dots of virtues lined up limitlessly in your genes – what will you turn them into?

In the last 10 years, Damilola Fasoranti’s work has helped communities and networks turn their education, gifts, and skills into desired solutions. As a catalyst coach, network weaver, and social entrepreneur, he loves co-creating ‘chaos’ in learning, sharing, and communities to accelerate them towards creating positive impacts. In 2017, he created the first grassroots makerspace - a school without teachers - to trigger creativity and innovation in grassroots communities, as the Chief Listener at Prikkle Academy, Nigeria.

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

Moving from ladders of engagement to self-organizing as decentralized leadership

Thanks to June Holley for thought partnership!

In campaign-based organizing, we tend to think of engaging people hierarchically: the goal is to move people up the ladder, progressively increasing their levels of engagement. Transplanting this to network organizing can give people a sense of “the network does all the things for network members,” where a few network facilitators become responsible for creating all engagement activities.

These practices shouldn’t be applied to networks. Why? Network members often experience shifts in capacity to engage in a way that is non-hierarchical. Because network participation often happens outside of the context of a job: we may devote less time to it – more sporadically and perhaps with varying levels of commitment. Network organizers should embrace these factors as part of how networks work, rather than trying to mash organizational thinking into network structures.

So, I’m starting to understand the idea of self-organizing as a decentralized, non-hierarchical version of engagement and leadership. We need to unlock this decentralization and move away from centralized levels of engagement. I say unlock because I think this involves a process of unlearning: doing things differently and practicing new ways of being with each other.

Attributes of a network that support self-organizing

- Widespread desire and openness to collaborate: it feels easy to meet people who are interested in talking, sharing learning, open to new ideas

- Self-authorization: you don’t feel like you have to ask for permission

- Accessible resources: including funds, spaces for discussion, knowledge databases, mentors or coaches, whatever else

- Liberatory culture: all network members actively practice undoing oppressions; working across privileges

- Spaces to learn in: you can see what others are doing, you feel like you can ask questions and get answers; you can see what others are learning

- Culture of seeing “failures” as rich learning opportunities: plus a shift away from an attitude of seeing these projects as a waste of time/resources

- Understanding: how individual’s efforts connect to network goals/values/principles

- Connecting the dots: ease of finding the right people to collaborate with and learn from

What prevents network members from self-organizing?

- Not feeling autonomy: having experienced generations of marginalization, disinvestment, and maybe never having seen someone like them in positions of power

- A narrow definition of leadership: privileging only a very specific type of person and way of interacting to be able to arrive to a position of power. This relationship to leadership trains us to do what we’re told rather than to initiate

- Resource dams and gatekeeping: only certain people have easy access to resources and/or resources are accessible but only after jumping through flaming hoops

- Lacking a sense of belonging to the network: why should I contribute? What’s in it for me?

- Culture: how we understand all of these things (autonomy, leadership, resources) is artificially narrow – we’ve become trained to understand them in certain ways and may have difficulty imagining that they could be different

How do we unlock decentralized engagement?

- Popular education: training and capacity building for and from within marginalized groups (these can be groups that are literally on the margins of a network, and/or groups of people that have been pushed to the margins of dominant society)

- Less gatekeeping of funds: innovation funds and shared gifting can be a way for funders and other gatekeepers to begin to practice letting go of control. Decolonial commons and cooperatives are closer to real, community control of resources. (Consider also: reparations!)

- Communities of practice: to unlearn some ways of being and practice new ones – creating new cultures of interacting: specifically anti-racist, feminist, decolonial, and otherwise undoing hierarchies. Pair that with being caring and holding space for change and cultural shifts.

- Protocols and practices: break down how to do things – the steps to take to form a project – as an activity that regularly happens in a network

- Naming power: measuring and creating intentional interventions around demographic shifts for who is/remains are in positions of power in a network will help xyz

- Logging Data: collecting, sharing, and visualizing data that gives us a real-time picture of where we are in this shift

Finding best fit: using network weaving to help people find the “right” person/people to start a project with

About Ari Sahagún

I grew up in the tallgrass prairies of Illinois, where the lanky sandhill cranes pause on their way to and from Mexico. Retracing one of my family’s roots, I’ve recently moved south to Mexico City to do what I do as a mixed heritage person: build bridges. One facet of my work is building bridges between extractive capitalism/colonialism and a society that repairs and regenerates from these traumas. I’ve run praxis groups on decolonization and helped investors move hundreds of thousands of dollars to Black- and indigenous-led projects in the US and internationally. The other part of my work is building bridges that support movement networks on the path toward a more just society. Right now, this looks like facilitating peer learning among climate justice organizations in the United States, mapping interconnections that support power-building in California, and co-designing a complex, emerging network to support health equity. My specialties are at the intersections of justice, co-design, network strategy, social network analysis, technology, and communication cultures.

featured image found HERE

Network Weaver is dedicated to offering free content to all – in support of equity, justice and transformation for all.

We appreciate your support!

Understanding network strategy

Every organization needs an effective strategy. Strategy can refer to an overarching strategic plan at the organizational level or a strategy towards achieving specific organizational needs and goals. A strategy will set the way forward for an organization in alignment with its overarching vision and mission. It will articulate the priorities and directions the organization should take as well as convey the “what”, “why”, and “how” to accomplish its goals, often within a given period, by clearly defining the pathways towards achieving them.

At Collective Mind, we’ve learned a number of lessons through our work with networks developing strategies and strategic plans.

Context matters

Strategy for networks is different than strategy for more traditional organizational models. Networks are a unique type of organization with a complex operating model. They are different in how they’re organized, who’s involved, and how they get things done.

First, networks are horizontal, flat structures: they are not top-down, hierarchical, or directive. They are loosely controlled, with multiple mechanisms for collaboration and without any mechanisms for command and control.

Second, networks are comprised of members — without members, you don’t have a network — and the complexity of that membership typically matches the complexity of the network’s issue area. As such, the network must meaningfully integrate a wide diversity of people and/or organizations in an equitable fashion. It must be flexible and agile enough to capture the emergence that arises from such diversity and the interconnections across it.

Finally, because of these characteristics, networks operate differently. They seek to harness the collective intelligence within them, dispersing leadership and sharing decision-making. They typically don’t procure deliverables but focus on stimulating activities by their members, who are responsible for creating the outputs of the network. This relationship between members and the network is typically voluntary and about creating shared value, not premised on a contractual relationship. Consequently, the network’s staff (if there is a staff) aims to support its members by helping facilitate the production of outputs, rather than directly implementing and delivering those themselves.

How networks are different influences strategy

Within this unique and complex operating environment of networks, we can consider strategy differently in at least three ways: process, content, and implementation.

Process: we must ensure that the process to develop the strategy or strategic plan empowers members and any other stakeholders and establishes their ownership of it. This requires a participatory, inclusive process with mixed methods for inclusive, meaningful participation. An iterative and adaptive process should build from one step to the next toward the final strategy. The steps of the process should ensure ongoing triangulation and validation of key ideas, needs, priorities, and pathways with stakeholders as they are developed.

Content: we must ensure that the strategy or strategic plan represents a collective effort. It should set collective priorities and determine the collaborative paths to achieve them by facilitating consensus-building throughout the process. The plan’s priorities and goals should be grounded in the needs, interests, and capacities of the membership. The substance of the plan must reflect the goals, expectations, and motivations of the members.

Implementation: we must clarify and define who will implement the strategy. As explained above, in the context of a network, it must be its members that produce the outputs with support from the network staff. We must clarify how this can be done realistically and right-size the strategy to ensure the feasibility of that implementation (for example, recognizing the limitations on members’ capacity, time, etc.). We must ensure that the plan supports the network to align energy, resources, and stakeholders for collective impact.

A clear and effective strategy will define in what direction the network and its membership will move forward. It will reflect and align with the needs and interests of its members, defining initiatives and activities through which members can participate and collaborate. Consequently, it will clearly articulate the unique added value that the network as a collective can create that is greater than the sum of those parts.

Interested to hear more about how we approach strategy development with networks and how we can support you? Contact Kerstin Tebbe at kerstin@collectivemindglobal.org.

Kerstin Tebbe has almost 20 years of experience supporting networks and multi-stakeholder collaboration. Her passion for networks was ignited by 6.5 years (2008-2014) spent on the Secretariat for the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) where she coordinated an international technical working group, established a pan-African knowledge hub, and served as Deputy/Acting Director of the network. As a consultant from 2014 to 2019, Kerstin supported networks and multi-stakeholder initiatives around the world with strategy design, program review, knowledge management, capacity building, and facilitation. Kerstin founded Collective Mind in late 2019 after many years of independent study and research on networks. With Collective Mind, she has supported networks from local to global on a wide range of challenges. Kerstin has lived and worked in New York, Buenos Aires, Paris, Nairobi, Geneva, and Washington DC. When she’s not thinking about networks, she’s dancing.

originally published at Collective Mind